4

Not Like the Old Man Anymore

FACED WITH AN ABSENCE of nearly two years from the stages of New York City, the Keatons played the Orpheum time and found bookings wherever they could. “If nothing takes place will leave here quick,” Joe wrote a cousin from Chicago. “Must have work.” Things picked up again, and the family contemplated a long summer’s rest in Muskegon. Then, as if to prove her mettle as a Keaton, little Louise marched out of a French window on the second floor of Ehrich House and managed to survive the fall with severe facial lacerations and a dislocated jaw. Gathering her up in her arms, Myra commandeered a horse and buggy and rushed her to the hospital. “The doctors massaged her jawbones back into their sockets,” Buster remembered, “and sewed up her tongue which had been all but cut in two.” Two weeks later, Billboard reported her as having fully recovered from her injuries, and that she could “talk as well as ever.”

Any calamity, real or imagined, was grist for Joe Keaton’s publicity mill. Chastened by the debacle of the Jingles kidnapping plot, he stuck with fanciful tales of life on the road. One evergreen, which he fed to local newspapers on countless occasions, concerned the saving of his family from a terrible death. En route to New York, the story went, the Keatons’ train stopped at Elizabeth, New Jersey, where the brakeman announced a twenty-minute delay. The family repaired to the lunchroom, and Joe, who finished first, stepped outside to wait. Attracted by a sign that read SALOON, he hastened to wash down his lunch with a mug of beer. While inside, he heard the conductor call “All aboard!” and made it to the platform just as the train was pulling away. Surrounded by Myra and the kids, he soon received word that the train had run into a ditch. “Thus,” the item concluded, “did father save his family through the kindly offices of a glass of beer.”

Another had Joe pawning his wife and infant child in Missouri when the show went broke and he couldn’t cover a hotel bill. Leaving Myra and Buster as collateral, he set off by himself to earn their ransom, failing miserably. In his absence, Myra fell ill and was methodically picked clean of her jewelry by the landlady, who also took the baby’s necklace. Eventually Joe was able to make good and come up with the cash, and the family was reunited at some remote locale. “The door receipts for that night were just an even $7, lucky number. Now nothing can separate the family and two more little Keatons have been added on the register of the hotel to have their bill settled.”

Still another concerned the very real threat of hotel fires, with Joe claiming that he and the family had survived three inside of fourteen months. He always managed to get his loved ones out safely, the story went, and had always been able to save something—and that something was always the same. “When they had all got down the fire escapes, and had reached a place of safety, Joe would find clutched tightly in his hand—a cake of soap.”

When the Keatons returned to Muskegon in July 1908, big things were happening. Plans were under way for a hotel that would, in the judgment of The Muskegon Daily Chronicle, give “the finishing touch” to the shoreline as a summer resort. Meanwhile, a strip of land along the western shore of Muskegon Lake was being platted to create forty-four lots. “This property seems to be an ideal site for summer homes for those who want to be in close touch with the city and still enjoy the benefits of lake breezes and a location near a lake; who are looking for all the pleasures of a summer without being more than a few steps away from a street car line.” According to the Chronicle, more than half the lots had already been disposed of to buyers who planned to build.

Joe Keaton, along with fellow vaudevillian Paul Lucier, was in the market for plots in what he hoped would become a genuine actors’ colony. “There were about eighteen or twenty vaudeville actors living there with their families,” Buster said. “That meant Mom could play all the pinochle her heart craved and Pop would not run out of fellow performers to swap yarns with.” Having initially committed to four lots in the new development known as Edgewater, Joe worked a deal with real estate agent C. S. Ford to sell the remaining inventory on a commission basis during the upcoming season.

“The result,” the Chronicle reported on October 10, “has been that the agent has heard from Mr. Keaton every week, and every week has brought another sale or two. This week the Keatons were at Union Hill, N.J., having been booked in for a number of weeks playing eastern time. While playing at Union Hill, Mr. Keaton sold two lots to T. Kay Smith, a monologist, who plays next week at Johnstown, Pa. Last week he sold four lots to Frank Rae of Rae & Broche. Mr. Rae will have his cottage erected next spring and early in the summer will bring his $1,500 launch around from New York City via Buffalo and the lakes.”

By the end of October, all but two of the original forty-four lots had been taken, the latest purchasers being Tudor Cameron of the song-and-dance team of Cameron and Flannagan; Bonnie Gaylord, Cameron’s wife; and a British comedian named Harry Piquo, who bought four lots. When Joe finally took full account of his commissions, all carefully tallied by Myra, he was able to claim six prime lots he had set aside for himself, the titles for which were recorded on December 11, 1908. The following day, an uncommonly carefree verse occupied Joe’s usual ad space in the Clipper:

Next year, in October, there’ll be a fluster,

Because of the sixteen Summers of Buster.

Till then us for the leafy bowers!

Gerry Society please send flowers.

The Keatons laid off for the Christmas season, hitting the road again on December 28 and playing stands within short jumps of New York City—Reading, Wilmington, Union Hill, Harrisburg. Then they headed south to Alabama, Arkansas, Texas, and Georgia, Buster booking all the travel himself and keeping track of the family’s room-and-board expenses in a special pocket-size datebook. At age twelve, he loved being treated as fully grown and the equal of all the other performers on the bill. “Isn’t that what most children want: to be accepted, to be allowed to share in their parents’ concerns and problems?”

Advance press included a photo of the four eldest Keatons, each costumed exactly alike, stairstepping downward from Joe to Jingles, the billing “The Four Keatons and Buster” justified by two-year-old Louise’s appearances at matinee performances. Eager to commemorate Buster’s elevation to theatrical adulthood, Joe announced in the trade press that the Keatons would return to the New York stage on the very day of the boy’s emancipation, October 4, 1909, at Keith & Proctor’s Fifth Avenue. In May, the family traveled to Muskegon, where a six-room Keaton bungalow would soon rise on a prime lot at the base of a giant sand dune known as Pigeon Hill. It was while the Keatons were in residence at Muskegon that a letter arrived from England, addressed to Joe in care of Frank “Bullhead” Pascoe, whose saloon served as a sort of branch post office for many of the seasonal residents. As Joe later recounted it, the letter was from Alfred Butt, the manager of the Palace Theatre of Varieties in London’s Cambridge Circus, offering the Keatons a week’s engagement at £40 (roughly $200 and below the act’s usual figure). It also said that if they were willing to make the jump, they could stay there indefinitely “if there was any merit” to their act.

