8

The Most Unique and Original Comedian

BUSTER KEATON’S POPULARITY with audiences built so rapidly that by the end of the year 1920, just four months after the release of One Week, exhibitors across the nation were pairing The Saphead with The Scarecrow for an all-Keaton program, and Metro exchanges were supporting the trend by accepting bookings for the latter film long before its official release date of December 22. In New York, where the feature played the 5,200-seat Capitol Theatre, director Herbert Blaché’s habit of staging the action in long shots made, in Variety’s judgment, “the scenes look like miniatures and the characters like pygmies.” Notices were mixed, most finding the film an unsteady blend of drama and burlesque, with Buster being the only reason for sticking with it.

“The Saphead is a badly constructed photoplay, of course, with its jumping back-and-forth between self-styled serious comedy and extravagant farce,” offered the unsigned review in The New York Times. “And for this reason it is annoying to some, and would be to the writer if its farce were not so good. When he saw the picture he simply ignored its every pretension to verisimilitude, and sat back and laughed at Buster Keaton’s finished clowning. Leave only this clowning in the picture, with just enough of the stupid old plot to give it coherence, and you’d have one of the best broad comedies the screen could show.”

Keaton, having long since washed his hands of The Saphead, described its making in an interview as “a bore.” Instead, he indulged his gift for slapstick suited to the demands of the modern screen. The Goat, a slick tale of mistaken identity filmed largely on the streets of Los Angeles, was completed in January 1921. For it, Keaton brought a second director into the fold, Sennett veteran Malcolm St. Clair, whose résumé was similar to Eddie Cline’s and who would alternate with Cline for the foreseeable future. Tall and energetic, St. Clair had been the sports cartoonist for the Los Angeles Express before joining Keystone, where it was, he once said, “all gags and no sense.” Wielding a lighter touch than Cline, he might well have urged Keaton in a new direction had the two men been better suited to each other. Cline agreeably played a cop in The Goat while St. Clair enacted Dead Shot Dan, “a highly intelligent and kindly-faced murderer.” The finish sent an elevator containing Joe Roberts clear through the roof of an apartment building, Buster having established that he could control the speed and direction of the thing by simply moving the arrow on the dial above the door.

With The Goat finished, Keaton started on the eighth and final picture he owed Metro for the season, an untitled affair that advanced the automated house of The Scarecrow even further, using electricity to power the labor-saving features instead of pulleys and counterweights. He was shooting with Cline one day in late January when, while riding a mechanized staircase to the second floor of the interior set, the sole of one of his slapshoes got caught in the webbing that held the steps together. Thrown clear at the top, he fell twelve feet to the floor, breaking his right leg at the ankle. Rushed to Good Samaritan Hospital, it was estimated he’d be laid up for at least six weeks. In reality, it would be five months before he would be back at work again.

The immediate problem, that of delivering Metro’s eighth picture, was solved by taking The High Sign off the shelf. Not an ideal solution as far as Keaton was concerned, but Lou Anger never thought it as bad as its director made it out to be. It was imperative, though, to make it look like a new two-reeler, not some leftover or a trunk item. News of Buster’s injury was kept quiet, while word was put out to the press that his seventh comedy, The High Sign, had been completed and shipped to New York. As a further diversion, Variety reported that the entire Keaton company would be heading east in April, and that at least two pictures would be shot in New York City. Finally, on February 19, Camera! carried an item that Keaton would be unable to work for several weeks as a result of torn ligaments sustained in a scene. Two days later, The Haunted House was released nationwide.

Confined to bed and unable to work, Keaton was forced to confront the fact that his private life didn’t amount to a whole lot. Myra visited him every day, and he had pals like Viola Dana and Lew Cody stopping by, but up to the point of taking the house on Ingraham Street, he had led a transient lifestyle, content to sleep on someone’s couch rather than taking a place of his own. It was Bluffton where he spent his happiest days, and when a woman from Picture-Play came by for an interview, he showed her an ad for The Saphead from the Muskegon Chronicle, his name set in larger type than the film’s title:

Starring Muskegon’s Own

BUSTER KEATON

in his first big feature production

(Direct from the Capitol Theatre, New York,

where it played to Record-breaking houses.)

“Muskegon’s own!” he exclaimed. “Sounds like a bottle of catsup.” She naturally wanted to know if he had been born there.

“No,” he said, “but I lived there between seasons on the road and went to school—oh, it’s the old home town all right. I get an awful kick out of that ad.”

When news of the accident reached Natalie Talmadge in Palm Beach, where she was wintering with her mother and her sister Norma, she wrote Buster a letter: “I am alone now, the only one left living with Mother. If you still care, all you have to do is send for me.” His reply wasn’t immediate; he hadn’t seen her in nearly two years. After a few days of enforced solitude, he wired her that his leg wasn’t strong enough to go to New York, but that he’d be there when it was. Grace Kingsley broke the news on February 2 in the Los Angeles Times. “Some people seem to think the only way to capture those lovely Talmadge sisters is to strong-arm ’em,” Buster was quoted as saying, “and I don’t know but I may do that if necessary. That is, if nobody beats me to it with Miss Talmadge. New York, you know, is full of enterprising Greeks[*1] and Miss Talmadge is the loveliest girl in the world.”

Not to be outdone, the Herald tracked down Natalie, who just laughed and said, “There isn’t anything to tell.” Norma took the phone and explained that most of the courtship had been “conducted by telegraph.” In Muskegon, the Chronicle mistakenly characterized the relationship as a “war romance.” And in Variety, the deception continued with Buster supposedly “working a double production schedule out at the Metro” so that he would have time to fly east for the wedding. It soon became evident that Keaton wasn’t working, and that his salaried personnel were being loaned to other studios. Jean Havez was seen on the Lasky lot supplying bits for an Arbuckle feature, Joe Mitchell was loaned to Harry and Jack Cohn for work on their Hall Room Boys series, and Mal St. Clair was working at Fox after Lou Anger put out word that The Goat had been completed as Metro’s eighth and final release.

The Picture-Play interviewer, Emma-Lindsay Squier, asked Buster when he and Natalie were going to be married. “I don’t just exactly know,” he replied. “That’s up to my better nine-tenths—meaning Natalie—and, of course, the condition of my leg has something to do with it. I’ve been in bed now for five weeks, and the doctors think that I’m in for three more. Then I’ll have to dash around on crutches for a while—and after that—New York!” On March 23, it was reported the engagement was suddenly off. Natalie had broken it but refused to say why. One possible reason had appeared in the Los Angeles Times in late February, when the paper published a publicity photo of Keaton and Vi Dana on the Metro lot, demonstrating how a screen kiss was filmed for a group of visitors. The headline didn’t help: “HERE’S A REAL ROMANCE.” Neither did the subhead: “You Didn’t Know About It, Either.”

Two weeks later, sprung from the hospital and hobbling around on crutches, Keaton announced he was off to New York to collect his bride. He added that the wedding would occur almost immediately upon his arrival so that Natalie wouldn’t have any time to change her mind. Accompanying him would be Lou Anger, who would serve as best man at said wedding. In Manhattan, Billboard’s Marcie Paul went to the Forty-Eighth Street studio to get a look at Buster’s intended and found “a slim little dark person, wholly adorable, and unmistakably a Talmadge.” There was, she noted, no engagement ring. “Natalie doesn’t know when they are going to be married, because she doesn’t know when they are going to see each other again, and she doesn’t like to talk about things before they happen.”

Buster’s arrival came at a time when both Norma and Dutch were ill—Norma slightly, Dutch somewhat more seriously—and Nat was understandably distracted. “She had only one objection to marrying me,” he said. “She hated to leave New York, something that was not hard to understand.” The cloud of indecision lingered more than a month, during which time The High Sign was released to a better reception from audiences and exhibitors than its maker ever expected. (The New York Times found it “ingenious and irresistibly funny.”) To continue the ruse that it was newly made, Eddie Cline’s name was added to the credits, and a press statement explained away the absences of Virginia Fox and Joe Roberts by noting that even actors and actresses were entitled to vacations. “Such is the belief of Buster Keaton, Metro comedy star. As a result, The High Sign, the latest Keaton comedy, will make its appearance with an entire new cast supporting the sad-faced comedian.”

Six releases in, Keaton’s stoic countenance had become his trademark, a meme now perpetuated in studio publicity.

“Why don’t you ever smile in your comedies?” asked Squier.

