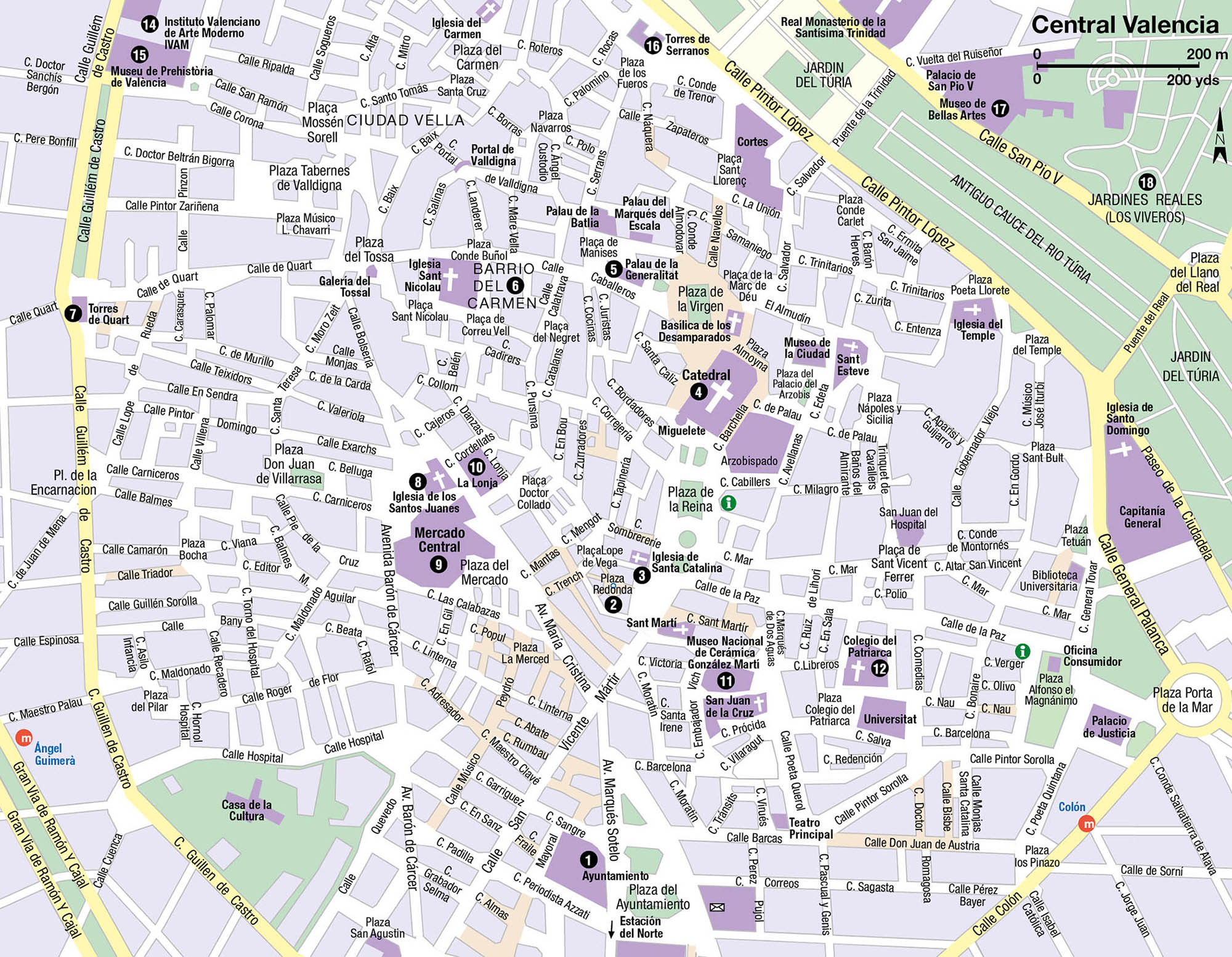

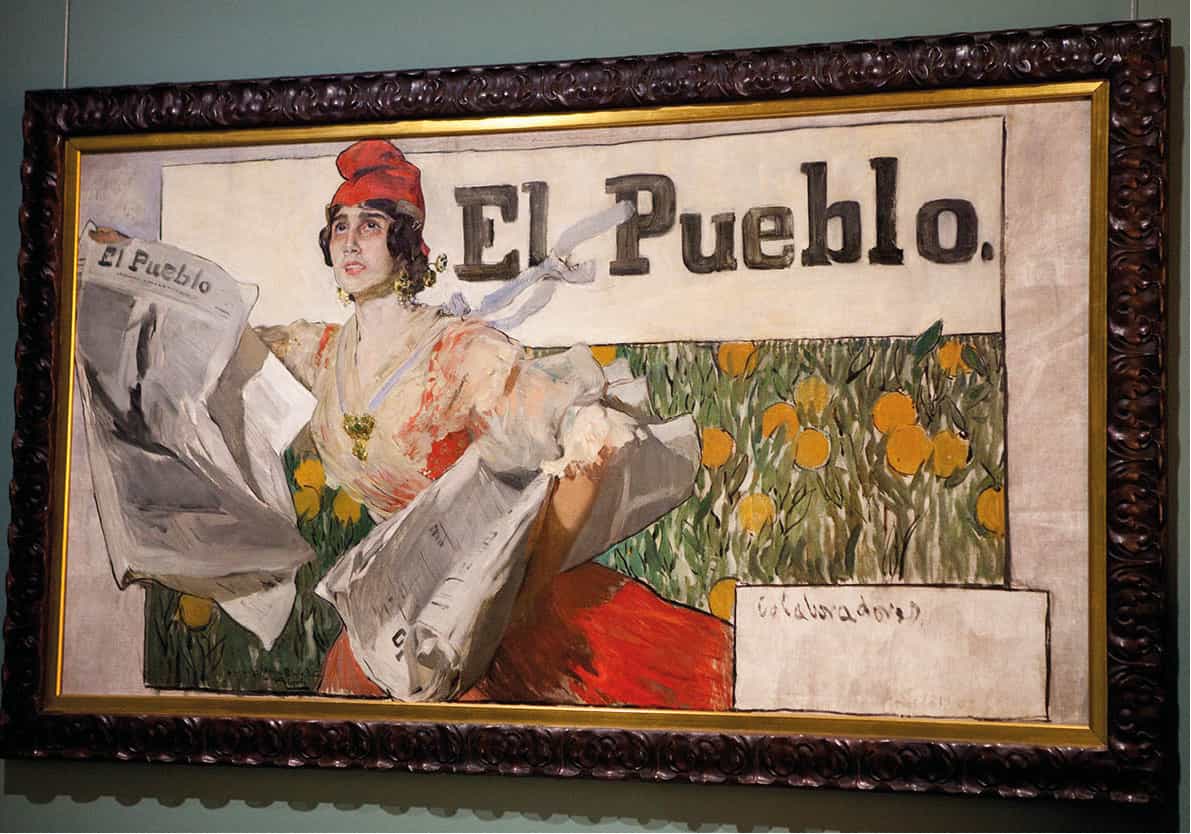

The city centre, bordered to the north by the dry bed of the River Turia, to the south by the railway station and to the east and west by broad avenues, is compact enough to walk around. Most of the major sights are contained within this area. The fine arts museum and Los Viveros gardens, however, are on the far bank of the Turia but still within easy reach of the centre on foot. To travel further afield there is an efficient bus network and a metro system which connects with a modern tramway to the beach. Another option is to hire a bike (for more information, click here) and take advantage of the city’s flat terrain and network of cycle lanes.

Santiago Calatrava’s stunning Palau de les Arts

iStock

Street names

Many streets and squares in Valencia have two versions of their name, in the Valencian language and in Spanish (Castilian). Also, some squares have changed their names within living memory and locals often still refer to them by their former names.

City centre

Whether or not you arrive by train, a good place to begin a tour of Valencia is the mainline railway station, the Estación del Norte. Built between 1907 and 1917 in a style inspired by Austrian art nouveau, it is far more than a mere transit terminal; this is a celebration of the agricultural abundance of Valencia. Its twin white towers are hung with bunches of sculpted oranges. Inside there are yet more oranges, this time in stained glass. In the foyer and cafeteria, meanwhile, are ceramic murals depicting the life and crops of the huerta, the farmland around Valencia.

Over the road from the station is the 19th-century Plaza de Toros, four floors of 384 identical brick arches making a structure reminiscent of a Roman amphitheatre and with seats for 17,000 people. The bullfights here during the Fallas festival in March constitute the first of the official season. Next to it, in Pasaje Doctor Serra, is one of the oldest bullfighting museums in Spain, the Museo Taurino (www.museotaurinovalencia.es; Tue–Sat 10am–7pm, Sun and holidays 10am–2pm).

Plaza del Ayuntamiento

From the station it is only a short walk to the triangular main square, the Plaza del Ayuntamiento. Laid out in the 1920s, it has had four names during its short history. During Franco’s time it was known in his honour as the Plaza del Caudillo but after his death, the citizens of Valencia were quick to remove the name and the statue of their defunct leader mounted proudly on a horse.

The town hall in the Plaza del Ayuntamiento

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The city’s symbol

In front of the city hall, at the base of the clock tower, is a statue of the city’s coat of arms held by two naked females and surmounted by a bat. The bat (rat penat in Valencian, meaning ‘winged rat’) has been Valencia’s symbol since the 13th century. In 1238, while Jaime I of Aragón was going about the business of conquering Moorish-held Valencia, a bat is supposed to have perched on his helmet. This was seen as an omen of good fortune and, ever since then, the bat has been retained as a symbol of the city.

The main building presiding over the square is the Ayuntamiento 1 [map], the city hall (Mon–Fri 8am–3pm except on days of official functions; www.valencia.es; free), an ornate palace of municipal authority which is essentially two buildings in one. First came a convent-like girls’ school, founded in the 19th century by the archbishop of Valencia. To this was added a dignified civic palace distinguished by its twin domes on the corner, a clock tower and a large ceremonial balcony placed in the middle. At the tower’s base stand a statue of the city’s coat of arms, and four statues representing Prudence, Fortitude, Justice and Temperance. Inside the city hall there is a handsome marble staircase, ornate council chamber and reception room, and municipal museum (open on weekdays 8am–2pm).

