Football, or American football, as it is known in the rest of the world, evolved from soccer and rugby in the late 19th century. On November 6, 1869, Rutgers and Princeton played a soccer-like game that would eventually evolve into modern football. During the next seven years, rugby gained popularity at eastern colleges, while soccer fell from favor. In 1876 the rules of American football became different enough from rugby that they were codified. At that time, a field goal and a touchdown were each worth four points.

Since then, American football has continued to diverge from its international cousins. Today there are hundreds of rules that differentiate American football from the version played around the world, the most ironic being that very little of the American game uses the feet.

With periodic breaks in the action, football is uniquely suited for television. Football’s symbiotic relationship with television has fueled its rise to the most popular sport in the United States and one of the most popular forms of entertainment in the world.

Although football’s myriad rules have evolved substantially in the sport’s first century, the differences among the high school, college, and professional games are few. A football field, itself now commonly regarded in the United States as a unit of measurement, is 100 yards long, demarcated every five yards by white stripes that run the width of the field (160 feet). At either end of the 100 yards are 10-yardlong end zones. At the center of the rear boundary of each end zone is a U-shaped goalpost with a crossbar 10 feet high and two uprights 18 1/2 feet apart. The surface is grass or synthetic grass. The middle of the field is the 50-yard line; numbers decrease on either side of the center stripe until they reach the 0-yard line, or the goal line.

The object of the game is to move the football into the end zone (a touchdown), or to get close enough so as to kick the ball between the uprights (a field goal). A touchdown is worth six points and carries with it the right to attempt an extra point (kicking the ball between the uprights from the 2 1/2 yard line) or a two-point conversion (moving the ball across the goal line again from the 2 1/2 yard line). A field goal is always worth three points. The defense can score by pushing an offensive player backward into his own end zone. This uncommon method of scoring is called a safety, and is worth two points.

Each team has 11 players on the field at once. The offensive team tries to advance the ball, and the defensive team seeks to stop them by tackling the player with the ball before he can advance down the field. The offensive team has four chances (or downs) to advance the ball 10 yards (a first down). If they achieve this goal, they are rewarded with four more downs to advance another 10 yards. If they fail, they must give the ball to the other team. At any time, the offensive team has the option of punting (i.e. kicking) the ball to the defensive team. Most teams do this on fourth down when it seems unlikely that they will get a first down.

The defense may also take possession by catching a pass intended for an offensive player (an interception), or by picking up the ball after it has been dropped by an offensive player (a fumble). Any player on either team may pick up a fumbled football.

The game is played in four 15-minute quarters, with a break for halftime. The teams switch ends of the field between the first and second quarters and the third and fourth quarters. The game commences with one team kicking the ball to the other team (the kickoff). After every touchdown and field goal, the team that scores kicks off again. At the game’s conclusion, the team with the most points wins.

Positions

The quarterback is the player who runs the offense on the field. He signals the start of play and either hands the ball to a running back or he retreats several steps into a pocket formed by the offensive line and attempts to throw the ball to an eligible receiver. Alternatively, he can run with the

ball himself. Quarterbacks are usually tall with a strong arm.

The running backs carry the ball most frequently on running plays. Often divided into two roles: the fullback, a player who specializes in blocking, and the tailback or halfback, who will run the ball most often. These players normally align behind the quarterback and offensive line.

The primary duty of the wide receivers is to catch passes. They align outside—often 10 to 12 yards—the offensive line, and are almost always the swiftest players on the offense. They try to run well-designed pass routes or patterns to separate themselves from defenders.

The offensive line is a set of five players whose responsibility is to protect the quarterback and block defenders to clear lanes for the running backs. The center initiates each play by snapping the ball to the quarterback. The center is flanked by two players called guards, and outside the guards are two tackles.

The defensive team is divided into three different units. The defensive players on the line of scrimmage are known as the defensive line. They are often separated into nose tackles (who align directly over or near the offensive center), tackles, and ends.

Linebackers are a group of defenders who usually begin each play immediately behind the defensive linemen or outside the linemen on the line of scrimmage. They are responsible for stopping running plays, covering short pass routes, and rushing the quarterback.

The defensive backs, known collectively as the secondary, have the primary responsibility of preventing the offense from progressing by the pass. In standard situations, the secondary numbers four players: two cornerbacks, a strong safety, and a free safety. In likely passing plays, defenses may choose a package of players called the “nickel” (an extra defensive back) or even the “dime” (two extras) at the expense of linebackers or linemen.

Origins

American football originated in the second half of the 19th century, evolving out of the British games of soccer and rugby. During the 1870’s, teams played various versions of the game, the home squad often dictating the rules. Early contests included Princeton against Rutgers in 1871 and Princeton versus Yale in 1873. The student captain was in charge of the team on and off the field. At Yale, Walter Camp proved to be a brilliant captain and, after his graduation in 1881, he stayed in New Haven and continued to run the squad as the “graduate manager.”

Camp, often called the “Father of Football,” worked to codify the on-field rules and to institute daily practice routines and game strategies. Because, above all, he wanted his teams to win, sometimes he enlisted athletes who were paid for playing football at Yale. Yale’s rivals, as well as other schools taking up the game, also wanted to win, and soon many rosters featured “ringers” (non-students) and “tramp athletes” (ringers who sold their services to more than one school during a season and/or over a number of seasons).

By the 1890’s, football moved off-campus and grew in popularity with the sporting press and the general public. The annual Thanksgiving Day contests in New York City, usually featuring Yale and Princeton, attracted significant media attention and large crowds. From this popularity came the first football stadium at Harvard in 1903. Unfortunately the on-field game, featuring the “flying wedge” formation where the offensive team linked arms and tried to trample their opponents, resulted in many injuries and some deaths. In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt invited the college presidents of the major Ivy League schools to the White House and insisted that they change the rules to eliminate violent play. Later that year, representatives of 28 schools with football teams met in New York City and formed the group that evolved into the National Collegiate Athletic Association (N.C.A.A.). After 1906 the rules became more uniform and outlawed fighting and open brutality; the new rules also allowed a limited version of the forward pass but kept the rugby-sized ball. Fullback plunges into the line became the main offensive weapon.

