Chapter 8

The World of the Child

Understandably, children and adults contended with the persecutory policies of the Nazi period in markedly different ways. Child victims and survivors of genocide were, after all, still children. This chapter reflects the events of the Shoah, or Holocaust, through their eyes and explores the ways in which youngsters coped with the menacing world in which they found themselves.

Learning and play are two elemental activities associated with childhood. During the Holocaust, children used both to adapt to their difficult circumstances and to restore a sense of normalcy to their disordered lives. In many ghettos throughout eastern Europe, Nazi authorities forbade formal educational instruction for Jewish children. Yet, thousands of school-age children defied such bans by attending a network of clandestine schools organized by education and welfare agencies in many ghetto communities. For young people, such secret study was a means of transcending the narrow walls of the ghetto and fulfilling important intellectual and emotional needs. Teenagers also took pleasure in participating in extracurricular educational and cultural events, such as literary circles, exhibitions, and musical recitals, which offered an important conduit for creativity and artistic collaboration within a captive community.

Play provided children with another powerful outlet to give the terrifying world about them safer contours. Entering a realm of daydream and imagination allowed youngsters to escape their harrowing and uncertain existence and eschew the fear and hunger that tormented them. With a creativity and ingenuity that surprised adult observers, youngsters invented new toys and games with the very limited resources available to them. Often children incorporated the macabre realities of their camp or ghetto surroundings. Integrating the horrors and tragedies that they witnessed into their play may have helped young children to absorb and assimilate the traumatic events that punctuated their everyday existence.

Like learning and play, innocence is another element closely associated with childhood. But were children in Nazi camps and ghettos innocent of the dangers that awaited them? Could children comprehend the malignant forces that they faced? Documentation concerning innocence and knowledge examines the degree to which children lived aware or unaware of their perilous circumstances. In most cases, youngsters matured quickly, gaining experience beyond their years, witnessing unimaginable horrors, and shouldering grown-up responsibilities. With a flexibility that many adults lacked, children often found highly creative ways to cope with the difficulties they confronted. Through imagination, play, and their dreams for the future, young people managed to transcend the physical and emotional traumas they experienced and cling to their hopes for survival.

Escape into Learning

Learning is an essential and indispensable feature of childhood, the school years being part of a youngster’s evolution to adulthood. Yet, during the war years in German-occupied Europe, a majority of Jewish children were denied the possibility of a formal education. In November 1939, just weeks after the Polish army capitulated, German officials in the General Government banned Jewish children from all public and private schools. In the Polish capital alone, forty thousand Jewish youngsters of school age were barred from attending classes.1 With very few exceptions, as in the case of the Łódź ghetto, which boasted an impressive array of officially sanctioned educational institutions,2 prohibitions or severe restrictions upon formal instruction for Jewish children remained in effect when Jewish populations were ghettoized in Poland and other German-occupied territories in eastern Europe. When the largest of these communities, the Warsaw ghetto, was enclosed in November 1940, German authorities imposed a ban on the establishment of schools, citing the threat of contagion. Only a select number of vocational-training courses were permitted in August 1940, and only in September 1941 did German officials countenance the opening of a number of elementary schools for ghetto pupils.3

1. Barbara Engelking and Jacek Leociak, The Warsaw Ghetto: A Guide to a Perished City, trans. Emma Harris (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 343.

According to available statistics, some 48,207 school-age children between the ages of seven and fourteen lived in the Warsaw ghetto4; to this figure we must add thousands of adolescents who, under normal circumstances, would have attended secondary or college-preparatory schools (Gymnasia). Yet, only a small fraction of their number had access to formal instruction. In such a setting, how was it possible to provide an education to the youth of the Warsaw ghetto? Clearly, a certain number of children were educated within their own homes, by parents, older siblings, or relatives. Several thousand orphaned or severely disadvantaged youths who lived in CENTOS homes or orphanages presumably also received at least limited informal instruction from caregivers. Yet, already in the summer and autumn of 1940, representatives of Jewish educational and welfare organizations had begun working to construct a network of clandestine schools for youngsters and adolescents. Many underground classrooms gathered in soup kitchens and care institutions for young people. In these instances, instructors and administrators pursued the dual goal of feeding hungry children and providing them a basic educational foundation. Other less formally organized “schools” met secretly in the private homes of instructors or their pupils. From the autumn of 1940 until the summer of 1942, a wide range of underground centers offered educational instruction to ghetto youths. In addition to kindergartens and elementary schools, there existed a number of high schools, Gymnasia, vocational-training institutions, and cheder schools for religious instruction.

4. Engelking-Boni, “Childhood in the Warsaw Ghetto,” 34.

Clandestine classes for very young children incorporated lessons through stories, songs, and games. Parents and educators often described such gatherings as “play groups” in order to conceal covert learning activities and to prevent youngsters from inadvertently revealing their illicit schooling to others. Teachers stressed the importance of Beschäftigung (engagement in useful activity) as a way to combat boredom and delinquency among young children and to prepare them for the proficiency necessary from primary education.5 For elementary school children, educators stressed reading and writing, fearing that such skill sets might be lost to a generation of Jewish youth. For older children, clandestine Gymnasia and secondary schools also thrived in ghetto communities. The first underground Gymnasium in Warsaw, established under the auspices of the Dror youth organization, sheltered seventy-two pupils in its first year and employed as its teachers intellectuals such as the famed Jewish writer Isaac Katzenelson.6 Because many instructors and sponsoring organizations were Zionist in political orientation, curricula often stressed Judaic and Zionist themes and offered theoretical and practical preparation for a new Jewish future in Palestine. Covert secondary schools in the ghetto maintained high standards, devising enrollment criteria for prospective pupils, offering advanced courses in literature, the arts, and the sciences, and issuing degrees. As secrecy was an important issue, students did not receive certificates on graduation; examination records were preserved in hiding and legitimized by a special education commission after the war.7

5. See Lisa Anne Plante, “Transition and Resistance: Schooling Efforts for Jewish Children and Youth in Hiding, Ghettos, and Camps,” in Children and the Holocaust: Symposium Presentations of the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies (Washington, DC: U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2004), 45ff.

6. Engelking and Leociak, The Warsaw Ghetto, 346. Isaac Katzenelson (1886–1944) was born in Korelichi in Belorussia (now Belarus) and moved to Warsaw as a small boy. For many years he directed a Hebrew-Polish school in Łódź; writing in Hebrew, he produced many well-received plays, including The Prophet and The White Life. When German forces invaded Poland, Katzenelson began to write his works in Yiddish. In November 1939, he fled to Warsaw, where he was active as a writer and educator until 1943. In April 1943, during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Katzenelson escaped and succeeded in making his way to France on false papers; he was interned, however, in the Vittel detention camp and in 1944 deported to Auschwitz, where he perished. After the war his manuscript titled The Song of the Slaughtered Jewish People was discovered at Vittel and published in several languages.

7. Engelking and Leociak, The Warsaw Ghetto, 349.

According to calculations made by chroniclers of the Oneg Shabbat archive, some ten thousand children and adolescents attended clandestine classes in the Warsaw ghetto between 1940 and 1942.8 One of those students was fifteen-year-old Miriam Wattenberg, whose family had fled Łódź in late 1939. Mary’s mother was an American citizen, a connection that provided some security to Mary and her fellow pupils who engaged in a series of Gymnasium-level courses in the Wattenberg home.9 In her diary/memoir, published in February 1945, Wattenberg described how the clandestine nature of the instruction inspired a “strange earnestness” in pursuing an education among like-minded teachers and classmates.

8. Engelking and Leociak, The Warsaw Ghetto, 344.

9. Miriam Wattenberg was born in Łódź on October 10, 1924. She began a wartime diary in October 1939; in November 1940, Miriam, with her parents and younger sister, was compelled to live in the Warsaw ghetto. The Wattenbergs held a privileged position there because Miriam’s mother, Lena Wattenberg, was an American citizen. On July 17, 1942, shortly before the first large deportation of Warsaw Jews to Treblinka, German authorities detained the Wattenbergs and other residents with foreign passports in Warsaw’s infamous Pawiak Prison. In January 1943, the family was transferred to the Vittel internment camp, then one year later was allowed to emigrate to the United States. Wattenberg’s diary was published in English in February 1945, three months before the end of World War II in Europe; to protect friends and relatives still in Nazi hands, the author employed the pen name “Mary Berg.” The resulting volume, The Diary of Mary Berg, was one of the very few eyewitness accounts of the Warsaw ghetto available to American audiences before the end of World War II. See Susan Lee Pentlin, ed., The Diary of Mary Berg: Growing Up in the Warsaw Ghetto, ed. S. L. Shneiderman, trans. Norbert Guterman and Sylvia Glass (Oxford: Oneworld Publishers, 2006).