Across the square is the post office with sculpted angels, representing the speed of modern communications, hovering over its façade. The letter boxes at ground level are in the form of snarling bronze lions’ heads.

If the centre of the square between these two buildings seems a little devoid of interest except for its flower stalls, it is because it is kept as a public space for fiestas. In particular, during the Fallas festival (for more information, click here), when the largest of the city’s combustible works of art is erected here. Before and during the Fallas, the square is also used as the setting for a mascletà, a peculiarly Valencian tradition of letting off firecrackers in synch in broad daylight with the aim not of making pretty visual effects but of creating a deafening but – or so Valencians think – harmonious din.

Plaza de la Reina and Plaza Redonda

Continue out of the square via its apex, walking in the same direction in which you arrived, and you will join Calle San Vicente Mártir. This leads you towards the second most important square, the Plaza de la Reina. On your right you pass the Pasaje Ripalda, a shopping gallery with a glass roof. Take the alley on your left before you reach Plaza de la Reina and you will step into the charming Plaza Redonda 2 [map] (‘Round Square’). This caprice of mid-19th-century urban development, inaccessible to cars, is known affectionately by the locals as el Clot (the Hole). Arranged around the fountain in the middle is a small ring of stalls specialising in haberdashery, ceramics and work clothes.

Plaza Redonda

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Via Augusta

Once Spain had been brought fully under Roman control, the Emperor Augustus (27BC–AD14) ordered a road to be built down the east coast, linking the Pyrenees and Cádiz. Named the Via Augusta after the emperor, it extended 1,500km (930 miles) and was the longest Roman road in the Iberian Peninsula. Although it was primarily intended to enable troop movements, it also facilitated trade. Its route runs through Sagunt to Valencia where it passes through the Plaza de la Reina in the centre of the city.

You can easily get lost exploring the maze of streets beyond the Plaza Redonda, but for now it is best to retrace your steps up the alley and continue into the Plaza de la Reina (formerly known as Plaza Zaragoza). As a taster before visiting the cathedral, which lies ahead of you, it is worth visiting the Iglesia de Santa Catalina 3 [map], impossible to miss because of its distinctive baroque belltower built on a hexagonal plan. The church proper inside is not baroque at all, but a pure and soothing Gothic. Near the entrance to the church, is one of Valencia’s oldest horchaterías (for more information, click here): Santa Catalina (www.horchateriasantacatalina.com), with tiled decorations and marble tables.

The cathedral

The top side of the Plaza de la Virgen is formed by Valencia’s magnificent Catedral 4 [map] (winter: Mon–Sat 10am–5.30pm, Sun 2–5.30pm; summer Mon–Sat 10am–6.30pm, Sun 2–6.30pm; charge; www.catedraldevalencia.es), with its octagonal belltower, El Miguelete, rising above it. The foundation stone for the building was laid in 1262 on the site of a mosque, and although it was begun in the prevailing Romanesque style the majority of it is Gothic. You wouldn’t think so, however, as you approach it up the square because the doorway before you, the Puerta de Hierros, is unrestrained baroque, the work of Konrad Rudolf, a German pupil of Bernini. Although this is the main façade, it looks cramped and uncomfortable because it had to be superimposed on a pre-existing building, with the immovable El Miguelete taking up much of the space.

To appreciate the simplicity of the cathedral it is best to skirt round it to the right and enter by the earliest doorway, the rounded Romanesque Puerta del Palau, which gives on to the Plaza del Palacio del Arzobispal. This has a pleasingly understated decoration. The 14 small heads under the cornice are said to represent seven men and their wives who came from Lerida to repopulate Valencia after the Christians had reconquered it from the Moors.

The cathedral’s Gothic nave

iStock

Once inside the cathedral you can fully appreciate its basic Gothic structure. The nave is now of clean stone – most of the extraneous 18th-century decoration having been removed in the 1980s.

It is lit by an elegant cimborrio, an ocatagonal, two-storey lantern which is pierced by windows of delicate tracery, the sunlight filtered through panes of alabaster.

The altar, however, is an elaborate accumulation of Renaissance and baroque art, the altarpiece being by two artists heavily influenced by Leonardo da Vinci. One grisly point of interest behind the altar is the brown and shrivelled mummified forearm of St Vincent the Deacon, co-patron of the city, who was martyred in Valencia in 304.

Valencia’s Holy Grail

Like Turin’s shroud, the purported Holy Grail in Valencia’s cathedral has been the subject of a great deal of speculation. In 1960, a professor of archaeology at Zaragoza University dismantled and examined the cup and proclaimed it to be of a date prior to Jesus Christ and made in a workshop of the Near East; but there is no evidence connecting it directly to New Testament events.

According to legend it was taken from Jerusalem to Rome by Saint Peter and there used by popes to celebrate mass. When the Emperor Valerian persecuted the Church and tried to confiscate its treasures, San Lorenzo – the first deacon of the Church – dispatched the grail to Huesca, in the Pyrenean foothills, for safety, three days before being martyred for his faith. It now made its appearance in historical documents. During the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, the grail was kept in the remote monastery of San Juan de la Peña.

In 1437 it arrived in Valencia where it has been ever since, except during the Napoleonic occupation of Spain when it was smuggled out for safe-keeping.

Altogether more beguiling is the cathedral’s most famous relic, what is claimed to be the Holy Grail, the cup that Jesus Christ drank out of at the Last Supper. The small, dark red agate cup, which in the 14th century was set in a gold framework studded with jewels, is on display in a gloomy chapel, formerly a chapterhouse, beneath a roof of stellar vaulting sprouting from coloured bosses.

The Chapel of the Holy Grail gives access to the cathedral museum (https://museocatedralvalencia.com) which houses a few treasures, including some of the original polychrome statues, two paintings by Goya, other paintings by Juan de Juanes and a giant monstrance which is taken through the streets of Valencia during the procession of Corpus Christi.

The Miguelete

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The last thing to do before leaving the cathedral is to climb the octagonal belltower of the Miguelete (Micalet in Valencian; summer daily 10am–7.30pm, winter Mon–Sat 10am–6.30pm, Sun 10am–1pm and 5.30–7pm; extra charge), which demands the giddying ascent of a spiral staircase of more than 200 steps to a terrace over 50m (160ft) above the city streets below. The tower owes its name to having been consecrated on 29 September 1418, the feast day of the archangel St Michael, Miguelete being the affectionately diminutive form of his name.

From the tower, peels rang across the city in the late Middle Ages announcing the times to open and close the city gates. The bellcote crowning the tower today is, however, a later addition.

Outside the cathedral

Leave the cathedral by the door opposite the main entrance, the Puerta de los Apóstoles, a triumph of 14th-century Gothic sculpture attributed to Nicolás de Ancona. Looking behind you, you can admire the veritable crowd of Biblical characters gathered around the door, including 14 angels, 16 saints, 18 prophets and, to the sides of the door, the apostles standing on triangular pillars and sheltered by tabernacles. All these statues were originally coloured and kept repainted until at least 1522 when they began to be badly worn by the elements. The worst eroded were withdrawn in modern times and have been replaced with copies.

Every Thursday at 12 noon this doorway becomes the setting for what is perhaps the most extraordinary court of law anywhere in the world. It is here that the Water Court (Tribunal de las Aguas) meets in public and in the open air to decide disputes between farmers over the use of irrigation water in the huerta around the city. The eight judges dressed in black smocks – all farmers themselves, elected by their peers – represent the different networks of water channels. Hearings are instant and oral (in Valencian): no records are taken; no appeal is possible: and no business is put off until another session. The court has met in this way weekly, with scarcely a break since 1239. When there is no debate the affair can be over while the clock is still striking midday – so get there promptly if you want to see it.

Plaza de la Virgen

The Puerta de los Apóstoles lets you out into the Plaza de la Virgen (built on top of the Roman forum), which is now a car-free place to mill around, feed pigeons, or sit in a pavement café and watch life go by. In the middle of the square is a fountain representing the god Triton, personifying the River Turia, surrounded by eight figures with pitchers pouring water, representing the principal irrigation channels feeding the huerta.

The fountain on Plaza de la Virgen

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The cathedral shares this square with two other impressive buildings. Beside the Puerta de los Apóstoles is what looks almost like a lost section of the Colosseum. This is an arcaded gallery belonging to the cathedral known as Els Balconets de la Seu, which serves as a dais from which church dignitaries can watch processions and other events taking place in the square. The most spectacular of these events is La Ofrenda, part of the Fallas festival in March, when a huge copy of the statue of Valencia’s patroness, the Virgen de los Desamparados (the Virgin of the Forsaken or Helpless), is made out of bunches of flowers brought by a lengthy procession of people dressed in traditional costume.

‘Little Hunchback’

The statue of Valencia’s patroness Virgin is nicknamed the Geperudeta, the ‘Little Hunchback’, because of a curve in its back. The story goes that the statue assumed this form through use in the funeral rites of outcasts such as executed criminals. The sculpture would be laid on the corpse, her head resting on a cushion, a position that caused her ‘curvature of the spine’.

The actual statue of the Virgin is of a more modest size and form, although obscured by the wig, rich clothes and jewels that lavishly adorn her.

The statue is kept on display above the altar in the church dedicated to her, the 17th-century Basílica de la Virgen de los Desamparados (daily 7am–2pm and 4.30–9pm; free). The first entirely baroque building to be erected in Valencia, it is connected to the cathedral’s dais by a high, enclosed bridge of Renaissance style used by members of the clergy only. The statue is poised on a swivel mechanism so that it can be brought to face the nave of the church or a small chapel intended for more intimate communion with the faithful. During Las Fallas she is honoured by a large display of flowers in the square outside the church.

