WAKING YOURSELF  Brad Warner

Brad Warner

AFTER THE FIRST EDITION of Zig Zag Zen came out, I wrote some unkind things about it in my book Hardcore Zen (Wisdom Publications, 2003). But I have a confession to make. While I am not a fan of taking drugs to supposedly attain states of heightened spirituality, I have to admit that I am a great fan of all things psychedelic. I had my own psychedelic band in the 1980s called “Dimentia 13” who released five albums of trippy stuff. So I didn’t hate Zig Zag Zen quite as much as it seemed in my book. I thought the graphics looked damn cool and I agree that it’s important to discuss the relationship between drugs and spiritual practice since so many people are so deeply confused about the matter. I’m honored to be asked to contribute to this new edition.

The problem for me was that so many of the contributors to Zig Zag Zen who ought to have known better didn’t seem to be able to see the fundamental flaw in the logic of thinking that drugs could enhance spiritual practice.

LSD, mescaline, MDMA and all of the rest of the drugs promoted as tools for spiritual enhancement do nothing in and of themselves to give a person access to states of higher consciousness. Rather, they induce a highly confused mental state that traumatizes the mind and body. Any kind of trauma can have the side effect of inducing what are often called “spiritual experiences.” People have had great awakenings after being involved in car crashes or wars. But nobody believes car crashes and war are intrinsically spiritual.

I don’t doubt that drugs often act as a kind of catalyst to further exploration of meditation and other related practices. Car crashes, wars and other such traumatic experiences often have the same effect. Nobody would keep crashing their car again and again hoping to have another spiritual awakening. Yet some people believe they can deepen their spiritual experiences by taking more and more drugs.

Western society is obsessed with medication. Because medical science has advanced so far so quickly, we are prone to imagine that drugs could cure any illness if only we could find just the right combination of chemicals. So naturally, when we hear representatives of Eastern religions describe our normal condition as diseased, we wonder what we can take to fix that. The notion that there might be a pill to make us Enlightened seems like it makes perfect sense.

The idea that psychedelic drugs might be able to do in minutes what used to take years of deep introspection and hard practice has recently made a major comeback. As if the Sixties and Seventies taught us nothing, there is a whole new generation promoting hallucination as a substitute for meditation. The first edition of Zig Zag Zen provided these folks with numerous supposed experts to support this view, and I’m sure this new edition will do the same.

I don’t doubt that these formerly vilified medications can have therapeutic uses and I’m glad that research is being done in that area. But the question of whether or not they can be used as a shortcut to the goals of Buddhist practice is one that I think the Buddha might have answered with his characteristic phrase: “The question does not fit the case.”

James Hughes, PhD, Executive Director of the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies, a bioethicist and sociologist at Trinity College, recently published his views in an article titled “Using Neurotechnologies to Develop Virtues: A Buddhist Approach to Cognitive Enhancement” on the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies website (ieet.org), available as a pdf at: http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1093&context=facpub.

In the article Dr. Hughes postulates ways in which various psychoactive drugs might help those who are not genetically predisposed to do so follow various Buddhist paramitas (perfections) of generosity, proper conduct, renunciation, transcendental wisdom, diligence, patience, truthfulness, determination, loving-kindness and serenity. For example, he speculates that MDMA (which those who came of age during the 1990s rave scene will know as “Ecstasy”) could be used to chemically stimulate the Buddhist virtue of loving-kindness. Drugs being developed to treat Alzheimer’s and Down syndrome might, he hypothesizes, be used to bring about the transcendental wisdom spoken of in the sutras.

He goes even further, envisioning a future wherein, “we will have the capacity to change genes that affect the brain permanently, and install neurodevices that constantly monitor and direct our thoughts and behavior” in order that we all might follow the Buddhist perfections.

But I have to wonder who is going to program these neurodevices or decide which of my genes need changing. Based on what criteria? Who decides what is and is not enlightened thought and behavior? Do we really want devices of any kind directing our thoughts and behavior even if it means we’ll behave in ways that someone has designated as “Enlightened?” Do we really want someone’s ideal of a perfect society enforced upon us by genetic manipulation and machines in our brains even if that perfect society is labeled as “Buddhist?” And even if we do, what happens when the devices break down?

