14

Steamboat Bill, Jr.

IN MANY WAYS, 1926 was the year of Joseph M. Schenck. His makeover of United Artists was the talk of the industry, with his own productions, up to six a year, helping fill the pipeline for the 1926–27 season. To gear up for such a schedule, he formed Art Finance Corporation to act as the nominal producer of Rudolph Valentino’s The Eagle. Then Art Finance created Feature Productions, Inc., to function as a production entity, commencing with The Bat, a hugely popular melodrama, and Valentino’s Son of the Sheik. Schenck was president of the Federal Trust and Savings Bank of Hollywood, and a director of A. P. Giannini’s Bank of Italy, where he was in charge of all motion picture and theatrical loans. He was also heavily invested in real estate, including an entire neighborhood in San Diego he called Talmadge after his wife, Norma, and her sisters.

In February, Schenck arranged the sale of United Studios to Famous Players-Lasky for $1,250,000 with the intent of moving most UA production activity to the nearby Pickford-Fairbanks lot, which would be expanded accordingly. In July, a profile in the Los Angeles Times estimated his personal wealth at somewhere between $40 million and $50 million. In October, Variety issued a special “Joseph M. Schenck Number” comprised, in part, of ads and testimonials from friends and associates. “The thing that has impressed me most after over ten years’ business, family, and social contact with Joe is his fairness,” Buster Keaton wrote. “There is no fairer man than he in the world—and I’m sure the world, assuredly the amusement world, knows that. I have never heard him speak ill of anyone. He prefers to leave many things unsaid. I never really realized the meaning of tolerance until I became intimately acquainted with the man whom the public knows as a twentieth century business and amusement king, but whom I know as a prince among men….From the day I went into pictures, Joe Schenck has been like a father, brother, pal, and employer, all in one. He advanced me as fast as I deserved. If I ever became discouraged, he snapped me out of it.”

Ironically, Keaton wrote these words at just about the time his relationship with Schenck began to unravel. A key element of the strategy to revitalize United Artists was to establish a string of branded theaters in major cities to showcase product on a pre-release basis. Douglas Fairbanks had pioneered the approach with The Thief of Bagdad, leasing legitimate theaters where no suitable film theaters could be found and settling in for extended runs before putting the picture into general release. Schenck envisioned twenty such theaters, and in May 1926 formed United Artists Theatre Circuit, Inc., with Sid Grauman and Lee Shubert to build six within the first twelve months. “The problem of sites is the main one that confronts us at the present moment,” he told Edwin Schallert of the Los Angeles Times, “and I wish that it might be solved as easily everywhere as in Los Angeles.”

L.A. was sprawling and not as concentrated or overbuilt as Chicago or New York, where situating a new theater, even an intimate one along the lines of Shubert’s 1,600-seat Astor, would require displacing an existing structure. Wary of building new houses outside of established bright-light districts, Schenck felt he needed someone deeply experienced in both real estate and show business for the critical task of scouting sites in such diverse places as Denver and Philadelphia, and in August, while Keaton was working in Oregon, he settled on Lou Anger for the job. Apart from budgeting, Anger’s involvement with The General had been limited, and he had delegated much of his on-site authority to Gabe Gabourie, who as production manager took on logistical responsibilities while business manager Al Gilmore attended to financial oversight and purchasing. By the time Keaton returned to Hollywood, Anger was in New York and nobody was in charge of the studio other than Keaton himself. Gabourie and Gilmore continued in their roles until October, when Schenck appointed publicist Harry Brand as Anger’s replacement.

Keaton had a curious relationship with Brand, who had been with Schenck off and on since the Arbuckle days and was generally well liked. In 1925, Buster compiled an irreverent dictionary of studio personnel for private consumption, and included a wicked dig at Brand, who had worked a stretch for Los Angeles mayor Meredith Pinxton “Pinkie” Snyder and founded the Western Associated Motion Picture Advertisers Society (WAMPAS) in 1922:

Publicity man—Impossible person who writes reams of copy for newspapers, most of which is not printed. Member of WAMPAS with no other bad habits, is addicted to showing boss clipping that appeared in metropolitan newspapers with circulation of 150. Admits he’s good, but can’t prove it. Failure as newspaper man.

Several months later, while Keaton was away shooting Go West in Arizona, Brand transferred to New York to organize an exploitation department for United Artists, and was replaced at the Keaton studio by a man named Don Eddy, who had been Valentino’s press agent. Keaton later told Rudi Blesh it was his own suggestion that Schenck make Brand his new studio manager, but why he would do such a thing is unclear. He evidently considered Brand a lightweight, but Brand may simply have been the devil he knew, preferable to some unknown entity Schenck might bring in from the outside. Whatever the reason, Brand arrived back in Hollywood just as Battling Butler was looking to be the biggest hit of Keaton’s career.

Of all of Buster Keaton’s feature comedies, Battling Butler was the most conventional, a story any of a dozen leading men[*1] could have managed, if not necessarily with the distinction and acrobatic dexterity Keaton brought to the role. Unlike his other pictures, there were no big ideas, no astonishing chases, no camera tricks to speak of. The comedy was purely situational, the plot accessible to viewers who found Sherlock Jr. or Go West more challenging than funny. And when it was let out, pre-release, to markets such as Philadelphia and San Francisco, it led all competitors. In New York, where it opened at the Capitol Theatre on August 22, it went head-to-head with The Black Pirate and shattered the house record for a Sunday. All the Manhattan dailies gave it a warm welcome, some offering unabashed raves.

“Not since the halcyon days of The Navigator has the adamant Buster Keaton appeared in as clever a slapstick comedy as Battling Butler,” wrote Eileen Creelman in the Sun, echoing popular sentiment across the board. “Go West and Seven Chances, the non-smiling comedian’s previous films, cannot be compared with it, and, indeed, there is no reason why they should be, for Battling Butler is far beyond them in cleverness, wit, and good robust fun.”