Joe, of course, had been keen on playing abroad for years. “I am getting the European fever my self,” he wrote Harry Houdini in April 1901, “and should I be lucky enough to land about a 12 weeks run, I am the lad to take a chance….In fact I am very anxious to get over there in Oct[ober] or later. And I want you to be my assistant Manager. You can’t talk to[o] much on the ability of my little comedian Buster and our Comedy Table work. There ain’t another act like it. And my Sal[ary] is 225 for 12 weeks or more.”

In 1905, Joe announced the family would spend much of the following year playing “the leading music halls through the English provinces, Ireland and Scotland,” but scuttled the plan when work at home proved so plentiful and Myra’s pregnancy intervened. In subsequent years, his wanderlust subsided as he grew to like the occasional holidays they took. Still, it was a temptation to finally see the British Isles. “I had $1,400 in cash at the time I received that letter,” Joe recalled. “So the journey commenced.” Back in New York, he went to a steamship agent on Fourteenth Street to purchase tickets, and ran into actor Hal Godfrey, who was there changing money.

“What are you doing here?” Godfrey asked.

“Going to London,” Joe replied.

“Oh! Mercy on you, Joe. I’ve just got away.” And Godfrey made his exit with a look of pity on his face.

Deflated, Joe asked if he could get his money back, only to be told that the deal had been made. “That night, one friend would sympathize; another would say: ‘Go to it, old man; it’s opening up a new field. You’ll be a riot,’ but what Hal said was most prominent. I went home and told the family London was all off. That started something. Tears streamed down little Buster’s face; Mother’s too. Visiting friends said: ‘Don’t disappoint Mr. Butt, manager of the greatest music hall in the world.’ So they persuaded me to go.”

They made the crossing on the SS George Washington, a new luxury liner built by the Germans on a grand scale. Fussing all the way, Joe later claimed he did everything he could to get thrown off the ship, even making an attempt to sell Louise off as an “orphan child,” a gambit that came close to causing a scrap. “But they wouldn’t put me off the boat. Instead they told me that if I tried to auction off any more babies they would put me in irons.” He resigned himself to the trip, and celebrated his July 6 birthday at the captain’s table. Exiting the boat train at Paddington, they were met by Walter C. Kelly, vaudeville’s famed Virginia Judge, who had arranged for lodgings. (It was Kelly who induced Butt to offer the Keatons an engagement in the first place.) After a chaotic four-mile cab ride and a generous round of American-style tipping, all passengers and luggage were delivered to what Joe sourly deemed “a questionable place.” The next morning, they called on Mr. Butt at the elegant Palace Theatre, originally commissioned by Richard D’Oyly Carte as a home for English grand opera. The Keatons, Joe noted, were completely unbilled. (“Not even a photo out.”) When he asked the stage manager for an explanation, the man simply said he had no time to argue.

At rehearsal, Joe presented the house conductor with “a nice set of orchestrations” from the American music publisher Fred Helf, particularly a beautiful overture. The first number went well.

“But when mother pulled the saxophone [out] you could hear them all through the pit. ‘What the blooming hell?’ said one. ‘Are they going to play that?’ ‘I never saw one in tune in my life,’ said another. By that time, mother had broken down. I was trembling and all I could think of was Hal Godfrey. Rehearsal over and no ‘props.’ We need brooms, a chair, pistol, gong; any old Mammy has them in her log cabin. They couldn’t get them.”

The stage was full of traps and splinters, forcing Joe to dial back some of the physical business for the sake of his son’s hide. “Pop couldn’t use me as a human mop,” Buster said, “but he had his usual fun throwing me into the scenery and out through the wings.” It was only a minute or so before they had the crowd laughing. “Nine-tenths of the time I was in the air and the rest of it, on my neck. Joe gave me the works.”

“They went very well with the gallery,” said William “Billy” Gould, the London correspondent for Variety. “In fact, I never heard before [a] gallery so insistent for an encore. They applauded and hollered ‘Encore!’ for fully three minutes, but the stalls were quite reserved….I predict that the Three Keatons will be a riot in the provinces or in any of the London halls, barring the Empire, Alhambra and Palace.” Gould was standing alongside Butt at the rear of the house.

“Fine applause,” he remarked. “Why don’t they allow them a bow?”

Butt wouldn’t permit it. “It isn’t on the level,” he said.

The following night, the manager moved them up so early on the program there was virtually nobody on the lower floor or in the stalls. It took their friend Kelly to explain the problem with the people who frequented the higher-priced seats. “You actually scared the audience,” he told Joe. “They think you are hurting Buster. The act is too brutal for them.”

The next morning, Butt called Joe into his office. “I shall ask you,” he said. “Is that your own son or an adopted one?”

Joe told him that Buster was his own son.

“My word!” Butt exclaimed. “I imagined he was an adopted boy and you didn’t give a damn what you did to him.”

That same day, Joe furiously booked return passage, abandoning all hope of spending more time in Great Britain. “We could book up three years if we wanted to stay,” he fumed, “but the boat would sail Tuesday rather than Wednesday if I had my way.”

Buster was just as adamant: “Coming back in a hurry,” he wrote a friend in Muskegon. Upon arriving in New York on July 28, Joe promptly vented his disgust to Variety and the Dramatic Mirror, saying he hated the food and the warm beer, while taking care to acknowledge the hospitality of the American players who were “bully and did everything in their power” to make their short stay a pleasant one. “The day we sailed from God’s country,” he added, “my father died and I never knew of it until I came down the gangplank again, once more back home—and believe me I am a better Yankee than ever I was before.”

