Sentence elements consist primarily of a subject and predicate. Grammarians classify the words in each element as parts of speech. The eight parts of speech are nouns, verbs, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, conjunctions, prepositions, and interjections. We classify words as one or another part of speech according to the role they play in a sentence.

Nouns

Nouns are the names for people, places, animals, things, ideas, actions, states of existence, colors and so forth. In sentences, nouns serve as subjects, objects and complements.

Nouns may also be appositives; that is, they can identify another noun or pronoun, usually by naming it again in different words. In the following sentence bold indicates the appositive (or noun in apposition):

My mother, a police lieutenant, works late every night.

Common nouns name ordinary things: ability, democracy, justice, rope, baseball, desks, library, beauty.

Proper nouns are the names of persons, places, and things. Always capitalize proper nouns: Amtrak, Germany, Donald A. Stone, Greek Orthodox, State Department, General Dynamics, the Rolling Stones, New York.

Compound nouns consist of two or more words that function as a unit. They include such common nouns as heartache, mother-in-law, father-in-law, great-grandmother, and worldview. Compound nouns also may be proper nouns—International Business Machines, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Suez Canal and Sacramento, California.

Verbs

Verbs report action, condition, or state of being. Verbs are the controlling words in predicates, but verbs themselves are controlled by subjects.

Number and person The number of the subject determines the form of its verb. If a subject is only one thing, it is singular. If it is more than one, it is plural: dog is singular; the plural form is dogs. Verbs reflect these differences in subjects by taking a singular or a plural form.

In the first-person singular, I speak or write of myself. In the first-person plural, we speak or write of ourselves. In the second-person singular and plural (the forms are the same), you are addressed. In the third-person singular, someone speaks or writes about somebody or something who is not being addressed. In the third-person plural, someone speaks or writes about more than one person or object.

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| First person | I | we |

| Second person | you | you |

| Third person | she | they |

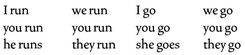

In the present tense the only change that takes place is in the third person singular; a final –s is added to the common form of the verb. Most but not all verbs will add this –s in the third person singular.

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| First person | I build. | We build. |

| Second person | You build. | You build |

| Third person | He builds. | They build. |

Helping verbs or auxiliary verbs enable a single verb to express a meaning that it could not express by itself. A verb phrase is the helping verb plus the main verb. The final word in a verb phrase, the main verb, carries the primary meaning of the verb phrase. Sometimes more than one helping verb accompanies the main verb. In the following sentences, the verb phrases are bold; HV appears over each helping verb, and MV appears over each main verb.

HV MV

He is biking to Vermont from Boston.

HV MV

They will arrive in time for the game.

HV HV MV

Cy Young has always been considered one of the best pitchers in baseball history.

Notice that sometimes words not part of the verb phrase come between the helping verb and the main verb.

Typical helping verbs include: be, being, been, is, am, are, was, were, do, did, does, has, have, had, must, may, can, shall, will, might, could, would, should.

Particles are short words that never change their form no matter how the main verb changes. They sometimes look

like other parts of speech, but they always go with the verb to add a meaning that the verb does not have by itself.

Harry made up with Gloria.

She filled out her application.

Tenses Verbs show whether the action of the sentence is taking place now, took place in the past, or will take place in the future. English has three simple tenses—present, past, and future.

| Present: | She works every day. |

| Past: | She worked yesterday. |

| Future: | She will work tomorrow. |

Irregular verbs form the simple past tense by changing a part of the verb other than the ending.

| Present: | We grow tomatoes every year on our kitchen window shelf. |

| I run four miles every day. | |

| I go to the grocery store every Saturday morning. | |

| Past: | We grew corn back in Iowa. |

| In 1981 Coe ran the mile in three minutes and forty-six seconds. | |

| I went to the grocery store last Saturday. |

Form the future tense of verbs by adding will or shall to the common form of the present.

| Present: | I often read in bed. |

| Future: | I shall read you a story before bedtime. |

| She will read you the ending tomorrow morning. |

Pronouns

A pronoun takes the place of a noun and can serve as subject, object, and complement in sentences. Sentences must always make clear what nouns the pronouns stand for. A pronoun that lacks a clear antecedent (the word for which the pronoun substitutes) causes confusion.

Personal pronouns refer to one or more persons: I, you, he, she, it, we, they.

Indefinite pronouns indicate a member of a group without naming which one we mean: all, any, anyone, each, everybody, everyone, few, nobody, someone.

Reflexive pronouns refer to the noun or pronoun that is the subject of the sentence; they always end in –self or –selves: myself, himself, herself, yourself, ourselves.

She allowed herself no rest.

He loved himself more than he loved anyone else.

Intensive pronouns have the same form as reflexive pronouns; they add special emphasis to nouns and other pronouns.

I myself have often made that mistake.

President Harding himself played poker and drank whiskey in the White House during Prohibition.

Demonstrative pronouns point out nouns or other pronouns that come after them: this, that, these, those.

That is the book I want.

Are those the books you bought?

Relative pronouns join word groups containing a subject and verb to nouns or pronouns that the word groups describe: who, whom, that, which.

Ian McEwan is the writer who won the award for his novel

Atonement.

The tools that I lost in the lake cost me a fortune to replace.

The doctor whom you recommended has left town.

Possessive pronouns show possession or special relations: my, his, her, your, our, their, its. Unlike possessive nouns, possessive pronouns have no apostrophes.

Their cat sets off my allergies.

The fault was ours, and the worst mistake was mine.

Interrogative pronouns introduce questions: who, which, what.

What courses are you taking?

Who kept score?

Which of the glasses is mine?

Like nouns, pronouns can be singular or plural, depending on the noun form they replace.

Adjectives

Adjectives modify nouns and pronouns. That is, they help describe nouns and pronouns in a sentence by answering questions such as which one, what kind, how many, what size, what color, what condition, whose. Adjectives appear in boldface in the sentences below.

The bright yellow sun shone through the gloomy clouds.

Six camels trudged across a vast white desert one scorching afternoon.

Adjectives usually come immediately before, but sometimes immediately after, the words they modify.

The tired, thirsty, impatient horse threw its rider.

The horse, tired, thirsty,and impatient, threw its rider.

Subject complements An adjective modifying the subject of a sentence sometimes appears on the opposite side of a linking verb from the subject.

The horse looked tired, thirsty, and impatient.

My friend was ill, and I was worried.

In these examples, the adjectives are subject complements.

Articles The articles a, an, and the function as adjectives.

He sent me the card in an old envelope.

A and an are indefinite and singular. The article a appears before words that begin with a consonant sound; an appears before words that begin with a vowel sound.

a dish, a year, an apple, an entreaty, a European, a historian, an enemy, a friend, an umbrella, a union, an understanding, an hour

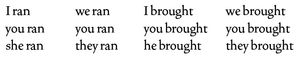

Degree In comparisons, adjectives show degree or intensity by the addition of an –er or –est ending or by the use of more or most or less or least.

Present and past participles of verbs often serve as adjectives:

The trip was both exhausting and rewarding.

The gathering night was filled with stars.

Tired and discouraged, she dropped out of the marathon.

A noun can serve as an adjective.

Cigarette smoking harms our lungs.

People who drive gas guzzlers worsen the energy crisis. Adjectives can also serve as nouns. All the words in boldface in the sentence below are normally adjectives, but here they clearly modify an implicit noun, people or persons. The words therefore assume the function of the implicit noun and become nouns themselves.

The unemployed are not always the lazy and inept.

Avoid adjectives when the sentence requires adverbs Common speech sometimes accepts adjectival forms in an adverbial way; avoid this colloquial usage in writing.

Nonstandard: He hit that one real good.

Revised: He hit that one really well.

Nonstandard: She sure made me work hard for my grade.

Revised: She certainly made me work hard for my grade.

Adverbs

Adverbs usually modify verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs, but they sometimes modify prepositions, phrases, clauses, and even whole sentences.

