Chapter 9

Children and Resistance and Rescue

This chapter addresses a theme traditionally important to Holocaust discourse: resistance. In this case, the subject is children’s resistance, a theme often overlooked in monographs dedicated to active opposition to Nazi rule. Boys and girls in their teens participated in armed resistance, their tender ages belying their achievements as partisans, ghetto fighters, and members of organized resistance groups. Youngsters struck at Nazi genocidal policy in uprisings at concentration camps and killing centers, such as the prisoner revolt at Sobibór in 1943 (Document 9-2). Children lived in family units protected by partisan bands in the forests of eastern Europe (Document 9-4). Young people formed the core of insurgents who battled Nazi forces in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (Document 9-1) and in other armed struggles in ghettoized communities under Nazi occupation. More often, however, children engaged in acts of unarmed resistance, as with the publication of clandestine youth newspapers in the Warsaw ghetto (Document 9-5) or through the provision of aid and intelligence to armed opposition movements (Documents 9-8 and 9-9). Even young children practiced solitary acts of defiance against Nazi authorities, often as smugglers risking their lives to bring food and essential goods to fellow ghetto inhabitants from outside the ghetto boundaries.

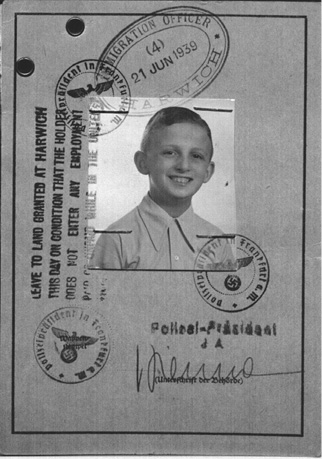

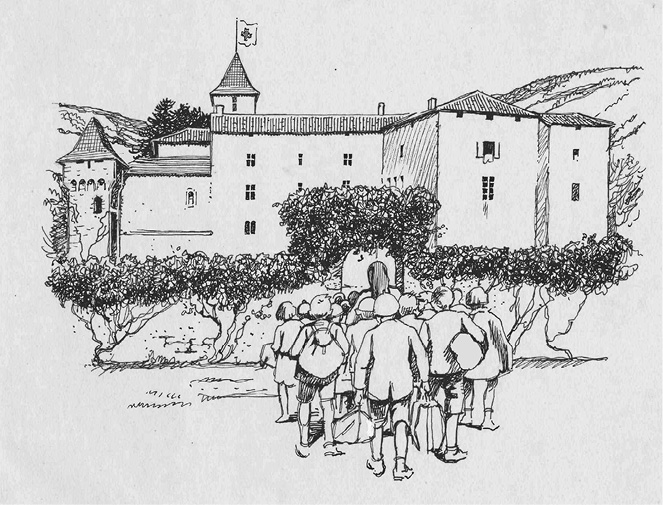

Rescue is the mirror image of resistance. Hundreds of organizations and thousands of committed individuals worked to save persecutees in Axis-occupied Europe. Many of these focused principally or solely on the rescue of children. In Allied countries, refugee organizations sought to bring children to the safety of their shores. In England, associations such as the British Committee for the Jews of Germany and the Movement for the Care of Children from Germany organized the famous Kindertransporte, which carried Jewish and refugee children to Great Britain (Document 9-13), an effort that many private benefactors worked to emulate (Documents 9-14 and 9-15). Within Nazi-occupied territories, children’s aid organizations such as the Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants in France and the Żegota, an auxiliary branch of the Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa), proved particularly successful in removing young children from concentration and internment camps and concealing them from Nazi authorities in a series of safe houses and children’s homes. Finally, thousands of young Jewish children spent the war in hiding, either alone or with their families, shielded by a network of rescuers and protectors. These so-called hidden children (Documents 9-10 through 9-12) have become an iconic symbol of rescue efforts during the Holocaust, but the following documentation demonstrates that a dense nexus of individuals, aid organizations, and child-welfare agencies worked tirelessly and with singular ingenuity to save Jewish and non-Jewish children from harm in Nazi Europe.

Youth and Armed Resistance

One of the most ambitious and fiercely contended insurgencies against Nazi genocidal policy, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising had its origins in the perceived defenselessness of Warsaw’s incarcerated Jewish population during the time of the Great Deportation Action, a period between July 22 and September 21, 1942, when German authorities dispatched three hundred thousand ghetto inhabitants to the Treblinka killing center. On July 23, the day the first massive deportation effort from Warsaw began, members of the ghetto’s underground movement met to discuss a plan of action that might save the endangered community. Representatives of Warsaw’s Jewish youth organizations, which had thus far played a vital role in ghetto resistance, favored the formation of a defense force that might resist further deportation measures through armed intervention. On July 28, 1942, members of the Ha-Shomer, Dror, Ha-Za’ir, and Akiva movements founded the Jewish Fighting Organization (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa, or ŻOB) under the command of twenty-three-year-old Ha-Shomer Ha-Za’ir1 organizer Mordechai Anielewicz.2 In the coming months, activists from the ŻOB distributed leaflets to the ghetto populace informing them of the significance of the Treblinka camp and the fate of persons deported there. More significantly, its leaders made overtures to the Polish Home Army and the Polish communist underground in an attempt to acquire arms, with limited success. In the autumn, another resistance organization, the Jewish Military Union (Żydowski Związek Wojskowy, or ŻZW) formed under the auspices of the Revisionist Zionist associations. For a time the two defense forces vied for men and material, but in the face of renewed deportations from the ghetto, the ŻZW accepted the ŻOB’s authority, and the two bodies worked to coordinate their activities.

1. See note 48, chapter 8.

2. Mordechai Anielewicz (1919–1943) was born in the small town of Wyszków, near Warsaw, Poland. In his late teenage years, he joined, and became a local leader of, the Zionist youth movement Ha-Shomer Ha-Za’ir. In early 1943, Anielewicz was instrumental in organizing the first clashes with German forces during the brief January deportation action in the Warsaw ghetto. As the leader of the ŻOB, he played a chief role in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of April 1943. It is believed that Anielewicz committed suicide with other leading resistance figures when German forces captured ŻOB headquarters on May 8, 1943. See Norah Levin, Mordechai Anielewicz: Leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (Philadelphia: Association of Jewish Holocaust Survivors in Philadelphia, 1988).

On January 18, 1943, a second wave of deportations to Treblinka began. This time, members of the ŻOB engaged German forces in combat. Encouraged by the resistance fighters, thousands of ghetto inhabitants refused to show in response to German deportation summons in the days that followed. Nazi officials succeeded in rounding up five to six thousand Jews and halted the action after a few days. Jews and “Aryan” Poles alike interpreted the brevity of the deportation action as a victory for the ghetto’s defense organizations. The heroism of the ghetto fighters, together with the realization that any further deportation efforts would mean the final liquidation of the ghetto unit, worked to undercut the authority of the Jewish Order Police and the Judenrat, which had counseled against armed resistance. The ŻOB had given ghetto inhabitants a measure of hope, and the population gave its allegiance to the ghetto resistance leaders in the days to come. In the winter months of 1943, the preparation of bunkers and subterranean hiding places (malines) proceeded on a massive scale, while ghetto defense forces worked to consolidate their strategies and to arm and equip themselves for the coming battle. The commanders of these units were under no illusion that their resistance efforts would lead to rescue: most viewed the upcoming revolt as a last protest against Nazi Germany’s murderous policies and an attempt to live and die with their honor intact.

The resistance campaign known as the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising began on the evening of Passover on April 19, 1943.3 The ŻOB had received advanced warning of this final deportation action and prepared assiduously for the coming attack. From their experiences in January, German authorities likewise had knowledge of the ghetto’s defense organizations and, on the eve of the action, replaced the chief of the Schutzstaffel (SS) and police in Warsaw, Obergruppenführer Ferdinand von Sammern-Frankenegg,4 with SS and Police Leader (SS- und Polizeiführer) Jürgen Stroop,5 a man with considerable experience in partisan warfare. The uprising lasted twenty-seven days. Stroop had committed a considerable force, some 2,054 soldiers and police, reinforced with artillery and tanks. Clashing with them, sometimes in hand-to-hand combat, were some seven hundred young Jewish fighters, poorly equipped and lacking in military training and experience. The ŻOB did have the advantage of waging a guerrilla war, striking and then retreating to the safety of ghetto buildings and rooftops. The general population likewise thwarted German deportation efforts, refusing to assemble at collection points and burrowing in malines and underground bunkers. In the end, German troops were obliged to burn the ghetto down block by block in order to smoke out their quarry. The ghetto fighters and the population that supported them held out for nearly a month. On May 8, 1943, German forces succeeded in seizing ŻOB headquarters at 18 Mila Street; Anielewicz and many of his staff commanders are thought to have committed suicide in order to avoid capture. On May 16, Stroop announced in his daily report to Berlin that “the former Jewish Quarter in Warsaw is no more.”6 Some thirteen thousand Jews had died in the uprising, while the remaining fifty thousand Warsaw ghetto residents were deported to Treblinka. Only a handful of ghetto inhabitants survived the final Aktion in Warsaw, subsisting in their subterranean hiding places or escaping through the city’s labyrinthine sewer system to the “Aryan side.”

