23

Diggin’ Up Material

WITH IN THE GOOD OLD SUMMERTIME awaiting release, the only film work Buster Keaton could muster was a one-day cameo at Paramount. The picture was titled Sunset Boulevard, and it starred Gloria Swanson as an aging movie queen who keeps a struggling young screenwriter played by William Holden. The scene in the script was of a card game taking place inside Swanson’s run-down mansion, depicting her “and three friends—three actors of her period. They sit erect and play with grim seriousness.” In his voice-over narration, Holden describes them as “dim figures you may still remember from the silent days. I used to think of them as her Wax Works.”

Producer Charles Brackett had no trouble securing Keaton and H. B. Warner for the picture, but was turned down “with hauteur” by Theda Bara and Jetta Goudal. When director Billy Wilder shot the scene on May 3, 1949, the foursome consisted of Swanson, Warner, Keaton, and Swedish-born Anna Q. Nilsson, a major star in the twenties who had lately been doing extra work.

“She looked well, by the way, the ghost of a beauty,” Brackett recorded in his diary. “H. B. Warner and Buster Keaton were somber relics of the past. And Gloria, looking absolutely sparkling, full of the sense that she’d beaten the years far better than they, made a great fourth.” As he took his seat at the table, Keaton was heard to mutter, “Wax Works is right,” sending the others into howls of laughter.

Keaton returned to the stage in 1949, embarking on his first summer stock tour since The Gorilla in 1941. The play this time would be George Abbott’s Broadway hit Three Men on a Horse, a perennial favorite on the straw-hat circuit but one that would burden him with dialogue. As they had eight years earlier, Buster and Eleanor made the drive east on their own, this time planning a two-day stopover in Muskegon to get some fishing in. Having not been there in sixteen years, he was astonished at all the growth.

On the set of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard: Anna Q. Nilsson, Gloria Swanson, Keaton, William Holden, Erich von Stroheim, and H. B. Warner.

“I thought I was in the wrong place,” he said. “One-way streets with traffic lights had me confused. Back thirty-five years ago, there wasn’t much traffic in Muskegon and there were only a few policemen and I knew them all. Now there’s traffic all over, and everywhere I look there’s a policeman.”

His first act upon arrival was to head for Pascoe’s, where he introduced Eleanor to the wonders of fried perch. “Most people don’t know how to cook perch,” he once averred. “You have to skin ’em, roll ’em in half cornmeal and half flour, and fry ’em in half butter and half lard.” That day, he sensed that Pascoe’s had been short-listed for extinction, the founder, Frank “Bullhead” Pascoe, having sold the place during the war.

“There was a young man there who never heard of him or me or anybody else,” remembered Eleanor. “It was about 3 p.m. and he had to have that perch. So the young man fixed it for him, and we sat on those front steps and ate it.”

Said Buster: “I must have eaten two dozen perch. They had the best fish I’ve ever eaten.”

With Frank Buxton in the Berkshire Playhouse production of Three Men on a Horse.

He and Eleanor stopped by the Muskegon Elks lodge, where Buster was a life member, and were rushed from one place to the next as word spread. (“They organized a parade of cars to take us on a tour.”) He fished off the dock at the Muskegon Yacht Club early the next morning and caught three pike. They visited Jingles Jungle, the old family homestead, and Keaton Court off Lakeshore Drive. And they were guests for dinner at the Edgewater home of Mr. and Mrs. E. W. Krueger, where Buster had held court back in 1933. It was a satisfying, and ultimately nostalgic, visit, doubtless tinged with regret for all the familiar figures who had passed from the scene—Big Joe Roberts; Max Gruber; Lex Neal; the Kruegers’ son, Kurt, who looked so much like Buster they were often mistaken for each other; his father, Joe, of course; Kate Millard (Mildred’s mother); and even Pascoe himself, who had died just prior to the Keatons’ arrival. Buster would come close to Muskegon again in the future, particularly to Detroit and Chicago, but never again would he make the familiar trip along U.S. Route 12 to the only hometown he had ever known. Too many ghosts now, too many to count.

Keaton’s tour of Three Men on a Horse began on June 20 in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where it inaugurated the Berkshire Playhouse’s eighteenth season. Actor-director Frank Buxton, who was spending the summer as a nineteen-year-old member of the resident company, recalled that Buster, despite a generous rehearsal period, was not letter-perfect that first night. “There were several moments when those of us on stage with him had to ad lib to get him back on track, with the audience none the wiser.” As Erwin Trowbridge, an unassuming man with a knack for picking racehorses, Keaton managed to work in some signature bits. “Billy Miles, the director, was smart enough to incorporate Buster’s shtick into the play because people expected it. Buster, of course, said, ‘I can do this here…’ And Billy said, ‘Certainly!’ ” Keaton put comedienne Janet Fox to bed as he had a drunken Dorothy Sebastian in Spite Marriage. “At another point Erwin gets mad at his meddlesome brother-in-law. To chase him off the stage, Buster ran from one side of the stage to the other, leaped in the air, landed on the back of his neck, and did one of his famous acrobatic twirls, finally landing on his feet.”

In three acts and two intervals the show ran long, not ending until half past eleven, causing Three Men on a Horse to draw a mixed notice in the Berkshire County Eagle. As Buxton remembered it though, they had a successful run: “We had great houses and great response.” The Keatons moved on to Hoboken in good spirits, but there were places where the Keaton name wasn’t the drawing card it had once been. As the tour wound down in Norwich, Connecticut, Keaton was wondering if he had a future in television, since the picture business seemingly had so little need for him.