Adverbs answer questions such as how, how often, to what degree (how much), where, and when.

Wearily he drifted away.

She did not speak much today.

Adverbs may modify by affirmation or negation. Not is always an adverb.

He will surely call home before he leaves.

They shall not pass.

We will never see anyone like her again.

Many adverbs end in –ly, and you can make adverbs of most adjectives simply by adding—ly to the adjective form.

| Adjective | Adverb |

|---|---|

| large | largely |

| crude | crudely |

| beautiful | beautifully |

However, a great many adverbs do not end in–ly: often, sometimes, then, when, anywhere, anyplace, somewhere, somehow, somewhat, yesterday, Sunday, before, behind, ahead, seldom

Note also that many adjectives already end in –ly. costly, stately, lowly, homely, measly, manly, womanly, terribly, honestly

Conjunctive adverbs such as accordingly, consequently, hence, however, indeed, meanwhile, moreover, nevertheless, on the other hand, and therefore connect ideas logically between clauses.

Descartes said, “I think, therefore I am.”

He opposed her before she won the primary election; however, he supported her afterward in her campaign.

Swimming exercises the heart and muscles; on the other

hand, swimming does not control weight as well as jogging and biking do.

Degree Adverbs, like adjectives, show degrees by the addition of an –er or –est ending or by the use of more or most or less or least. Whether modifying an adjective or another adverb, the words more, most, less, and least are themselves adverbs.

Conjunctions

Conjunctions join words or groups of words like clauses or phrases.

Coordinating conjunctions (coordinators) join elements of equal weight or function. The common coordinating conjunctions are and, but, or, for, and nor. Some writers now include yet and so.

She was tired and happy.

The town was small but pretty.

They must be tired, for they have climbed all day long.

You may take the green or the red.

He would not leave the table, nor would he stop insulting his host.

Correlative conjunctions are conjunctions used in pairs. They also connect sentence elements of equal value. The familiar correlatives are both … and, either … or, neither … nor, and not only … but also.

Neither the doctor nor the police believed his story.

Henry Yip not only baked the brownies but also ate every last one of them.

Subordinating conjunctions (subordinators) join dependent or subordinate sections of a sentence to independent sections or to other dependent sections. The common subordinating conjunctions are after, although, as, because, if, rather than, since, that, unless, until, when, whenever, where, wherever and while.

Although the desert may look barren and dead, vigorous life goes on there.

He always wore a hat when he went out in the sun.

Prepositions

Prepositions are words that, with nouns or pronouns, form prepositional phrases and work as modifiers, often specifying place or time. The noun or pronoun is the object of the preposition. In the following sentence the prepositions are bold and their objects are underlined.

Suburban yards throughout America now provide homes for wildlife that once lived only in the country.

The preposition, its noun, and any modifiers attached to the noun make up a prepositional phrase, which acts as adjective or adverb. Prepositions allow the nouns or pronouns that follow them to modify other words in the sentence. Common prepositions include:

about, below, including, under, above, beneath, inside, underneath, across, beside, into, until, after, beyond, like, up, against, by, near, upon, along, despite, of, via, amid, during, on, with, among, except, over, within, as, excluding, since, without, at, following, throughout, before, from, to, behind, in, toward

Some prepositions consist of more than one word.

according to, except for, instead of, along with, in addition to, on account of, apart from, in case of, up to, as to, in front of, with respect to, because of, in place of, with reference to, by means of, in regard to, by way of, in spite of

Prepositions usually come before their objects. But sometimes, especially in questions, they do not. Grammarians debate whether prepositions should end a sentence. Most writers favoring an informal style will now and then use a preposition to end a sentence.

Formal: In what state do you live?

Informal: What state do you live in?

Interjections

Interjections are forceful expressions, usually written with an exclamation point, though mild ones may be set off with commas. They are not used often in formal writing except in dialogue.

Hooray! Ouch! Oh, no! Wow!

“Wow!” Davis said. “Are you telling me that there’s a former presidential adviser who hasn’t written a book?”

How Words Act as Different Parts of Speech

A word that acts as one part of speech in one sentence may act as other parts of speech in other sentences or in other parts of the same sentence. The way the word is used will determine what part of speech it is.

The light glowed at the end of the pier. (noun)

As you light the candle, say a prayer. (verb)

The light drizzle foretold heavy rain. (adjective)

Sentence Structure

The subject is the part of the sentence that names what the sentence is about. The predicate is the part of the sentence that makes a statement or asks a question about the subject. Every sentence contains at least one subject and one predicate that fit together to make a statement, ask a question, or give a command.

Subject The subject and the words that describe it are often called the complete subject. Within the complete subject, the word (or words) that serve as the focus of the sentence may be called the simple subject.

In the following examples, the complete subjects are underscored and the simple subjects are in boldface.

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

The huge black clouds in the west predicted a violent storm.

A compound subject has two or more subjects joined by a

connecting word such as and or but.

Thoughtful acts and kind words have distinguished his administrative career.

Predicate The predicate asserts something about the subject. The predicate, together with all the words that help make a statement about the subject, is often called the complete predicate. Within the complete predicate, the word (or words) that reports or states conditions, with all describing words removed, is called the simple predicate or the verb. A verb expresses action or a state of being.

In the following sentences, complete predicates are underlined and simple predicates (the verbs) are in boldface.

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

The huge black clouds in the west predicted a violent storm.

Thoughtful acts and kind words have distinguished his administrative career.

In a compound predicate, a connecting word joins two or more verbs.

The huge black clouds in the west predicted a violent storm and ended our picnic.

Other Predicate Parts In addition to verbs, complete predicates may also include sentence elements that modify, or help describe, other elements.

Direct objects The direct object tells who or what receives the action done by the subject and expressed by the verb. Not every sentence has a direct object, but transitive verbs (from the Latin trans, meaning “across”) require one to complete their meaning. A transitive verb carries action from the subject across to the direct object. In the examples below, direct objects are in boldface; transitive verbs are underlined.

Catholic missionaries established the school.

I have read that story.

We heard the distant voice.

A verb that does not carry action to a direct object is an intransitive verb. An intransitive verb reports action done by a subject, but it is not action done to anything. The following verbs are intransitive.

The ship sank within three hours after the collision.

She jogs to keep fit.

Indirect objects Sometimes, in addition to a direct object, a predicate also includes a noun or pronoun specifying to whom or for whom the action is done. This is the indirect object. It appears after the verb and before the direct object. Indirect objects are usually used with verbs such as give, ask, tell, sing, and write.

The tenants gave the manager their complaints.

Tell the teacher your idea.

Jack asked George an embarrassing question.

Phrases A phrase is a group of related words without a subject and a predicate.

They were watching the game.

The child ran into the lake.

Grinning happily, she made a three-point shot.

To succeed in writing, you must be willing to revise again and again.

English sentences contain three basic types of phrases: prepositional phrases, verb phrases, and absolute phrases.

Prepositional phrases always begin with a preposition and always end with a noun or pronoun that serves as the object of the proposition. The noun or pronoun in the phrase can then help to describe something else in the sentence. A prepositional phrase generally serves as an adjective or an adverb in the sentence in which it occurs.

Adjective prepositional phrase: The tree in the yard is an oak.

Adverb prepositional phrase: He arrived before breakfast.

Verb phrases are combinations of verbs including a main verb and one or more auxiliary verbs. Verb phrases also can serve as verbals. Verbals include words formed from verbs that do not function as verbs in sentences. There are three kinds of verbals: infinitives, participials, and gerunds.

Infinitives and infinitive phrases The infinitive of any verb except the verb to be is formed when the infinitive marker to is placed before the common form of the verb in the first-person present tense.

| Verb | Infinitive |

|---|---|

| go | to go |

| make | to make |

Infinitives and infinitive phrases function as nouns, adjectives, and adverbs. In the sentences below, examine the various ways the infinitive phrase to finish his novel can function.