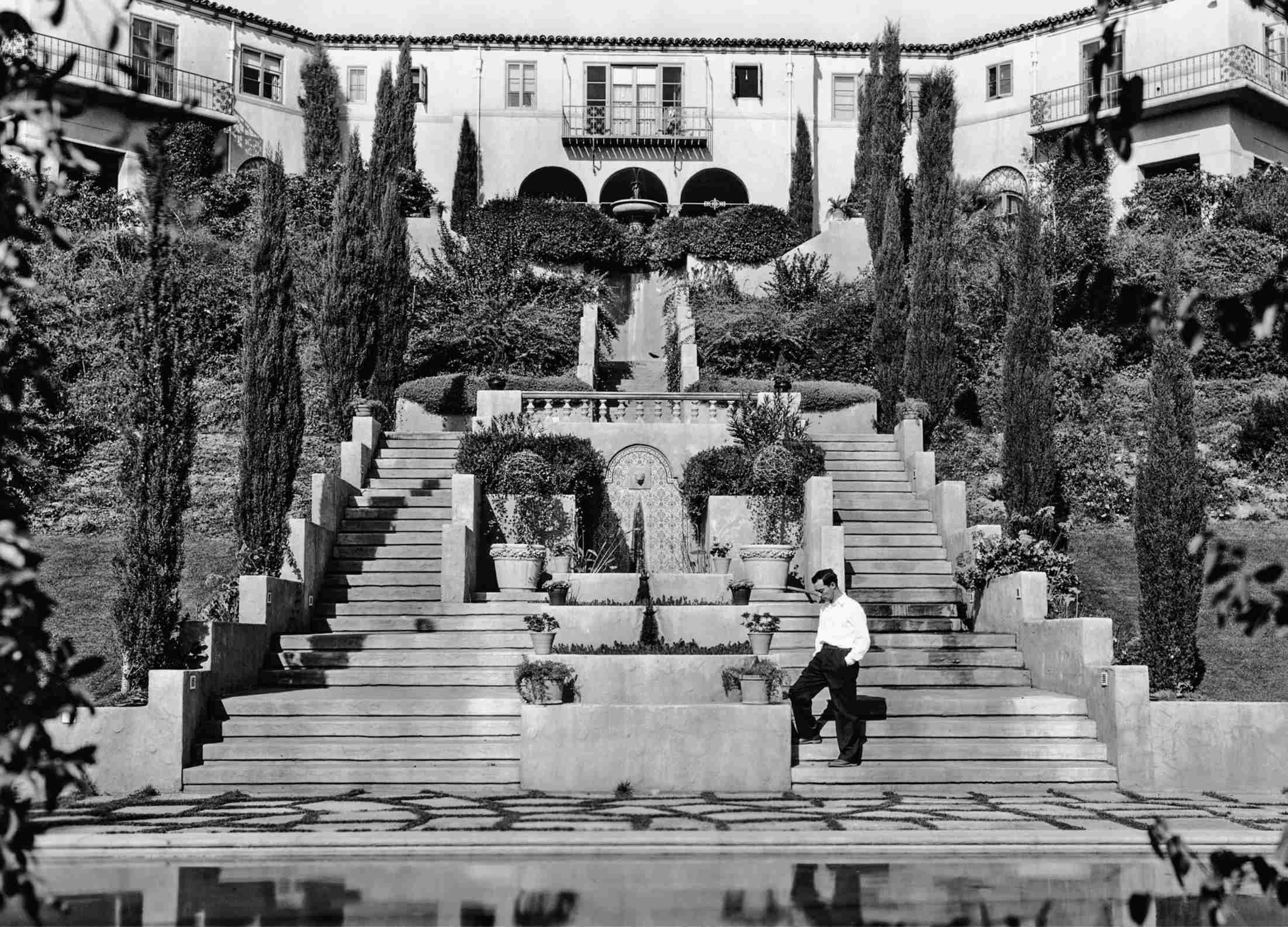

Keaton on the grounds of his Italian Villa in Beverly Hills. The mansion and its pool area would later serve as a setting for Parlor, Bedroom and Bath (1931).

By the time of its official release on September 19, Battling Butler had already played a number of major cities, where it invariably opened strong, reflecting a devoted following for Keaton’s work, but sustained itself in no way as dependably as comparable releases from Chaplin and Harold Lloyd, the latter typically enjoying eight- or ten-week runs to Keaton’s one or two. In March 1926, Lloyd’s The Freshman passed $2 million in rentals, an unprecedented figure for a feature comedy. Battling Butler, by comparison, would eventually see worldwide rentals of $749,000—a personal best for Keaton but nowhere near Lloyd’s career average. Lloyd’s greater popularity was also reflected in his annual income, which was estimated in a study for Motion Picture Classic to be $2 million, or around $40,000 a week. In the same article, Keaton’s annual income was pegged at $200,000 or roughly $4,000 a week.

In August 1926, while he was shooting interiors for The General, Keaton’s new house in Beverly Hills was being landscaped. Dozens of palm trees, rendered homeless by the widening of Wilshire Boulevard, were moved to the property. “It was a two-story mansion with five bedrooms, two additional bedrooms for the servants and a three-room apartment over the garage for the gardener and his wife, who worked as our upstairs maid,” he enumerated. “This made six servants with a cook, butler, chauffeur, and governess.”

He had poured $200,000 into the design and construction of the place, and was poised to spend another $100,000 furnishing it to Nat’s liking. In size and formality, he indulged a passion for Italian architecture his wife had nurtured since a tour of Europe in 1920, when she and her family visited Rome, Florence, Milan, Venice, and the Lido. (“These old-world storied cities held a particularly potent charm for Natalie,” her mother wrote.) And while there can be no doubt that Keaton’s home of preference would have been the relatively modest one he designed and built for himself and his family on Linden Drive, he came to enjoy tricking out the Italian Villa at 1004 Hartford Way almost as much as did his wife.

“I designed some of the furniture myself—the king-sized bed that my wife wanted for her room, the fancy bed I put in mine, and a wonderful pair of high bedroom bureaus of dark oak, with a full-length mirror set between them. I had these pieces built by the carpenters at the studio.”

One day, Keaton proudly walked Nicholas Schenck through the house, Schenck, of course, being Joe’s younger brother, vice president and general manager of Loew’s Incorporated, and a major stockholder in Buster Keaton Productions. Nick whistled admiringly as Keaton pointed out such details as the trickling water fountain in the conservatory off the main entrance, the intricate carvings fronting the stone fireplace that dominated the living room, and the imported tiles that made up the checkerboard pattern on the floor of the solarium. In the playroom, with its exposed beams, its projection booth, and its thirty-foot throw to a sliding screen that, when extended, perfectly covered the windows, he had a pool table, gaming supplies, and a hidden room that served as a Prohibition-era bar with access via the booth to a well-stocked cellar. Outdoors, four tiers of lawns, gardens, and white limestone steps formalized by Italian cypress trees descended to a Venetian-tiled swimming pool and a vast expanse of trees and wildlife beyond.

“I hope, Buster, you aren’t going over your head on this place,” Nick, who knew down to the penny what Keaton was clearing on an annual basis, confided in a whisper.

In December 1926, Arthur McLennan, the new publicity and advertising chief for United Artists, put out word that The General would have its world premiere in New York on January 1, 1927. The Capitol had been Keaton’s Broadway home since The Navigator, and in the wake of Battling Butler’s sizzling two-week stay, the house and its managing director, Major Edward Bowes, were happy to have it, even though Keaton was no longer releasing through Metro. The plan, however, hit a snag when three M-G-M pictures took precedence in Loew’s flagship house—Valencia, Mae Murray’s final film for the studio, which was slipped in to take advantage of an extraordinarily busy holiday season; A Little Journey, an unfortunately titled romance with Claire Windsor and the up-and-coming William Haines; and Clarence Brown’s Flesh and the Devil with John Gilbert and Greta Garbo, which pulled sensationally and was promptly extended for two additional weeks, giving it the first three-week engagement in the theater’s history.[*2]

Effectively shut out of the New York market for the entire month of January, The General was left to languish in a no-man’s-land of regional bookings. It had its world premiere—such as it was—in Tokyo on December 31, 1926, Japan having emerged from a virtual shutdown of all theaters and nonessential businesses during the illness and eventual death of Emperor Taishō. Stateside, one of the first venues to get it was the Liberty Theater in Carnegie, Oklahoma, and word came back that it landed with a thud. “Amusing,” sniffed the house manager, “but not funny. Not one good laugh in the two days’ showing.”

