CHAPTER 12

POPULATION HEALTH

A 2017 documentary titled A Coalition of the Willing describes a population health team in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, that has focused on the elderly since 2001 (Falk 2017). Health Quality Partners, made up of data analysts, social workers, nurses, and doctors, uses data to find extreme patterns of health needs in a population—a practice known as “hotspotting”—to identify those with the most need. They pull data from a vast database every night to identify areas of the community that are in need and then move into the area to care for the people there. Through this process the team has helped reduce mortality in this population by 25 percent. A testimonial on the group’s website (www.hqp.org) reported, “At the time of starting the program, I was within 2–3 weeks of having a stroke because of my blood pressure. The care I received probably saved my life.”

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you will be able to

Define population health.

Define population health.

Differentiate between population health and public health.

Differentiate between population health and public health.

Evaluate the significance of determinants of health.

Evaluate the significance of determinants of health.

Comprehend health disparities among individuals and groups.

Comprehend health disparities among individuals and groups.

Understand “big data” in healthcare and the challenges associated with its use.

Understand “big data” in healthcare and the challenges associated with its use.

Compare population health management tools and models.

Compare population health management tools and models.

Analyze the role of healthcare in population health management.

Analyze the role of healthcare in population health management.

WHAT IS POPULATION HEALTH?

The term population health was first used in a report published in Canada in the early 1990s, although no precise definition was given (Evans, Barer, and Marmor 1994). Nearly a decade later, researchers David Kindig and Greg Stoddart (2003) defined population health as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.” According to these authors, population health looks at the link between health outcomes, health determinants, and health policies and interventions. Likewise, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) views population health as a partnership among public health agencies, industry, academia, healthcare, and local government entities to achieve positive health outcomes (CDC 2019c). In 1998, Health Canada, that country’s agency responsible for public health policy, defined the overall goal of population health: to improve the health of the entire population and to reduce inequalities among population groups.

Population health differs from public health. Public health is concerned with protecting and improving the health of people and communities. The American Public Health Association teaches that public health agencies conduct research, gather evidence, track disease outbreaks, prevent injury and illness, set standards to protect workers, and influence school nutrition, among other functions (APHA 2020). The CDC promotes three core functions of public health: assessment, policy development, and assurance. These three functions encompass ten essential environmental public health services: monitoring health, diagnosing and investigating health problems, educating and empowering people, mobilizing community partnerships, developing health policies, enforcing laws related to health and safety, linking people to health services, ensuring a competent environmental health workforce, evaluating population health services, and researching innovative solutions to health problems (CDC 2019b) (exhibit 12.1).

EXHIBIT 12.1 Ten Essential Environmental Public Health Services

Details

The three core functions of public health are: assessment, public development, and assurance. The three functions encompass the following ten essential environments. The details are as follows:

- Monitor health

- Diagnose and investigate

- Inform, educate, empower

- Mobilize community partnerships

- Develop policies

- Enforce laws

- Link to services

- Assure competent workforce

- Evaluate

- Research.

Source: PHIL (2017).

While public health experts play a vital role in the health of US states and communities, they partner with healthcare providers, community health workers, government agencies, schools, nonprofit agencies, researchers, business, community leaders, and others in the task of population health.

DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Determinants of health are factors that are drivers of health outcomes, and they are key to understanding the health of populations. Determinants of health are divided into five categories (Evans and Stoddart 1990). These include medical care, individual behavior, social environment, physical environment, and genetics. Medical care includes prevention, screening, treatment, and management of disease. Individual behaviors are lifestyle decisions that may include smoking, diet, and exercise. Social environment focuses on socioeconomic factors such as income, education, and occupation. Physical environment comprises clean air and water, opportunities to recreate, and even buildings in a community. Genetics are the characteristics that people inherited from their ancestors and their contribution to health outcomes (Kindig, Asada, and Booske 2008).

Social and physical environment together are commonly referred to as social determinants of health (CDC 2018). The Kaiser Family Foundation defines social determinants of health as encompassing economic stability, neighborhood and physical environment, education, food, community and social context, and the healthcare system. All of these factors affect the health outcomes of mortality, morbidity, life expectancy, healthcare expenditures, health status, and functional limitations (Artiga and Hinton 2018).

Studies have demonstrated that social determinants have a significant impact on health. For example, research has documented children’s exposure to lead as a result of poor housing (Ahrens et al. 2016); the connection between food insecurity and kidney disease (Banerjee et al. 2017); disparities in the prevalence of diabetes (Beckles and Chou 2016); economic insecurity and its relationship to partner and sexual violence (Breiding et al. 2017); avoidable deaths from cardiovascular disease (Greer et al. 2016); and the relationship between socioeconomic status and cigarette smoking (Helms, King, and Ashley 2017).