Early Success

During the first two decades of the 20th century, college football increased in popularity in the Northeast, but even more so in the Midwest. The largest schools in the Midwest—Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Purdue, Chicago, and Northwestern—formed a conference (the forerunner of the Big Ten) in 1895, and these universities began to produce some of the best football

teams in the country. Directing the on-field game were the graduate managers, who at many schools had become full-time, well-paid coaches and athletic directors. The media promoted the teams and focused public attention on the most successful and famous coaches and the best players.

From 1899 to 1924, Amos Alonzo Stagg won seven Big Ten championships for the University of Chicago with his “Monsters of the Midway”; Glenn “Pop” Warner invented the single wing and, from 1907 to 1914, won at Carlisle Institute (where few of his players were college students); and Fielding Yost had great success at the University of Michigan during the first decades of the century. The greatest player of the era was the Native American athlete Jim Thorpe, who played at Carlisle from 1908 to 1911. College football—unlike other organized sports, notably major and minor league baseball—was open to all minority groups, including African-Americans. In the mid-1910’s Paul Robeson at Rutgers and Fritz Pollard at Brown were football stars, their schools amenable to their playing and attending as long as they helped their teams win.

The Roaring Twenties and Great Depression

In the 1920’s, a decade of economic prosperity, college football expanded dramatically. Many schools, particularly in urban areas and in the South and Southwest, started or enlarged their teams, while many of the established football powers built huge stadiums and began organizing student and alumni activities around the games, particularly the new phenomenon of Homecoming.

The sporting press loved the hoopla of college football, and national sportswriters such as Grantland Rice turned the era’s stars into national heroes. Before ever seeing him play, Rice called Harold “Red” Grange, an outstanding running back at the University of Illinois, “The Galloping Ghost of the Illini.” But Rice’s greatest creation was “The Four Horsemen of Notre Dame,” a swift but small backfield for the decade’s most popular team, the Fighting Irish of the University of Notre Dame. Their innovative and entrepreneurial coach, Knute Rockne, aided by the media, turned the teams of a small Catholic school in northern Indiana into a national phenomenon. The more games and championships that Rockne’s teams won, the greater their popularity among regular fans. The Fighting Irish also made college football fans of millions of people, particularly working-class Catholics who previously had no interest in football or college. A decade later, Warner Brothers made a saccharine movie about this team and its coach, Knute Rockne—All-American, with future president Ronald Reagan portraying Rockne’s greatest player, George Gipp.

The Great Depression of the 1930’s erased some small college football programs, but the big ones persevered and, thanks to the new medium of radio, became even more popular. Notre Dame, West Point, and the Naval Academy allowed free broadcasts of their games and developed huge national followings, but even the schools that charged the broadcasters reached large local and regional audiences. In the mid-1930’s tourism promoters in a number of warm weather cities started the Sugar, Cotton, and Orange Bowls (the Rose Bowl, the “GrandDaddy of the Bowls,” had begun in 1903). The bowl promoters invited the most successful teams to participate in this extra game that took place after the regular season. This system remains in place in the modern college game. Another continuing tradition is the Heisman Trophy. In 1934 the Downtown Athletic Club of New York City created the annual trophy to honor the year’s best college player. During these years, the Southeastern and Southwestern conferences, in an attempt to lure athletes from the football-rich high schools of the north, offered the first athletic scholarships.

In 1934 the rules committee of the coaches association shrank the size of the football, and the forward pass started to become a major offensive weapon, particularly in the Southwest Conference, featuring passers such as “Slinging” Sammy Baugh and Davey O’Brien of Texas Christian University. Yet, in the North, running backs and fierce linemen still dominated the game, producing national champions at the University of Minnesota under coach Bernie Bierman, a.k.a. “Hammer of the North,” and outstanding teams at Fordham University, led by their “Seven Blocks of Granite” line.

World War II and Its Aftermath

During World War II, many schools curtailed their football programs, but various armed forces training camps fielded teams to play the college squads still operating. In addition, through the cooperation of draft boards around the country, West Point and the Naval Academy produced the best teams of the war era. Coach Earl “Red” Blaik’s Black Knights of the Hudson, with Heisman Trophy winners Felix “Doc” Blanchard and Glenn Davis leading the running attack, captured national championships in 1944 and 1945.

After the war, college football exploded in popularity.

Hundreds of schools entered or re-entered the sport, and more than 50 new bowl games began. Atop this chaotic situation stood the traditional powers, particularly teams from Big Ten and Pacific Coast Conference universities. Cheating was rampant, with coaches often employing professional athletes and not pretending that their players were students. Ruthless buccaneers like Paul “Bear” Bryant emerged, winning at every stop—in Bryant’s case at Maryland, Kentucky, Texas A & M, and eventually his alma mater, Alabama. Among the great players of the era—Heisman winners and runners-up—were Notre Dame quarterback Johnny Lujack and end Leon Hart; Southern Methodist running backs Doak Walker and Kyle Rote; Georgia’s Charley Trippi; and North Carolina’s Charlie “Choo-Choo” Justice.

In the 1950’s, for the first time, the N.C.A.A. permitted all of its members to award athletic scholarships, bringing them in line with the conferences already allowing them. However, the Ivy League schools, terming athletic scholarships as pay-for-play, refused to grant them and dropped out of big-time football. In 1952 tailback Dick Kazmaier of Princeton was the last Heisman Trophy winner from the league that had invented American college football.

In this decade, the N.C.A.A. also gained control of all televising of college football games and parceled them out to schools across the country—but did not allow the most popular teams, like Notre Dame, to appear more than a few times a season. Coach Bud Wilkinson’s Oklahoma Sooners dominated their conference, but Big Ten teams, notably coach Woody Hayes’s Ohio State Buckeyes and Clarence “Biggie” Munn’s Michigan State Spartans challenged Oklahoma for the top spot in the national ranking. Ohio State players Vic Janowicz and Howard “Hopalong” Cassidy won Heismans, as did Billy Vessels of Oklahoma. In addition, many black players entered big-time college football at this time; because southern and southwestern schools still excluded them, Big Ten universities were able to bring many excellent African-American players north to suit up for their teams.

