10

Our Hospitality

WITH THE BALLOONATIC cut and titled and his First National commitment at an end, Buster Keaton took his young family to New York for an eight-week respite, the entourage including Lou and Sophye Anger, Eddie Cline and his wife, and publicist Harry Brand. It was common to see Hollywood types stalking Broadway in the autumn, scouting material and catching up with old friends. When the Keatons arrived on the Main Stem, celebrities from the West included one of the Gish sisters, actress Hope Hampton, and actors Huntley Gordon, Montagu Love, and Richard Barthelmess. Joe Schenck, meanwhile, was off touring his native Russia with Norma, Dutch, and Peg Talmadge, and the plan was for the Keatons to remain east long enough to meet their ship.

The Frozen North had gone into release in mid-August, making it the first movie copyrighted in the name of Buster Keaton Productions. “A good time for a snow picture,” Keaton commented. “Air conditioning wasn’t invented yet.” The Electric House followed in October. While in Manhattan, Keaton would see Cops featured top-line at the Symphony Theater on the Upper West Side, while My Wife’s Relations was similarly billed on its initial run at the Rivoli.

“The best of the three is My Wife’s Relations,” Robert Sherwood opined, “but The Electric House and The Frozen North are not far behind. They are all genuinely funny, with occasional thrusts of satire—and they are full of that amazing ingenuity which is a characteristic of every Keaton comedy. Buster Keaton is a distinct asset to the movies. He can attract people who would never think of going to a picture palace to see anyone else. Moreover, he can impress a weary world with the vitally important fact that life, after all, is a foolishly inconsequential affair.”

Keaton also sat for interviews. Stifling a yawn during a session with the Telegraph’s Gertrude Chase, he was asked about New York nightlife. “Terrible,” he answered. “I haven’t missed a night at the theatre. Then there are the races, and now the World Series. No wonder I’m underweight. We are seeing as many plays as we can with a view toward getting a new picture for Constance. The one I would like to see her do is Kiki, but it may be hard to get.”[*1]

When Chase asked if she could see the baby, now four months old, she was told he was airing on Park Avenue and that she could find him when she went out. “You can’t miss him,” the proud father said. “He looks just like me. He has a black buggy and a white nurse.”

Keaton had now starred in nineteen short comedies, three of which were yet to be seen by the moviegoing public. “Next I’m going back to the coast to do a five-reel picture,” he told Malcolm Oettinger, who was doing a new piece for Picture-Play. “No plots, you know. Just gags. But we’ll space our laughs. If we ran five reels of the sort of stuff we cram into two, the audience would be tired before it was half over. So we’ll plant the characters more slowly, use introductory bits, and all that. It’ll be just as easy to make a five-reeler, because we always take about fifteen reels anyway. Now we’ll cut to five instead of two.”

Schenck and his party concluded their tour of Russia, which included a pilgrimage to Joe’s birthplace on the Sheksna River, in early November. They arrived in Paris on November 6, 1922, and moved on to England a few days later. The order of business there was the judging of a nationwide beauty contest conducted in the pages of The Daily Sketch, which drew eighty thousand entries. Of all the photo submissions, one hundred finalists were brought to London to attend a luncheon with the Talmadge sisters at the Savoy Hotel, followed by participation in the fifth Victory Ball (commemorating the end of the Great War) and the making of individual screen tests at the Stoll Film Studios at Cricklewood. The reward for the lucky winner was to be the role of Aggie Lynch, the second female lead in Norma’s next picture, Within the Law.

In terms of publicity, the campaign was wildly successful, with the newsreel Topical Budget (under the same ownership as the Sketch) filming contestants in twenty-one regional districts. Norma, Joe, Dutch, scattered First National executives, and members of a Grand Committee of British notables spent hours in an Oxford Street cinema watching the tests and winnowing the entrants until, after much back-and-forth, they finally had a winner. On November 14, the Sketch carried a front-page photo of Irish-born Margaret Leahy, who had beaten out all other contenders. Norma pronounced the twenty-year-old shopgirl “a perfect film face” with “splendid eyes, a supple body, and convincing expressiveness…her features are so perfect and her character so distinctive!”

Following a quick victory lap, which included the premiere of Constance Talmadge’s East Is West and a tour of the provinces, Leahy and her mother boarded the Aquitania with Schenck and the Talmadges for the long journey to Hollywood where, as The Daily Sketch girl, she would surely attain stardom. Buster, Nat, little Joe, and the Angers were among those at the Cunard dock to welcome them when they arrived on December 1, and four furious days of sightseeing and camera tests ensued. “She is of the petite, chic type,” inventoried The New York Times, “with chestnut hair, blue eyes, and white even teeth and natural pink complexion.”

Also meeting the ship that day was Within the Law director Frank Lloyd, who would be making authentic exteriors with Norma before accompanying the group home by rail. It was during this brief period that Lloyd got his first look at how Leahy comported herself in front of a camera, and he feared she had little to offer the screen. That fear only magnified when they got to Los Angeles and production on the Metro lot began in earnest. In a diary entry published in the Sketch, Leahy described doing a scene for Lloyd fifteen times. “They have taken thousands and thousands of feet of film of me,” she wrote. “Mr. Lloyd says he is very proud of me.”

Nevertheless, three days in, Lloyd abandoned all hope of coaxing a performance out of her. The girl couldn’t act, he concluded. She was hopeless. Norma, the public face of the stunt, was too invested to send her home. Yet Lloyd was adamant and she knew he was right. Joe mustered all the diplomatic skills at his command and told Leahy he had decided he would not be treating her fairly by putting her into a big part without any training, one that would likely expose any “camera faults” she might have. Rather, he said he was extending her contract so that she could watch Lloyd develop Within the Law from a directorial angle without the pressure of actually having to appear in it.

“Margaret Leahy has natural ability, is ambitious and beautiful,” he said in a statement to the press. “Consequently, if properly handled, she will win fame in pictures. I am determined that she shall have every opportunity at my command to be successful, and for that reason I have decided that she shall be educated for the screen before actually being photographed.”

This solved the immediate problem of getting the picture back on track, and the role of Aggie Lynch was hastily recast with the well-established Eileen Percy. Leahy, at least publicly, pronounced herself satisfied. “I realize that stars are not made through popularity contests, but through hard work, perseverance, and experience,” she said.

The matter of Roscoe Arbuckle was far from settled. In July it was rumored he would return to the stage—where the ban initiated by Will Hays had no effect—but nothing emerged from reputedly “secret” negotiations. In August, with no prospects, he sailed from San Francisco on a voyage to the Orient. It was the first leg of a long trip that would take him to the Malay Peninsula, the Straits settlements, Egypt, and possibly Paris.

“I need a rest and intend to take it easy and, at the same time, see some other parts of the world,” he told the Oakland Tribune. “I’ll come back to the United States in due time, and then will be my opportunity to decide what I’m going to do. It’s entirely up to the people—the people who see the movies and who used to be (and, I think, again will be) my friends—whether I return to the screen or not. Maybe I’ll go back to making comedies, but I don’t know. San Francisco doesn’t make me feel very funny and I can’t say right now. Maybe I’ll go into the business as a producer.”

