Unlike most modern sports, which evolved from other games (as football did from rugby), basketball can be attributed to a single inventor. Dr. James Naismith, a physical education instructor at the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) Training School—now Springfield College—in Springfield, Mass., devised the game in December 1891 as an indoor athletic option for the winter months. Naismith’s invention was a noncontact sport in which two teams of players attempted to toss a soccer ball into peach baskets hung from the railings at opposite ends of the gymnasium. Because the railings were 10 feet high the basket has been forever set at that height.

Basketball was an immediate success, catching on at other YMCAs and schools in the East. Today it is one of the most popular team sports in the United States and throughout the world. Young men and women compete at every level, including playground, youth, scholastic, collegiate, and professional leagues. Spectators throng to arenas to enjoy the game’s fast-paced action and competitive drama.

The rules created by Dr. Naismith are basic to basketball today, though there have been major refinements and notable improvements in the equipment. His original 13 rules included a prohibition against running with the ball. Most formal competition is still held indoors on a wooden floor. Outdoors, the surface is typically made of asphalt or concrete. The court, which varies in size depending on the level of competition, measures up to 94 feet (28.7 meters) long and 50 feet (15.2 meters) wide. It is divided into offensive and defensive halves by a midcourt line. The baskets are metal hoops, or rims, measuring 18 inches (45.7 centimeters) in diameter and set 10 feet (3.05 meters) above the floor. The rims are attached to wood or fiberglass backboards, supported by a post or stanchion, at opposites ends of the court. An open cord net hangs from each rim. An official basketball is 30 inches (76 centimeters) in circumference—slightly smaller for women—inflated with air, and made of leather or rubber.

A basketball team consists of five players plus substitutes and coaches. Each team defends the goal, or basket, at its back. Players advance the ball toward the opposite goal by passing it to a teammate or dribbling it while in motion. Members of the opposing team try to prevent them from scoring a basket. A successful shot at the basket, called a field goal, is generally counted as two points. If attempted from behind a line marked on the floor (the distance varying by level of competition), a successful shot is worth three points. If a shot is missed, usually bouncing off the rim or backboard, a defensive player may catch the rebound and, with teammates, advance the ball toward the opposite basket. An offensive player who captures a rebound may simply shoot again, pass to a teammate, or dribble away. After each basket, possession of the ball goes to the opposing team.

Pushing, holding, and other forms of physical contact are limited. Excessive contact may be called a foul by the referees. If the fouled player was touched while attempting a shot, he is awarded two uncontested attempts at the basket, called foul shots or free throws, from a distance of 15 feet (4.6 meters). Each successful foul shot is worth one point. If a team collectively commits a certain number of fouls in a period of time (five fouls in a professional quarter, seven fouls in a collegiate half), then the other team takes foul shots for every additional infraction.

A pro basketball game has four 12-minute quarters. There are limits on the amount of time a team may take to advance the ball past the midcourt line (8 seconds) and to make an attempt at the basket (24 seconds).

The introduction of metal rims, backboards, nets, and a larger ball—all in the mid-1890’s—fueled enthusiasm for Dr. Naismith’s invention. The new game of basketball was especially popular with young women, and in 1896 the first women’s intercollegiate game was held between Stanford and California. The first men’s college game was contested in 1897, the same year in which five-player teams became standard. A rule change allowing players to dribble was adopted in 1900 (before which players could advance the ball only by passing), adding speed, excitement, and more scoring to the game.

Men’s College Basketball

The sport quickly spread in popularity and early college games had various numbers of players on each side. By 1900 five-a-side was standard. At the 1904 Olympic Games in St. Louis, a number of schools played the first “College Basket Ball Championship”—won by Hiram College of Ohio—and soon this became an annual event sponsored by various groups, eventually evolving in the 1930’s into the annual N.C.A.A. (National Collegiate Athletic Association) men’s basketball tournament, and the N.I.T. (National Invitational Tournament), initially a more prestigious event than the N.C.A.A. title.

