I have been a baker most of my life and crazy about bread since I was a kid, but it wasn’t until I started teaching people how to bake simple breads at home that I really appreciated what fun, and what a sense of achievement almost everyone experiences when they realise, for the first time, what can be done with some flour, yeast, water and a little salt. Breadmaking doesn’t need to be daunting or mysterious and you don’t have to be born a baker. Baking is for everyone. The aim of this book is simply to get you hooked on making bread. I’m not going to delve into the chemistry of breadmaking, analyse the properties of different flours, list masses of equipment or baffle you with complex techniques.

I look at it this way: do you need to know how a carburetor works to learn how to drive a car? No. Well nor do you need to immerse yourself in science to bake a wealth of wonderful breads. All the breads in this book are ones that I bake at home for my family and friends in my standard domestic oven, with my two young boys distracting me as much as they can. I teach them to the people who come to my bread classes, and I love the moment when the baking is finished and we all sit down with the breads we have made, some good cheese and ham and a glass of wine, and relax and enjoy the sense of achievement. I find that people really hate to break the spell – and nothing gives me more pleasure than to hear from them that they have baked the breads again successfully at home, and really enjoyed themselves in the process.

There is another reason for writing this book – the current climate of concern about the quality and safety of the food we eat, and the worry about additives, fat, sugar, salt and obesity. So much of what we eat is produced on a massive scale, with such a long and complicated chain of ingredients, suppliers and processes that many people are turning to smaller, artisan producers and farmers who can supply them with traceable food produced in simple, traditional ways, which they feel that they can have faith in. And what could be more trustworthy than your own bread, baked by your own hands in your own kitchen, using the best quality ingredients you can find? I will never forget the first time I visited a big industrial bakery in Britain, watching the loaves being mixed in minutes with the help of all kinds of ‘improvers’ and additives, and churned out on a massive scale – it gave me the shock of my life. I had never seen anything like it – it was so alien to everything I knew about bread.

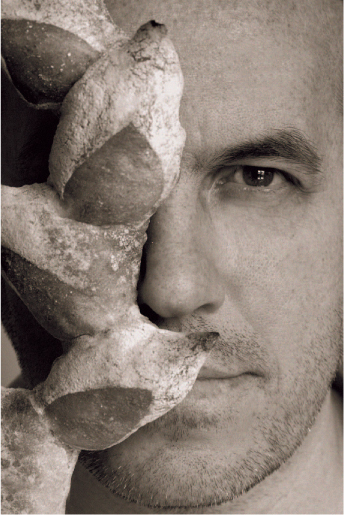

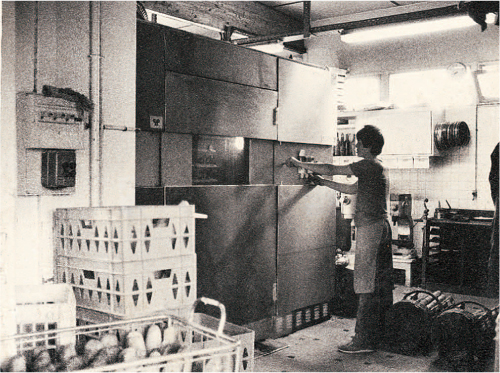

I first fell in love with bread when I was very small. My uncle had a big bakery in Paris, my mother had at one time worked behind a bakery counter, and I was fascinated by the boulangerie in my home town in Brittany. When I was on holiday from school I used to go down there and stand on tip-toes so I could peer over the counter into the bakery itself. I could see the men working in their t-shirts, covered in flour, taking the bread out of the enormous ovens. The warm, yeasty smell was so seductive. When I was 12 or 13 years old I remember being asked in school, ‘What do you want to do when you are older?’ and I replied that I wanted to be a baker. I had a friend whose uncle had a bakery, and he told me that I could come and work with them early one morning. I stayed with my friend in the house above the bakery, but I couldn’t sleep for excitement. By midnight I had crept down – I couldn’t keep away.

Baking was in my blood and, as soon as I could, I did my pre-apprenticeship, spending two weeks at school and two weeks and every weekend in the bakery. French bakeries are hard-working places but they have a magic too. There was a particular moment that I still miss, at around four o’clock in the morning, when the ovens were emptied, and there was no sound, except for the newly baked bread ‘singing’. That’s what we used to call the crackling sound that big loaves make when the crust breaks as it cools down – listen for yourself: when you hear it sing, that’s when you know you have a good crust. In France of course, most people never bake their own bread because the tradition of buying it fresh, every day, is so strong. There is a bread for every occasion: a ficelle for breakfast, a baguette for lunch, a pain de mie for croque monsieur, a bigger pain de campagne or sourdough to put on the table or to keep and toast through the whole week. In France if there is no bread on the table at a mealtime it is a major catastrophe.