It was thought that Arbuckle would meet up with Joe and Norma in Egypt, but he suffered an injury on the initial voyage—sliced open a finger after slipping on some steps—and never made it farther than Japan. In October, the trades reported a $400,000 cash offer made by Gavin McNab for the three unreleased Fatty Arbuckle features produced and then shelved by Famous Players. The attorney also indicated that he had access to “practically unlimited” amounts of money from Chicago, New York, and other eastern investors to finance a comeback.

“This money is seeking investment in Arbuckle as a result of a most thorough sounding out of public opinion throughout the United States, with the result that a practically unanimous sentiment favoring his return to film work has been encountered.” He added that he felt sure the Hays banishment, which was always characterized as temporary, would be lifted once a personal appeal had been initiated by Arbuckle and his attorney. Nothing, though, ever came of the plan.

In December, The Film Daily reported that Arbuckle’s friends would make a concerted effort to persuade Hays to let the man work again. How much of an effort got made is unknown, but on December 21, 1922, Hays announced that he saw no reason why Arbuckle should not be permitted to go back to work if he wished to do so. Hays later said it seemed “a relatively commonplace decision to me,” but a tsunami of public indignation immediately engulfed him, beginning with the Los Angeles District of the California Federation of Women’s Clubs, which, representing a membership of two million, reaffirmed its opposition to Arbuckle’s returning to pictures. The mayors of Indianapolis, Detroit, and Boston quickly said they would not permit his comedies to be shown in their cities, and similar statements of disapproval came from the National Catholic Welfare Council, the National Education Association, and club women and religious leaders in Chicago, Philadelphia, St. Louis, Buffalo, and Milwaukee.

All the righteous civic and clerical noise prompted Arbuckle to issue a plea for “American fair play” on Christmas Eve. “It is not difficult,” he said in the statement, “to visualize at this time of year, which commemorates the birth of Christ, what might have happened if some of those who heartlessly denounce me had been present when the Savior forgave the penitent thief on the cross with words that have influenced the human race more than any other words ever uttered. Would not some of these persons have denounced Christ and stoned him for what he said? No one ever saw a picture of mine that was not clean and wholesome. No one ever will see such a picture. I claim the right of work and service. The sentiment of every church on Christmas Day will be ‘Peace on earth and good will to all mankind.’ What will be the attitude the day after Christmas to me?”

When the Keatons returned to Los Angeles, Buster grimly watched as the Talmadge women once again made the house at Westmoreland Place a hive of activity. Even though Norma and Dutch were both making pictures at the nearby Metro studios, the baby, now six months, was an endless source of fascination and brought a steady stream of visitors. “It was not exactly a rest home,” Buster conceded. Keen on downsizing—the third floor at Westmoreland was a ballroom where Dutch had learned to ride a bicycle—and eager to own, the Keatons found an eleven-room residence on Ardmore Avenue in the fashionable Normandie Hill tract, a “big tile-roof deal with lawns and clipped yews” for $50,000 with a $35,000 mortgage held in the name of Natalie’s mother. By year’s end, Nat was planning the move while Buster was preparing to put his first feature comedy before the cameras.

At work on the feature comedy that would come to be known as Three Ages (1923). From left: Joe Mitchell, Clyde Bruckman, Keaton, Jean Havez, and Eddie Cline.

In some ways, Three Ages was a feature in name only. Keaton, who said he had D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance in mind, described the concept in a 1958 interview: “What I did was just tell a single story of two fellows calling on a girl, and the mother likes one suitor and the father likes the other one. And in fighting over the girl and different situations we could get into. And finally winning her. But I told the story in three ages. I told it in the Stone Age, Roman Age, and Modern. In other words, I just show us calling on the girl, the two of us gettin’ sore at each other because we were in each other’s way. Then I went from the Stone Age to the Roman Age, did the same exact scene with the same people, only the setting was different and the costumes. And the same thing in the Modern Age. So every situation we just repeated in the three different ages.”

Griffith’s picture was comprised of four interwoven stories, set in four different ages, exploring the theme of intolerance—social, religious, political. When the film failed at the box office, he was able to edit the Babylonian footage into a stand-alone feature called The Fall of Babylon, and similarly repurpose elements of the Modern Age story as The Mother and the Law—a shrewd commercial resurrection not lost on Keaton.

“Cut the film apart,” Keaton said of Three Ages, “and then splice up the three periods, each one separately, and you will have three complete two-reel films.”

Indeed, Buster was leaving nothing to chance. Not only would he hedge his bets with a modular structure, he would also beef up his two-man writing staff. Accompanying him back to Hollywood was Tommy Gray, having signed on for another tour of duty. Awaiting their arrival was Jean Havez, fresh from a year’s sojourn with Harold Lloyd. Added to Mitchell, Bruckman, and Cline, Keaton assured himself of what the Los Angeles Times termed “the largest scenario department of any individual star.” To play his rival for the love of the girl Keaton selected Wallace Beery, a roughneck character man who had a background in comedy, and for the girl’s imposing father he borrowed Joe Roberts back from Fox, where he had appeared in films for directors Slim Summerville and Norman Taurog.

Unsettled until late in the game was the matter of a leading lady. “The cast for our two-reelers was always small,” Keaton said in his autobiography. “There were usually but three principals—the villain, myself, and the girl, and she was never important. She was there so the villain and I would have something to fight about. The leading lady had to be fairly good looking, and it helped some if she had a little acting ability. As far as I was concerned, I didn’t insist that she have a sense of humor. There was always the danger that such a girl would laugh at a gag in the middle of a scene, which meant ruining it and having to remake it.”

Joe Schenck never involved himself in the creative side of Keaton’s pictures. “Tell me from nothing,” he would say. “Go ahead, what should I know about comedy?” But still needing a feature role for Leahy, Schenck saw an easy out in putting her with Buster. It didn’t matter that she couldn’t act; Keaton would be helping both Norma and him out of a jam. When it was all settled and arranged, Schenck personally phoned Leahy with the news, laying it on thick. They were entrusting her, he said, with the biggest prize of the year—the lead in the Buster Keaton super-production that all the film fans in America were eagerly awaiting. “I am going to show England what we think of its Daily Sketch girl,” he declared.

On January 7, 1923, a two-column item appeared in the Los Angeles Times announcing the switch in casting: “Miss Leahy was originally chosen for the role of Aggie Lynch in Within the Law, but after a week spent in the taking of tests it was agreed that she possessed the talents so necessary for an ingénue and she was chosen to play the important role of Buster Keaton’s lead, a part more important than the one for which she was selected as the winner of the beauty contest.” Production, it said, would get under way “within another week.”

When Roscoe Arbuckle moved from shorts to features in 1920, specifically comedy-dramas like The Round-up, Grace Kingsley of the Los Angeles Times asked him why. “It’s just about a hundred times easier to make a comedy-drama than a two-reeler,” he replied, “and you get more for it. Also you get more fame. People go in and laugh when they see you in a jazz comedy, but all the same they think to themselves, ‘Pooh, that’s nothing! He’s just a boob.’ Yet you have worked yourself sick and your brain is fagged thinking up new gags for that comedy.”