“Oh, I don’t know,” he answered. “It’s just my way of working, I guess. I have found—especially on the stage—that when I finish a stunt, I can get a laugh just by standing still and looking at the audience as if I was surprised and slightly hurt to think that they would laugh at me. It always brings a bigger laugh. Fatty Arbuckle gets his humor differently. The people laugh with him. They laugh at me.”

Back in his Arbuckle days, Buster’s expression wasn’t quite so regimented, and he was known to occasionally smile and even laugh. But for Metro he was variously the “frozen-faced comedian,” the “boy with the funeral expression,” and most often simply “sad-faced.” It was an image in the press that perfectly underscored his predicament with Natalie, haplessly hanging around New York, biding his time.

“Peg was still searching the horizon to find a better mate for Natalie,” Anita Loos, who was co-writing Dutch Talmadge’s features, deduced, “but there weren’t even any gigolos around to take up the slack.”

In April, a wire photo circulated in which the couple was seen shopping in New York, Keaton grimly dapper in a three-piece suit, bag in hand. A week later, an item appeared in the “Among the Movies” column of the Nebraska State Journal: “If Buster Keaton did make his trip to New York for the express purpose of marrying Natalie Talmadge he was rather defeated in it, because Natalie now says that she hasn’t enough clothes for a trousseau and he will have to wait until she gets a few more. Latest reports are, then, that Mr. Keaton will stay in New York a while until his lame knee [sic] heals, and then go back to California for a season, returning a few months later to claim his bride. This little misunderstanding as to time and clothes, if such it was, might have been avoided if Buster and Natalie had been carrying on a regular courtship with letters instead of the wordless, letterless, wireless sort.”

By the middle of May, Natalie was promising the press that the marriage would take place within a month and that there would be no elopement. Finally, Keaton could stand it no longer. “We gotta bring this thing to a head,” he insisted.

“Oh, Buster, you know where I’m going.”

“Okay, where and when will we be married?”

“Let’s make it a week from Saturday at my sister’s home.”

But when Buster, still walking with a cane, appeared at the municipal building with Nat, Dutch, and their mother to take out a license, the date had been slipped three days to May 31—which also happened to be the twenty-seventh wedding anniversary of Joe and Myra Keaton. It was a symbolic gesture, likely in consolation since none of the family would be able to attend. The venue was indeed the Bayside home of Norma Talmadge and Joe Schenck, a colonial with six bedrooms and a spectacular view of Little Neck Bay. Playing up the subdued atmosphere of a country wedding, the piazza that afternoon was laden with flowers—snowballs and other late-spring varieties—and the guest list was minimal, just family and a few close friends and co-workers. Dutch Talmadge, who persisted in characterizing the courtship as a “mail-order romance,” was matron of honor for her sister, while Buster’s pal Ward Crane served as best man. In keeping with the easy formality of the occasion, the bride wore a frock of pale gray designed by her sisters, the groom a double-breasted suit and bow tie. Justice Louis A. Valente of the city court officiated.

The wedding of Natalie Talmadge and Buster Keaton at the Joseph Schenck estate on Long Island. From left: Ward Crane, Buster, Natalie, Margaret “Peg” Talmadge, Constance Talmadge, Norma Talmadge (obscured), and City Court Justice Louis A. Valente.

Peg Talmadge, who considered Natalie the “home girl” of the three, made little effort to suppress her melancholy at losing her middle daughter to the West Coast. “It was difficult for me to share Natalie’s assurance that ‘all would be as it had been before,’ ” she wrote in her memoir. “I knew separations were bound to come, though I did not dim her happiness by any such prophecies.”

Apart from empty-nest syndrome, Anita Loos, who attended with husband John Emerson, sensed an element of buyer’s remorse: “Peg’s smile was forced; she considered Natalie’s marriage as a mere substitute for movie stardom. I disagreed. I used to think that looking across a pillow into the fabulous face of Buster Keaton would be a more thrilling destiny than any screen career.”

The Keatons spent their honeymoon en route to Los Angeles, where Buster could mercifully get back to making pictures. He had been away nine weeks, an intolerably long stretch for a man so thoroughly engaged in his work. They stayed with Lou Anger and his wife, singer-actress Sophye Barnard, while Buster searched for a suitable place for them to live. They settled on a relatively modest five-bedroom rental on Westchester Place, less than half a mile from Joe and Myra’s house on Ingraham Street, and stocked their new home with wedding gifts, among them a diamond solitaire Buster gave Natalie, a $2,000 Belgian police dog (Dutch’s contribution), and a fully equipped Rolls-Royce limousine that came from Norma and Joe. Still, the surroundings were considerably less grand than what Natalie had grown used to.

A certain tension between the two was evident from the start. On June 13, the couple attended a benefit baseball game sponsored by the Los Angeles Herald. Shirley Mason, Vi Dana’s sister, had just relinquished her position as guest umpire of the Vernon-Oakland matchup and was looking for a seat. When she saw one and hopped into it, she didn’t realize at first that she was occupying the box immediately next to the Keatons.

“Hello, Buster!” she called. “When did you get back from the wedding trip?”

“Hello, Shirley!” Keaton responded. “Wedding trips mean nothing between friends.” And with that he leaned across the railing and gave her a kiss.

“Bride Natalie was there, looking on at it all,” an eyewitness reported. “She never said a word. But it’s a safe bet that by now Buster knows just what she thought.” The next day, the paper reported that Keaton had returned to the studio on Lillian Way and was once again engaged in the task of making movies.

The time waiting on Natalie Talmadge in New York wasn’t entirely wasted. With Metro’s distribution agreement at an end, Joe Schenck was seeking better terms. And Keaton, like Arbuckle before him, was looking at a case of burnout. “I made eight comedies in the last year,” he had said from his hospital bed. “I intend to make that many next year. And each one has almost a hundred gags in it—just figure that out and see what happens to your imagination at the end of three years. That’s why practically all comedians go sooner or later into five-reel stories with a comedy angle. It’s easier to let someone else worry about the laughs.”

He loved the process of making films, the mechanics and the problem-solving. What he didn’t like was the constant pressure of coming up with fresh, funny ideas. “I string all my stuff together—no, not alone, because everyone in the company helps. But I mean that I’ve never yet bought a scenario, and I’ve had thousands of them offered me. I can’t find funny scenarios. If I could, I’d pay a wonderful price for them.” His solution, at least in the short term, was to make fewer films and use the extra money to properly stage the increasingly intricate gags he envisioned.

Schenck had been in business with Associated First National since 1919, the year they began distributing the Norma Talmadge dramas and her sister Dutch’s feature comedies. They also had a six-picture deal with Charlie Chaplin that was due to expire with the delivery of The Pilgrim in 1922. Originally a circuit of independent exhibitors, First National was in the market for a new series of two-reel comedies, while Schenck was looking to consolidate all his picture interests under a single banner. On May 24, 1921, a week before the marriage that made Buster Keaton his brother-in-law, Schenck entered into a contract with First National for the distribution of six Keaton comedies with an option for another six. Where Metro had reimbursed Comique up to $45,000 per film, First National now guaranteed a flat $70,000 advance, regardless of cost. In return, they would retain all revenues up to $120,000, then split the gross income beyond that figure on a fifty-fifty basis.

The hiatus at the Keaton studio had taken a toll. Jean Havez left to work for Harold Lloyd, leaving Comique with Joe Mitchell as its sole writer. Mitchell, fifty-five, was a good man whose motion picture experience dated back to the Lubin company, where, as an actor, he was reputedly involved in the making of the first film comedy in 1898. As a writer, Mitchell had fashioned a touring vaudeville act for himself and partner Paul Quinn, and co-authored a German soldier sketch for Lou Anger in 1909. Anger elevated him to head writer and went looking to beef up the scenario staff. About the same time, publicist Harry Brand returned to Comique, where he had earlier served as Al St. John’s press agent. Short of staff, Keaton fell back on one of his surest creative instincts, the show business parody.

“During my vaudeville years I never enjoyed anything more than doing burlesques of the other acts on the bill,” he said. “The first I ever tried was one of Houdini getting out of the strait jacket. I was then about six.”

Now that he was making movies, Keaton took aim at one of the industry’s best-known producers, Thomas H. Ince. “Ince,” he said, “started takin’ himself very seriously and his pictures come out saying, ‘Thomas H. Ince presents Dorothy Dalton in Fur Trapping on the Canadian Border. Written by Thomas H. Ince. Directed by Thomas H. Ince. Supervised by Thomas H. Ince, and this is a Thomas H. Ince Production.’ Well, [we’d start] the picture with that, saying ‘This is a Keaton picture. Keaton presents Keaton. Supervised by Keaton….’ ”

It was a wonderful inspiration, but going back to work while his ankle was still mending meant keeping the slapstick to a minimum. “If we can’t have falls and chases, what’s left?” said Jean Havez, presumably as he was walking out the door.

