FOUR

“My Dander Was Up”

FOR MOST OF THE FIRST HALF OF HIS LIFE David Crockett had lived from day to day, driven by the barest necessities of food, clothing, and shelter. His connection to the outside world, to the affairs of the nation or state, or even political circumstances affecting his own region, mattered little to him until his family had settled tenuously on Bean’s Creek and a grave situation of immediate concern arrived smack on his doorstep.

1

Crockett well knew that his own country was technically at war, since even the semiliterate would have seen the regional papers on June 4, 1812, announcing that the House of Representatives had voted a declaration of war against Great Britain. The British had persisted in seizing American sailing vessels, refusing to vacate forts and outposts on American territory.

2 Within a week, President James Madison had signed the bill and the nation was officially at war. But this meant effectively little to the lives of struggling frontier families who viewed the war as the government’s problem. However, the British soon managed to bring the matter closer to home when they began to coerce Indian allies from as far north as the Canadian boundaries to the southern reaches of the Gulf Coast,

3 convincing them (with money, goods, and weaponry) to resist the settler’s encroachment by any means possible. Crockett remembered the stories of the attacks by rampaging Indians on his own parents and grandparents, and he was aware of the dangers they presented, but his was generally a noncombative nature, unless he was provoked. Though his temper was short, Crockett was more of a prankster who liked a good time. While he wasn’t opposed to a little playful scuffling among the boys, actual war was another matter entirely. “I, for one, had often thought about war, and had often heard it described; and I did verily believe in my own mind, that I couldn’t fight in that way at all.”

Just as the young Crockett family was settling in on Bean’s Creek, relations between settlers and the native population stretched perilously, then finally snapped. The whites continued their ceaseless pouring in and scattering out to the west and south, pushing populations of the Creek Nation to frustration and anguish as whites squatted on and acquired disputed lands. By circumstance, Crockett and his family were part of this exodus, and they dwelt on the cusp of what would come to be known as the War of 1812, and its bloody offshoot, the Creek War.

Due south, around the gulf port of Pensacola, tensions were high and the political situation was complicated. In addition to the growing English and Indian alliance, the Spanish, having yet to agree that West Florida had been annexed by the Louisiana Purchase, created a thorny problem by supplying Gulf Coast Indians with arms and hard goods, even food.

4 In July 1813, an armed band of Indians were moving north to their Upper Creek villages along the Pensacola Road when they were surprise-attacked by a party of 180 soldiers. The Creek band, numbering between sixty and ninety,

5 were resting in the south Alabama shade after a noon meal when the first volleys sprayed down upon them. The Indians scattered into the woods, dispersing but remaining quiet and on guard. Relishing the easy victory, the soldiers moved quickly in and began to loot the stores, supplies, and gunpowder abandoned by the Creeks. The greed proved a tactical mistake. Outnumbered by more than two to one but emboldened with anger, the band of Red Sticks (so named for their practice of painting their war clubs bright red to symbolize the blood of their fallen enemies), led by mystics Peter McQueen and High Head Jim, erupted screaming from the woods and violently drove away the numerically superior force.

6They had also managed to shame and enrage the whites, who took shelter and nursed their wounds at Fort Mims, a temporary installment erected around the home of Georgia trader Samuel Mims. The structure, about forty miles north of Mobile near the Alabama River, served as a safe haven and way station for troops moving through the region. As it turned out, their security at this outpost was more perceived than real.

The Creeks were ripe for retaliation. For some time they had been rallying behind the emotional and spiritual guidance of the great Shawnee chief, Tecumseh, whose name, legend, and uncompromising beliefs still echoed across the Appalachians. Tecumseh’s resonating oratory had inflamed and inspired the Creek Nation. He had witnessed and endured enough displacement, enough broken treaties, enough illegal ransacking of Indian land. He raged and railed, inciting his people to action:

Let the white race perish. Back whence they came, upon a trail of blood, they must be driven. Back! Back into the water whose accursed waves brought them to our shores! Burn their dwelling—destroy their stock—slay their wives and children, that the very breed may perish. War now! War always! War on the living! War on the dead!

7

Tecumseh’s agenda had been bold, unwavering, and visionary—he would lead a confederacy of Indian tribes, stretching from the St. Lawrence River near the Canadian border and sweeping through the mountains and seaboard all the way south to the Gulf of Mexico, in a sustained attack against the violating white settlements. Only such a determined and organized cooperation among native people would realize his dream, “to sweep the white devils back into the ocean whence they had come and restore the continent to its rightful owners.”