The growth of college basketball paralleled that of college football: the sport began as a student-centered and -operated activity, and became at many schools a semiprofessional enterprise with paid coaches running the squads. During the first three decades of the 20th century, the most successful coaches were Joseph Raycroft of the University of Chicago, Walter “Doc” Meanwell of the University of Wisconsin, George Keogan of the University of Notre Dame, and Ward “Piggy” Lambert of Purdue University. Among the outstanding players were John Schommer (Chicago), Charles “Stretch” Murphy and John Wooden (Purdue), and Hank Luisetti (Stanford). In addition, Dr. James Naismith continued to coach for many years at the University of Kansas, and a number of his players became famous coaches: Forrest “Phog” Allen at Kansas and Adolph Rupp at the University of Kentucky.

During its first two decades, college basketball remained a campus sport played mainly in school facilities. In the 1930’s, however, with the popularity of doubleheader games at city arenas, college basketball gained many new fans as well as media attention. Schools in urban areas began to produce some of the best teams: City College of New York (C.C.N.Y.), New York University (N.Y.U.), Long Island University (L.I.U.), and DePaul University in Chicago. The urban influence on college basketball was complex. City schools often had African-American youngsters on their teams and helped integrate the sport, (Jackie Robinson, in fact, played basketball at U.C.L.A. from 1939 to 1941.), but city arenas also attracted large numbers of gamblers and fans betting on games.

The 1940’s should have been college basketball’s best era to date—the sport had become more exciting because of talented big men like George Mikan of DePaul, as well as the increased use of the jump shot and the fast break—but gambling scandals overwhelmed it. Law enforcement agencies discovered that many players on the late-1940’s and early-1950’s championship teams of C.C.N.Y. and Kentucky, and on many other nationally ranked squads, took bribes from gamblers to fix the outcomes of games. Moreover, the players had engaged in fixing games for a number of years, and their coaches, among the most famous in the sport—Clair Bee (L.I.U.), Nat Holman (C.C.N.Y.), and Adolph Rupp (Kentucky)—probably knew about their players’ malfeasance and chose not to report it to the authorities.

Despite the scandals and their repercussions—some players went to prison and some schools deemphasized the sport—college basketball remained popular in the 1950’s, particularly on college campuses in the Midwest and on the West Coast. Outstanding players such as Wilt Chamberlain (Kansas), Oscar Robertson (Cincinnati), and Jerry West (West Virginia) emerged, and such superb teams as the University of San Francisco Dons, led by Bill Russell and K.C. Jones, won N.C.A.A. championships. Toward the end of the 1950’s, John Wooden, the coach at U.C.L.A., began to build excellent squads. Because his school had a history of integration and because he was the first college coach to recruit outstanding players from all regions of the country, his teams came to dominate their conference and then the N.C.A.A. tournament, winning nine out of 10 national titles from 1964 to 1973. Led by such players as Lew Alcindor (later known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), Bill Walton, Walt Hazzard, and Lucius Allen, U.C.L.A. dominated college basketball longer than any school has ever done.

U.C.L.A.’s reign was interrupted in 1966 by Texas Western (now the University of Texas at El Paso). In the N.C.A.A. final game, Texas Western’s all-black starting five

easily beat the all-white Kentucky lineup and, symbolically, ended segregation in college basketball. In 1969 an event with far-reaching consequences occurred when University of Detroit basketball star Spencer Haywood challenged the rule forbidding players from leaving school to play in the N.B.A. before their class graduated. Haywood won his case and changed the future of college basketball; from the 1970’s to the present, increasing numbers of players, including a majority of stars, depart school early for the pros. By the late 1990’s, players were jumping directly from high school to the professional game, bypassing college completely.

The most memorable on-court event of the 1970’s took place in the N.C.A.A. final game of 1979. The Michigan State Spartans, led by Earvin “Magic” Johnson, played the Indiana State Sycamores, featuring Larry Bird. The contest, won by Michigan State, drew the highest TV ratings of any game in college basketball history. It also helped elevate the N.C.A.A. men’s basketball tournament to national event status, now nicknamed “March Madness.”

In the early 1980’s, ESPN began televising a multitude of college basketball games, and this greatly increased the popularity of the sport. The network also prompted the creation of new conferences of universities seeking air time for their teams. The alliance between ESPN and the Big East was particularly fruitful and in the 1980’s helped promote the basketball programs of schools such as Georgetown and Villanova, which won N.C.A.A. titles in 1984 and 1985, respectively. By the end of the decade, the N.C.A.A. signed its first $1 billion-plus contract with a TV network (CBS) to televise the men’s and women’s basketball tournaments. The current contract, a multiyear deal, is worth more than $6 billion.