Back in Michigan, the Keatons took possession of their new Edgewater cottage, the first home they had ever truly had, which, Buster estimated, “couldn’t have cost more than $500.00 to build.” Joe christened the place “Jingles Jungle” and nailed up a sign to that effect. More vaudeville stars had joined the actors’ colony, the latest being the Four Floods, an acrobatic troupe looking to retire on twenty acres of land on the north shore of Muskegon Lake. (By now, Joe was such a booster that Variety began spelling the city’s name “Muskeaton.”) The August exodus of resorters had already begun when Joe caught a string of forty white bass in the lake, one of the best hauls of the season. Proudly posing for photos, he vowed to use some of the shots in his trade ads, further burnishing the allure of the place as a summer destination.

The Keaton family at their summer cottage in Bluffton. From left: Louise, Harry, Buster, Myra, and Joe, who christened the place “Jingles Jungle.”

Newly energized, the Keatons opened their 1909–10 season on August 23 in Philadelphia, where they bested headliner Pat Rooney, who was appearing in a farce comedy titled Hotel Laughland. “Joe Keaton and his whole family certainly never went better than they did today,” manager C. H. Barns reported. “He is not handling the boy as roughly as he used to, and there is no end of fun right from the first. Little ‘Jingles’ caught the crowd very strong, and in fact, the act was a scream all the way through. [It is] now one of the best knockabout acts in vaudeville, and appeals to the women and children particularly.”

Leading up to Buster’s grand reemergence in Manhattan on October 4, Joe composed an autobiography in rhyme and began serializing it in Variety. Under the title “The Origin of the Three Keatons,” the first entry was published on September 26:

A fellow there was who hailed from the west,

Who once drove an old prairie schooner,

Who has the right dope but hit the wrong trail—

This thin Oklahoma boomer.

He sit one day in front of his shack,

With an old faded circus poster,

And grinned as he looked at the comical clown,

And wished he, too, was a joker.

The series stretched into November, by which time Buster’s birthday had passed but not without incident. Having intended for half a year to reintroduce the act at Keith & Proctor’s Fifth Avenue Theatre, Joe learned that house manager G. E. McCune was planning to have them on first. Angrily, Joe canceled the booking, berating agent Eddie Keller for abetting such an insult. On short notice, he picked up two weeks with Mike Shea and directed Keller to find them another house in New York City, the result of which was that Buster actually turned fourteen on a stage in Toronto.

Meanwhile, the new booking Keller secured was a happy outcome, for Hammerstein’s Victoria, which billed itself as “America’s Most Famous Variety Theatre,” constituted the absolute pinnacle of vaudeville in the days before the Palace eclipsed it. The young man who took the Victoria’s stage on October 18, 1909, was not much different from the five-year-old who made his New York debut at Proctor’s 125th Street in 1901. Time had increased his size, but he was still shorter than his mother, who at four feet eleven had several inches on him. In terms of makeup and costuming he remained the mirror image of his father, but the face under the greasepaint now displayed the high cheekbones and chiseled good looks of a cigar store Indian. And where in earlier years he could sing pleasingly, he was now prone to recitation with musical accompaniment, a result of his voice changing and “rasping like a phonograph when the needle is not working well.”

Finally freed of the threat of arrest, Joe, Myra, and Buster Keaton were seen with greater frequency in New York City, playing a total of six weeklong stands in Manhattan and Brooklyn during the first four months of 1910 alone. On April 20, while the family was appearing at the Star, the first of two back-to-back engagements in Brooklyn, the local Elks lodge tendered Joe a testimonial dinner, a kind of commemorative celebration of The Three Keatons over the previous decade, during which they had climbed from obscurity to become one of the standard acts in vaudeville. Joe took the opportunity to spin tales of the boom days in Oklahoma, leading to a loosely truthful account of the time he met his wife and got up a sketch that became the framework of the present act. It was an evening in which Buster was on prominent display, pledging to join the Elks as soon as he was of age but, given the timing, also effectively signaling an end to the act as the public had come to know it.