To finish his novel was his greatest ambition. (noun, the

subject of the sentence)

He made many efforts to finish his novel. (adjective modifying the noun efforts)

He rushed to finish his novel. (adverb modifying the

verb rushed)

Participles and participial phrases Present participles suggest some continuing action. Past participles suggest completed action. To form the present participle of verbs add –ing to the common present form of the verb. (The present participle being is formed from the infinitive to be.) To form the past participle add –ed to the common present form of the verb. Past participles are frequently irregular. That is, some past participles are formed not by an added –ed, but by an added —en or by a change in the root of the verb.

| Verb | Past Participle |

|---|---|

| bike | biked |

| drive | driven |

| fight | fought |

Because they do represent action, participles serve in a wide variety of ways. They can be part of a verb phrase. Participles can act as adjectives. In the sentence below, the participial phrase modifies the subject.

Insulted by the joke, the team stormed out of the banquet.

Gerunds and gerund phrases A gerund is the present participle used as a noun. A gerund phrase includes any words and phrases attached to the gerund so that the whole is a noun serving as a subject or an object.

Walking is one of life’s great pleasures. (subject)

He worked hard at typing the paper. (object)

Absolute phrases consist of a noun or pronoun attached to a participle without a helping verb. It modifies the whole sentence in which it appears. (Including a helping verb would make the participle part of a verb phrase.)

Her body falling nearly a hundred miles an hour, she pulled the ripcord and the parachute opened with a heavy jerk.

Falling nearly a hundred miles an hour, she pulled the ripcord, and the parachute opened with a heavy jerk.

The storm came suddenly, the clouds boiling across the sky.

Clauses A clause is a group of grammatically related words containing both a subject and a predicate. An independent clause can usually stand by itself as a complete sentence. A dependent, or subordinate, clause often cannot stand by itself because it is introduced by a subordinating conjunction or a relative pronoun and therefore the clause alone does not make sense. In the sentences below, the independent clauses are in boldface, the dependent clauses in italics.

She ran in the marathon because she wanted to test herself.

When we had done everything possible, we left the wounded to the enemy.

Noun clauses A noun clause is a clause that acts as a subject, object, or complement.

Subject: That English is a flexible language is both its glory and its pain.

Object: He told me that English is a flexible language.

Complement: His response was that English is a flexible language.

Adjective clauses An adjective (or adjectival) clause modifies a noun or pronoun. A relative pronoun connects the adjective clause to the word it modifies.

The contestant whom he most wanted to beat was his father.

Here, the adjective clause modifies the noun contestant; the relative pronoun whom, which stands for its antecedent contestant, serves as the direct object of the infinitive to beat.

The computer that I wanted cost too much money.

Here the adjective clause modifies the noun computer; the relative pronoun that serves as the direct object of the verb wanted.

The journey of Odysseus, which is traceable even today on a map of Greece and the Aegean Sea, made an age of giants and miracles seem close to the ancient Greeks.

The adjective clause modifies journey; the relative pronoun which serves as the subject of the verb phrase is visible.

Adverb clauses An adverb (or adverbial) clause serves as an adverb, frequently (but not always) modifying the verb in another clause. The subordinators after, when, before, because, although, if, though, whenever, where, and wherever, as well as many others, can introduce adverb clauses.

After we had talked for an hour, he began to look at his watch. (The adverb clause modifies the verb began.)

He ran as swiftly as he could. (The adverb clause modifies the adverb swiftly.)

The desert was more yellow than he remembered. (The adverb clause modifies the adjective yellow.)

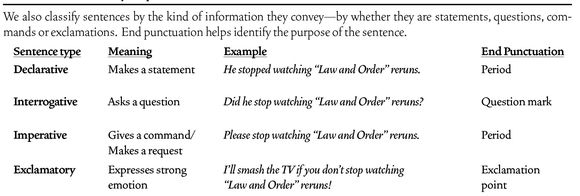

Sentence Types

Grammarians classify sentences by numbers of clauses and

how the clauses are joined. The basic sentence types in English are simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex. Another classification of sentences is by purpose: declarative, interrogative, imperative, and exclamatory.

Simple sentences A simple sentence contains only one clause, and that clause is independent, able to stand alone grammatically. A simple sentence may have several phrases, a compound subject, and a compound verb. The following are simple sentences, each with one independent clause.

The bloodhound is the oldest known breed of dog.

He staked out a plot of high ground in the mountains, cut down the trees, and built his own house with a fine view of the valley below.

Historians, novelists, short-story writers, and playwrights write about characters, design plots, and usually seek the dramatic resolution of a problem.

Compound sentences A compound sentence contains two or more independent clauses, usually joined by a comma and a coordinating conjunction such as and, but, nor, or, for, yet, or so. A compound sentence does not contain a dependent clause. Sometimes a semicolon, a dash, or a colon joins the independent clauses.

The sun blasted the earth, and the plants withered and died. He asked directions at the end of every street; his wife sighed in frustration.

A compound sentence also may consist of a series of independent clauses joined by commas or semicolons, usually but not always with a conjunction before the last clause.

They searched the want ads, she visited real estate agents, he drove through neighborhoods seeking for-sale signs, and they finally located a house big enough for them and their pet rattlesnakes.

The trees on the ridge behind our house change in September: the oaks redden; the maples pass from green to orange; the pines grow darker.

Complex sentences A complex sentence contains one independent clause and one or more dependent clauses. In the following sentences, the dependent clause is in boldface type.

He consulted the dictionary because he did not know how to pronounce the word.

She asked people if they approved of what the speaker said.

Compound-complex sentences A compound-complex sentence contains two or more independent clauses and at least one dependent clause. In the following sentences, boldface type indicates dependent clauses.

She discovered a new world in international finance, but she worked so hard investing other people’s money that she had no time to invest any of her own.

After Abraham Lincoln was killed, the government could not determine how many conspirators there were; and since John Wilkes Booth, the assassin, was himself soon killed, he could not clarify the mystery, which remains to this day.

Correct Verb Usage

Verbs can take a variety of forms, depending on how we use them.

Basic Tense There are three basic tenses in English—present, past, and future.

Sentence Classification by Purpose

Simple present The simple present of most verbs is the dictionary form, which is also called the present stem. Usually, to form the third-person singular from the simple present, add —s or —es to the present stem.

The simple present has several uses. It makes an unemphatic statement about something happening or a condition existing right now.

The earth revolves around the sun.

The car passes in the street.

It expresses habitual or continuous or characteristic action.

Porters carry things.

Dentists fill teeth and sometimes pull them.

It expresses a command indirectly, as a statement of fact.

Periodicals are not to be taken out of the room.

It reports the content of literature, documents, movies, musical compositions, works of art, or anything else that supposedly comes alive in the present each time it is experienced by an audience.

Macbeth is driven by ambition, and he is haunted by ghosts.

The Parthenon in Athens embodies grace, beauty, and calm.

Simple past To form the simple past of regular verbs, add —d or —ed to the present stem. The simple past does not change form.

| I escaped | we escaped |

| you escaped | you escaped |

| he escaped | they escaped |

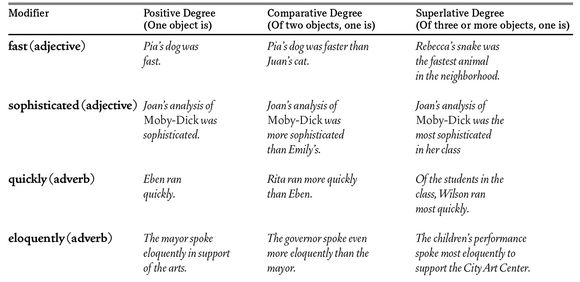

Sometimes the simple past is irregular. Irregular verbs form the simple past tense not with —d or —ed but by some other change, often a change in an internal vowel.