By 1990, college basketball was awash in money but also in corruption. A shadowy world of “street agents” and under-the-table payments came to exist which continues to the present. Some of the best teams and players participated in the corruption. The University of Michigan’s “Fab Five,” led by Chris Webber, were involved in six-figure under-the-table payments; other schools and players had other problems. Some scandals, such as at the University of Minnesota, involved academic fraud.

Yet, through all the scandals, the fans, especially the students at prominent basketball schools, loved the sport and their teams, and followed them avidly. As a result, many universities built new and grandiose arenas and spent millions on their basketball programs. All of this was far from the game’s modest origins in Springfield, Mass.

On the court, college basketball is similar to the professional game but with several major differences. First is the element of time: a college game stretches over two 20-minute halves, rather than the four 12-minute quarters in its professional version. Furthermore, the shot clock lasts 35 seconds in college rules, compared to 24 seconds in the pros. The longer shot clock and the shorter game mean that college basketball features less scoring than its professional cousin, but in the eyes of many observers, the emphasis on rapid passing and player movement in the collegiate game make for better viewing.

Women’s College Basketball

Women’s college basketball is almost as old as the men’s game; in fact, its earliest proponent, Maude Sherman, married Dr. James Naismith, the sport’s inventor. Unfortunately, because of the Victorian conventions, the rules of women’s basketball were different from the evolving men’s game. Until the 1970’s, most women played what was termed “girl ball”: six players per team, three confined to each half the court, with restrictions on dribbling and ball-handling. Nevertheless, the game thrived in various regions of the country, particularly in high schools and colleges in Iowa and some adjacent states.

In the early 1970’s, the associations in charge of women’s sports sanctioned the use of the five-a-side, full-court game, along with a 30-second shot clock. Then, in 1973, the passage of Title IX, which mandated equal opportunities in college sports for all students, began the transformation of women’s basketball into a major intercollegiate sport. The Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (A.I.A.W.) organized regional tournaments and a national championship; outstanding teams from Delta State University (Mississippi) and Immaculata College (Pennsylvania) emerged, along with stars such as Ann Meyers (U.C.L.A.), Nancy Lieberman (Old Dominion University), and Lynette Woodward (Kansas).

In the early 1980’s the N.C.A.A. pushed the A.I.A.W. aside and took over the sport, promoting the championship tournament on television, and mirroring women’s teams to the men’s squads of their universities (while still permitting underfunding of the women’s teams). From the late 1980’s to the present, those schools willing to fund their women’s teams at a high level have amassed the best records and the most N.C.A.A. titles: the University

of Tennessee, the University of Connecticut, and Stanford have all won multiple crowns.

Professional Basketball

Professional basketball was born in 1898, as several teams began barnstorming the eastern states to compete for pay against local squads. The first collegiate association, the Eastern Intercollegiate League, was formed in 1902. Basketball was introduced as an Olympic demonstration sport in the Summer Games of 1904, spreading interest to Europe and Asia.

Other notable innovations in the early years included a limit of five personal fouls per player per game (1908–09) and a change in the penalty for walking or double-dribbling from foul shots to loss of ball possession (1923). The results were a reduction in rough play and shorter breaks in the action. More changes in the early 1930’s, including the 10-second rule (for advancing the ball past midcourt) and a 3-second rule (prohibiting a player from remaining inside the foul lane), further contributed to the evolution of the game.

1920’s and 1930’s By the 1920’s, basketball tournaments were being held in high schools and colleges across the country. Company teams and touring professionals built grassroots followings. Among the top pro teams of the era were the Original Celtics, featuring such stars as Nat Holman and Joe Lapchick (both of whom would become prominent coaches), and the Harlem Globetrotters, a talented and flamboyant all-black team founded in 1927 by promoter Abe Saperstein. Before the integration of the National Basketball Association later in the century, the Globetrotters frequently beat top teams in invitational events. Later, after the growth and integration of the N.B.A. took away their best players and talent base, the Globetrotters turned into a traveling basketball carnival, and they have entertained audiences in more than 100 countries with their on-court stunts and clowning routines.

It was not until the mid-1930’s, however, with developments at the college level, that basketball began to emerge as a major spectator sport. In 1934 a sportswriter named Ned Irish promoted a college doubleheader at New York’s Madison Square Garden that drew a large crowd. College basketball became a regular event at the Garden and elsewhere, prompting many universities to build arenas or launch programs.