In Britain I knew there was a strong tradition of home breadmaking, but when I arrived here in 1988 I was shocked to find that very few people were bothering any more, not because there was a fantastic bakery around every corner, but because the staple diet was the sliced white loaf. There are over 200 varieties of bread available in the UK these days and we buy the equivalent of 9 million large loaves every day, but around 80% of the bread we buy is the sliced, wrapped sandwich loaf – and 75% of that bread is white. Most of the commercially made bread is produced using what is known as the Chorleywood Bread Process, invented in 1961 by the British Baking Industries Research Association at Chorleywood. The process is all about producing a cheap loaf, and it uses high–speed industrial mixers which produce the dough in minutes. Because the flour isn’t necessarily the highest quality, and because you need to add as much water as possible to make the bread more commercially viable, pre-mixed ‘improvers’ and extra ingredients are added, such as emulsifiers, preservatives, fats, antifungal sprays and added enzymes, to make the dough softer, ‘improve’ the volume and prolong shelf life. As there is no real tradition of buying bread daily in Britain, one of the first demands of any mass produced bread is that it will be able to sit on the shelf for up to a week without deteriorating – ‘fresh?’ – that’s not my definition of fresh.

Of course there is a place for commercial sliced bread – to take as bait when you go fishing, or to make a bacon sandwich when you’ve got a hangover! – but if you make your own bread, you needn’t worry about these suspicious ingredients because you are in control – and what do you need? Only flour, yeast, water and salt. No improvers, no enzymes, no stabilisers, emulsifiers or preservatives. And once you see the baking process in its natural, pure form then you can start asking questions to the people who make your bread commercially. Why do they need to add the contents of a chemistry set to your loaf? Skilled bakers can make bread on a large scale without bagfuls of additives, provided people are willing to pay a bit more for their bread – but there lie the two big issues: price and skill. Where have all the bakers gone?

Thankfully I think they are reappearing and, as they do, people are beginning to realise that it is worth paying a little more for the beautiful artisan breads they produce. At last there is a real surge of interest and excitement about breadmaking in this country, which is gathering pace. If I flash back to when I first arrived in Britain, I was amazed to find that in restaurants they seemed to serve bread almost as a canapé, before the meal, then it would be taken away, as if it was something separate from the rest of the food. However, over the last 10–15 years there has been a huge revolution in the way we think about food. And while at first, bread was overlooked in the new wave of excitement about restaurants and cooking, gradually chefs have begun to wake up to the idea that, as soon as someone sits down at the table, the arrival of a selection of breads with different flavours, shapes and textures immediately creates a welcoming and warm atmosphere and an expectation of more good things to follow. And as Britain’s café culture continues to grow, sweet doughs, from croissants to brioche, have come into their own. Of course what happens in restaurants influences the way we cook at home, and I quickly began to see that there was a real desire to bake, which was only held back by the idea that the process must be too complicated or time consuming; something to do on a special occasion with the kids, maybe, but not on a regular basis. That is when I began my breadmaking courses, teaching baking to a cross-section of people, from absolute beginners to those who had tried to make bread once, ended up with something that resembled a brick, and were so disillusioned they never tried again. I never dreamt that the classes would be so popular or so rewarding. I never get tired of seeing people’s faces as their first bread comes out of the oven; they can’t believe that they have made it themselves, without buckets of sweat and frustration.

People often say that those who like to bake and those who like to cook are made in different moulds. Well having worked both as a baker and a chef, I have never thought of baking and cooking as separate activities – to me baking bread is part of making a meal (it’s also the best time to make dough, when the kitchen is warm from cooking) and I can’t imagine dinner on the table without bread. Personally, I would love to see more chefs having a go at making their own bread. And every time I eat out, or talk to a chef about a combination of ingredients, I find myself thinking, ‘I wonder what would be a good bread to go with that?’ or, since bread is a natural carrier of flavours, ‘How would those tastes work in a bread?’

Once you get into the habit of baking regularly, you can always have some bread part-baked in the freezer, ready to be finished off in the oven. Imagine giving your friends freshly baked fougasses, breadsticks or rolls when they come round to dinner; or the children coming home from school and asking for a chunk of fresh bread. Your bread.