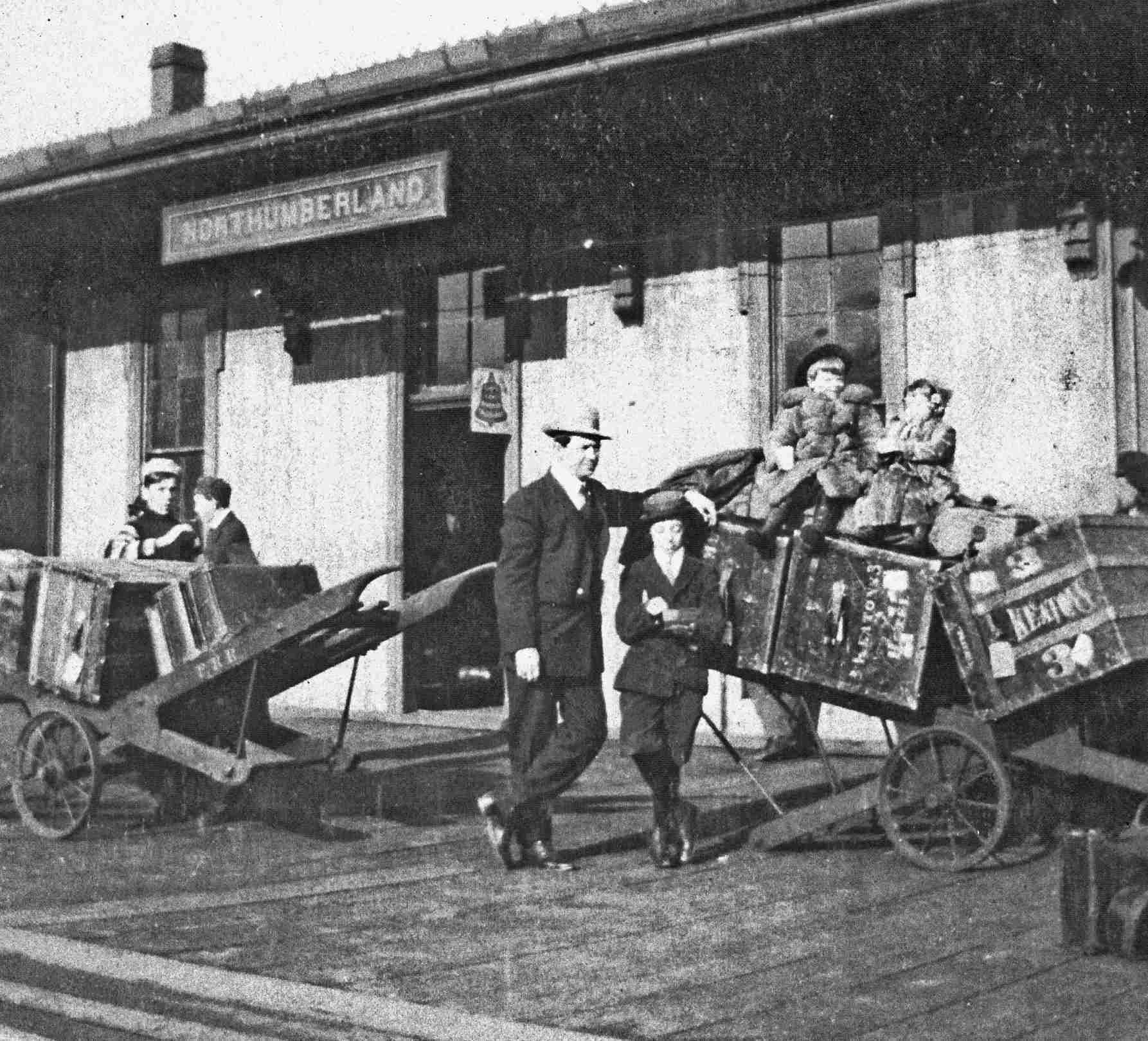

The Keatons on the road, circa 1910.

The transformation began with the abortive trip to England and the reaction in the stalls to the act’s apparent brutality. As the week progressed, Joe and Buster backed off on the freewheeling violence and managed to strike a more pleasing balance between mayhem and entertainment. Once home, they stuck with the new formula and found it worked even better than the old, the governing theme the same as always, that Buster “must behave.” Then, in making a jump between Pennsylvania’s Union Hill and Harrisburg in February 1910, both Joe and Buster were reportedly injured when a freight engine of the Pennsylvania Railroad jammed into the rear of their sleeping car. Press accounts had Joe, who was shaving at the time, losing three teeth in the jolt, while Buster suffered a concussion and an unspecified fracture. Years later, Buster said they hadn’t been hurt at all, and the record shows the Keatons opened as scheduled at the Harrisburg Orpheum that same day.

What actually came of the pileup of passengers, grips, Myra’s saxophone, Joe’s old Blickensderfer typewriter, and the like was a new bit based on the premise of Joe staring into a little travel mirror, his face generously lathered, shaving himself with a wooden straight razor. As Myra plays the saxophone, oblivious to the action around her, Buster ties a long rubber rope to a hook above the mirror. With his basketball tethered to the other end, he walks the full length of the stage, the line getting unbearably taut, the crowd’s laughter building with every step. “I let him have the basketball in the neck and—bop!—he gets his face slammed into the mirror and looks like a custard pie had hit him. Always had to remind him to go into the routine—he hated the taste of soap. So I’d remind him out loud, and he’d crack, ‘Are you trying to tell the author what to do?’ ”

Another new piece of business had Buster fighting off an attacker, only to reveal the struggle was actually with himself. “I used to do a thing comin’ out of a set house door of the stage,” he said during an interview for Canadian TV, acting it out, “and we’d grab the piece of scenery here comin’ out or hold the door here and my own hand on my neck. And from the front, it looks like somebody has got me by the neck. And I’d yell blue murder and shake the scenery and everything—and with my feet going in all directions. And my old man comes up there to free me. And he used to kick over my head, and his foot would come down there and knock me loose from there. And as I’d slid back across the stage this way, he saw that it was me who had a hold of myself, and he’d chase me right out of the theater, see.”

It was soon decided that Jingles, who did a little dance in the act and stood on his head, would leave the stage at age six to begin school, and that Louise, whose stage name was Joy, would vanish behind the scenes completely until she too was ready for classes. “The next five years—what years!” Buster exclaimed. “Sending the kids off to school one by one, Jingles to that Kalamazoo military academy and, later on, Louise to a Muskegon school. That brought the three of us back together again—the original three who went through all the hard times together. Success, sure. Money, sure. But this was the old times.”

Something else was happening. Joe Keaton, at age forty-three, was beginning to feel his years after a lifetime of hitch kicks, jumps, tumbles, and the hard physical labor of touring the circuits with one of the most rigorous of all knockabout turns. “In his efforts not to be violent with [his] son,” went a contemporary press account, “Papa Joe steps into Buster’s face from a chair on top of a table and leads him around by the lip. Papa Joe and Buster open with a soft-shoe dance while singing ‘I’m the Father of a Little Pickaninny’ except that they substitute ‘Acrobat’ for ‘Pickaninny.’ ” As the onstage action stretched to thirty minutes or more, Myra’s saxophone specialty became a necessary rest period for Joe, a few minutes when he could collapse backstage and marshal his strength for the second half. And where before he was principally a beer drinker, Joe had more recently taken to whiskey, relegating the lagers he formerly favored to supporting roles as chasers to the hard stuff.

Tired of traveling, Joe kept the act in the vicinity of New York City, where he could return home at night to the familiar comforts of Ehrich House and hang out with his pals at the Vaudeville Comedy Club, a group of kindred souls that limited its membership to comedians, monologists, pantomimists, and comedy acrobats. For 1910, the family’s summer sojourn to Muskegon began May 5 and stretched into August.

“By golly, we got here after passing through some awful weather,” Joe reported in a letter dated June 7. “And I brought with me the season’s first sunshine. Found my case of Green River waiting here for me.” Green River was a connoisseur’s drink, the “whiskey without a headache” that “blots out all your troubles.” Wrote Joe: “I have the finest location on this lake and every comfort for the weary and inner man.”