The Full Integration of College Football

In 1961 Ernie Davis of Syracuse was the first black athlete to win the Heisman. A few years before, the great Jim Brown of Syracuse had finished far from the top spot because of the prejudiced voting of southern sportswriters. In the 1960’s, as civil rights issues became more important politically, so did black athletes at major schools: the University of Southern California won championships with Mike Garrett and O.J. Simpson (both Heisman winners). At the end of the decade, schools below the Mason-Dixon Line began to recruit black players—Jerry Levias at Southern Methodist was the first African-American to play in the Southwest Conference. Black athletes accelerated the integration of many colleges in the South and Southwest and, equally important, helped the fans of those teams accept integration. For most football fans, winning trumped racism, and if black players could bring championships, the fans wanted them on their teams. “Bear” Bryant of Alabama, after losing a game to a U.S.C. squad led by black running back Sam Cunningham, integrated the Crimson Tide in the early 1970’s, and Alabama fans cheered as the team added more national championships to its list.

In this era, TV coverage of intercollegiate football changed. Roone Arledge began producing telecasts for ABC-TV, and he portrayed college football as a spectacle, not just a contest on a field. He employed many more cameras than had been used before, and his crews frequently focused on coaches and cheerleadeers on the sidelines, fans in the crowd, as well the on-field action. Arledge wanted the TV audience to stay tuned to the game—and the ads—whether the score was lopsided or not; he wanted the spectacle to transcend the sport. His approach came to dominate television coverage of college sports, as did the increasing intrusion of commercial sponsors.

The Final Decades of the Century

In 1973 the N.C.A.A. changed athletic scholarships from a guaranteed four-year grant to a one-year contract renewed at the behest of the athlete’s coach, in effect making a football player an employee of his athletic department and under the strict control of his coach. The new system rewarded martinets like Ohio State’s Woody Hayes, who put his players through long, grueling practices and demanded absolute obedience. In the 1970’s his Buckeyes won Big Ten titles and played in Rose Bowls, and his running back Archie Griffin garnered two Heisman Trophies (and remains the only multiple Heisman winner). But Hayes’s career ended in 1978 when he ran onto the field during a bowl game between Ohio State and Clemson and punched a player on the opposing squad. Other outstanding Heisman winners of the 1970’s and their national championship teams were Tony Dorsett at Pitt, Johnny Rodgers at Nebraska, and Charles White at U.S.C.

In 1976 61 of the major football schools formed the College Football Association. Dissatisfied with the

N.C.A.A.’s control of the sport, they sought more autonomy over and revenue from their football programs. Two C.F.A. schools, the universities of Georgia and Oklahoma, challenged the N.C.A.A.’s monopoly on telecasts of college football games in court. In a series of verdicts, ending with an almost unanimous 1984 Supreme Court decision, the C.F.A. schools prevailed, and the N.C.A.A. lost control of televising college football. As a result, many national and local networks began broadcasting the games, and many schools, seeking better payouts, moved the scheduling of contests from the traditional Saturday afternoon spot to night games, then games on other days and nights of the week.

In the 1980’s the University of Miami Hurricanes, with such excellent quarterbacks as Bernie Kosar and Vinny Testaverde, rose to the top of the polls, and won national titles in 1983, 1987, and 1989. Other excellent teams of the decade were coach Barry Switzer’s Oklahoma Sooners and coach Joe Paterno’s Penn State Nittany Lions. The articulate Paterno, a graduate of Brown University, was often pointed to as an exemplary coach; he accepted the acclaim and also criticized the increasing corruption in his sport. Many critics and two major reform groups, the Knight Commission and the N.C.A.A. Presidents’ Commission, suggested reforms; however, they could never convince powerful coaches and athletic directors to agree to any meaningful changes in the college sports system.

The Contemporary Era

In the 1990’s the on-field game came to resemble a version of professional football, and an increasing number of coaches shuttled back and forth between college and N.F.L. teams. Many players considered themselves in minor league training for the N.F.L. and, as a result, the graduation rates of the best teams were often very low. Coach Bobby Bowden’s Florida State Seminoles won conference titles, bowl games, and two national championships in the 1990’s, and also featured many players who did not graduate and some who acquired criminal records while in college.

At the end of the century, the division between the have and have-not teams in college football increased, and the rich schools and conferences took the lion’s share of revenue from television and the bowl games. The haves codified their status when they endorsed the Bowl Championship Series (B.C.S.) in 1992 and convinced the N.C.A.A. to give them semi-autonomous status a few years later. This situation contributed to the demise of the Southwest Conference in 1996 and major shifts in other leagues. In 2003 the Big East football conference, only formed in 1990, lost two important members, Miami and Virginia Tech, to the Atlantic Coast Conference, and this started a domino effect with stronger conferences considering raids on weaker ones to replace departed schools.

These changes had a profound effect on college football as 23 teams changed conferences. Even more defections occurred over the next few years as Colorado and Nebraska left the Big 12 for the Pac-10 and Big Ten respectively. Consequently, the Big-12 now has 10 teams while the Big Ten and Pac-10 have 12. Proponents of a playoff system have increased in recent years as several small conference teams have gone undefeated, being left out of the title game in favor of one- or two-loss teams from major conferences by the B.C.S. computers. This has led to calls for a college football playoff system from Congress and even the White House. Because of the large amount of money tied up in the B.C.S. system, it is highly unlikely that any changes will take place in the near future. In June 2011, the B.C.S. stripped U.S.C. of its 2004 National Championship, after the N.C.A.A. ruled that Reggie Bush had improperly accepted benefits, making him ineligible to play and thus voiding their title.

One thing that seems not to change is the coach at Penn State. In 2011, Joe Paterno will be entering his 62nd season on the coaching staff and 45th as head coach of the Nittany Lions. Because power and greed seem to motivate the men and women running the major conferences and schools, many more changes in college football likely will occur in the first decades of the 21st century. And the game will become increasingly commercial and professional, with more coaches earning more than $1 million a year, and their players detached from regular student life. Yet fans will continue to love college football, attend games and watch them on TV, and the sport will remain an important part of their lives. No other higher education system in the world has produced such an unusual institution as American intercollegiate football.

From its roots in rugby and soccer, American football began its own history in 1876, with the first set of rules. By 1902 the sport had already seen its first professional player (William “Pudge” Heffelfinger, in 1892), its first all professional team (the Allegheny Athletic Association, in 1896), and its first night game (1902, Elmira, N.Y.). But interest in the pro game was largely limited to the Great Lakes states.