3. For a discussion of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, see Israel Gutman, The Jews of Warsaw, 1939–1943: Ghetto, Underground, Revolt, trans. Ina Friedman (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1982); Barbara Engelking and Jacek Leociak, The Warsaw Ghetto: A Guide to a Perished City, trans. Emma Harris (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009).

4. SS-Oberführer Ferdinand von Sammern-Frankenegg (1897–1944) was the Police Leader (Polizieführer) of the Warsaw district on the eve of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Transferred to Croatia following his replacement by Jürgen Stroop in Warsaw, he was killed by Yugoslav partisans on September 20, 1944.

5. Jürgen Stroop (1895–1952) joined the Nazi Party and SS in 1932 and saw combat during the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. In 1942, as SS-Brigadeführer, Stroop commanded an SS garrison at Kherson before becoming the SS and Police Leader for Lemberg (now Lviv) in February 1943. Following his suppression of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in April 1943, he was dispatched to Greece as Higher SS and Police Leader. After difficulties with German civilian authorities there, he ended the war as commander of SS-Oberabschnitt Rhein-Westmark in the Rhineland. An American military court condemned Stroop to death in March 1947 for his role in the murder of downed Allied fliers within his jurisdiction but allowed him to be extradited to Poland to face trial for his crimes there, including the liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto. Jürgen Stroop was convicted of war crimes and executed in Warsaw on March 6, 1952.

6. See Jürgen Stroop, The Stroop Report, The Jewish Quarter of Warsaw Is No More! ed. and trans. Sybil Milton (New York: Pantheon Books, 1979).

The first major revolt of an urban population in German-occupied Europe, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising combined the valiant efforts of ghetto fighters with the dogged resistance of the general population. Many of those who engaged in armed resistance in Warsaw were adolescents in their teens; a majority of these came from the city’s active underground Jewish youth movements. Writing at the height of the insurgency, Oneg Shabbat chronicler Emmanuel Ringelblum noted that many of the bravest fighters were not men but young girls, who matched their male counterparts in courage, daring, and commitment. In his essay “Little Stalingrad Defends Itself,” Ringelblum reports that a Jewish teenager in Świętojerska Street had captured the public’s imagination as the Jewish Joan of Arc.

Document 9-1. Emmanuel Ringelblum, “Little Stalingrad Defends Itself,” c. April 1943, in Joseph Kermish, ed., “To Live with Honor and Die with Honor”: Selected Documents from the Warsaw Ghetto Underground Archives “O.S.” (Oneg Shabbath) (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1986), 601–3.

On the “Aryan side” there was intense interest in what was happening in the ghetto. It was related that the Germans were afraid to show themselves in the ghetto, and that they operated on burnt ground [i.e., scorched earth policy] only, moving forward by burning down block after block. The Germans were spoken of with contempt because of their atrocities. They were laughed at for not being able to put down a handful of Jews fighting for their honour. [. . .] There were rumours about Jews reconquering the Pawiak7 and releasing the prisoners there, who then joined the fighting. A story was spread in town about a handful of Jews who had captured a tank, got into it, and left the ghetto area. Popular fantasy also created a Jewish Joan of Arc. At 28 Świętojerska Street, the bristle workshop, a beautiful eighteen-year-old girl dressed in white had been seen firing a machine gun at the Germans with extraordinary accuracy, while she herself was invulnerable. [. . .] Among the rumours being spread on the “Aryan side” at that time there was a good deal of fantasy, but there were also authentic facts, if somewhat altered. The legend about the Jewish Maid of Orleans8 had its origin in the fact that Jewish girls took part in combat alongside the men. I knew these heroic girls from the period preceding the “action.” Most of them belonged to the Ha-Shomer Ha-Za’ir and Hechalutz [youth] movements. Throughout the war, they had carried on welfare work all the time with great devotion and extraordinary self-sacrifice. Disguised as “Aryan” women, they had carried illegal literature around the country, managed to get everywhere with instructions from the Jewish National Committee; they bought and transported arms, executed O.B.9 death sentences, and shot gendarmes and SS-men during the January “action.” Altogether they completely outdid the men in courage, alertness, and daring. I myself saw Jewish women firing a machine gun from a roof. Clearly one of these heroic girls must have distinguished herself in the heavy fighting waged by the O.B. at Świętojerska Street, and that was probably the origin of the story of the Jewish Maid of Orleans.

7. During the German occupation of Warsaw, Pawiak Prison served as the Gestapo’s largest political prison in occupied Poland and became synonymous with Nazi terror.

8. This is an appellation of Joan of Arc, whose greatest military success was the lifting of the Siege of Orleans against English forces in April 1429 during the Hundred Years’ War.

9. This is a common abbreviation of the Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa (Jewish Fighting Organization, or ŻOB). The ŻOB issued “death sentences” against those within the ghetto who collaborated with the Germans, including certain members of the Jewish Order Police.

The 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was the largest show of Jewish armed resistance in the course of World War II. The ŻOB and ŻZW, which instigated the insurgency, were two of the most successful manifestations of organized resistance, but they represented just the tip of the iceberg. Jewish underground organizations existed in over one hundred ghettos in German-occupied eastern Europe. Incredibly, under the most adverse conditions, Jewish prisoners also succeeded in forming resistance cells within the Nazi concentration camp system. During the late war years, surviving Jewish Sonderkommando units initiated uprisings at several extermination camps. On August 2, 1943, for example, Jewish prisoners rebelled at Treblinka, seizing firearms from their captors and setting fire to the camp. Some two hundred individuals escaped; half their number were soon recaptured and executed. Likewise, on October 7, 1944, Auschwitz prisoners assigned to maintain Crematorium IV in the Auschwitz II–Birkenau concentration camp rebelled when they learned that their unit was slated for killing. German guards and their auxiliaries brutally crushed the revolt, murdering several hundred prisoners, but not before the Sonderkommando succeeded in destroying Crematorium IV with homemade explosives, rendering it inoperable for the duration of the war.10

10. See Hermann Langbein, “The Auschwitz Underground,” and Nathan Cohen, “Diaries of the Sonderkommando,” both in Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp, ed. Yisrael Gutman and Michael Berenbaum (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press in association with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, 1994), 485–502 and 522–34; Gideon Graif, We Wept without Tears: Testimonies of the Jewish Sonderkommando from Auschwitz (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005).

The most successful uprising of its kind, however, took place at the Sobibór extermination camp. In the summer of 1943, transports of Jews from the General Government to the killing center grew fewer in number. Sensing that they might be murdered along with the last groups of deportees, the veteran Jewish Sonderkommando laboring at the extermination camp formed an underground resistance cell, led by Leon Feldhendler, a former Judenrat member from the nearby village of Zolkiewka. Feldhendler believed that the group’s best chance of survival was to escape the camp. He and his followers had witnessed many individual flight attempts, but experience had taught them that these invariably ended in the capture of the escaping prisoners and fierce retaliation on the rest of the camp population. Feldhendler convinced his colleagues that the solution lay in a mass escape from Sobibór. But how to organize a breakout that could provide all prisoners a chance to escape? In September 1943, a transport of Jews from Minsk brought to the camp first lieutenant Aleksandr (“Sasha”) Pechersky, a trained Soviet officer with combat experience. The resistance cell recruited Pechersky, asking him to mastermind an uprising that might free Sobibór’s six hundred prisoners.

On October 14, 1943, Pechersky’s plan came to fruition. At 4:00 p.m., Thomas (Tuvia) Blatt and a handful of his fellow prisoners cornered their first adversary, SS-Unterscharführer Josef Wolf, murdering him with an axe. Wolf was the first of eleven German and Ukrainian guards killed in the uprising. Other conspirators seized weapons and explosives. The facility’s electricity and phone wires were cut. Under a hale of SS fire, prisoners cut through the camp’s dense net of barbed wire and made a perilous dash through the minefields that encircled the camp.