Another turning point came in 1936, when the team from Stanford University traveled east to compete at Madison Square Garden and stunned the basketball establishment with its fast-paced, freewheeling style of play. Stanford featured the dynamic Hank Luisetti, whose running one-handed shot revolutionized offensive play (replacing the standard two-hand set shot) and delighted spectators. With the 1937–38 season came elimination of the jump ball after each field goal, further accelerating the pace of the game.

In 1938 Madison Square Garden held the first major postseason intercollegiate playoff, the National Invitation Tournament (N.I.T.), and the National Collegiate Athletic Association (N.C.A.A.) organized its own championship the following year. The N.I.T. is still held at the end of every season, but the winner of the N.C.A.A. tournament is recognized as the official collegiate champion.

The 1930’s also witnessed the birth of organized competition at the international level. An official governing body, the International Amateur Basketball Federation (FIBA), was established in 1932 in Geneva, Switzerland (later moved to Munich, Germany). In 1936 basketball became a full medal sport for men at the Olympic Games in Berlin, with teams from 22 nations taking part.

1940’s and 1950’s The National Basketball League (N.B.L.), founded in 1937 and based in the Midwest, was the most successful of several early professional leagues. Interest in the pro game lagged until 1946, however, when the new Basketball Association of America (B.A.A.) was launched. With franchises in 11 major cites, including Toronto, the B.A.A. attracted fans eager to see former college players compete. Four N.B.L. franchises jumped to the B.A.A. in 1948, and the expansion was completed in 1949—thereby creating the National Basketball Association. The N.B.A. dates its foundation to the creation of the B.A.A., in 1946. The original N.B.A. included 17 franchises in three divisions. George Mikan of the Minneapolis Lakers, at 6’10” the game’s first great “big man,” was a major gate attraction who helped ensure the success of the league. Mikan dominated the pro game until his retirement in 1956, leading his team to five N.B.A. championships.

Several developments in the early 1950’s—combined with the ever-improving skills of the players—contributed to the growth of the N.B.A. The first black players were drafted into the N.B.A. in 1950. Before the 1954–55 season, the N.B.A. introduced the 24-second rule to eliminate stalling; with more shots came more excitement. The arrival of professional basketball was perhaps most clearly symbolized by the election of the first members of the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1959, a list appropriately headed by Naismith. (The original Hall of Fame building,

located on the campus of Springfield College, did not open until 1968.)

Aside from Mikan’s Minneapolis Lakers (later to become the Los Angeles Lakers), top N.B.A. teams of the 1950’s included the Boston Celtics (champions in 1957 and 1959), Syracuse Nationals (1955), Philadelphia Warriors (1956), St. Louis Hawks (1958), and perennial powers New York Knickerbockers and Fort Wayne Pistons.

The title of the game’s top center passed from Mikan to Bill Russell in the latter part of the decade. After leading the University of San Francisco to N.C.A.A. titles in 1955 and 1956, Russell teamed with passing wizard Bob Cousy and other members of the Boston Celtics in winning the first two of many N.B.A. championships. Other outstanding players of the decade included Bob Pettit, Cliff Hagan, Dolph Schayes, Clyde Lovellette, and “Easy” Ed Macauley.

1960’s By the early 1960’s, the N.B.A. had 10 franchises across the United States, with annual attendance reaching several million. The print and broadcast media expanded coverage, and the game’s top players became highly paid celebrities. As players also increased in height and athletic ability, the style and tempo of play also evolved. The dunk shot, or simply dunk, in which a player leaps high off the floor, extends the ball over the basket, and jams it through the hoop, became a common and crowd-thrilling part of the game. The fast break, featuring skilled dribbling and deft passing at top speed, became another trademark of modern pro basketball.

A new league, the American Basketball Association (ABA), was founded in 1967 with 11 teams. The ABA gained a following by luring graduating college stars or established pros and by introducing such innovations as the three-point shot and a red-white-and-blue ball. The league continued operations until after the 1975–76 season, when its strongest franchises were absorbed into the N.B.A.

The Boston Celtics dominated the N.B.A. in the 1960’s, establishing one of the great dynasties in professional sports by capturing nine titles in 10 years. Coached by Red Auerbach and led by Russell, Cousy, John Havlicek, and a host of other future Hall of Famers, the Celtics demonstrated that smart, unselfish team play wins championships.

