CHAPTER

2

Fuelling the Heavenly Habit

The smell of boiling potatoes spilled into the narrow confines of the courtyards and alleys of Victoria’s Chinatown. The click of mah-jong tiles and fantan beads echoed past the hurrying footsteps of men who slipped through doorways and up wooden staircases. The smell, the sounds, the movement were all familiar to anyone who wandered into the half-dozen city blocks in the 1880s and for several decades thereafter. The smell was not in fact potatoes but the odour of smoking opium being produced from the sticky, dark brown balls of raw opium that arrived by ship from India. Smoking opium was much desired by the Chinese immigrants who had come here for the gold rush, for the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) or for many other jobs not as willingly or as cheaply done by European immigrants.

It was hard to hide the smell, especially since about 15 small factories were located in and around the area, each engaged in refining raw opium. But at that time there was no need to hide. Importing, refining, using and exporting opium were perfectly legal in Canada, provided that the importers paid the small duty on the raw substance when it entered the country.

The process of refining opium was sufficiently accepted in Canada for Lady Aberdeen, the wife of 1890s Governor General Lord Aberdeen, to visit an opium factory when she was in Victoria. She was fascinated by the procedure. “Our first visit was to Tai Yuen, an opium refiner. We were shown all the processes from the time it was brought in its raw state, made up into balls the size of the cocoa nut, covered with a mass of dried opium leaves. Then it is split open, put in pans and boiled and stirred and left to cool, and then boiled again.” The tarry mass was then packed into brass cans and soldered shut, each can containing about six and a half ounces (184 grams) of opium ready for smoking.

The ritual around smoking was precise: the user took a piece of the processed opium, pulled it and drew it about until it turned a lighter colour. Impaled on a needle, it was dropped into an opium pipe, held above a lamp flame and then inhaled as the drug bubbled in the bowl of the pipe, which was often handsomely decorated and marked with the maker’s name. As he (most opium smokers were male) drew in the fumes, he succumbed to his opium dreams. Literature abounds with descriptions of the dens of opium smokers and the gentle haze in which they lived.

In the 1880s, there were about 3,000 Chinese men living in British Columbia, most of them in Victoria. Separated from wives and family, they clung to some traditional habits, among them the smoking of opium. Yet far more opium was processed in Victoria than could be smoked by the city’s—or even the country’s—opium users. The rapid increase in opium processing was the result of changes in the law in the United States. As in Canada, the attitude to opium in the United States was ambivalent. In an era long before drug prohibition became popular, opium smoking was regarded as something routinely practised by Chinese and nothing to be concerned about. But, said legislators and moralists, it was a hideous trap for white people, especially for any white women caught in the vastly exaggerated “toils” of the opium seller and dragged down to the degenerate level of the opium user.

The American government, however, saw no reason to ban opium use outright, for it did not mind if its Chinese immigrants continued the practice. Instead, the government decided it should be regulated so the government would get its cut. In 1880, in an agreement with China, the United States forbade Chinese citizens from importing opium into the country; henceforth, only Americans would have that privilege. The opium imported at the time was refined by Chinese manufacturers. The United States further declared that only American citizens would be allowed to refine opium—and Chinese immigrants could not by law become American citizens. In addition, a $12 per pound duty was imposed on smoking opium legally imported into the country.

Chinese immigrants in the United States wanted opium and were willing to pay for it. Chinese who were in the business promptly moved north to Canada, most of them to Victoria, and those already in Victoria and New Westminster expanded their businesses. Within a few years, more than a dozen opium factories were at work in Victoria and a few in New Westminster. As Vancouver grew from its founding in 1886, its Chinatown also began to smell of boiling potatoes.

The duty levied on opium imports into Canada in 1881 was just $13,668. By 1887, it had quadrupled; by 1891, at its peak, opium brought $146,760 into government coffers, more than 10 times the amount from just 10 years earlier. The polite fiction existed that the factories were turning out opium for local consumption, but every Chinese person in Victoria would have had to smoke massive quantities day and night to consume what was being produced in Chinatown. Not long after the new American regulations went into effect, refined opium began to move in ever-increasing quantities between British Columbia and the United States.

By modern standards, the profit on smuggling refined opium was slim. Raw opium cost importers about $2.50 a pound, and the Canadian import duty of 25 percent brought the cost up to just over $3 per pound. The city of Victoria collected a licence fee from each opium factory, where Chinese were employed to refine the drug. With the cost of taxes, employees, transport to the United States, bribery of officials and shipments lost to zealous customs officials, thieves or other misfortunes, the cost of the refined opium probably reached somewhere between $7 and $10 a pound. It sold for $12 to $18 a pound to merchants in the United States.

Yet smuggling opium was profitable enough to keep the supply flowing south. Barely a week went by between 1880 and 1909 without newspaper reports about the seizure of smuggled opium. The amount seized and the smugglers charged represented just a small portion of the actual traffic. Thousands of pounds of smoking opium were carried illegally into the United States each year between 1880 and 1910.