Keaton had wanted to move directly into features after his apprenticeship with Arbuckle, but Joe Schenck was against the idea, probably feeling that Buster needed to carry some pictures on his own first. In the interim, both Chaplin and Harold Lloyd made the switch, Chaplin with The Kid, a six-reel subject that made a star out of Jack Coogan’s six-year-old son, and Lloyd, unofficially, with A Sailor-Made Man, a two-reel picture that blossomed into four, and then officially with Grandma’s Boy.

“We didn’t get William S. Hart, Mary Pickford, or Douglas Fairbanks on the same bill with us,” Buster said. “We had second- and third-rate stars on the bill with us. Well, for instance, if the theater, a first-run theater here in Los Angeles, was paying us $500 a week rental for our short, he was probably paying only $500 for the feature….As long as they were going to advertise us above it anyhow—we’re the drawing card—we might as well get into the feature field and instead of getting $500 for the picture we take $1,500. It makes a difference.”

Creatively, he echoed Arbuckle’s reasoning in that he had grown to want longer stories and the room to develop them. “We were knocking ourselves out dreaming up new stuff every six weeks—and gambling each time. A couple of duds in a row and you could slip way down the ladder. With six months—four times as long—to each film, you could give it all you had.”

Work on Three Ages began in January 1923. Judging from the diary entries Leahy filed with The Daily Sketch, Keaton began by puzzling out the Modern Age story, which would then serve as the basis for the Stone Age and Roman segments to come. “It is only preliminary work that we have done so far,” she wrote. “Mr. Keaton is not quite sure yet about several points in the picture. It is to be a super comedy, and several of the scenes and incidents are tried out before they are actually taken—that is, we do certain scenes two or three ways before the camera, then we see them run off in the little projection room, and Mr. Keaton finds things wrong with them or gets better ideas, and then we do them over again. When these difficult points are cleared up we will start again, and work the picture right through. There is a scene in which there is a fire—a whole house seems to be burned down, and we have burned it down three times now, and still Mr. Keaton is not satisfied. Of course they do not really burn down an entire house. They build just the front of it. They build it at night, working all night, and then we burn it down in the day time. Mr. Keaton says if he can’t get the house to burn down properly he will cut it out of the picture after all.”

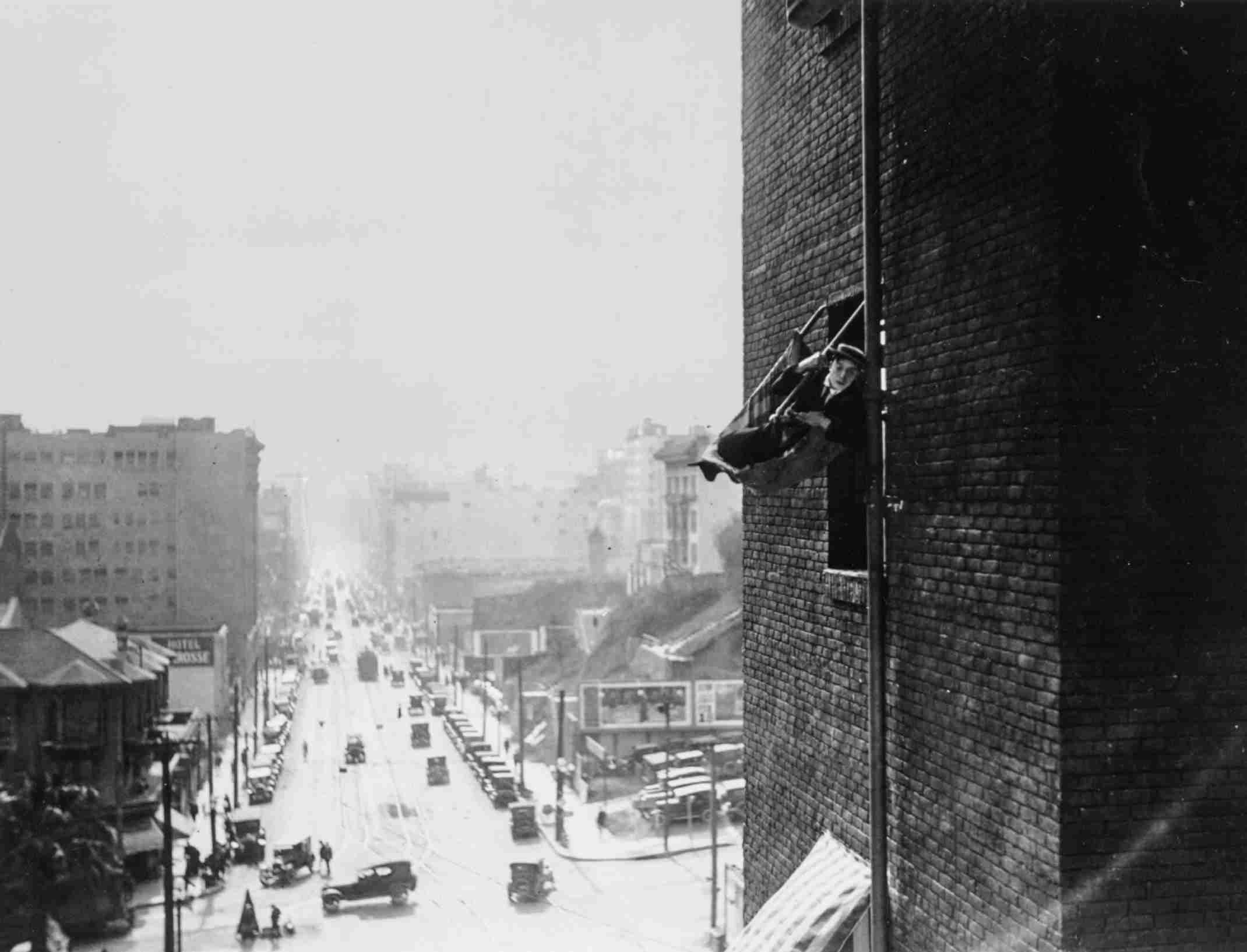

There was indeed a fire in the conclusion to the modern story, but it engulfed a police station rather than a house. Buster initiates an escape from the cops, desperate to stop Leahy’s reluctant marriage to Beery. Climbing a fire escape to the top of a tall building, he must leap from one roof to the next to clear an alleyway.

“We built the sets over the Third Street tunnel—or the Broadway tunnel—looking right down over Los Angeles,” Keaton remembered. “Now, by getting your cameras up on a high parallel and shooting past our set in the foreground with the street below, it looked like we were up in the air about twelve, fourteen stories high. And we actually had a net stretched from one wall to the other underneath the camera line so in case you missed any trick that you were doing—one of those high, dizzy things—you had a net to fall into, although it was about a thirty-five-foot drop….So, my scene was that with the cops chasing me, that I came to this thing and I took advantage of the lid of a skylight and laid it over the edge of the roof to use as a springboard. I backed up, hit it, and tried to make it to the other side, which was probably about eighteen feet, something like that.