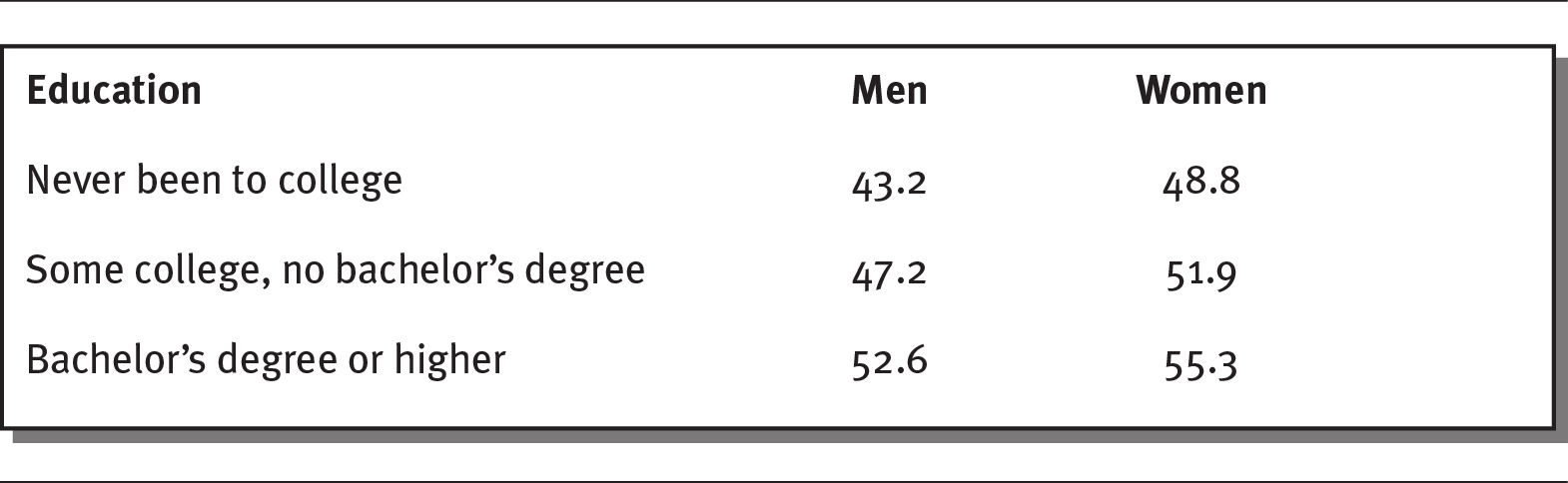

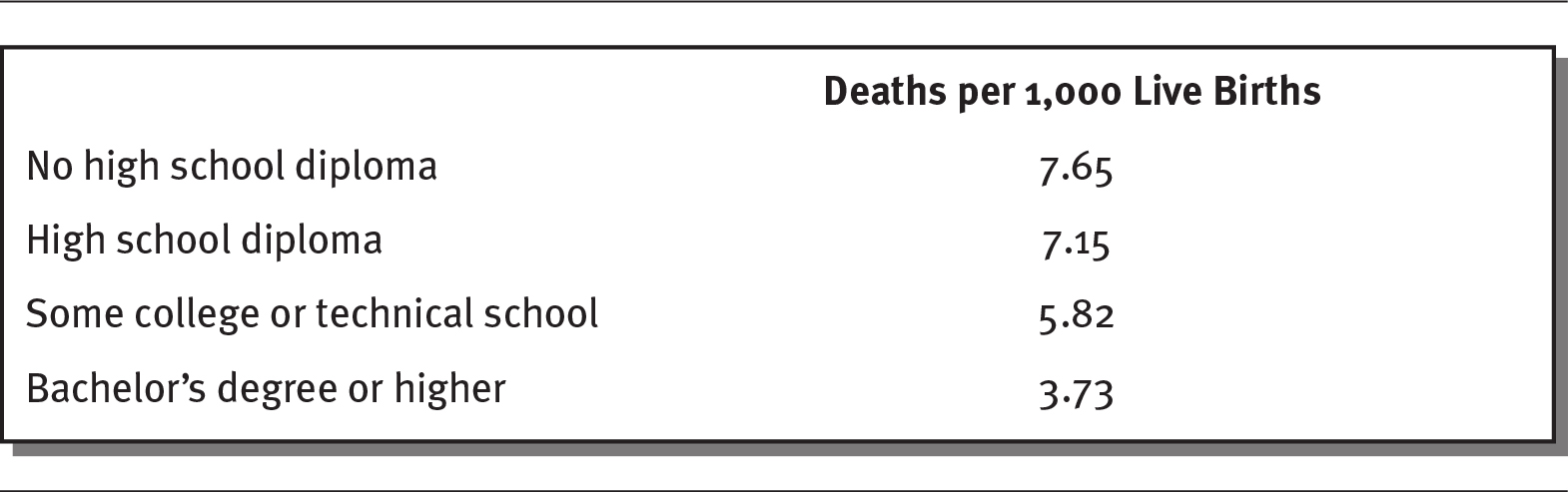

Evidence gathered over the past 25 years has shed light on the significance of socioeconomic factors such as income, wealth, and education as causes of a variety of health problems (Braveman and Gottlieb 2014). Exhibits 12.2, 12.3, and 12.4 illustrate three examples of the impact of social determinants on health.

EXHIBIT 12.2 Years of Life Remaining at Age 30 by Education, 2010

Details

The details of education, for men and for women respectively are as follows:

- Never been to college: 43.2, 48.8.

- Some college, no bachelor's degree: 47.2, 51.9.

- Bachelor’s degree or higher: 52.6, 55.3.

Source: Luy et al. (2019).

EXHIBIT 12.3 Infant Mortality Rates by Education, 2009

Details

The details of death per 1000 live births are as follows:

- No high school diploma: 7.65

- High school diploma: 7.15

- Some college or technical school: 5.82

- Bachelor’s degree or higher: 3.73.

Source: Mathews and MacDorman (2013).

EXHIBIT 12.4 Overall Health Status by Income, 2018

Details

The details are as follows:

- Of those who make less than $35,000 per year, 54% report very good to excellent health and 18% report poor to fair health.

- Of those who make more than $100,000 per year, 79% report very good to excellent health and 4% report poor to fair health.

Source: NCHS (2018).

Some researchers have attempted to identify the determinants of mortality. They suggest that 40 percent of deaths are caused by behavioral factors, 30 percent by genetics, 15 percent by social circumstances, 10 percent by medical care, and 5 percent by physical environmental exposures (McGinnis, Williams-Russo, and Knickman 2002).

The determinants of health have significant and complex interactions with each other and with the outcomes themselves. Some outcomes have a reverse causality on determinants; for example, a lack of income may be a barrier to attaining higher education, eating a good diet, and living in an environment that allows for physical activity.

HEALTH DISPARITIES

The World Health Organization (WHO) uses fairness as a way to compare health systems around the world. The WHO (2000) argues that “it is not sufficient to protect or improve the average health of the population, if—at the same time—inequality worsens or remains high because the gain accrues disproportionately to those already enjoying better health.” Good health, according to the WHO, represents the “best attainable average level” and the “smallest feasible differences among individuals and groups.” Health disparities are preventable differences among population groups in the burden of disease or injury. Health disparities may also refer to differences among groups in terms of health insurance coverage, access to healthcare, or quality of healthcare. Health disparities occur when one population group is not afforded equal or fair treatment or the burden of disease or injury falls disproportionately on certain populations.

Data clearly identify health disparities in the areas of race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, age, location, gender, disability status, and sexual orientation (Orgera and Artiga 2018). A CDC report went further, reviewing disparities in 29 areas within six broad categories: social determinants of health, environmental hazards, healthcare access and preventive services, behavioral risk factors, morbidity, and mortality. The CDC report was designed to assist public health, academia, and clinical experts; policymakers; community leaders (including healthcare leaders); researchers; and the general public in overcoming disparities (CDC 2013).

Health disparities affect the healthcare industry and US population as a whole, limiting the quality of care for all and imposing a huge financial burden on the entire population. A 2018 analysis estimated that health disparities resulted in $93 billion in excess medical care costs and $42 billion in lost productivity per year. The US economy also suffers as a result of premature deaths (Turner 2018).

RACE/ETHNICITY

People of color generally experience more barriers to accessing healthcare and use less healthcare than white Americans. According to a Kaiser Family Foundation study, among nonelderly adults, Hispanics/Latinos, African Americans, and American Indians and Alaska Natives are more likely to go without care or delay care that they need. Whites tend to identify a personal primary care provider more often than Black or Hispanic/Latino adults (Orgera and Artiga 2018). Non-Hispanic/Latino Black adults are at least 50 percent more likely to die prematurely of heart disease or stroke than their non-Hispanic/Latino white counterparts. Adult diabetes is more prevalent in Hispanics/Latinos, non-Hispanic/Latino Blacks, and those of mixed race. The infant mortality rate is high for non-Hispanic/Latino Blacks—more than twice that of non-Hispanic/Latino white Americans (CDC 2013).

A 2017 report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality supports this finding, indicating that Blacks, American Indians and Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders experience worse access to healthcare compared with whites for 40 percent of the measures studied, such as access to care, patient safety, care coordination, effectiveness of care, and affordable care (AHRQ 2019).

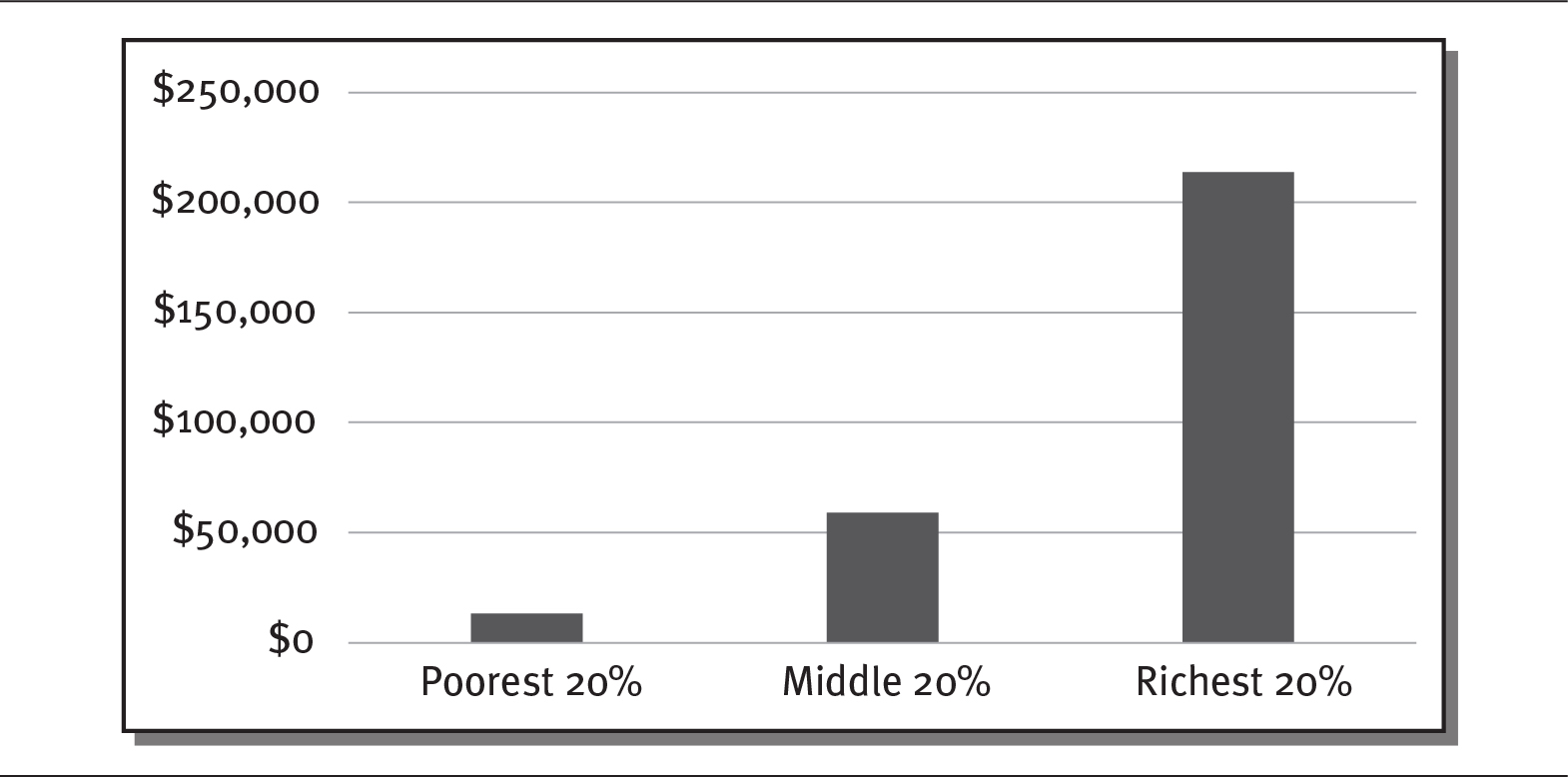

SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS

Wide gaps exist between the richest and poorest households in the United States. A 2016 JAMA study found a gap in life expectancy of about 15 years for men and 10 years for women when comparing the richest 1 percent of individuals with the poorest 1 percent (Chetty, Stepner, and Abraham 2016). Exhibit 12.5 illustrates the income gaps between the nation’s richest households, with an average income of $214,000 in 2016, and the poorest, which averaged only $13,000 (Semega, Fontenot, and Kollar 2017).