Writing in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in 1891, Julian Ralph spent considerable verbiage on the smuggling of Chinese across the border. He saved a few words, however, to describe the smuggling of opium, which he suggested was much more profitable than the smuggling of Chinese. Canadians, he said, seemed not at all exercised by the practice because it involved breaking a neighbour’s laws and not their own. According to Ralph, it was a moral question, and “the Canadians, instead of taking the bull by the horns, allow the animal to roam unfettered.” He wrote:

There is scarcely a devisable manner of concealment of the little cans in which the opium is put up that is not practised in smuggling this item over our border. It comes in barrels of beer, in women’s bustles, in trunks, in satchels, under the loose shirts of sailors, in boatloads by night, in every conceivable way. By collusion with steamboat and steam-shop captains, and through corrupt officials in our own country, the greatest profits are made possible.

The King of Smugglers

Even for the tenor of the times, the words were overblown: Larry Kelly was termed desperate and notorious. Worse for those who believed in strict adherence to the law, he was frequently successful. For 40 years, Kelly, British by birth, Confederate soldier by choice, smuggler by trade, battled the revenuers. Sometimes he won and sometimes he lost, but he never left his calling.

Lawrence Kelly sailed into New Orleans aboard a British navy ship in the early days of the American Civil War. Presumably craving adventure, or perhaps just bored with routine shipboard life, he deserted and joined the Confederate Army. When the war ended, he headed westwards to the Puget Sound area. Some say he swore he’d never earn an honest living under the American flag; certainly, he never tried to.

No one knows when he started smuggling. He was first caught in 1872, bringing Canadian silks across the American border, and was fined $500. That mishap taught him that fines were just the cost of doing business as a smuggler. From that day on, he smuggled anything that promised to make him a profit, from furs to wool to Chinese to opium. Even though he was known as the King of the Smugglers, he was repeatedly arrested and fined or imprisoned, and his cargo confiscated by law officials. But he kept on at the only trade he knew.

Kelly lived in the San Juan Islands with his wife, whom he married when he was 32 and she was 16, putting his property in her name in the hopes it would keep it out of the hands of the law. Barrel-chested, short and broad like a fire plug, he looked rough and tough. His eyes met anyone’s gaze. When he was young, he sported a bushy beard, and he grew a floppy moustache when he was older. He had thick, uncombed brown hair that receded as he aged. As a young man, he was also described as wearing a dirty shirt and overalls, his feet bare and browned. A photograph of him when he was in his sixties shows him wearing suspenders and a wrinkled shirt. He had six children. Though he was never known to hurt a child and had no history of violence, his reputation frightened island children so much that, as one resident later noted, “Just the sound of his name . . . made us kids tremble with fear.”

Larry Kelly roamed the channels of the San Juan Islands in a fishing sloop until he knew every backwater and every passage. He slipped across the strait to Victoria to load up with illegal Chinese men to be delivered to the United States and then later took on opium, which he could sell at a tidy profit.

We only know about the smuggling trips that failed, the times that he was arrested, which were probably a small fraction of the trips he actually made. Customs agents were well aware of Kelly’s activities but generally unable to catch up with his swift boat or even find him as he slipped through the waters he knew so well. Agents suspected that he used Swinomish Slough, near La Conner, Washington, as a place to move opium onto the mainland. Agent Thomas Caine lay in wait for him there on December 21, 1882, but Kelly suspected a trap. He jumped overboard to swim and push his boat ahead of him. When Kelly appeared out of the darkness, Caine boomed out an order for him to surrender. He was caught with 40 cases of Chinese wine and a Chinese man but was fined just $150. The man was apparently an American resident, and the wine wasn’t taken too seriously.

By 1886, Kelly had bought property on a small island with a view over Juan de Fuca Strait toward Canadian waters. He loaded opium in Victoria, then slipped across to his home island, where he cached the drug until he deemed conditions right for transfer to his buyers in Seattle or Tacoma. Customs officers were always on the lookout for him. That same year, he was caught in Tacoma with some 300 pounds (136 kilograms) of opium on board, and his boat was confiscated. Yet his fine was a minuscule $100, and he was soon back at work.

Kelly had myriad ways of avoiding detection. He often sewed cans of opium into a sack and towed them along behind his boat, weighting the sack so that it stayed underwater, invisible to pursuers, or tying it to a float when docked, then retrieving it when the customs inspection was complete. Some said that he roped together the Chinese he was smuggling into the United States and tied them to a hunk of pig iron. If chased, he could sling them overboard, and they would sink and never be found. But that story was very probably apocryphal: Kelly said he had never done such a terrible thing, though he had landed Chinese on one side of an island with directions to walk to the other side for pickup, and on occasion, he had landed illegal immigrants back on Vancouver Island, swearing to them that they were in the United States.