8Such was the sustained wrath that the Red Sticks brought to Fort Mims on August 30, 1813. With the memory of the brutal surprise attack at Burnt Corn still fresh and the wrath inspired by Tecumseh coursing through the Red Sticks’ warring veins, Chief Red Eagle (William Weatherford) led a stealthy attack on the encampment. The Red Sticks were soon amazed to find the gates normally barring entry to Fort Mims wide open—and unguarded! At high noon the Indians streamed into the defenseless fort, striking down a Major Beasley, who at last and too late had arrived to defend the gates. War whoops wailed across the grounds and soon Creeks overwhelmed the garrison in what would later be described as among the more shocking and barbarous massacres in the annals of frontier history. Dreadful carnage continued for the next few horrific hours. “The bullets, the knives, the war clubs, the tomahawks, the flames did their work, and more than half a thousand human beings in a few hours perished.”

9Though the attack was in fact retaliation, the grotesque nature of the slayings would be most remembered among settlers. Women and children were corralled, then butchered and scalped. Young children were held by their legs and flung, their heads battered against the stockade walls. Women were tackled and bludgeoned, and the pregnant women were eviscerated, their unborn infants ripped from their wombs. Blood lust consumed the marauding Creeks, and though Chief Red Eagle later claimed he wanted no part of the massacre and had only intended to fire warning shots, once it started he was helpless to stop the revenge. In the end, 275 settlers, friendly Indians and mixed-bloods lay dead; only a small and terrified number escaped the smoldering fort to tell their harrowing tale.

10News of the massacre traveled like wildfire across the frontier settlements, arriving even to quiet and pastoral Bean’s Creek, where Crockett would have been out hunting along the banks, watching snapping turtles sunning on rocks, listening to the rising of trout in the slow-moving water. When he got word of the attacks, Crockett’s normally congenial nature shifted and he determined that it was time to fight, perhaps as he remembered what had happened to his own family:

For when I heard of the mischief which was done at the fort, I instantly felt like going, and I had none of the dread of dying that I expected to feel . . . I knew that the next thing would be, that the Indians would be scalping the women and children all about there, if we didn’t put a stop to it.

11

But packing up and running off to fight would come at a significant familial cost, and Polly begged Crockett not to go, arguing that she was in a strange land, and remaining alone raising two young boys was a frightening prospect for her, as fit and able as she was. In his absence, who would work what little ground they were attempting to farm? Who would provide them with meat? Her arguments impressed him, and he thought carefully about the consequences, and about her desires. Finally, the general call to arms, prompted by Tennessee Governor Willie Blount, and an innate patriotism, made up Crockett’s mind. “I reasoned the case with her as well as I could, and told her, that if every man would wait till his wife got willing for him to go to war, there would be no fighting done, until we would all be killed in our own houses . . . and I believed it was a duty I owed to my country.”

12Though Polly fought his decision with pleading and tears, she ultimately turned back to her weaving and the duties of the farm as he rode off to fight the Indians. “I was bent on it,” Crockett later admitted. “The truth is, my dander was up, and nothing but war would bring it right again.”

What Crockett would come to understand soon enough was that political machinations of national import were already at work, and that the muster to which he was responding was part of a broader movement generated from Washington itself. The Madison administration understood that these skirmishes and uprisings, incited by Tecumseh, needed to be thwarted before they gained momentum and spread to many tribes. The plan was to muster and send four armies—from Georgia, the Mississippi Territory, and Tennessee—into the heart of the Creek Nation, and convene their forces at the confluence of the Tallapoosa and Coosa rivers. The commander of the army from West Tennessee was General Andrew Jackson, a fierce, ambitious, and disputatious man with a penchant for dueling. Jackson had earned a reputation as a man not to be trifled with, an intimidating and unreasonable grudge-holder. He had killed Charles Dickenson in a duel in 1806, and was later embroiled in a scandal that threatened to tarnish his growing political reputation when he became involved in another duel between one of his young officers, William Carroll, and Jesse Benton. At the City Hotel in Nashville, tempers flared and four guns were fired, and though there remains disagreement about who fired first, Jackson took a bullet in the shoulder and was badly injured.

13 The incident cemented his image as a man with a hair-trigger temper. Jackson’s shrewd political mind also understood that military fame and glory were absolute necessities for professional political advancement, and he had long champed at the bit to go fight Indians. By his early teens he had already developed deep and unwavering prejudices against the native people. Like many migratory whites, Jackson “accepted as indisputable fact that Indians had to be shunted to one side or removed to make the land safe for white people to settle and cultivate. The removal, if not the elimination of the Indian from civilized society, became ingrained in the culture.”