When the Keatons opened their season in New York at Hammerstein’s, a leaner, more varied act was on display, one that depended less on Myra than ever before.[*1] “Buster and Joe whooped it up some for twenty minutes or more,” Variety’s Dash Freeman recounted. “Buster is becoming a big boy, but Joe is still able to throw him about, and the kid is fast developing into a first-rate tumbler. A bit of new business with the brooms is extremely funny. Father and son have lots of fun with it.” Brooms had always been part of the act—Buster made handy weapons of them—but the new business put them in the hands of both combatants. As they squared off, mercilessly trading whacks with rhythmic zeal, the orchestra picked up on the cue and flew into Verdi’s “Anvil Chorus.” Buster credited the innovation to Joe’s penchant for punishing him onstage, in this case because the old man discovered a pipe in his jacket and considered him too young to be smoking. “And they always told me that my own mother began rolling her own at fifteen,” he said. “And when he [later] found the cigarettes, the tune was ‘a man smokes a pipe.’ Well, we gave the comics a new routine that day of the pipe, and they’ve used it ever since.”

Buster in his more mature stage persona at the approximate age of sixteen.

Buster was hurtling toward adulthood. He bought his first automobile at the age of thirteen, a lightweight contraption with a one-cylinder engine called a Browniekar, and upgraded to a secondhand Peerless Phaeton—a seven-seater—the year he turned fifteen. He also began to grow, and was taller than his mother by the time he legitimately turned sixteen in October 1911. Sixteen or not, he was still a missile as far as Joe was concerned, although hefting him was becoming more of a strain. Just after Buster’s birthday, Joe famously pitched him for just about the last time. The scene was Poli’s in New Haven, a theater the Keatons knew well. New Haven was notorious in vaudeville for the rowdy Yale students who made great sport of heckling performers, but the place couldn’t be avoided if acts expected to play the lucrative Poli time in the states of Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Jersey.

At the performance in question, some undergraduates had positioned themselves in the front row so that whatever comments they made were within easy earshot of the stage. As the headliners, the Keatons went on next to last, having stopped the show the previous week at the Poli house in Hartford. The first segment of the act got over beautifully.

“Three in the front row begin ribbing us,” Buster remembered. “The old man stops and says, ‘If you want to be the comics, come on up here and we’ll be glad to sit down there.’

“ ‘Go ahead,’ they say. ‘You stink anyway.’

“Joe begins to come to a boil. ‘One more crack,’ he says, ‘and I’m coming over.’ ”

Myra emerged to play her solo, and the vigorous response was, in Buster’s memory, enough to rock the theater. As she took her bows, Joe stepped to the footlights and, giving the crowd a big wink, said, “Don’t spoil her, boys. She’s hard enough to handle now.”

“She stinks, too!”

That did it. Impulsively, Joe reached for the nearest weapon—which just happened to be his boy. Grabbing him by the nape of the neck, he said under his breath, “Tighten up your ass.” The next thing Buster knew he was airborne, hurtling toward the front row.

“He has to clear the orchestra pit,” Buster emphasized, marveling at the velocity of Joe’s throw. “The orchestra pit is six feet wide. Gotta clear that.”

In all, he traveled three, maybe four yards prior to impact. “[Hit ’em] broadside,” he said proudly. “Three of ’em.” The damage, he added, was considerable. “My slapshoes break the nose of one; my hips crack another’s ribs. I’m back up and on with the act before the ushers and cops get down the aisle. One guy had to be carried out.”

Joe’s confidence in Buster’s ability to safely land was once again justified. “The thought never entered his mind that I’d get hurt,” Buster said of the event. “He knows I’m all right.”

Joe Keaton was already looking to the day when Buster would go out on his own, effectively bringing the act known as The Three Keatons to an end. They had worked thirty-nine weeks over the 1909–10 season but cut back to just twenty-nine weeks for 1911–12. Nineteen eleven was also the year Joe announced he had purchased eleven lots on Muskegon Lake and planned to erect a summer hotel for actors on the site. (“Joe,” commented Variety’s Billy Gould, “will never be satisfied until he can play New York and sleep in ‘Muskeaton,’ Mich., nightly.”) Apart from fishing and piloting a twenty-five-foot launch dubbed The Battleship, Joe’s daily routine at Bluffton was hinted at in the lyrics of the “Actors’ Colony Clubhouse Song,” which he presumably had a hand in writing:

Meeting with the boys at Pascoe’s

at the closing of the day—

Syl and Bub and Clark and Keaton;

after all the fish were eaten,

we would go on our merry way—

Then when we would reach the clubhouse

we’d sing another song or two—

Then we’d drink ’til early dawn,

until all the beer was gone—

and go home to sleep at cock-a-doodle doo.

Buster’s affection for his adopted home was on full display in a datebook he kept, where a retreat to Muskegon was celebrated as “HOME” and frequently decorated with little sprite-like figures labeled “JOY.” Conversely, the late-summer return to work was accompanied by banners and figures sporting the word “GLOOM.”[*2] In between, he passed his days swimming and playing baseball, having formed a sandlot team initially called the Juniors, later the Colts.

“There was a bar in Pascoe’s Tavern, and a club to which all the actors belonged. As for me and the younger children, we just got into bathing suits each morning on getting up and never took them off until we went to bed.” Occasionally, he got stuck babysitting his sister when all he wanted to do was play baseball. “I used to fill her clothes with sand so she couldn’t crawl away. She’d sit there happily, scooping handfuls of sand out of her little skirt.”

An artist rendered highlights of the Keaton act once Buster had grown too big to blithely toss around. “The funny thing about our act,” Buster commented, “is that Dad gets the worst of it, although I’m the one who apparently receives the bruises. Dad has had a sprained wrist for years from throwing me. I’ve only been hurt a few times.”