Behind the church, through the arch formed by the bridge to the cathedral, is the Plaza Almoyna, site of the original Roman settlement of Valentia, off which are two lesser sights: an art gallery, the Museo de la Ciudad (Mon–Sat 10am–7pm, Sun 10am–2pm; free on Sun) housed in the former Palacio del Marqués de Campo, and El Almudín, a 13th–14th-century granary which once supplied the city with wheat and is now used to house exhibitions. Down an adjacent street, Calle del Almirante, is the only piece of Moorish architecture still standing in the city, the Baños del Almirante (Admiral’s Baths; Tue–Fri 10am–6pm, Sat–Sun 9am–2pm; guided visits every half hour; free on Sun).

The other conspicuous building on the Plaza de la Virgen, set back from it slightly, is the seat of the Valencian regional government, the Palau de la Generalitat 5 [map]. It looks old enough to be a fusion of Renaissance and Gothic, but only one tower is authentic – the other is a copy added in 1952.

Another important institution is housed in an old palace on the pedestranised Calle Navellos, which leads north from the Plaza de la Virgen towards the Torres de Serranos and the river. This is the Cortes Valencianas (Mon and Fri at 10, 11am, noon, and 1pm by appointment only, tel: 96 387 61 00; for details check www.cortsvalencianes.es; free), the regional parliament of the Comunidad Valenciana. It occupies the much-extended Palacio de Benicarló, which became the home of the Republican government in the Civil War after its exile from Madrid until the final victory of Franco’s forces.

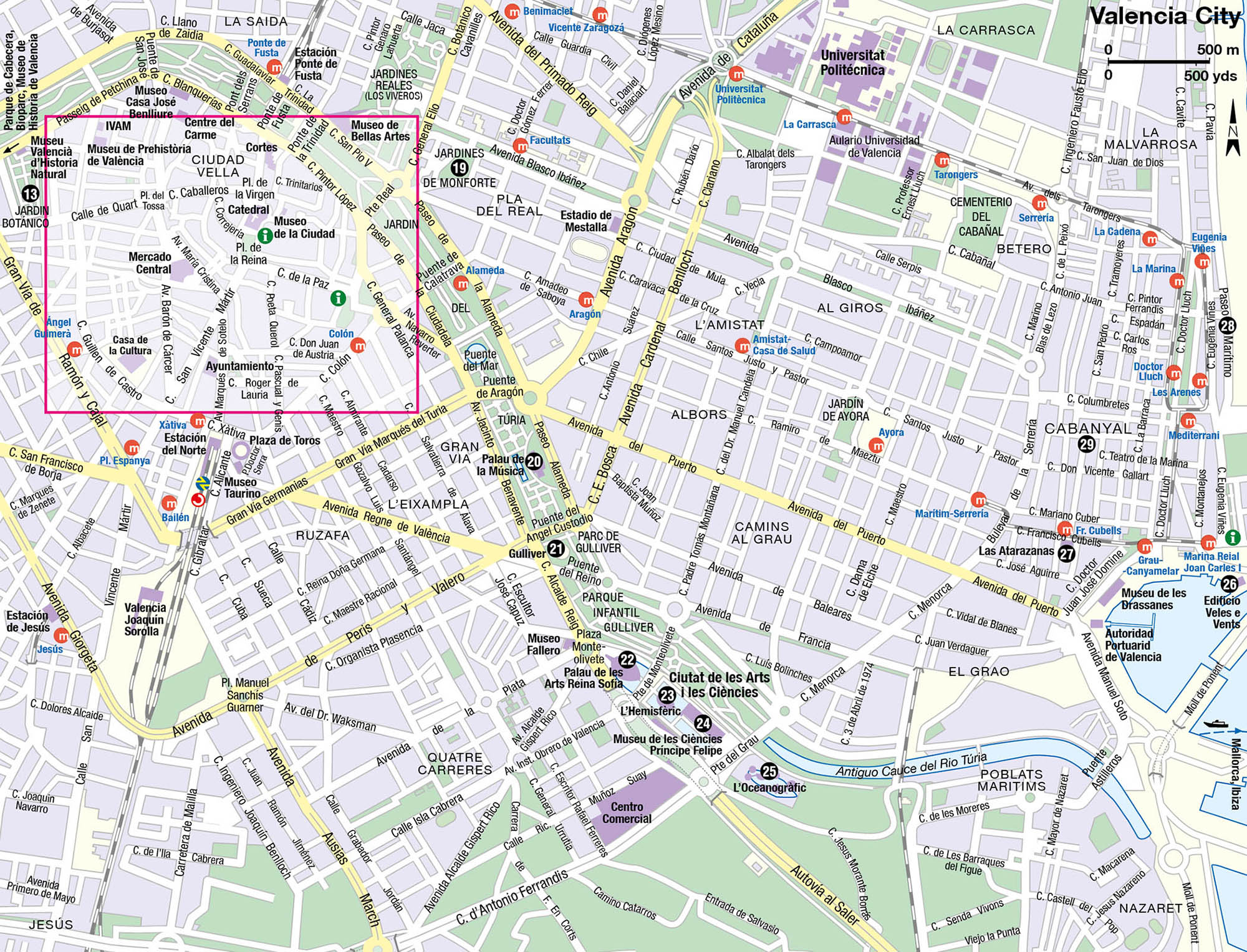

Barrio del Carmen, a favourite nightlife haunt

Getty Images

Barrio del Carmen

Take the street that runs beside the Palau de la Generalitat and you are on Calle Caballeros, the principal axis of Valencia’s oldest and most atmospheric quarter, the Barrio del Carmen 6 [map], an organic network of narrow, erratically twisting streets and alleys which suddenly open out into unsuspected little squares, where you can sometimes hear the silence despite being in the heart of a modern city. For decades during the 20th century, this area was left to crumble into squalid, undesirable tenement housing; chunks of plaster were regularly dislodged from its discoloured walls by the ricochets of fireworks during the Fallas fiestas. Finally, however, the city council decided to rehabilitate it, allowing the area’s unique character and the buildings’ surviving architectural details to be enjoyed. At night it is transformed into one of Valencia’s favourite nightlife haunts.

For a taste of the Barrio del Carmen you can just walk along Calle Caballeros, although this is not one of its typical streets because of the wealth of its residents. It is lined with mansions of more or less Gothic pedigree, mostly built around inner patios – which are often concealed behind street doors large enough to admit carriages when opened but forbidding enough to keep the riff-raff out when shut.

A better policy is to venture off this main street northwards. A right turn down Calle Salinas brings you to a curious example of how architecture can be adapted to new uses. A semicircular arch, the Portal de Valldigna, was once part of the 2-m (6.5-ft) thick wall built by Valencia’s Muslim rulers and later used as a point of access to the medieval Christian city. In the 17th century, two houses on either side of the street were joined together over the top of the gate.

Imposing Torres de Quart

iStock

If you continue wandering in the same direction, you will come to the rectangular Plaza del Carmen, one of the oldest squares in the city, overlooked by the Iglesia del Carmen, founded in the 13th century and much altered since. It has a baroque façade on three levels and an angel as a weathervane. The church once formed part of a Carmelite convent, which now contains the Centro del Carmen; Tue–Sun 11am–7pm; free), a cultural centre and museum displaying late-19th century to early-20th century Valencian art.

At the end of Calle Caballeros is the Plaza del Tossal. Here a section of the Moorish-era wall, together with a watchtower, can be seen in the Galería del Tossal (Tue–Sat 4–7pm, Sun 10am–2pm; charge). It is believed to be part of the al-Hanax gate, one of the city’s five entrance points in the wall built between 1021 and 1061 when Valencia was capital of a Muslim kingdom.

A short walk beyond the Plaza del Tossal, down Calle de Quart, brings you to the edge of the Barrio del Carmen, marked by the Torres de Quart 7 [map], one of the old city gates. This was built between 1441 and 1460, using Naples’ Castel Nuovo as a model. When the walls fell into disuse, the gate was turned into a women’s prison. The holes that can be seen in the outside walls are said to have been made by projectiles fired by the French during their siege of Valencia in 1808 and left unrepaired as a memorial to the resilience of the citizens.

The market and La Lonja

South of the Barrio del Carmen, down Calle Bolsería from Plaza del Tossal, you come to three very different buildings sharing the triangular Plaza del Mercado, where those deemed heretics by the Inquisition were burned at the stake.

Vane attempt

The spire of the Iglesia de los Santos Juanes used to be crowned by a weather-vane of a bird which, according to tradition, was used as a distraction by poor parents who wanted to abandon their children: they would point to the bird and, when the child was looking up, slip away into the crowd.

Church of the Sts John

The Iglesia de los Santos Juanes 8 [map] began life as a Gothic structure, built on the site of a mosque. It was badly damaged by fires in the 16th century and had to be almost totally rebuilt during the 17th and 18th centuries. Only the nave and a large blank disc at the west end, which was to have been a rose window, suggest the church’s Gothic origins; otherwise it is a somewhat disappointing baroque. Still, the frescoes of the Apocalypse on the vaults by Antonio Palomino are worth seeing as are the statues of the Twelve Tribes of Israel, sculpted by Jacobo Bertessi.

The main façade, forming an odd juxtaposition with the other two buildings on the square, is unusual for having a terrace jutting out from its base which was used as a platform from which dignitaries could watch public spectacles. Below it are basement chambers with doors onto the street known as les covetes de Sant Joan (St John’s caves). At the top of the façade is a clocktower with figures of the two St Johns to whom the church is dedicated.

Mercado Central

Adjacent to the church is the antidote to a morning spent sightseeing too many historical monuments: the Mercado Central 9 [map] (www.mercadocentralvalencia.es; Mon–Sat 7am–3pm). The principal market of the city, indeed one of the biggest markets in Europe, is housed in a handsome art-nouveau building with wrought-iron vaults and a central dome. Designed for the everyday business of buying and selling, it nevertheless has delightful ornamental touches in ceramic, brick and stained glass – most notably the red and yellow stripes of Valencia’s flag, the senyera. When it was inaugurated in 1928 by King Alfonso XIII the market had well over 1,000 stalls. Consolidation among the traders has reduced this number to around 700, which still gives the shopper plenty of choice. The best time to get here is mid-morning when it bustles with people calling out their orders in Valencian and stuffing shopping baskets and trolleys with fruits and vegetables. If you are not going out into the huerta, where oranges are sold by growers by the roadsides, buy them here. Some stalls also sell herbs and spices, others dried fruit and nuts, and one specialises in ostrich eggs and meat. A separate part of the market is for fish and seafood.