Portland got the picture next, with a four-week run anticipated, followed by its London opening on January 17. Flesh and the Devil was extended a fourth record-breaking week at the Capitol, causing UA’s McLennan to creatively point out that The General had already achieved a record of its own—for the longest “lobby run” at the theater. Meanwhile, the picture went up against Harold Lloyd’s The Kid Brother in Kansas City, where the Star lent strong editorial support as well as two favorable reviews, and Chicago, where bad weather caused it to slip after a strong opening.

The General finally found its way into New York on February 5, 1927, after Flesh and the Devil was essentially forced out of the Capitol. With the mixed evidence already at hand, Schenck and the high command at UA feared it wasn’t another Battling Butler, although at a negative cost of $415,232 it represented a greater investment. Among the first to register a public opinion was Martin Dickstein, the insightful young critic for The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, who reported an enthusiastic opening-day crowd. “Hardly a foot of celluloid is ground out of the camera but the stoical comedian hasn’t some amazing new trick to draw out of his sleeve to the renewed pleasure of the audience. Keaton’s gags appear to be spontaneous and perfectly timed, while as much cannot be said for Harold Lloyd in The Kid Brother at the Rialto. There is rhyme and reason to Buster’s nonsense, as no one would deny if, indeed, time could be found for denial between the hysterical outbursts at the Capitol.”

Dickstein’s notice was knowing and generous, but it didn’t take long for less satisfied voices to drown him out. “The General is no triumph as a comedy,” judged the same Eileen Creelman who lavished such praise on Battling Butler, “but it does not fail as entertainment. Mr. Keaton’s special admirers will probably find him funny anyway. Others may receive enough melodramatic thrills to comfort them.” Significantly, Creelman classified the film a “historical drama—with comic moments” and lamented what she saw as a trend of feature comedians longing to play heroes, calling out The Kid Brother and Raymond Griffith’s Hands Up, another Civil War story, as examples. “This epidemic of drama among the comedies rouses wonder as to The Circus. Will Charlie Chaplin attempt a serio-comic version of [the vivid German drama] Variety or, worse yet, Pagliacci?”

More withering was Variety’s Fred Schader, who branded The General an outright flop. “The story is a burlesque of a Civil War meller. It opens with what looks like a real idea, but never gets away from it for a minute. Consequently, it is overdone….There are some corking gags in the picture, but as they are all a part of the chase they are overshadowed. There isn’t a single bit in the picture that brings a real howl. There is a succession of mild titters….The General is a weak entry for the deluxe houses. It is better geared for the daily change theaters, as that is about its speed.”

Within the trade press, Film Daily was dubious while Billboard cheered: “Keaton’s previous picture in no way begins to compare with this one. Book it in spite of cost.”[*3]

In The New York Times, Mordaunt Hall dismissed it as a “somewhat mirthless piece of work,” and of the twelve other major papers, nine clearly agreed while another two straddled the fence. (“The camera work is good, the settings excellent, the gags among the funniest we have seen,” hedged the Telegraph, “and yet the piece lacks life.”) The Evening Post stood alone among New York dailies in suggesting it had “a quaint air of quiet thoughtfulness about it which seems to reflect very accurately the attitude and personality of the comedian himself…the humor is seldom obvious and never boisterous—an undercurrent rather than a wave of laughter…probably lots of people, used to the something-funny-every-second school of comedy, will not think it funny at all.”

From his perch across the East River, Martin Dickstein, who endorsed the Post’s summary, reacted with astonishment:

Such uncommon comedians as Chaplin and Keaton do not fashion their humor for the delectation of the zanies who must have that humor plastered in custard patties across the screen or driven home with the aid of a pile driver. Buster has made a financial faux pas, perhaps, by preferring to aim The General at the lofty-browed minority rather than at the more numerous minds which, for want of a better simile, may be compared to those of taxi drivers. He has, however, demonstrated that he is a facile comedian who prefers to gambol above the heads of sheep rather than to squat upon his haunches and sheer them of their fleece. The idea of The General was, in itself, a brilliant one. Few among our more important screen comedians could have visualized the possibilities for humor which lay in that Civil War episode where ten Union soldiers made their way into Confederate territory and kidnapped a locomotive from the soldiers of General Lee….It required no little ingenuity to infuse humor and suspense into a narrative which was necessarily limited in scope to the single-track system of the old Western and Atlantic road through Georgia….These territorial limitations, of course, did not permit Buster to hang hazardously from lofty window ledges, nor did it afford him opportunity to be dragged in the dust while he clung desperately to a horse’s tail. I have seen these things done on other screens and invariably they have elicited long and noisy laughter. But Keaton very snootily has proved himself to be above such low business, for which, apparently, he has failed to win the approval of the critical ladies and gentlemen who write about the cinema for the newspapers. However, if you like comedy that is not too painfully obvious, and if you can ascertain a subtle bit of humor without sitting down to mull over it for an hour or two, I give you The General—a comedy for the exclusive enjoyment of the matured senses.

Keaton rarely spoke of the critical drubbing he took for The General, in part, he said, because he never paid much attention to reviews. “I hadn’t because I’d been reading house notices since I was born, and was used to that. This critic likes you and this one don’t, so that’s that.” Typically, he threw himself into his work, having started a new picture, and was deeply immersed in shooting it when the worst of the notices were published. Still, Bob Sherwood’s scolding in Life must have been particularly wounding, given that Keaton considered him a friend and faithful advocate.

“It is difficult,” Sherwood wrote, “to derive laughter from the sight of men being killed in battle. Many of [Keaton’s] gags at the end of the picture are in such gruesomely bad taste that the sympathetic spectator is inclined to look the other way.”

There had, of course, been other war comedies, most notably Chaplin’s Shoulder Arms and, more recently, Paramount’s Behind the Front, but none that had so frankly exploited the horrors of war in the service of comedy.

“Well, he was a little sensitive about that,” Keaton allowed. “Because you’ve had to kill people in comedies. You’ve done that for years. But as a rule, if we could help it, we didn’t.” For Keaton, the timing was problematic in that The General appeared when the biggest hit of the era was M-G-M’s grueling wartime tragedy The Big Parade, a near-flawless rendering of the American experience in France that Sherwood immediately felt could be “ranked among the few genuinely great achievements of the screen.” The picture was in its sixty-fifth week at the Astor Theatre on Times Square when The General was grudgingly afforded its solitary week at the Capitol, and undoubtedly its impact rewired the brains of reviewers and moviegoers alike in terms of what they would tolerate in future depictions of war on the screen. One of The Big Parade’s signature sequences portrayed an American advance on enemy positions in a forest, a tense rhythmic march in which soldiers seeing their first action are methodically picked off by German sniper fire. While hardly flippant, Keaton’s movie nonetheless caught audiences at a time when they were in no mood to laugh at a scene of a Union sniper targeting rebel soldiers as Johnnie Gray attempts to direct their cannon fire.