Backward passes, or laterals, were always a part of the game, remnants of the sport’s rugby ancestry. It wasn’t until 1906 that the forward pass was legalized. However, until 1933, the forward pass had to be thrown from five yards behind the line of scrimmage. Other notable rule changes over time included reducing the value of a field goal from four points to three. The value of a touchdown was raised from four points to five in 1898 and raised again to six points in 1909. Though there have been literally hundreds of changes to the rules and equipment since then, today’s game has much in common with its ancestor.

1920’s and 1930’s

The American Professional Football League was formed in 1920, and adopted a constitution a year later for its 22 franchises. In 1922 the association changed its name to the National Football League. Two extant N.F.L. franchises predate the league’s existence: the Arizona (formerly St. Louis, formerly Chicago) Cardinals (1899), and the Green Bay Packers (1919). The number of franchises fluctuated as high as 23 clubs in 1925 and as low as eight teams in 1932, as the Depression took its toll on the league.

The sport first attracted national attention in 1925, when All-America quarterback Red Grange, from the University of Illinois, signed a contract with the Chicago Bears. A then-record crowd of 36,000 people watched the “Galloping Ghost” play his first pro game at Wrigley Field. The Bears then went on a barnstorming tour across the country that brought crowds of 73,000 to the Polo Grounds for a game against the New York Giants and 75,000 to the Los Angeles Coliseum for an exhibition against the L.A. Tigers.

The N.F.L. changed the forward pass rule in 1933, so that the ball could be thrown from anywhere behind the line of scrimmage. The rule change increased the importance of the quarterback position, giving rise to passers like “Slingin’” Sammy Baugh. In 1935 the N.F.L. adopted a draft, with teams choosing players from college’s game in inverse order of finish; a year later, the Philadelphia Eagles chose Heisman Trophy winner Jay Berwanger, a University of Chicago running back, with the first pick.

N.F.L. attendance topped 1 million for the first time in 1939. Also that year, the league’s first game was televised, a game between the Eagles and the Brooklyn Dodgers. Fewer than one thousand people owned television sets at the time, but this paved the way for football to become a fixture in American living rooms.

1940’s and 1950’s

World War II decimated several franchises, forcing some teams to merge with each other for a season or longer. In 1943, the era of specialization began when the league adopted free substitution. Amended in 1946, it was restored in 1950, allowing players to play only offense or defense, and to go out of the game for a play or longer and then return. The league also approved a 10-game schedule and made helmets mandatory. Five years later, the Los Angeles Rams painted horns on their helmets, becoming the first team to add emblems to their headgear.

The rival All-America Football Conference started play in 1946 with eight teams, three of which (Cleveland Browns, Baltimore Colts, and San Francisco 49ers) were welcomed into the N.F.L. in 1949. This began the N.F.L.’s hegemony over competitive leagues by appropriating their strongest assets. The A.A.F.C. folded in 1950, and its players were allocated to N.F.L. franchises through a special draft.

That same year, the Los Angeles Rams, and later the Washington Redskins, negotiated deals to have all their games televised. In 1951 the Rams televised only road games in an attempt to increase attendance. Later that year, the DuMont Network paid $75,000 to televise the N.F.L. Championship game coast to coast. NBC paid $100,000 for the 1955 title game, and in 1956 CBS began broadcasting regular season games on Sunday afternoons.

On December 28, 1958, the Baltimore Colts and New York Giants played for the N.F.L. title in what many still deem the greatest football game ever played. The game went into overtime (a first for the title game) before Colts fullback Alan Ameche scored the winning touchdown.

1960’s and 1970’s

The N.F.L. was at a crossroads in 1960. After longtime Commissioner Bert Bell died of a heart attack, league owners could not agree on a successor. Finally, on the 23rd ballot, they settled on Rams general manager Pete Rozelle. Over the next three decades, Rozelle would guide the

league through unprecedented growth, surpassing even baseball, the national pastime, as America’s favorite sport.

The N.F.L. faced competition from another upstart league, the American Football League, which was scheduled to launch in the fall of 1960. But the N.F.L. eviscerated its would-be rival, awarding N.F.L. franchises to Minnesota (which then withdrew from the A.F.L.) and to Dallas (home of A.F.L. president Lamar Hunt’s Dallas Texans).

Even though the A.F.L.’s two-year-long antitrust suit against the N.F.L. failed in 1962, the new league’s high-scoring offenses attracted fans and television money. ABC signed a five-year deal in 1960, and NBC took over A.F.L. broadcasts in 1965 for $36 million over the next five years. In 1965 the A.F.L.’s New York Jets signed Alabama quarterback Joe Namath to a three-year, $427,000 deal, a record salary for any football player. The deal sparked a bidding war between the two leagues as they spent a combined $7 million on their 1966 draft choices.

The champions of each league squared off in the first A.F.L.-N.F.L. World Championship game in 1967. The contest wouldn’t be dubbed “Super Bowl” for another year, and the game wasn’t a sellout. In the first title game, the Green Bay Packers defeated the Kansas City Chiefs 35-10. Bart Starr led the Packers to a second championship a year later over the Oakland Raiders. In 1969 Namath roiled the football world again by predicting the Jets would defeat the heavily favored Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III. His prediction was correct, and the shocking upset brought credibility to the younger league.

Unable to vanquish its newest competitor, the N.F.L. consumed it in a merger of the two leagues. In 1970 Baltimore, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh joined the 10 A.F.L. teams to form the American Football Conference. The remaining 13 teams made up the National Football Conference. From 1972 to 1980, the former A.F.L. teams dominated. The Miami Dolphins completed football’s only undefeated season in 1972 and repeated as champions in 1973. They were succeeded by the Pittsburgh Steelers, whose “Steel Curtain” defense won four championships (1974, 1975, 1978, and 1979), and the Oakland Raiders (1976 and 1980).

The N.F.L.’s relationship with television changed forever because of what came to be known as the “Heidi” game. On November 17, 1968, NBC cut away in the last minute of the Jets-Raiders game so the beloved children’s movie could start on time. The Raiders scored two touchdowns in the last 42 seconds for a come-from-behind 43–32 win. Since then, any time a football game has run past its scheduled ending time, the networks have delayed the programming that follows it until the contest’s completion.