By evening, half of the camp’s population, three hundred prisoners, had escaped. About one-third of these individuals were eventually recaptured and murdered. Those inmates who had remained behind during the uprising were also killed shortly before the liquidation of the camp some weeks later.11 Many of those still at liberty joined partisan units or received shelter and aid from sympathetic Poles. Nearly seventy prisoners who escaped Sobibór survived the war.12

11. Many of these were prisoners in Camp III, where, isolated from the main camp, they remained unaware of the uprising.

12. Among these individuals were Sasha Pechersky (1909–1990), Thomas (Tuvia) Blatt (1927–), and Leon Feldhendler (1909–1945). Feldhendler survived to see the July 1944 liberation of Lublin, where he and his wife had lived in hiding, but was murdered by members of an antisemitic Polish paramilitary group on April 2, 1945. For a discussion of the Sobibór revolt by eyewitnesses, see Dov Freiberg, To Survive Sobibor (Jerusalem: Gefen, 2007); Thomas Blatt, From the Ashes of Sobibor: A Story of Survival (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1997).

One of those survivors was Berel Dov Freiberg, just fourteen years of age when he was selected from a transport of Jews from Krasnystaw to labor in a Sonderkommando unit at Sobibór.13 A year later the teenage Freiberg served as a courier during the Sobibór uprising, keeping the individual actors in the revolt abreast of developments occurring in other parts of the camp. With his fellow prisoners, the fifteen-year-old participated in the killing of several German and Ukrainian guards before making his escape. In 1945, the youngster gave a dramatic account of the prisoner rebellion to Bluma Wasser, herself a survivor of the Warsaw ghetto and, with her husband, Hersh Wasser, a chronicler for the underground archival organization Oneg Shabbat.

13. For a more detailed discussion of the experiences of Berel Dov Freiberg and his arrival at Sobibór, see chapter 5.

Document 9-2. Oral history of Berel Dov Freiberg, recorded by Bluma Wasser, 1945, in Isaiah Trunk, ed., Jewish Responses to Nazi Persecution: Collective and Individual Behavior in Extremis (New York: Stein and Day, 1982), 283–87.

At exactly four p.m. Untersturmführer Neumann came to the tailors to have a uniform measured. He was received very warmly, told to sit down, and from behind, his head was split into two pieces with an axe and the halves were swept under the bunks. [. . .] At the exact same time, [Oberscharführer] Greshits, a Ukrainian, arrived at the shoemaker workshop, and in a second, he was turned into a corpse. Any German caught by the Jews was assassinated. If they came into the barrack to force us off to the labor sites, we thought to ourselves: “Briederke [brother], this won’t take long—you’ll be dead in no time.” We let them into the barracks and they never left again.

I ran from battle station to battle station as a courier, informing the units of our progress. We broke into the German compound and took all their arms, then headed for the administration office. [Scharführer] Beckmann was at his desk. He knew right away something was up because he’d just come from our barrack and found no one there, not even the [Oberscharführer], so he went straight back to the administration office, where we cut him off. He reached for his revolver, but there wasn’t a chance—all of us jumped him without guns and beat him dead because we didn’t want to shoot. The longer we kept things quiet the better off we’d be. It was hard to keep him down because he jerked around in wild death spasms. [. . .]

When everyone was already assembled inside the camp and we were getting ready to attack the arsenal, Zugwachmann Rel—how many times he’d beaten me!—suddenly appeared and realized something was happening when he saw the cut wires. The electricity and telephones were all put out of order by one of us who had access to the generators and smashed them. Rel asked us nervously: “Was gibt es Neues?” [“What’s up?”]. He just happened to be walking right in front of me, so I raised my axe and, along with two friends, chopped him up into little pieces.

Now everyone knew what was about to happen and a deafening cheer went up, shouts of “Vperyod!” “Vorverts!” “Foros!” [“Forward!”]. Our targets were now ahead of us, not behind us—the arms stockpiles! We stormed the arsenal, killed two Germans where they stood, and brought out the guns. All this time we could see nothing but bullet after bullet ripping at us from all sides—from the guard towers, from the Germans and the Volksdeutsche and the 300 Ukrainians who were shooting at us from all around, especially from the fourth camp. They were soon reinforced by another 150 Ukrainians who assaulted us with heavy automatic weapon fire. We returned fire with the few guns we had. But we didn’t keep static positions—we ran from station to station shooting in all directions, and defying the risk, broke out of camp. We were still at the wire perimeter when a youth beside me took a bullet and was left hanging on the wires. I was using a rifle I had gotten from the stockpile and kept on running. There were explosions all around—the mines went off, the bullets struck and flashed everywhere we went. The sound of men being torn to pieces, bullets shattering, and mines detonating thundered all through the area. Later, all we could do was laugh as we heard the rattling of the machine guns trailing off behind us. The shooting kept up all night and we got farther and farther away from the camp. We threw off everything along the way. [. . .]

After we ran several hours and were far from the camp by now, we counted ourselves up because everyone had run off in a different direction. There were twenty-four in our group. We kissed and embraced and couldn’t believe we were really outside the camp. We walked all night through the forest and found a good spot in a gorge grown over with thicket, and that’s where we rested. We didn’t eat all day because what we’d accomplished put us into such a state that we were all flushed from exhilaration and our blood was feverish and made us tremble. We couldn’t eat a bite and there was nothing to eat in the forest anyway. Someone had a piece of bread, a lump of sugar, so we shared it later.

The prisoner uprisings at Sobibór and subsequently at Treblinka were remarkable in that the rebellions struck at the very heart of the genocidal apparatus. Many escapees joined the ranks of partisan units, where they continued to defy Nazi military and occupation authorities. Jewish partisan bands operated extensively throughout Nazi-occupied Europe. Some twenty to thirty thousand Jewish fighters engaged in guerrilla warfare and sabotage against German forces and those who collaborated with them. These units faced tremendous obstacles in acquiring weapons, food, and shelter and were in constant danger of capture or denunciation by hostile elements within the local population. In eastern Europe, many Jews merged with the Soviet partisan movement, although they often faced discrimination or betrayal by antisemitic comrades in arms. As a result, many Jewish fighters preferred to maintain their own fighting organizations. One of the most successful of these partisan units combined traditional guerrilla activity with extensive rescue efforts. These were the Bielski partisans.14

14. See Nechama Tec, Defiance: The Bielski Partisans (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993).

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union, units of the Einsatzgruppen killed thousands of Jews in western Belorussia (now Belarus).15 Surviving Jews in the Nowogrodek District were confined in ghettos, principally in the towns of Nowogrodek and Lida. In 1942 and early 1943, German authorities liquidated these ghettos, murdering most of the region’s remaining Jewish population.

15. Western Belorussia had been Polish territory before World War II, but it had been annexed by the Soviet Union following the invasion of Poland by German and Soviet forces in September 1939.

The Bielskis were a family of millers and grocers residing in a farming region near the town of Stankiewicze. After a ghetto action in December 1941 in which their parents and other family members were murdered, the four surviving brothers—Tuvia, Alexander (Zus), Asael, and Aron—fled the Nowogrodek ghetto to the nearby forest and, with a handful of fellow escapees, formed the nucleus of a fledging Jewish partisan band. Familiar with the surrounding district, the brothers received arms and supplies from local non-Jewish friends and acquaintances. As their unit expanded, the Bielskis were able to augment their arsenal with captured German weapons and guns supplied by Soviet partisans.

Armed in this manner, the small band began to target and harass German troops and their collaborators operating in the region. Although paramilitary objectives were a major focus, the unit’s recognized leader, Tuvia Bielski,16 began to view as the group’s primary mission the rescue of Jews from the surrounding community. The Bielskis helped Jewish inhabitants of nearby ghettos to escape. Many Jews hiding in small family units also joined their ranks so that, by late 1942, the group had grown to over three hundred members.

16. Tuvia Bielski (1906–1987) emigrated with his third wife, Lilka (née Titkin), to Israel after the war, where he participated in the 1948 Israeli War of Independence. He and his family moved to Brooklyn, New York, in 1956. Bielski died in the United States in 1987; in 1988, his body was reburied with full military honors in Haar Hmnuchot in Jerusalem.