The returns at the Capitol weren’t dismal, but neither did they soar to the level of The Navigator or Battling Butler. The General finished the week respectably enough with a gross of $51,000 and wasn’t held over, while Butler, which finished its comparable week at $57,600, was. All the bad luck coming Keaton’s way may have persuaded Joe Schenck that a gala premiere was in order when The General reached Los Angeles. The venue was Sid Grauman’s 3,600-seat Metropolitan, the largest movie palace in the city, and the opening was set for Friday, March 11, with more than fifty picture personalities in attendance, headed by a contingent of United Artists stars that included Keaton and Marion Mack, Norma and Constance Talmadge, Estelle Taylor, and John Barrymore. Heralded by sun arcs and banks of Klieg lights illuminating the theater’s Sixth Street entrance, as well as a performance by the 160th Infantry Band of the California National Guard, the film packed the theater “to within an inch from the roof.” According to the Los Angeles Evening Herald, “uproarious applause” greeted every appearance Keaton made on-screen, and “torrents of laughter” flowed without interruption. “Buster was in the audience last night along with a number of other film celebrities and he received an ovation that must certainly have inspired one of those rare smiles that optimistic fans have as yet failed to see.”

Katherine Lipke’s lukewarm notice in the Saturday Times, headlined “COMEDY IS LOST IN WAR INCIDENTS,” was countered by young Louise Leung’s perceptive review in the Los Angeles Record: “The General, especially recommended to theatergoers by Frank Newman, manager of the Metropolitan, indeed is the quintessence of modern movie comedy, renovated and enhanced at every possible turn until virtually the entire slapstick order had been eliminated in favor of a coherent, fast-moving series of mishaps that keep the audience in a state of suspense and laughter until the end….The picture must take its place as one of the best examples of modern comedy construction.”

Slipped to Grauman on a flat $5,000 rental, The General endured a disappointing week at the Metropolitan, where it grossed about $25,000 and was outperformed by Slide, Kelly, Slide, a routine baseball picture, at the much smaller Loew’s State. Actress Louise Brooks thought something more basic than the film’s quality was at fault, and remembered hearing nothing about the picture prior to its opening. “It was the title The General,” she wrote in a 1968 letter to Kevin Brownlow. “We thought Buster was playing a general, a Southern general. Not funny. As an Englishman, you cannot understand that the Civil War killed thousands of Americans fighting against their own families, almost wrecking our country. Nobody connected The General with the name of an engine. Many people stayed away. Those who saw The General were puzzled.”

Once word got around as to what to expect, audiences became more accepting of the picture. Bookings increased in small markets, which had been unusually resistant to it compared to other United Artists releases, such as The Winning of Barbara Worth and Mary Pickford’s Sparrows. A manager in Gunnison, Colorado, actually reported good business and positive comments. “Think it the best Keaton since Go West,” he wrote. “Sorry we played it during our dull season.” Up in Toronto, The General was a surprise hit, drawing better than The Kid Brother, which was pulled after three lackluster weeks.

There is evidence The General had staying power beyond Keaton’s other UA features, with more prints in circulation and domestic bookings extending well into 1929. Ultimately, it would log rentals in the United States and Canada of $486,465. Adding in likely foreign rentals in markets such as England, Germany, Italy, and the Far East, worldwide projections easily surpass $800,000, making The General, contrary to popular belief, Keaton’s highest-grossing feature yet. In 1962, it was a runner-up in Sight & Sound’s decennial critics’ poll of the greatest films of all time, and in 1972, fifty-five years after its release, it entered the top ten, placing it in the company of Citizen Kane, Battleship Potemkin, and Wild Strawberries. And in 1989, when the National Film Registry of “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant” motion pictures was established, the Librarian of Congress selected The General as one of the first twenty-five titles to be enrolled, along with such other American treasures as Casablanca, Gone With the Wind, The Maltese Falcon, and The Wizard of Oz.

The General closed at the Capitol on February 11, 1927, and the picture that followed it into the massive theater was M-G-M’s The Red Mill, a lavish Cosmopolitan production starring Marion Davies. Had he noticed, Buster Keaton would have appreciated the symmetry of having one film bookend the other, for The Red Mill, an “A” picture by any measure, was directed by Roscoe Arbuckle.

Keaton himself had brokered the assignment, his pal Roscoe having hit another dry spell after marrying actress Doris Deane, his longtime paramour, in May 1925. (Buster served as best man, Natalie matron of honor.) Early in 1926, while Battling Butler was in the works, he drove out to Davies’ Santa Monica beach house, took her aside, and pitched the idea.

“Marion sold the idea to [publisher William Randolph] Hearst [who founded Cosmopolitan to produce her pictures]. I think it helped that Hearst had never believed what his newspapers had printed about Roscoe during his trouble. Once I heard him say he had sold more newspapers with that story than he had on the sinking of the Lusitania.”

Arbuckle was announced to the trade as the director of The Red Mill in March 1926, and he and his wife and the Keatons took a drive north into Yosemite National Park in Roscoe’s new Lincoln phaeton to celebrate. The trip didn’t go well; they were waved past road repairs being made by convict labor and ran afoul of a state regulation prohibiting women from passing prison work camps. Barred from park roads for fourteen days, Keaton had to charter a train to get them and the car out of the valley. Davies, meanwhile, was wavering on her commitment to the source material, a 1906 Victor Herbert operetta that meant another costume picture tailored to Hearst’s tastes rather than the public’s. In the end, she went ahead with it, counting on Arbuckle’s comedy instincts to get them through it.

Freed from the tensions Peg Talmadge brought to the making of Sherlock Jr., Arbuckle ran a more relaxed and efficient set. Still, Hearst prevailed upon King Vidor, director of The Big Parade, to visit regularly and keep an eye on Arbuckle’s progress. “But then they didn’t like the rushes,” said Marion Davies, “so they put George Hill on. Then they didn’t like George Hill’s work, and they put Eddie Mannix on. And Eddie got fired. That picture had so many directors I can’t remember all their names.” When filming stretched into a third month, Vidor and unit manager Ulrich Busch were brought on to shoot crowd scenes and minor interiors, reportedly leaving the few remaining scenes with Marion Davies to Arbuckle.

The results weren’t well received. Variety’s Sid Silverman memorably described The Red Mill as “an idiotic screen morsel substantiating the contention that the average intellect of a picture audience parallels an eleven or thirteen year-old youngster.” He added: “The Capitol is evidently suffering a reaction from Flesh and the Devil. That one lingered four weeks and was doing well enough to have remained another. Then came The General and now The Red Mill….The adults were up to the neck with boredom, and the morale won’t be any different no matter where this one plays.”