Document 8-1. Diary/memoir of Miriam Wattenberg, entry for July 12, 1940, in Mary Berg, Warsaw Ghetto: A Diary by Mary Berg, ed. S. L. Shneiderman, trans. Norbert Guterman and Sylvia Glass (New York: L. B. Fischer, 1945), 32–33.

There are now a great number of illegal schools, and they are multiplying every day. People are studying in attics and cellars, and every subject is included in the curriculum, even Latin and Greek. Two such schools were discovered by the Germans some time in June [1940]; later we heard that the teachers were shot on the spot, and that the pupils had been sent to a concentration camp near Lublin.

Our Łódź Gymnasium too has started its classes.10 The majority of the teachers are in Warsaw, and twice a week the courses are given at our home, which is a relatively safe spot because of my mother’s American citizenship. We study all the regular subjects, and have even organized a chemical and physics laboratory using glasses and pots from our kitchen, instead of test tubes and retorts.11 Special attention is paid to the study of foreign languages, chiefly English and Hebrew. Our discussions of Polish literature have a peculiarly passionate character. The teachers try to show that the great Polish poets Mickiewicz, Slowacki, and Wyspianski prophesied the present disaster. [. . .]

10. Many of Mary Wattenberg’s classmates and teachers from Łódź had also gone to Warsaw. A portion of this class now reassembled for clandestine schooling in Mary’s house.

11. These are vessels often used in chemistry to distill or decompose substances over heat.

The teachers put their whole heart and soul into their teaching, and all the pupils study with exemplary diligence. There are no bad pupils. The illegal character of the teaching, the danger that threatens us every minute, fills us all with a strange earnestness. The old distance between teachers and pupils has vanished, we feel like comrades-in-arms responsible to each other.

For Warsaw ghetto teenager Pola Rotszyld, meeting with her clandestine study group gave her a sense of identity and purpose. “From this moment the most beautiful period of my life began,” she later recalled, “which lasted for more than a year. It was a time when I was really alive. I knew why and what I lived for.”12

12. Pola Rotszyld, quoted in Engelking-Boni, Childhood in the Warsaw Ghetto, 35. Born in 1926, Rotszyld survived the Warsaw ghetto and the final deportations and emigrated to Palestine in 1945.

Teenagers like Pola came to feel that emotional and intellectual survival was integral to their physical survival. Clandestine learning provided a sense of fellowship and camaraderie, which had evaporated elsewhere among a desperate community, and allowed young students, at least temporarily, to transcend the deprivation and misery of ghetto life. Such secret study was quite literally an escape into learning. For sixteen-year-old Pola and her circle of fellow pupils,13 these clandestine classes represented a central and transforming experience, as she recounted in 1945.

13. This circle included Andzia Adler, Luba Bursztyn, Sara Fajfer, Estera Gutgold, Dorka Jelén, Henia Majzlic, Gucia Rozenstrauch, and Guta Wołowicz. With the exception of Pola Rotszyld, none of these young girls survived the Holocaust. See Engelking-Boni, Childhood in the Warsaw Ghetto, 34–35.

Document 8-2. Diary entry of Pola Rotszyld (Yad Vashem Archives, sign. 03/438) in Barbara Engelking-Boni, “Childhood in the Warsaw Ghetto,” in Children and the Holocaust: Symposium Presentations of the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies (Washington DC: USHMM, 2004), 35.

These lessons were our happiness, our oblivion. Outside there was a warstorm[;] the groans of people dying of hunger, and the animal-like screams of Germans beating up people on the street were heard. And somewhere in the corner of the room on Pawia or Nowolipki Street, some girls between thirteen to fifteen years of age were sitting around the table with a teacher, engaged in studying. They all forgot about the whole world, even about the fact that they were a bit hungry, maybe more than a bit.

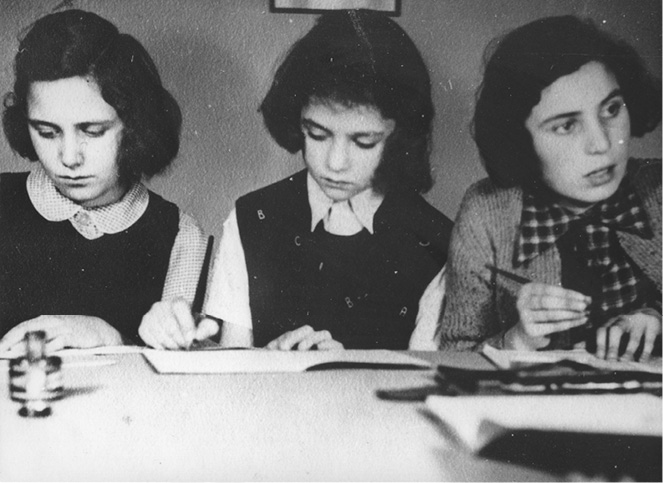

Document 8-3. Three girls study at a clandestine Jewish school in Prague, c. 1942, USHMMPA WS# 37424, courtesy of the Jewish Museum of Prague Photo Archive.

Particularly for older children and adolescents, the chance to engage in educational and cultural activities was a means to regain the normal opportunities of intellectual enrichment and advancement available to most school-age youths but inaccessible to those living within the finite borders of the ghetto. In many ghettoized communities, child-welfare associations attempted to provide youngsters with academic and vocational training, as well as a variety of organized educational and leisure activities. Sometimes, too, the impetus for creative and cultural endeavors sprang from young people themselves.

Yitskhok Rudashevski lived in the Vilna ghetto from the time of its inception until its final liquidation in the autumn of 1943. His father was a typesetter for Vilna’s most prominent prewar Yiddish daily newspaper, Vilner Tog, and from a young age, young Yitskhok showed a pronounced gift for writing. In September 1941, when he and his family were forced to settle in Vilna’s newly established ghetto, the fourteen-year-old began to keep a diary.14 The teenager filled his journal with vignettes of ghetto life, penning sketches of its teeming streets and its diverse and colorful inhabitants. Yet, the young man’s chronicle focused primarily on his own efforts and those of like-minded individuals to forge an intellectual life for the youth of the Vilna ghetto. In addition to his studies, at which he excelled, Rudashevski dedicated himself to the activities of two youth organizations, the first of which endeavored to compile a history of the ghetto and its residents in order to leave a record for future generations. The second club collected ghetto folklore: its stories and tall tales, jokes and curses, songs and literature. “Our youth works and does not perish,”15 Rudashevski wrote on October 22, 1942, suggesting that his activities and those of his colleagues represented a means to transcend the narrow limitations of their confinement and to defy both the physical and spiritual repression that persecution embodied. For the young Rudashevski, efforts such as those to create an exhibition honoring the Yiddish poet Yehoash16 provided a way to escape the moral and material barrenness of the ghetto and to create a space and time in which beauty and enlightenment could continue to exist.17

14. See Yitskhok Rudashevski’s description of his family’s relocation to the Vilna ghetto in Document 4-1.

15. Yitskhok Rudashevski, quoted in Alexandra Zapruder, ed., Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002), 192.

16. This is the pen name of Lithuanian-born Solomon Blumgarten (1870–1927), one of the most celebrated Yiddish poets of the early twentieth century. Immigrating to the United States in 1890, Blumgarten was responsible for translating many of the classics of world literature into Yiddish; his two-volume translation of the Bible is widely regarded as one of the great masterpieces in that language.

17. Yitskhok Rudashevski was shot to death with members of his family in the Ponary Woods in October 1943, during the dissolution of the Vilna ghetto.

Document 8-4. Diary of Yitskhok Rudashevski, Vilna ghetto, entry for March 14, 1943, in Alexandra Zapruder, ed., Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002), 223.

Today the Yehoash celebration as well as the opening of the Yehoash exhibition took place in the club. The exhibition is exceptionally beautiful. The entire reading room in the club is filled with material. The room is bright and clean. It is a delight to come into it. We are indebted for the exhibition to Friend Sutzkever, who smuggled into the ghetto from the YIVO where he works a great deal of material for the Yehoash exhibition. [. . .]