Then something extraordinary happened. Life, in its issue of September 5, 1949, carried as its cover story an immense essay stretching over eighteen richly illustrated pages under the title “Comedy’s Greatest Era.” Its author, James Agee, former film critic for Time and The Nation, cast a broad net in researching this masterwork, then slowly narrowed his focus to the pioneering slapstick of Mack Sennett and the four comedians “who now began to apply their sharp individual talents to this newborn language.” These were Harold Lloyd, who “wore glasses, smiled a great deal, and looked like the sort of eager young man who might have quit divinity school to hustle brushes”; Harry Langdon, who “looked like an elderly baby and, at times, a baby dope fiend”; Charlie Chaplin, who “was the first man to give the silent language a soul”; and Keaton, who “carried a face as still and sad as a daguerreotype through some of the most preposterously ingenious and visually satisfying physical comedy ever invented.”

A vintage photo of Buster in costume, teetering on a diving board during the making of Hard Luck, dominated the initial two-page spread, and a section of the essay devoted to him carried the subtitle “THE GREAT STONE FACE.”

“Keaton worked strictly for laughs,” wrote Agee, “but his work came from so far inside a curious and original spirit that he achieved a great deal besides, especially in his feature-length comedies….He is the only major comedian who kept sentiment almost entirely out of his work, and he brought pure physical comedy to its greatest heights. Beneath his lack of emotion he was also uninsistently sardonic; deep below that, giving a disturbing tension and grandeur to the foolishness, for those who sensed it, there was in his comedy a freezing whisper not of pathos but of melancholia. With the humor, the craftsmanship, and the action there was often, besides, a fine, still, and sometimes dreamlike quality….Perhaps because ‘dry’ comedy is so much more rare and odd than ‘dry’ wit, there are people who never much cared for Keaton. Those who do cannot care mildly.”

Life enjoyed a weekly circulation of 5.2 million, and its publisher figured that it reached one in five Americans—meaning that “Comedy’s Greatest Era” put Keaton before an audience of nearly thirty million readers, enshrining him as part of comedy’s Mount Rushmore and making the case for his continued relevance. Moreover, of those with whom he was ranked, Keaton was the only one still ready and eager to work. Langdon was dead; Chaplin, beset by personal and political woes, was nearing the end of his time in the United States; and Lloyd was firmly retired, even as he considered ways of putting his old pictures in front of new audiences. The timing, for Keaton at least, could not have been better.

During the war, Jim Talmadge and his brother, Bob, served in the OSS as underwater demolition experts, based in Ceylon. Afterward, Jim settled in Pacific Palisades with his wife, Barbara, and their young family. Following the birth of their second boy in 1948, Norma, Jim’s aunt, said, “You won’t get out very much. I’ll buy you a little GE.”

When Jim’s father and stepmother came over, Buster was immediately transfixed. “We had one of the very first television sets in the whole area,” Jim said. “There was a ten-inch screen and a big console that weighed a ton, and my dad sat there and looked at that thing all afternoon.” Barbara finally had to force him to come to dinner.

“That,” Buster concluded, “is the coming mode of entertainment!”

Keaton had already settled on television as his new medium of choice when the appearance of “Comedy’s Greatest Era” reminded a broad swath of the public that he was a natural fit in a half-hour format. Immediately, he canceled plans to stop in New York to make some TV guest appearances and returned to California, where he huddled with Clyde Bruckman over the notion of making some “television shorts.” Leo Morrison instinctively went after a network deal, and soon arrived at a general understanding with CBS. Buster would go on the air December 14, 1949, with a weekly series called The Keaton Komedy Kollege. Ahead of that, he would soften up the audience with a guest shot on Ed Wynn’s network show, which would be promoted as his TV debut.[*1] The broadcast would originate live from the KTTV studios in Hollywood, with kinescope recordings of the show going to network stations in New York and Chicago, covering thirteen other eastern and midwestern markets. Keaton’s reserved demeanor could not be more unlike the flamboyance of the Perfect Fool. There were concerns the two wouldn’t mesh well, but in rehearsals Wynn wisely let Buster take the lead. On Thursday, December 9, at 9:00 p.m., Wynn took the stage in a sleigh pulled by a quartet of shapely young women and the show was on.