EXHIBIT 12.5 The Income Gap in the United States, 2016

Details

The x-axis shows segments of population and the y-axis shows dollars from 0 to 250000 dollars in increments of 50000. The details are as follows:

- Poorest 20 percent: 10000 dollars.

- Middle 20 percent: 55000 dollars.

- Richest 20 percent: 220000 dollars.

Source: Semega, Fontenot, and Kollar (2017).

Americans living at or below the federal poverty level experienced worse access to care compared with higher-income people (incomes of 400 percent of the federal poverty level and higher) for all access measures except having a usual source of care with evening and weekend office hours. Even with this source of care, among low-income adults, visits to emergency departments in 2016 for asthma increased from 809 to 923 per 100,000 population, while the number of higher-income adults visiting the emergency department for the same reason decreased from 348 to 310 per 100,000 population. Significant disparities persist for low-income Americans who reported that they were unable to get the care they needed for financial reasons (AHRQ 2017).

GENDER AND SEXUAL ORIENTATION

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) reports that women are twice as likely as men to experience depression and more likely to admit to negative mood states. Women also have a harder time quitting smoking. Nicotine replacement therapies such as patches and gum work better in men than in women, an effect that may be related to women’s metabolism. Women are more susceptible to cardiovascular disease and experience osteoporosis more often. Finally, the NIH reports that sports injuries are more common in women and girls because of their knee and hip anatomy, imbalanced leg muscle strength, and looser tendons and ligaments (NIH 2019). A number of studies conducted by NIH offices and affiliates have placed women at higher risk of health problems related to alcohol use, breast and lung cancer, depression and other mental health disorders, and severe flu symptoms (NIH 2020). However, according to the CDC (2019a), men are about four times more likely to commit suicide than women, regardless of age or race/ethnicity.

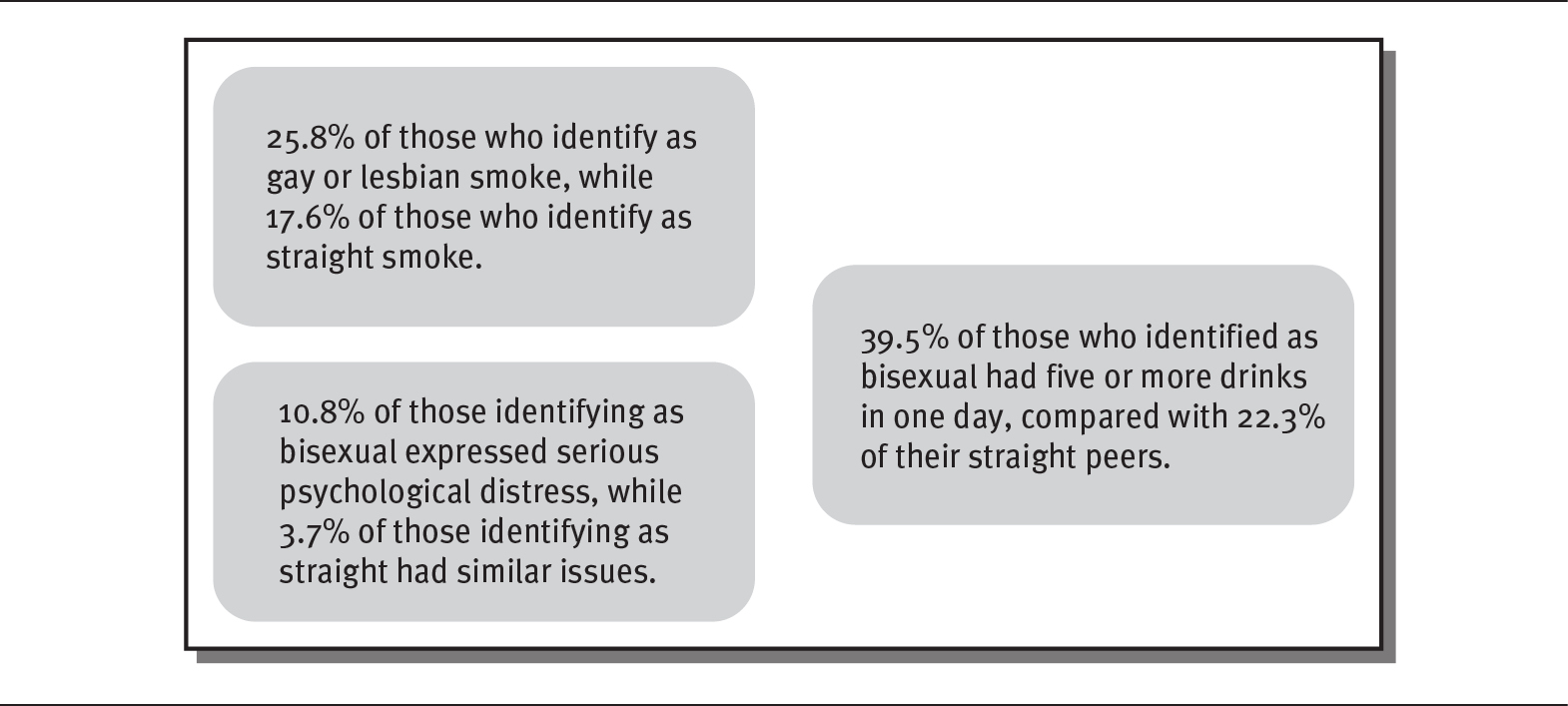

LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning) individuals, according to the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, report higher rates of health disparities linked to social stigma and discrimination. These include psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, and suicide (ODPHP 2020d). Many LGBTQ individuals delay care or receive inferior care because of real or perceived homophobia or discrimination by healthcare providers (GLMA 2006). The National Health Interview Survey of 2013 identified a number of health indicators for which LGBTQ individuals are at higher risk (see exhibit 12.6): cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, psychological distress, healthcare access (in defining a “usual place to go” for care), and failing to obtain needed medical care (Ward et al. 2014).

EXHIBIT 12.6 Selected Health-Related Behavior Indicators of US Adults, by Sexual Orientation and Gender, 2013

Details

The details are as follows:

- 25.8 percent of those who identify as gay or lesbian smoke, while 17.6 percent of those who identify as straight smoke.

- 39.5 percent of those who identified as bisexual had five or more drinks in one day, compared with 22.3 percent of their straight peers.

- 10.8 percent of those identifying as bisexual expressed serious psychological distress, while 3.7 percent of those identifying as straight had similar issues.

Source: Ward et al. (2014).

GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION

Where a person chooses to live profoundly affects their health outcomes. In 2014, many southern and southwestern states (Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas, and West Virginia), several western states (Nevada, Oregon, and Wyoming), and one midwestern state (Indiana) had the lowest overall quality scores (AHRQ 2017).

U.S. News & World Report and the Aetna Foundation assessed nearly 3,000 US counties across 81 metrics in ten categories. The analysis showed that substantial challenges among Black residents included homicide rates, low birth weight, and local access to food. The study found that nearly 700 communities had Black population segments larger than the national average, and only 30 of those communities were among the top 500 healthiest communities (McPhillips 2018).

POPULATION HEALTH MANAGEMENT

Gathering patient and community health data from a variety of sources, analyzing those data to create an understandable picture of the health of a population, and then taking action to improve the health of that group is population health management. A number of techniques and tools are used to create that picture. The tools covered here include community health needs assessments, County Health Rankings, the Healthy People initiative, Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships, the Association for Community Health Improvement’s Community Health Assessment Toolkit, the Community Tool Box, and the Guide and Template for Comprehensive Health Improvement Planning.