Football also conquered prime-time television with the advent of Monday Night Football in 1970. It would become the longest-running prime-time series in the network’s history. Meanwhile, the Super Bowl began its rise from curiosity to the most-watched event in world history. By 1971 the TV audience of 24 million homes was the largest ever for a one-day sports event. Two years later, a record 75 million people tuned in. In 1978 the Super Bowl audience topped 102 million.

Another rival league, the World Football League, started operation in 1974, with franchises concentrated in the Sun Belt and Canada. The W.F.L. scored a coup by signing three Miami Dolphins stars to lucrative contracts, but the league folded after only two seasons.

The N.F.L. extended its season from 14 to 16 games in 1978 and added a second wildcard team in each conference to the playoff structure. The two wildcard teams played each other, with the winner advancing to the eight-team playoffs. Additional rule changes outlawed the head slap and allowed defenders to make contact with receivers only once; wide receivers were prohibited from blocking a defender in the back.

1980’s to the Present

In 1982 an astounding 73 percent of American homes tuned in to the Super Bowl, making it the highest-rated sports event in history. The 1986 Super Bowl drew a record 127 million viewers, a greater overall number of people, but a slightly lower percentage. Although competition from more networks and channels has fractured the TV audience since then, the Super Bowl is routinely the most-watched television program of the year.

Other off-the-field developments played pivotal roles in the N.F.L.’s recent history. Players’ strikes in 1982 and 1987 shortened those seasons to nine and 15 games respectively; in 1987 the owners hired replacement players for three games before the regulars returned. Those strikes resulted in increased free agency for players, but allowed clubs some leeway to retain “franchise players.”

The new labor agreements maintained the N.F.L.’s system of revenue-sharing, ballyhooed as the saving grace for small market teams like Green Bay and Cincinnati. But they did nothing to stop the trend of owners hijacking franchises and moving them to the city with the most favorable deal. The Raiders moved from Oakland to Los

Angeles in 1982, and returned to Oakland in 1995. Los Angeles, the nation’s second-largest media market, was left without a team, as that same year, the Rams departed for St. Louis, which had been ditched in 1987 by the Cardinals, who had fled to Phoenix.

Baltimore Colts owner Robert Irsay surreptitiously packed his team into moving vans in the middle of the night of January 14, 1984, and opened shop the next day in Indianapolis. Recognizing Baltimore’s hunger for Sunday afternoon entertainment, Cleveland Browns owner Art Modell moved his team there in 1996 and renamed it the Ravens. The N.F.L. responded by awarding an expansion franchise, also called the Browns, to Cleveland to begin play in 1999. The Houston Oilers relocated to Nashville in 1998, and changed their name to the Titans the year after. In 2002 jilted Houston received an expansion franchise, bringing the total number of N.F.L. teams to 32.

To accommodate all the moving and expanding, the league realigned each conference from three divisions to four in 2002, preserving traditional rivalries while imposing some geographic order. Because the number of division champions increased from six to eight, the number of playoff wildcard teams, which had been increased to six in 1990, was reduced to four, keeping the total number of playoff teams at 12.

Two other rival leagues came and went quickly: the U.S.F.L., which won an antitrust suit against the N.F.L. in 1986, but was awarded damages of only $1, and soon went out of business; and the X.F.L., a joint venture of NBC and pro wrestling impresario Vince McMahon. The first week of the 2001 X.F.L. season drew large crowds and ratings, but the poor quality of play could not sustain that level of interest, and the league folded after its first year.

Meanwhile, the N.F.L. spread its influence across the globe. After exhibition games in London (1986), Tokyo (1989), Berlin (1990), and Montreal (1990) drew sizable crowds, the league launched the World League of American Football in 1990, scuttled it in 1993, reintroduced it in 1995 with six European franchises, and renamed it N.F.L. Europe in 1998.

All the while, the television money kept rolling in, with networks paying record sums for broadcast rights. The latest contracts were worth $20.4 billion dollars, with the rights for Sunday’s games going to Fox, CBS, and NBC (Sunday Night Football) through 2011 and Monday Night Football making its home at ESPN until 2013. Looking to squeeze even more money out of its loyal fans, the N.F.L Network was created in 2006. In order to make their venture more attractive, the league added eight Thursday or Saturday night games to their lineup starting in Week 10. Due to problems with cable distribution and the limited reach of the network, many fans were left unable to see the games, caught in a struggle for money and power between giant corporations.

There were also developments on the field. Miami’s Dan Marino rewrote the record book for quarterbacks, only to have it rewritten again a few years down the line by Brett Favre, the highlight of which was his 297 consecutive regular season games started streak. San Francisco’s Jerry Rice became the all-time leader in receptions and receiving yards in 1995, then continued to play past his 40th birthday for the Raiders. Chicago Bear running back Walter Payton broke Jim Brown’s record for career rushing yards in 1987, and Emmitt Smith of the Cowboys surpassed Payton’s record in 2002.

The NFC returned to dominance, winning 13 straight Super Bowls from the 1984 to the 1996 seasons, most of them in blowouts. Quarterback Joe Montana orchestrated Bill Walsh’s pass-first West Coast offense to perfection to lead the San Francisco 49ers to four Super Bowls.

The N.F.L.’s desire for parity has kept more teams in the playoff hunt late into the season, but critics say it has led to an overall mediocrity. A total of 14 different teams appeared in the 2000–2007 Super Bowls, with six different winners.

Stung by a series of off-the-field violent incidents including shootings, DUI manslaughter and the death of a few players, new commissioner Roger Goodell has made his mark by being a strong disciplinarian. Looking to remove some tarnish from the league, Mr. Goodell has handed out yearlong suspensions on more than one occasion. During the 2010 season the N.F.L. started cracking down on violent hits, handing out hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of fines, although no players were suspended. This action has come under fire from many current and former players who feel the commissioners office is being overprotective of its marquee offensive stars, thus making the game less exciting. However, the latest medical research supports the N.F.L.’s view, showing a strong correlation between concussions in N.F.L. players and future bouts of depression and Alzheimer’s disease.