“Well, I misjudged the spring of that board and didn’t make it. I hit flat up against the other set and fell to the net, but I hit hard enough that I jammed my knees a little bit, and hips and elbows, ’cause I hit flush, flat. And I had to go home and stay in bed for about three days. And, of course, at the same time, me and the scenario department were a little sick because we can’t make that leap. That throws the whole chase sequence, that routine, right out the window. So the boys the next day went into the projecting room and saw the scene anyhow, ’cause they had it printed to look at it. Well, they got a thrill out of it, so they came back and told me about it. ‘It’s a miss.’ Sez [I], ‘Well, if it looks that good let’s see if we can pick it up this way: The best thing to do is to put an awning on a window, just a little small awning, just enough to break my fall.’ ’Cause on the screen you could see that I fell about, oh I guess I fell about sixteen feet, something like that. I must have passed two stories. So now you go in and drop into something just to slow me up, to break my fall, and I can swing from that onto a rainspout, and when I get a hold of it, it breaks and lets me sway—sways me out away from the building hanging onto it. And for a finish, it collapses enough that it hinges and throws me down through a window a couple of floors below.

A breathtaking aerial stunt salvages a missed leap from rooftop to rooftop in Three Ages. This exterior set was constructed atop the double-bore Hill Street tunnel in downtown Los Angeles to create the illusion of great height.

“Well, when we got back and checked up on what this chase was about, the chase was this: I was getting away from policemen and we used the old Hollywood station, which was right next door to the fire department. Well, when this pipe broke and threw me through the window, we went in there and built the sleeping quarters of the fire department with a sliding pole in the background. So I came through their window on my back, slid across the floor, and I lit up against the sliding pole and dropped to the bottom on the slide. I bounced from that to sit on the rear of one of the trucks, and as I hit the rear, the truck pulled out. So I had to grab on for dear life, but I’m on my way to a fire—but the fire was in the police department. So we went back and shot the scene where I accidently, not knowing it, had set fire to the police department before the cops started to chase me. Well, it ended up…It was the biggest laughing sequence in the picture…because I missed it in the original trick.”

Keaton shot the entirety of the Modern Age story as if filming a two-reel comedy, and it was that material that formed the backbone of the picture.

“Working with Buster Keaton one has to keep one’s wits,” wrote Margaret Leahy. “We rehearse a scene and then the director calls, ‘All ready. On the set…Shoot!’ Then we start the scene just as we have rehearsed it. But Mr. Keaton may have a sudden idea right in the midst of the scene and will start doing something entirely different from what we had rehearsed. If I can ‘follow’ him, or understand instantly what he is doing and what I should do—then everything is all right. But if I am surprised the least bit and ‘caught napping,’ then the scene is spoiled. The director shouts ‘Off’ and the camera stops and we start over again.

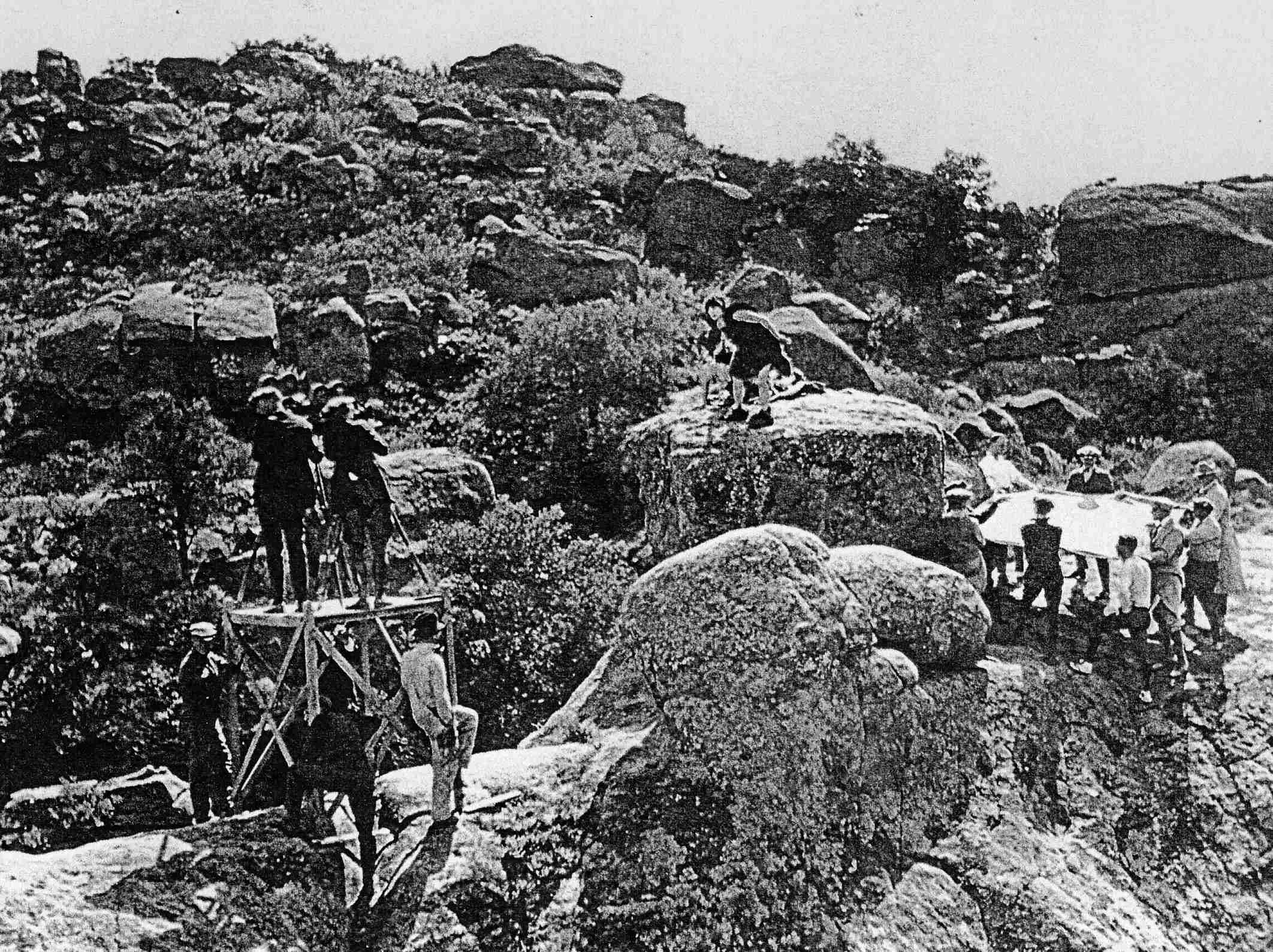

Keaton prepares to film a scene for Three Ages at the Iverson Ranch in Chatsworth. To the right are men poised to catch him with a tarp after he sustains a whack from actress Blanche Payson’s club.

“I went through one whole day splendidly. Mr. Keaton changed every scene right in the middle of it. For example, in one scene we had rehearsed for him to go slowly out of the door, hat in hand, and turn at the door to wave good-bye to me. I was to stand very straight and solemn—angry with him and indignant. Not noticing him at all as he left. Then, just as he pushed up his hat and started to go out of the door he changed his mind. He threw his hat down and came over to me and grabbed me in his arms and kissed me. I hadn’t the least idea he was going to do any such thing. I heard him coming up behind me, but didn’t know what it meant. I didn’t know what to do—what he had in mind. So I ‘took a chance,’ as they say here, and just picked up a vase that was on the table and smashed it on the floor—to show how angry I was. The director shouted: ‘Good girl—hold it—hold it. Get out, Buster, quick—hold it, Margaret, till he’s gone—just that way—there you are—Off.’ ”

Another day, Leahy admitted, she hashed every scene because Keaton changed so much and she wasn’t quick enough to follow. “But he expects this.”