People entering here forgot that this is the ghetto. Here in the Yehoash exhibition we have many valuable documents that now are treasures: manuscripts from Peretz to Yehoash, Yehoash’s original letters. We have rare newspaper clippings. In the section—Bible translations into Yiddish—we have old Bible translations into Yiddish from the seventeenth century. Looking at the exhibition, at our work, our hearts swell with enthusiasm. We actually forget that we are in a dark ghetto. The celebration today was also carried out in a grand manner. The dramatic circle presented Yehoash’s tableau Saul. The members read essays on the writings of Yehoash, on Yehoash the poet, on beauty, sound, and color.

The mood of the celebration was an exalted one. It was indeed a holiday, a demonstration on behalf of Yiddish literature and culture.

At Play during the Holocaust

The juxtaposition of child’s play with the tragic events of the Holocaust presents the reader with a striking contradiction. Popular imagination associates play with the carefree world of merriment and simple delights. Instinctively, we balk at the suggestion that mass murder and the games and amusements of youth could exist side by side. And yet, scores of contemporary documents and the vivid recollections of survivors and bystanders make it plain that they did.18

18. See George Eisen, Children and Play in the Holocaust: Games among the Shadows (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988); Yad Vashem, No Child’s Play (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2004).

What can account for the existence of such activities in the midst of such catastrophic circumstances—in the desolate streets of the ghetto, in the bleak and dangerous world of the concentration camp? The most logical explanation for such a phenomenon is that play in every place and time is an instinct of childhood. Child survivor Nechama Tec recalled that her stay in the Majdan Tatarski ghetto in Lublin in 1942, though fraught with danger, was a happy time for her, for after a long period of isolation, she at last had the opportunity to play with other children.

The children formed a small minority. As a matter of policy, the Nazis were concentrating on the extermination of Jewish children. Because we were thus in special danger, adults looked upon us as a special commodity. We came to expect our elders to treat us with special indulgence, and they did. No Jew would have thought of mistreating a child, and almost all of them refrained from even the mildest form of discipline.

And so we were free of adult supervision. We had no special duties. It was summer. Because there were few of us left, we felt close to each other. We relied on each other for entertainment, and for enlightenment. [. . .] We children managed to be happy as we roamed the little dirt roads in search of adventure. We spent our days outdoors, constantly on the move. In the evenings we took turns visiting each other’s houses. In the process, we made many exciting adventures about life, love, and our fellow mortals.19

19. Nechama Tec, Dry Tears: The Story of a Lost Childhood (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982), 22–23.

To run and frolic with their playmates, to act out their fantasies, and to explore the world about them gave children a powerful way to escape the harsh realities that surrounded them. Play also represented a way for youngsters to adapt to the difficulties and traumatic circumstances they confronted and to reshape their environment through daydream and imagination. As in the pre-Holocaust world, children also used such activities in order to develop needed skill sets and to socialize themselves for future mature roles and responsibilities.20

20. See Catherine Wheeler, Representing Children at Play in the Literature of the Shoah (PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 2003).

Document 8-5. Children at play in a field in Marysin, Łód´z ghetto, c. 1941, USHMMPA WS# 33844, courtesy of the Archiwum Panstowe w Łód´zi, sygn. 1120, fot. 27-832-6.

For many adults, the sight of children at play in the camp barracks or among the rubble of the ghetto alley was a heartening sight. While the misery and deprivation of their surroundings told a story of destruction and loss, child’s play prefigured life, continuity, and collective survival. One such encouraged individual was Oskar Rosenfeld (1884–1944),21 a Czech-born writer and novelist who had been active in Vienna until the Anschluss. Deported to the Łódź ghetto from Prague in November 1941, Rosenfeld soon numbered among the authors who contributed essays and commentaries for The Chronicle of the Łódź Ghetto,22 an effort to document the history of the incarcerated community. In July 1943, Rosenfeld captured ghetto youngsters’ enduring love of play and pastimes in an essay for the official chronicle titled “The Ghetto Children’s Toys.” A month later, Rosenfeld took up this theme again, announcing to his readers that the children of the Łódź ghetto had invented a new plaything.

21. Living in Vienna in the interwar period, Moravian-born Oskar Rosenfeld worked as a journalist and author, publishing a series of novels under the title Tage und Nächte (Days and Nights); from 1929 he was the editor in chief of the Viennese illustrated weekly Die Neue Welt (The New World). Following the Anschluss, Rosenfeld and his wife moved to Prague. Unable to emigrate to England, the couple was deported to the Łódź ghetto in November 1941, where Rosenfeld became active in writing for The Chronicle of the Łódź Ghetto. Upon the liquidation of the ghetto, Rosenfeld was deported to Auschwitz in August 1944, where he perished. See Oskar Rosenfeld, In the Beginning There Was the Ghetto: Notebooks of Łódź (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2002).

22. Lucjan Dobroszycki, ed., The Chronicle of the Łódź Ghetto, 1941–1944, trans. Richard Lourie et al. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987).

Document 8-6. Oskar Rosenfeld, entry in The Chronicle of the Łód´z Ghetto, August 25, 1943, in Lucjan Dobroszycki, ed., The Chronicle of the Łód´z Ghetto, 1941–1944, trans. Richard Lourie et al. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987), 373–74.

For several days now, the streets and courtyards of the ghetto have been filled with a noise like the clatter of wooden shoes. The noise is disturbing at first, but one gradually gets used to it and says to oneself: this is as much a part of the ghetto as are cesspools. The observer soon discovers that this “clattering” is produced by boys who have invented a pastime, an entertainment. More precisely, the children of the ghetto have invented a new toy.

All the various amusing toys and noisemakers—harmonicas, hobby horses, rattles, building blocks, decals, etc.—are things our youngsters must, of course, do without. In other ways as well, as ghetto dwellers, they are excluded from all the enchantments of the child’s world. And so, on their own, they invent toys to replace all the things that delight children everywhere and are unavailable here.

The ghetto toy in the summer of 1943: two small slabs of wood—hardwood if possible! One slab is held between the forefinger and the middle finger, the other between the middle finger and the ring finger. The little finger presses against the other fingers, squeezing them so hard that the slabs are rigidly fixed in position and can thus be struck against one another by means of a skillful motion. The resulting noise resembles the clattering of storks or, to use musical terms, the clicking of castanets. The harder the wood, the more piercing and precise the clicking, the more successful the toy, and the greater the enjoyment. Naturally, the artistic talents of the toy carver and performer can be refined to a very high level.

The instrument imposes no limit on the individual’s musical ability. There are children who are content to use the primitive clicking of the slabs to produce something like the sounds of a Morse code transmitter. Other children imitate the beating of a drum, improvising marches out of banging sounds as they parade with their playmates like soldiers.

The streets of the Litzmannstadt ghetto are filled with clicking, drumming, banging. . . . Barefoot boys scurry past you, performing their music right under your nose, with great earnestness, as though their lives depended on it. Here the musical instinct of eastern European Jews is cultivated to the full. An area that has given the world so many musicians, chiefly violinists—just think of Hubermann, Heifetz, Elman, Milstein, Menuhin23—now presents a new line of artists.

23. All are famous contemporary Jewish violinists.

A conversation with a virtuoso: “We get the wood from the Wood Works Department, but only the hardest wood is good enough.”—“What is the toy called?”—“It’s called a castanet. . . . I don’t know why. Never heard the name before. We paint the toy to make it look nicer. That guy over there,” he pointed to a barefoot boy who was sitting in the street dust, ragged and dirty, “doesn’t know how to do it. You have to swing your whole hand if you want to get a good tune out. Hard wood and a hefty swing—those are the main things.” A few boys gathered, clicked their castanets, and all hell let loose. It was the first castanet concert I had ever attended.

The chronicler assumes that the clicker music will vanish “after it’s run its course” and be replaced by some other sort of music. But he may be wrong.

O[skar] R[osenfeld]

Youngsters in camp and ghetto settings lived in a kind of exile from childhood. With the loss of their homes and belongings, young children felt the absence of their favorite playthings acutely. With forced ghettoization, families brought to their cramped quarters only what they could carry; personal items, among them children’s toys and games, were necessarily limited. Possession of material goods became even more severely circumscribed with an individual’s transfer to concentration and forced labor camps, and where young children survived in these circumstances, as in the so-called Theresienstadt family camp in Auschwitz, playthings were a rare commodity. With a creativity and ingenuity that often impressed their adult contemporaries, young people forged new toys from cardboard, bits of wood, scraps of metal and cloth—the refuse of the captive society that surrounded them. Children played with what was at hand. When her interviewer expressed incredulity that she had been able to entertain herself at Auschwitz, a young survivor from Kielce exclaimed adamantly, “But I played! I played there with nothing! With the snow. With balls of snow.”24

24. Quoted in Eisen, Children and Play in the Holocaust, 72.

For those children fortunate enough to retain a cherished toy or childhood possession, a doll or stuffed animal might figure as the center of the youngster’s existence. Playthings were rare and precious, and their young owners often clung to them with a fierce possessiveness. Such toys offered not only an opportunity for amusement but also a source of emotional stability and security. In a menacing world of upheaval and change, material items remained steadfast and unchanging. Toys were good listeners in the way that harried and exhausted adults were not. Even broken and damaged playthings retained their currency; they did not wither away from hunger or face deportation as parents or siblings did. A toy might also transport its small owner into an imaginary world, far away from the miserable surroundings of the camp or ghetto.