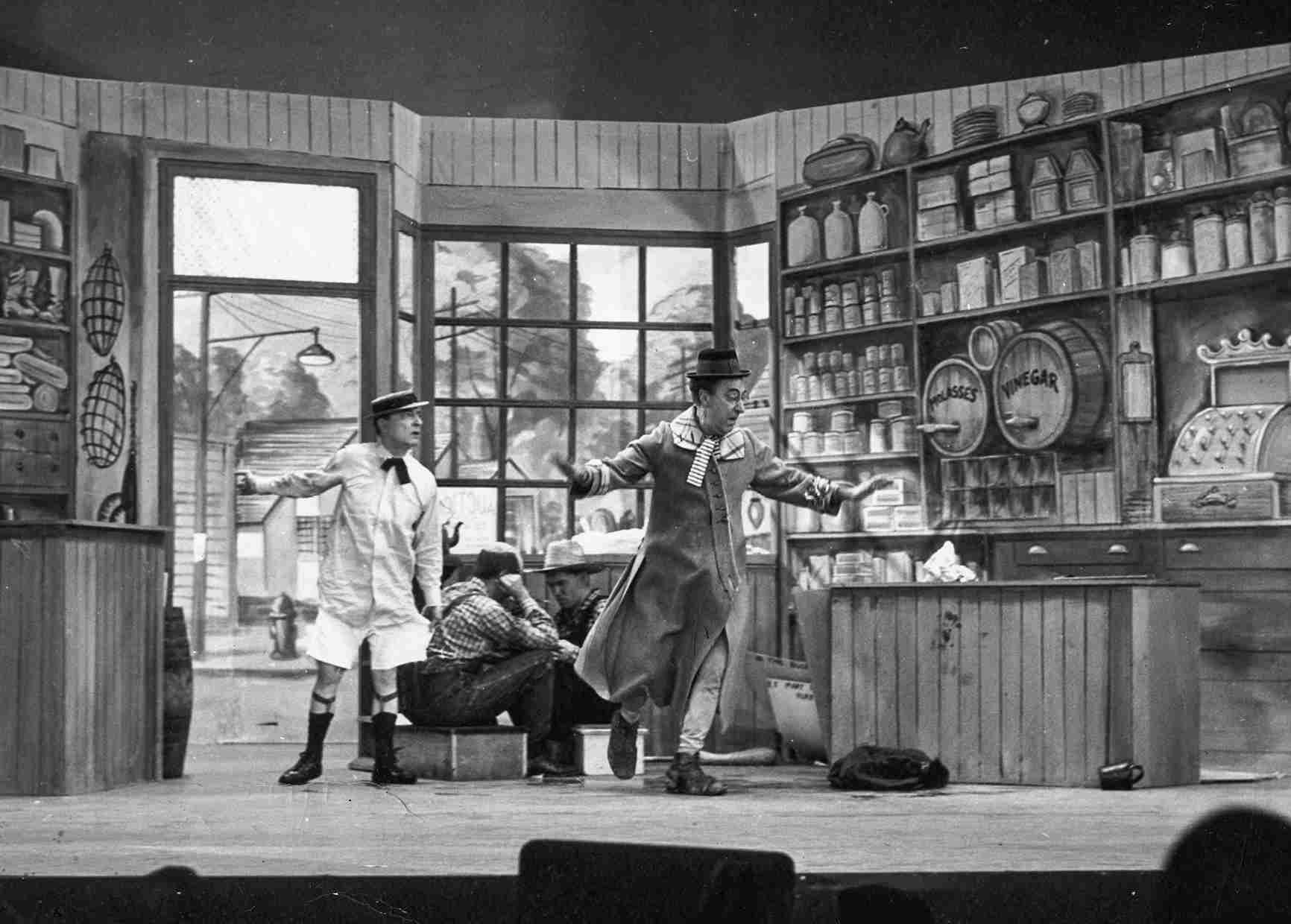

Keaton performing the “Butcher Boy” sketch on The Ed Wynn Show, which was widely believed at the time to be his TV debut.

The first half was typical of Ed Wynn’s brand of befuddled nonsense, while the second half, introduced by the host as “silent television,” recalled Keaton’s screen debut in The Butcher Boy some thirty-two years earlier. The scene was a general store. Keaton entered and adroitly picked a broom up off the floor with his foot. He mimed a line, then held up a card with the intertitle: GIVE ME 25 CENTS WORTH OF MOLASSES PLEASE. Wynn mimed an equally elaborate response and produced a card of his own: OKAY. The sketch was at once a send-up of silent-movie technique and an affectionate homage. The coin in the bucket, the molasses in the hat, the feet stuck to the floor—it was all there. The audience ate it up, delivering by far the biggest laughs of the evening. Wynn called Keaton back to take a bow, and the crowd gave him a rousing ovation.

“One of the most delightful gifts the televiewing public got for Christmas was Buster Keaton making his TV debut,” Larry Wolters proclaimed in the Chicago Tribune. “For all we knew this great comedian of the silent-film era might have been dead. Then he bobbed up without advance warning on the Ed Wynn show. For middle-aged persons it was sheer delight to again see this sad-faced little man with the wonderfully expressive eyes. And for generations of young Americans, who had missed him entirely in the pre-sound era, he proved just as funny….Not one word was spoken in the whole twelve-minute skit and yet it was one of the funniest bits that TV has offered to date.”

And there was something more, an embellishment to the skit that brought the biggest laugh of all. It wasn’t Keaton’s invention—he always gave his father the credit—but it was an idea that took the pratfall to the level of high art, a signature bit that would remain in the collective memory of an entire generation of viewers. As Wynn used a kettle of boiling water to loosen the grip of the molasses on his shoes, Buster hoisted one leg onto the counter, then the other, and seemingly paused in mid-air before plummeting to the floor—where the sticky stuff proceeded to saturate the seat of his pants.

“It looked like something off an animation board,” Keaton said, “the kind of thing an animator would draw—the four key positions—and leave the rest for in-betweeners to fill in.”

The public had seen it before—he did a crude, early version of it in Hollywood Revue of 1929 and reprised it in Three Men on a Horse—but now it advanced the action and enhanced the payoff. How he did it without breaking his neck was a mystery to many, but to Keaton himself the technique was elementary.

“When he did the ‘Butcher Boy’ fall,” Eleanor explained, “his feet were high enough that when he crashed, all his weight fell on the shoulders, which is where it should be. He’s got that heavy muscle structure [and it] acted like a pad. The spine, the tailbone—nothing like that ever touched the floor. You could get hurt. But if you held your breath and tensed the muscles, it doesn’t even knock the wind out of you.”

When no national sponsor came forward, the start of the new Keaton TV series was pushed back to December 22. Now simply titled The Buster Keaton Show, it became a production of KTTV, the CBS affiliate in Los Angeles, with plans to syndicate the show to other stations. With high hopes, management budgeted the series at $3,000 an episode, unprecedented for a sustaining program in a local market. The surrounding cast was assembled with actor-musician Leon Belasco, perennial heavy Ben Welden, blustery Dick Elliott, and radio’s Alan Reed, who would go on to fame as the voice of Fred Flintstone. Former child actor Philippe De Lacy signed on as director, with freelance producer Joe Parker pulling it all together.

