![]()

keep time see time.

kettledrum see drum.

key (A) The key is fundamental to the practice and understanding of Western tonal music from the early modern period to the present day. It governs melodic contour and harmonic vocabulary. In his A New Way of Making Fowre Parts in Counterpoint (c.1614), Campion was in no doubt about its importance:

Of all things that belong to the making up of a Musition, the most necessary and usefull for him is the true knowledge of the Key or Moode, or Tone, for all signifie the same thing, with the closes belonging unto it, for there is no tune that can have any grace or sweetnesse, unlesse it be bounded within a proper key, without running into strange keyes which have no affinity with the aire of the song.

(A New Way, c.1614, D4r)

Before the sixteenth century, the relationships of pitches in music was controlled by the system of modes, of which there were eight. During the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, the theory of keys gradually replaced modes. To begin with only six or seven keys were commonly notated. It was not until the early eighteenth century that the complete twenty-four were used in a systematic and interconnected way through the so-called ‘Circle of Fifths’.

Key depends on certain defining elements, namely the behaviour of the bass, the cadences or closes used, the start and finish pitches of a piece and the sharps and flats employed. Elizabethan theorists were aware of these principles to varying degrees. Dowland stressed the importance of the start pitch and possibly the harmony: ‘A Key is the opening of a Song, because like as a Key opens a dore, so doth it the Song’ (Micrologus, 1609, p. 8). Morley was very anxious, like Campion, that a piece should begin and end in the same key and that modulation (to a strange key) was forbidden:

A great fault, for every key hath a peculiar ayre proper unto it selfe, so that if you goe into another then that wherein you begun, you change the aire of the song, which is as much as to wrest a thing out of his nature, making the asse leape upon his maister and the Spaniell beare the loade . . . . if you begin your song in D sol re, you may end in a re and come againe to D sol re, etc.’

(Introduction, 1597, p. 147)

The start and finish key area became known as the tonic and was determined by the predominant pitch of the melody and the bass. The particular use of accidentals (sharps and flats) not only helped identify keys, it distinguished between major and minor keys, each with their own characteristics of mood. Morley warned against writing in the wrong key and the use of unusual accidentals: ‘The musick is in deed true, but you have set it in such a key as no man would have done . . . wheras by the contrary if your song were prickt [i.e. notated] in another key any young scholler might easilie and perfectlie sing it’ (ibid., p. 156).

The choice of key could also indicate the types of voices intended depending on the arrangement of clefs. Morley stated that there were two combinations: ‘All songs made by the Musicians, who make songs by discretion, are either in the high key or in the lowe key’ (Introduction, 1597, p. 165). The different vocal ranges were thereby accommodated. A high-key voice was therefore one in its upper range or compass; a low-key voice occupied its low register.

(B) The instances of ‘key’ as musical metaphors in Shakespeare are all of a theoretical nature, for example in The Two Noble Kinsmen, when one of the three queens whose husbands have been killed by Creon appeals to Hippolyta and asks her to convince Theseus to fight against Creon. Although the Queen of the Amazons is renowned for her military achievements, she should speak to Theseus ‘in a woman’s key’ (1.1.94) and even cry to be more persuasive. Here, emphasis is laid on the relationship between key and pitch (women’s key is high-pitched); moreover, Hippolyta must be careful not to change the key, i.e. the tone of her plea to Theseus, and not to let her combative side emerge.

Interestingly, the relationship between Theseus and Hippolyta is explored using a similar metaphor in an earlier play, A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Four days before their wedding, the Duke of Athens tells Hippolyta:

Hippolyta, I woo’d thee with my sword,

And won thy love doing thee injuries;

But I will wed thee in another key,

With pomp, with triumph, and with revelling.

(1.1.16–19)

In this case a change of key – from the martial to the nuptial – is vital in order to reach lasting balance between them.

The concept of harmony derived by singing in the same key is found in another metaphor in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Helena remembers with nostalgia the days when she and Hermia were good friends and both sang ‘in one key’ (3.2.206) as if their voices ‘had been incorporate’ (208). In Much Ado About Nothing, the same idea is put forward once again. Benedick expresses puzzlement at Claudio’s appreciative comments about Hero and asks him: ‘Come, in what key shall a man take you to go in the song?’ (1.1.185). Benedick is wondering if Claudio is serious or whether he is joking, and wishes he could be in tune with him.

In the concluding scene of The Comedy of Errors, Egeon asks Antipholus of Ephesus (whom he mistakenly believes to be Antipholus of Syracuse) whether he recognizes his face. When the long-lost twin son replies in the negative, Egeon asks him if he can at least recognize his voice. At his son’s second negative answer, he laments:

Not know my voice! O time’s extremity,

Hast thou so crack’d and splitted my poor tongue

In seven short years, that here my only son

Knows not my feeble key of untun’d cares?