Such a large partisan group eventually attracted the attention of German authorities, and in the summer of 1943, occupation officials offered a bounty of one hundred thousand Reichsmark for information leading to the capture of Tuvia Bielski. Some twenty thousand German military and local auxiliary units were deployed to locate the Bielski band and to curb the growing partisan movement, composed of Soviet, Polish, and Jewish units, in the Belorussian forests.

In order to escape the German dragnet, the Bielski group, now seven hundred strong, moved in December 1943 to a new base in the swampy marshes of the Naliboki Forest, on the right bank of Nieman River. Here the band established an unlikely and remarkable community. A core group of 150 men—and a handful of women—engaged in armed operations on behalf of the group. Despite dissension within their own ranks from those who insisted that their unit should accept only armed and able-bodied fighters, Tuvia Bielski proved adamant in accepting all Jews who appealed to the group for aid. “To save a Jew is much more important than to kill Germans,” Tuvia told his men.17 As the armed fighters engaged German forces in defense of the unit, other members of the band cultivated arable land in the vicinity and foraged for food and supplies. The community ultimately established a bakery, laundry, and infirmary and set up an improvised synagogue, a tribunal to adjudicate disputes, and a makeshift jail. Some thirty children lived within the Bielski family group.18 The Naliboki base housed a school for adolescents, while a group of female members organized to supervise the youngest children.

In the summer of 1944, the Soviet army staged an offensive that swept the German Army Group Center back to the banks of the Vistula and liberated the greater part of Belorussia. Through the efforts of Tuvia Bielski and his comrades, an astonishing 1,236 Jews from the family camp had survived the war. At liberation, 70 percent of the group consisted of women, children, and the elderly, those individuals most likely to have perished during the German occupation.

Document 9-3. Members of the Bielski partisan family camp, including several small children, shortly before liberation, Naliboki Forest, Belorussia, 1944, USHMMPA WS# 77654, courtesy of the Yad Vashem Photo Archives.

The Bielski partisan movement represented the most successful rescue effort of its kind, but it was not the only instance in which Jewish partisans accepted and protected family units within their ranks. Rachmiel Łozowski was nine years old when he witnessed the killing of the Jews of Zhetl (Zdzięcioł), near Grodno in what is today Belarus in August 1942. As he and his family tried to flee the massacre, police officials apprehended his mother, two younger brothers, and sister, whom he never saw again. Rachmiel, his twelve-year-old brother, and his father were reunited after the raid and found their way to shelter in the Lipiczanska Puszcza forest. There they joined local partisans and lived in their family group for the next two years, surviving the war. In 1947 in Tel Aviv, Łozowski shared with historian A. Yerushalmi his experiences of a childhood spent among the partisan resistance.

Document 9-4. Oral history of Rachmiel Łozowski, Tel Aviv, 1947, USHMMA RG 15.084, Holocaust Survivor Testimonies, 301/540 (translated from the Yiddish).

The forest we were in was at Lipiczanska Puszcza. We stayed together as a family group. There were large partisan units all around us and they didn’t bother us. There were fifty people in our family unit, including five children. We would get food from peasants we knew. A teacher, Lazar Meir, used to take care of the children. He was also able to buy guns for the group. One time he left for the Lida [Ghetto] and came back with five Jews.

In the winter of 1943, fifteen other Jews and two children came to us. After that, still more and more people joined us. [. . .]

In the summer of 1944, the forests were put under siege by 32,000 Germans and Ukrainians. Partisan units pulled back. We hid out in underground bunkers. The starvation during that time was horrible. We used to get a few beans a day to eat. This went on for fourteen days. There was room for five people in our bunker—fourteen people lay down there during the siege. As a camouflage, we dragged two dead horses over to cover the entrance. When the Germans moved through with their hounds, the dogs bolted back from the stench. But we suffered terribly from those worm-eaten carcasses. The worms crawled all over us and we choked on the stink of death. We fainted from the putrid air.

Another time, we heard cavalry riding past followed by infantry. We thought they were Germans. We crawled out and started to run. My father was the only one to stay behind in the bunker. The “Germans” got him out and wanted to know who he was and what he was doing here. He told them he was part of a partisan family unit. All they did was yell at him for keeping a fire lit, then they left. They were partisans too, just like us. [. . .]

Sometimes the children would wander around outside the bunker. Once, two boys—Yosif and Srulik, aged seven and eight—and two little girls, aged four and five, fell into the hands of the Ukrainians. They shot the little girls dead right away and took the boys into the village gendarmes. The boys pleaded with the Ukrainians to let them go, but in vain. At that moment, grown-ups from our group passed by, and the boys started shouting: “See?! There go the adults!” The Ukrainians let go of the children and chased the grown-ups. The children got away and ran down into the bunker. Malke Shmulovitch fell into the Ukrainians’ hands. They led her into the village, raped her, cut out strips of her flesh, and poured salt into her wounds. She betrayed no one, though, and died heroically.

This is the way we suffered for such a long time. We always had knives ready at our sides, to take our own lives if we fell into the hands of the Ukrainians.

One day, Captain “Severny,” the Jewish Avreyml Shereshevski, came to see us to tell us the good news that the Red Army was near. I was the first one he met. I ran to tell the glad news to my people. I searched for them all day and finally found them. When I told them the news, they came back to life.

Unarmed Resistance: The Children’s War

Acts of armed resistance against Nazi and Axis oppression make up an integral chapter in the history of the Holocaust. Large-scale uprisings undertaken by Jewish underground organizations, such as those in the Warsaw and Białystok ghettos or in the Auschwitz, Sobibór, and Treblinka killing centers, demonstrated that Jewish populations did not go meekly like lambs to the slaughter, as some analysts have claimed, but openly defied German authorities and those who collaborated with them. For many Jewish communities in Nazi-occupied Europe, however, the constraints of captivity and the threat of brutal reprisals made armed resistance difficult and dangerous. Under such extreme conditions, most sectors of the Jewish population that wished to oppose Nazi persecution engaged in unarmed resistance. Such efforts included organized escapes of individuals to partisan units or to safe havens outside ghettos or camps, as well as the noncompliance of ghetto administrators, officials, and residents with Nazi decrees and the organization of educational, religious, and cultural activities prohibited by German authorities. While such actions posed no physical threat to their antagonists, they struck at the core of Nazi discriminatory policy.

In German-occupied Poland, the constellation of political and cultural organizations that had existed before the outbreak of World War II continued to function within the world of the ghetto. Because of the draconian measures imposed on ghettoized communities, many of these associations were driven underground, where they worked assiduously to counteract the effects of Nazi oppression. In the Warsaw ghetto, political parties and organizations were particularly active, and the clandestine publications they generated “multiplied like mushrooms in the rain,” noted Emmanuel Ringelblum, chief archivist of the Oneg Shabbat archive.19 The numerous youth organizations, a significant force in ghetto resistance activity, played an active part in these endeavors.

19. Joseph Kermish, “On the Underground Press in the Warsaw Ghetto,” Yad Vashem Studies 1 (1957): 85.

Those clandestine newspapers20 produced in the ghetto certainly did not match the standards of their organizations’ prewar publications. With printing materials in short supply, most news sheets were printed on carbon paper or lightweight flimsy paper.21 Many associations produced hectographed22 or typewritten editions, while others circulated handwritten copies. Few of the newspapers were very large. The majority was limited to a handful of pages—a dozen at most. Despite a perennial shortage of resources, these underground publications played an important role in the politics and civic life of the Warsaw ghetto. Their most essential task was to lift the flagging spirits of their readers and to strengthen their morale and will to resist Nazi oppression. Another unequivocal mission of the illegal press was to keep residents informed of events inside and outside the ghetto. Appearing in Polish, Yiddish, or Hebrew, underground newspapers and periodicals kept their readers abreast of wartime developments and the unparalleled atrocities leveled against Europe’s Jewish communities. In 1941 and 1942, many columns were devoted to speculation concerning the evolution of Nazi policy and to the acts of terror perpetrated by German officials against Warsaw’s incarcerated Jews. The clandestine press also focused on various aspects of ghetto life: economic conditions, employment issues, the activities of cultural and welfare institutions, and the policies of the Judenrat, about which most editors of the illegal press had little good to say. Largely socialist in orientation, underground newspapers were also sharply critical of the genuine social and class disparities that existed in the ghetto and railed against the measures of the Judenrat and other agencies that unfairly burdened the most impoverished sectors of the community.23

20. See Kermish, “On the Underground Press,” 85–123; Engelking and Leociak, The Warsaw Ghetto, 685–94.

21. This refers to an inferior-grade paper traditionally used for making multiple copies.

22. Hectography is a low-technology printing process involving the transfer of an original, prepared with special aniline inks, to a pan of gelatin or a gelatin pad pulled over a frame. Virtually obsolete in modern printing, the process is still used to produce temporary tattoos on human skin.