Mercado Central

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Outside, if you are peckish, you can get some freshly fried churros – like long, thin doughnuts – a popular sweet snack, or a takeaway portion of paella. A stall near the entrance sells paella pans in a range of sizes with gas rings to match, together with the necessary cooking implements.

La Lonja

Across the road from the market is Valencia’s favourite building, a true temple to commerce. La Lonja ) [map] (Mon–Sat 10am–7pm, Sun 10am–2pm; charge), originally used for trading in silk and later as a general commodities exchange, is one of Europe’s finest examples of civil Gothic architecture. It was modelled on a similar building in Palma de Mallorca and built between 1483 and 1498.

The exterior is lavishly decorated in carved stone with tracery, filigree, ajimez windows (divided into two lights by slender columns) and spiky crenellations beneath which gargoyles leap out. If you look closely at street level you can get a glimpse of the more playful side of the craftsmen responsible: among the figures incorporated in the stonework is one showing his naked buttocks to the observer.

Interior of La Lonja, the 15th-century silk merchants’ market

iStock

The building is divided into three parts by a central tower, which contains a chapel and a prison once used for merchants who defaulted on their debts. The part to the left of the tower was occupied by two institutions: the Consulado del Mar, the regulatory body that oversaw maritime trade, and the Taula de Canvis, the city’s first banking body, which was largely responsible for financing the construction of La Lonja.

Entering to the right of the tower, you step immediately into the building’s most graceful space, the Transactions Hall, which is divided into three naves. The high ceiling is held aloft by eight gracefully spiralling columns which sprout at the top into stellar vaulting. An inscription running round the chamber reads, ‘I am a famous house which took fifteen years to build. See how fine a thing commerce can be when its words are not deceitful, when it keeps its oaths and does not practise usury. The merchant who lives in such a way will have riches and enjoy eternal life.’

Behind La Lonja is a warren of narrow streets and squares dotted with small shops. With luck you should emerge underneath the tower of the Iglesia de Santa Catalina, at the corner of the Plaza de la Virgen, ready to visit a very different part of the city centre.

Museo de Cerámica

From the bottom of Plaza de la Reina, a straight street, Calle de la Paz, leads towards the modern shopping zone of the city centre. Take the second turning on the left, Calle Marqués de Dos Aguas, to get to Spain’s national ceramics museum, the Museo Nacional de Cerámica González Martí ! [map] (http://mnceramica.mcu.es; Tue–Sat 10am–2pm and 4–8pm; Sun 10am–2pm; charge). This is contained within an extraordinary building, the Churrigueresque (an extreme Spanish form of baroque) mansion of the Marquis of Dos Aguas: an 18th-century extravaganza of coloured plaster. The doorway is particularly striking. It is a dripping fantasy in alabaster designed by Hipólito Rovira and executed by the sculptor Ignacio Vergara. Ostensibly it is a portrait of the Virgen del Rosario but below it becomes a pun on the marquis’ surname, Two Waters. On either side of the door two semi-nude male figures recline, while below them water representing the two rivers of Valencia, the Turia and Júcar, flows from twin pitchers. Around the figures runs a voluptuous mass of vegetation.

The Museo Nacional de Cerámica González Martí

iStock

Beyond the portal, the museum doesn’t disappoint. It is an eclectic delight of all things old and dazzling – even if you can’t warm to pottery and porcelain, you are likely to find something to fascinate you. To begin with there are the rooms of the mansion itself, with their spiralling gold columns hung with grapes, cherubs and pink plaster cornices. They form the backdrop to everything on display. The most striking single exhibit, perhaps, is the marquis’ Cinderella-style formal Carriage of the Nymphs, another Rovira/Vergara over-indulgence in excessive ornamentation. Other things to be seen include canopied beds and various items of furniture, a collection of Ex-Libris bookplates, old posters, photographs, books, sketches, engravings, caricatures, jewellery, silver and ephemera galore to do with celebrated Valencians.

Colegio del Patriarca

123RF

The ceramics museum proper has some 5,000 pieces beginning with prehistoric, Greek and Roman specimens, passing through Oriental pieces, and ending with creations by Picasso. The core of it was amassed by Manuel González Marti, discoverer of potteries that flourished in the Middle Ages near Valencia. The outstanding treasures of the museum are medieval pieces made in ceramic-making towns near Valencia – Paterna, Manises and at the Royal Factory in Alcora – which are executed in greens, blacks and blues, often with metallic sheens. Among the more unusual pieces are 15th- and 16th-century examples of a technique associated with Paterna known as socarrat (between toasted and burnt). These tiles, which were designed to be placed between the beams on the ceiling, depict animals, flowers, ships, geometric patterns in spontaneous lines and rough shapes of red or black. The most popular exhibit in the museum is a complete traditional 19th-century Valencian kitchen richly decked out in ceramic tiles with panels depicting food and animals.

To see a more mundane use of ceramic decoration, continue down the street (it becomes Poeta Querol after the museum) until you come to the corner formed by the Teatro Principal. Look up left at the upper storeys of the neo-baroque 1935 triangular building of the Banco de Valencia building which forms a rounded corner between two streets. Above the penultimate balcony are two floors adorned with brightly coloured tilework against a contrasting red background.

The university and El Patriarca

The streets opposite the ceramics museum lead to two venerable Valencian institutions, the university and El Patriarca. The neo-classical university was begun in the 15th century, although it is largely the result of later work.

The philosopher

In the patio of the university stands a statue of Valencian-born Juan Luis Vives (1492–1540), also known as Ludovicus. This brilliant philosopher and humanist spent most of his life outside Spain because of persecution due to his Jewish roots. In England he tutored Princess Mary (later Mary I) and took up a post at Oxford, where he formed close friendships with Thomas More and Erasmus.

Next to the university is the Real Colegio de Corpus Cristi, commonly known as the Colegio del Patriarca @ [map] (guided tours in English Mon–Fri at 11am and 5pm, Sat 11am; booking essential; http://patriarcavalencia.es; charge) in honour of its founder, the 16th-century archbishop and viceroy of Valencia, and Patriarch of Antioch, St John de Ribera (1532–1611). Ribera was a leading spirit of the Counter-Reformation, the repressive principles of which he applied in the seminary he founded. The focal point of the complex is a two-storey Renaissance patio composed of a double gallery of arches supported by 56 marble columns shipped in from Genoa. The statue in the middle of the courtyard depicts the archbishop himself, sculpted by local artist Mariano Benlliure.

To one side of the patio is a church whose walls and ceilings are entirely covered with richly coloured frescoes by Bartolomé Matarana. The 9.30am service (Tue–Sun and Thu 7.30pm) is in Gregorian chant. Above the altar you will normally see a beautiful version of the Last Supper by Francisco Ribalta, but during Friday morning mass (at 10.25) this is theatrically lowered to reveal a painting of the crucifixion by an anonymous 15th-century German artist hidden beneath.

There are various works of art scattered around the Patriarca, including some fine Brussels tapestries. But several rooms are specifically dedicated to displaying an important collection of paintings by Spanish and foreign masters, including El Greco, Juan de Juanes, Caravaggio, Sariñena, Ribalta, Van der Weyden and Morales.

Along the River Turia

It’s not every city that can turn its river into a pedestrian urban freeway, but that is what Valencia has effectively done. After serious floods in 1957, the Turia was diverted through the outskirts to the south leaving its dry bed still flowing through the urban area in a large and strategic arc west to east. The bold decision was then taken to make the former course of the river into a ribbon of green for recreational use and the celebration of the arts, and it now serves as an elongated sports and cultural resource available to all, its amenities joined up by pedestrian and cycle routes.

Tranquil garden along the riverbed

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

For over 6km (4 miles), from the Puente Nou d’Octubre to the Puente de Astilleros, the riverbed is a procession of gardens, sports fields and playgrounds, all planted with a variety of trees, either native to the region or adapted to the climate, notable among them pines, palms, carobs and olives. Between these two crossing points are a further 17 bridges, seven of them expressly built as part of the riverbed rehabilitation project. If you want to walk the whole length of the river, begin at Nou d’Octubre station on metro line 3 in the suburb of Mislata (there are several buses that go there too).

The upper Turia

This river of gardens begins upstream in the west with the Parque de Cabecera (or Capçalera). Next to the park is the extraordinary Bioparc, an extensive zoo which recreates different African habitats.

The park is divided into several ecosystems: savannah, equatorial African forest, African wetlands and that of Madagascar. The African savannah includes an acacia forest and is inhabited by zebras, impalas, giraffes and rhinoceros. Big rocky formations recreate a typical African landscape, and lions rest on top of rocks overlooking the zebras and antelopes. There is also a palm forest inspired by those found in Kenya, and a stand of baobabs where a herd of African elephants can be seen drinking at the lake (opening hours vary, for details see www.bioparcvalencia.es; charge).

Next to this, on Calle Valencia, a continuation of the Passeig de Petchina (which runs along the southern riverbank), is the Museo de Historia de Valencia (Tue–Sat 10am–7pm, Sun 10am–2pm; www.museosymonumentosvalencia.com; charge), housed in a 19th-century water cistern. The exhibits tell the story of the city from its foundation by the Romans to the present day. Every section is equipped with a ‘time machine’, consisting of a life-size screen on which actors portray scenes from history in the language of your choice.