Prior to the release of The Red Mill, Arbuckle landed another assignment, capably directing Eddie Cantor in Special Delivery for Famous Players. Yet nothing further came of these two, and with the completion of the Cantor picture, he returned to vaudeville and, briefly, enjoyed a run on Broadway in a revival of Baby Mine with Humphrey Bogart and Lee Patrick in support.

As Buster Keaton approached his second picture for United Artists, he was faced with an almost complete shift in his team of writers. Paul Gerard Smith quarreled with him in Cottage Grove and returned to stage work in New York City. Clyde Bruckman went back to Monty Banks, for whom he would direct the comedian’s next feature. Al Boasberg asked for his release to take a vacation and get married. And Charles Smith moved on, writing Naughty Nanette for Viola Dana, among others. With Lou Anger in New York and Joe Schenck assuming even greater responsibilities with the November 1926 death of UA president Hiram Abrams, Keaton must have felt somewhat adrift, even as he had an idea for his next movie at the ready.

College pictures were in vogue. Mostly comedies or light romances, they radiated youthful energy and beauty, and served as sparkling showcases for new contract talent. More Americans than ever were attending colleges and universities, enrollment having risen 84 percent over the previous decade. Recent film hits included The Plastic Age, Brown of Harvard, The Campus Flirt, and The Quarterback. A series of two-reelers for Universal, The Collegians, was so popular it was extended into a second season. Most successful of all, of course, was The Freshman, which ideally suited Harold Lloyd’s eager beaver and staked out territory to which Chaplin could never aspire. For Keaton, a college setting offered myriad opportunities for physical comedy, athletics alone suiting him and his unique style of slapstick better than any of his contemporaries. Moreover, a Keaton picture set on a college campus would virtually write itself.

With The General essentially finished, Keaton began assembling a new staff to help flesh out a story. In no particular order, he picked up Carl Harbaugh, a journeyman writer with a range of credits, most recently with Hal Roach and Mack Sennett, and Bryan Foy, one of the Seven Little Foys of vaudeville fame who occasionally wrote and directed short comedies. Neither man was of much use to him, particularly Harbaugh.

“He didn’t write nothing,” Keaton complained. “He was one of the most useless men I ever had on the scenario department. He wasn’t a good gagman; he wasn’t a good title writer; he wasn’t a good story constructionist.”

Foy, who would go on to become a producer at Warner Bros., couldn’t have been much better. Still, as Keaton reasoned, “we had to put somebody’s name up that wrote ’em.”

Around the same time, he took on a director named James W. Horne, whose essential background was in making serials, initially for Kalem, later on a freelance basis. Horne was skilled at grinding out footage on a tight schedule, a valuable quality in the mechanical world of chapter plays, where a single project might equal the length of three or four normal features, but of little advantage to Keaton, who adhered to only the vaguest of schedules.

A clash between Keaton and Horne was inevitable, given the instinctive way Keaton developed and refined a scene. Keaton, in fact, found Horne to be “absolutely useless” on the picture, which soon acquired the utilitarian title College. “Harry Brand got me to use him for College.[*4] He hadn’t done very many important—no important—pictures that I remember, only some quickies and incidental things. I don’t know why [I used him], as I did practically [all of] College anyway. It didn’t make any difference to me.”

Lacking the support of a Jean Havez or a Clyde Bruckman—his two favorite collaborators—Keaton was effectively left to write and direct College by himself. In casting the picture, he knew he would need certain types no matter which direction the story took—the mother, the girlfriend, the rival, the college dean. For the girl, he settled on Anne Cornwall, a no-nonsense brunette who had been in pictures almost as long as he had, and who, at four eleven, was even an inch shorter than Virginia Fox. The part of the mother went to veteran stage and screen actress Florence Turner, arguably the movies’ first genuine star, while Snitz Edwards returned to the Keaton studio in the role of the dean. For Jeff Brown, his student rival, Keaton wanted someone who was physically imposing as well as good-looking, and chose Harold Goodwin, who was six two, after a perfunctory interview.

“I was called over to the studio,” the actor remembered, “and they said, ‘This is Mr. Keaton.’ He says, ‘Do you play ball?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I used to play at school.’ He says, ‘You’ll do.’ ”

Filming began in Los Angeles on January 14, 1927, with the original UCLA campus on Vermont Avenue standing in for the fictional Clayton College. Buster is Ronald, a bookish high school student who is proclaimed “our most brilliant scholar” as he receives his diploma and an honor medal. He is then invited to speak to the graduating class on the subject of “The Curse of Athletics” while his cheap woolen suit shrinks from having been drenched in a rainstorm. Outside, Mary Haynes (Cornwall) angrily delivers a lecture of her own. “Your speech was ridiculous,” she tells him, rain pouring on them both. “Anyone prefers an athlete to a weak-knee’d teachers’ pet.” She then delivers the traditional Keaton ultimatum that typically sets the action in motion at the end of the first reel: “When you change your mind about athletics, then I’ll change my mind about you.”

The rest of the picture is Ronald attempting to prove himself to her, tackling with astounding ineptitude almost every athletic endeavor the school can offer—baseball, track, shot put, discus, javelin throw, high jump, sprint hurdles, hammer throw, pole vault. James Horne was on hand throughout these episodes, most of which were staged on the USC campus or nearby in the Memorial Coliseum, but he really couldn’t contribute as Keaton painstakingly worked out the physical business suggested by the trappings and traditions of each event.

“Jimmy Horne—he was probably one of the worst directors in the business,” said Harold Goodwin, a veteran of more than fifty films by then, “but Buster had him standing by to direct scenes that didn’t mean much. Buster directed most of the show.”

While Horne never got in the way, the innocuous Harry Brand was suddenly eager to show Joe Schenck he was up to the job of managing the studio. Brand was always an easygoing sort, famous for his wisecracks and practical jokes. “But once he was on the job he suddenly turned serious,” said Keaton. “He was grim. He was watching the dailies—how much is spent on this, how much is spent on that? He worries, he frets, he begins losing sleep. He felt he had to do something, like a guy who has to tear down a car that’s running perfectly.”

Harold Goodwin recounted a day Brand felt compelled to assert himself: “Well, Snitz Edwards, who played the college dean, was getting $500 a week. I think I was getting $300. Grant Withers was on it and he was getting $200. None of us made much money, but it was a lot of money in those days. And we had one closed stage, and we had an open stage, and we played ball, softball, on this open stage. So, Harry Brand wanted to show his authority and he said to Buster, ‘I’d like to get Snitz Edwards off salary.’ Buster didn’t say a word, he just went to the crew and said, ‘Come on, we’re going to play ball for two or three days.’ And we did. Harry Brand never came back on the set again.”

College was a relatively simple picture to shoot—no big set pieces or mechanical effects—but a lot of the action was set out of doors, and it was filmed during the rainy season in Southern California. The opening scenes with Florence Turner were staged in Glendale in a driving rain, but once the interiors had all been made there was nowhere else to go. As in the old days, Keaton would retreat to his dressing room and play cards with the crew, but he typically got itchy after a day or two.