The second revision of the script by Clyde Bruckman and actor-writer Henry Taylor was finalized on the day of broadcast. Advance press said Buster would speak just two words that night: “Ladies and…”

From the review in Daily Variety:

An old-timer came into his own last night over a new medium. And it looks like television has a new “must-see” program, very likely to become a permanent fixture. Buster Keaton is the old-timer and the new Buster Keaton Show is the vehicle. Keaton has lost none of his touch with the passing years. Little Sad-Face is still one of the really great pantomimists of the era, and the television camera proves a perfect medium to catch those mannerisms and expressions, if last night’s work was a criterion….Opening show was built around ad agency topper (Elliott) hiring players for a show for a macaroni sponsor. Keaton is hired as star, Reed as emcee, and Belasco as maestro. Ben Welden is a temperamental prop man. Keaton delivered his best pratfalls and twisted his magic face to the howls of studio audience as rehearsals on show got under way.

The Buster Keaton Show came off so well that the Studebaker Dealers of Los Angeles County signed on as sponsors commencing with the January 5 broadcast. Keaton was pleased. “One of the reasons I stopped making movies [back in the thirties] was because there were too many cooks in the kitchen,” he told United Press’ Alice Mosby. “In the old days only three of us made my movies. Any more people and it’s poison….Arbuckle, Lloyd, Chaplin, Langdon—all their pictures were made by only three men, too. It’s not that way today. On television I can go back to creating my own show. Only three of us are working on it.”

Despite the rosy outlook, the sixteen-week run of The Buster Keaton Show was roiled by departures and station politics. Alan Reed withdrew after four weeks due to “contractual differences,” producer Joe Parker left after “strong words” with management, writer Al Manheimer came in to replace him but lasted only a week, the show itself was moved ahead an hour on the program schedule and relocated to the El Patio Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard, Parker returned after the show limped along for five weeks without a producer, and the show’s proposed syndication plan never got off the ground. Through it all, Keaton struggled to come up with twenty-five minutes of weekly content.

“The biggest thing that any comedian has got in television is diggin’ up material,” he said. “I’ll give you an idea: It’s that I used to make eight two-reelers a year. Well, a two-reeler was a half-hour show. Well, now when television comes along, they want thirty-nine of those a year. Well, there’s only one way you can get material. I mean just hiring writers and gagmen don’t solve the problem. You’ve got to start repeating and stealing. Anything you can think of. Like, ‘Well, we did that three or four weeks ago in a drug store; the next time we’ll do it in a butcher shop.’ And we change the backgrounds for gags or steal gags right and left!”

Bruckman and his various collaborators—Taylor, Ben Perry, Elwood Ullman, Jay Sommers—did the best they could, but they could only hint at the physical stuff, the specifics of which generally fell to Keaton to work out. As to dialogue, it turned out the two words he spoke on the first show were about all he cared to say. “And on future shows I’ll kill dialogue whenever I can,” he vowed. “I don’t go out of my way to talk.”

In desperation, Keaton recruited Harold Goodwin as his writing partner. “They were paying the writers to write the stuff that we’d ignore,” Goodwin remembered. “There was one show where he gets his diploma [and] he’s a private detective. It was a funny show, and we wrote it over at Buster’s house—Buster, Eleanor and I. This was a pip. And when the writer came on to see his rehearsed show he said, ‘That’s a rewrite of a rewrite!’ ”

The final broadcast took place on April 6, 1950. “Buster got into this straitjacket. It was a haunted house thing….Buster’d had a little too much to drink, and he fell on the floor in the straitjacket and cut his head. We had to go right on with the show and rush him off stage. That was the last show we did.”

It wasn’t the end of the road—everyone agreed the show would return in the fall—but something had to be done about the weekly grind. “It’s the quickest way to Forest Lawn that I know of,” Keaton said. “Trying to dig up material for that weekly show. The first few are easy. Then it starts to get tough.”

A hopeful sign was KTTV’s ten-year lease of the Nassour Studios at Sunset and Van Ness, a small but modern independent movie studio suited for production of the kind of filmed programming needed for syndication.[*2] The deal was worked out by Norman Chandler, publisher of the Los Angeles Times, which owned 51 percent of the station to CBS’s 49 percent. The first two shows on the production docket at the new facility would be the second season of the Keaton series and Pantomime Quiz Time, which was already being seen via kinescope in New York. As if to underscore the importance of the show’s continuing, the March 13 issue of Life devoted three pages to a photo layout of Keaton at work, including a traditionally verboten shot of him breaking into a broad smile.

Keaton was still at liberty in June when he came across a funny hat he thought Ed Wynn would like for his collection and took it over to him at the CBS Playhouse.

“Where do you keep your stage wardrobe?” Wynn urgently wanted to know. He had no finish for the show that was to go on that night and needed Buster’s help. They had booked five silent comics to pose as the original Keystone Cops for a pie-throwing finale, but nothing his writing staff—which included Hal Kanter and Seaman Jacobs—came up with was working. As Keaton raced home, he considered how Wynn usually ended his show by coming out in a nightshirt and nightcap and getting into bed. That night, after Wynn had personally displayed the credits for what would be his final show of the season, Keaton appeared, unannounced, to say he had another credit: PIES BY HELMS BAKERY.

“What pies?” asked Wynn.

“The pies,” responded Buster, “that we’re going to teach you how to throw.”

The curtain behind Wynn and his bed rose to reveal all five cops with pies in their hands.

“All kiddin’ aside,” Keaton assured him, “there’s a science to pie throwing. There’s an art to it.” He called for a volunteer, and Hank Mann, the only member of the group who was legitimately one of the early Keystone Cops, stepped forward. Keaton proceeded to demonstrate “the slow burn,” a deliberate shove straight into his face. Next came Keystone veteran Chester Conklin, who received a “shot put,” fast and messy. Then Roscoe “Tiny” Ward, who never worked for Sennett but whose towering frame forced Keaton to back away ten or twelve feet so that it was “like a throw to second base.” Finally, Heinie Conklin—no relation to Chester—stepped forward as Buster coached Wynn into delivering “a walking thrust.” The payoff came when a man stepped into the line of fire and Wynn landed the pie squarely in the face of CBS Chairman William S. Paley (as impersonated by Hal Kanter). Though hastily assembled, Keaton’s four-minute segment inspired more laughter than the entire show that preceded it.