“A Smuggler Captured,” trumpeted the New York Times in March 1891, describing Kelly’s apprehension near Tacoma. “Larry Kelly, one of the most desperate and successful smugglers on the coast, was arrested last night on board a train for Portland,” the paper reported. Deciding that he was too well known now to run his opium into Portland by boat, Kelly took the train. It was his bad luck that aboard that train was Charles Mulkey, a special agent from the Treasury Department, a man who would later figure in one of the most notorious opium conspiracies in the Pacific Northwest. Spotting the smuggler, Mulkey asked to see what Kelly had in his new satchel. “Clothes,” Kelly replied. “Open it up,” Mulkey demanded. Inside were 65 cans of opium.

“Larry was mad,” the Times declared. “He swore that no revenue officer would ever take him, but all the same the arrest was made, and in a few minutes the officers transferred their man . . . to the north-bound train for Tacoma.” Mulkey and a police officer hustled Kelly off the train and onto a neighbouring train northbound to Tacoma.

On trial, Kelly said Mulkey had planted the opium on him, but he was found guilty and sentenced to two years at McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary. The authorities weren’t through. While Kelly was in jail, they continued their investigation, commandeering his sloop and other property to pay his fines. When he emerged from jail, Kelly seemed to have changed for the worse. He confronted his wife, who was keeping house for another man to support herself, and threatened her with a gun. He frequently appeared drunk.

Suspected of stealing such things as 100 feet (30 metres) of cable, tools and five boxes of codfish to pay the remaining fines, he fled from law officials but was found the next day in a remote location, arrested and handcuffed. He jumped overboard, handcuffs and all, and escaped. A week later, a passerby saw two men at a camp on one of the islands and suspected they might be smugglers. When customs officers arrived, the camp was deserted but some $5,000 worth of opium remained. Was it Kelly’s? They weren’t sure.

They were sure that Kelly had bought another boat and were pretty sure that he was smuggling again. He was now almost 60 and a little slower on his feet and in his planning. In 1901, he arrived in Seattle from Victoria. He went off for an evening’s drinking but imbibed too much and was arrested for drunkenness. The Victoria police tipped off the Seattle police, who searched his room and found two suitcases full of illegal opium. Yet his lucky star still shone: the court fined him an amazingly low five dollars and let him keep the opium.

But Kelly’s luck was running out. That same year, he was arrested in Portland and sent to jail for two months for possession of $800 worth of illegal opium. In January 1905, customs inspector Fred Strickling boarded a train near the Canadian border, acting on a tip that Kelly would be on board. Somewhere down the line, Kelly climbed onto the train. Strickling asked to see inside Kelly’s valise. Kelly refused, shoved Strickling aside and leapt from the train. Stopping the train, Strickling found 65 tins of opium in Kelly’s bags, then had the engineer back the train up. Jumping off, he found his man unconscious and badly cut from his rough landing. He arrested Kelly, and took him to town, but Kelly promptly skipped out on his $1,000 bail.

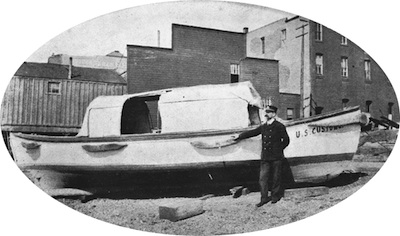

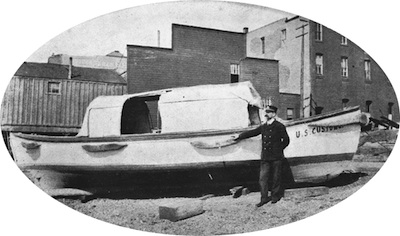

Larry Kelly was one of the most successful smugglers on the coast, a man who slid in and out of Puget Sound channels with his cargos of illegal Chinese and opium. Customs officer Fred Dean, above, and a fellow officer arrested Kelly for the last time in 1905, on his way from Victoria to Olympia, Washington, with a sloop-load of opium.

BC Archives C-06471

In July, he was arrested again, with a boatload of opium, by customs officials including Fred Dean. This time, he was sentenced to two years in prison. Released early for good behaviour, he was re-arrested for the earlier offence. In 1909, he was sentenced to a further year in jail.

He was 73 years old when he left prison in 1910 and, according to an article in the Atlanta Constitution, “broken in spirit and body by confinement . . . his strength is wasted, his nerve is gone and he is without a dollar . . . It is likely the veteran will pass the rest of his days in the poor house and rest in the potters’ field.”

Despite Kelly’s age and failing health, the paper further said he would be followed by customs officials to the day he died. “Measured by the law’s standard he is a criminal, but he is whole-souled and generous, ready and willing to divide his last dollar with an unfortunate. He has never implicated others, and he has the reputation of being ‘square’ with those who profited by his traffic, though he had an opportunity to fleece them whenever he brought a sloop load of contraband goods into the country.”

Kelly, said the writer, was a fine mariner and could have made a living on the sea by more reputable means. But smuggling appealed to him as a game of chance, where he could outwit the customs officers by finding a loophole in their “carefully drawn picket lines.” Far from being a man of violence, he declared, Kelly had never fired a shot or harmed a single person, a fitting epitaph for the man they called the King of Smugglers.

Kelly found a bed at a Confederate soldiers’ home in Louisiana. He died there around 1911.