Infinitive: to run

Simple future Use the helping verbs shall and will to make the simple future.

| I shall go | we shall go |

| you will go | you will go |

| she will go | they will go |

Traditional grammar holds that shall should be used for the first person, will for the second and third persons. In practice, this distinction is often ignored; most people write: “I will be 25 years old on my next birthday.”

The Three Perfect Tenses In addition to the simple present, past, and future, English verbs have three perfect tenses—the present perfect, the past perfect, and the future perfect. The perfect tense expresses an act that will be completed before an act reported by another verb takes place. For that reason, a verb in the perfect tense should always be thought of as paired with another verb, either expressed or understood.

Present perfect In the present perfect tense, the action of the verb started in the past. The present perfect is formed by the helping verb has or have plus the past participle.

She has loved architecture for many years, and now she takes architecture courses in night school.

I have worked hard for this diploma.

Past perfect The past perfect tense reports an action completed before another action took place. The past perfect is also formed with the past participle, but it uses the helping verb had.

I had worked twenty years before I saved any money.

The past perfect, like the present perfect, implies another act that is not always stated in the sentence.

He had told me that he would quit if I yelled at him. I yelled at him, and he quit.

Future perfect The future perfect tense reports an act that will be completed by some specific time in the future. It is formed by the helping verb shall or will added to have or has and the past participle.

I shall have worked 50 years when I retire.

He will have lived with me 10 years next March.

The Progressive Form The progressive form shows that an action continues during the time that the sentence reports, whether that time is past, present, or future. It is made with the present participle and a helping verb that is a form of to be.

Present progressive: I am working.

Past progressive: I was working.

Future progressive: They will be working.

Present perfect progressive: She has been working.

Past perfect progressive: We had been working.

Future perfect progressive: They will have been working.

Here are some more examples of progressive forms:

I am writing a new book.

I was making soup in the kitchen when the house caught fire.

They will be painting the garage tomorrow afternoon.

Principal Parts of the Most Common Irregular Verbs Many verbs are irregular: their past tense and their past participle are not formed simply by an added –ed. If the verb is regular, a dictionary will list only the present form. Form both the past and the past participle by adding –d or —ed to this form. If the verb is irregular, a dictionary will give the forms of the principal parts.

The most important irregular verb is to be, often used as a helping verb. It is the only English verb that does not use the infinitive as the basic form for the present tense.

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Present: | I am | we are |

| you are | you are | |

| she is | they are | |

| Past: | I was | we were |

| you were | you were | |

| it was | they were | |

| Past perfect: | I had been | we had been |

| you had been | you had been | |

| he had been | they had been |

Mood The mood of a verb expresses the attitude of the writer. Verbs have several moods—indicative, subjunctive, imperative and conditional.

Indicative mood The indicative is used for simple statements of fact or for asking questions about fact. It is by far the most common mood of verbs in English.

The tide came in at six o’clock and swept almost to the foundation of our house.

Common Irregular Verbs

| Present | Past | Past participle |

|---|---|---|

| awake | awoke | awoke/awakened |

| become | became | become |

| begin | began | begun |

| blow | blew | blown |

| break | broke | broken |

| bring | brought | brought |

| burst | burst | burst |

| choose | chose | chosen |

| cling | clung | clung |

| come | came | come |

| dive | dived | dived |

| do | did | done |

| draw | drew | drawn |

| drink | drank | drunk |

| drive | drove | driven |

| eat | ate | eaten |

| fall | fell | fallen |

| fly | flew | flown |

| forget | forgot | forgotten/forgot |

| forgive | forgave | forgiven |

| freeze | froze | frozen |

| get | got | gotten/got |

| give | gave | given |

| go | went | gone |

| grow | grew | grown |

| hang (things) | hung | hung |

| hang (people) | hanged | hanged |

| know | knew | known |

| lay (to put) | laid | laid |

| lie (to recline) | lay | lain |

| lose | lost | lost |

| pay | paid | paid |

| ride | rode | ridden |

| ring | rang | rung |

| rise | rose | risen |

| say | said | said |

| see | saw | seen |

| set | set | set |

| shake | shook | shaken |

| shine | shone/shined | shone/shined |

| show | showed | shone |

| sing | sang | sung |

| sink | sank | sunk |

| sit | sat | sat |

| speak | spoke | spoken |

| spin | spun | spun |

| spit | spat/spit | spat/spit |

| steal | stole | stolen |

| strive | strove/strived | striven/strived |

| swear | swore | sworn |

| swim | swam | swum |

| swing | swung | swung |

| take | took | taken |

| tear | tore | torn |

| tread | trod | trod/trodden |

| wake | woke | waked/woke/wakened |

| wear | wore | worn |

| weave | wove | woven |

| wring | wrung | wrung |

| write | wrote | written |

Subjunctive mood The subjunctive conveys a wish, a desire, or a demand in the first or third person, or it makes a statement contrary to fact.

I wish I were a bird.

Helen wishes she were home.

He asked that she never forget him.

If only I were in Paris tonight!

The subjunctive form for most verbs differs from the indicative only in the first and third person singular. The present subjunctive of the verb to be is were for the first, second, and third persons, singular and plural.

Were she my daughter, I would not permit her to date a member of a motorcycle gang.

If we were born with wings, we could learn to fly.

When the subjunctive is used with the verb to be to express commands or wishes in the third person singular or the future tense in the first or third person, the verb form is be.

If I be proved wrong, I shall eat my hat.

If this be treason, make the most of it!

Use the subjunctive in clauses beginning with that after verbs that give orders or advice or express wishes or requests.

He wishes that she were happier.

She asked that he draw up a marriage contract before the wedding.

In the examples above, a request appears in a that clause. Since no one can tell whether a request will be honored or not, the verb clause is in the subjunctive. Should and had may also express the subjunctive.

Should he step on a rattlesnake, his boots will protect him.

Had he taken my advice, he would not have eaten raw cranberries.

Do not confuse the conditional with the past subjunctive:

Incorrect: I wish we would have won the tournament.

Correct: I wish we had won the tournament.

Imperative mood The imperative expresses a command or entreaty in the second person singular or plural, and the form of the verb is the same as the indicative.

In the imperative sentence, the subject of the verb is always you, but you is usually understood, not written out.

Pass the bread.

Watch your step!

Sometimes you is included for emphasis.

You give me my letter this instant!

Conditional mood The conditional makes statements that depend on one another; one is true on condition of the other’s being true. A conditional sentence contains a clause that states the condition and another that states the consequence of the condition. Most conditional statements are introduced with if.

If communist governments had been able to produce enough food for their people, they would not have collapsed in 1989.

If you will be home tonight, I’ll come to visit.

Even if the strike is settled, the workers will still be angry.

Like the indicative, the conditional requires no changes in ordinary verb forms. Distinguish the conditional from the subjunctive. Use the subjunctive only for conditions clearly contrary to fact.

If the circumstances are in the past, use the subjunctive for conditions that were clearly not factual and the indicative for conditions that may have been true. Use would or could as a helping verb for statements that give the supposed consequences of conditions that were not factual.

If he were there that night, he would have had no excuse.

He was not there; the if clause uses the subjunctive, and the clause stating the consequences uses would.

If he was there, he had no excuse.

He may have been there; we do not know. If he was indeed there, he had no excuse. The indicative mood is used in both clauses as a simple statement of fact.

Use the past perfect in past conditional statements when the condition states something that was not true.

If Hitler had stopped in 1938, World War II would not have come as it did.

Avoid using the conditional in both clauses.

Incorrect: If she would have gone to Paris, she would have had a good time.

Correct: If she had gone to Paris, she would have had a good time.

Do not confuse the conditional with the past subjunctive.

Incorrect: I wish we would have won the tournament.

Correct: I wish we had won the tournament.

Active and Passive Voice Use verbs in the active voice in most sentences; use verbs in the passive voice sparingly and only for good reason.