ANALYTICS AND POPULATION HEALTH

One study estimates that healthcare organizations had collected 150 exabytes—or 150 billion gigabytes—of data through 2011 (Terry 2013). Referred to as big data, these data take the form of electronic health records and financial billing systems. These data allow researchers to understand when an individual is likely to shift to a higher-risk category and allow a provider to intervene. The data sets provide the foundation for modeling patient populations by tracking the health risk status of a particular population (Bradley 2013).

Managing healthcare data poses a number of challenges. Finding employees with the skills to use the data can be difficult. Information technology investment in healthcare is among the lowest of all industries, even though the amount of data collected in healthcare exceeds that of manufacturing, financial services, or media. One study gave healthcare a score of 2.4 out of 5 in data management, use, and monetization—well below average according to some competency metrics (Kent 2018).

A 2019 study found that only one in five senior healthcare organizations use analytics for population health (Sucich 2019). The study, which surveyed 110 senior healthcare leaders, revealed the following:

90 percent are using data analytics in clinical areas.

90 percent are using data analytics in clinical areas.

Only about 22 percent are using analytics for population health.

Only about 22 percent are using analytics for population health.

Among healthcare organizations that are not using analytics, only about 32 percent say that population health is a top priority.

Among healthcare organizations that are not using analytics, only about 32 percent say that population health is a top priority.

Data-driven population health is an area of tremendous potential. Data exist in health and financial records, surveys, and public health records. However, the models for pulling data, and expert staff to analyze and use them, are not fully in place.

COMMUNITY HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires tax-exempt hospitals to complete a community health needs assessment (CHNA) every three years. This report is intended to assess the health needs of a community, prioritize those needs, and identify resources to address them. Under Internal Revenue Service rules, tax-exempt hospitals must solicit input from at least one state, local, tribal, or regional government public health department and members of medically underserved, low-income, and minority populations in the community. Hospitals must also consider written comments on their most recently conducted CHNA and outline how they plan to address the recommendations. These reports must be made available to the general public (IRS 2019). The sidebar presents an example of a CHNA partnership with Intermountain Healthcare, the Utah Department of Health, and several local health districts in that state.

Around the same time that the ACA was enacted, the Public Health Accreditation Board required a similar community health assessment of all local and state public health agencies that wished to be accredited (ASTHO 2017). The board’s accreditation standards require public health departments to take the following steps:

A CHNA PARTNERSHIP IN UTAH

A CHNA PARTNERSHIP IN UTAH

Intermountain Healthcare, based in Utah, joined forces with state and local public health departments, community leaders, and representatives of local underserved populations to complete a CHNA in 2013 and another in 2016. Intermountain Healthcare’s hospitals and local health departments, along with the Utah Department of Health, cohosted community input meetings. Participants included minority, low-income, and uninsured populations, as well as safety net clinic employees, school representatives, health advocates, mental health providers, local government leaders, and senior service providers.

In 2016, Intermountain worked with local health departments and the Utah Department of Health, along with some of Intermountain’s clinical and operational leadership, to identify 100 health indicators representing 16 broad health issues (IMC 2016). These indicators become the drivers of action by Intermountain Healthcare in communities around the state. Priority health needs included the prevention of prediabetes, high blood pressure, depression, and prescription opioid misuse. Results of the CHNA were used to develop a three-year implementation strategy for Intermountain. Each of Intermountain Healthcare’s 21 Utah hospitals developed its own CHNA report and implementation plan (see https://intermountainhealthcare.org/about/who-we-are/chna-reports). They have continued to monitor quarterly the outcome measures established in the CHNA.

The Utah Department of Health (2016) and each local health department established its own list of priorities, many of which were in line with those of Intermountain. The Utah Department of Health and the Weber-Morgan Health Department (2016) in northern Utah, for example, focused on preventing suicide, obesity, and adolescent substance abuse.

Be a part of or lead a collaborative process resulting in a community health assessment.

Be a part of or lead a collaborative process resulting in a community health assessment.

Collect and maintain reliable data on public health conditions of the population served.

Collect and maintain reliable data on public health conditions of the population served.

Analyze these data and report on trends in health issues, environmental public health hazards, and social and economic health factors.

Analyze these data and report on trends in health issues, environmental public health hazards, and social and economic health factors.

Develop recommendations regarding public health policy, programs, and interventions.

Develop recommendations regarding public health policy, programs, and interventions.

The benefits and outcomes of community health assessments include the following:

Improved organizational and community coordination and collaboration

Improved organizational and community coordination and collaboration

Stronger partnerships between healthcare and public health at the state and local levels

Stronger partnerships between healthcare and public health at the state and local levels

Data-driven baselines against which implementation can be measured

Data-driven baselines against which implementation can be measured

Identification of strengths and weaknesses related to improvement efforts

Identification of strengths and weaknesses related to improvement efforts

CHNAs are required of nonprofit hospitals and public health departments seeking accreditation. Many state and local health departments have chosen not to complete the accreditation process but are completing health assessments as part of their efforts to support the health of the populations they serve.

COUNTY HEALTH RANKINGS

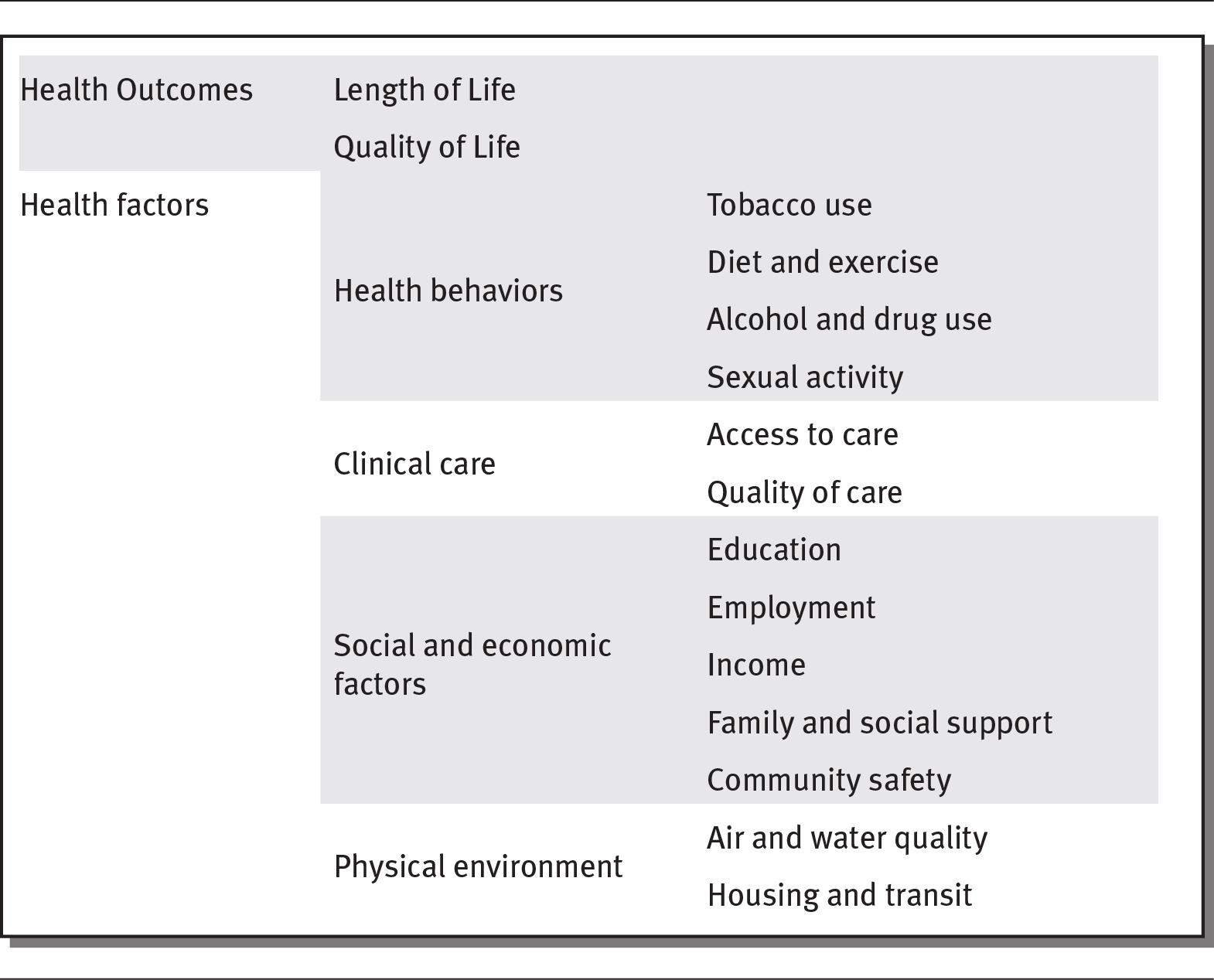

Annually since 2010, the University of Wisconsin’s Population Health Institute and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation have produced the County Health Rankings for the nation’s more than 3,000 counties. Data gathered from a number of US sources are analyzed and reported. The rankings take into account health factors such as health behaviors, clinical care, and social and economic factors; the physical environment; and health outcomes, measured by morbidity and mortality rates (Remington, Catlin, and Gennuso 2015). Exhibit 12.7 summarizes the County Health Rankings.

