CHAPTER TWO

THE FOREST OF CORA

After breakfast, Legacy spent a few hours entertaining the littles. They gathered around her, sitting cross-legged on the tumbled stone floor, and Legacy read to them from the book of Cora stories.

It was a bit battered by time, its corners softened and its pages yellowing at the edges. It would have been impossible for her father to find a new copy, because newer copies didn’t exist. Under Silla, in the months after the Great Fire had been put out, the senate had banned worship of the old gods. Too many acts of destruction had been perpetrated in their names.

But enforcement was not as strict in the provinces as it was in the city, and there were ways to find old books and relics. And what harm could there be, Legacy thought, in reading some stories to keep the littles distracted? It wasn’t as if she were invoking the gods to use their powers. She wasn’t asking the gods to alter the weather. She was only describing their adventures for the entertainment of the littles.

The old book was as heavy as an armload of bricks. And though the pages were dusty and torn, the illustrations were painted with luminous mineral pigments: gold, aquamarine, vermilion, and pink. Most of the stories were set in the Forest of Cora. It was unburned then, and the trees in the pictures—nipperberries and cycapresses, but most of all the glorious drammus trees that used to be the pride of the forest—were verdant and teeming with life, nothing like the burnt husks that now lined the hillsides. The trunks of the drammus trees were gargantuan, composed sometimes of six or seven trunks braided together, and their branches cascaded down, trailing leaves like shredded green banners.

In the pictures of the forest, you could see the occasional pyrus, one of Cora’s winged horses. They were furry and gray, with white markings, gentle eyes, and enormous pink wings. There were also illustrations of the lurals that stalked the forest undergrowth, savage animals with the spotted coats of leopards and the blue eyes and sickled fangs of wolves.

Sometimes, the pictures showed lurals leaping toward pyruses, who reared away, breathing fire as they did when threatened.