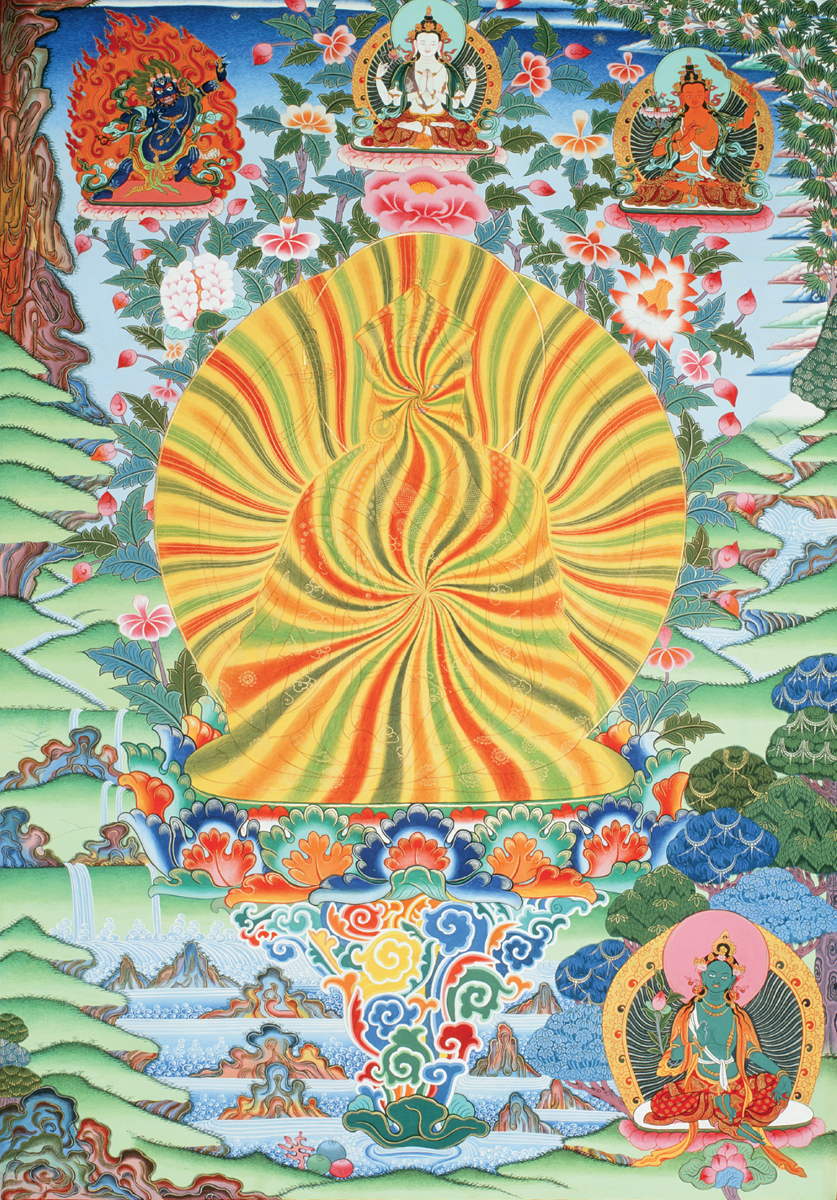

RAINBOW BODY PADMASAMBHAVA/Guru Rinpoche Gana Lama, 1992

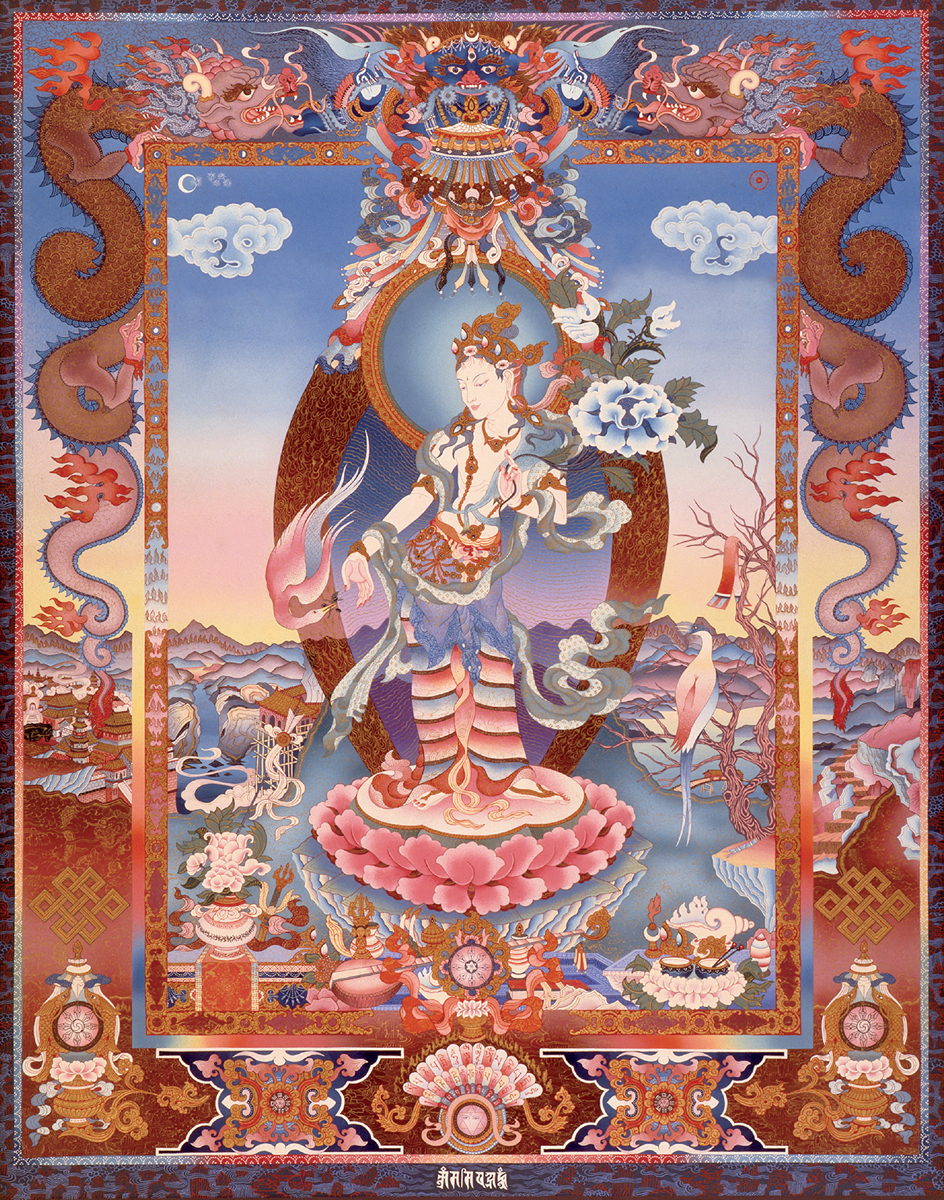

PADMAPANI AVALOKITESHVARA Robert Beer, 1976

FOUR-ARMED AVALOKITESHVARA Robert Beer, 1975

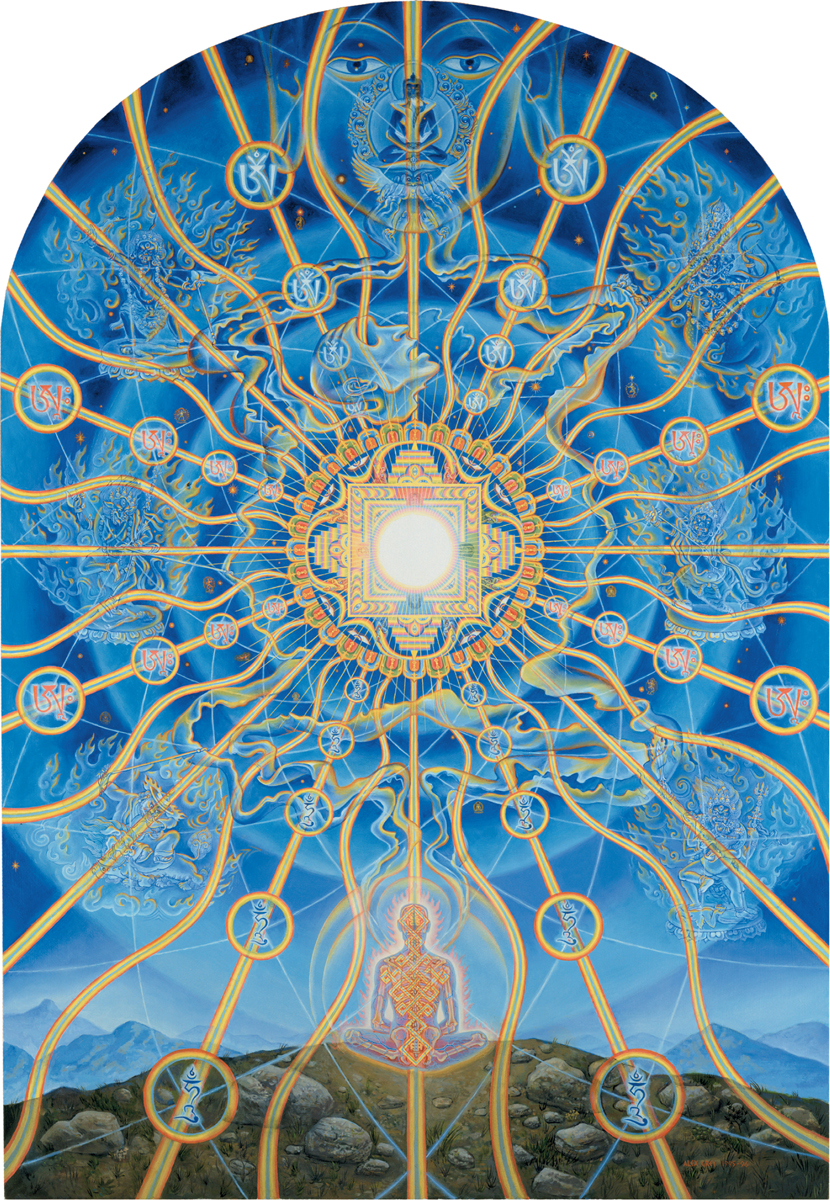

NATURE OF MIND (Pane l4) Alex Grey, 1996

TETRAGRAMMATON Carey Thompson, 2011

REGENERATION Amanda Sage, 2012

THE ENLIGHTENMENT Robert Venosa, 1977

GREEN TARA Anonymous, 17th century

Once during a sesshin, a participant waxed lyrically about the benefits of the kiyosaku, the “staff of instruction” used in many Zen temples to stimulate effort in sleepy meditators with a sharp whack across the shoulders. My teacher, Gudo Nishijima, who never used the kiyosaku listened patiently and finally said, “Maybe that’s true. But I think it’s better to learn to wake up by yourself.”

The basic problem with Dr. Hughes’ speculations and the opinions of the many supposed experts who think drugs can enhance or initiate spiritual experiences is that a crucial element of Buddhist practice is learning to wake up by oneself. Even if drugs and genetic manipulation could be used to create real compassion, loving-kindness and so forth—and I don’t believe they can—this would not be at all the same as learning how to have these qualities by oneself. What happens when your prescription runs out or your insurance gets canceled? How much does loving-kindness cost at your local pharmacy?

Dr. Hughes, and the many others who find his line of thinking reasonable, imagine that Buddhist practice is all about goals. They imagine that we strive to have transcendental wisdom and use meditation as a means to reach this goal. Since they seem to believe that reaching our goal is the point of the exercise, wouldn’t it make more sense to get there as quickly as possible by taking a pill?