EXHIBIT 12.7 County Health Rankings Model

Details

The details are as follows:

- Health Outcomes: Length of Life, Quality of Life.

- Health factors: Health behaviors

- Tobacco use

- Diet and exercise

- Alcohol and drug use

- Sexual activity

- Clinical care:

- Access to care

- Quality of care

- Social and economic factors

- Education

- Employment

- Income

- Family and social support

- Community safety

- Physical environment

- Air and water quality

- Housing and transit.

Source: Remington, Catlin, and Gennuso (2015).

The County Health Rankings are widely used in the United States. The primary use of these and similar rankings is to help set goals and public health agendas. Local health departments can use them as part of their education efforts and to bring awareness to public health issues in a community. This can lead to motivation and debate over what needs to be done to help community populations. A second purpose is to establish responsibility for population health (Oliver 2010). However, some have criticized these rankings for what they view as the arbitrariness of the measures, the emphasis on insignificant differences, and the tendency to focus only on the data in the rankings (Arndt et al. 2013; Kanarek, Tasi, and Stanley 2011).

The 2019 County Health Rankings noted the following findings (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation 2019):

More than one in ten households across the United States spend more than half of their income on housing costs. Renters spend a substantially higher percentage of their income on housing compared with homeowners. This is especially true for low-income households.

More than one in ten households across the United States spend more than half of their income on housing costs. Renters spend a substantially higher percentage of their income on housing compared with homeowners. This is especially true for low-income households.

Across the counties, households described as “severely cost burdened” are associated with more food insecurity, child poverty, and fair or poor health status.

Across the counties, households described as “severely cost burdened” are associated with more food insecurity, child poverty, and fair or poor health status.

Black residents face greater barriers than white residents. Nearly one in four Black households spend more than half of their income on housing.

Black residents face greater barriers than white residents. Nearly one in four Black households spend more than half of their income on housing.

About 13 percent of those living in the top-performing (10 percent) counties rate themselves in poor health, while 15 percent of those living in the bottom-performing counties (10 percent) do.

About 13 percent of those living in the top-performing (10 percent) counties rate themselves in poor health, while 15 percent of those living in the bottom-performing counties (10 percent) do.

The difference between the top- and bottom-performing counties is more pronounced for child poverty, with 15 percent reported in the top-performing counties and 22 percent in the bottom-performing counties.

The difference between the top- and bottom-performing counties is more pronounced for child poverty, with 15 percent reported in the top-performing counties and 22 percent in the bottom-performing counties.

Across the counties, every 10 percent increase in the share of severely cost burdened households is linked to 29,000 more children in poverty, 86,000 more people who are food insecure, and 84,000 more people in fair or poor health.

Across the counties, every 10 percent increase in the share of severely cost burdened households is linked to 29,000 more children in poverty, 86,000 more people who are food insecure, and 84,000 more people in fair or poor health.

The County Health Rankings show clearly that where people live makes a difference in their health outcomes.

HEALTHY PEOPLE

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, an agency of the US Department of Health and Human Services, has spearheaded the development and implementation of the Healthy People initiative for four decades. Efforts are now underway for the introduction of Healthy People 2030 (ODPHP 2020c). The national health objectives set for the Healthy People 2020 initiative are based on evidence gathered before, during, and at the conclusion of the initiative. The overarching goals of Healthy People 2020 are as follows: (ODPHP 2020a):

Attain high-quality, longer lives free of preventable disease, disability, injury, and premature death.

Attain high-quality, longer lives free of preventable disease, disability, injury, and premature death.

Achieve health equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of all groups.

Achieve health equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of all groups.

Create social and physical environments that promote good health for all.

Create social and physical environments that promote good health for all.

Promote quality of life, health development, and healthy behaviors across all life stages.

Promote quality of life, health development, and healthy behaviors across all life stages.

Each Healthy People initiative establishes several topic areas and hundreds of objectives, supported by baseline national data and targets for improvement. In most cases, interventions and resources are offered to achieve the objectives. The sidebar features an example of how Healthy People 2020 made a difference in one Maryland community.

HIGH INCIDENCE OF END-STAGE RENAL DISEASE IN MARYLAND’S LATINO POPULATION

HIGH INCIDENCE OF END-STAGE RENAL DISEASE IN MARYLAND’S LATINO POPULATION

According to 2006–2010 data, the Maryland Department of Health learned that diabetic end-stage renal disease among Hispanics/Latinos was 10 percent to 20 percent higher than for non-Hispanic/Latino whites ages 55 and older. Related renal disease and obesity rates have increased over the last three decades. With funding from the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion through the Healthy People 2020 Community Innovations Project, the department hired a Hispanic/Latino community member to reach out to the neighborhood to organize health screenings and education (ODPHP 2013). Before the introduction of the program, only 24 of 128 participants reported having their cholesterol checked in the past two years. After participating in the project, all of the participants were screened. Nearly one-third learned that they had elevated cholesterol. All were taught about exercise and healthy eating. In addition, many participants were connected with a primary care provider.