14What Crockett did not know was that the army he was about to join and the battles he was soon to fight would help deliver Andrew Jackson, the man who would eventually become his nemesis, straight to the steps of the White House.

Polly had packed him down with as much dried and salted meat as he could possibly carry. He then mounted and waved good-bye to her and the boys as he rode off to Beaty’s Spring, south of Huntsville, Alabama, where troops were gathering. “At last we mustered about thirteen hundred strong, all mounted volunteers, and all determined to fight, judging for myself, for I felt wolfish all over. I verily believe the whole army was of the real grit.”

15 Most men, like Crockett, had left their women and children at home alone, or with relatives and neighbors, to fight a nebulous enemy, and the fear and uncertainty moved through the camp. Commanders reminded the men of the dangers they were to encounter, offering any who wished to leave the chance, before they were officially signed on for service. Crockett noted with pride that none took up the offer. Crockett himself signed on for a ninety-day enlistment.

16Word went round the spring that General Andrew Jackson was on his way south from Nashville with a horde of foot soldiers and mounted men, and fear grew into excitement. While they waited, Major John Gibson arrived, seeking volunteers to go with him into Creek country on a scouting mission. He wanted two of the most experienced woodsmen and marksmen available. David Crockett was immediately selected, proudly asserting that he would “go as far as the major would himself, or any other man,” providing that he could select his own partner. Crockett selected a young man named George Russell, a son of old Major Russell, also of Tennessee. When Major Gibson saw Crockett’s choice, he balked, claiming the stripling hadn’t beard enough—he sought men, not mere boys. Crockett later confessed he was “nettled” at the major’s doubt in his choice, for he valued Russell’s pluck, and did not believe that age determined bravery: “I didn’t think that courage ought to be measured by the beard, for fear a goat would have the preference over a man.”

17 After some argument on the matter, Crockett held firm to his convictions, explaining that he had more knowledge of Russell’s abilities, and eventually Gibson acquiesced.

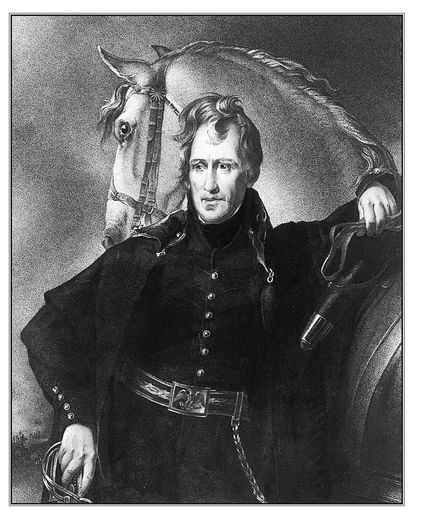

“Old Hickory.” Andrew Jackson as he might have appeared when Crockett first met him during the Creek War. (Andrew Jackson. Hand-colored stipple engraving by James Barton Longacre, copy after Thomas Sully, 1820. Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC.)

David Crockett had entered the fray.

18 Major Gibson, Crockett, George Russell, and ten others headed out, crossing the Tennessee River at Ditto’s Landing, then moving slowly and quietly due south about seven miles, making camp at nightfall. The next morning, Gibson and Crockett agreed that they would cover more ground, and more stealthily, if they split up, so Gibson took seven men and Crockett was placed in charge of five, and they agreed on a rendezvous point that evening some fifteen miles away. The loose plan was for Gibson to pass by the home of a “friendly” Cherokee named Dick Brown (who would later become a colonel and serve under Jackson), and Crockett to go by Brown’s father’s place, each to obtain all the intelligence they could to share when they met up. Crockett made it to the elder Brown’s place, then enlisted a half-blood Cherokee named Jack Thompson to serve as a sentry. They agreed to communicate using owl hoots to avoid detection by hostiles. Crockett got to the rendezvous point that evening, and waited until nearly dark, but still Major Gibson failed to arrive. Knowing the road to be unsafe, Crockett took his men away from the well-used “Indian trace” and found a secluded hollow where they struck camp.