Russell’s supremacy at the center position was challenged by a bigger, stronger new talent, the 7’1” Wilt Chamberlain. Once scoring an astonishing 100 points in a game, Chamberlain was an almost unstoppable scoring threat for the Philadelphia 76ers and later the Los Angeles Lakers. Among the other N.B.A. greats of the 1960’s were Jerry West, Elgin Baylor, and Oscar Robertson.

1970’s The decade of the 1970’s marked a period of expansion, realignment, and competitive parity for the N.B.A. In 1970 the league expanded from 14 teams in two divisions to 17 teams in four divisions (two divisions each in Eastern and Western conferences). Then in 1976, with the merger of former ABA franchises, the total increased to 22. With growth came a new balance of power. The Celtic dynasty still thrived, winning championships in 1974 and 1976, but no team won consecutive N.B.A. crowns through the course of the decade. The New York Knicks were the only other team to capture two titles (1970 and 1973).

Center Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was the preeminent player of the decade, earning league M.V.P. honors six times; he would go on to become the leading scorer in N.B.A. history, retiring with 38,387 points in 1989. Other Hall of Famers from the 1970’s included Bill Walton, Julius “Dr. J” Erving, Willis Reed, Walt Frazier, Rick Barry, Nate “Tiny” Archibald, Dave Cowens, Pete Maravich, Calvin Murphy, and Bob McAdoo.

1980’s Although the N.B.A. continued its expansion in the 1980’s, reaching 27 teams by the 1989–90 season, the league faced declining game attendance and television ratings as the decade commenced. At least two factors contributed to a rebound in fan interest by mid-decade. One was the adoption of the three-point field goal before the 1979-80 season, which added an exciting dimension to the game. More important, perhaps, was the compelling rivalry that developed between the Los Angeles Lakers, led by Magic Johnson and Abdul-Jabbar, and the Boston Celtics, with Larry Bird. The Lakers won five championships during the 1980’s, the Celtics three. Johnson and Bird each captured three M.V.P. awards. Marquee players of the decade also included Erving and Moses Malone of the Philadelphia 76ers (champions in 1983), Isiah Thomas of the Detroit Pistons (champions in 1989 and 1990), Dominique Wilkins of the Atlanta Hawks, and a young Michael Jordan.

1990’s–Present By 1991, a century after its birth, basketball had attained a following that James Naismith could hardly have imagined. The professional game was an entertainment and merchandising industry. Standout players hailed from far-flung parts of the globe.

No individual better symbolized the success of professional basketball than Michael Jordan, an international

media celebrity, endorser of consumer products, millionaire many times over, and perhaps the sport’s greatest-ever player. The 6’6” Jordan, a shooting guard, carried the Chicago Bulls to six N.B.A. championships during the 1990’s, won the league scoring title 10 times, and was named M.V.P. five times. As Jordan’s career waned, younger stars—Shaquille O’Neal and Kobe Bryant—restored the Lakers to preeminence with three consecutive league crowns (2000–02).

The 21st century promised increasing globalization at virtual every level of play. Already N.B.A. rosters were filled with talented foreign players. Olympic and international amateur tournaments were closely contested. And Naismith’s game was being played in schools and playgrounds around the world.

In 2007, referee Tim Donaghy, under pressure from an FBI investigation, resigned and admitted his role in a betting scandal. Donaghy bet on the NBA over a two-year period, including games he officiated, and admitted to affecting the point spread. Recently, Lakers vs. Celtics, the league’s most historic matchup, had some luster restored as the teams met for the championship two times over a three-year period, with each franchise winning one title. Today in the NBA, the current trend is for marquee players to leave their small market teams in favor of the exposure and glamour associated with the large markets such as Chicago, New York, and Miami. This movement coupled with mis-management caused 17 of the 31 franchises to lose money in 2010.

In 2004 the Charlotte Bobcats joined the league (Charlotte’s earlier franchise, the Hornets, had moved to New Orleans in 2002), bringing the N.B.A. total to 30 teams. In 2008, the Seattle Supersonics franchise moved, changing their name to the Oklahoma City Thunder. There are N.B.A. teams in the United States and Canada, organized in two conferences (Eastern and Western), with three divisions in each. The season runs from October to June, with each team playing 82 regular-season games. The top 16 teams compete in four rounds of post-season playoffs, culminating in a best-of-seven championship series.