The voice of a transitive verb tells whether the subject is the actor in the sentence or is acted upon. (A transitive verb carries action from an agent to an object. A transitive verb can take a direct object; an intransitive verb does not

take a direct object.) Intransitive verbs cannot be passive.

When transitive verbs are in the active voice, the subject does the acting. When transitive verbs are in the passive voice, an agent—either implied or expressed in a prepositional phrase—acts upon the subject.

Active: He burned the arroz con pollo.

Passive: The arroz con pollo was burned by him.

The arroz con pollo was burned.

Readers usually want to know the agent of an action; that is, they want to know who or what does the acting. Since the passive often fails to identify the agent of an action, it suggests evasion of responsibility.

Active: The senator misplaced the memo.

Passive: The memo was misplaced.

Use the passive when the recipient of the action in the sentence is much more important to the statement than the doer of the action.

My car was stolen last night.

Who stole your car is not known. The important thing is that the car was stolen.

Scientific researchers generally use the passive voice throughout reports on experiments to keep the focus on the experiment rather than on the experimenters.

When the bacteria were isolated, they were treated carefully with nicotine and were observed to stop reproducing.

Infinitives The infinitive is the present tense of a verb with the marker to. Grammatically, the infinitive can complete the sense of other verbs, serve as a noun, and form the basis of some phrases.

The present infinitive, which uses the infinitive marker to along with the verb, describes action that takes place at the same time as the action in the verb the infinitive completes.

He wants to go.

He wanted to go.

He will want to go.

The present perfect infinitive, which uses the infinitive marker to, the verb have and a past participle, describes action prior to the action of the verb whose sense is completed by the infinitive. The present perfect infinitive often follows verb phrases that include should or would.

I would like to have seen her face when she found the duck in her bathtub.

An infinitive phrase includes the infinitive and the words that complete its meaning.

He studied to improve his voice.

Sometimes the infinitive marker is omitted before the verb, especially after such verbs as hear, help, let, see and watch.

They watched the ship sail out to sea.

In general, avoid split infinitives. A split infinitive has one or more words awkwardly placed between the infinitive marker to and the verb form. The rule against split infinitives is not absolute: some writers split infinitives and others do not. But the words used to split infinitives can usually go outside the infinitive, or they can be omitted altogether.

| Split infinitive: | He told me to really try to do better. |

| Enrique wanted to completely forget his painful romance. | |

| Revised: | He told me to try to do better. |

| Enrique wanted to forget his painful romance completely. |

Correct Pronoun Usage

Pronouns take the places of nouns in sentences. Most pronouns require an antecedent to give them content and meaning. The antecedent is the word for which the pronoun substitutes. The antecedent usually appears earlier in the same sentence or in the same passage. In the following example, the antecedent for the pronoun it is snow.

The snow fell all day long, and by nightfall it was three feet deep.

Pronoun Reference Rewrite sentences with pronouns that do not refer clearly to their antecedents or that are widely separated from them.

Confusing:

Albert was with Emanuel when he got the news that his rare books had arrived.

Who got the news? Did the rare books belong to Emanuel, or did they belong to Albert?

Improved:

When Albert got the news that his rare books had arrived, he was with Emanuel.

Generally, personal pronouns refer to the nearest previous noun, but don’t risk a potentially unclear antecedent. Revise the sentence.

Pronoun Agreement Pronouns must agree with their antecedents in number and gender. Singular antecedents require singular pronouns. Plural antecedents require plural pronouns.

The house was dark and gloomy, and it sat in a grove of tall cedars that made it seem darker still.

The cars swept by on the highway, all of them doing more than 55 miles per hour.

Use a singular pronoun when all the parts of a compound antecedent are singular and the parts are joined by or or nor. Notice, too, how the pronouns in the following examples also agree with their antecedents in gender, or sexual reference in grammar.

Either Ted or John will take his car.

Neither Judy nor Linda will lend you her scalpel.

Antecedents of unknown gender Do not use the masculine singular pronoun to refer to a noun or pronoun of unknown gender.

Awkward:

Any teacher must sometimes despair at the indifference of his students.

Everybody can have what he wants to eat.

Such language, though grammatically correct, is now viewed as sexist. Avoid sexist language by changing nouns and pronouns to plural forms, or revise the sentence in some other way.

Improved:

Any teacher must sometimes despair at the indifference of students.

Teachers must sometimes despair at the indifference of their students.

When referring to the whole, collective nouns—team, family, audience, majority, minority, committee, group, government, flock, herd and many others—use singular pronouns.

The team won its victory gratefully.

The committee disbanded when it finished its business.

However, if the members of the group indicated by a collective noun are considered as individuals, use a plural pronoun.

Common Errors in Verbs

| Faulty | Correct | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Irregular verbs | |||

| Avoid confusing simple past with past participle. | I seen her last night. | I saw her last night. | |

| He done it himself. | He did it himself. | ||

| He had done it himself. | |||

| Don’t try to make irregular verbs regular. | She drawed my picture. | She drew my picture. | |

| We payed for everything. | We paid for everything. | ||

| Transitive and intransitive verbs | |||

| Don’t confuse lay (transitive) with lie (intransitive). | I lay awake every night. | I lie awake every night. | |

| I lay my books on the desk when I came in. | I laid my books on the desk when I came in. | ||

| I laid down for an hour. | I lay down for an hour. | ||

| Don’t confuse set (transitive) with sit (intransitive). | He pointed to a chair, so I set down. | He pointed to a chair, so I sat down. | |

| She sat the vase on the table. | She set the vase on the table. | ||

| Tense | |||

| Don’t shift tenses illogically. | The car bounced over the curb and comes crashing through the window. | The car bounced over the curb and came crashing through the window. | |

| Mood | |||

| Don’t confuse conditional with past subjunctive. | I wish he would have arrived sooner. | I wish he had arrived sooner. | |

| I would have been here if you would have told me you | I would have been here if you had told me you were performing. | ||

The hard-rock band broke up and began fighting among themselves when their leader quit.

Pronouns without references Pronouns such as this, that, they, it, which and such sometimes refer not to a specific antecedent, but to the general idea expressed by a whole clause or sentence. Using pronouns in this way is imprecise and often misleading.

Andy Warhol once made a movie of a man sleeping for a whole night, which was a tiresome experience.

Was the movie tiresome to watch? Or was making the movie the tiresome experience?

“It” as Pronoun and Expletive The pronoun it always has an antecedent; the expletive it serves as a grammatical subject when the real subject comes after the verb or is understood.

Pronoun:

In rural America when a barn burns, it often takes with it a year’s hard work for a farm family.

Expletive:

In rural America, when a barn burns, it is difficult for a farm family to recover from the loss.

The expletive it serves as the grammatical subject of the independent clause that it begins. Avoid using the expletive it and the pronoun it one after the other.

Weak:

What will happen to the kite? If it is windy, it will fly.

Improved:

What will happen to the kite? It will fly if the wind blows.

The expletive it does not require an antecedent. But other pronouns used without antecedents are both awkward and unclear.

Some Rules for Using Pronouns

The subject of a dependent clause is always in the subjective case, even when the dependent clause serves as the object for another clause.

The subject of a dependent clause is always in the subjective case, even when the dependent clause serves as the object for another clause.Dr. Hiromichi promised the prize to whoever made the best grades.

Leave the message with whoever comes into the house first.

Objects of prepositions, direct objects, and indirect objects always take the objective case.

Objects of prepositions, direct objects, and indirect objects always take the objective case.She called him and me fools.

It was a secret between you and me.

When a noun follows a pronoun in an appositive construction, use the case for the pronoun that you would use if the noun were not present. The presence of the noun does not change the case of the pronoun.

When a noun follows a pronoun in an appositive construction, use the case for the pronoun that you would use if the noun were not present. The presence of the noun does not change the case of the pronoun.He gave the test to us students.