The elephants are a highlight of the Bioparc

Valencia Tourism

Follow the south bank of the river and on the other side of the Puente de Ademuz you’ll find the Museu Valencià d’Historia Natural £ [map] (Natural History Museum; Sat–Sun 10am–1pm; www.mvhn.es; free). Behind this is the Jardin Botánico (daily 10am–6pm; closes 1–2 hours later in spring/summer; charge), a university botanic garden created on the present site – which was then outside the city walls – in 1802. It is planted with 4,500 species organised into 20 collections, including plants useful to humans, a tropical greenhouse, water plants, carnivorous plants, native Valencian species, woodlands and palms. Its most original feature is the Umbraculo, a pergola built of brick and iron.

A little further down the southern river bank, on the corner of Calle Guillem de Castro, is the Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno $ [map] (IVAM; www.ivam.es; Tue–Sun 11am–7.30pm, Fri until 9pm; guided visits by appointment; free on Sun and Fri from 7.30pm), which is considered one of the top modern art galleries in Spain. The collection concentrates on Julio González, acclaimed as the father of 20th-century Spanish sculpture. Its eight galleries include one in which remains of the medieval city wall can be seen.

If you prefer art at the opposite end of the chronological spectrum, have a look at the prehistory museum next to the IVAM, the Museu de Prehistòria de València % [map] (Tue–Sun 10am–8pm; charge), in which you can see undeciphered engravings made by prehistoric people living in the hills of Valencia.

Round the bend in the river, just after Puente de San José, is a museum of art of a different kind, the Casa Museo de José Benlliure (Tue–Sat 10am–2pm and 3pm–7pm; Sun 10am–2pm; free on Sun). This is the former home of the prominent Valencian painter José Benlliure who died in 1937. There is a pretty garden with Valencian ceramics to wander round.

Torres de Serranos

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The next monument you come to, still on the same bank of the river, is the Torres de Serranos ^ [map] (Mon–Sat 10am–7pm, Sun 10am–2pm; charge). One of the few remaining bits of Valencia’s medieval city walls – and more glamorous than the Torres de Quart – this gateway was built in the 14th century using one of the doors of Poblet monastery in Catalonia as a model and combines defensive and decorative features. Its two towers are topped by battlements as if ready for war, but the central panel over the gateway is embellished with delicate Gothic tracery, giving a clue that this is more triumphal arch than defensive installation. Its structure was left exposed at the back to prevent the towers being used against the citizenry. From the Plaza de los Fueros behind you can see its various chambers – which have cross-ribbed vaults – once used as a jail for miscreant nobles. Four gargoyles protrude from this rear wall.

Across the next bridge, the Pont de Fusta, is a railway station, once used for a quaint system of narrow-gauge railways but now serving the high-tech tram which departs for the beach. Down this next stretch of the northern bank of the river are two monumental buildings and two gardens. At the end of Puente de la Trinidad is the Real Monasterio de la Santísima Trinidad (guided visits only; book at http://monasteriotrinidad.es), a working convent inhabited by a closed order of nuns. The monastery door is pure Flamboyant Gothic.

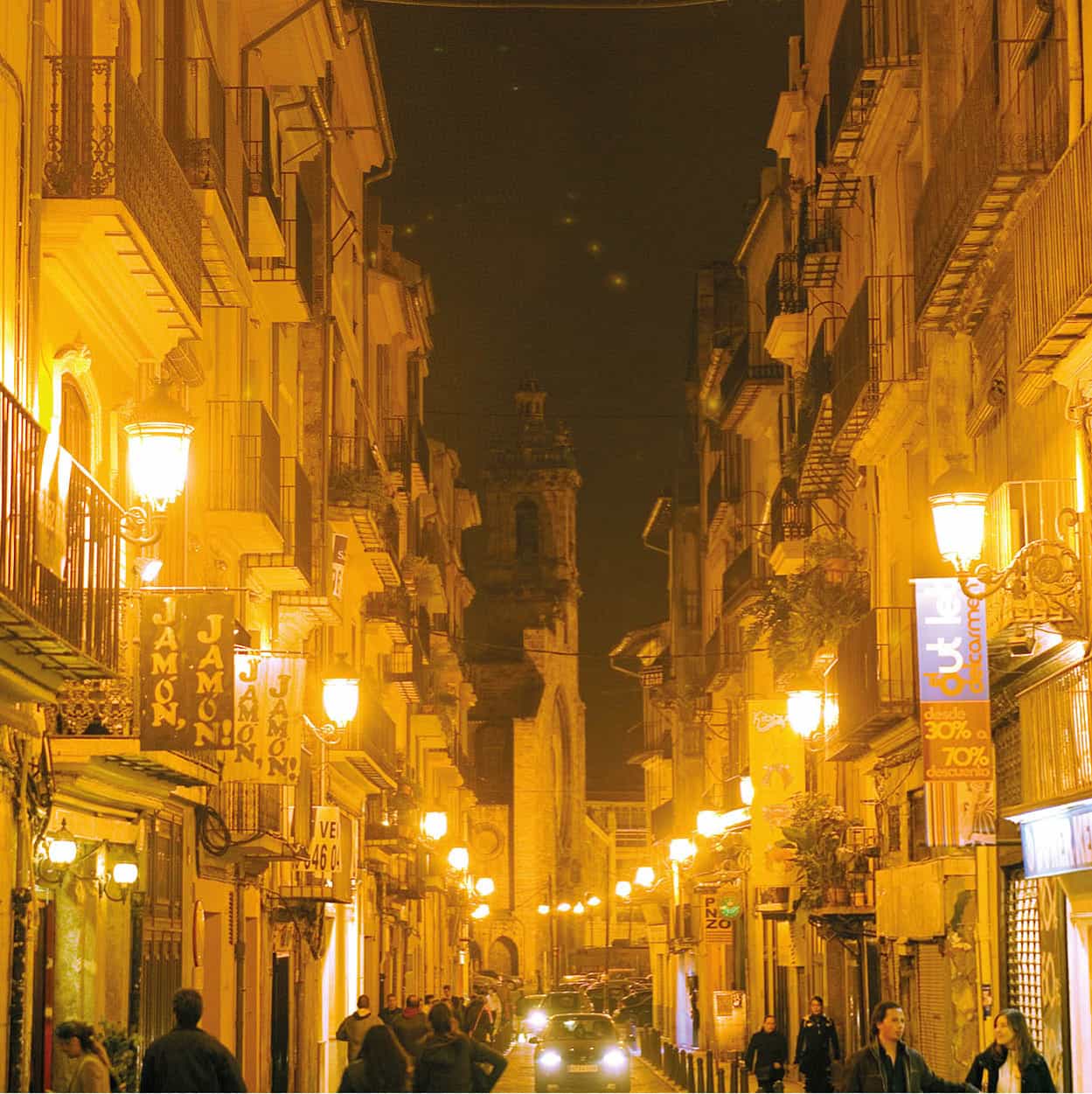

Valencian artists

One part of the Fine Arts Museum of particular interest presents the work of three little-known Valencian artists of the 19th and 20th centuries who were inspired by the sea, the colours of the huerta and the light cast by the Mediterranean sunshine: Ignacio Pinazo, Antonio Muñoz Degrain and, above all, the Impressionist Joaquín Sorolla.

Museo de Bellas Artes

Next to this is the Museo de Bellas Artes & [map] (Museum of Fine Arts; Tue–Sun 10am–8pm; www.museobellasartesvalencia.gva.es; free) housed in a 17th-century seminary. This might not compete in size with the large galleries of Madrid and Barcelona but it has an important collection nonetheless, focusing on painting of the Gothic period. You enter via an octagonal vestibule covered by a blue cupola and ascend two floors of galleries. Upstairs, the most outstanding pieces are ‘primitive’ Valencian painting of the 14th and 15th centuries, represented by a series of huge golden altarpieces painted in tempera and later, under Flemish influence, in oils by artists such as Jacomart, Miguel Alcanyis, Maestro de Bonastre and Pere Nicolau. Other outstanding works include Hieronymus Bosch’s Triptych of the Passion, showing the tormenting of Christ, and Velázquez’s self-portrait. There are also works by El Greco, Van Dyck, Murillo, Ribalta and the local Renaissance painter, Juan de Juanes. There are six paintings by Goya here, although none of them is exceptional.

Museo de Bellas Artes poster

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Elio’s mountains

Los Viveros occupies the site of a Moorish country house, later Christian palace and royal residence which was demolished during the Peninsular War. When the war was over, rubble from the palace was swept together to form two artificial hills, Las Montañitas de Elio, named after the general who ordered their building.

Los Viveros and beyond

The Museo de Bellas Artes stands at the corner of the city’s largest garden, the Jardines del Real, better known locally as Los Viveros * [map] (The Nurseries; daily 8am–sunset; free). The garden has a wide variety of different spaces within it connected by broad paseos. There are fountains, pergolas, a restaurant often used for weddings, lawns, ornately decorated benches, bronze and marble sculptures galore and a lake with ducks. Here and there are intriguing bits of historic architecture salvaged from demolition sites: a baroque doorway, a pink and grey marble fountain from a monastery, and sample houses from the Valencian huerta. The garden is the venue of popular concerts in summer and also includes the Museo de Ciencias Naturales (Natural Sciences Museum; Tue–Sun 10am–7pm; charge).

Near Los Viveros, a few steps away from the riverbed, are more gardens, this time protected from the rush and noise of the city by a wall. The Jardines de Monforte ( [map] were created in the 19th century by Juan Bautista Romero, a wealthy Valencian landowner, and designed by the architect of the bullring. They are Italian in inspiration and neo-classical in style, with hedges closely trimmed into geometric forms, a long shady arbour, trickling fountains and a scattering of sculptures and marble statues, creating many intimate spaces.

From the corner of Los Viveros, the next kilometre of the left or north bank of the river becomes the Paseo de la Alameda, a broad avenue. Diagonally across the river from Los Viveros are two churches which would be worth seeing but are hard to visit: the Iglesia del Temple, which, as its name suggests, owes its origins to the Knights Templar, and the Iglesia de Santo Domingo (group visits only by appointment 8am–2pm; tel: 96 196 30 38), which has a beautiful Gothic cloister and 15th-century chapel but is now owned by the military.