The current collective bargaining agreement expires at the end of the 2011 season and the owners hope to install a hard salary cap in the new agreement, helping to offset their losses. This proposal has been met with harsh resistance from the players and the two sides remain far apart. At this point a lockout is likely and there is a strong possibility the entire 2011-2012 will be lost.

Women’s Professional Basketball The development of women’s basketball at the college level and in the summer Olympics prompted the creation of two women’s leagues in the late 1990’s. The American Basketball League (A.B.L.) began operations in 1996 and was followed a year later by the W.N.B.A., a women’s league operated under the auspices of the N.B.A.. The W.N.B.A.’s marketing clout proved to be a decisive edge, and the ABL folded in 1999. The W.N.B.A. plays a spring/summer schedule from May through August that fits in well with the N.B.A. off-season. In the 2010 season, the W.N.B.A. had 10 teams divided between two conferences.

assist a pass that directly leads to a field goal by a teammate. Assists are an individual statistic.

blocked shot when a defensive player interferes with an opponent’s shot attempt by swatting or tipping the ball out of its desired trajectory.

double-dribble a violation in which a player dribbles the ball with two hands or stops dribbling and then resumes; the ball is awarded to the opposing team.

dribbling repetitive bouncing of the ball with one hand, while the player is in motion or standing still.

field goal a successful shot at the basket during the normal course of play; generally worth two points, or three points if shot from beyond a designated distance (the three-point line).

foul an infraction for improper physical play that is determined by the game officials. There are several types of fouls, including reaching in, blocking, charging, and over the back, among others. If a player commits six fouls in the course of the game, he is said to have fouled out, and must leave the court for the remainder of the contest. If a foul is committed on an offensive player in the act of shooting, the shooter is normally entitled to two foul shots, the exceptions being a single foul shot if the player’s original attempt was successful, or three foul shots if the shooter was fouled beyond the three-point line.

foul lane the painted area under the basket, bordered by the end line and the foul line; players must stand outside the area during foul shots and may not spend more than three consecutive seconds inside it during active play.

foul shot an uncontested attempt at the basket, taken from the foul line at a distance of 15 feet; one or two shots may be awarded for a personal foul (three if a player is fouled while attempting a three-point shot).

free throw another name for a foul shot.

goaltending when a defensive player touches a shot attempt after the ball has reached the height of its arc. As a result of a goaltending infraction, the shooting team is awarded the value of the shot attempt. Goaltending is also called when a player slaps the backboard or if the ball is touched directly above the goal, even by an offensive player.

jump ball method of putting the ball into play in which a referee tosses the ball in the air and two opposing players attempt to tap it to a teammate and gain possession.

man-to-man defense a strategy in which each defensive player is responsible for guarding a single offensive opponent.

officials in the N.B.A. there are three officials who enforce the rules of the game.

position the role performed by a player. Each team has five players on the court at any time, and any combination may be employed based on the game situation. Standard starting lineups include two guards, two forwards, and a center. Each of these is occasionally referred to by a number one through five that indicates the player’s role.

point guard (1) the primary ballhandler on offense. The point guard brings the ball up the court and seeks to pass the ball to other players for scoring opportunities. Their most important statistic is assists, though good shooting is also helpful. Quickness, vision, and passing ability, not height, are premium requisites.

shooting guard (2) along with the small forward, one of the primary scoring positions. The shooting guard’s job is to score points, either by jump shots or by driving to the basket. Usually taller than point guards, but still quick and good shooters.

small forward (3) another of the main scoring positions, slightly taller than the shooting guard, but equally capable of scoring from inside or outside. A player who combines speed and agility with some size.

power forward (4) a player who is a main scoring threat close to the basket, and concentrates on rebounding on the defensive and offensive ends of the floor. These players are tall and strong.

center (5) the tallest players on the court. Primary duty is on defense and rebounding, and most scoring is accomplished near the basket. A dominant center displays an uncommon mix of size, agility, and skill.

rebound recovering the ball after a missed shot. Also an individual statistic.

roster a list of all of the players on a team. N.B.A. teams have 12 players.