We students said that the test was too hard.

Than and as often serve as conjunctions introducing implied clauses. In these constructions the idea that follows a pronoun at the end of a sentence is understood, not stated. The case of the pronoun depends on how the pronoun is used in the clause if it were written. (Implied clauses are sometimes called elliptical clauses.)

Than and as often serve as conjunctions introducing implied clauses. In these constructions the idea that follows a pronoun at the end of a sentence is understood, not stated. The case of the pronoun depends on how the pronoun is used in the clause if it were written. (Implied clauses are sometimes called elliptical clauses.)Throughout elementary school, Elizabeth was taller than he.

The Sanchezes are much richer than they.

Pronouns that are the subjects or the objects of infinitives take the objective case.

Pronouns that are the subjects or the objects of infinitives take the objective case.I believe them to be tedious and ordinary.

Use the possessive case before a gerund (an –ing verb form used as a noun). Use the subjective or objective case with present participles used as adjectives.

Use the possessive case before a gerund (an –ing verb form used as a noun). Use the subjective or objective case with present participles used as adjectives.Gerund:

His returning the punt 96 yards for a touchdown spoiled the bets made by the gamblers.

Present participle:

They remembered him laughing as he said goodbye.

Pronouns agree in case with the nouns or pronouns with which they are paired.

Pronouns agree in case with the nouns or pronouns with which they are paired.Compound:

She and Carla ran a design studio.

Appositive: The captain chose two crew members, her and me, to attempt the rescue.

The last two crew members on board, Carla and I, drew the first watch.

Using Adjectives and Adverbs Correctly

Adverbs and Adjectives with Verbs of Sense Verbs of sense (smell, taste, feel and so on) can be linking or nonlinking. Decide whether the modifier after a verb of sense serves the verb (adverb) or the subject (adjective).

Adverb: I felt badly. (referring to the sense of touch)

Adjective: I felt bad because she heard me say that her baby looked like a baboon. (referring to emotions)

Distinguishing Adjectives and Adverbs Spelled Alike Not every adverb is an adjective with –ly tacked

to the end of it. In standard English, many adverbs do not require the –ly, and some words have the same form whether they are used as adjectives or as adverbs.

Words that are both adjectives and adverbs: fast, hard, only, right, straight.

Using Adjectives and Adverbs for Comparison Writers often use adjectives and adverbs to compare. Usually an –er or an –est ending on the word or the use of more or most along with the word indicates the degree, amount, or quality.

The simplest form of the adjective or the adverb is the positive degree, the form used when no comparison is involved. This is the form found in a dictionary.

To compare two things, use the comparative degree. Form the comparative degree of many adjectives by adding the suffix –er, or by using the adverb more or less with the positive form. Use the adverb more or less to form the comparative of most adverbs.

Use the superlative degree of both adjectives and adverbs to compare more than two things. Form the superlative of an adjective by adding the suffix –est to the positive form, or by using the adverb most or least with the positive form. The adverb most or least is used to form the superlative degree of an adverb.

Formal grammatical rules reserve the –er and –est endings for comparative and superlative degrees of adjectives and adverbs of no more than two syllables. Yet common usage for these modifiers of degree draws on suffix endings interchangeably with the forms more and most, less and least.

Irregular adjectives and adverbs Some adjectives and adverbs are irregular; they change form to show degree.

| Positive | Comparative | Superlative |

|---|---|---|

| bad | worse | worst |

| good | better | best |

| little | less | least |

| many/much | more | most |

| far | farther | farthest |

Using degrees correctly

Do not use the superlative for only two things or units.

Do not use the superlative for only two things or units.Not: Of the two brothers, John was the quickest.

But: Of the two brothers, John was the quicker.

Do not use the comparative and superlative degrees with absolute adjectives. Absolutes are words that in themselves mean something complete or ideal, such as unique, half, infinite, impossible, perfect, round, square, destroyed, and demolished. If something is unique, it is the only one of its kind. We cannot say, “Her dresses were more unique than his neckties.” Either something is unique or it is not. No degrees of uniqueness are possible. “The answer to your question is more impossible than you think,” is also wrong. Something is either possible or impossible; it cannot be more or less impossible.

Do not use the comparative and superlative degrees with absolute adjectives. Absolutes are words that in themselves mean something complete or ideal, such as unique, half, infinite, impossible, perfect, round, square, destroyed, and demolished. If something is unique, it is the only one of its kind. We cannot say, “Her dresses were more unique than his neckties.” Either something is unique or it is not. No degrees of uniqueness are possible. “The answer to your question is more impossible than you think,” is also wrong. Something is either possible or impossible; it cannot be more or less impossible. Avoid using the superlative when no comparison is stated.

Avoid using the superlative when no comparison is stated.Dracula is the scariest movie!

The scariest movie ever filmed? The scariest movie ever viewed? The scariest movie ever shown in town? In common speech expressions such as scariest movie or silliest thing often do not in fact compare the movie or the thing with anything else. In writing, such expressions take up space without conveying any precise meaning.

Avoid adding an unnecessary adverb to the superlative degree of adjectives.

Avoid adding an unnecessary adverb to the superlative degree of adjectives.Not: She was the very brightest person in the room.

But: She was the brightest person in the room.

Not: The interstate was the most shortest way to Nashville.

But: The interstate was the shortest way to Nashville.

Avoid making illogical comparisons with adjectives and adverbs. Illogical comparisons occur when writers leave out some necessary words.

Avoid making illogical comparisons with adjectives and adverbs. Illogical comparisons occur when writers leave out some necessary words.Illogical: The story of the Titanic is more interesting than the story of any disaster at sea.

This comparison makes it seem that the story of the Titanic is one thing and that the story of any disaster at sea is something different. In fact, the story of the Titanic is about a disaster at sea. Is the story of the Titanic more interesting than itself?

Corrected: The story of the Titanic is more interesting than the story of any other disaster at sea.

Overuse of Adjectives and Adverbs Too many adjectives or adverbs can weaken the force of a statement. Strong writers put an adjective before a noun or pronoun only when the adjective is truly needed. They rarely put more than one adjective before a noun unless they need to create some special effect or unless one of the adjectives is a number or part of a compound noun, such as high school or living room.

The clean and brightly lit dining car left a cold and snowy

Moscow well stocked with large and sweet fresh red apples, many oranges, long green cucumbers, delicious chocolate candy, and countless other well-loved delicacies.

Improved: The dining car left Moscow well stocked with fresh apples, oranges, cucumbers; chocolate candy; and other little delicacies.

Use adverbs in the same careful way. Instead of piling them up, use strong verbs that carry the meaning.

Weak: The train went very swiftly along the tracks.

Improved: The train sped along the tracks.

Misplaced Modifiers Most adjectives and adjectival clauses and phrases should stand as close as possible to the words that they modify. Misplacing the modifier can lead to unintended, and usually confusing and humorous, results.

In general it is easier to separate adverbs and adverbial phrases from the words that they modify than adjectives from the words that they modify.

Dangling Participles Introductory participles and participial phrases must modify the grammatical subject of the sentence. Participles that do not modify the grammatical subject are called dangling or misplaced participles. A dangling participle lacks a noun to modify.

Incorrect:

Driving along Route 10, the sun shone in Carmela’s face. (The sun is driving along Route 10?)

Using elaborate charts and graphs, the audience understood the plan.

(The audience used the charts?)

Running down the street, the fallen lamppost stopped her suddenly.

(The lamppost ran down the street?)

Revised:

Driving along Route 10, Carmela found the sun shining in her face.

or

As Carmela drove along Route 10, the sun shone in her face.

Using elaborate charts and graphs, the mayor explained the plan to the audience.

or

Because the mayor used elaborate charts and graphs, the audience understood the plan.

Running down the street, she saw the fallen lamppost, which stopped her suddenly.

or

As she ran down the street, the fallen lamppost stopped her suddenly.