Later that month, plans were announced for the continuation of the Keaton series on 35mm film. Norman Chandler was driving the creation of a loose network of twenty stations owned by major newspapers. Production bids were being solicited from outside producers for the making of a pilot, which was to be filmed in July. Then Chandler changed course and formed a company of his own, Consolidated Television Productions, to produce the pilot at a reported cost of $25,000. Mal St. Clair was set to direct the show, with Clyde Bruckman in the role of writer-producer. KTTV, being controlled by the Times, which was in turn controlled by the Chandler family, gave Consolidated first refusal on all of the station’s shows that could be shot on film. Contracts between the station, the packagers, and Leo Morrison, representing Keaton, were signed on August 7, 1950.

Frustrated by all the delays, Keaton signed another week-to-week contract with M-G-M, specifically to consult on a new Red Skelton picture titled Excuse My Dust. He worked with director Roy Rowland and screenwriter George Wells to gag up specific scenes in the script and to help visualize a road race staged with antique cars. (Toward the end of the race, Skelton gets a sudden thought and tells actress Sally Forrest: “Throw out the tool box,” explaining that his gas mobile will go faster if it’s not carrying so much weight. She throws out tools, then gets the idea of throwing herself out too.) The Skelton job took fifteen days, and Keaton went off the Metro payroll for the final time on September 15.

The pilot for the filmed version of The Buster Keaton Show was shot in early October at the new KTTV studios. The setup had Buster working for a tyrannical boss in a sporting goods store. Ineptly, he attempts to wrap a fishing pole and assemble a tent, and manages to get himself challenged to a grudge match with two popular wrestlers of the day—Lord Jan Blears, a snobbish monocle-wearing Brit who invented the Oxford leg strangle, and George Scott, better known as the Great Scott, a Canadian grappler who wore his hair long and blond and bounded into the ring wearing plaid trunks. Frequently seen on TV, Blears and Scott made inexpensive guest stars as well as durable foils for a burlesque tag team match in which Killer Keaton and Sluggy Slugger (stuntman Harvey Parry) faced the two men with predictable results. With a pilot finally in the can, the Keatons left for New York, where a round of TV appearances awaited them.

On November 5, 1950, Buster was on Ed Sullivan’s Toast of the Town, the first of several guest shots he would make on the program. Sullivan, who was a New York newspaperman and Broadway columnist in Keaton’s heyday, was a genuine fan and wanted his viewers to be as excited as he.

“You know, back when I was a youngster, one of the great comics of show business was called Buster Keaton. Now your fathers and mothers will remember him—I know you youngsters won’t—but Keaton had a very unique style of comedy. In the first place, he was a poker face. (When I speak about a poker face, I feel that I’m in charge…) But on top of that, his pantomime, his understanding of comedy and his timing set him apart in what was then an infant industry, just as TV is now. So it’s with the greatest sense of pleasure that tonight—making not his TV debut because he was on Ed Wynn’s show out on the coast and he was a tremendous hit—a great sense of pleasure that I present him on this stage. And I want to call him out here before he goes on and have you meet him formally. And I want you to give him the biggest hand that’s ever been given to a great performer—Buster Keaton, come on out here! I want you to meet the folks!”

Keaton emerged, acknowledged the audience, and spoke a few words. Sullivan asked him what he was going to do. “Oh, I’m not goin’ to do anything,” he replied. “I’m goin’ fishin’.” Whereupon the curtains parted to reveal a small pond. He took his place on a platform and proceeded to fuss with his pole, his hook, and his bait, taking several hard falls into the water (and onto the floor) while progressively drenching himself. Keaton had previously done the sketch on TV in Los Angeles, where the pond was bigger and more realistic-looking. (In New York it looked more like a children’s wading pool.)

“Only when he toyed with a splinter, climaxing with his donning an enormous bandage which entangled his gear, was there some of the brilliance of the silent film comedies,” Variety commented. If the bit wasn’t particularly strong, at least it was new to most of the country, and it heralded his return to the public eye in a big way.

The following week, Keaton was the uncontested hit of the Sullivan show as he reprised the famous scene from Spite Marriage with Eleanor, perfectly limp, as the woman he tries to put to bed. Having cleared a contractual blackout period, he was on Garry Moore’s afternoon show the following day, Ed Wynn’s 4 Star Revue on Wednesday, and Stop the Music on Thursday.

Performing the Spite Marriage routine with Eleanor on Ed Sullivan’s Toast of the Town in 1950.

“I averaged two shows a week,” he said of their New York sojourn, “with the lowest pay $750 a shot (when rehearsal was necessary) and $2,000 a Sunday from Sullivan.” For his third Toast of the Town appearance, on December 10, he offered an atypical bit of pathos as a department store Santa laboriously donning his shabby costume in hopes of finding seasonal work.

“He was going crazy trying to write all these things all by himself and get it organized,” said Eleanor. “They’re sketches, one or two he repeated, but mostly he’s trying to work out sketches to do on these shows. There might have been a couple of interview things, but mostly it was sketch work on the show. And he had to do everything by himself, work with the prop man to get all the props ready, everything. So by the time we got down to December, he was a basket case. We finally left New York and got home Christmas Eve. He was exhausted. With good reason.”

As Keaton put it: “I became, I think, the year’s No. 1 guest star.”