23. Kermish, “On the Underground Press,” 116ff.

Among the underground publishing organizations in the Warsaw ghetto, the clandestine youth press fulfilled a special need, encouraging young people to hold fast to their ideals in the face of Nazi persecution and offering spiritual and intellectual direction. The struggle against apathy, despair, and spiritual degeneracy proved a common goal among these newspapers and periodicals. Appropriate to their readers’ age and outlook, the underground youth press urged opposition to Nazi oppression and preparation for a Jewish future. Thus, publications such as the Polish-language El Al (Upwards) encouraged young audiences to take an active part in their community and to “look ahead to what the future may bring,”24 while others, such as Yunge Gwardie (Young Guard), a Yiddish news sheet, reminded youth active in resistance activities not to neglect their education and self-improvement. Dozens of underground newspapers were produced by young people for young people in the years 1941 and 1942, including Jungtruf (The Call of Youth), Di Yugent Stimme (The Voice of Youth), Avangarda Młodzieży (Youth Avant-Garde), and Płomienie (The Flame), the latter a publication of the Jewish defense organization Ha-Shomer Ha-Za’ir.

24. El Al, quoted in Kermish, “Underground Press,” 86.

The Gordonia youth organization sponsored three clandestine papers in the Warsaw ghetto: Oisdoier (Endurance), Z Problematyki ruchu w chwili obecnej (On the Present Problems of the Movement), and Słowo Młodych (Young People’s Voice). Before November 1941, when editor Eliezer Geller25 began to focus his attentions on older audiences, the latter publication targeted primarily youths in their middle and late teens. A Polish-language biweekly, Słowo Młodych was Gordonia’s mouthpiece, espousing the sentiments of that pioneering youth movement founded in Poland in 1925. Named for Aaron David Gordon (1856–1922), a proponent of Labor Zionism, Gordonia became an international movement in the late 1930s, promoting the creation of a Jewish homeland, the revival of Hebrew culture, and the preparation of youth for Aliyah to Palestine through education and vocational training. In the Warsaw ghetto, the Gordonia movement gained many adherents by promoting underground educational activities for its young members, comprising several age groups. Słowo Młodych spoke to the heart of its young readers, urging them to courageous action and to hopes for a brighter future. In an undated edition from the fall of 1941, Słowo Młodych urged its readers to ensure that they would not be the last generation of Jewish youth but rather “the first generation reborn to the Jewish nation.” The newspaper’s publishers invoked the Bible’s Eighty-third Psalm, “Keep Not Thou Silence, O God,” a lament for the nation of Israel traditionally interpreted as a prayer for the destruction of its enemies. As the Jewish people faced a new and terrible oppressor, the paper exhorted its young audience to courage.

25. Eliezer Geller (b. 1918) was a Gordonia activist and member of the ŻOB underground resistance in Warsaw. Geller led a unit of armed resistors during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising; on April 29, 1943, he succeeded in fleeing through the sewer system to the “Aryan side” of Warsaw. Taking refuge at the Hotel Polski, where German authorities interned Jews with foreign passports, Geller was discovered and ultimately transferred to Auschwitz, where he perished.

Document 9-5. “Let the Jewish Youth Remember,” Słowo Młodych (Young People’s Voice), Warsaw ghetto, spring, 1942, USHMMA, RG-15.070M, Zespół podziemie–prasa konspiracyjna [Clandestine Publications], 230/13/1.

Young People’s Voice

Let the Jewish youth remember that it is either the last generation of the dying wanderers of the desert, or the first generation of the Reborn Jewish Nation in Eretz Israel.

Psalm 83

Keep not Thou silence, O God: hold not Thy peace, and be not still, O God.

For, lo, Thine enemies make a tumult: and they that hate Thee have lifted up their heads.

They have taken crafty counsel against Thy people, and consulted against Thy hidden ones.

They have said, “Come and let us cut them off from being a nation; that the name of Israel may be no more in remembrance.”

O my God, make them like a wheel; as the stubble before the wind.

As the fire burneth a wood, and as the flame setteth the mountains on fire;

So persecute them with Thy tempest, and make them afraid with Thy storm.

Fill their faces with shame; that they may seek Thy name, O Lord.

Let them be confounded and troubled forever; yea, let them be put to shame, and perish:

That men may know that Thou, whose name alone is Jehovah, art the most high over all the earth.

Involvement in the clandestine youth press required a certain set of intellectual skills and abilities and remained the sphere of young people in their late teens and early twenties. Young children, by contrast, were of course limited in the kinds of resistance in which they could engage. In the ghettos of German-occupied Europe, however, there remained one kind of resistance activity for which their size and agility particularly suited them. The smuggling of foodstuffs and other essentials from the “Aryan side” was an illegal, but indispensable, component of ghetto life. It represented a vital source of food and supplies for the captive community, and many families lived on the resources that their members brought into the ghetto illicitly or the proceeds generated from selling smuggled goods. Very young children were especially well adapted for this perilous enterprise. Their diminutive forms enabled them to slip through small gaps and holes in the ghetto walls and to escape to municipal districts from which Jews had been proscribed. Once outside the ghetto, their youth often shielded them from the suspicion of German officials and local citizens so that they might safely beg, steal, barter, or purchase provisions for consumption in their incarcerated communities. Enterprising young smugglers often wore clothing with concealed inner pockets in order to return laden with half their weight in potatoes, bread, and other commodities.

Smuggling provided the sole means of survival for many families, and discouraging ghetto youngsters from such endeavors proved a difficult challenge, despite the best effort of child-welfare organizations. In his 1943 essay “Jewish Children on the Aryan Side,”26 Oneg Shabbat’s chief archivist, Emmanuel Ringelblum, recalled the case of a CENTOS administrator who tried to intercede on behalf of a group of orphaned smugglers who lodged together in the Warsaw ghetto. The youths earned up to fifty złoty per day through their exploits and had sufficient reserves of cash to set up in an apartment in the ghetto’s Mila Street. “When the CENTOS worker proposed that they move into a boarding school,” Ringelblum reported, “the children refused, declaring that they were managing very well by themselves. They said that the CENTOS should put starving children in the boarding schools.”27

26. Emmanuel Ringelblum, Polish-Jewish Relations during the Second World War, ed. Joseph Kermish and Shmuel Krakowski (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1974), 140–51.

27. Ringelblum, Polish-Jewish Relations, 149.

Ringelblum noted that the child smugglers he had seen possessed “the most extraordinary and fantastic courage.”28 The work was manifestly dangerous. Returning to the ghetto weighted down with contraband, the youths had little chance to escape potential captors, and many young “entrepreneurs” were intercepted with their heavy loads at ghetto exits or checkpoints. At the very least German officials or Jewish Order Police beat the youngsters mercilessly and seized their hard-won provisions. Many young smugglers paid with their lives for their efforts to bring food and necessities back to their starving community.

28. Ringelblum, Polish-Jewish Relations, 147.

Document 9-6. Arrested at a checkpoint, a Jewish boy holds a bag of smuggled goods, Warsaw ghetto, c. 1941, USHMMPA WS# 60611B, courtesy of the YIVO Institute.

One of Ringelblum’s Oneg Shabbat colleagues, Henryka Łazowertówna, helped to immortalize these everyday heroes who risked life and limb to convey food and supplies to the Warsaw ghetto. During the “Great Deportation” action of July 1942, Łazowertówna voluntarily joined her mother at the Umschlagplatz and was deported to her death at Treblinka.29 In the preceding year, however, her poem “The Little Smuggler” had already been set to music and become a popular ballad among ghetto inhabitants.

29. Samuel D. Kassow, Who Will Write Our History? Emmanuel Ringelblum, the Warsaw Ghetto, and the Oyneg Shabes Archive (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007), 182.

Document 9-7. Henryka Łazowertówna (Lazowert), “The Little Smuggler,” Warsaw ghetto, c. 1941, in Michał Borwicz, ed., Pie´s´n ujdzie cało: Antologia wierszy o z·ydach pod okupacja˛ niemiecka˛ (Warsaw: Centralna Z·ydowska Komisja Historyczna w Polsce, 1947), 115–16 (translated from the Polish).