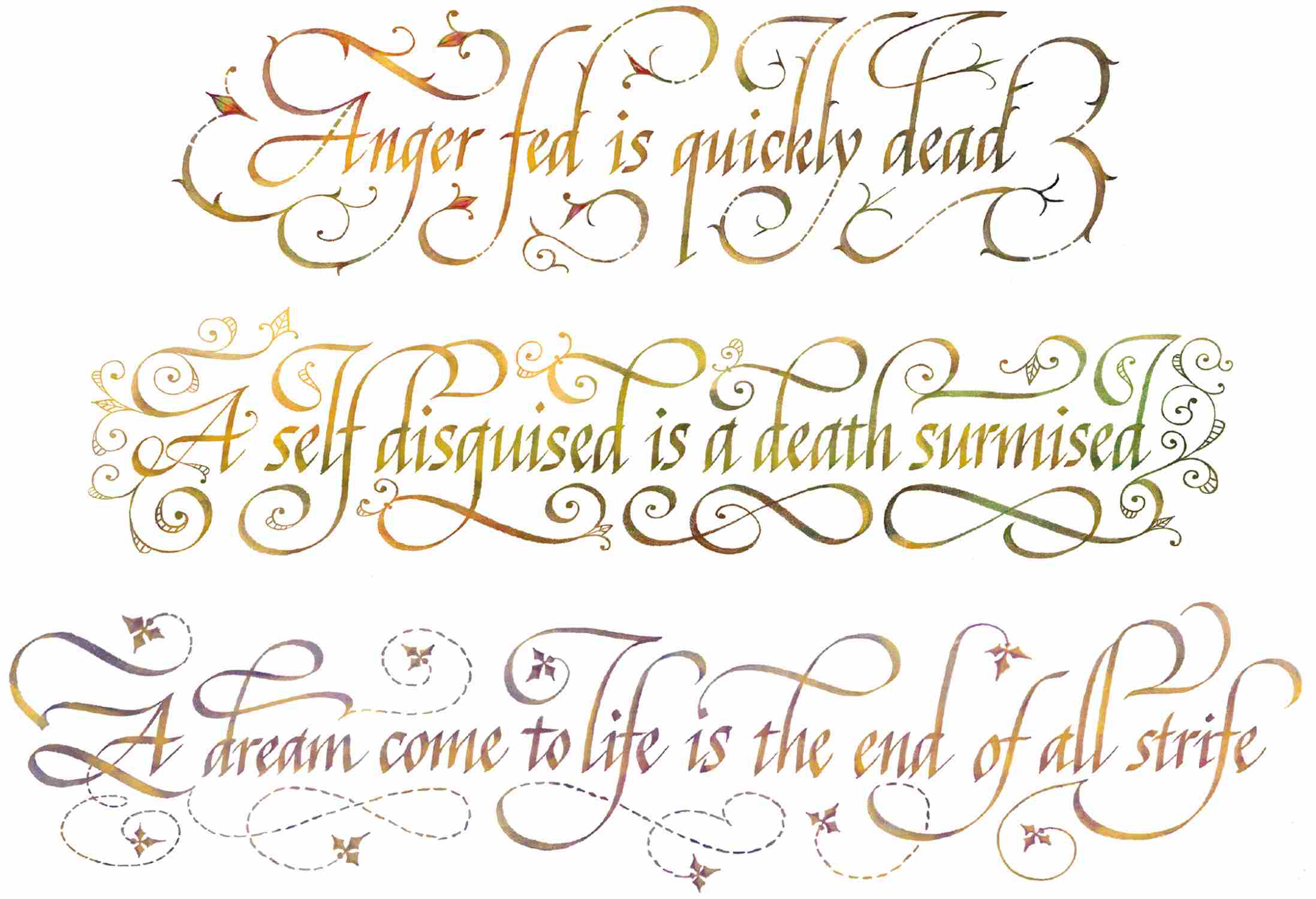

At the ends of the stories, in complicated calligraphy, there were always strange, inexplicable morals, their lettering illuminated in gold: phrases like

Legacy didn’t always understand these morals, and she imagined the littles didn’t, either, but they liked the sounds of the words. They liked the big, brilliant pictures. Before long, Ink was rushing around in her cape, ordering the older littles to take their places onstage.

“You’re Metus, the God of Fear!” Ink was saying to Leo when Legacy finally stood and headed off to the stairs. “And I’m Cora, the Goddess of Love!”

“Why am I always Fear?” Leo grumbled, and Legacy started to smile. But then she remembered Van’s face when she hadn’t pulled out the Tempest. She remembered the way he’d tripped on the stairs.

She hoped he’d found his way to the attic. That was where he went to read about the history of the republic in dusty old volumes, snacking on the bits of stale corn cake he was always pulling out of his pockets. He liked to sit in a nest of old, moth-eaten tapestries, dropping crumbs on the tasseled silk pillows.

All the dusty artifacts in the attic were relics of the days when the orphanage had been a country estate. Now the tapestries—once displayed on the walls—had been wound into thick bolts. The throw pillows were discolored by mildew, and the books were warped and water stained. But the attic was still Van’s favorite place in the orphanage. He spent hours up there every day, reading about the old ways: the noble senators who ruled in the peaceful years before the civil war and the tennis champions who came to the city from the provinces and pledged their loyalty to whichever senator most inspired their trust.

As she climbed the stairs, Legacy assumed Van had taken refuge in a dusty tome, so she was surprised when she ran into him in the hallway instead. He was standing outside her father’s bedroom.

When she approached, he put a finger to his lips. He gestured to the crack in the door.

Legacy took a step forward. Through the crack, she could see a stripe of her father. He seemed to be kneeling before a small table that Legacy had never seen. On top of it, there was a figurine, a woman who herself was prostrate in front of a pyrus, her forehead resting on the ground.

“Dear Cora,” her father was saying. “Please guide me.”

Legacy’s mouth dropped open. Was this what a prayer looked like? She’d never seen her father pray. She’d never seen anyone pray, outside of the old books. Prayer, for one thing, was illegal. And her father had always been a believer in balance and reason. The gods were invoked in moments of strong feeling or passion. How could her father be calling to Cora?

“Help me, Cora,” he was saying, “to have the strength to send him to work.”

“Him?” Legacy whispered to Van, but Van lifted his finger again.

“Help me,” her father said, “to know that by sacrificing one, I’ll be able to look after the others.”

Legacy leaned in closer to the crack. She didn’t like this at all. Who did her father plan to send to work? And why was he praying about it? He looked so small, so vulnerable, bent on his knees. He looked almost like a child, as though his adulthood had only been a costume, one that he’d now shed, becoming as helpless as one of the littles.

“And please,” her father said, “help Van to know that I love him.”

Van? Legacy thought. Van?

Her face was growing hot. Her father wanted to send Van to work? But where could he go? He had no education that would be recognized in the city. And what could he do in the provinces, with his limp and his glasses and his skinny arms? He was the smartest kid Legacy had ever met, but he wasn’t the strongest. He could barely manage carrying full pails of milk in from the barn, let alone long days of harvesting olives.