At Bluffton, the Keatons gave little thought to the act, which remained a certified crowd-pleaser, even on the occasions when it stretched to thirty minutes or more. “This well-known family was a genuine hit,” reported W. W. Prosser, manager of the Keith’s Gay Street theater in Columbus, Ohio, “going bigger than at any time they have ever played this house. The audience howled with delight and, notwithstanding the unusual amount of time consumed, the act at no time became tiresome.”

The matter of Buster’s size was raised frequently as his seventeenth birthday loomed. “The same hit,” wrote Prosser’s counterpart in Cleveland, “but Buster is growing larger all the while, and it won’t be too many seasons before he’ll be throwing the old man around.”

Joe could still kick, but sometimes his aim was off. “He missed my hat once in New Haven [doing the self-struggle bit],” said Buster, “and got me in the back of the neck.” The boy fell backward and bounced his head on the floor. “I was out for twenty-two hours, Myra by the bed all the time. Concussion. Since he couldn’t throw me anymore, he began sliding me around on the floor. Like a human toboggan. That’s when I told a reporter that I’d given polish to the American stage.”

A manager’s report from Philadelphia in February 1913 assessed a new, leaner version of the act: “Although Buster Keaton is pretty nearly a full-grown man, nevertheless he keeps up the kid illusion very well, and the new material introduced in a measure takes the place of the former act when Joe could more easily throw the kid across the stage. It is really a very amusing act. Got plenty of laughter and applause and closed strong.”

It wasn’t so much getting even as a necessary shift in dynamics. From the beginning, it had been little Buster versus big Joe, David and Goliath. Then Buster turned eighteen and grew three inches in the space of a year. Suddenly the act was two adults giving each other comedic hell and showing no mercy. Buster remembered a particular matinee at Hammerstein’s when Joe lingered too long at a taproom down the street. “In his hurry he forgot to put on the felt pad he had been wearing under his trousers ever since I got strong enough to hurt him when we did our ‘Anvil Chorus’ work on each other with the brooms.” Buster gave him a good whack, and Joe turned green with pain.

“Christ!” he yelled. “I left the pad off!” And the audience roared at the language.

“Are you going through with it?” Joe asked him.

“Sure,” answered Buster. “It’s part of the play.” Whereupon he let him have it again.

“Going through with it?” Joe repeated.

“Yes,” said Buster firmly.

“But remember,” he appealed. “I’m your father.”

It made no difference. Buster laid into him, and Joe laid back. The orchestra launched into “Anvil Chorus,” and by the end of the bit Joe was black and blue. Staggering toward the audience, he delivered one of his most memorable ad libs.

“This is the last time,” he vowed in a stage whisper, “I let George M. Cohan write anything for me.”

In 1914, Buster purchased his own modest cottage at Bluffton, a half mile from Jingles Jungle, in the heart of the neighborhood. The place afforded him a measure of privacy while abetting an intense interest in the opposite sex. Joe had warned him to stay away from local girls lest someone’s father came around with a shotgun, but the one time he frequented a local bordello, he came away with an apparent dose of the clap that kept him out of commission most of one summer. (The problem was ultimately determined to be a pulled groin muscle, exacerbated by the home remedies and patent medicines he was given.) A neighbor girl, Mildred Millard (of the family act The Three Millards), could remember Buster sitting out the Friday-night dances at the park pavilion “in his old red sweater and khaki pants,” mixing with the other actors and keenly aware of Mildred’s father, sixty-four-year-old Leroy “Pop” Millard, who kept an eagle eye on him. Still, it was Muskegon that presented Buster with his first serious infatuation, an attractive girl from Chicago named Marie Boone. Myra felt sure the relationship would end in marriage, but the two eventually went their separate ways. “She wasn’t an actress,” was all Buster would say.

The season began late that fall, with Buster observing his nineteenth birthday in Davenport, Iowa, the first of a series of split weeks the Keatons played in Cedar Rapids, Springfield, Decatur, and Waterloo before heading on into New York. They laid off the entire month of December, and when they went back to work in January, it was with the knowledge that they would be spending the month of April in Muskegon so that Myra could undergo an operation.

It was too cold to swim, and there weren’t enough players to get up a game of baseball, so Buster applied himself to an engineering project so outlandish it would become something of a tourist attraction. The previous summer, he and a longtime neighbor, monologist Edward Gray, got up an act for the Elks benefit, calling themselves Butt and Bogany, the lunatic jugglers. It was a riot of sharpshooting and broken dishes, and it opened the show with earsplitting bravado. (The two later emerged in their regular personas, Gray appearing as the droll Tall Tale Teller in the seventh position with The Three Keatons closing.) The much older Gray astonished the audience with a burst of energy few had ever witnessed, since he was regarded as the colony’s laziest resident. So when Ed complained one day of being unable to find an alarm clock that could get him up at a decent hour, Buster saw a chance to create the automated house of the future.

First came the clock, which was augmented by what Buster called the Awakener. When the alarm went off, Gray would have thirty seconds to leap out of bed and silence it before a form of Armageddon would erupt. A series of weights and counterweights controlled by the clock simultaneously turned the gas on and ignited the burner under the coffeepot. Meanwhile, a mechanical arm plucked off the sheet and blanket, while the bed itself was made to rock as if an earthquake had hit. Other improvements followed. “Gray avenue is still one of the famous thoroughfares,” Billboard reported in July 1915, “and the Gray cottage is noted as the only house in the world in which everything is run on the automatic order. It is a center of attraction. Ed Gray, [theater manager] Tommy Burchell, and Buster Keaton have contrived to fix the house so the clock can be wound up simply by pressing a button. The house is known as the lazy man’s paradise, and even the flies are kept out by automatic device.”