The Little Smuggler (a Song)

Through walls, through holes, though sentry points,

Through wires, through rubble, through fences:

Hungry, daring, stubborn

I flee, dart like a cat.

At noon, at night, in dawning hours,

In blizzards, in the heat,

A hundred times I risk my life,

I risk my childish neck.

Under my arm a burlap sack,

On my back a tattered rag;

Running on my swift, young legs

With fear ever in my heart.

Yet everything must be suffered;

And all must be endured,

So that tomorrow you can all

Eat your fill of bread.

Through walls, through holes, through brickwork,

At night, at dawn, at day,

Hungry, daring, cunning,

Quiet as a shadow I move.

And if the hand of sudden fate

Seizes me at some point in this game,

It’s only the common snare of life.

Mama, don’t wait for me.

I won’t return to you,

Your far-off voice won’t reach.

The dust of the street will bury

The lost youngster’s fate.

And only one grim thought,

A grimace on your lips:

Who, my dear Mama, who

Will bring you bread tomorrow?

The following photographs (Documents 9-8 and 9-9) are wrenching and arrest the eye instantly. Well known to students of World War II, the images portray one of the first public executions of resistance members by Wehrmacht soldiers following the German invasion of the Soviet Union. On October 26, 1941, members of the German 707th Infantry Division hanged twelve members of the communist underground near or on the grounds of a yeast factory in Minsk, Belorussia. The condemned were executed in groups of three. The Lithuanian collaborator tasked with recording these events presumably photographed only one of the proceedings in its entirety, near the gates of the old factory works. The first in the series of images he captured that day shows German and Lithuanian troops of the 707th parading three of the captive resistance figures through the streets of Minsk to the execution site. One of the prisoners, a young woman, commands attention. Around her neck she wears a placard reading in German and Russian, “We are partisans and have shot at German soldiers.”

Document 9-8. Historians believe the girl in the center of the photograph to be teenage resistance member Masha Bruskina, being marched with her comrades Kiril Trus and Volodya Shcherbatsevich to their place of execution by German soldiers, Minsk, October 26, 1941, USHMMPA WS# 14101, courtesy of the Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1972-026-43.

The young girl is believed to be seventeen-year-old Masha Bruskina,30 born in Minsk in 1924 to a Jewish family. Shortly after the German occupation of the Belorussian capital in late June 1941, she moved with her mother into the Minsk ghetto. The teenage Masha was, however, a communist and soon escaped to the city’s “Aryan side,” lightened her hair, and took on her mother’s maiden name, Bugakova, to avoid detection. The young woman volunteered as a nurse at the hospital attached to the city’s polytechnical institute, which occupying German forces had requisitioned as an infirmary for wounded Soviet prisoners of war. Perhaps at this juncture Masha joined a local resistance cell organized by Kiril Trus and Olga Shcherbatsevicha. The teenager used her post at the hospital to smuggle to the Soviet underground medical supplies and photographic equipment, the latter instrumental in creating false identity papers and other forged documentation. With her aid, other resistance members were able to remove Soviet prisoners of war to safety and to redeploy captured Soviet officers with significant combat experience to the ranks of the growing partisan movement. Despite the inscription on the placard she wore on the day of her death, Masha was not involved in armed resistance. At this time, such efforts were almost wholly the province of male members of the fledgling Belorussian resistance, while females functioned principally as couriers of supplies and information.

30. See Nechama Tec and Daniel Weiss, “A Historical Injustice: The Case of Masha Bruskina,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies 11, no. 3 (winter 1997): 366–77.

In early October 1941, a Soviet prisoner-patient denounced the resistance group to German authorities. Masha and several members of her cell, including leaders Kiril Trus and Olga Shcherbatsevicha, as well as the latter’s sixteen-year-old son, Volodya Shcherbatsevich, were arrested. All, including Masha, were brutally beaten and tortured, but none would give the names of fellow resistance members.

On October 26, 1941, Masha, with Kiril and Volodya, walked together with their German and Lithuanian captors to the gates of the yeast factory near Karl Marx Street, the chosen place of execution. Those citizens who observed her that day remarked upon the calmness of the three condemned and the quiet courage and self-possession of the teenage girl.31 Masha was chosen as the first victim. With her hands tightly bound, the young girl stepped onto a chair, aided by one of the soldiers, while a German officer adjusted the noose about her neck. In one of the extant photographs of the event, the teenager turned her back to the crowd. “When they put her on the stool,” recalled eyewitnesses Petr Pavlovich Borisenko, “the girl turned her face towards the fence. The executioners wanted her to stand with her face to the crowd, but she turned away and that was that. No matter how much they pushed her and tried to turn her, she remained standing with her back to the crowd. Only then did they kick away the stool from under her.”32

31. See the testimony of Nina Antonovna Zhevzhik, reprinted in Tec and Weiss, “A Historical Injustice,” 367–68.

32. Petr Pavlovich Borisenko, quoted in Lev Arkadiev and Ada Dekhtyar, “The Unknown Girl: A Documentary Story,” Yiddish Writers’ Almanac 1 (1987): 187.

Document 9-9 portrays the young girl directly after her hanging. Her comrade, sixteen-year-old Volodya Shcherbatsevich, weeps at the sight of his dead friend, as a German officer tightens the noose about his neck.

Document 9-9. The hanging of teenage resistance figures, believed to be Masha Bruskina and Volodya Shcherbatsevich, by an officer of the German 707th Infantry Division, Minsk, October 26, 1941, USHMMPA WS# 25136, courtesy of Ada Dekhtyar.

The photographs became public in the immediate postwar period and soon became iconic images of the Great Patriotic War, as the Soviet partisan resistance movement came to be known. The two men in the photos were quickly identified, but the identity of the “unknown girl” remained a mystery for years to come. Many historians now believe the teenage female in the photographs to be Masha Bruskina, based on extensive documentary evidence and identification by contemporary eyewitnesses, family members, and friends.

In Hiding

When war began in Europe in September 1939, some 1.6 million Jewish children lived in those areas that would fall under the control of Nazi Germany and its allies. Historians estimate that as many as 1.1 million youngsters died in the Holocaust. The small percentage of young people who survived the genocide did so in part because they were the focus of rescue efforts by individuals, religious institutions, welfare agencies, and resistance organizations that sought to save Jews—especially Jewish children—from Nazi persecution. Many thousands survived because their rescuers concealed them in their own homes or because a dense network of supporters protected and sustained them.33

33. For a discussion of hidden children, see Howard Greenfeld, The Hidden Children (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1993); Andre Stein, Hidden Children: Forgotten Survivors of the Holocaust (Toronto: Penguin Books, 1994); Ewa Kurek, Your Life Is Worth Mine: How Polish Nuns Saved Hundreds of Jewish Children in German-Occupied Poland, 1939–1945 (New York: Hippocrene Books, 1997); Mordecai Paldiel, “Fear and Comfort: The Plight of Hidden Children in Wartime-Poland,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies 6, no. 4 (1992): 397–413.

Jewish children faced exceptional challenges when they went into hiding. Some youngsters could pass as non-Jews and lived openly with their rescuers. In these circumstances, obtaining falsified identity papers, often purchased on the black market or provided by members of the underground resistance, was crucial. By acquiring forged papers, such children might have access to legitimate documentation from local authorities as well as to food and clothing ration coupons, essential for survival in Nazi Germany or its occupied territories. A hidden child’s safety depended on strict secrecy. Rescuers often needed to invent elaborate fictions in order to justify the child’s presence in their household, explaining to neighbors that the youngster was a distant relative or a refugee from a distant town or village. It was essential that the child adapt swiftly and completely to his new identity and environment. Young people learned to answer by their fictive name without fail and to avoid any language or mannerisms that might be considered “Jewish” or foreign. As most Jewish children were hidden by individuals or religious institutions that embraced faiths different from their own, youngsters carefully learned to recite the prayers and catechism of their “adopted” religion in order to avert the suspicions of both adults and peers. One false word or gesture was sufficient to place both the child and his or her rescuers in jeopardy.