OTHER POPULATION HEALTH MANAGEMENT MODELS AND TOOLS

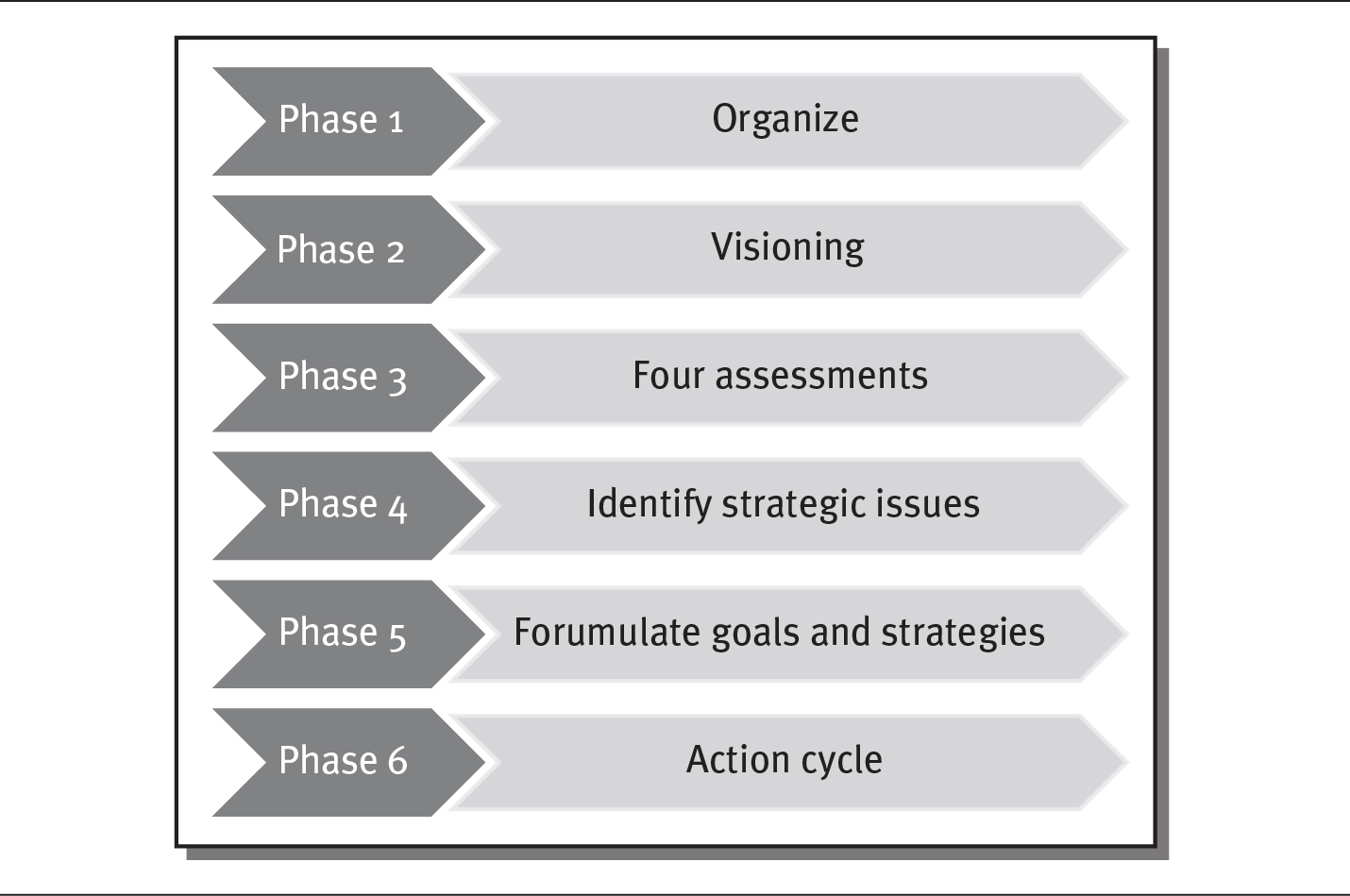

The CDC identifies common elements of assessment and planning frameworks and provides information about commonly used frameworks (CDC 2015). Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (MAPP) is a tool that was developed to help communities prioritize public health issues and identify resources to address them. It is sometimes used to develop community health assessments and improvement plans. MAPP is broken down into six phases, illustrated in exhibit 12.8.

EXHIBIT 12.8 Phases of Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (MAPP)

Details

The details of the phases are as follows:

- Phase 1: Organize

- Phase 2: Visioning

- Phase 3: Four assessments

- Phase 4: Identify strategic issues

- Phase 5: Formulate goals and strategies

- Phase 6: Action cycle.

Source: NACCHO (2020).

MAPP comprises four assessments: community themes and strengths, local public health system, community health status, and forces of change. MAPP focuses on the development of community partnerships and a continuous cycle of planning, implementation, and evaluation.

The Association for Community Health Improvement’s Community Health Assessment Toolkit includes nine steps of strategizing engaging stakeholders, defining the community, collecting and analyzing data, prioritizing community health issues, documenting results, planning, implementation, and evaluation. It is designed as a resource for hospitals and public health agencies to conduct community health assessments (ACHI 2017).

The Community Tool Box, created by the University of Kansas, provides information on building healthy communities. One chapter of the tool box focuses on the health assessment process. It includes many of the steps listed in the other models, broken down into 24 sections (University of Kansas 2018).

The Guide and Template for Comprehensive Health Improvement Planning was developed by the Connecticut Department of Public Health. The department created the four-part plan prior to the passage of the ACA to facilitate the development of CDC-sponsored prevention and control plans. The first part of the template outlines the planning process. The second part contains examples of vision, mission, goals, objectives, strategies, and work plans. The third part focuses on criteria for setting priorities and focus areas. The last part contains a template for the health improvement plan. It is based on historically successful planning initiatives (Bower 2009).

The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials also created a booklet called Developing a State Health Improvement Plan: Guidance and Resources: A Companion Document to ASTHO’s State Health Assessment Guidance and Resources. The ideas and principles in this guide are similar to those in the other resources discussed here. This 100-page booklet focuses on engaging stakeholders, creating a vision, gathering and leveraging data, establishing and communicating priorities, developing objectives and measures, and implementing and evaluating the state health improvement plan (ASTHO 2019).

HEALTHCARE’S ROLE IN POPULATION HEALTH

The Healthy People 2010 and 2020 initiatives included objectives specific to population health and health professions education. For example, several objectives promoted the inclusion of core disease prevention and population health content for students who will eventually care for patients (ODPHP 2020b). This emphasis applies to individual patients and clients cared for by healthcare workers and, by extension, to the education of the local population.

The Institute of Medicine reported in 2003 that true population health cannot be achieved until the entire US population has access to adequate healthcare. Some argue that it is the right of every citizen and the responsibility of the federal government to provide some sort of universal coverage. Access to care is key to achieving basic levels of health, including mental health, dental health, and care of chronic conditions. The ACA attempted to improve access to care for millions of Americans. A 2018 Commonwealth Fund survey (Collins, Bhupal, and Doty 2019) paints an evidenced-based picture of the outcomes of the ACA thus far:

In 2018, 45 percent of US adults were inadequately insured, and the adult uninsured rate was 12.4 percent.

In 2018, 45 percent of US adults were inadequately insured, and the adult uninsured rate was 12.4 percent.

Compared with 2010, however, fewer adults were uninsured, and the duration of coverage gaps was shorter.

Compared with 2010, however, fewer adults were uninsured, and the duration of coverage gaps was shorter.

Employer plans provided less coverage in 2018 than they did in 2010, leading to more people with coverage being underinsured.

Employer plans provided less coverage in 2018 than they did in 2010, leading to more people with coverage being underinsured.

More people had difficulty paying their medical bills.

More people had difficulty paying their medical bills.

One success of the ACA is that more adults, including those who are underinsured, are likely to have continuous care and to get regular preventive care. Healthcare plays a role in promoting health policy that influences the determinants of health and positively affects health outcomes.

The Commonwealth Fund report notes that prevention alone is not enough. Policy should expand Medicaid coverage without restrictions and ban insurance plans that do not comply with the provisions of the ACA. The report also argues for the importance of continued federal funding for healthcare navigators. Lifting the income cap to help some afford marketplace plans would bolster population health, as would offering tax credits for high out-of-pocket medical costs. Finally, policy should protect consumers from surprise medical bills and more.

The American Hospital Association (AHA) recognizes the role of healthcare in population health. In 2019, the organization implemented a strategic vision called the “AHA’s Path Forward.” The directive includes five areas of commitment from the AHA:

Access to affordable, equitable health, behavioral, and social services

Access to affordable, equitable health, behavioral, and social services

Providing value to lives with given care

Providing value to lives with given care

Embracing the diversity of individuals and serving as their health partners

Embracing the diversity of individuals and serving as their health partners

Focusing on the well-being of individuals with community resources

Focusing on the well-being of individuals with community resources

Coordinating seamless care

Coordinating seamless care

The AHA plan offers a picture of strategic priorities and what it calls “driving forces,” such as payment for value, chronic care management, and population health management (AHA 2019). The effort is supported by ideas and resources from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in a “playbook” that fosters partnerships between hospitals and community partners (Health Research and Educational Trust 2017).

The American Medical Association includes in its tagline that it “promotes the art and science of medicine and the betterment of public health.” Medical schools have only recently begun to include population health in their curricula. The idea of gathering evidence and then collaborating with community organizations to improve social determinants of health is a relatively new concept in most medical schools.

Changing the focus of the healthcare industry to emphasize population health is a slow process. Davis Nash, a physician and dean of the Jefferson College of Population Health in Philadelphia, gave the industry’s effort a C grade in 2016, but in 2019, he upgraded his assessment to a B or B+. Nash indicates progress in those three years, noting that several schools and departments of population health have been established in medical schools (Squazzo 2019).

DEBATE TIME The Healthcare Industry and Population Health

DEBATE TIME The Healthcare Industry and Population Health

Some argue that the healthcare industry should be more involved with population health, even partnering with public health agencies and other stakeholders to keep their communities well. What do you think? Form two teams and debate the merits of such an idea. One team could focus on the positives of involving healthcare professionals as team members or even taking the lead on population health. Another team could argue that healthcare professionals should worry about the sick, not the well. Hospitals, for example, may not make a profit or even achieve a reasonable budget if too much is spent on community health.

SUMMARY

Population health is defined as health outcomes of groups or individuals, including the distribution of those outcomes by social demographics, location, and other factors. Population health considers the links between health outcomes, determinants of health, and health policies and interventions. It differs from public health, which focuses on assessment, policy development, and assurance.

Determinants of health are factors that are drivers of health outcomes. They are key to understanding the health of populations. Determinants of health are divided into five categories: medical care, individual behavior, social environment, physical environment, and genetics. Social and physical environment together are referred to as social determinants of health. Evidence gathered over the past 25 years has demonstrated the significance of socioeconomic factors such as income, wealth, and education as causes of a variety of health problems.

Health disparities are preventable differences among population groups in the burden of disease or injury. Health disparities occur when one population group is not afforded equal or fair treatment or the burden of disease or injury falls disproportionately on certain populations. Data clearly identify health disparities in the areas of race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, age, location, gender, disability status, and sexual orientation. Health disparities impose a financial burden on the entire population, resulting in $93 billion in excess medical care costs and $42 billion in lost productivity.