Used to seasoned Sennett veterans like Alice Lake and Sybil Seely, he plainly saw her as a drag on his momentum. “The scenes we threw in the ash can!” he complained. “Easy scenes! We got a good picture; we could have had a fine one. But, my God, we previewed it eight times! Went back and re-shot scenes like mad.”

A structure for the Modern Age emerged: rivalry, jealousy, competition, triumph. “The point of this comedy,” Keaton said, “was that love and the relations of man and woman had not changed since the dawn of time.” The Stone Age scenes were made among the natural formations of Iverson Ranch, where he had shot much of The Paleface. Beery, a club-toting adventurer, makes his entrance on a mastodon; Buster, a “faithful worshipper” at Beauty’s shrine, does the same on an animated brontosaurus. Clad in animal skins, the cast goes through the same cultural rituals as before, with Joe Roberts and Lillian Lawrence playing Margaret’s parents. To gauge his worthiness, Big Joe gives Beery a few hearty blows with his club and reacts approvingly. A similar wallop sends Buster crashing to the ground. Beery challenges him to a sunrise duel with clubs and seconds, and their rivalry escalates into open battle. At one critical point, he lobs a rock at Buster, only to have Buster assume a batter’s stance and whack it back with his club, landing a direct hit.

Keaton shows a double how he wants Margaret Leahy dragged for a traveling shot in Three Ages. This will free him to direct Leahy as she expresses her newfound love for her prehistoric suitor.

“Now, Buster accepted the fact that this rock must be papier-mâché,” said Clyde Bruckman, who was present that day. “But he wouldn’t accept action trickery. It had to be continuous action from the moment the caveman picked it up and heaved it straight through to the moment it homed back and coldcocked him. ‘We get it in one shot,’ he said, ‘or we throw out the gag.’ We set up the cameras for a long profile shot—this rock was going to sail for thirty feet—and we worked for hours. Seventy-six takes, all for one little gag. ‘Okay,’ said Buster, ‘now they’ll know it was for real.’ ”

In February, the Los Angeles Times carried news that huge sets had been erected at United Studios for the scenes in ancient Rome, specifically seventy-five feet of street and a partial reproduction of the Roman Colosseum. The latter was built primarily to serve as the background for a Ben-Hur–style chariot race between Beery and Keaton, the equivalent of the duel of clubs in the Stone Age or a bitterly contested football game in the present. But while Harry Brand’s release boasted of an arena 150 feet high, the actual structure was closer to thirty feet, the illusion completed with a hanging miniature—a scale model suspended in front of the camera. When carefully aligned with the partial set in the distance and populated with tiny dolls (some of which could be moved up and down on sticks), the effect was seamless and gave the impression of great size at a fraction of the cost.

For the scenes in Rome, Keaton indulged in visual puns. When he consults his wristwatch, it is, in keeping with the period, a miniature sundial. His chariot has a license plate, the characters, of course, in Roman numerals, and a spare wheel on the back. When he parks, his helmet functions like a modern anti-theft device. “In that film I did take liberties,” he acknowledged, “because it was more a travesty than a burlesque. That’s why I used a wristwatch that was a sundial, and why I used my helmet the way I did. Fords at that time had a safety device to stop people from stealing the cars, a thing with a big spike which you locked on the back wheel and which looked just like my Roman helmet. So I unlocked my Roman helmet off me and locked it onto the wheel of my chariot. At that time the audience all compared it with the safety gadget for a Ford.”

Dropped into a dungeon with a lion, Buster remembers hearing the story of somebody who made friends with a lion by doing something to one of its paws. Gamely, he examines the lion’s feet and, in a parody of Androcles and the Lion, gives the beast a full-service pedicure. Sprung from the hole, he eludes capture and races to free Margaret, who has been dragged off and imprisoned by Beery. He wrests a long spear from a soldier, commandeers a horse, and vaults to her rescue. “I couldn’t just run over a batch of rocks or something to get to her,” he said. “I had to invent something, find something unexpected, and pole-vaulting with a spear seemed to be it.”

Filming wrapped in March, but the seemingly endless cycle of previews and reshoots continued into May, when Margaret Leahy was finally cleared for travel. In New York, she paused long enough to see George M. Cohan’s So This Is London and sit for interviews with The New York Times and Hearst columnist Louella Parsons. She told the Times that picture players were a hardworking lot and that evenings were often spent watching movies in order to get ideas. “She said that Buster Keaton, with whom she was appearing, often came in at night covered with bruises, with splotches of iodine on cuts received in doing his stunts. The task of producing a picture was a revelation to her, far more involved than she had ever imagined. It was just hard work from beginning to end, and a case of getting up early in the morning and staying on the job until four o’clock in the afternoon. Then in the evening came the orders for the next day’s work.”

Leahy said that she would miss California and showed that she could laugh at the jokes in Cohan’s burlesque of the British, even if she did have to have the occasional line explained to her. When Parsons pointedly asked if she was laughing with the Americans or at them, she replied, “Both.”

While the Keatons were settling into their new home on Ardmore, which came complete with Constance Talmadge, their perennial houseguest, Lou Anger was building a $20,000 place of his own, a nine-room Spanish revival in Hancock Park. Freed from the grind of overseeing six Keaton comedies a year, and ceding responsibility for the Norma and Dutch Talmadge pictures to newly installed associate producer John Considine, Jr., Anger became a man of many enterprises. He owned a petroleum company based on Signal Hill, where “Buster Keaton” was the name of the first producing well, and had his own picture-making entity, Lou Anger Productions.[*2] He was also a partner in Reel Comedies, Inc., which was set up by Joe Schenck to produce two-reelers directed on the q.t. by Roscoe Arbuckle.

At first, Arbuckle attempted to feature himself in a short comedy he wrote with Joe Mitchell called Handy Andy, a sort of return to form after the horrors of the past sixteen months. According to Exhibitors Herald, shooting began at the Keaton studio the week of January 8, 1923, under the direction of Herman C. Raymaker, who had been Fred Fishback’s assistant director back at Keystone. The film was being financed by a group of investors headed by Gavin McNab, and Arbuckle brought Molly Malone, his leading lady from the last five Comique shorts, back as his co-star. Production was expected to take approximately six weeks, but in the face of ongoing protests he called a halt to it all before it was finished.

In May, he was reported as having directed two Al St. John shorts for Fox, and by summer he was back making Handy Andy for Reel Comedies, this time directing the great equestrian clown Edwin “Poodles” Hanneford in the part he had originally conceived for himself, that of a hotel handyman who tries to do everyone else’s job when the help abruptly quits. Under the title Front! the resulting film became the first of five Poodles Hanneford comedies directed by Arbuckle and released through Educational Pictures. Hanneford never caught on with movie audiences, but Lou Anger had somewhat better luck with an Australian-born contortionist and dancer named Clyde Cook, who also appeared in several comedies filmed at the Keaton studio for Educational release.