Of course, there were children who could not pass as “Aryans” or live openly with their protectors. Many youngsters had classical “Jewish features” or had spoken only Yiddish at home, and thus spoke the local language imperfectly or with a telltale accent. Others had lived in the immediate area before ghettoization or deportation had taken place and feared that former neighbors and acquaintances might recognize them. These children remained physically concealed for a significant portion, or for the entirety, of their time in hiding. In rural settings, such youngsters might live out the war in barns, root cellars, or farm outbuildings. In urban areas the risks were greater, so rescuers might conceal their young charges in attics, cellars, closets, or wardrobes, away from prying eyes. Youngsters often had to remain silent or even motionless in their hiding places for hours at a time. Both children and their protectors lived in constant fear lest a raised voice or a footfall should arouse the suspicion of their neighbors. While children with an “Aryan appearance” might continue their education and find companionship among school-age friends, children in complete concealment had no such options and spent interminable hours alone, often in uncomfortable quarters, without occupation or human interaction. Like their coreligionists living openly with foster families, clandestinely concealed children often moved from one hiding place to another to ensure the safety of both the rescuers and their charges. Some hidden children lived with their families; for others, life in hiding meant long separation from loved ones, a division that tormented both children and their parents.

Through his work as the chief archivist of the underground archive Oneg Shabbat, Emmanuel Ringelblum observed the minute workings of the Warsaw ghetto. In an essay in 1943, he chronicled the daily challenges faced by children hiding with family members or rescuers on Warsaw’s “Aryan side.”

Document 9-10. Emmanuel Ringelblum, “Jewish Children on the Aryan Side,” 1943, in Emmanuel Ringelblum, Polish-Jewish Relations during the Second World War, ed. Joseph Kermish and Shmuel Krakowski (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1974), 140–45.

Jewish families rarely crossed to the Aryan side together. First the children went, while the parents stayed on in the ghetto in order to mobilize the necessary funds for staying on the Aryan side. Very often the parents gave up the idea of going across to the Aryan side, as they did not have the money to fix up the whole family. The cost of keeping a child on the Aryan side in the summer of 1942, when the number of children being sent over was at its peak, was very high, about 100 złoty a day. A sum was demanded for six months or a year in advance, for fear that the parents might be deported in the interim. Thus, a sum of several tens of thousands of złoty was required to fix up a child on the Aryan side and only very wealthy people could afford to do so. Parents of limited means and especially working intellectuals were forced to see their children taken as the first victims in the various “selections” and “actions.” Not all Jewish parents wanted to send their children to the Aryan side. There were those who weighed the question of survival for the children, especially the youngest ones, when no one knew what would happen to the parents at the next “selection.” Some parents argued that a child deprived of its parents’ care will wither like a flower without the sun. There were children who strongly opposed being sent to the Aryan side. They did not want to go to the other side alone, but preferred to die together with their parents. [. . .]

The majority of children, however, agreed to go across to the Aryan side, as living conditions in the ghetto were terrible. They were not allowed to leave their flats, they stayed for whole weeks in stuffy, uncomfortable hide-outs, they did not see daylight for long months. No wonder then that they let themselves be tempted by the promise of going out into the street, of walking in a garden, etc., and agreed to go to the Aryan side by themselves.

I know an eight-year-old boy who stayed for eight months on the Aryan side without his parents. The boy was hiding with friends of his father’s, who treated him like their own child. The child spoke in whispers and moved as silently as a cat, so that the neighbors should not become aware of the presence of a Jewish child. He often had to listen to the anti-Semitic talk of young Poles who came to visit the landlord’s daughters. Then he would pretend not to listen to the conversation and become engrossed in reading one of the books which he devoured in quantities. On one occasion he was present when the young visitors boasted that Hitler had taught the Poles how to deal with the Jews and that the remnant that survived the Nazi slaughter would be dealt with likewise. The boy was choking with tears; so that no one would notice he was upset, he hid in the kitchen and there burst out crying. He is now staying in a narrow, stuffy hideout, but he is happy because he is with his parents.

The situation is much worse for the children who have lost their parents, who were taken away to Treblinka. Some of their Aryan protectors have meanwhile taken a liking to the children and keep them and look after them. But these are only a small percentage of the protectors, generally people of limited means in whom Mammon has not yet killed all human feeling. People like these have to suffer on account of the Jewish children, but they do not throw them out into the street. The more energetic among them know how to fix themselves up and receive money subsidies from suitable social organizations. We know of cases where the governesses of wealthy children took care of them after their parents had been taken away to Treblinka. They keep these children out of their beggarly wages and don’t want to leave them to their fate. Some of these Jewish orphans were fixed up in institutions, registered as having come from places affected by the displacement of the Polish population (Zamo´s´c, Hrubies´zow, Pozna´n, Lublin, etc.). A considerable percentage of the orphans returned to the ghetto, where the Jewish Council fixed them up in boarding schools; they were taken away in the “resettlement actions.” There were frequent instances, when the “protectors,” having received a large sum of money, simply turned the child out into the street. There were even worse cases where the “protectors” turned Jewish children over to the uniformed police or the Germans, who sent them back to the ghetto while it was still in existence.

There were also cases of Jewish children, especially very small children, who were adopted by childless couples, or by noble individuals who wanted to manifest their attitude to the tragedy of the Jews. A few Jewish children were rescued by being placed in foundling homes, where they arrive as Christian children; they are brought by Polish Police, who, for remuneration of course, report them as having been found in staircase wells, inside the entrances to blocks of flats, etc.

There were no problems with Jewish children as far as the need for keeping their Jewish origin secret. In the ghetto Jewish children went through stern schooling for life. [. . .] They ceased to be children and grew up fast, surpassing their elders in many things. So when they were sent to the Aryan side, their parents could assure their Aryan friends and acquaintances that their little daughter or son would never breathe a word about his Jewish origin and would keep the secret to the grave. I know of a young girl who was dying in an Aryan hospital, far from her parents. She kept the secret of her origin till her death. Even in those moments of the death agony, when earthly ties are loosed and people no longer master themselves, she did not betray herself by a word or the least movement. When the nurse who was present at her death bed called her by her Jewish name, Dorka, she would not reply, for she remembered that she was only allowed to respond to the sound of the Aryan name, Ewa.

Even the youngest children were able to carry out their parents’ instructions and conceal their Jewish origin expertly. I remember a four-year-old tot who replied to my asking him treacherously what he was called before—a question often put to children by police agents—by giving his Aryan name and surname and declaring emphatically that he never had any other name.

Hidden children often spent anguished weeks and months away from their parents. Szepsel Griner, born shortly before the outbreak of World War II, became separated from his family in the early years of the German occupation of Poland. Presumably because Szepsel was the youngest child, his father placed the toddler with a Polish farmer before relocating his wife and remaining children to a hiding place in the home of an acquaintance. Szepzel’s father visited him daily, bringing his son toys and provisions, and it was from him that the small boy learned of the deportation and murder of his mother and siblings. After a time, the elder Griner stopped coming to the farm, and Szepzel came to understand that his father had been killed. Following the liberation of Zamoś´c by Soviet forces, the youngster spent a year in a Polish orphanage. Discovered at the home by his nineteen-year-old cousin, Szepsel was adopted by an aunt who had been living in Russia. In the immediate postwar period, the young boy related his experiences in hiding to an official of the Jewish Historical Commission in Warsaw.

Document 9-11. Oral history of Szepsel Griner by the Central Jewish Historical Commission in Poland, c. 1947, USHMMA RG 15.084, Holocaust Survivor Testimonies, 301/2284 (translated from the Polish).

Statement 35

Szepsel Griner, eight years old, born in Zamoś´c. Before the war he lived in Zamoś´c. During the occupation in Zamoś´c. Currently he lives in Wałbrzych 1-Maja 4:

When the German marched into our area, a man knocked on our window and called to Papa to flee. Papa took some clothes with him and fled to a German acquaintance. We—that is, I, Mama, my sister and two brothers, as well as my uncle—were supposed to follow.

Once, as we sat in our hiding place, the Germans came to take us away, but our German defended us. He said he would not deliver us up, and they had to go away empty-handed. We stayed there hidden for ten days.

Papa lodged me with a Polish woman, and he himself went to find another hiding place. He found an empty room at someone’s home. He prepared a lot to eat there and brought Mama, my sister, and my brothers there. After four weeks they were discovered by the Germans and brought to a camp. Mama was sick. The Germans came to the camp, and Papa understood that they wanted to kill all the Jews, so he fled, but my sister and my brothers didn’t manage to get away. The Germans took them, deported them, and killed them. Papa came to me and told me all of that. At first he didn’t want to tell me any of this, but I saw that he was so sad, and I cried constantly that I wanted to go to Mama. So he told me everything. Papa came to me daily. Every time he brought vodka for the Pole and other things with him. He said to me that I should be good, mind the Pole, and not wander out upon the farm.

Papa brought me a revolver (a play one), a harmonica, and other toys. The whole day I played the harmonica.