(5.1.308–11)

If the fundamental pitches of the key are uncertain, then the music will go ‘out of key’ and sound discordant. Egeon is implying that grief and care have caused his voice to become feeble and discordant.

See also gamut.

(C) Wilson (ed.), A New Way (2003), p. 59.

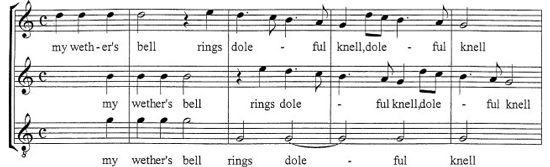

knell (A) The knell is the sounding of a bell rung slowly and solemnly to announce that someone has died. It followed the tolling of the passing-bell which signified that someone was dying or being executed: ‘executions were accompanied by the ballad “Fortune my foe” whose mournful tune was intoned to the baleful burden of the passing-bell’ (Wulstan, p. 49). The knell was rung intermittently, in pairs of notes, sometimes as a burden to a six-note peal (presumably muffled) as is attested by several keyboard pieces (e.g. ‘The buriing of the dead’ interpolated from Elizabeth Rogers Virginal Book BL Add MS 10337 into Byrd’s ‘The Battell’; the ‘knell’ in ‘A Batell & no Battell’ attributed to Bull, MB 19, p. 117) and Weelkes’ three-voice setting of ‘In black mourn I’ (The Passionate Pilgrim, 1599) where the knell sounds in the lowest voice on ‘rings doleful knell’ whilst the upper two parts sing the six-note descending figure of the ‘winding bell’:

‘Knell’ is also used figuratively as a portent of death or sometimes a doleful cry can stand as a metaphor for the knell or death bell.

(B) The dying Katherine of Aragon urges her usher to

Cause the musicians play me that sad note

I nam’d my knell, whilst I sit meditating

On the celestial harmony I go to.

(H8 4.2.78–80)

There follows the stage direction ‘Sad and solemn music’ (80.SD). The practical music (musica instrumentalis) played on the stage helps Katherine in her transition between life and death. Only after her death can she hope to enjoy the perfect harmony created by the music of the spheres (musica mundana), since this is denied to human beings in their mortal state.

At the end of his famous monologue preceding the murder of Duncan, Macbeth hears the bell ring (Mac 2.1.61.SD) – his wife’s signal that the time is right to commit regicide – and observes:

I go, and it is done; the bell invites me.

Hear it not, Duncan, for it is a knell,

That summons thee to heaven or to hell.

(62–4)

This powerful musical metaphor portending death acquires even more significance since it has a concrete aural counterpart in performance.

Another interesting metaphorical use of the term is found in Henry VIII, when two gentlemen talk about Buckingham’s reaction when he heard his sentence of death:

When he was brought again to th’bar, to hear

His knell rung out, his judgement, he was stirr’d

With such an agony he sweat extremely,

And something spoke in choler, ill, and hasty.

(2.1.31–4)

Reading out the death sentence sounds like the ringing of a death bell to the fated Duke.

Leontes, convinced that his wife Hermione is pregnant with Polixenes’ child, reflects that he will be pursued by the disgrace of cuckoldry till his dying day: ‘contempt and clamor / Will be my knell’ (WT 1.2.189–90). In his fit of unfounded jealousy, Leontes juxtaposes the two contrasting concepts of knell and clamour.

Lucrece’s sense of inconsolable sadness is touchingly described in musical terms:

For sorrow, like a heavy hanging bell,

Once set on ringing, with his own weight goes;

Then little strength rings out the doleful knell.

(Luc 1493–5)

The hopelessness possessing her soul has drawn her into a spiral of despair which she can only overcome by committing suicide – the ‘doleful knell’ aptly anticipating her fate.

Ariel’s song ‘Full fathom five’ (Tmp 1.2.397–405), which leads Ferdinand to believe that his father has drowned in the shipwreck, makes reference to ‘sea-nymphs [who] hourly ring his knell’ (403). Another song, ‘Tell me where is fancy bred’, which accompanies Bassanio’s choice of casket (MV 3.2.63–72) contains the line ‘Let us all ring fancy’s knell’ (70). Duffin notes that these two songs have a similar versification, and that the term ‘knell’ as well as the refrain ‘ding dong bell’ appears in both, and conjecturally sets ‘Tell me where is fancy bred’ (for which no tune survives) to the music of ‘Full fathom five’ (p. 381).

(C) Duffin, Shakespeare’s Songbook (2004).

Wulstan, Tudor Music (1985)

knock see strike.

knoll’d see bell; knell.