Big data and analytics are used to create models for improving population health. Healthcare organizations have billions of gigabytes of data at their disposal to analyze the needs of the populations they serve. Finding individuals with the skills to gather and analyze data and create analytical models, however, is a barrier to progress. For that reason, healthcare systems have been slow to use analytics to solve population health challenges.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires tax-exempt hospitals to focus on population health by completing a community health needs assessment (CHNA) and improvement plan every three years. THE CHNA prioritizes the needs of the community and identifies resources to address them. Public health agencies that wish to be accredited must meet the same requirements.

Two other tools for population health management are the County Health Rankings produced by the University of Wisconsin’s Population Health Institute and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Healthy People initiative of Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, an agency of the US Department of Health and Human Services. These tools provide analysis and benchmark data to healthcare providers, public health agencies, and the general public. The County Health Rankings provide county-level data on life expectancy and quality of life (health outcomes) based on a set of health factors. Local data are compared with state data and top performers nationally to promote debate and set agendas for population health improvement.

Healthy People is a decades-old effort to set national population health objectives. Efforts are now underway for the introduction of Healthy People 2030. Each Healthy People initiative establishes several topic areas and hundreds of objectives, supported by baseline national data and targets for improvement.

Whether it is training healthcare workers to teach clients health promotion and disease prevention or taking care of their own employees, healthcare plays a major role in population health. That role extends to the communities served by these systems. Health policy and government are also key to population health improvement. The Institute of Medicine noted nearly two decades ago that true population health cannot be achieved until the entire US population has access to healthcare. Fewer people today are uninsured than before the enactment of the ACA, but more are underinsured.

The American Hospital Association, the American Medical Association, and other healthcare organizations support population health management. Medical schools include it as the “third pillar” of medical education. Moving healthcare toward an increased emphasis on population health is a slow process.

QUESTIONS

- What is the difference between public health and population health?

- What are some examples of determinants of health?

- Give two examples of how social determinants of health affect health outcomes.

- What are health disparities?

- What are some examples of health disparities?

- How do analysts use “big data” in healthcare?

- What is the purpose of the community health needs assessment (CHNA)?

- The study that compares health outcomes and health factors at a county level is called what?

- What are the goals of the Healthy People 2020 initiative?

- What is required for true population health, according to the Institute of Medicine?

ASSIGNMENTS

- The 500 Cities Project is a collaboration between CDC, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the CDC Foundation. The project provides a variety of health data at the city or census tract level that may motivate stakeholders to take action. Visit the 500 Cities home page at www.cdc.gov/500cities/index.htm. Use the interactive map to find an area close to you. Zoom in on two or three small zones. Report at least one key measure (use the pulldown menu on the left side of the map to choose a measure).

- Go to the Healthy People website at www.healthypeople.gov. Using the tools on the Healthy People home page, find a topic area of your choice. Identify two objectives within that topic. Report on the baseline data and the target reported for those objectives.

- The County Health Rankings help identify social determinant needs at the county level. Go to www.countyhealthrankings.org and scroll down to identify a state on the interactive map. Choose a county in that state. How do the county’s health outcomes (length of life and quality of life) compare with the rest of the state and the top US performers? Identify three health factors that you think the county should focus on improving.

CASES

MATERNAL MORTALITY IN LOUISIANA

Officials at the Louisiana Department of Health are staring at the facts: Black women in the state are four times more likely to experience a pregnancy-related death than white women. Healthy People 2020 set a national goal of 11.4 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. In 2018, Louisiana experienced 47.2 deaths per 100,000 among non-Hispanic/Latino Black women (AHR 2019).

As the department’s experts looked more closely at the data, they found that the color of a woman’s skin makes a difference when it comes to the care she receives, such as blood transfusions. The data made clear that bias and low-quality care are significant issues in Louisiana’s healthcare systems (Donovan 2019).

Discussion Questions

- What options are available to the Louisiana Department of Health in terms of population health directives or initiatives?

- What specific steps could the Louisiana Department of Health take in working with the state’s healthcare providers?

THE GOOD NEIGHBOR

Olivia, the new CEO of Mountain West Hospital, is taking time to meet local community leaders and show them that she wants to be a partner in making the community a great place to live. One of her key initiatives is to examine the general health of the community and learn how her organization can support the local health department and similar organizations. She knows that the Affordable Care Act requires nonprofit hospitals to complete a community health needs assessment, but Mountain West is part of a privately owned corporation, so it is not subject to that requirement. Clark has scheduled a meeting with her leadership team to discuss the hospital’s role in the local population’s health.

Discussion Questions

- What steps should Clark take as she begins her efforts to improve the health of the community?

- Find and describe some of the tools available to Clark that might help her analyze the needs of the community and prioritize the programs she puts in place.

REFERENCES

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). 2019. 2018 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. Published September. www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/research/findings/nhqrdr/2018qdr.pdf.

———. 2017. 2016 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. Published October. www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr16/index.html.

Ahrens, K., B. Haley, L. Rossen, P. Lloyd, and Y. Aoki. 2016. “Housing Assistance and Blood Lead Levels: Children in the United States, 2005–2012.” American Journal of Public Health 106 (11): 2049–56.

American Hospital Association (AHA). 2019. “Strategic Plan: AHA Path Forward.” Accessed June 18, 2020. www.aha.org/2017-12-11-strategic-plan-aha-path-forward.

American Public Health Association (APHA). 2020. “What Is Public Health?” Accessed June 18. www.apha.org/what-is-public-health.

America’s Health Rankings (AHR). 2019. “Maternal Mortality.” Accessed June 22, 2020. www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/health-of-women-and-children/measure/maternal_mortality_a.

Arndt, S., L. Acion, K. Caspers, and P. Blood. 2013. “How Reliable Are County and Regional Health Rankings?” Prevention Science 14: 497–502.

Artiga, S., and E. Hinton. 2018. “Beyond Healthcare: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity.” Kaiser Family Foundation. Published May 10. www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/.

Association for Community Health Improvement (ACHI). 2017. “Community Health Assessment Toolkit.” Accessed June 18, 2020. www.healthycommunities.org/Resources/toolkit.shtml#.XRZSUSBMGUk.

Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO). 2019. Developing a State Health Improvement Plan: Guidance and Resources: A Companion Document to ASTHO’s State Health Assessment Guidance and Resources. Accessed June 18, 2020. www.astho.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=6597.

———. 2017. “Community-Based Health Needs Assessment Activities: Opportunities for Collaboration Between Public Health Departments and Rural Hospitals.” Accessed June 18, 2020. www.astho.org//uploadedFiles/Programs/Access/Primary_Care/Scan%20of%20Community-Based%20Health%20Needs%20Assessment%20Activities.pdf.

Banerjee, T., D. Crews, D. Wesson, S. Dharmarajan, R. Saran, N. Riso Burrows, S. Saydah, and N. Powe. 2017. “Food Insecurity, CKD, and Subsequent ESRD in U.S. Adults.” American Journal of Kidney Diseases 70 (1): 38–47.

Beckles, G., and C. F. Chou. 2016. “Disparities in the Prevalence of Diagnosed Diabetes—United States, 1999–2002 and 2011–2014.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 65 (45): 1265–69.

Bower, C. 2009. Guide and Template for Comprehensive Health Improvement Planning: Version 2.1. Connecticut Department of Public Health Planning Branch, Planning and Workforce Development Section. Published June. www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/Programs/Public-Health-Infrastructure/CHIP-Guide.pdf.

Bradley, P. 2013. “Implications of Big Data Analytics on Population Health Management.” Big Data 1 (3). https://doi.org/10.1089/big.2013.0019.

Braveman, P., and L. Gottlieb. 2014. “The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Cause of the Causes.” Public Health Reports 129 (Suppl. 2): 19–31.

Breiding, M., K. Basile, J. Klevens, and S. Smith. 2017. “Economic Insecurity and Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Victimization.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 53 (4): 457–64.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2019a. “CDC Research on SDOH.” Updated December 12. www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/research/index.htm.

———. 2019b. “Resources Organized by Essential Services.” Published March 7. www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/10-essential-services/resources.html.

———. 2019c. “What Is Population Health?” Published July 23. www.cdc.gov/pophealthtraining/whatis.html.

———. 2018. “Social Determinants of Health: Know What Affects Health.” Published January 29. www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/index.htm.

———. 2015. “Assessment & Planning Models, Frameworks & Tools.” Published November 9. www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/cha/assessment.html.

———. 2013. “CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report—United States, 2013.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 62 (3 Suppl.) www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/other/su6203.pdf.