In the shed next to me the farmer kept rabbits, which I liked to play with.

At night I cried often. I was so sad, I wanted so badly to have someone from among my relatives with me.

I had completely lost my appetite and I got very bad food to eat besides. For a long time, Papa didn’t come anymore to me. This is when I understood that the Germans had killed Papa too.

Once I sat in the house and looked out the window. I saw that many Jews with children were being led away. Some of them didn’t have any hands. Where they were brought to, I don’t know.

I always felt as if I were going to burst into tears, but I only cried when no one was in the house, or at nights.

Later, the Russians started throwing bombs, and soon they also came to us.

During World War II, thousands of Jewish children were concealed by conscientious individuals, by religious and resistance groups, and by various aid and relief organizations dedicated to helping Jews and other persecutees escape from harm in areas controlled by Nazi Germany and its allies. In most cases, hidden children lived with their rescuers or in a series of safe houses, isolated from friends and loved ones. Yet the Shoah’s most famous hidden child did not suffer her long ordeal alone but lived in concealment with her family, aided and insulated from deportation by a network of friends and supporters. That youngster was, of course, Anne Frank, whose diary has captured the imagination of generations of young readers and personalized the fate of hundreds of thousands of children murdered in the Holocaust.

Annelies (Anne) Frank was born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, on June 12, 1929, the second daughter of prosperous businessman Otto Frank, and his wife, Edith. Immediately after Hitler’s rise to power, Anne fled with her parents and elder sister, Margot, to Amsterdam in the Netherlands. The Franks had hoped to escape antisemitic persecution in their native Germany, but when German forces invaded Dutch territory, the family once again figured as targets of Nazi anti-Jewish policy. When Margot Frank received a summons for deportation on July 5, 1942, Otto Frank convinced his family to go into hiding. On the following day, the family entered a narrow, three-story annex attached to Frank’s Opetka office building at 263 Prinsengracht34; the family would not leave it again until their arrests two years later. The vivacious Anne had just received a plaid-covered autograph book for her twelfth birthday and now began to use the volume as her diary, keeping a faithful and detailed account of events as they took place in the “secret annex.” Addressing her entries to “Dear Kitty,” a favorite character in a book series that she had been reading, the young Anne captured a portrait of a family in hiding; she also vividly portrayed a young girl growing up under desperate circumstances. Among the individuals introduced in her journal were the van Pels family and Fritz Pfeffer, friends or acquaintances who eventually joined the Frank family in their hiding space,35 and the groups’ rescuers, including Miep Gies and Viktor Kugler, Otto Frank’s former employees, who brought food, supplies, and information and ensured the hidden Jews’ safety during their confinement. In March 1944, while listening to Radio Oranje, a Dutch resistance radio station, Anne heard a broadcast by Gerrit Bolkestein, education minister within the Dutch government in exile. Bolkestein announced that he would make a public record of the Dutch population’s experiences during World War II and asked his countrymen to save their letters and journals for collection in the postwar. At this point, Anne began composing and editing her diary with future publication in mind. She continued writing until August 1, 1944.

34. Otto Frank had owned two businesses in Amsterdam that produced and sold pectin and other food preservatives and spices. After Nazi German forces overran the Netherlands, Frank was forced to liquidate his assets. He transferred the ownership of the businesses, including Opetka, to trusted colleagues so that he could continue to make sufficient income for his family and might recover his assets in the postwar period.

35. Anne Frank gave pseudonyms to fellow dwellers in the annex who were not members of her immediate family. The van Pelses received the fictive name “van Daan,” while the dentist Fritz Pfeffer became “Albert Dussel.”

This diary entry would be her last. Three days later, on August 4, 1944, members of the SS and Dutch Green Police discovered the Franks’ hiding place and arrested its inhabitants. Anne, her family, and the friends who had been concealed with them were transferred to the Dutch transit camp Westerbork, then on September 3 to Auschwitz. Sometime in October 1944, Anne and Margot arrived on a transport from Auschwitz to the Bergen Belsen concentration camp. Both succumbed to typhus there in late February or early March 1945, just weeks before the liberation of the camp by British forces. The sole survivor of the group in hiding, Otto Frank,36 returned to Amsterdam in the summer of 1945. There he recovered his daughter’s diary and papers, which had been retained by Miep Gies. Anne’s diary appeared in print for the first time in Dutch in 1947 and has been in publication ever since.37

36. Hermann van Pels was gassed shortly after arrival at Auschwitz, where Edith Frank died of starvation in January 1945. Fritz Pfeffer perished in Neuengamme concentration camp in December 1944. Peter van Pels, Anne’s love interest, survived until the last days of the war, dying of exhaustion at Mauthausen on May 5, 1945. Mrs. van Pels joined Margot and Anne briefly at Bergen Belsen and probably died shortly thereafter on a transport bound for Theresienstadt.

37. For a further discussion of Anne Frank and the influence of her diary, see Anne Frank, The Diary of Anne Frank: The Revised Critical Edition, ed. David Barouw and Gerrold van der Stroom, trans. Arnold J. Pomerans, B. M. Mooyaart-Doubleday, and Susan Massotty (New York: Doubleday, 2001); Hyman Aaron Enzer and Sandra Solotaroff-Enzer, eds., Anne Frank: Reflections on Her Life and Legacy (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000).

Two days before Anne Frank wrote the last lines in her journal, another young girl in Amsterdam, Louise Israels, was celebrating her second birthday in hiding. She had been born on July 30, 1942, in the Dutch city of Haarlem, where she lived with her parents, grandparents, and elder brother. The Israelses were a secular and assimilated Jewish family. Louise’s father, a reserve officer with the Dutch army, worked in the family business selling women’s lingerie and accessories. Although the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands had imposed a number of antisemitic measures and restrictions upon the Jewish population, the Israelses, like many Dutch Jews, hoped that their little family might emerge from the war years intact. Two events shook their confidence. In early March 1943, in a bold and imaginative move, the Dutch national resistance bombed the central population registry office in Amsterdam, effectively hindering German authorities from comparing forged personal documents held by Jews and other persecutees in Holland against authentic public records. Nazi officials countered this measure with a series of brutal reprisals. In Haarlem, Nazi occupiers arrested the Israelses’ neighbor, the president of the city’s Jewish community, and shot him and nine other prominent Jews before the eyes of their fellow citizens. At the same time, the Jews of Haarlem received a summons to concentrate in Amsterdam as a prelude to deportation. Spurred by these events, Louise’s father devised a daring plan to save his family. First, he secured false papers for his wife and children from the Dutch underground. Then, liquidating all available assets, Israels located a small apartment near the city’s famous Vondelpark and paid the leasing agent funds sufficient for ten years’ rent.

Sometime in the spring months of 1943, the young family slipped quietly inside the doors of their new residence. They would not emerge again until the arrival of Allied forces in Amsterdam two years later. Joining the Israelses in hiding was a young woman named Selma, the daughter of the president of Haarlem’s Jewish community who had been murdered just weeks before. Her family had been deported following her father’s death, and the young woman now became an integral part of the Israels family. She would prove a valuable source of information when a maturing Louise Israels began to piece together her wartime experiences.

Unlike the more famous Frank family, who lived in a secret annex, the Israelses literally hid in plain sight, lodged in a residential apartment building amid dozens of neighbors. It was a perilous existence in which the threat of denunciation was an ever-present reality. The family lived in a silent world, isolated from the vibrant city outside. After dark, Louise’s father risked a nighttime curfew to provide his family with food and firewood. Israels’ army reserve comrades represented a vital lifeline for the little household, regularly bringing them provisions and news from the outside world.

In the summer of 1944, the family had been living in hiding for more than one year. Although their situation was certainly preferable to that of thousands of Dutch Jews awaiting deportation in transit camps such as Westerbork and Vught, the family knew hunger and privation and lived in constant fear lest a raised voice or obtrusive noise should rouse the suspicion of their neighbors. So, when little Louise’s second birthday arrived on July 30, 1944, her parents decided to use the event to lift the family’s morale. In a photograph from that day, Louise wears a new dress for her party, which her mother made from an old blouse. She is perched on a rattan doll’s chair that her father purchased through Dutch friends “on the outside.” Her nurse, Selma, cobbled together old scraps to make a rag doll, which Louise clutches wistfully. For the occasion, her elder brother has lent her his favorite pull-toy horse, a special treat—but just for the day!38

38. Information concerning the story of the Israelses’ years in hiding is provided courtesy of Louise Lawrence-Israels.