But Buddhist practice is never about creating goals and trying to achieve them. It’s about learning to see our own real state in each and every moment clearly for ourselves. As we come to see what life really is, we begin to behave more logically and ethically because that’s what makes sense. Drugs can’t help us with that. Buddhist practice is a journey to be enjoyed and savored, not a race to be won quickly and efficiently.

Supporters of drug use as a way to gain spiritual insight often fall back on the cliché that drugs are like taking a helicopter to the top of a mountain rather than climbing it, to which they liken long-term meditation practice. A guy in a helicopter gets the same breathtaking view as someone who has climbed the mountain, but he gets there much quicker and more easily. “You can’t deny it’s exactly the same view,” a supporter of this idea told me once. But, in fact, I would unequivocally deny that it’s the same view. It’s not.

Let’s say you meet a veteran mountaineer with over a quarter century of climbing experience, a person who has written books on mountain climbing and given personal instruction to others in the art of climbing. And let’s imagine what would happen if you tried to convince this guy that people who take helicopters to the tops of mountains get everything that mountain climbers get and get it a whole lot easier. The mountain climber would certainly tell you that the breathtaking view a guy who takes a helicopter to the top of a mountain gets is not in any way, shape or form the same view experienced by a person who climbs the mountain unassisted.

To the mountain climber, the guy in the helicopter is just a hyperactive thrill seeker who wants nothing more than to experience a pretty view without putting any effort into it. The helicopter guy thinks the goal of mountain climbing is to be on top of the mountain and that climbing is an inefficient way to accomplish this goal. He just doesn’t get it.

The helicopter guy misses out on the amazing sights to be seen on the way up. He doesn’t know the thrill of mastering the mountain through his own efforts or the hardships and dangers involved in making the climb. And he’ll never know the awesome wonder of descending the mountain back into familiar territory. All he’s done is paid some money to a person who owns a helicopter. He probably couldn’t even find the mountain himself, let alone make it to the top. When there are no helicopters around, the poor guy is helplessly grounded.

To a mountain climber, the goal is not the moment of sitting on top enjoying the view. That’s just one small part of the experience. It may not even be the best part. To a mountain climber, every view, from every point on the mountain is significant and wonderful.

People who think that the pinnacle of the experience is that moment of being right on the tippy-top, don’t understand the experience at all. The poor attention-addled persons probably never will.

What I am working on in meditation involves every single moment of life. So-called “peak experiences” can be fun. But they no more define what life is about than so-called “mundane experiences.” When you start making such separations, you have already lost the most precious thing in life, the ability to fully immerse yourself in every experience.

Whenever someone puts forth ideas like this, they generally bring up the Buddhist prohibition against the use of intoxicants and then use clever wordplay to pretend it doesn’t really matter. The usual tactic is to claim that this prohibition is only against certain “bad” drugs, not the “good” drugs they recommend. “While alcohol, opiates and cannabis certainly could not create a permanent state chemical happiness, much less facilitate spiritual insight,” Dr. Hughes says, “the neurotechnologies of this century might create permanent changes of mood.”

But the Buddhist prohibition against intoxicants isn’t about bad drugs versus good ones. It’s about learning to wake up by oneself. A thousand years after the Buddha, Dogen Zenji amplified the precept saying his students should not try to augment their practice by taking “medications prescribed for mental diseases.” The notion that Buddhist virtues could be stimulated chemically has been with us a long time. And so has the knowledge that this goes against the very core of what Buddhism is about.

I also enjoy the way some people want to have it both ways. They laud the use of peyote and psilocybin mushrooms in ancient and indigenous religious rituals while ignoring, and in doing so, denigrating religions and cultures that regard cannabis, opiates, alcohol, and even tobacco as sacraments capable of creating deep spiritual insights.

The Buddhist way is to do without drugs or enhancements of any kind. This is an intrinsic aspect of the path. The use of drugs, gene manipulation or brain implants to enhance our mental states runs counter to the very core of what Buddhist practice is all about: Learning to wake up by yourself.