Deep in the night Crockett heard the screechy hoot of an owl, and he called back, and Jack Thompson emerged from the woods to report no sign of Gibson in the vicinity. They rested there until morning, but still Major Gibson failed to arrive. Here Crockett made his first significant military decision. Some of the men wished to return, spooked by the prospect that Gibson and his men had been butchered, but Crockett reminded them of their duty, that they had “set out to hunt a fight,” and that they were bound to “go ahead, and see where the red men were at.”

Moving quietly and carefully, they proceeded to a Cherokee town some twenty miles distant. At midafternoon of the second day they came to the home of a man named Radcliffe, who had married a Creek woman, had two sons, and was living in relative harmony on the edge of the Creek Nation. Radcliffe was well stocked, and he fed Crockett’s company and their horses, providing the hungry men with “a great deal of potatoes and corn, and indeed, almost everything else to go on.” But Radcliffe himself was “bad scared all the time,” noting that just an hour earlier there had been “ten painted warriors at his house,” and if Crockett and his boys were discovered there, the whole lot of them would be killed for harboring the soldiers. Again Crockett’s men voiced their concerns and suggested they leave, but Crockett scoffed that his business had been to hunt “just such fellows,” so they saddled up and readied to ride on. Crockett also understood that under such circumstances, it would be cowardly to return to camp.

They rode into the night, their shadows passing through the trees under brilliant moonglow, all of them afraid to talk for fear of the “painted warriors.” They moved this way, sometimes riding and sometimes leading their horses through slanting moonlight and dark shadow, across creeks and ponds, until they came upon “two negroes, well mounted on Indian ponies and each with a good rifle.” Ironically, the men were slaves who had been stolen from their owners by the Indians, and had fled them, and were now attempting to get back to their white masters. The two were brothers, big friendly fellows, and each could speak in Creek dialect as well as in English. Crockett convinced one to continue on to Ditto’s Landing, the other he adopted as a guide and translator. Eventually they heard voices and discerned the flickering of firelight through the trees, and arrived at the encampment of a group of friendly Creeks.

Some of the boys had bows and were firing arrows into the trees by the fire and moonlight, and Crockett, playful and inquisitive even under the dangerous conditions, proceeded to join in, amusing himself and “shooting with their boys by pine light.” Finally the newly enlisted slave guide returned from speaking with some of the Indian elders, his face grim. He told Crockett that the friendly Indians were concerned, and if the Red Sticks found them there they would all be killed. Crockett relayed the following message back through his translator: “If one would come that night, I would carry the skin of his head home to make me a mockasin.” The friendly natives laughed aloud at the correspondence, admiring Crockett’s nerve and humor, but unease spread across the camp, and the men left their horses saddled for a speedy departure, and they lay down, attempting to get what little rest they might with their rifles clutched across their chests.

Crockett lay dozing fitfully when he was startled awake by “the sharpest scream that ever escaped the throat of a human creature.” An Indian runner arrived in camp and reported that the Red Sticks were coming, and that a large war party had been “crossing the Coosa River all day at Ten Islands, and were going to meet Jackson.” Crockett believed he finally had some useful intelligence, and he felt compelled to convey the news quickly. News of Red Sticks on the warpath sent the friendly Indians into a frenzy, and they packed up and scattered in a matter of minutes. Crockett gathered his men and they quickly mounted up, knowing they had a long and dangerous ride ahead. By now, they were some sixty-five miles from the landing. They stopped only to water and feed their horses, riding through soreness and hunger and fear, until they came once more to the friendly Indian community where they had met Radcliffe, now vacated and ablaze. Crockett later boasted that they could easily have taken on a force of five to one, then mused wryly: “But we expected the whole nation would be on us, and against such fearful odds we were not so rampant for a fight.”

The torched town at their backs, they rode by moonlight through the night, and stopped at daybreak at the Brown residence, to feed their horses and eat a hurried meal themselves. At about ten o’clock the next morning they straggled into the main camp, their horses limping and foaming, the men hunched, saddle-sore. Crockett dismounted and reported immediately to Colonel John Coffee the news from the front. Coffee took in the information but seemed to pay little attention to it, practically ignoring Crockett, who fumed quietly, not wishing to offend a superior: “I was so mad that I was burning inside like a tarkiln, and I wonder that the smoke hadn’t been pouring out of me at all points.” His rightful anger at being disregarded would shortly turn to real bitterness. Major Gibson, who had been presumed dead, emerged the next day, and when with great histrionics and embellishments he relayed nearly the identical information that Crockett had previously brought to Colonel Coffee’s attention, the Colonel acted immediately. Many years later Crockett would still remember that feeling of disparity, of being ignored simply because he was a common foot soldier and not an officer. It convinced him that the world could be hierarchical and unfair. “When I made my report, it wasn’t believed, because I was no officer; I was no great man, just a poor soldier. But when the same thing was reported by Major Gibson!! Why, then, it was all as true as preaching, and the colonel believed it every word.”