Four bridges stand close to each other here, beginning with the stark white Puente de Calatrava. Built of extra-tensile steel and with a span of 131m (430ft) supported by a single arch set at 70 degrees from the horizontal, it was designed by the Valencian architect Santiago Calatrava, who is also responsible for the adjacent metro station (and most of the Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciènces).

‘La Peineta’

The sleek, white Puente de Calatrava has been given the nickname of ‘La Peineta’ for its resemblance to the ornamental combs worn by women as part of the traditional Valencian costume.

On the city side of the river is the Plaza Porta del Mar, marking the site of the gate in the city wall that communicated with the harbour. This was the last gate to be closed at night and anyone absent-mindedly arriving late was forced to sleep in the open air across the river, giving rise to the expression ‘to be left out under the moon of Valencia’, meaning to be left in the lurch. These days the term Luna de Valencia (Moon of Valencia) has been expropriated to refer to the city’s nightlife.

A short way further down the river is the 10-arched Puente del Mar, built in 1591 and one of the oldest bridges still standing. Each end is marked by broad flights of steps and the bridge itself is adorned with canopied sculptures of the Virgin Mary and St Paschal.

Palau de la Música

iStock

Continuing down the riverbed parklands, the next sight you come to, beyond the Puente de Aragón, is the Palau de la Música , [map], an ultra-modern concert hall which could almost be a greenhouse for the amount of glass incorporated into its remarkable construction. The main auditorium has such excellent acoustics that the Spanish tenor Plácido Domingo is said to have remarked after his first concert here that ‘El Palau is a Stradivarius’. As well as ballet, opera, classical and jazz concerts, the Palau also hosts modern art exhibitions.

The final stretch

Over the other side of the next bridge, Puente del Angel Custodio, a giant sculpture of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver⁄ [map] lies prostrate in the riverbed acting as a great climbing frame and slide for children.

The last bridge before reaching the riverbed’s end at the Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciènces is the city’s longest. The Puente del Reino marches obliquely across the river taking a nonchalant 220m (720ft) to get from one bank to the other and is lit by art-deco lampposts. Raised on plinths at either end are the guardians of the bridge: four snarling pseudo-Gothic gargoyles in bronze, human of body but with the heads of beasts and half-unfurled wings, designed by the engineer who built the bridge, Salvadór Monleón.

There is one more sight of interest on the south bank of the river, and that is the Museo Fallero on the corner of Plaza Monteolivete (Tue–Sat 10am–7pm, Sun until 2pm, free on Sun). The museum honours the tradition of the Fallas, the fireworks festivals held each year in March (for more information, click here), and houses ninots, comic figures in papier-mâché, which have been saved by popular acclaim from the usual conflagration.

Zorbing in front of the Hemisfèric

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Visiting the City of Arts and Sciences

Except for the Oceanogràfic, it is possible to walk around the City of Arts and Sciences (www.cac.es) at your leisure and enjoy much of the architecture for free. If you want to visit all parts of it inside and out, however, you’ll need to buy a combined ticket (€37.40 at the time of writing) giving admission to L’Hemisfèric, the Museu de Les Ciències Príncipe Felipe and L’Oceanogràfic. A ticket can be bought from any of the ticket offices or online. This is valid for one, two or three days (they don’t have to be consecutive) and permits you to visit each attraction once only.

The City of Arts and Sciences

As the bed of the River Turia nears the sea, the new developments along it reach a climax in the futuristic cultural complex of the Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències, the City of Arts and Sciences. This ambitious complex aims to encourage visitors to combine leisure with an exploration of the arts, sciences and nature. It consists of five stunning, futuristic buildings, four of them by Santiago Calatrava, standing in a 1.8-km (1-mile) alignment.

Palau de les Arts

Approaching from the city, the first of the buildings is a spectacular concert hall, the Palau de les Arts Reina Sofía ¤ [map], which has a 75-m- (250-ft-) high, domed roof clad in white mosaic tiles. This was the last part of the complex to be completed. The building houses four separate theatres with a combined capacity of over 4,000 seats, designed to provide Valencia with a world-class stage for high-quality opera, concerts, ballet and theatre.

L’Hemisfèric

The concert hall is separated from the other buildings by a bridge, the Puente de Monteolivete, on the other side of which is a hi-tech cinema, L’Hemisfèric ‹ [map], the first part of the city to open in 1998. This eye-shaped cinema has sides like folding portcullises which open and close in imitation of a blinking eyelid. Its singular aspect has been enhanced by placing it between two symmetrical shallow rectangular ponds. Under what turns out to be an elaborate oval canopy is a sphere stuffed with high technology where banks of comfortable seats look up at a gigantic, inclined, concave screen 24m (80ft) in diameter. The Hemisfèric’s main function is to project the moving images of IMAX films which exceed the limits of human binocular vision, sucking the viewer into the larger-than-life action. It is an overwhelming sensory experience which can be dizzying and disorientating. The cinema is also geared up for laser shows and as a planetarium in which more than 9,000 stars are visible.

Museu de les Ciències Príncipe Felipe

The next building is one of Spain’s largest science museums, the Museu de les Ciències Príncipe Felipe › [map] (Jul–Aug daily 10am–9pm, until 6pm in winter; charge), a sloping skeletal structure of steel and glass composed of vast intersecting white arches and taut buttresses. It looks like a cross between a cathedral, a space-age aircraft hangar, and the chalky skeleton of some fossilised sea creature.

The exhibitions are arranged on four floors, although you can walk about some parts of the building, notably Calle Mayor and the terrace, both one level up from the entrance, without paying the admission fee. The contents are fairly standard science museum exhibits, covering life, the Earth, science and technology with many interactive exhibits.

L’Umbracle

Opposite the science museum, across another shallow rectangular pond, is L’Umbracle (daily 8am–12.30am; charge). This is a cleverly disguised car park forming the south side of the complex and screening the rest of it from the road. The roof of the car park has been turned into a winter garden, covered by what looks like a giant white cloche – umbracle means arbour or pergola – 18m (60ft) high. If L’Umbracle is the least spectacular part of the city, it is also the most peaceful and a pleasant place to stroll around when you want to get away from the crowds. It is planted with various species of shrubs and trees native to Valencia and others selected for their adaptation to the climate. As the space has to make either an artistic or scientific contribution to the whole, there are several sculptures to admire in the shade, including EX IT by Yoko Ono.

L’Oceanogràfic, much more than an aquarium

iStock

L’Oceanogràfic

The final and largest part of the city is technically an aquarium but is, in reality, far more than that. L’Oceanogràfic fi [map] (closing times are variable so check ahead at www.oceanografic.org; daily 10am–6–8pm, until midnight in summer; charge) is made up of a series of lagoons containing water varying according to salinity, temperature and depth to represent the five oceans, and various pavilions or towers illustrating different marine environments – oceans, wetlands, tropical seas and the Arctic.

The last of these is an appealing igloo-like dome which is agreeably cool on a hot day outside. The whole place is connected by bridges, passageways and underwater glass tunnels – one being the longest such tunnel in the world.

Although it’s certainly an imaginative juxtaposition of original architecture and wildlife, it could be said that there isn’t enough of the latter to do justice to the former, even if the figures sound impressive: there are 10,000 individuals of 500 different marine species floating above, below or around you or, as is more usual in aquariums, sitting in dark corners of their tanks doing nothing. The whole place is conceived on three different levels and there are also a lot of ramps, stairs and lifts to negotiate as you go down into the depths to look at each habitat. Several events are staged during the day to add interest to a visit. The highlight of these is the dolphin and killer-whale show and it is worth making a note of the time of the next show when you arrive and getting to the dolphinarium early to save a seat.

Underwater dining

If you are truly in the aquatic mood, you may want to eat in one of L’Oceanogràfic’s underwater restaurants, Submarino, where you will be served a seafood meal surrounded by swimming fish. Be warned, though, it quickly gets booked up and you will need to reserve your table as far in advance as you can (tel: 96 197 55 65).

The seafront

Although much of Valencia’s historical prosperity derived from its role as Mediterranean port, until recently the city always kept its distance from – and its back to – the sea. The urban centre grew up just over 3km (2 miles) from the coast, far enough for the harbour area, El Grau, to be thought of as a distinct, unsavoury haunt of sailors, poor fishermen and lowlifes. Even today, the inhabitants of the maritime quarters – mostly proud people with strong local traditions – speak of ‘going to Valencia’. In the city centre, meanwhile, there is scarcely a hint of sea nearby except in the name of Avenida del Puerto, built at the start of the 20th century, leading discreetly off towards maritime perdition.

The beach, overlooked by the port’s cranes

iStock

The relationship only started to change in the 1960s when new suburbs filled the void between the two parts of the city. But then came tourism, which made city planners realise that their seashore was something to develop rather than ignore. The shabby port was spruced up, a new promenade (paseo marítimo) built for seaside recreation, and there were even controversial plans, eventually blocked by the Spanish Supreme Court, to continue Avenida Blasco Ibañez to the beach by bulldozing part of the historic Cabanyal fishing quarter. The final step in the rehabilitation of the seafront’s reputation was the awarding of the 2007 America’s Cup competition to Valencia (for more information, click here).

Now that the Avenida Blasco Ibañez extension isn’t going ahead, there are still only two ways to see the sea. The most direct way is by bus or taxi down Avenida del Puerto, a straight street running from the Plaza Zaragoza. A more interesting trip is by tram from the Pont de Fusta station, across the riverbed from the Torres de Serranos; take metro line 4 in the direction of Doctor Lluch and get off at Les Arenes.

The handsome Port Authority building

iStock

The port

In preparation for the America’s Cup, Valencia’s port has been split neatly in two. The south side concerns itself with the container and passenger terminals (catering for trippers to and from Mallorca and Ibiza), while the wharves on the north side, adjacent to the beach, have been transformed into a marina and leisure complex which is pleasant to stroll around. This is also where the European Formula 1 Grand Prix was held until 2012; the circuit is now sadly rundown. Some of the more attractive parts of the old port have been retained on the side nearest the Avenida del Mar, including the handsome Port Authority Building with its distinctive clock tower and some warehouses in a restrained mercantile brand of art nouveau.