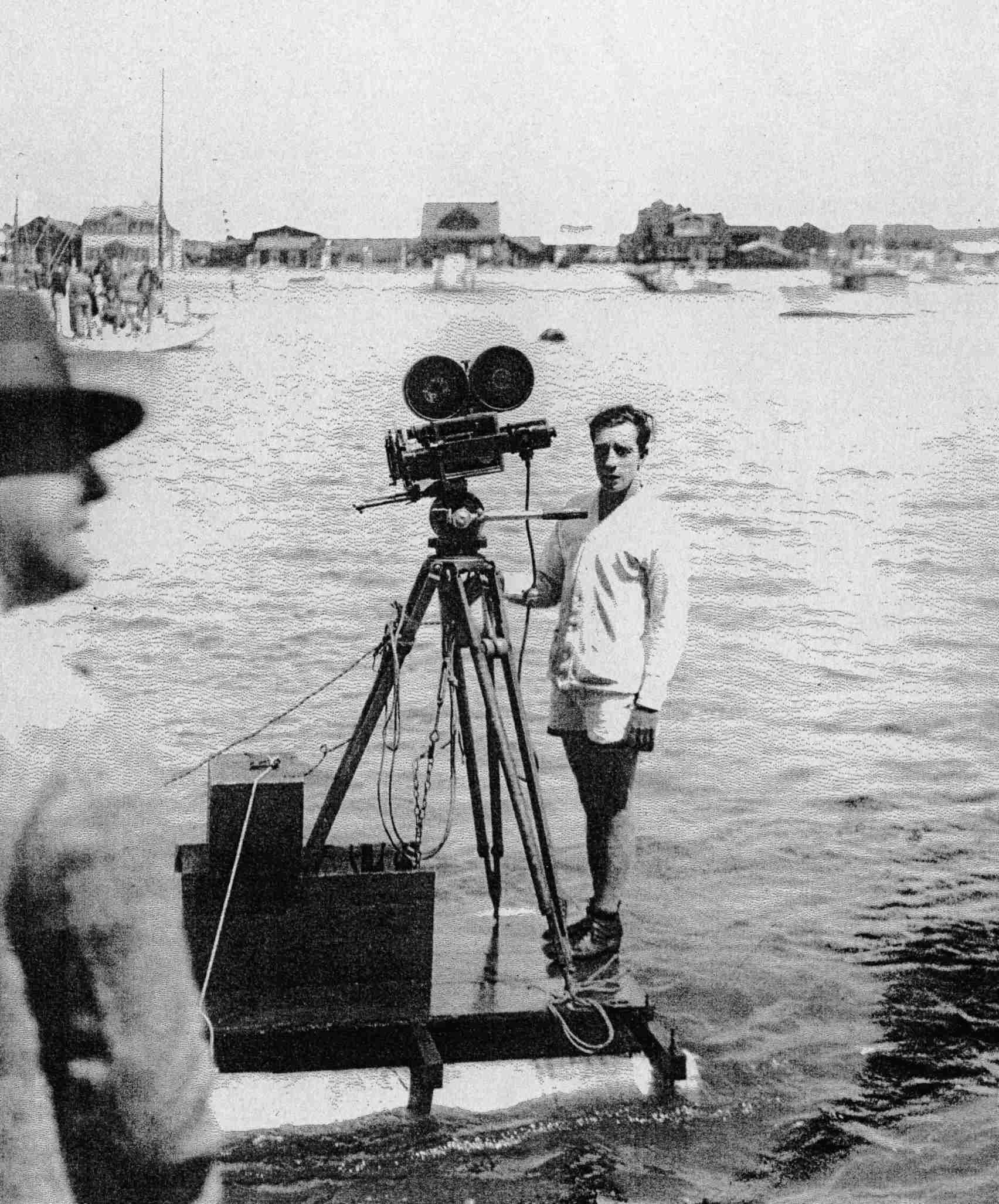

Filming College on the water at Newport Bay, April 1927.

Keaton called on his father to round up a few faces for the new picture. Joe was tickled with the assignment, because he knew a lot of old-timers who would be grateful for a few days’ work. He remembered all their names, of course, but didn’t have their addresses at hand. So he turned his car over to a guy at the Continental Hotel with instructions to hit all the booking offices and check the registers for “the boys.” The result was that fourteen semi-retireds got much-needed jobs. About the same time, a wistful item on “fine old couples” appeared in Nellie Revell’s column in Variety. She lamented that Harry and Rose Langdon were no longer together, Harry, now a big star, having taken up residence at the Hollywood Athletic Club. “But what caused a really big lump to rise in my throat was the news that Joe and Myra Keaton are no longer sharing the same address. Myra, Louise, and Jingles occupy the handsome home provided by Buster, but Joe lives at a hotel. It is especially poignant when one thinks that now, after so many years of shared vicissitudes, they could be living together with everything they want. And that they are not doing so. But Joe hasn’t had a drink for four years.”

The highlight of College was to be an intramural rowing competition in which Ronald, as the team’s unlikely coxswain, manages to save the day when the rudder comes off the boat during the big race. Keaton selected Newport Beach, fifty miles southeast of the studio, as the location for the sequence, having previously filmed there for The Scarecrow, The Boat, and Sherlock Jr. Specifically, Newport Bay would be the scene of the race, with the landmark Balboa Pavilion, slightly altered, providing a festive backdrop. Keaton gave Harry Brand the job of recruiting sixteen experienced oarsmen, all to work under the direction of Ben Wallis, former coach of the University of California racing crew, while Gabe Gabourie was tasked with rounding up—or having fabricated—six racing shells for the competition. A company of forty-five arrived at Balboa on March 24, some putting up at the Southern Seas Club on the bay front, which would also be feeding the crew, while Buster, Nat, and sister Dutch secured a cottage for the duration of the shoot. Lack of sunshine delayed the start of filming several days, and production stretched into the middle of April, as working on water was always slow going.

Among those Keaton had with him on location was actor William Collier, Jr., a close friend who was also known as Buster, and who was godfather to Keaton’s older son. “I worked with Keaton on—not all of his stunts, but a few of his stunts each year that were dangerous,” Collier recalled, “and he relied upon me because he wanted to be sure nobody was kidding around. There were always some comedians off screen, you know. And he relied upon me to calm everything down and to get it done, get it right, get him alive….He’d have a water scene, and there were some very dangerous tides. [It was] very badly organized for safety. Nobody else seemed to care about anything but having a good time.”

Ronald has triumphed, having tied the rudder to his waist and lowered himself into the water in order to steer the craft to victory. He’s alone in the crew’s bathhouse when the phone on the wall rings and it’s Mary pleading for help. A jealous Jeff, having been expelled, has locked himself in her dorm room so that she’ll be expelled along with him. The threat of rape hangs in the air, and the dire circumstances bring the true athlete out in Ronald as he races to her rescue, clearing hedge after hedge and literally pole-vaulting into her room through a second-story window.