This perceived betrayal would be the seed of a growing distrust in Crockett, a deep suspicion of rank and privilege that would eventually fester into near-hatred.

19 At the time, Crockett simply took the insult quietly and went about his business, as immediate action was called for. Under orders, the troops erected breastworks nearly a quarter-mile long around the camp, and Colonel Coffee dispatched news of the developments via Indian runner to General Jackson, now stationed at Fayetteville.

Jackson was in no mood for the information. He had only arrived the previous day, and his arm was bound and useless, injured by gunshots in the aftermath of the duel between Carroll and Benton. The wounds had been very serious, a bullet having pierced, and remaining lodged in, his upper left arm, another slug having shattered his shoulder. Using “poultices of elm and other wood cuttings as prescribed by Indians,”

20 a doctor staunched the blood flow that might have killed him; it took Jackson almost a month before he was fit to rise from bed. But Jackson, as his men were coming to understand, was no ordinary man, and it would take more than a shattered arm to sideline him. As it turned out, he would carry that bullet with him through the Creek War, the Battle of New Orleans, and right into the White House, where it would finally be removed in 1832, in an operation without anesthesia, by a prominent Philadelphia surgeon.

21So it was that Jackson mounted up and drove a furious forced march from Fayetteville, arriving at Crockett’s camp in some discomfort, his men’s feet raw and blistered from the speed of their journey. Already, for the last six months or so, Jackson’s men had privately been calling him by a nickname. Noting his toughness, willpower, and refusal to yield to anything, they dubbed him “Old Hickory,” and the name stuck.

22 On October 10, 1813, acting on news conveyed to him by Colonel John Coffee but first iterated by David Crockett, an able volunteer of the Tennessee Mounted Militia, Old Hickory, his left arm slung tight to his body and his face stern and narrow but betraying no sign of pain, rode into camp and dismounted. The fight with the Indians he had longed for was about to begin in earnest.

The breastworks that the troops had erected were never put to use in defense, for Jackson’s ire was up, and he quickly determined that the best tactic was to go on the offensive, to intercept the mobilizing Creeks to the south. Fatigued and hungry but now driven by the possessed Old Hickory—“Sharp Knife” to the Indians who faced his blade—the Tennessee Volunteers marched and rode for Creek country, essentially retracing Crockett’s reconnaissance by crossing the Tennessee River, moving through Huntsville, then fording the river again where it passed Muscle Shoals. Jackson had split his forces, sending about 800, Crockett among them, under Colonel Coffee. The river at Muscle Shoals was dangerous, nearly two miles wide, with a bottom so rough and rocky that a number of horses’ hooves became lodged between submerged stones. The riders leapt from them into the water and sloshed along on foot, leaving the panicked animals to founder, topple, and eventually drown in the muddy roil. The men drove on to the headwaters of the Black Warrior River, very near the present-day location of Tuscaloosa, and moved as quietly as a troop of 800 could into what was known as Black Warrior Town. It had recently been vacated, and the hungry soldiers proceeded to loot what stores remained, securing “a fine quantity” of beans and corn. Content with new food supplies, they then torched the town down to ash.

Crockett noted that the fields surrounding the town were pocked with very fresh Indian tracks, and he surmised that the Indians had anticipated their arrival and fled not long before. They pressed on, a number of the men now gaunt and haggard, heading to meet Jackson’s main army at the fork where Crockett was originally to have made rendezvous with Major Gibson. The forces convened and reassessed the situation, realizing by the next day that they were completely out of meat. Jackson’s army had originally assembled and moved so fast that they had arrived insufficiently supplied, and Crockett’s division had used up all the provisions they had brought. Crockett took the opportunity to approach Major Gibson and ask him whether he might venture afield to hunt as they marched along, and Gibson consented, perhaps wishing to confirm the rumors of Crockett’s hunting skills and marksmanship. They certainly needed the food.

Crockett left the main and had gone only a short distance when he came across a fresh-killed deer carcass, so recently dropped that the flesh was “still warm and smoking.” Crockett surmised that the Indian who had killed the deer would be very close at hand, perhaps still in shooting range, and though, as he put it, “I was never much in favor of one hunter stealing from another, yet meat was so scarce in the camp, that I thought I must go in for it.” Without hesitation he slung the bloody carcass in front of him across his horse and rode with his spoils until nightfall.