Buster’s masterpiece was widely acknowledged to be Gray’s outhouse, which sat on a rise favored by picnickers and was commonly treated as if it were a public facility. He took the little building apart, anchoring its four walls at the base with spring hinges and sawing the roof in two. “I put a long pipe under the outhouse and attached a bolt. From the bolt I ran a line to Ed’s kitchen window, hanging on it some red flannel underwear and old shirts to make it look like a clothesline.” If Gray observed an unauthorized user from his window, he could yank the line at a well-timed moment and cause all four walls and the roof to fall away. Buster was so pleased with the result he eventually equipped the outhouse at Jingles Jungle to erupt in gunshots and fire bells whenever the chains dangling from a mock pair of tanks were pulled. This time, it was unnecessary to make the walls fall away; the victim would usually sprint through the door like a jackrabbit, achieving roughly the same effect.

Joe Keaton turned forty-eight on July 6, 1915, and the Actors’ Colony celebrated as if it were the biggest holiday of the year. Following a morning of baseball, during which the old actors’ team, the Muckets, trimmed the Colts 3–1, a parade of more than three hundred began a noontime march through the crooked streets of Bluffton, Joe and Myra leading it atop an elephant called Minnie from neighbor Max Gruber’s menagerie.[*3] They were followed by a fourteen-piece version of Wallace Ewing’s Zouave band, a Chautauqua favorite imported from Champaign for the day at fabulous expense. Then came a horse and Shetland pony, several trained dogs, and a host of other four-legged performers, all preceding the professional residents of the colony itself, actors of all stripes, including Buster and his pal Lex Neal, who meandered up into the grove at Lake Michigan Park and then down to the shore of Muskegon Lake, where they broke ranks and set off for Bay Mill, where an elaborate picnic spread awaited.

“Never in the history of the colony,” proclaimed an item in the Chronicle, “have so many actors been gathered together on the Muskegon lake shore.”

The birthday gala was one of the highlights of Joe Keaton’s life, an event where, as the paper put it, “every actor, no matter how big he is on Broadway, or any other way, nor how bold his name stood out in newspaper ads during the winter season, was a just plain actor…while Joe Keaton and Ma Keaton were the whole show.” But Joe’s time in the limelight was rapidly drawing to a close, and the 1915–16 vaudeville season would be the last full season for him and the family. Now approaching twenty, Buster had reached his full adult height of five six, but with his weight hovering around 130 pounds, he could still project the illusion of the underdog onstage. In movement he was angular and economical, as far removed from the average vaudeville comic as one could be. When thrown, he didn’t just hurtle through the air, he took flight.

“Any time that you leave the ground,” he liked to say, “it’s your head that will steer you.” And where Joe was all fury and instinct, Buster was a born actor, graceful and natural. Over the fifteen years he was part of the act, he never ceased perfecting the art of getting thrown around.

They spent the holidays in Muskegon, where Louise, age nine, was enrolled at the Ursuline Academy, a local boarding school for girls, and Harry, age eleven, was a cadet at Barbour Hall Junior Military, a Catholic boys’ school at Nazareth, some eighty miles southeast.

“The act had to change,” said Buster, “but Joe was changing too. Not like the old man anymore. Mad most of the time, and could look at you as if he didn’t know you.”

Myra urged her elder son not to take it personally. “It’s old Father Time he’d like to get his hands on,” she told him. “Man or woman, some can take getting old, some can’t.”

“It made it more understandable,” Buster conceded, “[but] no more standable. Anyway, like the Indian said, it went on like that for a while, then it got worse. When I smelled whiskey across the stage, I got braced.” To the outside world, and the trades in particular, the act was, in the assessment of Billboard, “better than ever.” Rolling into New York ahead of a stop at Keith’s Royal, they played a Sunday concert at the Columbia to a grand reception. The booking at the Royal, the new Keith venue in the Bronx, was prelude to the Keatons’ only appearance at the famed Palace, Martin Beck’s Times Square landmark that had become America’s premier vaudeville house in just three short years. Though formally known as B. F. Keith’s Palace, Beck, having initially built the place to anchor his eastern chain of Orpheum theaters, took a proprietary interest in the place and oversaw all aspects of its programming. Loud and gruff, Beck was never a particular favorite of Joe Keaton’s, but a Keith-Orpheum route had grown to mean forty to eighty weeks of straight time, a virtual bonanza for an act that could meet his exacting standards.

The matinee of April 24, 1916, played to an overflow audience, with the Keatons in the number three spot, following the Mutual Weekly newsreel and a colored musical act called the Royal Poinciana Sextet. Joe was already on edge over the billing, which placed them dead last in the print ads—if they were mentioned at all—and he blamed Beck for the slight. Still, they got over well with the Palace’s elite audience, at twenty-three minutes holding the stage longer than any other act on the program. It was the shuffling Beck did between the afternoon and evening performances that compounded the insult. Moving the headliner, actress Helen Ware, up with the early entries, Beck decreed the Keatons would now open the show, putting them on when the people out front were still finding their seats. “The Keatons were popular favorites with the few present at the early hour,” Variety’s Winn O’Connor reported. “Some corking good bits have been added to the comedy routine, particularly those utilized to cover the encore. The real value is lost, however, in such an early position, and a spot lower down would have doubly benefitted the act and the show.”

Joe stewed the rest of the week, gracefully accepting the handicap of the initial position while privately cursing Martin Beck for the disrespect he had shown. “Pop could not stop talking about this outrage,” Buster said. “He called Beck every name in the book.”

He finally boiled over one afternoon when, while onstage, he spied Beck standing in the wings, arms folded, glaring at him.

“Okay, Keaton,” Beck said in a harsh whisper, “make me laugh!”

Joe’s face turned purple with rage. “I’ll make you laugh, Martin Beck, you low-down, no-good bastard!”

The next thing Buster knew, Joe was racing toward Beck like an angry bull. “Beck ran, Joe right behind, out of the theater and up Forty-seventh Street. The stagehands tried to grab him and slowed him down a few seconds, and he lost Beck in the crowd. It was a good thing. He’d have killed him for sure.”

Left on the stage alone, Buster didn’t know what to do. He sang a song, did a jig, and offered a recitation until his father returned and the act could go on. Instinctively, though, he knew The Three Keatons were done for. The next day, Beck ordered the act shortened to twelve minutes, effectively destroying the momentum it built. Joe retaliated by elaborately winding a dollar alarm clock and, explaining the situation, setting it down on the Palace stage in front of the footlights. They began their turn, and when the clock went off, exactly twelve minutes in, they stopped whatever they were doing, no matter how riotous, and calmly walked offstage. And in doing so, the Keatons bid their farewell to the big time.