shot clock the device that tracks the time the offensive team has to attempt a shot. This 24-second period commences with the offense’s gaining possession of the ball. The clock is reset by such things as offensive rebounds, among others. If the offense does not shoot the ball before the 24 seconds elapses, the team suffers a shot clock violation, and the defending team takes possession.

steal when a defender intercepts or grabs the ball from the opposing team; a defensive statistic.

technical foul a violation called for a procedural violation or, at the discretion of the referee, misconduct; penalized by one foul shot and possession of the ball for the nonof-fending team.

three-point play a two-point field goal followed by a successful foul shot; made possible by the commission of a defensive foul as the offensive player is making a successful field goal attempt.

three-point shot a field goal worth three points because the shooter released the ball from behind the three-point line.

traveling a violation in which a player advances the ball by taking three steps without dribbling; possession is awarded to the opposing team; also known as walking.

turnover when the offensive team loses possession of the ball through a variety of methods, including passing the ball out of bounds, traveling, or double dribbling; a negative statistic, as a team that commits many turnovers will attempt fewer shots.

zone defense a strategy in which each defensive player is assigned a specific area of the court and must guard any opponent who enters that area; the zone configuration may take any of several forms, such as a 2-1-2, 1-3-1, or 2-3. In the N.B.A., zone defenses were only recently permitted by the rules.