“Help me,” her father was saying, “to have faith that he’ll survive the factories. And that he’ll understand the decision I’ve made.”

A fist clenched in Legacy’s stomach. The factories? Van would never survive it. She’d heard stories of ten-hour shifts, kids not much older than her hauling loads of mineral compounds shipped in from the mines. Pumping the bellows for hours on end, heating the metal until it could be drawn into threads.

When would Van read? How would he finish his education? How could her father imagine Van was suited to that kind of work?

Legacy glanced over her shoulder at Van. Had he known about this scheme? Was that why he wanted her to go play the trials? Now, in the hallway, his face was ashen, but he didn’t speak. She saw again how frail his shoulders were.

Then she remembered that other day. His shoulders had looked frail then, as well, when he was pinned under that branch, struggling to get out. With a rush of shame, Legacy remembered the blinding flash of light and the way the branch had fallen. She’d tried to pull Van out by his shoulders, but she couldn’t manage it until her father came running.

Before Legacy knew what she was doing, she was charging through her father’s door.

“You can’t send him,” she said. “It’s not right.”

Her father pulled himself up. His face had darkened with anger, and suddenly Legacy realized that he was not, in fact, as vulnerable as a child.

And she’d just revealed that she’d been eavesdropping at his door. And on top of that, she’d rushed into his room without his permission.

Looking up at her father’s darkening face, Legacy considered running away. But then, once again, she remembered the day that branch fell and pinned Van.

“Don’t send him,” she said. “Send me instead.”

Legacy saw the clench of her father’s jaw.

“You’re not old enough,” he said.

“He’s only a year older than I am,” Legacy said.

“I need your help here,” her father said.

Legacy’s nails dug into her palms. “Then let me go to Silla’s trials,” she said. “Let me try to win. If I do, I can train at the academy. I can start winning money, and I’ll send it back and—”

“Legacy!” her father said. “Listen to yourself. You’re talking about fantasies. You’re talking about dreams. But this is the real world that we live in. There’s real work to be done. How would I manage the orphanage without you?”

Legacy stared up at him. How could she explain to him how it felt when she played tennis on the back wall? How could she make him understand that playing tennis was the one thing she was made for, that it wasn’t just a dream, that it was the realest of her realities?

“I could do it,” she tried, but she felt her confidence failing. “I could—”

But her father was already shaking his head. “How could you, Legacy? How could you choose this moment to bring up the old argument about tennis?”

Legacy tried to summon a defense and found that she couldn’t.

“You can’t just think about yourself,” her father said. “Think about the littles. There are other people you have to consider.”

Now, no matter how hard Legacy clenched her fists, the tears started to fall. “Please,” she said. “Just let me tr—”

“So stubborn!” her father said. His eyes had gone cold. “Just like your mother.”

A sob ripped through Legacy’s chest. Then she was running away. She passed Van in the hallway, stumbled down the stone stairs, and must have let herself out through the gate, because she was running up the slope to the Forest of Cora, where she pushed her way past the scratching fingers of the burnt trees, heading deeper into the gloom beneath their dead branches.

Once her lungs started burning, Legacy slowed to a walk. Then she looked around. She had never ventured this far into the forest. There were other kinds of trees here, not just the burnt drammus trees that crowded the edges. The trunks of the drammus trees seemed to be made of charcoal: satiny black and evenly quilted. All of them had been killed in the fire. But some of the other trees seemed to have withstood the worst flames. Here, deeper in the forest, Legacy found a few nipperberry trees that were still bearing fruit. There were other trees too, trees that Legacy didn’t recognize. Some of them had grown leaves since the fire, and their canopies had twisted together until they blocked out the afternoon sunlight. The darkness hung around Legacy’s shoulders like velvet. These trees, the ones she didn’t recognize, seemed wild and unruly. Their trunks were whorled and knotted, their leaves a disorganized jumble of shapes: mittens, goldfish, unfurled umbrellas.

She realized it had been a long time since she’d heard birdsong. She couldn’t hear the explosions deep in the mines, either, or feel their vibrations in the soles of her sneakers. In fact, she could feel nothing but the soft moss underfoot. Its cushiony thickness absorbed the sounds of her footsteps, though sometimes, when she stepped on a burnt branch, she could hear a faint whisper as it disintegrated, giving way to a sigh of black dust.

Everything was so quiet. Legacy wondered if she shouted—if she screamed for help—whether anyone in the world would be able to hear her.