In the formative years of the Theresienstadt ghetto, a prisoner employed as a carpenter in a joiner’s workshop in the Small Fortress created the remarkable pull toy in the shape of a butterfly shown in Document 8-7. Affixed to a wheeled base, the brightly painted butterfly “takes flight,” fluttering its wooden wings, when it is rolled across a floor or flat surface. The butterfly motif has long been associated with the children of Theresienstadt, thanks largely to the discovery and widespread publication of Pavel Friedman’s poem “I Never Saw Another Butterfly,” written shortly after the young man’s arrival in the Theresienstadt ghetto in April 1942. Friedman died at age twenty-three in the gas chambers at Birkenau in late September 1944, but his poem is one of the most famous in the genre of Holocaust poetry:

The last, the very last,

So richly, brightly, dazzlingly yellow.

Perhaps if the sun’s tears sing

against a white stone [. . .]

For seven weeks I’ve lived in here,

Penned up inside this ghetto,

But I have found my people here.

The dandelions call to me,

And the white chestnut candles in the court.

Only I never saw another butterfly.

That butterfly was the last one.

Butterflies don’t live here in the ghetto.25

25. Pavel Friedman, “I Never Saw Another Butterfly,” in I Never Saw Another Butterfly: Children’s Drawings and Poems from Terezin Concentration Camp, 1942–44, ed. Hana Volavková, exp. 2nd ed. (New York: Schocken Books and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, 1993), 39.

The butterfly was an evocative symbol not only because it represented an element of natural beauty long inaccessible to Theresienstadt’s incarcerated community but also because the winged creature had the ability literally to transcend the confining walls of the ghetto and to escape the barrenness and despair of the prisoners’ existence. Of course, the craftsman who constructed the pull toy in question is unlikely to have been aware of Friedman’s poem, and it is doubtful that a concrete connection lies between the artifact and the young writer’s famous verse. The maker of the small wooden toy is unknown, as are the identity and fate of its young recipient. But the object is a poignant reminder of children’s need for the tangible vestiges of childhood in the harrowing world of the Holocaust.

Document 8-7. Painted wooden butterfly toy, Small Fortress, Theresienstadt ghetto, 1941–1945, USHMMPA WS# N00049, original reposited in Pamatnik Terezin Narodni Kulturni Pamatka.

As we have seen, children often invented new modes of play in order to accommodate their difficult circumstances and the limited resources available to them. Sometimes, too, youngsters adapted traditional children’s games to incorporate their radically altered environment.26 To the horror of many adult witnesses, who had experienced normal childhoods, youngsters modified such conventional children’s games as tag and hide-and-seek with the macabre trappings of their camp or ghetto existence. At the 1961 Eichmann Trial, Dr. Aharon Peretz, a physician who survived the Kovno ghetto, recounted how the play of ghetto children came to reflect the frightening reality of the Holocaust.

26. See Eisen, Children and Play in the Holocaust, esp. 76–80.

Document 8-8. Testimony of Dr. Aharon Peretz, May 4, 1961, in The Trial of Adolf Eichmann: Record of Proceedings in the District Court of Jerusalem (Jerusalem: Trust for the Publication of the Proceedings of the Eichmann Trial in cooperation with the Israel State Archives and Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority, 1992–1995), 1:478–79.

Witness Peretz: I think that possibly the greatest tragedy the Jewish people underwent was the tragedy of the children. The children in the ghetto also used to play and laugh, and in their games the tragedy of the Jewish people was reflected. They used to play at graves, they would dig a pit, place a child in it, and call him Hitler. They used to play as if they were at the gate of the ghetto, some would be Germans and others Jews. The Germans would shout and strike the Jews. They used to play at funerals, and all such games.

Children’s “new” games accurately depicted the dramas and tragedies of ghetto life. Many Jewish youngsters had never known a park or a playground, had never owned a doll or stuffed animal, had never frolicked amid trees and flowery meadows. Thus, they constructed their make-believe worlds from the only existence they knew. Starvation and deprivation were a part of their quotidian lives. Words from the ghetto vernacular, such as Aktion, “deportation,” and “transport,” became a part of their daily vocabulary. While play that incorporated camp or ghetto life was unconventional and shocked adult observers, such activities presumably helped young children to process the perplexing circumstances in which they found themselves and offered them a kind of “buffered learning,” as George Eisen suggests—a way to rehearse a dangerous situation within a secure sphere, as within the parameters of a game or play activity.27 Into their imaginary world, children integrated the cruelty, irony, and pathos that they observed around them. In personal testimony given in the 1960s, Hanna Hoffmann-Fischel, a young and idealistic educator, recalled the unsettling games played by her young charges at the Theresienstadt family camp in Birkenau.

27. Eisen, Children and Play in the Holocaust, 79.

Document 8-9. Personal testimony of Hanna Hoffmann-Fischel, c. 1960, in Inge Deutschkron, Denn ihrer war die Hölle: Kinder in Gettos und Lagern (Cologne: Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, 1965), 52–55 (translated from the German).

Even in the next block, with the smaller children, we had enormous difficulties. We could not teach them according to a lesson plan, but we told them of the kind of life that we wished for ourselves. But if we were not careful, they played the kind of life’s games that they had experienced themselves. They played “Camp Elder and Block Elder,” “Roll Call,” with “caps off!”28 They played the ailing prisoners who would faint during roll call and receive a thrashing, or the “Doctor” who took away patients’ rations and who refused to give treatment if they could not give him anything in return. Once they even played the game “Gas Chamber.” They made a trench into which they pushed in one stone after another. These were supposed to be people who went into the crematorium, and they imitated their cries. They came to me for advice, asking me to show them where they should put the crematorium chimney.

28. In German, “Mützen ab!” is the command SS guards inevitably gave prisoners at roll call.

Children’s games incorporated the harrowing reality of the camp or ghetto environment. This kind of play was not an escape into fantasy or imagination but a way of assimilating the dangerous world that surrounded youngsters during the Holocaust. Role-playing in particular represented a creative means of accommodating and coping with the tremendous challenges youngsters confronted. Naturally, such play grew in part from children’s natural impulse to emulate the actions of adults. As in the normal realm of childhood, the enactment of adult behaviors often followed gender lines. Predictably, as in other places and times, young boys’ play frequently took the shape of war games. Ghetto lads of six or seven engaged in make-believe combat as Germans and Russians or pretended to join in the adventures of the partisans of whom they had heard so much. Closer to their own experience, preteenage boys in Vilna or Warsaw played “Going through the Gate” in which young “Gestapo men” searched returning “forced laborers” for smuggled food and contraband.29 Girls could and did participate in such games, but their play more often embraced female roles in the ghetto. Small girls who had perhaps once nursed their dolls now imitated their mothers in an eerily realistic form of playing house. Standing in queues before an imaginary shop window, little girls clutched make-believe ration cards, jostling their neighbors and bickering with the shopkeeper over goods and wares. The young housewives could be heard to wonder aloud where their next piece of bread would come from or how, with their few rotten potatoes, they might manage to feed their families.30

29. Testimony of Dr. Aharon Peretz, May 4, 1961, in The Trial of Adolf Eichmann: Record of Proceedings in the District Court of Jerusalem (Jerusalem: Trust for the Publication of the Proceedings of the Eichmann Trial in cooperation with the Israel State Archives and Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority, 1992–1995), 1:478.

30. Eisen, Children and Play in the Holocaust, 77.

One activity that perhaps best exemplifies the tragedy of Jews during the Holocaust was a favorite of both genders. The game “Jews and Germans” wed aspects of cops and robbers with the traditional hide-and-seek. In Document 8-10, an eight-year-old inhabitant of the Vilna ghetto explains how youngsters masqueraded as members of the Schutzstaffel (SS) or Jewish Order Police and sought to round up their playmates for deportation. Document 8-11, a photograph capturing children at play in the Łódź ghetto, illustrates that the game Jews and Germans was popular in almost every ghetto in German-occupied eastern Europe.