Returning to camp, he distributed the deer among the men, keeping a small portion for his immediate group, and they gorged themselves on the venison and gnawed on small rations of parched corn. The next day Crockett hunted again, this time flushing a pack of hogs from a canebrake and shooting one, and in moments gunfire erupted all around, sounding like battle fire. When Crockett arrived back with his hog he happily discovered that the hogs had broken from the cane toward the camp, and the soldiers had harvested a good number of them, and a hefty beef cow as well. They were temporarily sated, but things would soon get worse again. “The next day we met the main army, having had, as we thought, hard times and a plenty of them, though we had yet seen hardly the beginning of trouble.”

Crockett’s foreshadowing would prove accurate, as the men would soon face hardships so severe as to test their tenacity and patriotism and result in a famous mutiny. The convened armies plodded on, arriving back at Radcliffe’s place, only to find that Radcliffe had stashed and hidden all his provisions. Even more remarkable was the revelation that the runner who’d screamed in the night and claimed that the “Red Sticks” were on the move had actually been an elaborate and successful ruse by Radcliffe himself. They had been tricked, and Crockett noted that there was nothing much to do about it but march on to Camp Wells, between Tuscaloosa and Gadsden. They vowed retribution against the scheming Radcliffe, and for atonement they absconded with “the scoundrell’s two big sons . . . and made them serve in the war.” At length they came to Ten Islands, on the Coosa River, where Coffee’s troops erected a stockade named Fort Strother and began to send out small spy parties to get detailed and confirmed intelligence on the Creek activity and locations. These forays paid off, as it was soon determined that a fairly large contingent of Indians remained encamped at the town of Tallusahatchee only eight miles away. This was it; Jackson’s chance to avenge the atrocity of Fort Mims was now at hand.

General John Coffee (he had just recently been given the raise in rank) divided his troops and cleverly marched one line on either side of the town, and in this way used a force of some 900 men to completely encircle a town, and within it, about 180 Creek warriors. They tightened their line. Clearly outnumbered, a good many Creek women began fleeing from houses and shelter and clinging to the soldiers, begging mercy, surrendering. But with Fort Mims still a vivid memory and rallying cry, Coffee’s men closed their ranks tight and Captain Eli Hammond, commanding a band of rangers, advanced straight on the town. Crockett remembered that “Indians saw him, and they raised a yell, and came running at him like so many red devils.” The outnumbered Indians fired guns and arrows when they could, then quickly retreated into houses and behind outbuildings, waiting. What followed was a scene as gruesome as Fort Mims. Crockett and his contingent chased a group of forty-six Creek warriors into a house, and arriving there, watched as a brave and unyielding Creek squaw drew a bow back with her feet and let fly an arrow that pierced and slew one of their men. It was the first man Crockett ever saw killed by bow and arrow, and the act enraged him and his men. “She was fired on, and had at least twenty balls blown through her. . . . We now shot them like dogs; and then set the house on fire, and burned it up with the forty-six warriors in it.” Similar routs took place all around the town, and in a very few minutes the attack was complete, with 186 Creek warriors dead and eighty taken prisoner. Just five of the white troops perished in the raid. Jackson would comment, “We have retaliated for the destruction of Fort Mims.”

23The next day, November 4, 1813, Crockett and some of his men returned to the Indian town to see what provisions might be salvageable, for the men were by this time exceedingly hungry and without reinforcements or arriving supplies. Crockett witnessed a macabre scene of dead, bloated, and half-charred bodies strewn across the town. “They looked very awful, for the burning had not entirely consumed them, but given them a very terrible appearance, at least what remained of them.” Buildings creaked and groaned, half-toppled and smoldering, and they found one large house that had a big store of potatoes underneath, in its cellar, and Crockett noted that “hunger compelled us to eat them, though I had a little rather not, if I could have helped it, for the oil of the Indians we had burned up on the day before had run down on them, and they looked like they had been stewed with fat meat.”

24The stores of found food proved insufficient, and Crockett returned with these men to Fort Strother, where everyone was near starvation. They rested and attempted to recuperate for a few days. Crockett noted that food was so scarce they were forced into “eating beef-hides, and continued to eat every scrap we could lay our hands on.” Men grew weak, sicker than they had already been, and morale fell dangerously low. Then, on November 7, news came from a runner that Fort Talladega, just thirty miles to the southeast, was under siege by a large band of hostile Creeks. The runner, the chief of a friendly band of Creeks ensconced in the fort, had escaped in a hogskin and himself run the thirty miles to take personal audience with General Jackson.