After the 2010 season, the collective bargaining agreement between the league owners and the N.F.L. Player’s Association was allowed to expire. The owners claimed they were losing money and asked for a reduction in player salaries. The players demanded the teams open their

books and prove this was the case or they would accept no such concessions. The N.F.L. owners refused and set March 3rd as the date they would lockout the players if no deal had been reached. Talks soon broke down and the players union voted to decertify and the owners officially began the lockout. On April 25, 2011, U.S. District Court Judge Susan Nelson sided with the players and invalidated the lockout. This ruling caught the owners off-guard as they were unprepared for the return of their players. Chaos reigned for days as players across the league showed up for work, only to be denied entry to weight and locker rooms, with some players locked out of the facilities entirely. Four days after the ruling the first round of the NFL draft was held. Due to the current labor situation teams were unable to trade players during the draft and couldn’t contact undrafted players after the draft had finished. On April 29th the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals granted the league a temporary stay of Judge Nelson’s ruling, and on May 16th a permanent stay was granted. The N.F.L. owners and players signed a new 10-year agreement on July 25th, salvaging the 2011 season.

Herb Adderley (1980) CB, Packers, Cowboys.

Troy Aikman (2006) QB, Cowboys.

George Allen (2002) Coach, Rams, Redskins.

Marcus Allen (2003) RB, Raiders, Chiefs.

Lance Alworth (1978) WR, Chargers, Cowboys.

Doug Atkins (1982) DE, Browns, Bears, Saints.

Morris (Red) Badgro (1981) E, Yankees, Giants, Dodgers.

Lem Barney (1992) CB, Lions.

Cliff Battles (1968) RB, QB, Braves, Redskins.

Sammy Baugh (1963) QB, Redskins.

Chuck Bednarik (1967) C, LB, Eagles.

Bert Bell (1963 Charter) Commissioner, N.F.L. Founder/coach, Eagles, Steelers.

Bobby Bell (1983) LB, DE, Chiefs.

Raymond Berry (1973) E, Colts.

Elvin Bethea (2003) DE, Oilers.

Charles W. Bidwill, Sr. (1967) Owner/president, Cardinals.

Fred Biletnikoff (1988) WR, Raiders.

George Blanda (1981) QB, PK, Bears, Colts, Oilers, Raiders.

Mel Blount (1989) CB, Steelers.

Terry Bradshaw (1989) QB, Steelers.

Bob Brown (2004) T, Eagles, Rams, Raiders.

Jim Brown (1971) FB, Browns.

Paul E. Brown (1967) Coach and GM, Browns, Bengals.

Roosevelt Brown (1975) OT, Giants.

Willie Brown (1984) CB, Broncos, Raiders.

Buck Buchanan (1990) DT, Chiefs.

Nick Buoniconti (2001) LB, Patriots, Dolphins.

Dick Butkus (1979) LB, Bears.

Earl Campbell (1991) RB, Oilers, Saints.

Tony Canadeo (1974) RB, Packers.

Joe Carr (1963) N.F.L. President.

Harry Carson (2006) LB, Giants.

Dave Casper (2002) TE, Raiders, Oilers, Vikings.

Guy Chamberlin (1965) E, Bulldogs, Staleys, Yellowjackets, Cardinals. Coach, Bulldogs, Yellowjackets, Cardinals.

Jack Christiansen (1970) DB, Spartans, Lions.

Earl (Dutch) Clark (1970) DB, Spartans, Lions, Rams.

George Connor (1975) OT, DT, LB, Bears.

Jimmy Conzelman (1964) QB, Staleys, Independents, Badgers, Panthers. Owner, Steamrollers, Cardinals.

Lou Creekmur, (1996) OL, Lions.

Larry Csonka (1987) RB, Dolphins, Giants.

Al Davis (1992) President, Owner, General Manager, Coach, Raiders. Commissioner, A.F.L.

Willie Davis (1981) DE, Browns, Packers.

Len Dawson (1987) QB, Steelers, Browns, Texans, Chiefs.

Fred Dean (2008) DE, Chargers, Raiders.

Joe DeLamielleure (2003) G, Bills, Browns.

Richard Dent (2011) DE, Bears, 49ers, Colts, Eagles.

Eric Dickerson (1999) RB, Rams, Colts, Raiders, Falcons.

Dan Dierdorf (1996) OT, Cardinals.

Mike Ditka (1988) TE, Bears, Eagles, Cowboys.

Art Donovan (1968) DT, Colts, Yankees, Texans.

Tony Dorsett (1994) RB, Cowboys, Broncos.

John (Paddy) Driscoll (1965) QB, Pros, Staleys, Cardinals, Bears.

Bill Dudley (1966) RB, Steelers, Lions, Redskins.

Albert Glen (Turk) Edwards (1969) OT, Braves, Redskins.

Carl Eller (2004) DE, Vikings, Seahawks.

John Elway (2004) QB, Broncos.

Weeb Ewbank (1978) Coach, Colts, Jets.

Marshall Faulk (2011) RB, Colts, Rams.

Tom Fears (1970) E, Rams.

Jim Finks (1995) President, Vikings, Bears, Saints.

Ray Flaherty (1976) Coach, Redskins, Yankees.

Len Ford (1976) DE, E, Dons, Browns, Packers.

Dan Fortmann (1965) G, Bears.

Dan Fouts (1993) QB, Chargers.

Benny Friedman (2005) QB, Bulldogs, Wolverines, Giants, Dodgers.

Frank Gatski (1985) C, Browns, Lions.

Bill George (1974) LB, Bears, Rams.

Joe Gibbs (1996) Coach, Chargers, Redskins. Frank Gifford (1977) RB, Giants.

Sid Gillman (1983) Coach, Rams, Chargers, Oilers. Otto Graham (1965) QB, Browns.

Harold (Red) Grange (1963 Charter) RB, Bears, Yankees. Bud Grant (1994) Coach, Vikings.

Darrell Green (2008) CB, Redskins.

(Mean) Joe Greene (1987) DT, Steelers.

Forrest Gregg (1977) OL, Packers, Cowboys.

Bob Griese (1990) QB, Dolphins.

Russ Grimm (2010) G, Redskins.

Lou Groza (1974) OT, PK, Browns.

Joe Guyon (1966) RB, Bulldogs, Indians, Independents, Cowboys, Giants.

George Halas (1963) Founder, Coach, player, Staleys. President, Coach, player, Bears.

Jack Ham (1988) LB, Steelers.

Dan Hampton (2002) DE/DT, Bears.