Document 8-10. An eight-year-old resident of the Vilna ghetto describes the game “Jews and Germans” (Genia Silkes Collection, YIVO Institute), quoted in George Eisen, Children and Play in the Holocaust: Games among the Shadows (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), 72.

Part of the children became “policemen” and part “German.” The third group was comprised of “Jews” who were to hide in make-believe bunkers; that is under chairs, tables, in barrels and garbage cans. The highest distinction went to the child who played Kommandant [Kittel], the head of the Gestapo [sic].31 He was always the strongest boy or girl. If a dressed-up “policeman” happened to find “Jewish” children, he handed them over to the “Germans.”

31. Oberscharführer Bruno Kittel, a member of the Security Police, was later responsible for the liquidation of Vilna ghetto.

Document 8-11. In the Łód´z ghetto, children, one dressed as a ghetto policeman, play a peculiar version of cops and robbers, 1943, USHMMPA WS# 80401, courtesy of Beit Lohamei Haghetaot.

Innocence and Knowledge

Innocence is a characteristic closely associated with childhood. And yet, as the testimony of Aharon Peretz and the anecdotes of Hanna Hoffmann-Fischel show, most Jewish children did not long remain in ignorance of the perilous circumstances in which they found themselves during the Holocaust. As a rule, innocence suggests a kind of purity that stems from the ignorance of evil and an absence of worldliness and guile. Yet, living in the upside-down world of the ghetto or in the charnel atmosphere of the concentration camps, many children had become well acquainted with evil and understood from their own limited experience that guilelessness and naiveté could prove a deadly combination. Here youngsters grew up quickly. At a tender age, many had witnessed unimaginable horrors and shouldered adult responsibilities. Łódź ghetto chronicler Josef Zelkowicz noted this premature maturation during that ghetto’s notorious Gehsperre. In the late summer of 1942, German authorities approached ghetto elder Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski demanding twenty thousand deportees. Faced with an ultimatum, Rumkowski settled upon a desperate and terrible solution; he would fill the prescribed quota with the least productive members of the community: the severely ill, the aged, and all children up to the age of ten. From September 5 through 12, 1942, German forces entered the ghetto, seizing those unfit for labor from their homes and from the community’s streets. The Gehsperre began with the liquidation of the ghetto hospitals, where SS officials apprehended patients in their beds. In the days that followed, police units cleared schoolrooms and orphanages, many of them in Marysin, once a haven for Łódź’s youngsters. Approximately 15,500 individuals were rounded up for deportation; the vast majority of these victims were young children and adults over the age of sixty-five.32

32. See Isaiah Trunk, Łódź Ghetto: A History, ed. and trans., Robert Moses Shapiro (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press in association with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2006).

Josef Zelkowicz recorded the events of the Gehsperre in a 1942 anthology of essays he called In Those Terrible Days.33 Amid the chaos of the September roundups, Zelkowicz noted that most youngsters were well aware of the terrifying implications of the razzias, although parents often chose not to share the news of the upcoming tragedy with their youngsters.

33. See the essay in its entirety in Josef Zelkowitz, In Those Terrible Days: Writings from the Lodz Ghetto, ed. Michal Unger, trans. Naftali Greenwood (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2002), 249–381.

Some children [. . .] have caught on. And that is because ten-year-olds in the ghetto are already adults. They know and understand the fate that awaits them. They may not, for now, know why they are being torn from their parents; this may not have been explained to them. For now it suffices to know that they are being separated from their trusted guardians, their devoted mothers and fathers. [. . .] They already rove alone in the street. They already cry their own tears, and these tears are so bitter and stinging that they pierce the heart like poisoned arrows. . . . The ghetto hearts, however, have ossified. They wish to break but cannot. This may be the cruelest curse of all.34

34. Zelkowitz, In Those Terrible Days, 265–67.

Of course very young children could not fathom—as their parents might—the terrible significance of the roundups or the fate that awaited them at the Chełmno killing center. As Zelkowicz observed that autumn, some youngsters stood in carts bound for the collection point, bemused by the cacophony and the laments of adult bystanders, eager for the “game” to continue.

Document 8-12. Excerpt from Josef Zelkowicz’s essay “The Optimist in the Potato Queue,” Łód´z ghetto, September 5, 1942, in Josef Zelkowicz, In Those Terrible Days: Writings from the Lodz Ghetto, ed. Michal Unger, trans. Naftali Greenwood (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2002), 306–7.

A cart stands on Rybna Street. Several children are standing in the cart, their eyes wide, as if they were lost. They have already been “nabbed”—gekhapped. They do not know what all these people want from them. Why are all these people standing around them and gazing at them sadly? Why are they crying? Why are they pounding their chests in despair?

These children see no reason to cry. They are quite content: they have been placed on a wagon and they are going for a ride! Since when have children in the ghetto had such an opportunity? If it were not for all those wailing people, if their mothers and fathers had not screamed so as they placed them in the cart, they would have danced to the cart. After all, they are going for a wagon ride. But all that shouting, noise, and crying upset them and disrupted their joy. They jostle in the elongated wagon bed with its high barriers, as if lost, and their bulging eyes ask: What’s going on? What do these people want from us? Why won’t they let us take a little ride?

Document 8-13. Young children from the Marysin colony wait to be conveyed to the deportation assembly point during the Gehsperre, Łód´z ghetto, September 1942, USHMMPA WS# 50334, courtesy of the Instytut Pamieci Narodowej.

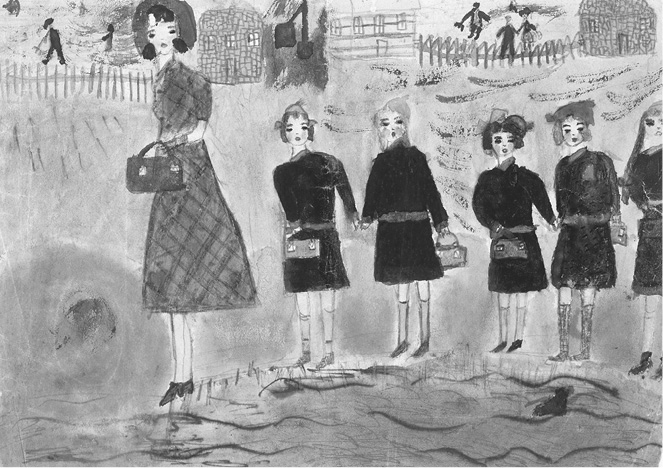

“Draw what you see!” Inspired by her father’s injunction, Helga Weissová began to sketch her observations of ghetto life shortly after her arrival in Theresienstadt in December 1941.35 Helga was born on November 10, 1929, to Otto Weiss, a state bank official, and his wife, Irena. The family led a comfortable middle-class existence in the Czech capital, and from an early age young Helga occupied much of her free time with drawing and painting. Exactly one month after her twelfth birthday, Helga arrived with her parents on one of the first transports of Czech Jews to Theresienstadt. The youngster would remain at Terezin for almost three years, during which time she completed over one hundred drawings and illustrations. In late 1944, Helga and Irena Weissová were deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp. Due to the continuing advance of the Soviet army, the two women were transported almost immediately to a series of camps in the German interior. In the last days of the war, the pair found themselves in the Mauthausen concentration camp, where American forces liberated them and their fellow prisoners on May 5, 1945. Mother and daughter returned to Prague, where they learned of the deaths of Otto Weiss and most of their nearest relatives and acquaintances. Helga Weissová pursued a career in graphic arts at the National Academy of the Arts and in 1954 married Czech musician Jiři Hošek. She became an internationally celebrated artist, settling in her native Prague.

35. For a more extensive view of Helga Weissová’s life and Holocaust-era drawings, see Helga Weissová, Zeichne, was Du siehst! Zeichnungen eines Kindes aus Theresienstadt/Terezin, ed., Niedersächsischen Verein zur Förderung von Theresienstadt/Terezin, e.V. (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 1998).