For this shot, Keaton faced a dilemma: shut down production in order to master the feat himself, or break a career-long policy of never using a stuntman. For a comedian, this wasn’t a matter of pride or machismo so much as practicality—the professional men and women who did stunts for the screen were able enough but, generally speaking, they weren’t funny. “We knew from bitter experience in the old days that stuntmen don’t get you laughs. That’s why we did most of them ourselves.” Thinking it over, Keaton opted to keep the picture moving and sent for USC’s Lee Barnes, Olympic gold medalist in the 1924 Paris games, to do the stunt instead.

“I could not do the scene myself because I’m no pole vaulter and I didn’t want to spend months in training to do the stunt myself.”

Once inside the room, face-to-face with Jeff, Ronald furiously starts pelting his adversary with whatever is at hand—cups and dishes, books, a bust he sends crashing through a window. It’s a replay of the fight scene from Battling Butler, the character seething with anger, the violence desperate and ragged. As real and as unstaged as it seems, Harold Goodwin remembered a lot of trial and error in getting it right. “We’d make five attempts at the thing and then put a number on it. It was in the college dormitory and Buster’s supposed to kick this ball up against the door and it’s supposed to come back and hit me in the head. Well, we did that about seventy-five times, and then we abandoned that. Then, in the end, when he catches me in the room with a girl, the ball rolls through the window. I was supposed to start throwing things at him, and he takes this canoe paddle and he’s supposed to bat this thing back and hit me, and I go out the window. Well now, he could have done it in cuts, but he wanted you to see what the hell is happening. Well, we finally had to abandon that. Finally, Buster said, ‘If one comes close, just step back and crawl through the window.’ So that’s the way we got it.”

College finished in mid-May after four months before the cameras, and Keaton launched into preparations for his next picture without a break. The impetus for the film that became Steamboat Bill, Jr. came from director Charles F. “Chuck” Reisner, a monologist and song-and-dance man in vaudeville who made the leap to pictures by way of the scenario department at Keystone. In 1918 he joined Chaplin, first as an actor, then as gagman and assistant director, eventually directing Syd Chaplin in five of his feature comedies, including The Better ’Ole (1926).

“Chuck’s story,” as Keaton remembered it, “opened with a rugged old Mississippi steamboat captain reading a letter from his wife. They had a quarrel twenty years before, just after their only child was born. She returned with the baby to her hometown in New England. The letter explains that their baby, now a fully-grown man, is on his way to see his father for the first time. He will arrive by train on Sunday and will wear a white carnation so his father will recognize him. But the Sunday I arrive is Mother’s Day, and every man on the train is wearing a white carnation in his buttonhole. Hopefully, my father, Steamboat Bill, approaches one muscular youth after another. But he doesn’t find me until the train pulls out because I got off the train on the wrong side. He takes one look at me and groans. I have on a beret and plus fours. I have a ukulele under my arm and a ‘baseball moustache,’ so called because it has nine hairs on each side….With this for a start, all we needed to get the story rolling and churning was a wealthy menace with a pretty daughter.”

For the role of the father, William Canfield, a.k.a. Steamboat Bill, Keaton recruited Ernest Torrence, six foot four, a star heavy in pictures with the face of a battered prizefighter. Torrence’s roles ranged from the king of the beggars in The Hunchback of Notre Dame to Captain Hook in Peter Pan. The wealthy menace, in the person of actor Tom McGuire, became a rival steamboat owner, J. J. King, president of the River Junction Bank and proprietor of the local hotel. (“This floating palace should put an end to that ‘thing’ Steamboat Bill is running,” he boasts.) And Keaton discovered actress Marion Byron, all of seventeen, in the Hollywood Music Box Revue, where she played a memorable bit as a child in a sketch with Fannie Brice.

“Miss Byron has never worked before a camera,” he said, “but she is a human dynamo and just the right height. In fact, she comes about even with my ears—when she has on high-heeled shoes.”

Keaton collaborated on the story with Reisner, who was engaged to direct the picture, while cutting College for a July release. Harry Brand, meanwhile, ever eager to justify his existence, appointed Carl Harbaugh, presumably serving out a year’s contract, chief of the studio’s scenario department “in recognition of his work on the latest Keaton production.” By July, Keaton and Reisner were far enough along to make a scouting trip to Sacramento, the state capital, where the winding Sacramento River had previously served as the Yangtze for a Richard Dix epic titled Shanghai Bound and the Volga for Cecil B. DeMille’s The Volga Boatman. Earlier still, portions of James Cruze’s The Pony Express were filmed there. Accompanied by Brand, Harbaugh, and Gabourie, they cruised the river, confirming it would stand in nicely for the Mississippi, with room to construct the entire town of River Junction on the west bank near its confluence with the American River.

Within days, a huge exterior set was under construction, the King Hotel and thirty-three other buildings lining two fully macadamized boulevards complete with concrete sidewalks, outdoor lighting, and a pair of wharves jutting out into the water. At a cost of around $50,000, River Junction would serve as the backdrop for most of the action in Steamboat Bill, Jr., and then, in a spectacular climax, it would be destroyed by torrential rains and a devastating flood. With typical efficiency, Gabourie and his on-site foreman, Lloyd Brierley, along with 150 local workers and craftsmen, were aiming to have it all fabricated within a couple of weeks so that filming could begin there on July 20. Then portions of the town would be reconstructed a few miles away for the flood scenes in the Sacramento’s slow-moving waters. In all, Brierley estimated, 200,000 board feet of lumber would go into the job.

With the town taking shape, a call went out for hundreds of extras, causing the local chamber of commerce to process more than two thousand applicants in the space of a couple of days. A reporter from The Sacramento Bee observed “pretty young girls—lots of them—lured by the chance to appear before the camera. There were matrons and mothers with babes in arms, youths, laboring men, well-dressed men, stout men and women and lean men and women. There were a few Negroes too, for these also will be required.” The chamber was informed that as many as a thousand people would be needed for some scenes “and that well-dressed men and women and girls and boys are especially in demand.” The Keaton company was expected to pay out an estimated $100,000 in wages in just six weeks.

Production started on July 18 when the company filmed Willie’s arrival from Boston at the village of Freeport, on the eastern bank of the Sacramento. The old station had been scrubbed and painted for the occasion, and a train from the Southern Pacific, loaded with a hundred extras, was repainted to represent the fictional Southern Railroad. The making of exteriors at River Junction began two days later with the dedication of King’s gleaming new boat, hundreds of spectators and celebrants crowding around, while Steamboat Bill watches sourly from the bridge of the aging Stonewall Jackson.

“We’re having a wonderful time,” Keaton told Kay Lane, a feature writer for The Sacramento Union. “I always have a good time here. Oh yes, I’ve been here several times before. That river is great to fish in. We used to start out of here on hunting trips up in the mountains. I’m going again, too, if I ever get time away from the grind.”