Chris Hanburger (2011) LB, Redskins.

John Hannah (1991) G, Patriots.

Franco Harris (1990) RB, Steelers, Seahawks.

Bob Hayes (2009) WR, Cowboys, 49ers.

Mike Haynes (1997) CB, Patriots, Raiders.

Ed Healey (1964) OT, Independents, Bears.

Mel Hein (1963) C, Giants.

Ted Hendricks (1990) LB, Colts, Packers, Raiders.

Wilbur (Pete) Henry (1963) OT, Bulldogs, Giants, Maroons.

Arnie Herber (1966) QB, Packers, Giants.

Bill Hewitt (1971) E, Bears, Eagles.

Gene Hickerson (2007) G, Browns.

Clarke Hinkle (1964) RB, Packers.

Elroy (Crazylegs) Hirsch (1968) HB, E, Rockets, Rams.

Paul Hornung (1986) HB, Packers.

Ken Houston (1986) S, Oilers, Redskins.

Cal Hubbard (1963) OT, Giants, Packers, Pirates.

Sam Huff (1982) LB, Giants, Redskins.

Lamar Hunt (1972) Founder, AFL; Owner Texans, Chiefs.

Don Hutson (1963) E, Packers.

Michael Irvin (2007) WR, Cowboys.

Ricky Jackson (2010) LB, Saints, 49ers.

Jimmy Johnson (1994) CB, 49ers.

John Henry Johnson (1987) RB, 49ers, Lions, Steelers, Oilers.

Charlie Joiner (1996), WR, Oilers, Bengals, Chargers.

Deacon Jones (1980) DE, Rams, Chargers, Redskins.

Stan Jones (1991) G, DT, Bears, Redskins.

Henry Jordan (1995) DT, Packers.

Sonny Jurgensen (1983) QB, Eagles, Redskins.

Jim Kelly (2002) QB, Bills.

Leroy Kelly (1994) RB, Browns.

Walt Kiesling (1966) G, Eskimos, Maroons, Cardinals, Bears, Packers, Pirates. Coach, Pirates, Steelers.

Frank (Bruiser) Kinard (1971) OT, Dodgers, Yankees.

Paul Krause (1998) S, Vikings, Redskins.

Early (Curly) Lambeau (1963) Founder, Packers. Coach, Packers, Cardinals, Redskins.

Jack Lambert (1990) LB, Steelers.

Tom Landry (1990) Coach, Cowboys.

Dick (Night Train) Lane (1974) DB, Rams, Cardinals, Lions.

Jim Langer (1987) C, Dolphins, Vikings.

Willie Lanier (1986) LB, Chiefs.

Steve Largent (1995) WR, Seahawks.

Yale Lary (1979) DB, Lions.

Dante Lavelli (1975) E, Browns.

Bobby Layne (1967) QB, Bears, Bulldogs, Lions, Steelers.

Dick LeBeau (2010) CB, Lions.

Alphonse (Tuffy) Leemans (1978) RB, Giants.

Marv Levy (2001) Coach, Chiefs, Bills.

Bob Lilly (1980) DT, Cowboys.

Floyd Little (2010) RB, Broncos.

Larry Little (1993) G, Chargers, Dolphins.

James Lofton (2003) WR, Packers, Raiders, Bills, Rams.

Vince Lombardi (1971) Coach, GM, Packers, Redskins.

Howie Long (2000) DL, Raiders.

Ronnie Lott (2000) DB, 49ers, Raiders, Jets.

Sid Luckman (1965) QB, Bears.

William Roy (Link) Lyman (1964) T, Bulldogs, Yellowjackets, Bears.

Tom Mack (1999) OG, Rams.

John Mackey (1992) TE, Colts, Chargers.

John Madden (2006) Coach, Raiders.

Tim Mara (1963) Founder, President, Giants.

Wellington Mara (1997) Owner, Giants.

Gino Marchetti (1972) DE, Texans, Colts.

Dan Marino (2005) QB, Dolphins.

George Preston Marshall (1963) Founder, President, Braves (Redskins).

Bruce Matthews (2007) G/T/ C, Oilers, Titans.

Ollie Matson (1972) RB, Cardinals, Rams, Lions, Eagles.

Don Maynard (1987) WR, Giants, Titans, Jets, Cardinals.

George McAfee (1966) RB, Bears.

Mike McCormack (1984) OT, Yankees, Browns.

Tommy McDonald (1998) WR, Eagles, Cowboys, Rams.

Hugh McElhenny (1970) RB, 49ers Vikings, Giants, Lions.

John (Blood) McNally (1963) RB, Badgers, Eskimos, Maroons, Packers, Pirates, Packers.

Mike Michalske (1964) G, Yankees, Packers.

Wayne Millner (1968) E, Redskins. Coach, Eagles.

Bobby Mitchell (1983) WR/RB Browns, Redskins.

Ron Mix (1979) OT, Chargers, Raiders.

Art Monk (2008) WR, Redskins, Jets, Eagles.

Joe Montana (2000) QB, 49ers, Chiefs.

Warren Moon (2006) QB, Oilers, Vikings, Seahawks, Chiefs.

Lenny Moore (1975) WR, RB, Colts.

Marion Motley (1968) RB, Browns, Steelers.

Mike Munchak (2001) G, Oilers.

Anthony Muñoz (1998) T, Bengals.

George Musso (1982) OT, G, Bears.

Bronko Nagurski (1963) RB, Bears.

Joe Namath (1985) QB, Jets, Rams.

Earle (Greasy) Neale (1969) Coach, Eagles.

Ozzie Newsome (1999) TE, Browns.

Ernie Nevers (1963) RB, Eskimos, Cardinals.

Ray Nitschke (1978) LB, Packers.

Chuck Noll (1993) Coach, Steelers.

Leo Nomellini (1969) DT, 49ers.

Merlin Olsen (1982) DT, Rams.

Jim Otto (1980) C, Raiders.

Steve Owen (1966) T, Cowboys, Giants. Coach, Giants.

Alan Page (1988) DT, Vikings, Bears.

Clarence (Ace) Parker (1972) QB, Dodgers, Yankees.

Jim Parker (1973) OL, Colts.

Walter Payton (1993) RB, Bears.

Joe Perry (1969) RB, 49ers, Colts.