The decision to put The Buster Keaton Show on 35mm film made it imperative to sell the series into other markets before going back into production. Norman Chandler and Consolidated president J. Bert Easley had covered the cost of the pilot but were unwilling to front the money to make another twelve shows when shooting on film added as much as $5,000 an episode to the budget. Twelve stations were lined up in November 1950, grouped as Publishers Television Syndicate, but capitalization of $1 million wasn’t finalized until February 1951. The first series to go before the cameras would be a quarter-hour children’s show, with a soap opera to follow and some religious fare for the Protestant Film Commission. Keaton and Bruckman went back to work, preparing scripts to be shot at the rate of one a week. The great advantage of the new arrangement would be a consistent level of picture quality, infinitely superior to kinescope. The big drawback: no studio audience.

Filming began in April 1951, with Bruckman serving as producer under an executive producer named Carl K. Hittleman, a writer whose résumé consisted almost entirely of cheap westerns. With no background in comedy, Hittleman nevertheless imposed himself on the writing process, pushing Bruckman aside. Things did not go well from the start. Harold Goodwin, who was in some of the live shows, was present for the shooting of the pilot with the two wrestlers.

“We shot that in one day, that whole show,” Goodwin remembered. “So then, after the show got a sponsor, Hittleman wanted us to make them all in one day. One day…and this is comedy, this is not just stuff where you stand and read dialogue. That caused a lot of trouble because we went into overtime. My God, we were working from eight o’clock in the morning until eleven or twelve o’clock at night. They were pretty bad.”

The British-born director, Arthur Hilton, had been an editor at Universal, where he cut the W. C. Fields comedies and was nominated for an Oscar for editing The Killers. Hilton knew how the shows were going to go together, but he was of little help to Keaton in the staging of gags.

“Buster knew the shows weren’t good,” said Goodwin. “And I was partly responsible for talking him into it…Clyde Bruckman and I…but Clyde was through. He’d lost his creativeness. We made some horrible things—some turkeys. Buster hated Carl Hittleman. He said, ‘I won’t work with him on the set.’ He just took a dislike to the guy, and this same fellow said to me: ‘Here’s a comic who’s been in show business forty-five years and doesn’t know why he’s funny.’ Now that was a pretty dumb statement.”

The filmed series burned through material at a worse rate than the live shows because it lacked the considerable advantage of an audience. “It didn’t look up to date,” said Keaton. “It just looked old-fashioned, but the same material done in front of a live audience….You’re looking at just a dead machine when you do it with just a silent camera.[*3] And the canned laughs are absolutely no good at all….But the live audience, that’s a different proposition. And the same material, I only need two-thirds of it—I can eliminate a third of the material—to do a half-hour show. Work it to a silent camera…all right, now do the same material to a live audience and I can throw one-third of that material away and save it for the next show…Their reaction will make you work to ’em, which you don’t do to a silent camera, but you do to an audience…They space it for you. When you spy a laugh is going to come up, you don’t hurt that laugh, you help build it. I slide right past it to a silent camera.”

The stories put Buster in the Wild West, in a time machine, in a haunted house, and in the army once again, but the physical comedy in which he had no peer was supplanted by labored verbal exchanges. An air of desperation crept into the proceedings, as if all they were really doing was just grinding film.

“They weren’t spending any money on them,” said Eleanor, “and they gave us a director and editor who didn’t do much but stand around. Buster and the script clerk were the ones who really made those shows. The script clerk was a dear lady who had been around for years and knew what she was doing.”

The second season of The Buster Keaton Show debuted in Los Angeles on May 9, 1951, while the series was still in production. Reaction varied; Walter Ames of the Los Angeles Times caught an advance screening of the pilot and thought it “one of the funniest shows on the airwaves.”

The detective episode, which was actually the first televised, was caught by Variety, which had a vastly different reaction: “These are the kind of film quickies that give Hollywood a bad name. For a town that aspires someday to be the television capital, this is a sorry trailer.”

The show was still well-enough regarded to attract a regional sponsor in the American Vitamin Association, which secured five stations in Ohio for the run of the series, and in Vanity Fair Tissues, which covered a run over WNAC in Boston. The show was also cleared for Pittsburgh, where it was sponsored by the Duquesne Brewing Company. By the last of June, The Buster Keaton Show was airing on seventeen stations.

Keaton no longer appeared to care. He turned in the final show of the series on June 2 and, ignoring plans for another set of thirteen, left the same day for an eight-week variety tour of Great Britain under contract to Stoll Theatres. With options, he and Eleanor would be gone for three months, time enough, he hoped, for Consolidated Television Productions to forget all about him. The tour began on June 18 in Leicester, with Buster and Eleanor doing the Spite Marriage scene that went over so well on the Sullivan show. Other stops were made at Chiswick, Wood Green, Manchester, Derby, Cardiff, Shepherd’s Bush, and Hackney.

Upon conclusion of the Stoll tour, Keaton was recruited by impresario Bernard Delfont for an old-timers’ show called Do You Remember? that carried him, and such British favorites as George Robey, Hetty King, and Wee Georgie Wood, through most of August. In Newcastle, Keaton faced a decision to remain with the thriving show—in which he was top billed—or to return to New York, where he had TV offers lined up, including another Toast of the Town. To Buster, it wasn’t a hard call.

“I could never get a hot meal,” he said of the provinces. “It was either too early or too late in every hotel I stayed at. I had cold sandwiches for ten weeks. And they never seem to have heard of room service.” And it irked him to be bunched in with the geriatric set when he was only in his mid-fifties. “It’s like walking on your own grave.”

Buster Keaton was once asked how it felt to get back into pictures under Charlie Chaplin’s direction. “Oh, old home week,” he said warmly. In December 1951, Chaplin sent for him to discuss a scene in his new film, a drama of the English music halls called Limelight. The two men embraced; there was always great affection between them.

“He seemed astonished at my appearance,” Keaton recalled. “Apparently he expected to see a physical and mental wreck.” Fresh from his tours of Britain and a round of guest shots in New York, the man before him was feeling rested and prosperous, hardly someone on his uppers who hadn’t worked in years.