In time, Keaton decided a movie send-up on the order of Moonshine wasn’t viable. “In comedy, like any other kind of picture, you have to do stuff that will be appreciated outside of New York and Chicago. In big cities the people are sophisticated enough to understand travesty and the more subtle bits of humor, but they don’t get over elsewhere.”

Instead, he opted for containing the comedy within the setting of a legitimate theater, effectively minimizing the action while giving himself more opportunities for like-minded gags. “We don’t need falls or chases,” he concluded, envisioning instead a world where every part, every job, every seat was filled by a variation of Buster Keaton. “The whole picture is a visual gag. I hardly have to do anything.”

The development of the untitled picture was augmented by the arrival of a new scenarist, a local newspaperman and magazine writer named Clyde Bruckman. A sportswriter for the Los Angeles Times and later the Examiner, Bruckman had been working for the studios, primarily as a title writer, since 1919. He had also published in The Saturday Evening Post and fancied himself a minor-league Ring Lardner. Bruckman was with Warner Bros., writing for comedian Monty Banks, when he ran into Harry Brand, an old friend from his newspaper days.

“Why don’t you come over with Keaton?” Brand asked.

“How do I know Keaton wants me?” Bruckman responded.

Brand knew; both he and Bruckman had played on an amateur baseball team called the Scribes, and “Bruck” was a terrific pitcher. The next day, Bruckman had a call from Brand inviting him to lunch at the Keaton studio. He went, hit it off with the boss, and was hired on the spot.

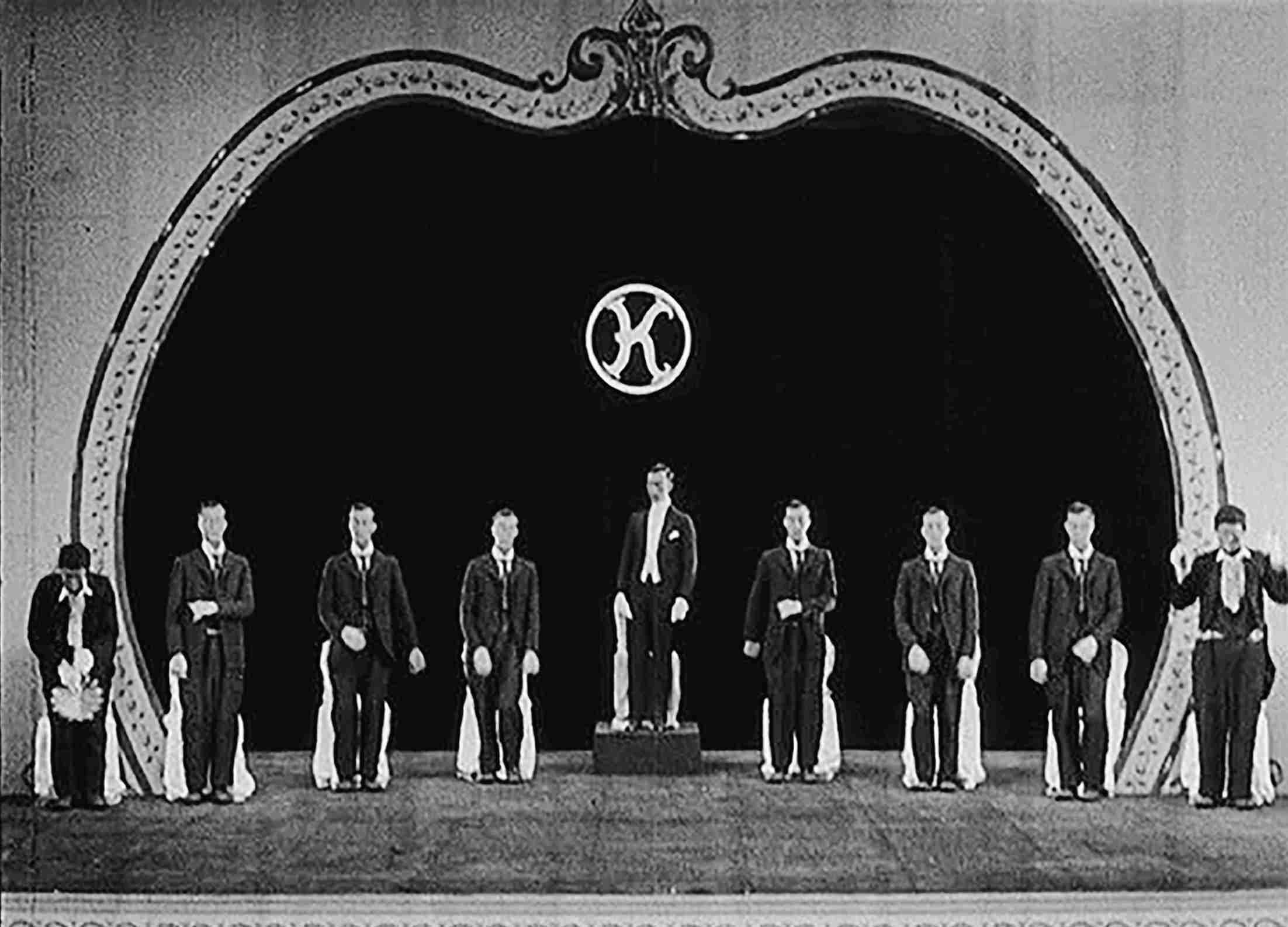

The centerpiece of the new picture was to be a minstrel performance on the stage of an opera house, Keaton figuring he could fit nine images of himself onstage in a single shot. Buster the Interlocutor would occupy the center of the frame, while Buster in blackface would hold down the right and left ends, one as Brother Tambo, whacking the tambourine, the other as Brother Bones, rattling a pair of clappers. Three other Busters would flank Mr. Interlocutor on either side, strutting and playing until the line: “Gentlemen! Be seated.” Envisioning such an ambitious shot was one thing; actually getting it on film was another.

The technique of multiple exposures had been used before, but generally only to show the same actor side by side, playing, for instance, identical twins. At its simplest, this involved masking off half the image, leaving half the frame of film unexposed, then winding it back in the camera and masking off the other half of the image. What Keaton was proposing was to do this nine times over. “Every move, song, and dance exactly in unison,” said Clyde Bruckman, who was present for the filming. “That meant taping off the lens into nine equal segments accurate to the ten-thousandth of an inch.”

Well, not exactly. Shortly before his death in 1955, Bruckman described how Keaton pulled off the effect, building a lightproof box that fitted over the camera, its front comprised of nine equally spaced shutters that could be opened and closed independently of one another, allowing for the exposure of nine different vertical slivers of the frame, rolling the film back in the camera each time. While Bruckman’s description clearly explains the idea behind the effect, silent era camera expert Sam Dodge said it couldn’t have been achieved with a box mounted in front of the lens:

“The camera used to shoot these scenes was a Bell & Howell 2709. They started in 1912 and were the top of the market, the Rolls-Royce camera of their day. The multiple Buster Keaton characters were all done with mattes behind the lens. They could be custom-cut for these scenes, but Bell & Howell made such a huge variety of mattes that there easily could have been mattes that would work for each scene. They required a sharp, hard-edged vignette. Keaton put a lot of pressure on the cameraman to get the mattes positioned just right every time. There were also in-front-of-the-lens mattes in the matte boxes of the time, but they gave a softer edge to the blocked image.”

Making these shots was a tedious process, Buster the sole presence on a crowded stage, working in perfect synchronization with the other exposures. “Actually,” said Keaton, “it was hardest for Elgin Lessley at the camera. He had to roll the film back eight times, then run it through again. He had to hand crank at exactly the same speed, both ways, each time.[*2] Try it sometime. If he were off the slightest fraction, no matter how carefully I timed my movements, the composite action could not have been synchronized. But Elgin was outstanding among all the studios. He was a human metronome.”