Costume dramas were all the rage, with Marion Davies topping the popularity polls in the period pictures she made for Hearst, and Joe Schenck encouraging the trend with Smilin’ Through, The Eternal Flame, and Ashes of Vengeance, all hits for Norma Talmadge. On a business trip to New York, he brought back Secrets for Norma; Barbara Winslow, Rebel, a tale of seventeenth-century England, for Constance; and encouraged Buster to make something along the same lines, convinced that interest in such subjects had reached “fever heat.” Indeed, Keaton seemed to acknowledge as much when asked on the set of Three Ages what kind of comedy people wanted. “Refined brutality,” he said. “Put lace on the slapstick. Gild the club. Don’t kill; merely mutilate. That enables the cast to appear in other comedies.”

With Keaton’s second feature in development, some critical staff changes were announced. Eddie Cline stepped away to direct feature dramas under contract to Sol Lesser, and his replacement was John G. “Jack” Blystone. As with Cline, Blystone had written and directed Fox Sunshine comedies, including, coincidentally, all the Clyde Cook shorts, and had just completed his first feature, the Tom Mix western Soft Boiled. Appointed Blystone’s assistant was Arthur Rose, and cameraman Gordon Jennings was engaged to grind European negative[*3] alongside Elgin Lessley. Tommy Gray, meanwhile, had left for Universal, where he remained only a few months before joining Harold Lloyd, who was known to pay as much as $1,000 a week for top talent. “All of us tried to steal each other’s gagmen,” director Leo McCarey said, “but we had no luck with Keaton because he thought up his best gags himself and we couldn’t steal him.”

In their search for a historic germ of an idea, something that would fit on the back of a postcard, someone hit on the notion of dropping Buster into the middle of a feud on the order of the Hatfields and the McCoys. Tentatively titled Headin’ South, the resulting story would first go before the public as Hospitality, then, ultimately, as Our Hospitality. Said Keaton, “On Our Hospitality we had this one idea of an old-fashioned Southern feud. But it looks as though this must have died down in the years it took me to grow up from being a baby, so our best period for that was to go back something like eighty years. ‘All right,’ we say. ‘We go back that far. And now when I go South, am I traveling in a covered wagon, or what? Let’s look up the records and see when the first railroad train was invented.’ Well, we find out: We’ve got the Stephenson Rocket for England and the De Witt Clinton for the United States. And we chose the Rocket engine because it’s funnier looking. The passenger coaches were stagecoaches with flanged wheels put on them. So we built the entire train and that set our period for us: 1825 was the actual year of the invention of the railroad.”

Having settled on an American train with Stephenson’s Rocket as its engine, it fell to Gabe Gabourie to fabricate the thing in his shop on the studio grounds using whatever drawings they could locate.

“We did our own research right up there in the scenario room,” Keaton said. “We were very particular about details, costumes and backgrounds, props and things like that. And never a script. Because when we had what we knew was a story, and had the material and opportunities to get our highspots, we’d bring in our cameraman, our technical man who builds our sets, the head electrician and the prop man—those boys are on weekly salary with us—we didn’t just hire ’em by the picture, they were right there. And we go through what we had in mind on things. They make notes. They know what’s going to be built. The prop man knows the props he’s got to have and the stuff to be built. The electrician knows what he needs in the way of lights and stuff like that. By the time that we’re ready to shoot, there’s no use havin’ it on paper because they all know it anyhow.”

On June 1, while the new picture was taking form, a star-studded fete took place at the Keaton home on Ardmore Avenue. Officially, it was to celebrate Little Buster’s first birthday. It was also to commemorate Buster and Natalie’s second wedding anniversary. Then there was the matter of Constance Talmadge’s divorce from John Pialaglou, the final decree for which had been granted earlier that same day.

“We don’t know which event we are celebrating,” Dutch blithely told a reporter from the Los Angeles Times, “but Baby Buster seems to think it’s his party, so we’ll let him have all the honors.”

And it was around this time that Buster said to Nat, “The kid is a big boy now. Why not come and be my leading lady in my next picture?”

She wasn’t at all sure that she wanted to. “She loved her home,” wrote Eunice Marshall in a profile for Screenland. “She liked to keep house. She liked to take care of the baby herself. A nurse had once let her baby fall ill. Thenceforth she suspected all nurses and took over the entire charge of her son. Screen work would cut in on all this. But Buster insisted. And the thought was not unpleasant.”

An official announcement from Harry Brand’s office appeared in the Times later that month: “MRS. KEATON BACK IN FILMS.” In Brand’s version, it was Natalie who pursued the role, not the other way around. “She went to Lou Anger, executive manager of Buster’s studio,” the unlikely story went, “and prevailed upon Anger to intercede for her. Between the two of them Buster was won over.” The release added that Baby Joe, known within the family as “Winks,” was to have a part in the picture too, but in the Keaton tradition he was a seasoned pro at the age of twelve months—he had already appeared with his Aunt Dutch in her upcoming picture Dulcy.

Three Ages had its world premiere in London on June 25, 1923, and befitting the enormity of the contest that resulted in the casting of Margaret Leahy, it happened before a capacity audience at Marble Arch Pavilion that included Princess Alice and the Duke of Athlone. Leahy made an introductory appearance, humbly promising to “work very hard to be better and better as my career goes on,” and the audience cheered her first appearance on-screen. A private showing hosted by David Lloyd George, the former prime minister, followed for the Duke and Duchess of York, the royal newlyweds of the day and the future parents of Queen Elizabeth II. The British release of Three Ages took place on July 2, when it simultaneously opened in twenty-four theaters. Keaton, immersed in preparations for the filming of Headin’ South, couldn’t make the London premiere and was happy to leave the attention to Leahy, who toured the country doing appearances and was perhaps a bigger draw with the British public than Buster himself.

Casting the new movie became a family affair. A year after separating from his wife over his drinking, Joe Keaton had taken the pledge, and with Nat and Little Buster already on board, it was a natural fit to give him the role of the Rocket’s high-kicking engineer. Joe Roberts was the obvious choice for the paternal head of the Canfield clan, with New York stage personality Craig Ward and Ralph Bushman (son of matinee idol Francis X. Bushman) as his two trigger-happy sons. Filling out the principal cast were character actress Kitty Bradbury, known for her work with Griffith and Chaplin, and stage veteran Monte Collins, both of whom had appeared with Keaton in the past. Filming began on June 30, initially in Grass Valley, then moved fifty miles east to Truckee, which in the wintertime had served as the setting for The Frozen North and would now, in the summer, represent the countryside to which Willie McKay must return to claim his inheritance.

Anticipating a three-week stay, the Keaton company brought two railcars stuffed with costumes, properties, and what appeared to be a miniature railway and track. Having settled on the design of the hybrid train, Keaton effectively made the Rocket a fully developed character in the story, lovingly depicting its many eccentricities in an extended sequence that could serve as a primer on early rail travel.

“They’re naturally narrow-gauge,” he said, “and they weren’t so fussy about layin’ railroad track [back then]—if it was a little unlevel, they just ignored it. They laid it over fallen trees, over rocks. So I got quite a few laughs ridin’ that railroad. But when [in the picture] I got down South to claim my father’s estate, I ran into the family who had run us out of the state in the first place. And the old man of the outfit wouldn’t let his sons or anybody shoot me while I was a guest in the house ’cause the girl had invited me for dinner. Well, I’d overheard it and found out. As long as I stayed in the house I was safe.”