“What have you been doing, Buster?” Chaplin asked. “You look in such fine shape.”

“Do you look at television, Charlie?”

The answer, of course, was no. Chaplin wouldn’t have one in the house. And he couldn’t understand how working in such a lowly medium would be of benefit to anyone. “But, Buster,” he pressed, “tell me, how do you manage to stay in such good shape? What makes you so spry?”

“Television.”

Abruptly, the subject got changed. “Now,” said Chaplin, “about this sequence we’re going to do together…”

Charlie Chaplin had abandoned his tramp character after The Great Dictator, released eleven years earlier. In the interim he made only a single feature, a sardonic comedy about a serial killer titled Monsieur Verdoux. James Agee considered it a masterpiece, but it had gone begging at the box office, Chaplin’s first commercial failure. And now, four years hence, he was preparing to spring a stark drama with comic interludes on a moviegoing public that had lost its taste for him. In the story, Chaplin’s character is Calvero, an aging comedian with a history of alcoholism. When he is discovered performing on the streets, he is offered a benefit performance, which he sees as a chance at a comeback. On the evening of the show, he does several of his classic routines to great acclaim. Then comes the encore, a two-hander with another old-timer, and together the pair manage to bring down the house.

Working with Charlie Chaplin during the filming of Limelight (1952).

“Charlie was debating throughout the picture,” said Jerry Epstein, one of Chaplin’s two assistants. “He knew he had to get someone for the part [of Calvero’s partner]. He kept seeing someone on the set who was Sydney Chaplin’s stand-in…and he kept saying, ‘That guy’s got something. I bet he can play it.’ But he wasn’t too certain.” They had been shooting for several weeks when Keaton’s name came up. “I think the production manager on the picture [Lonnie D’Orsa] suggested Buster Keaton, and Chaplin heard he was a little hard up at the time and said, ‘Yeah, bring him in.’ ”

Once Keaton was set, Chaplin sketched a wordless routine that, when typed, ran to slightly less than a page and a half. Much of what he envisioned amounted to business—Keaton’s elderly, nearsighted pianist struggling with a slippery stack of music, Chaplin’s rusty fiddler dealing with limbs that retract and have to be yanked back to length, piano wires that stubbornly refuse to be tuned and seemingly snap at will. It amounted to a scripted improvisation, something to serve as a starting point for two master pantomimists when they got on the set.

“That sequence was a very, very difficult sequence to do, the two of them together,” said Epstein. “Buster came on the first day wearing his Buster Keaton hat, ready to go, and Charlie took him aside and said, ‘Buster, this is not [that] kind of picture. We’re playing different parts now. We’re not playing the old thing.’ And he said, ‘Yes, Charlie, of course. Sure. Of course. Anything you want.’ [Which is] what was sweet about him. It was like his first picture. He had all this enthusiasm of starting in pictures again, and that was terribly endearing….The crew just loved it, seeing Keaton and Chaplin working together.”

Keaton joined the picture on December 22, playing a brief dialogue scene with Chaplin in Calvero’s dressing room. Others working that day included actress Claire Bloom, a Chaplin discovery making only her second appearance in a movie; Sydney Chaplin, Charlie’s son; and veteran actors Nigel Bruce and Norman Lloyd. The company broke for the Christmas holiday, and Keaton subsequently occupied the background in theater scenes shot on a standing set at the RKO-Pathé studios in Culver City.

“His reserve was extreme, as was his isolation,” wrote Claire Bloom. “He remained to himself on the set, until one day, to my astonishment, he took from his pocket a color postcard of a large Hollywood mansion and showed it to me. It was the sort of postcard that tourists pick up in Hollywood drugstores. In the friendliest, most intimate way, he explained to me that it had once been his home. That was it. He retreated back into silence and never addressed a word to me again.”

Keaton had been on the film twenty days, some of them on holiday, others on hold, when Chaplin was finally ready to shoot the routine at the core of the picture’s final act. Arrayed in antique formal wear, musty and ill-fitting, they determinedly take the stage, Buster stooped and plodding with thick glasses and moustache, leaves of music stuffed under his arm, Charlie a portly, grotesque figure with bow and instrument in hand. And even though Chaplin was ill with the flu, running a fever and dripping with perspiration, it took just two days to get the entire sequence in the can.

“There was this kind of unconscious communication that went on,” said Norman Lloyd. “Not much talk. They would look and do something, then do it again. No talk. No Stanislavsky. There was a kind of communication between them that was unspoken. But it happened as they would adjust the routine—maybe more music or maybe Charlie wanted to pull the pants up higher or whatever. But then—‘No, we’ll do it again.’ And Buster would keep adding stuff at the piano with having more music falling all over the place.”

The routine ends in applause and death, Calvero working himself into such a lather he tumbles off the edge of the stage and lands in a bass drum, from which he continues to play. They haul him up and carry him off, drum and all, to the laughs and the cheers of the audience. He has hurt his back, he thinks, but as he lies on a couch in his dressing room, the doctor determines he’s had a heart attack. While an ambulance is summoned, he asks to be carried to the wings to watch the performance of a ballerina he’s mentored. And there he dies. As the body is covered with a sheet, the camera pulls back to include those surrounding him, principally Keaton, Sydney Chaplin, Norman Lloyd, and Nigel Bruce. It continues out onto the stage where Claire Bloom, in mid-performance, twirls into the shot.

It was a deceptively complicated movement that momentarily summoned the filmmaker in Keaton. “The camera,” said Lloyd, “was on Charlie—centered on him—and, as we were going backwards, with no dialogue, just music, I heard a voice, very quiet, just above a whisper, saying, ‘It’s okay, Charlie. You’re right in the center of the shot. Yeah, you’re fine, Charlie. It’s perfect. Right in the shot. Right in there…” That was Buster. He just volunteered that. He had nothing to do with the making of the shot at all, but he was directing that scene. He wanted to make sure that camera never got off Charlie. And he’s making certain that Charlie gets his shot.”