An accomplished still picture photographer, Lessley, thirty-eight, had been shooting movies since 1911, initially with the Méliès Star Film Company of Santa Paula, California, later with Keystone, where he brought clarity and depth to a category that didn’t always value such things. He first photographed Roscoe Arbuckle in 1915, and later followed him to Comique. When Arbuckle moved into features, Lessley remained with Keaton, forming a perfect union of technical expertise and comic ambition. Keaton always dictated the setups on important scenes, but gave Lessley his head on incidentals.

The all-Keaton minstrel line from The Play House (1921).

“He would go by the sun,” Keaton said. “He’d say, ‘I like that back cross-light coming in through the trees. There are clouds over there right now, so if we hurry up we can still get them before they disappear.’ So I would say ‘Swell’ and go and direct the scene in front of the cameraman’s setup. We took pains to get good-looking scenery whenever we possibly could, no matter what we were shooting.”

In filming the minstrel show, Keaton left the technical mastery to Lessley while concentrating on the precision of his own movements, which had to be keyed to all the other exposures. There were no retakes—a mistake meant the whole process had to start over from the beginning.

“My synchronizing was gotten by doing the routines to banjo music. Again, I got a human metronome. I memorized the routines very much as they lay out dance steps—each certain action at a certain beat in a certain measure of ‘Darktown Strutters’ Ball.’ Metronome Lessley set the beat, metronome banjo man started tapping his foot, and Lessley started each time with ten feet of blank film as a leader, counting down. ‘Ten, nine, eight,’ and so on. At ‘zero’—we hadn’t thought up ‘blast off’ in those days—banjo went into chorus and I into routine.”

It is a bravura sequence, Buster as ticket buyer, Buster as bandleader, Buster as all six musicians in the pit, Buster as stagehand, Buster as the minstrel line, Buster as the spectators in three different boxes, Buster onstage doing an expertly coordinated dance number with himself—twenty-six individual Busters in all. As technically perfect as it all turned out to be, its effectiveness ultimately rests on Keaton’s extraordinary gifts as an actor. In using posture and attitude to convey character, he is always wry and understated, keeping them all human and never reaching for laughs. First he is a man and his wife, a banker type, stiff and credulous, she impassively fanning herself, slightly bored with it all. He consults his program, which heralds Buster Keaton’s Minstrels—ten cast members and fourteen staff, all Keaton. Scratching his head, he comments to his wife, “This fellow Keaton seems to be the whole show.” In another box, a lollipop-licking boy and his dowdy mother rain candy and soda pop down on the elderly couple beneath them. The old man snores loudly as his haughty wife berates him, mistaking the sticky sucker in her lap for her eyepiece. In what must have been a relief to Lessley, these are all simple two-shots accomplished with a standard matte behind the lens.

Keaton also portrayed various members of the audience in The Play House. “The film has a peculiar aura, not quite like anything else he made,” wrote Penelope Gilliatt. “It is dreamlike and touching, with roots in a singular infancy that he takes for granted.”

In all, it’s six and a half minutes of pure comic genius, beautifully mined for all its satiric potential. Keaton later said he regretted not extending the idea into the rest of the film, saying he made “one very bad mistake” by not doing so. “I could have made the whole two-reeler just by myself, without any trouble. But we were a little scared to do it, because it might have looked as though we were trying to show how versatile I was—that I could make a whole half-hour picture all alone, without another soul in the cast. That’s the reason why we brought other people into the second reel, and that was a mistake.”

At the time, Keaton saw an opportunity to turn the film into a rumination of sorts on the notion of perceived reality, almost as the cinema’s master magician Georges Méliès might have done with the luxury of two reels at his disposal. Awakened from his dream by Joe Roberts as his apparent landlord, Buster’s room is stripped of its furniture and he is ordered out. As he exits, they dismantle the walls to reveal it’s all another stage set, and Buster the stagehand had merely been loafing on the job. Identical twins appear, each seeking a dressing room, Buster just missing the fact that there are two girls and increasingly perplexed by their comings and goings. In the property room, he glances at himself in an old shaving mirror and is startled to see himself multiplied by three. He emerges to find the twins in front of standing mirrors, now suddenly a quartet.

Told to “dress the monkey” ahead of an animal act, he opens the door to the chimp’s cage and unwittingly lets him escape. Seeing no alternative, he blackens himself up with cork, dons evening clothes, and proceeds to channel Peter, the famous “educated chimpanzee” who shared the bill with the Keatons during their ill-fated week at London’s Palace. (“A chimp as a headliner!” Buster exclaimed. “Ever hear of such a thing?”) Peter’s act consisted of taking a formal meal, puffing on a cigarette, doing stunts on roller skates, and driving his own automobile. Keaton mimes the creature with uncanny fidelity, turning on his trainer and climbing the scenery, leaping about the stage in a way that must have made his doctors wince.

A flat comes crashing down, bringing the startled audience to its feet. Buster pilots a bicycle in a figure-eight pattern, then hops through a hole in the backdrop. In the resulting confusion, the Zouave Guards resign and he is left to recruit a crew of ditch diggers to replace them. Under Buster’s command the act is a kaleidoscopic shambles in which the collapse of a scenic wall sends him sliding down the aisle and out the doors of the theater where, in a momentary daze, he purchases a ticket before wobbling back inside.

Having invested the first act with truly extraordinary material, Keaton was faced with the problem of devising a third act strong enough to balance it. While not as visually arresting, the solution was to introduce a young lady, one of the twins, who can “stay underwater longer than the bottom of a river.” Onstage, she dives into a tank of water to demonstrate, only to get her foot caught at the four-minute mark. Buster heroically comes to her rescue, ineffectually at first, then decisively when he retrieves a heavy mallet and shatters the glass. The massive rush of water engulfs the house, sends the spectators fleeing, and blows the theater’s doors off their hinges. Having turned the orchestra pit into a swimming pool, Buster dives in and retrieves the waterlogged girl, then commandeers a bass drum as a vessel and paddles himself off using a violin as an oar.

As a dazzling fantasia of film technique, The Play House, as it came to be known, had no equal in the realm of two-reel comedies. When it played L.A.’s Kinema Theatre in late September, it shared the bill with sister-in-law Constance’s Wedding Bells, and the Keatons were on hand, the house packed. Seated in the club loges, Buster was rigid during the unspooling of his own picture, grim and judgmental amid the gales of laughter. It was only when Dutch’s feature, a clever reworking of a popular stage comedy, came on that he relaxed and permitted himself to enjoy the show. At one point, he laughed out loud and found the people surrounding him were watching him rather than the screen, wondering if such a thing were even possible.

Keaton had fretted that the opening of The Play House left the picture top heavy, and he was right to some degree—nothing could beat that first act. While the Los Angeles Herald unreservedly pronounced it a riot, the verdict in the Times was more measured: “Buster Keaton starts off three laps ahead of everybody in his comedy The Play House, which is billed high, wide, and handsome along with the Talmadge story. Buster tricks you all over the place. You see so many Busters in so many different disguises that you would hardly recognize yourself in the mirror, you feel so dizzy. Finally, however, the star’s little variety show expands into routine comedy—very much routine, and less comedy than usual. The Play House is really somewhat of a comedown for a man who has been climbing steadily.”

In the coverage surrounding the marriage of Natalie Talmadge and Buster Keaton, it was widely reported that the bride would appear with the bridegroom in his next picture. A few weeks later, Nat was embracing the role of homemaker, and Buster had no comment on married life when visited at the studio by a writer from Motion Picture magazine. “It’s too soon yet to say anything,” he told the guy. “I’ve only been married three weeks.” Enigmatically he added: “Marriage is fine as an institution, but bad as a habit.”

Then a July 1 item in the Toledo Blade confirmed by way of night letter the fact that Natalie had “temporally” retired from the screen, having told her mother she was merely giving up a job, not a career. “She is completely wrapped up in her husband and her home, they tell us, and is not spending much time at the studio at present. Maybe later we’ll hear from the youngest [sic] Talmadge sister via the silver sheet—but not now says she.”

A fuller statement of her intentions made the August 1, 1921, edition of the Los Angeles Evening Herald, where it appeared under the byline of Natalie Keaton herself. “I have taken up an experiment costing me $104,000 to determine whether I can become a successful housewife,” she wrote. “In other words, I am turning down an offer of $2,000 weekly in real, honest-to-goodness money which would be paid to me if I appeared in the movies because I want to star in a kitchen role.” She went on to say that when she made up her mind to marry Buster Keaton, she also made up her mind to be the manager of their home. “At present I am looking over Los Angeles and vicinity for a site for that home. I prefer that it be on a high hill. It will be big and roomy. There will be a vegetable garden, a flower garden, a bridle path for horseback riding, and a swimming pool. For years I have been building a ‘castle of dreams’ and this is to be my castle. I will be just an old-fashioned housewife, and plan to make the hours spent in my home the golden hours of my life.”