Informal usage frequently accepts use of an introductory participle as a modifier of the expletive it, especially when the participle expresses habitual or general action.

Walking in the country at dawn, it is easy to see many species of birds.

The statement expresses something that might be done by anyone. Many writers and editors would prefer this revision: “Walking in the country at dawn is an easy way to see many species of birds.”

Prepositional Phrases Prepositional phrases used as adjectives seldom give trouble. Prepositional phrases used as adverbs, however, are harder to place in sentences, and misplaced adverbial phrases can lead readers astray.

Confusing:

He saw the first dive bombers approaching from the bridge of the battleship.

The multipurpose knife was introduced to Americans on television .

He ran the 10-kilometer race from the shopping mall through the center of town to the finish line by the monument in his bare feet.

Revised:

From the bridge of the battleship, he saw the first dive bombers approaching.

The multipurpose knife was introduced on television to Americans.

In his bare feet he ran the 10-kilometer race from the shopping mall through the center of town to the finish line by the monument.

or

From the shopping mall through the center of town to the finish line by the monument he ran the 10-kilometer race in his bare feet.

Clauses A misplaced clause is one that modifies the wrong element of the sentence.

Confusing: Professor Peebles taught the course on the English novel that most students dropped after three weeks. Revised: Professor Peebles taught the course on the English

novel, a course that most students dropped after three weeks.

Placing Adverbs Correctly Adverbs can modify what precedes or what follows them. Avoid the confusing adverb or adverbial phrase that seems to modify both the element that comes immediately before it and the element that comes immediately after it.

Confusing:

To read a good book completely satisfies her.

To speak in public often makes her uncomfortable.

Revised:

She is completely satisfied when she reads a good book.

or

She is satisfied when she reads a good book completely.

or

When she speaks in public often, she feels uncomfortable.

or

Often she feels uncomfortable when she speaks in public.

Be cautious when you use adverbs to modify whole sentences. Some adverbs are much more ambiguous when they modify full sentences.

Confusing: Hopefully he will change his job before this one gives him an ulcer.

Who is doing the hoping?

Revised: We hope he will change his job before this one gives him an ulcer.

Confusing: Briefly, Tom was the source of the trouble.

Does the writer wish to say, briefly, that Tom was the source of the trouble? Or was Tom the source of the trouble, but only briefly?

Revised: To put it briefly, Tom was the source of the trouble.

Put Limiting Modifiers in Logical Places In speaking, modifiers can work in illogical places because the sense is clear from tone of voice, gesture or general context. In writing, the lack of logic that results from misplacement of modifiers can cause confusion. Limiting modifiers, words such as merely, completely, fully, perfectly, hardly, nearly, almost, even, just simply, scarcely and only, must stand directly before the words or phrases they modify.

Confusing: He only had one bad habit, but it just was enough to keep him in trouble.

Revised: He had only one bad habit, but it was just enough to keep him in trouble.

Forming Degrees of Adjective and Adverb Modifiers

Period

Use a period after a sentence that makes a statement, gives a mild command or makes a mild request, or asks a question indirectly. Simple statements end with a period.

Statement: The building burned down last night

Mild command: Lend me a car, and I’ll do the shopping.

Indirect question:

She asked me where I had gone to college and who my adviser was.

Question Mark

Use a question mark after a direct question, but not after an indirect question.

Who wrote Wuthering Heights?

She wanted to know who wrote Wuthering Heights.

If a question ends with a quoted question, one question mark serves for both the question in the main clause and the question that is quoted.

What did Juliet mean when she cried, “O Romeo, Romeo!

Wherefore art thou Romeo?”

For a quoted question before the end of a sentence that makes a statement, place a question mark before the last quotation mark and put a period at the end of the sentence.

“What did the president know and when did he know it?” became the great question of the Watergate hearings.

Occasionally a question mark changes a statement into a question.

You expect me to believe a story like that?

He drove my car into your kitchen?

Exclamation Point

Use exclamation points sparingly to convey surprise, shock, or some other strong emotion.

The land of the free! This is the land of the free! Why, if I say anything that displeases them, the free mob will lynch me, and that’s my freedom.—D. H. Lawrence

Moon, rise! Wind, hit the trees, blow up the leaves! Up, now, run! Tricks! Treats! Gangway!—Ray Bradbury

Commands showing strong emotion also use exclamation points.

Stay away from the stove!

Help!

Avoid using too many exclamation marks.

Commas

With Independent Clauses Use commas to set off independent clauses joined by the common coordinating conjunctions and, but, or, nor, for, yet, and so.

Her computer broke down, and she had to write with a pencil.

He won the Heisman Trophy, but no professional team drafted him.

The art majors could paint portraits, or they could paint houses.

Some writers do not separate short independent clauses with a comma.

He stayed at home and she went to work.

With Long Introductory Phrases and Clauses Use commas after long introductory phrases and clauses.

After he had sat in the hot tub for three hours, the fire department had to revive him.

If you plan to lose 50 or more pounds, you should take the advice of a doctor.

A short opening phrase does not require a comma after the phrase.

After the game I drifted along with the happy crowd.

In their coffeehouses 18th-century Englishmen conducted many of their business affairs.

Always put a comma after an introductory subordinate clause.

When we came out, we were not on the busiest Chinatown street but on a side street across from the park.—Maxine Hong Kingston

Commas also set off introductory interjections, transitional expressions, and names in direct address.

Yes, a fight broke out after the game.

Nevertheless, we should look on the bright side.

Pablo, why are you doing this?

With Clauses and Phrases That Modify

Setting off absolutes An absolute is set off from the rest of the sentence by a comma. An absolute is a phrase that combines a noun with a present or past participle and that serves to modify the entire sentence.

The bridge now built, the British set out to destroy it.

The snake slithered through the tall grass, the sunlight shining now and then on its green skin.

Setting off participial modifiers Use commas to set off participial modifiers at the beginning or end of a sentence.

Having learned that she failed the test, Marie had a sleepless night.

We climbed the mountain, feeling the spring sunshine and intoxicated by the view.

With Nonrestrictive Clauses and Phrases Use commas to set off nonrestrictive clauses and phrases. Nonrestrictive clauses and phrases can be lifted out of sentences without any resultant change in the primary meaning of the sentences. The paired commas that set off a nonrestrictive clause or phrase announce that these words provide additional information.

My dog Lady, who treed a cat last week, treed the mailman this morning.

In the midst of the forest, hidden from the rest of the world, stood a small cabin.

Setting off a phrase or a clause with commas can often change the meaning of a sentence. In this sentence the commas make the clauses nonrestrictive.

The commencement speaker, who was a sleep therapist, spoke for three hours.

There was only one commencement speaker, and that speaker happened to be a sleep therapist.

The commencement speaker who was a sleep therapist spoke for three hours.

In this sentence, the absence of commas means that there must have been more than one speaker. The clause is restrictive: it defines the noun and is essential to its meaning. The writer must single out the one who spoke for three hours.

With Items in a Series (“Serial Comma”) Use commas to separate items in a series. A series is a set of nouns, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, phrases, or clauses joined by commas and a final coordinating conjunction. The serial comma, before the coordinating conjunction at the end of a series, is often necessary to avoid confusion so most style guides recommend using it. Newspaper style, including that of The New York Times, often omits the serial comma.

With: Winston Churchill told the English people that he had nothing to offer them but blood, toil, sweat, and tears.

Without: Lincoln’s great address commended government of the people, by the people and for the people.

With Two or More Adjectives Use commas to separate two or more adjectives before a noun or a pronoun if you can use the conjunction and in place of the commas.

Lyndon Johnson flew a short, dangerous combat mission in the Pacific during World War II.

(Lyndon Johnson flew a short and dangerous combat mission in the Pacific during World War II)

With Direct Quotations Use a comma with quotation marks to set off a direct quotation from the clause that names the source of the quotation. When the source comes first, the comma goes before the quotation marks. When the quotation comes first, the comma goes before the last quotation mark.