Helga began to ply her artistic talents in Terezin shortly after settling into Mädchenheim L-410, one of the ghetto’s homes for young girls, in December 1941. Using art supplies that she had packed with her at the time of her deportation, Weissová initially sought to ease her loneliness by drawing upon the happy images of her girlhood in Prague. After painting a nostalgic winter scene in which small children built a snowman, she persuaded fellow prisoners to smuggle the picture to her father in the men’s barracks. Otto Weiss, who had constantly championed his daughter’s artistic endeavors, admonished Helga instead to draw what she observed around her. “That snowman was actually my last genuine drawing as a child,” Weissová later recalled. “Through this sentence of my father’s, and through my own inner motivation, I felt called from now on to capture in my drawings the everyday life of the ghetto. The impressions that from this point in time would affect me, ended my childhood.”36

36. Weissová, Zeichne, was Du siehst! 13.

Twelve-year-old Helga clearly comprehended the dangers of her new environment in Theresienstadt and resolved to record them on paper and canvas. For the next several years, she created paintings and illustrations that captured the quotidian incidents and tragedies of ghetto life. “We all did the same things, with the exception of Helga—who, when she was not working, used to sit on her bed and draw and paint constantly,” Charlotta Verešová,37 a child diarist of Theresienstadt, remembered of her friend and bunkmate. “We all admired her because she was able to depict our plight.”38 With an unsettling candidness, the young teenager faithfully portrayed the wrenching arrivals and departures of transports at Terezin, the unending lines to receive meager rations, the colonies of workers going to forced labor. Helga had an eye for the ironic, depicting with unvarnished candor the macabre and surreal aspects of ghetto culture. We feel for the aged German Jews who arrive at the “rest community for the elderly,” promised them by the Nazi government, only to encounter the ugly and deadly reality of Theresienstadt. We are likewise amused by the farcical efforts of camp authorities to create from Terezin a “model ghetto” for the visit of officials from the International Committee of the Red Cross in 1944. Other illustrations capture the pathos and suffering of Helga’s fellow prisoners: the faces of deportees waiting for days in the cold or heat of the ghetto’s dreaded “Sluice”39 before their transport to Auschwitz or ghetto residents’ solemn farewells to their dead comrades, who were daily carried on sledges to a crematorium outside the ghetto.

37. Charlotta Verešová was born on December 13, 1928, in Litoměřice, Czechoslovakia, the daughter of a mixed marriage. At age fourteen she was separated from her family and deported to Theresienstadt, where she kept a diary of her time in confinement. Verešová survived the war in the Terezin ghetto and worked as a librarian and technical designer after the war; see Laurel Holliday, Children in the Holocaust and World War II: Their Secret Diaries (New York: Washington Square Press, 1995), 201–7.

Sometimes Helga deployed her artistic gifts in a more traditional vein: to create a birthday greeting or a holiday card for friends and loved ones. In Birthday Wish I (Pŕání k narozeninám I), she transcends the hunger and deprivation of the ghetto by conjuring a delicious torte for the birthday honoree. Here a childish yearning is fulfilled as a young boy and girl, clad in their summer best, wheel an enormous birthday cake from Prague to Theresienstadt. The fourteen-year-old artist gave her native city gauzy contours; one can make out the prominent features of Prague Castle—the Hradschin—in its outlines. The well-dressed youngsters push the gigantic confection through the green landscape and up to the fortress walls of Terezin. On the surface, the composition is a dreamlike, innocent vision, like a fairytale from childhood. But the idyllic scene bristles with dark humor. The cart that carries the mighty cake is a hearse, a conveyance often used in Theresienstadt to transport items. In another stroke of wit, the wagon seems to bear the inscription “Entsorgung” (waste disposal). Perhaps the young artist meant to suggest that her diminutive helpers have cleared the ghetto of its debris and brought back in its place a wonderful cake?

Document 8-14. Watercolor by Helga Weissová, Birthday Wish I (P´rání k narozeninám I), Theresienstadt ghetto, December 1941, USHMMPA WS# 60926, courtesy Helga Weissová.

A third document concerning innocence and knowledge strikes out into different territory. The opening pages of this book introduce the reader to Elisabeth Block, a Jewish teenager living in rural Bavaria. As Peter Miesbeck, the historian who helped to publish Block’s journal in 1993, noted, Elisabeth was “no Bavarian Anne Frank,”40 who described her experiences explicitly and in vivid detail. Indeed, her diary is interesting to scholars because, even in the blackest moments of her personal history, she appears almost pathologically unable to record unpleasant developments. It is certainly true that in the village of Niedernburg, near Rosenheim, Elisabeth and her family felt closely integrated into the small community in which they lived and endured little discrimination at the hands of their neighbors, even as Nazi anti-Jewish policy escalated in the late 1930s. Elisabeth was loath to record those encroachments that the government’s antisemitic measures made on her family’s economic and social circumstances during these years. During Kristallnacht, for example, rampaging Sturmabteilung (SA) men had murdered Elisabeth’s uncle, Dr. Leo Levy in his apartment in Bad Polzin, an event the teenager referenced only in passing in her journal. Further disturbing developments—the exclusion of Jewish pupils from public schools, the loss of the family home and business, and the compulsory sterilization of Elisabeth’s father, Fritz Block—received similarly short shrift. It was as if the young girl failed to see herself and her family within the wider framework of Nazi persecution. In her diary, coincidentally begun in 1933, Block uses the phrase “we Jews” just once, in the context of the September 1941 decree requiring German Jews to wear the yellow star.41

40. Elisabeth Block, Erinnerungszeichen: Die Tagebücher der Elisabeth Block, ed. Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte/Historischer Verein Rosenheim (Rosenheim: Wendelstein-Druck, 1993), 17.

41. Block, Erinnerungszeichen, 25.

On March 8, 1942, Elisabeth Block wrote the last entry in her journal. As usual, she focused on her daily activities, on her interactions with friends and family members, on the weather, and on events that had transpired in her community. In this instance, the latest excitement was the birth and baptism of little Friedi, the newborn daughter of Elisabeth’s friend Regina Zielke, in Benning, a little town two kilometers from Niedernburg. Elisabeth had been deployed to a farm in the vicinity in compliance with a March 1941 decree compelling all able-bodied Jews to undertake compulsory labor assignments. It is clear from the teenager’s own descriptions of her experiences and from contemporary eyewitnesses that she was well treated on the farmstead and that she and her employers felt she was part of the family there. This may explain in part why she makes so little mention of the summons by the local labor office (Arbeitsamt) dispatching her to agricultural work or of the fact that her service there, however agreeable, was essentially forced labor.42 Elisabeth pays little attention to her father’s more strenuous compulsory service laying tracks for railway and commuter transit lines. In her March 1942 account, she mentions only that the frostbite that Fritz Block contracted from his heavy work in freezing weather had fortunately occasioned him leave at a time when the family could spend the weekend together.

42. German Jews performing compulsory labor in accordance with the 1941 decree were not entitled to compensation, paid leave, or benefits, which German “Aryan” workers received.

Most notably missing from Elisabeth’s March 1943 entry is mention of the Blocks’ fear of imminent deportation “to the East.” The exact date on which they received their summons to assemble at the collection point (Sammelstelle) in Munich-Milbertshofen is unknown, but in the early weeks of March, when the teenager wrote of Friedi’s baptism and her winter sleigh ride, the family had clearly already begun packing up their household, gathering those few possessions they might be allowed to carry with them and storing furniture and valuables with trusted friends and neighbors.43 Eighteen years old when she wrote the last passage in her diary, Elisabeth could scarcely have been ignorant of the mass deportation of Jews from Germany and the policy’s significance for herself and her family. Was her silence on this point a matter of discretion or circumspection? Did her refusal to acknowledge these menacing developments spring from denial or a naive belief that the charmed existence she and her loved ones enjoyed in Niedernburg would continue, even as the rest of her coreligionists were sent to their deaths? We will never know. On April 3, 1942, the Blocks were deported with 989 fellow Bavarian Jews to the Piaski ghetto, near Lublin, in German-occupied Poland. On an unknown date, Elisabeth and her family were transferred to a killing center, presumably Bełżec or Sobibór, and murdered there.

43. See Block, Erinnerungszeichen, 46.

Document 8-15. Diary of Elisabeth Block, entry for March 8, 1943, in Elisabeth Block, Erinnerungszeichen: Die Tagebücher der Elisabeth Block, ed. Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte/Historischer Verein Rosenheim (Rosenheim: Wendelstein-Druck, 1993), 265–66.

Sunday, March 8, 1942

It has already been seven weeks now that I have not written in my diary, a long time, and what has happened in the meantime! The most important and greatest event would be the birth of the little Friedi on Wednesday, January 28.44 That was a terribly exciting day. The hard struggle lasted from ten a.m. until four in the afternoon, then finally there was a black-haired, healthy girl there. On Friday, amidst a terrible snowstorm and deep snow, the little tot [Butzerl] was carried, heavily bundled, to the baptism. Christl stood up as the godmother. To everyone’s great surprise and joy, Mama came in the afternoon, just in time to attend the christening luncheon and to inquire after the mother and child. The farmer’s wife was very touched that Mama dared to come in such weather and walked two hours, but I was very happy to be able to speak my piece on the subject again.