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame

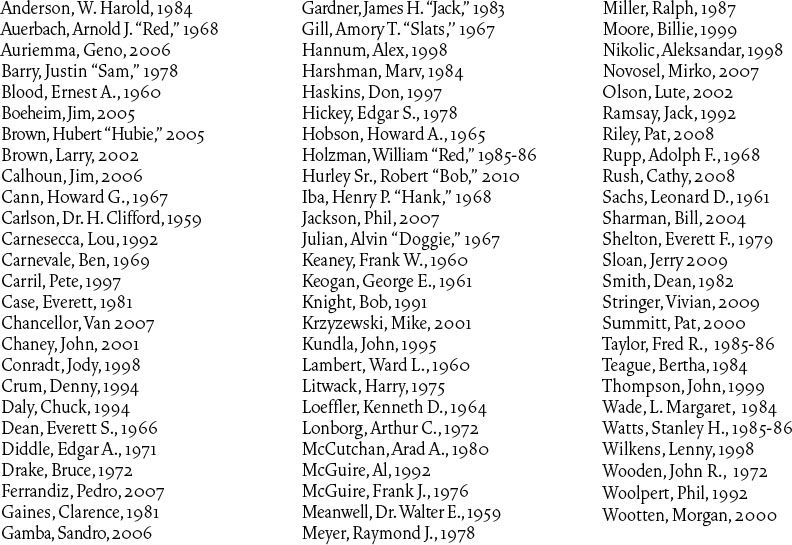

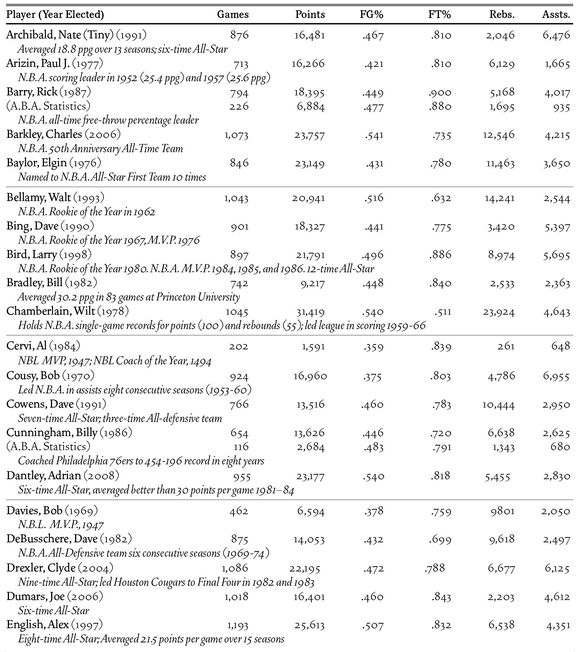

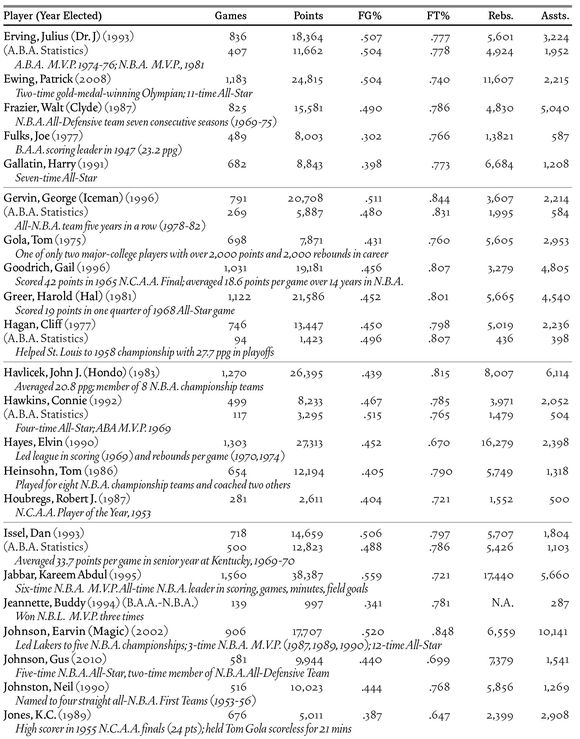

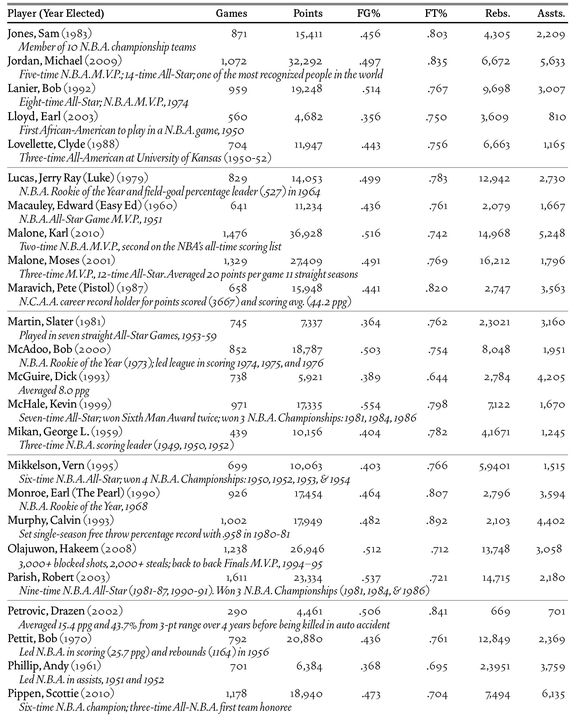

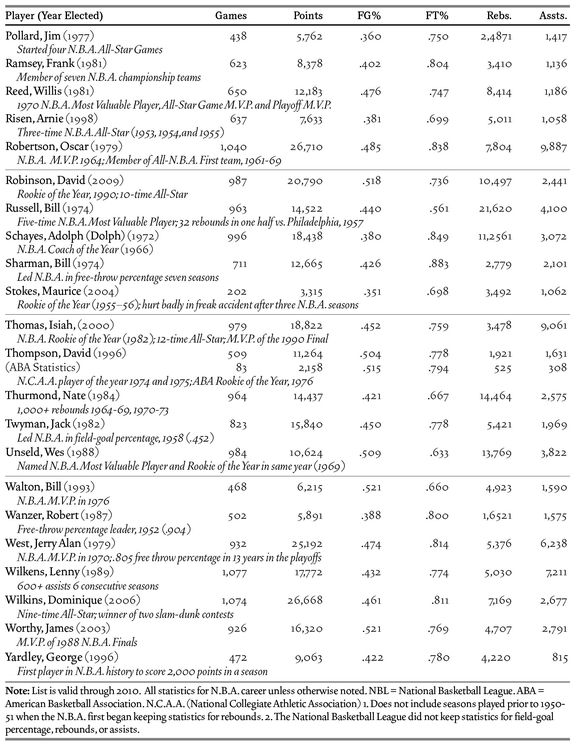

The Basketball Hall of Fame elected its first members (including Dr. James Naismith, the game’s originator) in 1959, but it did not have a physical home until February 17, 1968. In 1985 the Hall of Fame moved to larger quarters in Springfield, Mass. The Basketball Hall of Fame includes players from all basketball levels, including college, women’s, and foreign leagues. Career statistics are given only for players who played some portion of their career in the N.B.A.

Hall of Fame Coaches