When Grace Kingsley profiled the couple for the Los Angeles Times, Buster kept quiet and let Nat do most of the talking. She revealed that producer John Golden, a Bayside neighbor, had offered her a part in a Broadway play, but that she chose Buster instead. “I never cared a cent about public life. I always wanted to stay at home.” And she dismissed rumors of other beaux: “Nobody else ever really had a chance for a minute. But I thought I’d keep everybody guessing a bit.” Kingsley described her as sweet-faced, looking “like a little Quaker” with clear brown eyes and a disarming sense of mischief. “Let’s go for a race in my new Mercer!” Nat urged. “I certainly can make that old bus hum!”

In October, Constance Talmadge arrived from New York and invaded the Keaton household on Westchester Place, dragging nine trunks and seven bags of clothing along with her. As the vanguard of a small army of relatives relocating to the West Coast, she entertained questions from the press as Buster showed her around. “Los Angeles is the greatest motion picture center in the world today—always has been and always will be,” she declared, having first come to prominence in D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance, filmed in Hollywood in 1916. “And now we’re all going to be together again in good old Los Angeles, for Norma is coming within six weeks with Joe.” Has Hollywood changed? she was asked. “Yes, I find Hollywood changed. The cellars are now all upstairs.”

Joe Schenck (“the big brother-in-law” as Dutch and Nat referred to him) was moving all his picture operations westward, having leased out the New York studio to Lewis J. Selznick and taken a part interest in the Robert Brunton Studios—soon to be renamed the United Studios—where the Talmadge features were to be made in the future. In April, the Times had reported that Keaton was looking to purchase a studio of his own, but nothing, it appeared, suited him nearly as well as the stage he was already using. The move from Metro to First National, announced in June, forced the issue, and Moving Picture World confirmed Comique’s purchase of the lot—which would officially become known as the Buster Keaton Studio—the following month.

By alternating between two directors, Buster Keaton was able to pass from one film to the next with a minimum of delay. Upon completion of The Play House, he reportedly put Eddie Cline in charge of cutting the picture and began shooting The Village Blacksmith with Mal St. Clair the next day. The new comedy was conceived as a parody of the Longfellow poem, which Buster used to recite onstage. The illustrated title card quoted the first two lines:

“Under a spreading chestnut tree

The village smithy stands;”

Cut to Buster at the base of a California palm tree so tall it takes an extreme long shot to take it all in.

“And the muscles of

his brawny arms

Are strong as

iron bands.”

Buster flexes his arm and a great muscle erupts under the sleeve of his shirt. When it fails to retreat, he jabs it with his tie tack and it bursts like a balloon.

“And children coming

home from school

Look in at the

open door;”

As he works away at the forge and anvil, two schoolboys stop and watch from the street. Joe Roberts, the shop’s owner, comes ambling along, lunch pail in hand, and roughly shoves them aside. Meanwhile, a closer shot reveals that Buster, instead of hammering out horseshoes, is cooking himself breakfast.

The Village Blacksmith was a troubled collaboration, St. Clair preferring a slower tempo than Keaton, and while the film had some clever intervals, such as when Buster acts as shoe salesman to a persnickety horse, there were none of the big ideas audiences had come to expect of him, nor any particularly cinematic ones. “Mal was a great director and eventually became the darling of the New York critics,” said his writing partner Darryl Zanuck, “but he was inarticulate.” When they completed the film in August, Keaton and St. Clair came to an amicable parting of the ways. With a sure sense of visual storytelling, St. Clair would go on to distinguish himself with romantic comedies populated by the likes of Adolphe Menjou, Florence Vidor, and Pola Negri, as well as with the initial film versions of The Show-Off and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

Playing it safe, Keaton returned to familiar territory for his next picture, picking up with his lovestruck couple from One Week, last seen walking off in the distance, the abject ruins of their do-it-yourself house in the foreground. Why not take these two characters, advance the calendar several years, and give them another project to tackle? Sybil Seely had given birth to a son, Jules Furthman, Jr., in March and was available, so Buster gave Virginia Fox the month off, welcomed Sybil back into the fold, and proceeded to create one of his strongest comedies, a fitting companion to the picture that first put him on the map.

The premise for the new two-reeler was even simpler than for One Week. Buster has built a boat in the basement of their house and is intent upon launching it. What follows is a panoply of comic destruction, a celebration of defective reasoning and, as the critic Gilbert Seldes would put it, “intense preoccupation.” In the film’s opening moments, Buster discovers his newly completed craft is too big to fit through a rolling door, so he gets busy with a crowbar and chips away at the brick wall surrounding it. (This gag, he recounted, was inspired by the memory of an actual incident. “The manager of a theater on the old canal at Utica built himself a swell cruiser in the cellar of the theater and had to knock out a side of the theater to get it into the water.”) Deciding he’s done enough, Buster marches over to the Model T, where Sybil and their two sons are waiting, and starts the engine, gingerly dragging the boat by a towline through the still-inadequate opening and making it considerably larger as he does so. And when it finally clears the gaping hole, the entire house, after a splendidly timed beat, collapses in its wake. “The main thing that makes an audience laugh,” he said, “is that something happens to me that could have happened to them. But it didn’t—and they’re glad.”

Perplexed but undeterred, Buster salvages a bathtub and a couple of oars from the rubble and soldiers on. After managing to drive his car off the dock, sending it bubbling to a watery grave, he is ready for a christening. The name on the ill-fated boat is DAMFINO, and like so many things in Keaton’s work, it too can trace its lineage back to his early years, in this case to Muskegon. In 1914, a Chicago-based agent named Eddie Sawyer eased his boat in alongside Joe Roberts’ dock, and the name painted on the bow was DAMFINO (as in answer to the question “Where are we?”). Keaton always relished the name, and may have settled on the idea of a boat picture in order to use it.

Sybil attempts to smash a Coke across the bow, but the bottle holds and all she manages to do is chip the paint. Hanging down from above, her husband produces a hammer and finishes it off. Then, standing aloft, his back to the camera, he gives the signal. Sybil releases the rope tethering the vessel, sending it gracefully sliding stern first down the slipway and into the water, where it smoothly and thoroughly proceeds to disappear below the surface. This simple shot, one of the most surefire laughs in Keaton’s entire body of work, took three days of location time to work out all the bugs. “She simply would not go straight down to the bottom,” he said. And the laugh, he knew, depended on the absolute lack of hesitancy in the DAMFINO’s voyage to the ocean floor.

“We got that boat to slide down the waves. Now, we got something like sixteen hundred pounds of pig iron and T-rails to give it weight. We cut it loose and she slows up, slows up so slow that we can’t use it. Well, you don’t like to undercrank when you’re around water. If you undercrank water, immediately you see it shows, that it’s jumpy. Well, first thing we do is build a breakaway stern to the boat. So when it hits the water it would collapse and act as a scoop, to scoop water. That worked fine, except the nose stayed in the air. We’ve got an air pocket in the nose. We get it back up and bore holes all through the nose and everyplace else that might form an air pocket. Try her again. And there is a certain amount of buoyancy to wood no matter how much you weigh it down. She hesitated before she’d slowly sink. And our gag’s not worth a tinker’s damn if she don’t go straight right down to the bottom. So for a finish, we go out in the bay at Balboa and drop a sea anchor with a cable to the stern, a cable out of a pulley over to a tug out of the shot. We’ve got all of the air holes out of it and the rear end to scoop water—I actually pulled that boat down. That’s the way we got that scene.”

Buster is ready to launch The Boat.

Never was there a thought of abandoning a stubborn gag; good ideas were too precious to waste. “Material was always the number one item for all comics,” Keaton said. “Digging up new gags. We just slept and ate ’em, tryin’ to dig ’em up. The next thing is when you got your gag, photograph it right and do it right. Don’t be careless with it. The other comics around generally were workin’ for somebody on a low budget and if they got the scene halfway they said, ‘That’s it.’ Okay it, and it’s the next setup. It didn’t work with us that way. We spent three days making that gag photograph. Maybe we could afford to—that’s why. But it made a big difference.”