44. Emphasis is in the original.

The whole time until February 22, it snowed practically every day, so that we had three-quarters of a meter [2.5 feet] of snow, and with it minus 16 to 20 degrees (Celsius) [3.2 to –4 degrees Fahrenheit] and even a week of 35 degrees below zero [–31 degrees Fahrenheit]. My daily work now consists of laundering, mending, and darning. In the mornings the farmer’s wife (and I) get up at quarter to seven and milk our nine cows—recently I even milked seven of them by myself—and are finished cleaning the stalls by 8:30. We have just had three calves and now have twenty-four head of cattle. After breakfast at 10:00, when the living room, foyer, and kitchen have been cleaned, I do the wash; after the midday meal at 12:30, I go back to the stalls to clean the stable and water the animals. After this there is the mending, and at 6:00 p.m. back out to the stall. That is the daily flow of things, to which is added the washing of the cows and calves and scouring of the house on Saturday.

From January 18 till February 2, I was not at home; but it was so convenient that I could go ride along for a few hours by sleigh by riding with Christl and Gina-Maus because [their trip] coincided with a farmer’s holiday.45 That was really fun, and it appeared to me as if [the scene] came out of a novel or a winter’s tale, riding in a charming horse-drawn sleigh through the winter landscape, bundled warmly. And when home, what a surprise, Papa was home; he had frostbite on his fingers and had leave—the timing was perfect. We all drank coffee together, and then they were off once more, but I was happy when I came again into the warm living room, because I was completely frozen when I arrived.

45. February 2 is Candlemas in the Christian calendar.

In Hopes and Dreams: Coping with the Holocaust

Perhaps Elisabeth Block’s aversion to recording unpleasant developments represented a strategy to cope with the increasingly difficult circumstances in which she found herself. It is possible that the teenager used her diary to rewrite events: to reshape painful experiences, giving them gentler and less threatening contours. In recasting each day without its uncertainties and adversities, she may have discovered a way to regain a sense of control over her situation and to replace disagreeable memories with those thoughts of home, nature, and family that she treasured most.

Children adopted many strategies to help them adapt to the horrors and deprivations of the Holocaust. Youngsters matured quickly and beyond their years under such conditions, and many of their responses to persecution were practical and pragmatic. Often powerless to shape their individual circumstances in the way that adults could, however, children frequently found highly creative ways to cope with the terrors they faced. Through imagination, play, and their dreams for the future, young people were able to transcend the physical and emotional traumas they experienced and cling to their hopes for survival.

Where possible, adults contributed to this process. Through educational activities and structured play, teachers and caregivers worked to create a world in which children could thrive and feel secure, if only temporarily. In the Theresienstadt family camp in Auschwitz, dedicated instructors like Hanna Hoffmann (later Hanna Hoffmann-Fischel) constructed a safe haven for youngsters in the so-called Kinderblock (children’s block) located in the midst of the killing center in Birkenau. Under the aegis of Fredy Hirsch, a popular youth leader in the Theresienstadt ghetto, teachers in the children’s home organized craft workshops and cultural events for their young charges. A high point for the youngsters was the staging of a play adapted from the beloved Walt Disney film Snow White, produced in 1937.

Document 8-16. Personal testimony of Hanna Hoffmann-Fischel, c. 1960, in Inge Deutschkron, Denn ihrer war die Hölle: Kinder in Gettos und Lagern (Cologne: Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, 1965), 52–55 (translated from the German).

We taught lessons in sociology, Jewish history, etc. When the SS men came for inspection, the children had to recite poems in the German language while standing at attention. It was thanks to Fredy’s exemplary leadership that the SS were pleased with the Kinderblock and often showed it off as a curiosity to the commandants of other camps. They also provided us with further favors. Thus, for example, we could even establish a sewing room in the block.

For the home, one of our comrades painted pictures from Walt Disney’s Snow White. At the German’s request, as they were very impressed by the pictures, Fredy produced a play of the fairy tale with the children in the German language and performed it for the dignitaries at Auschwitz. From tables, stools, and straw sacks, we constructed the stage, the backdrop, and the costumes. Because of the language difficulties which had to be overcome, the rehearsals lasted three months. We practiced dances and choruses with the children, rewrote the script, and adapted it to our circumstances. Thus the dwarves appeared as representatives of order and cleanliness. The demoralization to which they were opposed was embodied by the wicked stepmother. It was a truly lovely performance, and for the children it was the grandest experience of their lives—for many of them unfortunately also their last.

It was thanks not least to this performance that the SS-Lagerführer put aside a second block, as a day care center for children from three to eight years old and into whose living quarters mothers with children up to the age of ten could move. In this way, we could also look after the children at night, and prevent the exchange of children’s food for other goods and services. [. . .]

After a while, we succeeded in translating the harmony which existed among us youth leaders unto the children themselves. We initiated a boy scout system, with challenges that had to be undergone; the children composed slogans and songs. The groups competed with each other to see if each one in the group could do a good deed each day for fourteen days straight. We organized scouting games, made playthings from clay, colored woven straw, and paper, which we later displayed in an exhibition where they were very much admired by the Germans.

This world, into which we had fled from reality, was suddenly shaken to its foundations in early March 1944. We had already spent the three winter months in Birkenau; those from the September transport had even been there for six months. And nothing had happened up until then. Of course many had perished, dead of starvation, and there were more and more Muselmänner. But the roll calls were shorter and occurred less frequently. Block curfew [Blocksperre] was seldom declared. Those of us who did not suffer from “chimney fever”46 had new cause for hope. But one day the camp elder announced that those from the September transport would be going as a unit to work in Heidebrück in Germany—men, women and children; only the very ill would be exempted. There began a wild guessing game as to where this Heidebrück would be and if it was also a concentration camp. The pessimists maintained that this time certainly they would go to the gas: saying that the chimneys had not been smoking for many days now and they needed new material for burning. The optimists saw this very fact as proof that the gas chambers would be shut down for good.

46. That is, fear of being gassed.

The pessimists maintained correctly: the September transport, to which nearly all of these children belonged, was within a short time sent to the gas chamber.

Document 8-17. Just as youngsters at Birkenau reenacted Snow White, children in the Novaky labor camp perform a play about another popular Disney character, Mickey Mouse, Slovakia, 1944, USHMMPA WS# 40080, courtesy of Mira Frenkel.

Separation from loved ones was a central experience for many young persecutees during the Holocaust. Whether divided by long distances or isolated in hiding, youngsters often bore the pain of separation in silence, either because they lacked a sympathetic environment in which to express their emotions or because doing so might endanger themselves or their rescuers. Very young children, such as hidden child Ilona Goldman (later Alona Frankel), suffered doubly, for they had very few practical avenues to communicate with parents or family members or to convey their feelings of loneliness and abandonment. Born in Kraków on July 27, 1937,47 Ilona was two years old when German forces invaded her native Poland in September 1939. Like many Jewish families, the Goldmans decided to escape German-occupied Poland and fled to Lvov (now Lviv), then in Soviet territory.

47. Concerning the story of Ilona Goldman and her family, see Alona Frankel, A Girl, trans. Sondra Silverston (Ramat Gan: Institute for the Translation of Hebrew Literature, 2009).

Her father, Salomon (1900–1958), a Communist Party member from nearby Bochnia, owned a wholesale materials business. Her mother, Gusta (b. 1904), a Ha-Shomer Ha-Za’ir48 youth group member who had spent her teenage years in Palestine, came from the Silesian town of Oświęcim, a city better known by its German name, Auschwitz. Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Goldman family found itself incarcerated in the Lvov ghetto. In the spring of 1942, fearing the upcoming liquidation of the ghetto, Salomon Goldman managed to escape with his family to the “Aryan side” of Lvov, where a former employee, Josef Jozak, agreed to hide the Goldmans on one condition: that they find another place of concealment for their lively and voluble four-year-old daughter.49 In the end, Salomon and Gusta found a hiding place for young Ilona with a Polish peasant family in the small village of Marcinkowice. Ilona spent some six months there posing as a Christian child with the family of Hania Seremet, whom the Goldmans paid handsomely each week for the care and concealment of their daughter. In Ilona’s last months with her foster family, Gusta Goldman sacrificed a gold dental crown every week for her only child’s continued safety, with Salomon prying each tooth from her mouth with the help of his Swiss Army knife.50 The Goldmans were careful to pay Seremet on schedule, for they had learned that the rescuer had abandoned an earlier charge, a very young boy, to his death when his parents were killed in a ghetto action and relatives were unable to pay for his continued upkeep.51

48. Ha-Shomer Ha-Za’ir (also Hashomer Hatzair, youth organization of socialist Zionism) was founded in 1918, merging two groups, Hashomer, a Zionist scouting group, and Ze’irei Zion, an ideological group committed to the study of Zionism, socialism, and Jewish history. The oldest existing Zionist youth movement, Ha-Shomer Ha-Za’ir encouraged Aliyah to Palestine and the establishment of kibbutzim; it counted among its members Mordecai Anielewicz, leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

Ilona Goldman spent several months separated from her parents. Because the four-year-old had not yet learned to write, she could not converse with her parents through notes or letters. Instead she communicated with them through a series of drawings sketched on the reverse side of Seremet’s weekly correspondence with the Goldmans. Besides the connection they established between parents and child, Ilona’s drawings served another important purpose: the pictures assured the Goldmans on a weekly basis that their daughter was still alive.