The rickety train, composed of five cars including a flat, open-air baggage tender and two six-passenger compartments, moves at a deliberate pace, so much so that Willie’s loyal dog can easily keep up. The title, which suggests Clyde Bruckman’s hand:

Onward sped the iron

monster toward the

Blue Ridge Mountains.

A tramp, caught stowing away, can slow the entire train by merely grabbing hold of it. The track sags and roils as it moves along, and the cars buck roughly as they pass over a fallen tree. A jackass at the side of the track refuses to budge, and it proves easier to nudge the track away from him than to reason with the animal. A field of rocks creates the effect of a prehistoric roller coaster, the passengers’ heads banging against the tops of the cars. When the train leaves the track entirely, the only way they can tell is that the ride is suddenly smoother. Up front, the engineer fails to notice because he is busy cooking his lunch in the firebox. Willie, it turns out, has been seated next to the Canfield girl the entire time. She steps off the train and runs into the arms of her father and elder brothers. Willie collects his things and goes off in search of the McKay estate. His dog, hardly winded, has made the entire trip on foot.

If Three Ages represented a transitional and somewhat uncertain bridge between shorts and features, Our Hospitality was a mature work of visual storytelling, richly textured and combining the comic and the tragic so deftly it marked an astonishing advancement for a man who had been directing his own films for just three years. “Once we started into features,” said Keaton, differentiating between shorts and what he termed “legitimate” stories, “we had to stop doing impossible gags and ridiculous situations. We had to make an audience believe our story.” Gone were the anachronistic absurdities of Three Ages, replaced by the quaint and charming authenticities of the early nineteenth century. “I don’t know why it is, but I know it’s a fact, that every gag used in a straight comedy has to be logical at bottom. There must be an element of possibility in everything that happens to me or the audience is immediately resentful.”

Three generations of Keatons on the set of Our Hospitality (1923).

Keaton also returned to a structural convention he first hit upon with The Paleface, opening his second feature comedy with a starkly melodramatic prologue in which Buster Jr. played his own father at the age of one.

“I use the simplest little things in the world,” Keaton said in a 1965 interview, “and I never look for big gags to start a picture. I don’t want them in the first reel, because if I ever get a big laugh sequence in the first reel, then I’m going to have trouble following it later. The idea that I had to have a gag or get a laugh in every scene…I lost that a long time ago. It makes you strive to be funny and you go out of your way trying. It’s not a natural thing.”

It is indicative of the control that Keaton exerted over every aspect of the production that Jack Blystone became disillusioned and asked for his release after just a week on the job. Lou Anger acceded to the request so that Blystone could return to Fox under a new three-year contract, even as Keaton pronounced himself quite pleased with his work. “He was a good man, excellent,” he said. Blystone remained with the company through the remainder of the shoot, and would go on to make sure-handed dramas along with comedies, eventually directing Will Rogers, Spencer Tracy, James Cagney, and Laurel and Hardy.

The American premiere of Three Ages took place in San Francisco on July 14, and Buster and Natalie trained in from Truckee to witness a Sunday performance. Display ads for Loew’s Warfield heralded the “First World Showing of the World’s Funniest Comedy” combined with a live prologue titled “Dances of Three Ages.” The Chronicle reported large audiences on Saturday and Sunday “for Buster is a ‘wham’ with the public.” The paper’s reviewer praised “long stretches of splendid fun” and was certain the picture had cost a lot of money. The only sour note was Margaret Leahy’s presence in the cast. “She is nice looking, big and healthy, and perhaps could do a good day’s washing, but as a beauty! If that’s the best England can do, the country had better give up all pretensions to feminine pulchritude.”[*4] Variety reported a record gross of $17,500 for the week, easily besting Universal’s heavily promoted Merry Go Round, even with the added advantage of having co-director Erich von Stroheim in town filming his first Goldwyn production, Greed.

Location work stretched over much of July, time enough to capture the Rocket’s uncertain journey as well as harrowing scenes made on the rapids of the Truckee River. After escaping one of the murderous Canfield boys, Willie is caught in the current rushing toward a deadly waterfall, Virginia Canfield in a small boat paddling desperately to his rescue. But then she is bucked clear of the boat, and in a sequence remindful of the ice floe rescue in Griffith’s Way Down East, it falls to Willie to try to save her. “For that scene in the rapids, the one where I’m trying to catch Natalie—someone doubled for her in those shots, of course—we picked the best rapids from a pictorial point of view, a two-hundred-yard stretch where the water moves fast and white. I’m supposed to grab onto a sixteen-foot log and float out into the bad water.”

Gabe Gabourie rigged a holdback wire around the log and ran it back about sixty feet, where, securely wrapped around a baseball bat, it was held fast by three men. The plan was to get close-ups of Willie in the furiously churning water before adjourning to a calmer part of the river for long shots. With the cameras turning, Keaton could feel the wire give, a break so soft it was barely audible. In moments, he and the log were being swept away, the men hollering and racing through the rocks and the underbrush along the shoreline. “I sure as shooting have to shed that log or it will beat me to death against the boulders. So I kick loose and sprint ahead. Can’t look around, but I know that log is right on my tail. I’m hitting boulders now with my hipbones and knees, and a couple I hit so hard on my chest that I go clear up out of the water and over. The main thing is to keep from whirling.”