Having handily destroyed both his house and his car, Buster settles into a life of domestic tranquility on the now seaworthy craft, Sybil doing the cooking and cleaning and seeing to the children while he tends to navigation and maintenance. They sail out into open waters, where a storm at sea threatens to scuttle the craft. Buster secures the family belowdecks and radios for help. At the other end of his SOS is Eddie Cline, their sole chance at rescue.

“Who is it?” he wants to know.

“DAMFINO,” comes the reply.

Cline reacts with disgust, as if he’s just been asked if he has Prince Albert in a can. “Neither do I,” he responds, terminating the exchange.

Buster’s backward ingenuity has left two holes in the hull, and now it’s taking on water. He gathers the family up on deck and, using the bathtub as a lifeboat, sets them adrift. Sybil and the boys watch helplessly as he goes down with the ship, where all that’s left of him is his hat floating on the surface of the water. It’s as bleak an ending as a comedy ever had, and Keaton the director lingers on the image before he buoyantly resurfaces and joins the others in the impossibly crowded little tub. Soon, it is taking on water too, and they prepare to drown as a family unit when they discover they’re actually sitting in just two feet of water. Relieved, they stand and slog toward the shore as Sybil asks, “Where are we?” Buster mouths the answer, but an intertitle is unnecessary. And they all walk off into the distance, just as they did the previous year in One Week.

The Boat wrapped in late September with tank work at the Brunton studio. But an event that month cast a cloud over the picture and, at one point, filming was briefly suspended. On September 5, 1921, a party had taken place in a twelfth-floor suite occupied by Roscoe Arbuckle at San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel. Arbuckle wasn’t the host—he was sharing the rooms with director Fred Fishback and actor Lowell Sherman—and people came and went over the course of the afternoon. There was plenty of drinking, and one of the guests, an actress and model named Virginia Rappe, fell ill. The hotel manager and, eventually, the house physician were summoned. Arbuckle described her as hysterical.

“We carried her into another room and put her to bed,” he said. “The doctor and all of us thought it was no more serious than a case of indigestion, and he said a little bicarbonate of soda would probably relieve her.”

Arbuckle returned to Los Angeles the following day.

Roscoe Arbuckle with attorney Frank Dominguez.

It was on September 9 that Arbuckle learned that Rappe had died in a private sanitarium. “I was making a picture,” said Viola Dana, “doing night shots and using Roscoe Arbuckle’s garage and bedroom. At eleven o’clock, Roscoe came in with Sid Grauman and Joe Schenck. Roscoe said, ‘How much longer are you going to be, Vi?’ I said, ‘Not much longer.’ His secretary [Katherine Fitzgerald] was there, and he said, ‘Vi, can you spend the night here with Katherine?’ I said, ‘Yes, I don’t have to work very early tomorrow.’ ‘Fine,’ he said. ‘Now listen, kids. I have to go up to San Francisco. I can’t tell you why. But for God’s sake don’t die on me.’ We thought that was very strange, but we thought no more about it until the next day when we saw the papers. Then, of course, we knew exactly what he meant.”

Upon arriving back in San Francisco in the company of Lou Anger and attorney Frank Dominguez, Arbuckle was arrested and charged with first-degree murder. Details to be placed before a grand jury emerged in the press. Arbuckle, according to a witness, took hold of Rappe, who was Henry Lehrman’s girlfriend, and said, “I have been trying to get you for five years.” He pulled her into an adjacent bedroom and locked the door, and when it was opened sometime later—in answer to repeated pounding by other partygoers and an attempt at breaking it down—Rappe was unconscious on the bed in a disheveled state, her clothing torn, her body bruised. When she came to, and later on her deathbed, she blamed Arbuckle for her injuries, particularly a ruptured bladder, which led to her death from peritonitis. She was thirty years old.

The Arbuckle case immediately became the principal topic of conversation in show business circles. “Nobody is too busy apparently to discuss or listen to the ‘most sensational story ever involving the fourth greatest industry,’ ” Guy Price observed in the Los Angeles Herald. “Not even the divorce and remarriage of Mary Pickford attracted so much general comment. And Charlie Chaplin’s marital faux pas, in comparison, becomes completely obliterated.” In an ominous move, Roscoe’s old friend Sid Grauman ended the world premiere engagement of Gasoline Gus, his latest feature comedy, early on its last day at the Million Dollar, setting off a chain reaction that spread across the country. But even before Arbuckle pictures were being pulled from bills nationwide, attendance figures showed a steep and immediate decline—in some locales by as much as 50 percent.

At the center of the allegations against Arbuckle was a woman called Bambina Maude Delmont, who, as Mme. Delmont, was run off the island of Santa Catalina in 1919 for operating a “beauty parlor” (a slang term for a brothel) at the Avalon dance pavilion. She was also rumored to be a serial extortionist. “She would provide girls for parties,” said stuntman Bob Rose, “and she ran a badger game. She’d get one of these young girls in on a party and have her claim that a producer or director had tried to rape her. Because in those days, they had open house almost. Even tourists would come in on the big Saturday-night parties. So she’d break in on these parties with these girls and try to frame someone.”

Virginia Rappe wasn’t a prostitute, nor had she known Maude Delmont for more than a few days. The connection between them was Al Semnacher, who said he was Rappe’s manager and the man who invited her to join them on a drive north from Los Angeles over the Labor Day weekend. Maude Delmont was soon discredited as an unreliable witness, her testimony blown full of holes at the coroner’s inquest. Yet it was her lurid account the reading public saw first, and it established a widespread impression of the private Arbuckle that proved impossible to dispel. Lacking evidence to support the murder charge, the coroner’s jury found that Rappe nonetheless died from injuries inflicted by Arbuckle and charged him with manslaughter. So while Buster Keaton was busy filming The Boat, Roscoe, held without bail, was languishing in a jail cell some four hundred miles away.

Visibly upset, Keaton called a halt to production the day Arbuckle was arrested, and declined to shoot the following day as well. “We just couldn’t work,” he told Grace Kingsley, fighting back tears. “San Francisco people are doing the whole thing. What right has anybody to condemn a man before he is heard?” Kingsley asked if he was going north to see his old friend. “You bet we are, just as soon as we can find time. We laid off work so long that we’ve got to get busy!” When Frank Dominguez returned to Los Angeles with the express purpose of looking into Delmont’s background, Keaton offered to testify as a character witness, as did other friends of the defendant. “Mr. Dominguez talked us out of going to the trial. He said that there was bitter feeling in San Francisco even against him for taking a case that local people felt should have gone to one of their own lawyers. ‘They would resent you fellows even more,’ he said, ‘and discount your evidence, feeling you were merely Arbuckle’s front men.’ ”

On Sunday, September 18, nearly six thousand people filed past Virginia Rappe’s body at a small funeral parlor on Hollywood Boulevard. A private Episcopalian service held the next day was limited to those who knew the deceased, while a thousand onlookers crowded the street outside. Among the pallbearers that day were director Norman Taurog and the comedians Larry Semon and Oliver “Babe” Hardy. Henry Lehrman, stuck directing a picture in Great Neck, Long Island, sent an elaborate display of lilies dedicated to his “brave sweetheart.”

Dominguez’s investigation led him to believe that Delmont and Semnacher had conspired to blackmail his client, an assertion he put before the court. The following day, the charge of rape was dismissed, leaving involuntary manslaughter as the only count against Arbuckle, enabling him to post bail after nineteen days in stir. To his surprise, the Southern Pacific Depot at Third and Townsend was jammed with well-wishers, mostly women, some bearing flowers. “Arbuckle was not particularly glad to see them,” a man from The New York Times reported. “He smiled and shook hands with them, and thanked them all, accepted the flowers and rolled a brown paper cigarette deftly with his left hand, his right busy shaking hands. There was nothing of the comedian in Arbuckle tonight. The experience he had undergone in San Francisco has chastened him.”

Accompanied by his wife, Minta, and her mother, Arbuckle passed the twelve-hour trip to Los Angeles in seclusion, but was all smiles when he detrained at L.A.’s Central Station sporting a green cap and clad in a dark gray business suit. Fifteen hundred people had turned out to meet him, a repeat of the scene at the San Francisco depot on a larger, more impressive scale. Among those on hand were Eddie Cline, comedian Hank Mann, and exhibitor Mike Gore. Actor Bull Montana broke through the crowd and was the first to offer a hearty greeting. “Thank you, Bull,” Arbuckle was heard to respond as cameras flashed.

Then Keaton extended a hand: “Glad to see you again, Roscoe. You’re looking good. Welcome home.”