Now in the collection of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Ilona Goldman’s childhood drawings capture the themes of village life: the work of peasants in the fields, animals ambling across green meadows, passenger trains traversing the Polish countryside. Wartime shortages also found a place in Ilona’s sketches. During her time in hiding in Marcinkowice, the little girl had heard incessant complaints from local farmers about the continual shortages of consumer items, especially cigarettes and smoking materials. Tobacco, hard to come by in wartime, was strictly rationed. In the drawing in Document 8-18, Ilona has rectified the situation. As the residents of her rescuer’s household engage in hunting for mushrooms, a common family pastime in late summer and early autumn, the menfolk drag at their cigarettes. The farmers smoke; the house chimney smokes; yes, even the bird aloft in the sky seems to take a few puffs.

Sometime during that autumn of 1942, Ilona’s caretakers lost courage and returned her to her parents in their hiding place. For months, the child lived in a kind of double concealment: hidden from the reach of German officials and from the Jozaks, who had forbidden the Goldmans to keep Ilona with them. In July 1944, the Soviet army liberated Lvov and, with the city, the emaciated family. In 1949 the Goldmans emigrated to Israel, where Ilona established herself as an award-winning children’s author and illustrator.

Document 8-18. Drawing of Ilona Goldman (Alona Frankel) for her parents in hiding, Marcinkowice, Poland, 1942, USHMM Collections, gift of Alona Goldman Frankel (note: writing showing through from other side).

Ilona Goldman’s drawings served both as a mode of communication with absent parents and as a means of entertaining herself during her long and lonely time in hiding. For many children during the Holocaust, escape into a world of imagination proved an efficacious way to eschew the harsh realities that surrounded them. Whether through drawing, painting, poetry, or play, imagination provided an important avenue for eluding the miseries of hunger, fear, and deprivation. For young Abram (Avraham) Koplowicz, writing became a way to reassert a sense of control over his environment and to banish feelings of pain and helplessness. Born in Łódź on February 18, 1930, the only child of Mendel and Yochet Koplowicz (née Gittel),52 Abram was just nine years old when German troops entered his native city and forced its Jewish inhabitants to reside in the Łódź ghetto. Even in his preteen years, he showed a precocious talent for writing, and within the ghetto walls, the young boy turned to poetry to transcend the physical and spiritual barrenness of his surroundings. His poem “When I Am Twenty” is a literal flight into fancy, a magical journey into a space and time where the horrors of the ghetto could not reach him.

52. Institute of Tolerance/State Archives in Łódź (in cooperation with the Centre de Civilization Française and the Embassy of France in Poland), eds., The Children of the Łódź Ghetto (Łódź: Bilbo, 2004), n.p.

Abram Koplowicz was deported with the transport from the Łódź ghetto to Auschwitz in August 1944 and perished in the Birkenau gas chambers in September of that year. Mendel Koplowicz succeeded in surviving the war and, on returning to Łódź, discovered his son’s illustrated volume of poetry among the ruins of the ghetto. Abram Koplowicz’s original copybook is now reposited in the archives of Yad Vashem. Several selections of the young boy’s poetry were published in their original Polish in 1993.53

53. Abramka Koplowicz, Utwory własne: Niezwykłe świadectwo trzynastoletniego poety z łódzkiego getta (Łódź: Oficyna Bibliofilów, 1993).

Document 8-19. Abram Koplowicz, “When I Am Twenty,” Łód´z ghetto, c. 1943, in Institute of Tolerance/State Archives in Łód´z (in cooperation with the Centre de Civilization Française and the Embassy of France in Poland), eds., The Children of the Łód´z Ghetto (Łód´z: Bilbo, 2004).

When I Am Twenty

When I am twenty,

I will start admiring our beautiful world

I will sit down in a huge motor-bird

And I will rise heavenward

I will sail, I will fly over rivers, seas and skies

Clouds will be my sisters, winds will be my brothers

I’ll be watching rivers: Nile, Euphrates and others

I’ll see the sphinxes and the pyramids

In the old country of divine [Isis].

I’ll conquer the huge water of Niagara

And I’ll be sunbathing in the heat of the Sahara

Over Tibetan mountains which reach for the sky

Over wonderful and mysterious land of the magicians

And when I finally leave the kingdom of heat

I’ll rush flying to see the ice of the North

I’ll fly over the great kangaroo island

And over the ruins of the Pompeian walls

Over the Holy Land of Orthodox Order

And over famous Homer’s mother country

I’ll be stunned by our beautiful world

Clouds will be my sister, wind will be my brother.

Lvov ghetto survivor Nelly Toll used her interest in painting to transcend the dangerous world in which she lived. She was born Nelly Landau in 1933, the only daughter of Sygmunt and Rose Landau.54 With her parents and her younger brother, Janek (b. 1937), Nelly resided in Lvov,55 where her father was an affluent businessman who owned several apartment buildings. When Lvov came under Soviet occupation in the early months of World War II, Sygmunt Landau went into hiding, fearing arrest by the Soviets as a “wealthy capitalist.” The family was therefore initially relieved when German troops arrived in the region on June 30, 1941, and Sygmunt could leave his hiding place and rejoin his loved ones. The Landaus’ enthusiasm for the new Nazi occupiers was short-lived, however, as German authorities quickly initiated draconian legislation against the large local Jewish population.

54. For information concerning Nelly Landau Toll and her Holocaust experiences, see Nelly S. Toll, Behind the Secret Window: A Memoir of Hidden Childhood during World War Two (New York: Dial Books, 1993).

55. Before World War II, Lvov had the third-largest Jewish population in Poland, numbering nearly one hundred thousand individuals; this number nearly doubled during the period of Soviet occupation with a rapid influx of Jewish refugees from German-occupied Poland.

On November 8, 1941, the Germans established a ghetto in the city’s northern districts and, by December 15, had forced all Jews in the municipal area into the sealed “Jewish quarter.” The Landaus’ initial strategy was to place Nelly with a Catholic family outside the ghetto until the war’s end. In hiding, the eight-year-old began to use the world of fantasy to cope with the intense loneliness and confusion she experienced. While the young girl lived clandestinely on Lvov’s “Aryan side,” she imagined that she was journeying on a long trip without her parents. During her later time in hiding, she would capture the sense of isolation she felt during these weeks in a wartime self-portrait that she titled All Alone.

Nelly tried to make the best of her time with her kindly Polish guardians, but a few short months later, tragedy struck. Nelly’s younger brother, Janek, together with his aunt and young cousin, was caught up in a wave of deportations from Lvov and murdered, presumably in the Bełżec killing center. After Janek’s death, Nelly returned to her parents in the ghetto. Sygmunt Landau was now more desperate than ever to rescue his remaining family from the Nazi dragnet. After an ill-fated attempt to escape to Hungary, Landau succeeded in finding a hiding place for his wife and daughter. Drawing on earlier loyalties and proffering a handsome sum as compensation, he convinced his former Polish tenants Michaj and Krysia Wojtek to conceal Nelly and her mother in a hidden room in their apartment. Sygmunt planned to join them there as soon as he had found places for members of his extended family. Yet, a short time after his wife and daughter went into hiding, Sygmunt Landau disappeared without a trace; Nelly and Rose Landau never saw him again.56

56. After Soviet authorities liberated Lvov, Rose Landau tried, without success, to learn the fates of her husband and other family members still incarcerated in the Lvov ghetto at the time of their concealment. Sygmunt Landau likely perished at Bełżec.