Chetty, R., M. Stepner, and S. Abraham. 2016. “The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014.” JAMA 315 (16): 1750–66.

Collins, S., H. Bhupal, and M. Doty. 2019. “Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA.” Commonwealth Fund. Published February 7. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/feb/health-insurance-coverage-eight-years-after-aca.

Donovan, J. 2019. Speech delivered at the Association of University Programs in Health Administration Annual Conference, New Orleans, June 12.

Evans, R., M. Barer, and T. Marmor. 1994. Why Are Some People Healthy and Others Not? The Determinants of Health of Populations. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Evans, R., and G. Stoddart. 1990. “Producing Health, Consuming Healthcare.” Social Science & Medicine 31 (12): 1347–63.

Falk, L. H. 2017. “Population Health Documentary Highlights Three Success Stories Transforming Healthcare.” HealthCatalyst. Published Sept 29. www.healthcatalyst.com/population-health-documentary-showcases-success-stories.

Gay and Lesbian Medical Association (GLMA). 2006. Guidelines for Care of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients. http://glma.org/_data/n_0001/resources/live/GLMA%20guidelines%202006%20FINAL.pdf.

Greer, S., L. Schieb, M. Ritchey, M. George, and M. Casper. 2016. “County Health Factors Associated with Avoidable Deaths from Cardiovascular Disease in the United States, 2006–2010.” Public Health Reports 131 (3): 438–48.

Health Canada. 1998. Taking Action on Population Health. Ottawa, Ontario: Health Canada.

Health Research and Educational Trust. 2017. A Playbook for Fostering Hospital-Community Partnerships to Build a Culture of Health. Published July. www.hpoe.org/Reports-HPOE/2017/A-playbook-for-fostering-hospitalcommunity-partnerships.pdf.

Helms, V., B. King, and P. Ashley. 2017. “Cigarette Smoking and Adverse Health Outcomes Among Adults Receiving Federal Housing Assistance.” Preventive Medicine 99: 171–77.

Institute of Medicine. 2003. The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Intermountain Medical Center (IMC). 2016. 2016 Community Health Needs Assessment. Accessed June 19, 2020. https://intermountainhealthcare.org/about/who-we-are/chna-reports/-/media/37084070bfb24140acbddde5efc3d5cc.ashx.

Internal Revenue Service (IRS). 2019. “Community Health Needs Assessment for Charitable Hospital Organizations—Section 501(r)(3).” Updated September 20. www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/community-health-needs-assessment-for-charitable-hospital-organizations-section-501r3.

Kanarek, N., H. L. Tsai, and J. Stanley. 2011. “Health Ranking of the Largest U.S. Counties Using the Community Health Status Indicators Peer Strata and Database. Journal of Public Health Management Practice 17: 401–5.

Kent, J. 2018. “Big Data to See Explosive Growth, Challenging Healthcare Organizations.” Health IT Analytics. Published December 3. https://healthitanalytics.com/news/big-data-to-see-explosive-growth-challenging-healthcare-organizations.

Kindig, D., and G. Stoddart. 2003. “What Is Population Health?” American Journal of Public Health 93 (3): 380–83.

Kindig, D., Y. Asada, and B. Booske. 2008. “A Population Health Framework for Setting National and State Goals.” JAMA 299 (17): 2081–83.

Luy, M., M. Zannella, C. Wegner-Siegmundt, Y. Minagawa, W. Lutz, and G. Caselli. 2019. “The Impact of Increasing Education Levels on Rising Life Expectancy: A Decomposition for Italy, Denmark, and the USA.” Genus: Journal Population Sciences 75 (11). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-019-0055-0.

Mathews, T. J., and M. F. MacDorman. 2013. “Infant Mortality Statistics from the 2009 Period Linked Birth/Infant Death Dataset.” National Vital Statistics Report 61: 1–28.

McGinnis, J., P. Williams-Russo, and J. Knickman. 2002. “The Case for More Active Policy Attention to Health Promotion.” Health Affairs 21 (2): 78–93.

McPhillips, D. 2018. “The Relationship of Race to Community Health.” U.S. News & World Report. Published September 25. www.usnews.com/news/healthiest-communities/articles/2018-09-25/the-burden-of-race-on-community-health-in-america.

National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO). 2020. “Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (MAPP).” Accessed June 19. www.naccho.org/programs/public-health-infrastructure/performance-improvement/community-health-assessment/mapp.

National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2018. “National Health Interview Survey, Table P-1: Respondent-Assessed Health Status, by Selected Characteristics: United States, 2018.” Accessed June 19, 2020. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/NHIS/SHS/2018_SHS_Table_P-1.pdf.

National Institutes of Health (NIH). 2020. “How Sex/Gender Influence Health & Disease (A–Z).” https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sex-gender/sexgender-influences-health-and-disease/how-sexgender-influence-health-disease-z.

———. 2019. “How Sex and Gender Influence Health and Disease.” Accessed June 19, 2020. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sites/orwh/files/docs/SexGenderInfographic11x17_508_Final_2.pdf.

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP). 2020a. “About Healthy People.” Accessed June 18. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/About-Healthy-People.

———.2020b. “Educational and Community-Based Programs.” Accessed June 18. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/educational-and-community-based-programs/objectives.

———. 2020c. “History & Development of Healthy People.” Accessed June 18. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/About-Healthy-People/History-Development-Healthy-People-2020.

———. 2020d. “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health.” Accessed June 18. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health#one.

———. 2013. “Healthy People 2020 at Work in the Community: Door-to-Door Program.” Published March 29. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/healthy-people-in-action/story/healthy-people-2020-work-community-door-door-program.

Oliver, T. 2010. “Population Health Rankings as Policy Indicators and Performance Measures.” Preventing Chronic Disease 7(5): A101.

Orgera, K., and S. Artiga. 2018. “Disparities in Health and Healthcare: Five Key Questions and Answers.” Kaiser Family Foundation. August 8. www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/disparities-in-health-and-health-care-five-key-questions-and-answers/.

Public Health Image Library (PHIL). 2017. “Image 22746.” Accessed June 21, 2019. https://phil.cdc.gov/Details.aspx?pid=22746.

Remington, P., B. Catlin, and K. Gennuso. 2015. “The County Health Rankings: Rationale and Methods.” Population Health Metrics 13: 11.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2019. 2019 County Health Rankings Key Findings Report. Published March. www.countyhealthrankings.org/reports/2019-county-health-rankings-key-findings-report.

Semega, J., K. Fontenot, and M. Kollar. 2017. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2016. Current Population Reports, US Census Bureau. Published September. www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2017/demo/P60-259.pdf.

Squazzo, J. 2019. “Population Health Turned Inward: Employee Health Successes.” Healthcare Executive, July/August, 8–14.

Sucich, K. 2019. “HIMSS Analytics Survey Sponsored by Dimensional Insight Finds Only 1 out of 5 Healthcare Organizations Using Analytics for Population Health.” News release, June 28. www.prweb.com/releases/himss_analytics_survey_sponsored_by_dimensional_insight_finds_only_1_out_of_5_healthcare_organizations_using_analytics_for_population_health/prweb16271453.htm.

Terry, K. 2013. “Analytics: The Nervous System of IT-Enabled Healthcare.” iHT2. Published May 16. http://ihealthtran.com/iHT2analyticsreport.pdf.

Turner, A. 2018. “The Business Case for Racial Equity: A Strategy for Growth.” W. K. Kellogg Foundation. Published April. https://altarum.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-publication-files/WKKellogg_Business-Case-Racial-Equity_National-Report_2018.pdf.

University of Kansas. 2018. “Assessing Community Needs and Resources.” Community Tool Box, Center for Community Health and Development, University of Kansas. Accessed June 19, 2020. https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/assessment/assessing-community-needs-and-resources.

Utah Department of Health. 2016. Utah Health Improvement Plan 2017–2020: A Healthier Tomorrow, Together. https://ibis.health.utah.gov/pdf/opha/publication/UHIP.pdf.

Ward, B., J. J. Dahlhamer, A. Galinsky, and S. Joestl. 2014. “Sexual Orientation and Health Among U.S. Adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2013.” National Health Statistics Reports 77. Published July 15. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr077.pdf.

Weber-Morgan Health Department. 2016. Community Health Improvement Plan 2016–2020. Accessed June 19, 2020. www.webermorganhealth.org/about/documents/CHIP_2017.pdf.

World Health Organization (WHO). 2000. “World Health Organization Assesses the World’s Health Systems.” Accessed June 19, 2020. www.who.int/whr/2000/media_centre/press_release/en/.