25 Jackson did not delay, ordering his men to march immediately and not stop through the long night.

At sunrise, Crockett and his cohorts arrived near the fort to find “eleven hundred painted warriors, the very choice of the Creek nation.” The hostile Creeks had surrounded the fort, which housed a good number of friendly Creeks, and the hostiles were attempting to coerce the friend-lies to join them in a fight against Jackson and his army, bribing them with the lure of guns, money, fine horses, blankets, and a host of other spoils of war, which were exaggerations given the army’s actual threadbare condition. The military tactic Jackson would employ was the same that had worked at the bloody massacre of Tallusahatchee: surround and encircle the enemy with two connecting lines of men, then tighten the circle and squeeze them into panic.

Crockett and his men, under the direction of Major Russell, moved in on the fort, but they saw no activity; they heard only the voices of friendly Indians hooting and calling out, attempting to warn the soldiers about an ambush. Enemy scouts had signaled the soldiers’ arrival, and thousands of war-ready Creeks lay hunkered down, concealed under the riverbanks of a branch that curved around the fort “in the manner of a half moon.” They waited patiently, some almost fully submerged in the icy water, others lurking stealthily quiet in the woods between the stream and the fort. Finally, nervous friendly Indians, noting that the soldiers were not heeding their warnings, ran out from their positions around the fort to the front of the line. The disturbance halted the march, and not wishing to miss the opportunity, the Creeks hidden beneath the stream opened fire. When some of the soldiers began to retreat, Indians poured from the banks in waves, a thousand or more, and Crockett noticed with some trepidation that “they were all painted scarlet, and were just as naked as they were born.” The Indians fired as they ran, and “came rushing forth like a cloud of Egyptian locusts, and screaming like all the young devils had been turned loose, and the old devil of all at their head.” Some of Russell’s men dismounted and ran on foot to the security of the fort, and horses, cavalry soldiers, and Indians swirled in a chaotic mass of gunfire and screams. Crockett’s company waited until the Indians ran shrieking within close range, then lowered and let fire, killing many and sending them fleeing toward the other line. The Indians were caught in a downpour of deadly crossfire, and the soldiers killed “upwards of four hundred of them.”

In the battle frenzy, the warriors retaliated with guns, bows and arrows, and tomahawks, and a large group managed to create enough sustained pressure to cause a rift in the army’s line. Crockett remembers that they were drafted militia whose line parted, and this gap let a considerable number of Indians escape and begin an effective counterattack, forcing a livid General Andrew Jackson to retreat. Jackson later fumed, “If the line had not given way, [we] would have repeated Tallusahatchee.”

26 In a separate missive to Governor Blount, Jackson reiterated the gravity of his men’s blunder: “Had there been no departure from the original order of battle, not an Indian would have escaped.” The error had cost him a quick ending to the war; the breach allowed nearly 700 Creeks to escape and forced Jackson to retreat and regroup back at Fort Strother. In an official report to General Claiborne, Jackson’s seething rage is clear: “I was compelled by a double cause—the want of supplies and the want of cooperation from the East Tennessee troops, to return to this place.”

27 His situation was most dire: his men were quite literally starving, he’d received no support or provisions, and a large number of his troops, who had been with him since the Natchez expedition clear back in January of 1813, were on expired terms—it was time for them to go home, and mumblings of discord echoed around the camp.

What happened next—a mutiny—has become a matter of controversy, the versions shedding a good deal of light on the character of both David Crockett and Andrew Jackson. In his autobiography, which contains such convincing and accurate firsthand descriptions and observations of the attacks at Tallusahatchee and Talladega that they are considered suitable historical source material, Crockett tells the story of the mutiny and highlights his involvement in it. In Crockett’s version, he and a group of volunteers, half-starved and past their enlistment dates, requested of Jackson that they return home for fresh horses and clothing, and in this way they would be prepared and rejuvenated for another campaign. Crockett notes that “our sixty days had long been out, and that was the time we entered for.” According to Crockett, Jackson denied the men their wish, but in defiance of the general they saddled up and began to depart. “We got ready and moved on till we came near the bridge, where the general’s men were all strong along both sides. . . . But we had our flints ready picked, and our guns ready primed, that if we were fired on we might fight our way through, or all die together.”