Effectively barred from the Keith-Orpheum circuit and the attendant services of the UBO, all the Keatons had left were the smaller independent circuits, regional in nature and considerably less prestigious. Within two weeks, Joe had signed with Joseph M. Schenck, general booking manager for Marcus Loew Enterprises, to open at Loew’s American Roof on Forty-First Street. Eager to bring major acts into the fold, Schenck paid them $300 a week, the same money they had been getting from Keith, and the Keatons delivered—the Clipper, for one, pronouncing them the hit of the show. (“Took five bows.”) Marcus Loew himself was considered the Keith of the small time, a square guy whose word was his bond, but outside of New York, Loew controlled only eight vaudeville houses, hardly more than a couple of months’ worth in terms of a route. And playing the small time meant giving three shows a day instead of two, something the Keatons hadn’t done in fifteen years. “The entire profession assumed you were on your way down—and maybe out—if you accepted small time booking,” Buster said.

Calling it a day, the Keatons fled to Muskegon for a long summer’s rest, Joe observing a twice-weekly route to the post office that included stops at the Occidental Hotel bar, the Elks lodge, and various businesses along Western Avenue. Accompanied by a reluctant Buster piloting either The Battleship or the Peerless, Joe would “pick up a letter or so, buy a two-cent stamp, and then [make] all the same stops over again working our way home.” There was a gala gathering at Edgewater on July 17 to say farewell to the ramshackle houseboat known as the Cobwebs and Rafters, Joe having donated the land for a new club headquarters to be called the Theatrical Colony Yacht Club (TCYC). The building, in the form of a commodious bungalow, was dedicated in early August, with the mayor, police chief, and a couple of aldermen officiating, and with Myra serving as president of the woman’s auxiliary. Joe, the steward for the TCYC, was also pitcher for the colony’s baseball team, while Buster served as catcher, shortstop, or utility man.

Come fall, their options limited, the Keatons signed with Alexander Pantages, a Greek immigrant in the process of building one of the most important independent vaudeville circuits in the nation. Working the West Coast and Canada from his base in Seattle, Pantages was in direct competition with Orpheum in a number of cities, and their rivalry had gotten so heated that Martin Beck issued an order that any act working the Pantages time was automatically barred from the Orpheum circuit. So, naturally, it appealed to Joe to lock arms with Pantages and blow a loud raspberry at Beck, their mutual enemy.

Pantages liked to roadshow his companies, meaning the program would remain fixed as it moved from theater to theater. Paired with the Keatons as the lead attraction would be a one-act musical-comedy titled Mr. Inquisitive featuring the husband-and-wife team of Earle Cavanaugh and Ruth Tompkins. Rounding out the program would be the ethnic comedy team of Rucker and Winfred, a pair of dancers known as Burke and Broderick, and Izetta, a lively ragtime singer who billed herself as the Eva Tanguay of the accordion. The company opened in Winnipeg on October 2, 1916, just two days prior to Buster’s twenty-first birthday, playing three shows a day—at two thirty, seven thirty, and nine o’clock. “Three-a-day with such a tough act wore Joe and Myra out, and got me down too—the bruises never got a chance to heal,” said Buster. “And now Joe was so sore that it was eating him up. ‘You think I’ve been drinking? Watch me now.’ ”

The Keatons made their usual hit. (“The intensely dramatic plot of one member trying to annihilate the other is well staged and nerve-wracking in its suspense,” commented a reviewer for the Free Press.) They were three weeks in Canada, making their way west to Calgary and Lethbridge, then down into Montana, where they spent five days working the Pantages house in Butte. It was a grueling route that incorporated a week of one-night stands, and Joe, now in his fiftieth year, was struggling to keep up.

“You have to say, ‘Poor son-of-a-bitch, fighting something he’d never catch up with,’ ” Buster reflected. “But, sweet Jesus, our act! What a beautiful thing it had been. That beautiful timing we had—beautiful to see, beautiful to do. The sound of the laughs, solid, right where you knew they would be…But look at what happened—standing up and bopping each other like a cheap film. It couldn’t last that way. Every time he got a snootful he’d sound off about Martin Beck. No matter who—agents, theatrical managers, anybody—tell ’em what he’s going to do to Beck. With his mind on Beck he’d come on the stage wild. That’s when I had to fasten a rubber rope onto that old basketball of mine and keep swinging it around like a hammer thrower to keep him off me. Get him running, let out the rope a little, and bop him on the fanny. There were times it was him or me, but we had to keep it funny—me on the old table like a ringmaster: ‘Hup, Prince! Hup, Prancer!’ Audience laughing like hell and my dad falling on his face.”

The tour continued into the holiday season, playing a beefed-up version of the bill in Tacoma, Portland, and San Francisco over Christmas week. The act, now reduced to sixteen minutes with Myra’s solo, was still the big noise in the closing position, but a shambles to anyone who knew the difference. It was that week in San Francisco that Buster told his mother, “I’m going to break up the act.” She made no objection. But how to tell Joe? “He would break down and cry like a baby, plead for another chance,” Buster said. “I was not prepared to watch my father go to pieces. I was not sure I could go through with it. Not that I wasn’t damn mad at him.”

The solution was not to tell him at all. As scheduled, they played Oakland the first week in January, then made the journey south to Los Angeles, where they were set to open at the Pantages theater on January 8, 1917. As Buster told it, he and Myra swiped their trunks from the alley out back of the theater, gave the manager some money for Joe, and ran. “As we say in the theatre, we left Joe with egg on his face. Left him with his trunk and the old beat-up table he had started with.”

Five days later, Buster and Myra Keaton were in Detroit, where she would be staying with friends. A few days after that, Buster left for New York, where he would seek out a new career for himself as a single in vaudeville.