Her heart beat faster as her eyes adjusted to the darkness. Disturbing new details began to emerge from the gloom. If she looked too long at the whorled trunks, she saw the shapes of unhappy faces etched into their bark: women with long, snarled hair; men with skin sagging loose on their faces.

As her ears got used to the new silence, she began to make out sounds that she hadn’t noticed: branches clicking like fingernails on a window, small animals skittering over tangled roots. Then a large shape rushed screeching toward her head, only veering away at the last moment with a great crashing through the canopy.

Spooked, Legacy tried to steady herself by grabbing a low-hanging branch. But she only managed to break off a burnt twig, and then her heart froze in her chest when she heard a moan of pain from the branch she’d just broken.

She looked down at her hand. A drop of blood gleamed on the twig she was holding.

For a moment, Legacy stood rooted to the spot. Was it her hand or the twig that was bleeding? When she looked up again, the tree was bending toward her: a tall, treacherous form leaning down to enclose her. Recoiling in horror, she shook free and ran until she emerged into a clearing.

There, Legacy stopped. She took a step forward. Her jaw dropped.

The clearing looked almost like a tennis court.

It was wild and overgrown, but still: it had the rectangular shape of a court. There, almost obscured by the overgrown grass, were faded white lines. And there, at the center, was a sagging black net.

Legacy took another step forward. What was this place? Who could have built a court so deep in this forest?

More questions bloomed in Legacy’s mind as she walked the length of the court, following its alley line. Who had played here? Who had maintained it so far away from the city? Mowing it, painting its lines, tending it every day until one day he—or she—stopped?

At the drooping net, Legacy paused. Her eyes were drawn to the place where a referee chair would have stood, in pictures she’d seen of the academy courts. In its place, however, there was a gargantuan tree. Its trunk seemed to be built of five thick, braided strands. Its branches drooped down, swaying gently in the breeze. And its leaves—though spare and somewhat tattered—hung from its branches like shredded green banners.

Stunned, Legacy walked across the court. All the drammus trees were said to have burned. They’d gone extinct in the fire. There wasn’t a living one left in the republic.

And yet, there it was. She could hear the whispering of its long, graceful branches swaying slightly in the breeze. It almost sounded as if they were speaking to her softly, beckoning her to come closer.

At the base of the tree, she found a place to sit among the thick, knotted roots. Then she closed her eyes and breathed in. That scent—she was sure she remembered it. It was sweet, like honey, and green as grass. It made her heart grow warm in her chest. She’d almost placed it when one of the branches brushed her cheek.

Its leaves were soft as the finest silk. And the whispering of its branches almost sounded like those strange morals from the book of stories: Anger fed is quickly dead. A dream come to life is the end of all strife.

Then, keeping her eyes closed, listening to that whispering voice, feeling the gentle touch of those leaves, Legacy heard her mother.

“Go,” her mother whispered. “Go to the trials.”

Legacy’s eyes startled open. She looked around. And already, tears were starting to prick.

Because of course it hadn’t been her mother’s voice.

Her mother hadn’t come back. Legacy was alone in the clearing.

But it was her mother’s scent she was smelling. She knew that as surely as she knew that she was alone. That was her mother’s scent, from back in those days in the garden, when they’d all played together, laughing and hugging one another.

For several more hours, Legacy remained by the side of the old court, under the canopy of the drammus. It was hard for her to pull herself away. By the time she finally made her way out to the edge of the forest, it was already evening.

In the garden, the cycapress trees twisted into the sky like daggers. The kitchen was full of hulking dark shapes.

When Legacy climbed the stairs to the attic, she found Van in one of his nests. He was eating a corn cake and reading a thick book entitled Metium Mining Mechanics.

For a moment, before he looked up, Legacy watched him. His nose was buried deep in his book on mechanics, but she saw that the book on his lap was deep green. Its cover was made of thick cloth, with an embroidered gold leaf at the center.

“A drammus leaf,” she said, pointing to the green book, but Van gave her an odd look.

“Where?” he said, glancing down. He picked up the green book and flipped through a few pages. His brow was furrowed in confusion. “It’s just a blank book,” he said.

Legacy stared at him. Even from across the attic, she could see writing on the pages. But before she could protest, Van had closed the book and stood up.

“Bud,” he said. “I’m sorry. I know you can’t go. I just—”

“No,” Legacy said, cutting him short. “I’m going.”

Van blinked at her through his crooked glasses.

“Tomorrow,” Legacy said. “I’m going to play in those trials.”