The new developments centre on a striking modern structure, the Edificio Veles e Vents fl [map] (Sails and Winds Building), an iconic water pavilion designed by UK architect David Chipperfield.

Set back from the harbour, next to the church of Santa María del Mar, is Las Atarazanas ‡ [map] (Plaza Juan Antonio Benlliure; Tue–Sat 10am–2pm and 3–7pm, Sun 10am–2pm; charge), an ensemble of five Gothic sheds built at the end of the 16th century to serve as a workshop for boat building, an arsenal and a place to store maritime tackle. At the time of their building they stood at the head of the beach. This is now used as an exhibition space.

The Paseo de Neptuno and Paseo Marítimo

Stepping out of the side entrance of the port brings you onto Valencia’s flashy esplanade, the Paseo Marítimo ° [map], which begins with the pleasant Paseo de Neptuno. Along this little street are the front doors of a solid line of restaurants specialising in paella. Each has its back door opening onto the beach and almost all of them have glass-enclosed dining rooms and terraces. At weekends and in summer they can be very busy; at other times of the year you may well get the whole restaurant to yourself – but don’t take this as an indication that the food is not good. Prices along the restaurant strip vary and three establishments trade on ancient fame: La Pepica, L’Estimat and La Marcelina.

The Paseo de Neptuno ends abruptly at the luxury spa hotel of Las Arenas (or Les Arenes in Valencian), which retains two restored bright-blue classical temples (entirely rebuilt) that were once part of the old-fashioned restaurant complex that stood here.

From the corner of Las Arenas, the Paseo Marítimo becomes a 2-km (1.25-mile), palm-shaded multi-lane pedestrian motorway of dog walkers, pram pushers, joggers, ice-cream-licking toddlers and power-walking grannies. There is also a cycle track along the length of it. In summer the beach beside it can be packed with sunbathers, but off-season the fine golden sand provides a pitch for impromptu games of football or frisbee. The sea, except in exceptionally bad weather, has only a light swell, and is good for swimming: despite its proximity to a commercial port, most people consider it suitably clean.

Cabanyal architecture

Joanbanjo

For its last stretch, the Paseo Marítimo runs along Calle Isabel de Villena, where, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, affluent Valencians built themselves fine holiday villas. Among these worthies was the novelist and sometime republican-leaning politician Vicente Blasco Ibáñez (1867–1928) who found inspiration from the uninterrupted views of the sea. His reconstructed house is open to the public as the Casa-Museo Blasco Ibáñez (Tue–Sat 10am–2pm and 3–7pm, Sun 10am–4pm; free on Sun), containing portraits, photographs and sculptures of the writer, books and memorabilia.

The Cabanyal

A few streets back from the Paseo Marítimo is one of Valencia’s best-kept secrets, the old fishing quarter of the Cabanyal · [map]. This was once a defiantly self-contained community where everyone knew everyone and fishermen would sit on the pavements outside their houses mending their nets. You can still see signs of this spirit in a few surviving family-run corner shops and neighbourhood bars, the best of which is the Casa Montaña, which was founded in 1836 (for more information, click here).

Easter week

The Easter week procession through the Cabanyal puts the rest of Valencia to shame with its ostentatious legions of participants dressed as Biblical characters, Roman soldiers and, strangely, Napoleonic grenadiers.

There are no museums or monuments of note in the Cabanyal. Instead, the charm is in the ordinary architecture, at least those examples which have survived successive attempts at modernisation. The Cabanyal grew up as a patchwork of barracas, typical Valencian houses with steeply pitched thatch roofs, that were aligned in long streets parallel to the beach so that fishing nets could be laid out to dry. Gradually, around the turn of the 19th and into the 20th century the barracas were replaced by small, low family homes which were less vulnerable to fire. Many of these were decorated by their owners on the outside in eclectic, highly idiosyncratic styles broadly inspired by modernismo, the Spanish version of art nouveau.

Several of the houses have façades entirely clad in colourful ceramic tiles, which reflect heat and humidity and keep the interiors cool. Others, especially near the seafront, are tastefully painted in one or two pastel shades. Everywhere there are playful details to admire: intricate ironwork ornaments, stucco motifs, a Phaoronic head on the tiles of a balcony, a frieze hinting at Moorish Spain, tulips rampant up a door jamb, gargoyles and grotesque heads peering over the street. Look for them on any of the old streets: Reina, Barraca, Padre Luis Navarro, José Benlliure or Escalante.

Almost all the old houses in the Cabanyal are low level, of human proportions; many are back-to-backs and some are so small that they have only one room upstairs and one downstairs. The entire neighbourhood of Cabanyal is undergoing a thorough redevelopment with old houses being renovated, pavements widened and streets realigned. In 2017 alone more than €36 million has been allocated to upgrade the area.

Around the city

Valencia’s hinterland is easily explored by car or public transport from the city centre. You have a choice of fertile farmland, a watery nature reserve, historic ceramics-making centres or a medieval monastery.

The highly cultivated huerta

iStock

The huerta

If it is possible to visit Valencia without being reminded of the proximity of the sea, it isn’t easy to come away ignorant of the existence of an intensely fertile agricultural plain surrounding the city. Valencians have an almost spiritual attachment to this prime piece of farmland, the huerta. From its produce their city originally grew wealthy; later it was relied on to help them survive through hard times; and today the huerta continues to fill markets and provide the raw materials for Valencia’s traditional dishes and drinks.

Yet this natural resource is under threat from modernity. Theoretically, the huerta extends over a semicircle of land roughly bordered by the River Júcar to the south and the hills that start around Sagunt in the north. In practice, however, it is shrinking rapidly as it is encroached on by the growth of dormitory towns and the inexorable expansion of the outskirts of the metropolis.

But there is still huerta left and in places you can get an idea of how it must have looked in the days when agriculture was a leading industry here. At its most perfect, close to the city, the huerta is composed of smallholdings where not even the smallest patch of land is allowed to go to waste. The fine soil beneath the immaculate rows of artichokes, tomatoes, aubergines and flowers looks as if it has been sifted, fed and spoiled for generations, which it undoubtedly has. Given the warm climate, these plots can produce up to four crops a year if they are worked with care.

Such high productivity, of course, depends upon water. Crucial to farming the huerta are the acequias (irrigation channels) whose use and misuse is argued over weekly by the members of the Water Court (for more information, click here). On its arrival at Valencia, the River Turia is checked by an ingenious system of dams, sluices and overflows which feeds eight principal acequias in proportion to the amount of land they supply. These and other less noble acequias criss-cross the huerta, branching into ever smaller divisions to form a watery labyrinth of glistening channels. The original irrigation system was probably devised by the Romans, but it is the Moors who are credited with perfecting it; they came from Syria, Lebanon and Egypt where they knew all about the importance of irrigation to farming.

Oranges are Valencia’s major export crop

iStock

That the huerta has made fortunes for some enterprising farmers can be seen in the proud, exotic farmhouses, alquerias, that poke out from among the foliage. Some of them have towers and fanciful oriental touches; many have ceramic ornamentation gleaming in the sun. Much less common are barracas: traditional peasant houses with steeply pitched thatched roofs.

One corner of the huerta, Alboraya º [map] has built its fortune by specialising in a particular crop, the chufa or earth almond, Cyperus esculentus, a brilliant green, spiky, grass-like plant which is thought to have been introduced by the Moors. When the tubers of this plant are mashed with water and sugar they become horchata, a sweet milky drink which is served cold in summer (for more information, click here). The chufas of Valencia have their own denominación de origen, like wine grapes.

Another plant introduced to Spain by the Moors is the orange, which has since become Valencia’s most famous export crop.

When the trees flower in late February to early March the sweet smell of the blossom – azahar – fills the air and even pervades the built-up areas. String bags of ripe oranges hung on sale by the side of the road or next to a front door are a common sight in the first few months of the year. When buying oranges, don’t be put off by their often blotchy or scarred appearance. These unattractive fruit, rejected by wholesale export buyers, have plenty of juice and an intense flavour. The tastiest oranges, it is said, remain in Valencia.

La Albufera

To the south of the city, where there is even more water available, the huerta becomes a checkerboard of paddy fields which are sown and flooded in the spring for the rice to mature over the summer. In July and August the leaves of the crop reach full height and the whole area flushes a vivid emerald green. Over winter, after the autumn harvest, the landscape turns into a watery maze.

Barraca in La Albufera

Valencia Tourism

The rice fields converge on La Albufera ¡ [map], a freshwater lake beside the coast which is one of the Iberian Peninsula’s prime wetlands for birds and easily reached from Valencia by the motorway to El Saler. The lake is fed by the River Turia and connected to the sea by three channels or golas which are fitted with sluice gates to control the water level. It is extremely shallow, up to only 2.5m (8ft) deep, and is gradually shrinking because of natural silting and the reclamation of land by rice farmers. In the Middle Ages the lake was 10 times its present size.

If your main interest is primarily wildlife you may want to go first to Raco de l’Olla (by the turn-off to El Palmar), where there is an information centre (daily 9am–2pm; tel: 96 386 80 50; free) with a glass-domed observation tower for birdwatching. On the other hand if you are more interested in food, the village of El Palmar is the authentic place to eat paella and all i pebre (eels cooked with garlic and pepper). El Palmar is also the departure point for boat trips around parts of the lake.

If you are feeling adventurous you can try to negotiate the tracks that lead around the edges of the rice fields and along irrigation channels south from El Palmar to the low hill of La Muntanyeta de Sants and, eventually, the N332 main road.

Ploughing the rice fields

123RF

Birds of La Albufera

Well over 300 species of bird have been recorded in La Albufera, a figure which includes vagrants making a one-off appearance. With patience and binoculars you are usually sure to see herons (night, squacco and purple), egrets (cattle and little), ducks, waders, terns and gulls. Shy species like the bittern make good use of the lake’s reed beds and marshy islands, matas, to hide in. The bird population spills over into the neighbouring rice fields in search of food.