He and Lou Anger stayed protectively close as the passengers slowly made their way to a fleet of waiting cars, Roscoe responding to shouted questions from the press with, “Nothing to say,” Frank Dominguez backing him up. Said Minta, “We’re all going right out home—to Roscoe’s house, you know. It’s to be a real homecoming for us all in more ways than one.”

Back at the mansion on West Adams, a party was already in full swing, although Arbuckle, known for one of the best cellars in Hollywood, had taken the pledge. As night fell, the place was ablaze with lights and a steady stream of limousines delivered the famous and the merely wealthy to offer their congratulations. Roscoe smiled his old familiar smile, humbly and sincerely thanked each of them, and rolled countless brown paper cigarettes. Buster, accompanied by Natalie, surveyed the scene: “What could you say to the poor bastard? He was getting the works. A funeral would have been more cheerful. Half the people there whispered and tiptoed around, and the others laughed too loud.”

With Arbuckle safely home for the moment, Keaton launched into preparations for his next First National release, The Paleface. Yet Arbuckle was still being hectored by the authorities. In a lather, Adolph Zukor ordered Frank Dominguez off the case, replacing him with Gavin McNab, probably San Francisco’s best-known attorney. On October 8, Arbuckle was compelled to return to the city, where he was summarily arrested on federal Prohibition charges. Five days after that, he was required yet again, this time for his October 13 arraignment, at which he entered a plea of not guilty. His manslaughter trial was set for November 7, 1921.

Keaton may have settled on an outdoor story like The Paleface because his newly acquired studio was under construction. With only an outdoor stage at his disposal, he was too often at the mercy of the weather, leading to marathon card games in his dressing room when he should have been shooting. Enclosed studios were the norm back in New York, but California had been slow to adapt. When the Brunton lot was designed and built as the Paralta Studios in 1918, five steel-and-glass stages, each large enough to hold five or six sets, were at the center of the layout. As with their open-air counterparts, these indoor stages were intricately rigged with muslin curtains to soften and diffuse the sunlight. But the coming thing on the West Coast were so-called dark stages that blocked out the sun entirely and depended on banks of sizzling arc lights and Cooper Hewitt mercury-vapor tubes for illumination. These did away with the muslin draperies, and to a man like Elgin Lessley, a dark stage held the promise of more creative indoor filming, free of the vicissitudes of natural light. So when applications were made in October 1921 to move the dressing rooms and wardrobe shed to one side of the lot and make room for a new open stage, nearly 150 feet square, allowance was also made for the construction of a dark stage at a projected cost of $50,000.

Shot mostly at the rugged Iverson Ranch in Chatsworth, twenty-five miles northwest of the studio, The Paleface became a watershed for Keaton in that it established a storytelling convention that he would return to frequently. The setup to the film portrayed an Indian land swindle and a murder—heavy stuff for a two-reel comedy. It wouldn’t have worked with most comedians of the day, but Keaton’s natural reserve enabled him to put a stark dramatic opening across that was completely devoid of gags. After ten starring comedies, his pact with the audience was such that they would stay with him as he served up three completely laughless minutes anticipating his entrance.

The opening title:

In the heart of the West,

the Indian of today dwells in

simple peace.

Cut to Joe Roberts as the tribal chief, sitting placidly outside his teepee, puffing on a long calumet.

But there came then a group

of oil sharks to steal their land.

What follows is an executive meeting at the office of the Great Western Oil Company. The president is called away by a ruffian who produces a document. He recounts how he lay in wait outside a government land office for an Indian messenger bearing the lease to their tribal land. The thug creeps up on him and brutally cracks him over the skull, killing him instantly. He steals the coveted paper and presses a coin into the victim’s hand.

“And that’s how I persuaded

him to sell the lease for a dollar!”

The company president returns to his meeting with the paper, and as the others gather around, he begins composing a letter of demand to the chief.

“We’ll give him twenty-four

hours to get off the land.”

When the chief receives Great Western’s notice to vacate, he is outraged and calls a tribal council. “White man kill my messenger,” he announces, gesturing to the fence that marks the boundary of the reservation. “Kill first white man that comes in that gate.” And so a deadly vow of revenge does double duty as the picture’s first surefire laugh. The camera holds on the gate until Buster tentatively peers through, an intrepid lepidopterist with butterfly net in hand.

The Iverson property at the base of the Santa Susana Mountains, with its distinctive sandstone formations suggesting scenes of China, India, Australia, the South Seas, and practically every state of the union, had been serving as a handy filming location since 1912. Keaton seemed to regard it as a wonderland of possibilities for staging memorable stunts and effects, the more spectacular the better. In the ensuing chase, he races down a steep grade, tumbling head over heels to elude the tribe, then is propelled chute-like into a tall tree that abruptly breaks his flight. Collecting himself, he leaps directly into the cluster of Indian braves below, bouncing off them as if by a trampoline and landing safely onto the cliff opposite.

Even more breathtaking is his escape over a steep gully, a rickety suspension bridge offering only a dozen staves and a pair of wires to support him. He manages to cross anyway by placing the loose boards one after another in front of him, only to be met by more Indians on the other side.

“Below the camera line, men were stationed underneath to catch him in case he fell,” observed Ethel Sands, a visitor from Picture-Play, “as there were several sharp rocks which wouldn’t have been particularly soft for even a comedian to fall on. His director [Eddie Cline] enjoyed it immensely—he just roared laughing at Buster, which rather surprised me, as I didn’t think a comedian’s company could get so much fun out of it, but they do apparently.”

Trapped between the two bands of Indians, Buster leaps into the chasm, a climactic stunt that gave even the normally fearless Keaton pause.

“Personally,” he said in a 1930 interview, “I’ve never had the slightest fear of jumping off into a net from a great height, or doing a dive into water, and the only kick I got out of a net jump was during the filming of The Paleface when I had to drop eighty-five feet from a suspension bridge into a net. The day before we shot the scene, the technician who set up the net—and who claimed to be a former fireman—offered to prove the net was safe by making the jump himself. I told him to go ahead. He jumped and, failing to hit the net properly, broke a leg and a shoulder. When I stood in the same spot the next day with the cameras grinding, I couldn’t think of a thing save that man who was in the hospital. I came darn near not doing that scene, but because I didn’t want to show yellow before my own gang, I did the jump and it was successful.”

Returning to Comique after a six-week vacation that took her to Pittsburgh, New York, and Atlantic City, Virginia Fox was assigned the nominal role of the “Indian squab” in The Paleface, making her the only female in the cast. After Buster saves the day for the chief and his tribe, he claims Virginia as his reward, and they end the picture on a dip kiss that, with the aid of one of Clyde Bruckman’s distinctive intertitles, lasts two entire years.

Unusual in depth and scale for a two-reeler, The Paleface would cause Robert Emmet Sherwood, the future Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Idiot’s Delight and Abe Lincoln in Illinois, to hail it as “a veritable epic” in the pages of Life magazine: “It is strange that the silent drama should have reached its highest level in the comic field. Here, and here alone, it is pre-eminent. Nothing that is being produced in literature or in the drama is as funny as a good Chaplin or Keaton comedy. The efforts of these young men approximate art more closely than anything else that the movies have offered. They are slapstick, they are crude, they are indelicate to be sure, but so was Aristophanes, so was Rabelais, so was Shakespeare. How many humorists who have outlived their own generations have been otherwise?”

With the release of The Play House on September 19, 1921, First National took ownership in a big way. “Keaton Is Ours!” crowed a display ad in Variety. “No longer a prospect—Now a gold mine!” Mindful of exhibitors who had loyally booked the Keaton comedies when Metro had them, the new distributor announced it was making its two-reelers available to theaters on the open market, not just to First National franchisees. “They will be in two groups of three each. You can contract for the first three as a series or each release separately. Nothing funnier made! Get busy!” A three-page display touting the entire fall lineup followed in Exhibitors Herald. Featured up front alongside The Play House was Chaplin’s The Idle Class, set for an October release. Also from First National: Pola Negri in One Arabian Night, Richard Barthelmess in Tol’ble David, Norma Talmadge in The Sign on the Door, Constance Talmadge in Woman’s Place, new releases from directors Raoul Walsh and John M. Stahl, and Marshall Neilan’s Bits of Life.

First National’s superior reach was apparent from the outset. Metro released The Goat, its eighth and final Keaton subject, on October 15 and achieved worldwide rentals of $101,041, a figure on par with its other Keaton pictures, while the corresponding “played and paid” number for The Play House, put out by First National a month earlier, was $155,286—a jump of more than 50 percent. The Boat, at a cost of $22,000, posted similar results when it was released on November 28. With the first series of three completed, Keaton embarked on the second series of releases with what was to become the best known and most celebrated of all his short comedies, Cops.