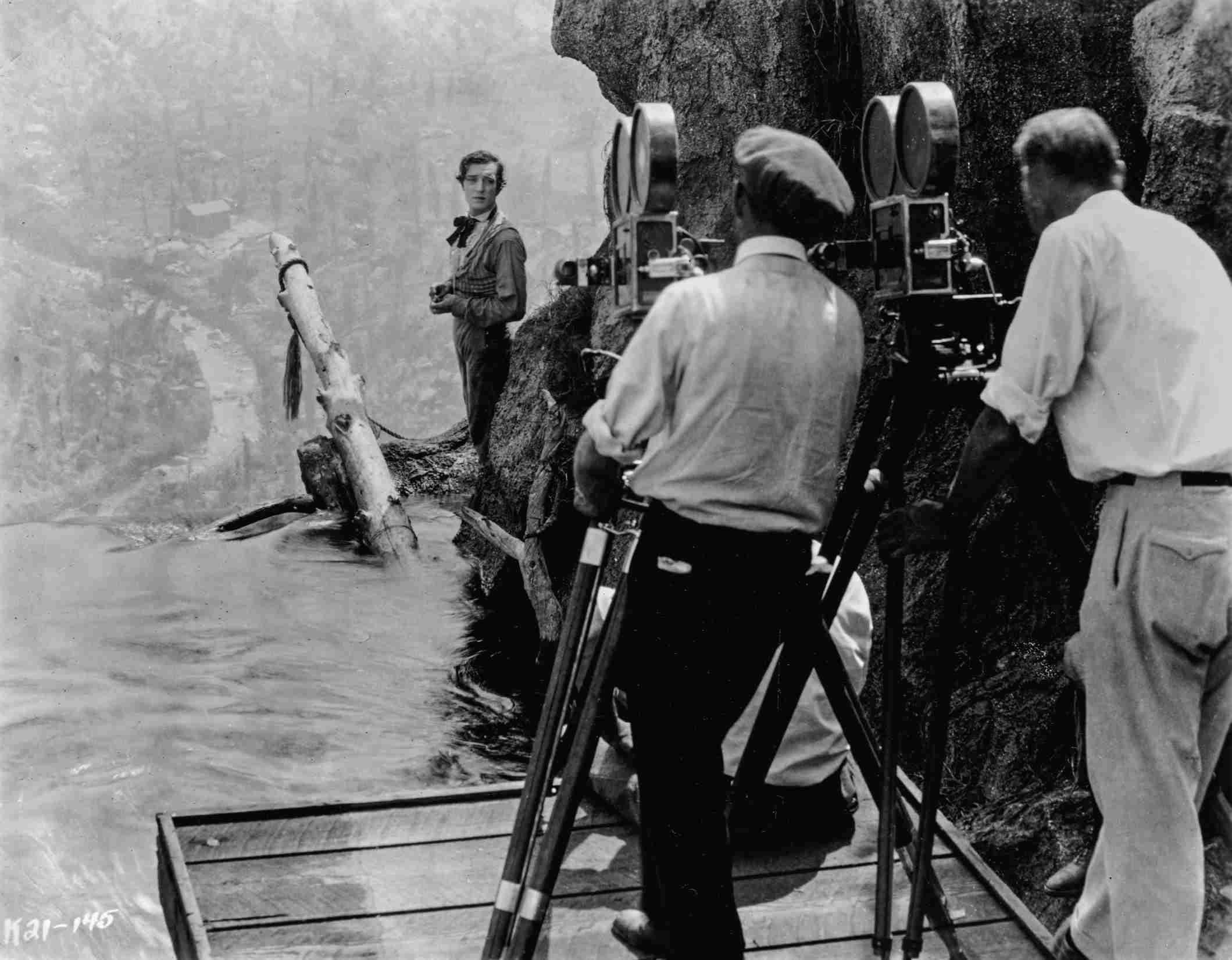

The waterfall for Our Hospitality was constructed over a T-shaped pool on the United Studios lot.

Fighting for breath, he felt the water starting to calm and then found himself submerged in a foot or more of foam. “You don’t breathe very well in foam, and you sure as hell can’t swim on top of it. I later found that there was three-hundred yards of that foam ganged up at the end of the rapids. It was a bend in the river that saved me.” He caught some overhanging branches and pulled himself ashore, lying facedown and gasping for breath. He couldn’t tell how long it took the men to reach him through the underbrush, but it seemed like ten minutes.

“Did Nat see it?” he asked.

Yes, he was told, she had.

“Did you get it?” he wanted to know.

Yes, Lessley responded. Both cameras.

They broke camp at Truckee, returning to Lillian Way to shoot interiors and film Virginia’s rescue from the safety of a specially constructed waterfall on the United Studios lot, built over the same T-shaped pool where Buster made his famous dive all the way to China in Hard Luck. With Virginia rapidly approaching in the water, Willie anchors himself to the log now wedged in the rocks with a rope around his waist. Perched on a treacherous ledge, he awaits his chance, and as the water carries her to the precipice and begins to pull her over, he swings out and grabs her at the last possible moment. Swinging wildly, he manages to drop her to the ledge below and then struggles mightily to pull himself clear.

Keaton prepares to shoot the waterfall rescue of Virginia Canfield. Elgin Lessley (in cap) shoots the domestic negative while Gordon Jennings exposes a duplicate to be used for European prints. A miniature background lends a striking realism to the effect.

Joe Roberts poses for a still depicting the climactic scene of Our Hospitality. Flanking him are Ralph Bushman, Monte Collins, Keaton, Craig Ward, and Natalie Talmadge.

“We had to build that dam,” said Keaton. “We built it in order to fit that trick. The set was built over a swimming pool, and we actually put up four eight-inch water pipes with big pumps and motors to run them, to carry water up from the pool to create our waterfall. That fall was about six inches deep. A couple of times I swung out underneath there and dropped upside down when I caught her. I had to go down to the doctor right there and then. They pumped out my ears and nostrils and drained me, because when a full volume of water like that comes down and hits you and you’re upside down—then you really get it.” The figure he caught was a cleverly weighted dummy dressed in the character’s water-saturated clothing. “I think I got it on the third take. I missed the first two, but the third one I got it.”

Natalie gave an excellent account of herself in the film, game for a lot of the physical stuff, even though she was aware that she was once again pregnant. Eunice Marshall watched her go through a scene with Ralph Bushman at the studio, costumed in a frock of rose taffeta and a full crinolined skirt: “She was playing a daughter of the Old South and seemed to have gained poise, having learned a thing or two about makeup.”

But Natalie, she discovered, was dubious about continuing as Buster’s leading lady. “I’m not sure whether I shall do another picture after this one or not. I hate to be away from the baby so much. Of course, he is with Mother and in good hands. But I don’t want him to know anybody else better than me. Every morning I bathe him and dress him before coming to the studio. I miss being with him during the day. But it is pleasant here, too. They are very patient with me. It is four years since I have done anything in pictures, you know.”

When the baby was photographed for his brief cameo in the prologue of the movie, he developed a case of “Klieg eyes” from exposure to the carbon arcs used in filming. Marked by conjunctivitis and watering, the temporary condition, which afflicted many screen personalities, resulted in his immediate retirement from pictures. Much more serious was a stroke suffered by Joe Roberts on August 17 that brought production to a halt. Roberts had not been well, and it was necessary to double him on multiple occasions while on location in Truckee. He was referred to Dr. Louis J. Regan, who had offices in the Security Bank building on Hollywood Boulevard and saw a number of industry patients. As part of a thorough examination, the doctor drew blood and ordered a Wassermann test, which confirmed a preliminary diagnosis of late-onset neurosyphilis, the infection tracing back some thirty years. There was nothing to be done; Big Joe was dying.

Facing seizures, dementia, and eventual paralysis, Roberts was ordered to bed. Keaton shot around him, but Joe knew the picture couldn’t be properly completed without him, and after a brief convalescence he returned to Lillian Way to finish his part. In a severely weakened state, he rested on a couch between shots while others attended to his makeup and wardrobe. Then, mustering his strength and favoring his right side, he managed to hide his infirmities and deliver a strikingly shaded comedic performance in what he now knew would be his final picture. Particularly affecting is his climactic scene in which he comes to the realization that after generations of warfare he must now accept a McKay into the family. Pistol in hand, he registers shock, anger, bewilderment, resignation, and, finally, fatherly love as he kisses his newly married daughter on the forehead and gathers her into his arms, slowly extending a hand of genuine friendship and welcome to his new son. It is a scene that would challenge the most experienced of actors, yet Roberts gives each successive beat a thoroughly natural reading. After years of playing the narrow parameters of low comedy, here he showed in his final moments on-screen what a fine dramatic actor he could be, and the heights he might have scaled had he been permitted a longer life.

With his scenes in the can, Joe retired to the new eight-room house he had built for his wife and family to await the inevitable. When the picture was cut together under the title Hospitality, he was too weak to attend a Glendale preview under his own power and had to be carried into the theater. According to Harry Brand, the showing took place on the night of October 27, 1923, and Roberts returned home that evening with the knowledge that he had delivered the finest performance of his career. A few hours later, at just minutes past midnight, a second stroke claimed him at the age of fifty-two.