La Albufera is separated from the sea by a strip of sand dunes and Mediterranean woodland, 10km (6 miles) long and 1km (0.5 mile) wide, called the Dehesa which is fringed with sandy beaches, making it popular with tourists. When the beach-lovers have gone home it is a good place to take an evening stroll.

Ceramics towns

Manises ™ [map], next to Valencia’s airport, has been synonymous with ceramics since the Moors introduced the craft. The Museo de Cerámica de Manises (Tue–Sat 10am–1.30pm and 4–7pm, Sun 11am–2pm; free) has a permanent exhibition of 2,500 pieces dating from the 14th century to the present day. It’s worth taking a stroll around the old town to browse in the ceramics shops and to see some beautiful tiled façades and colourful door jambs.

There are more ceramics in Tavernes Blanques, a short way north of the city, where the Lladró company has its factory and the Centro Cultural y Museo Lladró (Mon–Fri 9.30–6pm, Sat 9am–2pm; free). Visitors see the whole process from design to the kiln, together with an exhibition of current and past products. The Lladró brothers’ art collection – including works by El Greco, Sorolla, Zubarán Ribera and other Spanish artists – is on display in a separate hall.

El Puig Monastery

Corbis

El Puig Monastery

About 15km (9 miles) north of Valencia is the Mercedarian Real Monasterio del Puig de Santa Maria # [map] (Tue–Sat 10am–noon and 4–5pm, Sun at noon, beginning on the hour; visit by guided tour only, book by calling 96 147 02 00 or e-mail mercedariospuig@gmail.com; charge). In 1237, on the eve of the conquest of Valencia by the forces of King Jaime I, a statue of the Virgin Mary was found on a hill on this spot. A church was built to house the statue, which was adopted as the patroness of the new Christian kingdom. In 1588 the church gave way to the monastery, a forbidding rectangular building with four stout corner towers. The guided visit takes you through two cloisters and into the refectory, chapel, hall and other rooms where there are numerous works of art.

In one wing is the Museo de la Imprenta y de la Obra Gráfica (Museum of Printing and Graphic Arts), which has a facsimile of what is thought to be the first book printed in Spain: Les Obres o Trobes en Lahors a la Verge Maria, printed in Valencia in 1474.

Excursions

Many varied but little-known places are within reach of the city of Valencia, especially if you have hired a car – although most can be reached with public transport. The easiest to get to are on the coast, or at least on the coastal plain. The nearest of them are still in Valencia province, but rewarding one- or two-day excursions can be made northwards to the Costa del Azahar, the coast of Castellón province, and south towards Alicante and the Costa Blanca. Below are the nearest and most worthwhile destinations for a day out.

Sagunt

In 219BC, Saguntum, a Roman outpost on the Via Augusta whose foundation long predates Valencia, was sacked by the Carthaginian general Hannibal, an attack which was to spark the Second Punic War and lead to the subjugation of Spain by Rome. Among other monuments, the Romans built a theatre on the hillside above the present-day town of Sagunt ¢ [map] (30km/18.5 miles north of Valencia by road or rail), exploiting a natural hollow for its acoustic effects.

In 1896 this theatre was the first building in Spain to be declared a national monument. In the 1980s the decision was taken to rehabilitate it for contemporary performances of drama and music, but the restoration work made controversial use of new materials and techniques and not everyone has been happy with the result.

On the crest of the hill above is a sprawling castle, which from the 5th century BC was the site of the Iberian settlement of Arse. Over the centuries it was added to by successive civilisations. Almost 1km (0.5 mile) in length, it is divided into seven plazas or divisions. There are beautiful views from it over the town and the sea. (The castle and Roman theatre are open Tue–Sat 10am–6pm, till 8pm in summer, Sun 10am–2pm; free.)

Below the theatre and castle, the core of the old town is medieval, set around the porticoed main square. The most atmospheric part is the old Jewish quarter, which is laid out in irregular narrow streets and passageways.

Peñiscola, viewed from the Knights Templar castle

iStock

Peñíscola

In the extreme north of Castellón province is the old fortified town of Peñíscola (140km/87 miles north of Valencia on the A7 motorway), built on a rocky promontory into the sea. Its castle, the Castell del Papa Luna, erected on the foundations of a Moorish fortress, is mainly the work of the Knights Templar and their cross can be seen carved above the door. It later became the residence of the papal pretender Pedro de Luna, cardinal of Aragón, who was elected Pope Benedict XIII during the Great Schism that split the Christian Church at the end of the 14th century. He retired here after he had been deposed and died a nonagenarian in 1423 still proclaiming his right to the papacy. The castle was used as a location for the film El Cid. Beneath the castle walls is a delightful labyrinth of steep, narrow cobbled streets lined with white houses, enclosed by massive ramparts and entered by two gates.

To the north of the old town is an immensely long, straight sandy beach stretching to the next resort of Benicarló. There is also a smaller curve of beach to the south, next to the harbour.

Gandía

The Duchy of Gandía ∞ [map] (65km/40 miles south of Valencia by the A7 motorway) was bought by one Rodrigo Borja in 1485. As Pope Alexander VI he founded the clan known better by the Italian spelling of its name, Borgia. He himself is remembered for his scandalous private life, but his illegitimate son, Cesare, and daughter, Lucrezia, have become definitions of debauchery. The family’s reputation was redeemed by Alexander’s great-grandson, who was born in Gandía in 1510 and canonised in 1671 as St Francis Borgia. Following the death of his wife, he turned his back on the pleasures of the world, joined the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) and devoted himself to spreading the ideas of the Counter-Reformation.

The built-up beach at Gandía

123RF

For all his saintly work he remained a nobleman and his birthplace, the Palacio Ducal (Duke’s Palace; Mon–Sat 10am–1.30pm and 3–6.30pm in winter, Mon–Sat 10am–1.30pm and 4–7.30pm in summer, Sun 10am–1.30pm; www.palauducal.com; charge), is an opulent building inside, even if no hint of this is given by the simple Gothic courtyard you enter by. The interior decoration, with its painted ceilings and gilded doorways, reaches a zenith in the baroque Golden Gallery, commissioned by the 10th duke of Gandía to celebrate his ancestor’s canonisation. One room on the tour has a concentric circular tiled floor made in Manises representing the four elements of earth, air, fire and water. Gandía has some beautiful sandy beaches and is known for its typical dish, fideuà, a kind of paella made with vermicelli instead of rice (for more information, click here).

The upside-down King

Xàtiva was a prosperous place until, as part of the kingdom of Valencia, it backed the losing side in the War of the Spanish Succession, that of Archduke Charles of Austria. Retribution followed the Battle of Almansa in 1707, when the victor, Felipe V, burnt down the town and renamed it San Felipe. In the 19th century, the city fathers reclaimed the old Moorish name and exacted their revenge by hanging Felipe’s portrait upside down in the municipal museum – and that’s the way it has remained.

Xàtiva (Játiva)

You can follow the Borgia line backwards by going inland from Gandía to Xàtiva § [map] (60km/37 miles southwest of Valencia), the birthplace of the two popes who founded the clan. The Phoenecians are thought to have first settled the site. In the 11th century, Europe’s first paper was made in Xàtiva by the Moors out of rice and straw. A huge ribbon of a castle (Tue–Sun 10am–7pm, closes 6pm in winter; www.xativaturismo.com/castell-de-xativa/; free on Tue afternoon), with 30 towers, once the most important fortress under the Crown of Aragón, runs along the ridge above the town. On the way up to the castle are two very old chapels: the 13th-century San Feliu (St Felix; Tue–Sat 10am–1pm and 3–6pm in winter; 10am–1pm and 4–7pm in summer, Sun 10am–1pm), which has a Romanesque doorway, pink marble columns and paintings from the 14th and 15th centuries, and San José (Tue–Sat 10am–1pm and 3–4pm, Sun 10am–1pm), which has a viewpoint outside it.

Among the sights in the narrow streets and small squares of the old part of the town are a former hospital with a Plateresque façade (opposite the 16th-century collegiate church), and a medieval fountain in Plaça de la Trinidad. The municipal museum Museo del Almodí (Tue–Fri 10am–2pm and 4–6pm; Sat–Sun 10am–2pm; free on Sun), meanwhile, has an unusual royal portrait in its collection.

Denia and Jávea (Xàbia)

The two closest resorts of the Costa Blanca to Valencia are Denia (100km/62 miles south by the A7 motorway) and Jávea (10km/6 miles further), separated by the humpbacked hill and nature reserve of Mount Montgó (753m/2,470ft). They are very different in character from each other and between them offer a range of beaches.

The bigger and busier of the two is Denia, which was founded as a Greek colony and named after the goddess Diana. For a while in the Middle Ages it was the capital of a Moorish kingdom and the oldest parts of its castle date from that time. North of the harbour, past the old fishermen’s quarter, is the long, wide sandy beach of Las Marinas; to the south is the more discreet and rocky Las Rotas, which has some good snorkelling. In the first two weeks of July Denia holds its Toros a la Mar festival, a bull-run up to the water’s edge.

Raisin’ the roof

Many of the older houses in the countryside surrounding Jávea have an unusual feature testifying to the local land use: a riu-rau, an arched stone porch where grapes were hung to dry into raisins in the circulating air.

Jávea, over the hill, is in two parts. Its town centre is perched on a hill a short way inland, on the site of an Iberian settlement. Many of the buildings lining the streets – including the town hall and cinema – are made from the local characteristic tosca sandstone. The 16th-century church of San Bartolomé is an imposing piece of work as it was fortified to serve its congregation as a refuge in times of invasion. Over the door are machicolations through which missiles would be dropped on to attackers.

Jávea cove

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Most buildings around the port and main beach, which are overlooked by a line of ruined 17th- and 18th-century windmills, are modern but relatively low-level as a result of council policy to keep Jávea from being dominated by the high-rise apartment blocks seen in other resorts.

The rest of Jávea’s shoreline is rocky. Pirates and smugglers once took advantage of the hiding places afforded by the cliffs, caves and inlets between the lighthouse at Cape San Antonio and Granadella Cove.