As with The Paleface, the making of Cops coincided with the construction of the dark stage on the Keaton lot, encouraging a story line that required no interiors. And, as was always the case with Keaton, the simplest concept yielded the best results. “You could write the whole plot on a postcard,” he said. “We do the rest.” What he envisioned was a pursuit through the streets of Los Angeles “just ducking cops in all directions. Just a common ordinary chase sequence.” But it would all lead up to a powerful finish in which Buster was chased en masse by the city’s entire police force. “Three hundred and fifty [cops],” he said in a 1963 interview. “And it was because we could only find three hundred and fifty cop uniforms.”

The logistics of such a shoot required pre-planning on a scale Keaton and his production team had never before attempted. Every gambit, every evasion had to be thought through in advance. Locations had to be selected, extras scheduled and costumed. No picking up a quick shot a block from the studio—too many moving parts to coordinate. He was always proud of the fact that he never worked from a script, but the paperwork needed to make Cops must have come awfully close to one. Even so, his organic method of working gave him plenty of leeway.

“The director, a couple of scenario writers, and I sit around and discuss a scene. That is how the gags are made. Then we shoot the scene. Lots of things develop during the actual taking of the picture which we hadn’t thought out at all.” The matter of rehearsal was anathema to him. “For any of our big rough-house scenes where there is a lot of falls and people hitting each other, we never rehearsed those. We only just sat down and talked about it. [I’d say], ‘Now he drops that chair, you come through the door and come through fast, and this person here sees you come and throws up their hands and from the center door you can see it. Now you come through and just about hit him. If you miss, get her.’ ” Then they’d walk through it to get the timing. “If you had to do it a second time, invariably somebody skinned up an elbow or bumped a knee or something like that, and now they will shy away from it the next take, or they will favor it. See, you seldom got a scene like that as good the second time. You generally got them that first one, and anybody in that scene is free to do as he pleases as long as he keeps that action going. So, even your extras can use their imagination.”

In Cops, the action is set in motion by Virginia’s rejection of him as a suitor. “I won’t marry you,” she tells him, “until you become a big business man.” Thus motivated, Buster resolves to prove himself a wheeler-dealer. He is tricked into buying a wagonload of furniture drawn by a downtrodden horse named Onyx. (Clyde Bruckman bestowed the name because the animal purchased for the role was a bedraggled white in color.) Onyx is singularly lacking in energy, and Buster’s efforts to urge the horse along have no discernible effect. Finally, he takes the bit in his mouth—literally—and starts pulling the wagon alongside the horse.

“We planned it to lead into another gag,” Buster remembered. “We wanted to pan the angle shot slowly from me and on to show Onyx riding in the wagon and then to the furniture all unloaded and piled in the street. For two days we tried to get Onyx up into the wagon but he wanted no part of it. He wouldn’t walk up a ramp, refused to be hoisted in a veterinary’s belly band, kicked whenever we came near. Saturday we passed up the baseball game to work on the problem. But no soap. That night we quit, tired and disgusted. Monday morning we saw the reason for it all—a brand new colt standing wobbly alongside of her. Her I said. What a bunch of dopes we were.”[*3]

It’s the day of the city’s annual police parade. Bruckman’s title:

Once a year, the

citizens of every city

know where they can

find a policeman.

Coming upon the vast sea of marching blue uniforms are Buster, Onyx, and the loaded wagon of furniture. All that was left to do was to spark a pursuit. “I tried to cut through the parade and I couldn’t do it, so I just joined it. And before anybody could stop me, some anarchist up on top of a building threw a bomb down on the police parade, but it lit in my wagon. So when it went off, the whole police force was after me.”

Instantly, Buster has hundreds of cops on his tail. Onyx breaks into a gallop, the viewing stands clear out, and a hydrant is sheared off, sending a geyser of water skyward. The old wagon collapses, and they’re all upon it, but the suspect is nowhere to be found. When he appears under an open umbrella, the cops give chase, swarming everywhere. Charging bands converge on a street corner, smoothly snaking past each other while Buster hides inches away. Everywhere they go, he outruns them. Emerging from a Hollywood alleyway and onto a busy street, he grabs on to a passing car and neatly whisks himself away. Was the car going that fast? Keaton was asked during a TV interview. “No,” he replied, “that’s undercranked a little bit—but not much. The actual speed, I guess you could say…Well, when a man runs one hundred yards in ten flat, you know what his actual speed is? Nineteen miles an hour. That car’s only going about fourteen ’cause you couldn’t take it that fast. Take your arm right out of your socket. Couldn’t take it.”

Two cops approach from opposite directions, their batons raised. Buster dashes between them, and they knock each other out cold. At a construction site, he climbs a ladder that teeters on the top of a fence, a cop at one end, he at the other. Soon reinforcements arrive and converge in full force. Buster ducks into the Fifth Precinct Police Station and they follow him in, packing the building until the walls nearly bulge. He emerges in uniform, completely unnoticed, and closes and locks the doors. Just then Virginia, the mayor’s daughter, comes along and rejects him for the spectacle he’s made of himself. As she walks away, he unlocks the doors and allows himself to be pulled inside. To suggest the darkest of outcomes, the THE END card is illustrated on a tombstone, Buster’s pork pie hat, cocked at a saucy angle, resting atop it.

An entire municipal police force gives chase in Cops (1922). “This chase sequence—how much of it was planned way in the beginning and how much came out in the actual doing?” Studs Terkel asked. “Well,” said Keaton, “as a rule, oh about fifty percent you have in your mind before you start the picture, and the rest you develop as you’re making it.”

The filming of Cops stretched over a large swath of the city, adroitly taking advantage of actual streetscapes as well as the standing sets at several different studios. “That poor horse filmed at nine different spots all around L.A. and Hollywood,” said renowned location historian John Bengtson, who has identified every scene in the picture, “and at the Goldwyn, Metro, and United backlots.” That the completed film is so seamless in its jumps from setting to setting is a testament to Buster Keaton and the expert team he and Lou Anger had assembled at the Keaton studio.

There was now a general feeling among critics that Buster Keaton, with his new series of comedies for First National, had risen to the same level of artistry as Charlie Chaplin, creating a body of work unparalleled in the world of film. “Keaton,” declared The New York Times, “is one of the few really accomplished clowns of the screen, constitutionally comic, it seems, and never more so than in The Play House.” Notices celebrated his magical use of the camera, and the word “unique” popped up with striking frequency. “The most unique and original comedian,” said The Milwaukee Journal. “An amazing bit of double photography seen in this picture. There’s a whiff of love interest and plenty of comedy. You ought to see this picture. It’s so unique it’s uncanny.” The Atlanta Journal also invoked the word, calling The Play House photographically unique: “Keaton has never made a comedy with more ingenious contrivances to amaze the audience. Neither has any other film comedian.”

In New York, The Boat was similarly praised by the World ’s Heywood Broun, who singled it out on a bill at the Rivoli, where the main attraction, UFA’s Mistress of the World: The Dragon’s Claw, was given relatively short shrift. “The feature film is magnificent,” Broun said of the epic German production, “but it has neither the ingenuity nor the imagination of the Keaton comedy. Peculiarly enough, few so-called serious pictures of home manufacture employ processes of thought to any extent. It is only the business of being funny which sets producers and actors to thinking. Keaton is an exceedingly agreeable performer, and the material that has been devised for his talents in The Boat is altogether exceptional.

“Much has been done already on the screen in the development of trick automobiles which explode at convenient moments, and farcical aeroplanes and disorderly submarines, but nothing within our experience has equaled the antics of Keaton’s yawl. From the moment of its launching, when it slides down the ways to sink nose first with a preliminary gurgle and a few bubbles, the little yacht achieves an altogether fascinating irrationality. Through this comedy we move like merry dream people, as Keaton’s yacht cruises its sharp course in spite of bridges, docks, and all respectable inanity which is reared against it. Our own feeling of self-sufficiency was vastly stimulated by the scene in which Keaton and his crew sank in the middle of the Pacific only to step out and find that the water came no higher than their knees. The catastrophe occurs at night, and the picture leaves the characters standing wandering upon some dark and dry land set at an unknown spot in an elemental wilderness.

“In this,” Broun concluded, “there is poetry.”