28Crockett relates how they arrived at the bridge and heard the guards cocking their guns, and through fog-thick tension the men marched on past the bridge, Jackson’s guns leveled on them: “But, after all, we marched boldly on, and not a gun was fired, nor a life lost.” As recounted, it was a defiant, dramatic, and defining act of mutiny, but it simply did not happen that way.

In fact, Crockett and his volunteer cohorts had enlisted for ninety days rather than sixty.

29 It’s true that the tattered troops were starving, destitute, and ready for home. On November 17, 1813, Jackson broke his camps and struck toward Fort Deposit, where provisions might be found. About twelve miles from camp they were met by a supply train of “150 beeves and nine wagons of flour,”

30 and the troops halted to devour meat and bread. Jackson, viewing them as sufficiently replenished, then ordered them to march straight back to Fort Strother. But the men were mentally and physically broken, and they could not take the suffering anymore. Some were verbally defiant, barking violent protestations; others merely bowed their heads in silent disdain of their commander. One company, rather than returning toward Fort Strother, turned and continued in the direction of Tennessee.

Jackson immediately mounted a horse and galloped in a long detour ahead of the deserting men. Along the way he met General Coffee and his cavalry (Crockett likely among them). Jackson ordered Coffee to fire on any men who refused orders. He sat tall and angry in the saddle, his eyes blazing with resentment and disgrace; he bellowed that he would shoot to kill any man who did not turn back.

Jackson’s fierceness must have been impressive, for the company, after very little deliberation, did an about-face, and as ordered, headed back.

31 But there was even more widespread mutiny afoot at the main encampment, and Jackson returned to find a large brigade readying to leave. His left arm still in a sling from the Benton-Carroll duel injury, Jackson used his good arm to heft up a musket and level it across the neck of his horse. He trotted to the front of the brigade and pointed it at the line of men, raging in near-hysteria that he would kill the first man to move forward. Major Reid and General Coffee eased behind in support.

Disconsolate, but realistic enough to see that Jackson and his supporters were deadly serious, the mutineers turned around and slowly, be-grudgingly, returned to their posts. The fiery, unyielding General Andrew Jackson had nearly single-handedly thwarted the mutiny, and Crockett was probably there to witness it.

Of Crockett’s entire 211-page autobiography, only the mutiny—and two small subsequent skirmishes which he records, but in which he did not participate—are thought to be intentionally falsified for political purposes. Writing in 1833, perhaps eyeing the presidency himself and certainly considering an audience that was politically educated, Crockett by this time had become nearly rabid in his anti-Jackson rhetoric, and he would have his readers see him as scathingly independent, a man not tethered to the command of another; not a party man. In reconstructing the events, Crockett clearly understood the implications of his historical past and his political future. Later, he would express this independence by pointing out that around his neck you would find no collar with MY DOG printed on it, belonging to Andrew Jackson. The fabrication of the mutiny details suggests yet again that Crockett possessed a keen awareness of how he was perceived—freewheeling, an individual and independent thinker, a man who made his own decisions and stuck by them. His “boasts” also show that he was not beyond what he must have considered a small “white lie,” a yarn or tall tale that was very much the domain of the frontier. In his recollection of the mutiny, storyteller Crockett had spun a pretty good one.

In truth, Crockett served out his full enlistment and did not depart until his official expiration on December 24, 1813.

32 But what he had seen in the command of Andrew Jackson must surely have impressed him: a steadfast resolve, an ability to lead men—with violence and fear tactics if necessary, beyond limits they thought they were capable of themselves, “a hard and determined disciplinarian.”

33 Crockett would certainly remember the man he’d seen in the fields, a leader whose

very physical appearance announced his character and personality. His face was long and narrow, his frame gaunt, indeed emaciated. But his manner radiated confidence, enormous energy, and steely determination. It bespoke a spirit that willed mastery over his damaged body. His presence signaled immense authority.

34

David Crockett had observed this man and been moved by him. He was even, perhaps, envious of Jackson, of his ability to lead, of the respect and deference he commanded, of the way others acted in his presence. It was an envy that would ultimately fester and turn to vehement hatred, a kind of poison that would come to affect and even drive his decisions in Congress, where he would one day oppose Jackson’s long-developed position on the Indians. But for the moment, Crockett would take his experiences and war-weakened body back home to Bean’s Creek. His first tour of duty was officially up; it was time to head home to Polly and the boys to see how they were keeping.