Pete Pihos (1970) E, Eagles.

Fritz Pollard (2005) HB, Coach, Pros/Indians, Badgers, Cadamounts, Steam Roller.

John Randle (2010) DT, Vikings, Seahawks.

Hugh (Shorty) Ray (1966) Supervisor of Officials.

Dan Reeves (1967) Owner, Rams.

Mel Renfro (1996), CB, Cowboys.

Jerry Rice (2010) WR, 49ers, Raiders, Seahawks.

Les Richter (2011) LB, Rams.

John Riggins (1992) RB, Jets, Redskins.

Jim Ringo (1981) C, Packers, Eagles.

Andy Robustelli (1971) DE, Rams, Giants.

Art Rooney (1964) Founder, President, Pirates, Steelers.

Dan Rooney (2000) President, Steelers.

Pete Rozelle (1985) Commissioner, N.F.L.

Bob St. Clair (1990) OT, 49ers.

Ed Sabol (2011) Founder of NFL Films.

Barry Sanders (2004) RB, Lions.

Charlie Sanders (2007) TE, Lions.

Deion Sanders (2011) CB, KR, PR, Falcons, 49ers, Cowboys, Redskins, Ravens.

Gale Sayers (1977) RB, Bears.

Joe Schmidt (1973) LB, Lions. Coach, Lions.

Tex Schramm (1991) GM, Cowboys.

Lee Roy Selmon (1995) DE, Buccaneers.

Shannon Sharpe (2011) TE, Broncos, Ravens.

Billy Shaw (1999) OG, Bills.

Art Shell (1989) OT, Raiders.

Don Shula (1997) Coach, Colts, Dolphins.

O.J. Simpson (1985) RB, Bills, 49ers.

Mike Singletary (1998) LB, Bears.

Jackie Slater (2001) OT, Rams.

Bruce Smith (2009) DE, Bills, Redskins.

Jackie Smith (1994) TE, Cardinals, Cowboys.

John Stallworth (2002) WR, Steelers.

Bart Starr (1977) QB, Packers.

Roger Staubach, (1985) QB, Cowboys.

Ernie Stautner (1969) DT, Steelers.

Jan Stenerud (1991) PK, Chiefs, Packers, Vikings.

Dwight Stephenson (1998) C, Dolphins.

Hank Stram (2003) Coach, Texans, Chiefs, Saints.

Ken Strong (1967) RB, Stapletons, Giants, Yankees.

Joe Stydahar (1967) OT, Bears.

Lynn Swann (2001) WR, Steelers.

Fran Tarkenton (1986) QB, Giants, Vikings.

Charley Taylor (1984) WR, RB, Redskins.

Jim Taylor (1976) RB, Packers, Saints.

Lawrence Taylor (1999) LB, Giants. Derrick Thomas (2009) LB, Chiefs.

Thurman Thomas (2007) RB, Bills.

Jim Thorpe (1963) RB, Bulldogs, Indians, Maroons, Independents, Giants, Bulldogs, Cardinals.

Andre Tippett (2008) LB, Patriots.

Y.A. Tittle (1971) QB, Colts, 49ers, Giants.

George Trafton (1964) C, Staleys, Bears.

Charley Trippi (1968) RB, QB, Cardinals.

Emlen Tunnell (1967) DB, Giants, Packers.

Clyde (Bulldog) Turner (1966) C, LB, Bears.

Johnny Unitas (1979) QB, Colts, Chargers.

Gene Upshaw (1987) G, Raiders.

Norm Van Brocklin (1971) QB, Rams, Eagles.

Steve Van Buren (1965) RB, Eagles.

Doak Walker (1986) RB, Lions.

Bill Walsh (1993) Coach, 49ers.

Paul Warfield (1983) WR, Browns, Dolphins.

Bob Waterfield (1965) QB, Coach, Rams.

Mike Webster (1997) C, Steelers.

Roger Wehrli (2007) CB, Cardinals.

Arnie Weinmeister, (1984) DT, Yankees, Giants.

Randy White (1994) DT, Cowboys.

Reggie White (2006) DE, DT, Eagles, Packers, Panthers.

Dave Wilcox (2000) LB, 49ers.

Bill Willis (1977) G, MG, Browns.

Larry Wilson (1978) DB, Cardinals.

Ralph Wilson Jr. (2009) Co-founder AFC, Owner, Bills.

Kellen Winslow (1995) TE, Chargers.

Alex Wojciechowicz (1968) C, LB, Lions, Eagles.

Willie Wood (1989) S, Packers.

Rod Woodson (2009) CB, S, Raiders, Steelers, 49ers.

Rayfield Wright (2006) T, Cowboys.

Ron Yary (2001) OT, Vikings.

Steve Young (2005) QB, Buccaneers, 49ers.

Jack Youngblood (2001) DE, Rams.

Gary Zimmerman (2009) T, Vikings, Broncos.

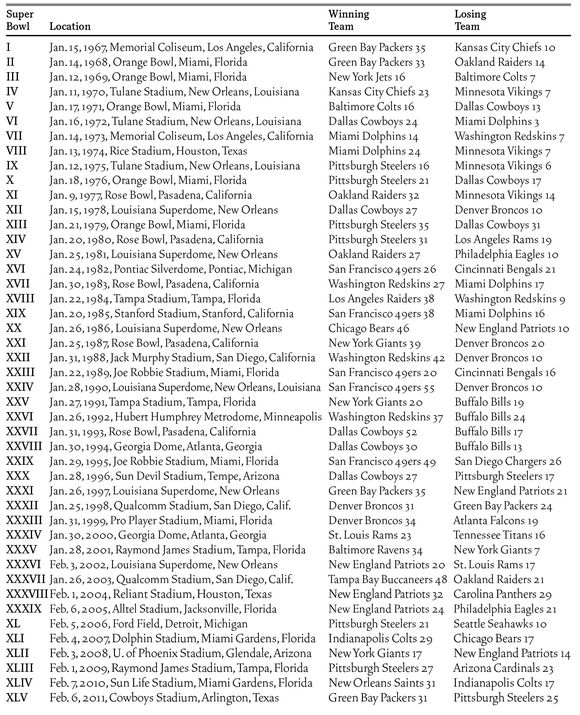

Super Bowl Results