She said, “I’m sorry, but all sections are full.”

“But I have to take the course to graduate,” he said.

Do not use a comma if the quotation ends in a question mark or an exclamation point.

“Do you believe in fate?” he asked.

“Believe in it!” she cried. “It has ruled my life.”

In some cases, a colon can precede a quotation. (See colons.)

Parenthetical Elements are words, phrases or clauses that add further description to the main statement the sentence makes. Always set such elements off by paired commas: i.e., a comma at the beginning of the element and another at the end.

Brian Wilson, however, was unable to cope with the pressures of touring with the Beach Boys.

Senator Cadwallader, responding to his campaign contributions from the coal industry, introduced a bill to begin strip-mining operations in Yellowstone National Park.

With Numbers, Names, and Dates Use a pair of commas to separate parts of place names and addresses.

At Cleveland, Ohio, the river sometimes catches fire.

Commas are used to separate the day from the year.

On October 17, 1989, the largest earthquake in America since 1906 shook San Francisco.

No comma is necessary when the day of the month is omitted.

Germany invaded Poland in September 1939.

Some writers use a form of the complete date that requires no comma at all.

She graduated from college on 5 June 1980.

Checklist: Avoiding Unnecessary Commas

A comma should not separate a subject from its verb or a verb from its object or complement unless a nonrestrictive clause or phrase intervenes.

A comma should not separate a subject from its verb or a verb from its object or complement unless a nonrestrictive clause or phrase intervenes.Incorrect:

The tulips that I planted last year, suddenly died.

Revised:

The tulips that I planted last year, which grew rapidly, suddenly died.

Do not separate prepositional phrases from what they modify. A prepositional phrase that serves as an adjective is not set off by commas from the noun or pronoun that it modifies.

Do not separate prepositional phrases from what they modify. A prepositional phrase that serves as an adjective is not set off by commas from the noun or pronoun that it modifies.Incorrect: The book, about terrorists, was simplistic.

A prepositional phrase that serves as an adverb is not set off from the rest of the sentence by commas.

A prepositional phrase that serves as an adverb is not set off from the rest of the sentence by commas.Incorrect: He swam, with the current, rather than against it.

Do not divide a compound verb with a comma.

Do not divide a compound verb with a comma.Incorrect: He ran, and walked 20 miles.

But if the parts of a compound verb form a series, set off the parts of the verb with commas.

But if the parts of a compound verb form a series, set off the parts of the verb with commas.He ran, walked, and crawled 20 miles.

Do not use a comma after the last item in a series unless the series concludes a clause or phrase set off by commas.

Do not use a comma after the last item in a series unless the series concludes a clause or phrase set off by commas.He loved books, flowers, and people and spent much of his time with all of them.

Three “scourges of modern life,” as Roberts calls the automobile, the telephone, and the polyester shirt, are now ubiquitous.

Avoid commas that create false parenthesis.

Avoid commas that create false parenthesis.Incorrect: A song called, “Faded Love,” made Bob Wills famous.

Semicolons

Semicolons are punctuation marks stronger than a comma, but weaker than a period. Use semicolons sparingly.

Use a semicolon to join independent clauses that are closely related in meaning. A coordinating conjunction or a conjunctive adverb may precede the semicolon.

Use a semicolon to join independent clauses that are closely related in meaning. A coordinating conjunction or a conjunctive adverb may precede the semicolon.Silence is deep as eternity; speech is shallow as time.

—Thomas Carlyle

In the first draft I had Bigger going smack to the electric chair; but I felt that two murders were enough for one novel.

—Richard Wright

In the first sentence above, the semicolon helps stress the relation between the two clauses. In the second sentence the semicolon emphasizes the connection between the two independent clauses.

Use a semicolon to join independent clauses separated by a conjunctive adverb, such as however, nevertheless, moreover, then and consequently. Conjunctive adverbs connect ideas between clauses, but these adverbs cannot work without appropriate punctuation. In these cases place a semicolon before the conjunctive adverb, and a comma after it.

Use a semicolon to join independent clauses separated by a conjunctive adverb, such as however, nevertheless, moreover, then and consequently. Conjunctive adverbs connect ideas between clauses, but these adverbs cannot work without appropriate punctuation. In these cases place a semicolon before the conjunctive adverb, and a comma after it.He had biked a hundred miles in ten hours; nevertheless, he now had to do a marathon.

Sheila had to wait at home until the plumber arrived to fix the water heater; consequently, she was late for the exam.

Use semicolons to separate various elements in a series when some of those elements contain commas.

Use semicolons to separate various elements in a series when some of those elements contain commas.They are aware of sunrise, noon and sunset; of the full moon and the new; of equinox and solstice; of spring and summer, autumn and winter.—Aldous Huxley

Use semicolons to separate elements that contain other marks of punctuation as well.

Use semicolons to separate elements that contain other marks of punctuation as well.The assignment will be to read Leviticus 21:1-20; Joshua 5:3-6; and Isaiah 55:1-10.

Apostrophes

Apostrophes form the possessive case of all nouns and of many pronouns. Apostrophes indicate omitted letters in words written as contractions. In only rare cases do apostrophes form plurals, so a good rule is not to use an apostrophe to make a word plural.

Forming a Possessive To form a possessive, add an apostrophe plus s to a noun or pronoun, whether it is singular or plural, unless the plural already ends in s; then add an apostrophe only.

Singular: a baby’s smile, the woman’s hat

Plural: the men’s club, the children’s books, everyone’s park, the robbers’ plans

Many writers add both an apostrophe and a final s to one-syllable singular nouns already ending in–s and to nouns of any number of syllables if the final s is a hard sound (as in kiss). The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage recommends this style as well.

Keats’s poetry, Ross’s flag, Elvis’s songs, the kiss’s power

However, other style manuals consider Keats’ poetry, Ross’ play, Elvis’ song, kiss’ power correct.

The Times suggests dropping the s after the apostrophe if a word ends in two sibilant sounds (ch, sh, j, s, or z) separated

only by a vowel sound: Kansas’ climate, the sizes’ range).

Sometimes the thing possessed precedes the possessor. Sometimes the sentence may not name the thing possessed, but the reader easily understands its identity. Sometimes both the of form and an apostrophe plus s or a personal possessive pronoun can indicate possession.

The motorcycle is the student’s.

Is the tractor Jan Stewart’s?

I saw your cousin at Nicki’s.

Other Common Uses of Apostrophes Proper names of some geographical locations and organizations do not take apostrophes, even though possession is implied.

Kings Point, St. Marks Place, Harpers Ferry, Department of Veterans Affairs

For hyphenated words and compound words and word groups, add an apostrophe plus s to the last word only. my father-in-law’s job, the editor-in-chief’s responsibilities Use apostrophes with concepts of duration and monetary value.

An hour’s wait, two minutes’ work

To express joint ownership by two or more people, use the possessive form for the last name only; to express individual ownership, use the possessive form for each name. McGraw-Hill’s catalog

Felicia and Elias’s house

Felicia’s and Elias’s houses

The city’s and the state’s finances

Showing omission In a contraction—a shortened word or group of words formed when some letters or sounds are omitted—the apostrophe serves as a substitute for omitted letters.

| it’s | (for it is or it has) |

| weren’t | (for were not) |

| here’s | (for here is) |

| comin’ | (for coming) |

| you’re | (for you are) |

Apostrophes can also substitute for omitted numbers: The ’50s were a decade of relative calm; the ’60s were much more turbulent. The New York Times uses the apostrophe in these dates (1960’s, 1970’s).

Special uses of apostrophes for plurals The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage suggests the use of an apostrophe to show the plural form of an abbreviation, a number or a letter:

two TV’s, the new Delta 747’s, mind your p’s and q’s

Many writers, however, omit the apostrophe in these cases.