Keaton finished his part in Limelight on January 12, 1952. Chaplin wrapped the film thirteen days later, and began the lengthy process of winnowing more than 200,000 feet of exposed footage down to the 12,600 feet that would comprise the final cut. Keaton, recalled Claire Bloom, was “brilliantly alive with invention. Some of his gags may even have been a little too incandescent for Chaplin because, laugh as he did at the rushes in the screening room, Chaplin didn’t see fit to allow them all into the final version of the film.”

As Jerry Epstein clarified, “I was with him every second in the cutting room. He shot enough for ten films of material in that sequence. I used to say, ‘How can you cut your gags when they were so funny?’ He said, ‘We’ve got to keep it going. You can’t put in everything.’ And it was always the narrative that meant more than anything else—no matter how funny the gag is….Sure, he cut stuff of Keaton’s out, but he cut just as brilliant stuff of his own out because he knew it had to be sharp and fast.”

Ben Pearson, Keaton’s agent for the last fifteen years of his life.

When the deal for Limelight was made, it was through an agent named Ben Pearson, who had been involved in packaging the syndicated Buster Keaton Show for a firm called Stempel-Olenick. Formerly a writer for radio, Pearson took over for Leo Morrison after Morrison lost Spencer Tracy as a client and decided to close up shop. “He was ready to retire,” Eleanor said, “and he knew absolutely nothing—or wanted to know—about television coming in.”

The Federal Television Corporation was formed as a talent agency and packager with Buster Collier serving as president for a time and Pearson as vice president. It was Pearson who told Keaton he thought Chaplin’s offer—$1,000 for either one or two weeks—was on the cheap side for a billed appearance, but Buster said he would have done it for nothing. With the completion of Limelight, Keaton did something that would have horrified Chaplin. He made a flurry of live television appearances, managing six guest shots in the space of two weeks. The highest profile of these was Ken Murray’s “Salute to Movietime, U.S.A.” over on CBS, on which he reprised the molasses sketch, this time with comic Billy Gilbert in the role of the proprietor, and once again incorporating the “Butcher Boy” fall.

There would be more TV in the coming months, but nothing to rival the impact of an appreciation by Herald Tribune drama critic Walter Kerr that appeared in the May issue of Harper’s Bazaar. Its title was “Last Call for a Clown.”

“This is a love letter,” Kerr began, “some years late. But if I don’t get it off now, it may come altogether too late to do anyone much good. The curator of the Museum of Modern Art film library will tell you that the print of Buster Keaton’s The Navigator is wearing out. Unless an additional print can be uncovered in some unlikely vault, or unless a great deal of money is forthcoming to make possible a transfer onto fresh stock, no one is ever again going to see one of the two or three best films Keaton made. No one is ever again going to see one of the funniest—albeit one of the shortest—sustained shots in the history of the films. Keaton is the object of this love letter.”

While taking nothing from Chaplin, Kerr went on to deconstruct Langdon and, particularly, Lloyd, whom he saw as a symbol of his time rather than of the present. “We look at the man without very much recognition. The American image of itself has altered too profoundly in the intervening years for us to make spontaneous connection with this figure who was once so appealing, and Lloyd is somewhat trapped—as art, in its universals, is never trapped—in a passing phase. Keaton emerges the artist.”

The Keaton “mask” in Kerr’s estimation had a meaning. “It stood for stubbornness in the face of a tricky, hostile, and oversized universe….Behind the mask is an alert mind. It is a suspicious mind which expects the worst and is constantly on the qui vive against the next unpredictable, but inevitable, blow. But it is not a panicky mind; it is in full control of itself, unwavering, steady. When the blow falls, neither the mind nor the body recoils in terror.”

Kerr admitted his own rediscovery of Keaton came late, and that he was dubious about it. He recalled seeing The General as a teen and thinking it was good but not sensational. “A few years ago, through the services of the Museum of Modern Art, I saw The General again. I couldn’t believe my eyes. It not only hadn’t dated; it was funnier than it had been the first time.” Distrusting his own objectivity, Kerr tried the film out on a group of graduate students he was teaching, mixing in examples of Langdon and Lloyd as well. After a reel or so, they had abandoned their notebooks and forgotten completely they were watching a twenty-year-old comedy. “The General was, quite literally, the funniest film these people weaned on talking films had ever seen.”

Which brought him full circle to the point he made at the beginning. “The Museum of Modern Art, in its film footnotes, speaks of the ‘brilliance’ of Keaton’s style—an estimate it is impossible not to go along with once you have renewed acquaintance with the work—but in most quarters Chaplin is revered, Keaton forgotten. Keaton’s point of view is as defined as Chaplin’s, and every movement he makes, every frame of film in which he appears, belongs to it. If Chaplin was the little man doomed to be crushed, Keaton was the little man who couldn’t be crushed….His imagination is everywhere stamped on the work: in the story, in the direction, even in the subtitles. The unity that followed from this practice of pursuing a single vision—the comedian’s—raised the best silent comedies to a level of art no longer possible in the collaborative manufacture of the large studios. Hollywood became an assembly line, went in for piecework. Chaplin maintained his integrity, at a certain cost in technical proficiency, by holding onto his own studio and his own releasing organization. Keaton got lost in the vast shuffle of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

“A lot of Keaton is already gone for good. A laboratory fire wiped out his two-reelers and some of the early features, Three Ages among them. The Navigator may not be long for this world. Better hurry around next time the Museum is showing The Navigator, The General, or Our Hospitality. A great man is slipping away from you.”