Joe Keaton, who came up ahead of the company to get away from the city, seconded his son’s assessment of the fishing. “I’ve fished in that river many times,” he said. “I’ve caught lots of bass in there. I fished in that river when the Panic was on and food was scarce.”

Leaving the subject of fishing to the Keatons, Dev Jennings praised the river as a photographic subject. “The light here is great, strong, good light,” he said. “The color of the river is okay. We’re using panchromatic stock, [which] photographs color backgrounds better than ordinary film. This is a good place to shoot pictures.”

Buster added: “There’s only one thing wrong with your town. I’ve had a terrible time rounding up bridge players. If you have anybody over there on the Union that plays bridge, bring ’em around this evening, or any evening.”

Work had scarcely begun when a distraction presented itself in the form of a plagiarism suit filed in federal court against Buster Keaton Productions by the widow of William Pittenger, author of The Great Locomotive Chase. In a statement to The Sacramento Bee, Keaton dismissed the suit as groundless. “We obtained our source material from the United States War Department records of the Civil War,” he said, “and did not use Pittenger’s story. He also told the story as a participant in the incident, while we took an entirely different point of view. Investigation has disclosed that the story of the same incident has been written by at least two other participants in the adventure entirely independent of Pittenger’s story. We have as much right to use the incident as the basis of a story as two separate authors have the same right to use the World War as plots for stories.”

Chuck Reisner turned out to be a good match for Keaton as director of Steamboat Bill, Jr. Eight years his senior, Reisner took to referring to his star as “little Buster,” his memories of The Three Keatons from his own vaudeville years being so indelible. Reisner traveled to Sacramento with his wife, Miriam, and son, Dean, age nine, who was off from school for the summer.

“They had this great old riverboat,” Dean Reisner remembered, “and we all used to fish off the side of it all the time—catching catfish. I remember Buster took a pole one day, and all of a sudden he caught the goddamnedst fish you ever saw. He was fighting it and passing the pole over people and saying, ‘Excuse me.’ And finally he pulled it up and it was a prop fish that he had.”

With Reisner on the job, Keaton was able to make himself available to the press in a way he couldn’t during the making of The General or College. “I’m sort of a long-lost son,” he said in giving a reporter for the Bee an idea of what the picture was about, “and Ernest is the dad. In fact, we contemplated naming the picture The Long-Lost Son, although at present time we have the title Steamboat Bill. That’s the interesting thing about comedies. You never can tell how they are going to turn out or what they will be named until after they have been finished. Comedies are different from dramas. The detail has to be worked out as the filming of the story progresses. When we get stuck we employ the ‘huddle system.’ What’s that? Why that’s what we were doing just a moment ago. We all get our heads together like a bunch of college boys taking football signals. Then we figure out what will come next—whether we will burn up the town or save the heroine.”

As was her habit, Natalie Keaton was on location with her husband, but she kept such a low profile she was scarcely noticed. A woman from the Bee pursued her for several days, trying to land an interview, but never seemed to be able to get her attention. Finally, Louise Keaton, there to act as script girl and stunt double for Marion Byron, stepped in. Described as “a mannish young person clad in a bathing suit, overalls, and eye-shades,” Louise explained that Mrs. Keaton was painfully shy around reporters but that she could and would respond for her: “Although Mrs. Keaton finds Sacramento most charming in every way, most of her thoughts are with her two small boys at home. They are Joseph, aged five, a young Buster, and Bobby, three, who resembles the Talmadge family, of which Mrs. Keaton is the youngest [sic] sister.”

Buster seemed to enjoy Nat’s presence on the set, and she was predictably there, sitting and knitting, every morning at eight thirty. She was also there one afternoon when, while playing a local ball team, Buster removed his catcher’s mask in the eighth inning and a few minutes later was pasted by a fast ball, breaking his nose. Still, he was able to keep working, and by August the set was inundated with sightseers from all parts of central California, so many, in fact, they were forced to rope off the camera area.

College opened at the Metropolitan Theatre in Los Angeles on July 29, drawing a tepid response from Marquis Busby in the Times: “While College will undoubtedly prove a more popular vehicle for the frozen-faced comedian than The General, I am not so sure it is a better picture. The General at least had some thrills, but College is not particularly exciting….With Buster Keaton the picture passes as mildly entertaining, without him it would be terrible.” College, paired with madcap bandleader Rube Wolf and a strong Fanchon and Marco prologue, grossed nearly $30,000 for the week, an exceptional performance considering there was a seasonal spell of hot weather. Keaton was still on location in Sacramento when the film came to the Senator Theatre in mid-August, and he took his entire company to see it. Up came the opening title, which then dissolved into the following:

Directed by

JAMES W. HORNE

Story by

CARL HARBAUGH and BRYAN FOY

Supervised by

HARRY BRAND

“I all but jumped out of my seat,” he said. “It had gone into the prints after I had okayed the sample. It had been done quietly and with Schenck’s permission. The prints—two hundred and fifty of them—were all distributed. The thing couldn’t be changed.” He was still fuming over Harry Brand’s interference when Brand, who insisted on being present on location, objected to Willie being sent into a haberdasher’s store for some “working clothes for the boat,” only to emerge in a perfectly tailored naval uniform and cap rather than a broadly funny outfit one would naturally expect in a comedy. Chuck Reisner tried to explain:

“Prior to outfitting Keaton in that uniform we had built an unsightly river dock, an old side-wheeler of Civil War vintage, an aging captain, rough, gruff, and tough, and his motley, unkempt, hard-boiled crew completing the picture. And that scene was built and cast that way in order to realize fully upon the contrast Buster would create when he arrived there. But my analysis of the possibility of more and bigger laughs when Buster arrived at that unsightly boat and dock in a neat uniform got me nowhere. The only thing that saved the situation was the fact that we would have to take time off to have a comedy uniform made, and that meant a half day or more lost and an added production cost of probably five thousand dollars or more.”

With the remade titles for College, the same Harry Brand managed to imply to the world that Buster Keaton was under his personal supervision.

“Now perhaps it sounds like conceit on my part,” Keaton allowed, rehashing the incident twenty-five years later. “But besides my own feelings, there were two things. One was the question of interference. A bad thing to get started. The other thing was, the public was already beginning to laugh at this stupid supervisor deal, which had then been going on in Hollywood for about six months. ‘Supervisor’ was only a job maker, a nothing job, just a title—but it did get a guy’s name on the screen. Anger never bothered with screen credit. He knew his job and did it.”

Rather than rail at Brand or go off and play baseball, Keaton reserved his ire for Joe Schenck. A week later, Schenck arrived in Sacramento, where he toured the River Junction set and huddled privately with his star. Keaton complained about the credit for Brand and the fact that it had been added behind his back. Schenck countered that supervisors were part of an emerging system in the industry, and that he had started giving twenty-eight-year-old John Considine, Jr., a supervisor credit on many of his own productions.

Keaton was unmoved. “There’ll be no more supervisors in pictures Buster Keaton makes,” he declared. And that was when Schenck told him that Buster Keaton wasn’t going to be making any more pictures.