SIX

Trials on the Homefront

HOMECOMINGS WERE INTIMATE and intense times on the dangerous frontier, and the Crocketts’ would have been equally close and passionate. A new baby, little Polly (her given name was Margaret), arrived early in the year, but the bliss of her arrival was soon overshadowed by the specter of devastating loss. By summer Crockett’s wife, Polly, was gravely ill. Crockett recalled the time with anguish as “the hardest trial which ever falls to the lot of man.” Though the exact details of Polly’s death are not known, it is conceivable that she died from complications after the birth of her daughter. But myriad killers—including malaria, cholera, and typhoid—plagued the far outposts of civilization and any of these may have been the cause.

1 In any event, Polly apparently suffered for a time before, as Crockett put it with a touch of poetry, “death, the cruel leveler of all distinctions,—to whom the prayers of husbands, and even of helpless infancy, are addressed in vain,—entered my humble cottage, and tore from my children an affectionate good mother, and from me a tender and loving wife.”

Prone to almost melancholy lovesickness as an adolescent and a young man, Crockett genuinely adored his Polly, and he never spoke of her at any time with anything other than tenderness and devotion. He took the loss very hard. The event forced Crockett to ponder his own faith (what there was of it) and the divine workings of the world, which he understood are often inexplicable. Crockett described Polly’s passing as “the doing of the Almighty, whose ways are always right, though we sometimes think they fall heavily on us.” His referral to her “sufferings” suggests she did not perish overnight, or even quickly, but rather hung on and fought for a time.

2 And then, she was gone. Crockett buried Polly in the nearby woods adjacent to the cabin, marking her grave simply with a pile of rough stones, and never spoke or wrote of this trial again. Though it was summer, darkness seemed to fall all around him. Crockett languished in depression, commenting flatly that “it appeared to me, at that moment, that my situation was the worst in the world.”

The realities of frontier living, however, did not offer the luxury of moping about feeling sorry for oneself for very long. Crockett was immediately faced with a daunting fact: he was left alone with two young boys and a tiny infant daughter, and he was rather ill-prepared to care for them. The boys, at about eight and six respectively, would have been somewhat accustomed to chores and light farm work, but they were used to having a mother around, and her absence was immediately felt. The situation was bleak, as Crockett needed to try to keep the farm functioning, while hunting for food would keep him away for extended periods. It was an onerous time for the widower.

Under the circumstances, Crockett could easily have buckled, pawning his children off on relatives, but to his credit he sought other alternatives. He loved his boys, and the tiny babe Polly would certainly have reminded him of his wife. Crockett vowed to keep the family together, come what may. “I couldn’t bear the thought of scattering my children,” he confessed. One solution dawned on him, and he set about convincing his brother and his wife and children to move in and help around the place. They kindly consented, but Crockett admitted that it wasn’t ideal. “They took as good care of my children as they could, but yet it wasn’t all like the care of a mother. And though their company was to me in every respect like that of a brother and sister, yet it fell far short of being like that of a wife.”

Though throughout his narrative he is often philosophical and even poetic, Crockett was primarily a man of action, of deeds over ideas. As a young man he had “set out to hunt” a wife when he determined that he needed one, and now again he looked forward to what he must, of necessity, do. The motto to which he ultimately yoked himself (and which adorns the title page of his narrative) exclaims: “Be always sure you’re right, THEN GO AHEAD!” This was not the credo of a man who made hasty or irrational decisions, but rather reflected a man of steadfast optimism. One needed to assess a situation quickly, weigh the alternatives, make a decision, and then act on it—one needed to “go ahead” rather than retreat. There was no time to linger in the past, not when the often bitter realities of the present—hungry young mouths to feed, a farm gone to seed, debts piling up higher than the corn rows—pressed down all around you. So it was that Crockett confronted his current state of affairs and levied his decision: “I came to the conclusion that it wouldn’t do, but that I must have another wife.”

While Crockett’s first courtships were fraught with young love, acceptance, rejection, and all manner of drama, his second round could hardly even be called courting. It was more of a business venture, a contractual arrangement based on mutual needs. Nearby lived a woman recently widowed, whose husband had been slain in the attack at Fort Mims.

3 She had a son and daughter of her own, about the same age as Crockett’s children, and one can almost see him rubbing his chin as the notion hit him: “I began to think, that as we were both in the same situation, it might be that we could do something for each other.” The woman he was considering was one Elizabeth Patton, an intelligent and resourceful daughter of a prominent North Carolina farmer and planter named Robert Patton who had served in the Revolutionary War. Her good breeding showed in her manners, her managerial skills, and the tidy state of her own small farm, which appeared organized and well-tended compared to Crockett’s own grounds, unkempt because of frequent, and extended, absences. She was also rumored to possess some “grit” of her own, a sum amounting to about $800, an eye-opening and fortunate windfall certainly not lost on the perpetually impoverished David Crockett.

4 He therefore began to find reasons for visits, and as she lived nearby, this was quite convenient. He would happen by her “snug little farm” and soon began to formally pay his respects to her. She would certainly have surmised what he was up to—and appears to have enjoyed his blunt entreaties—despite his feigned subtlety: “I was as sly about it as a fox when he is going to rob a hen-roost.”

For her part, Elizabeth Patton must have seen that there might be some utility in having Crockett around, even if he hunted and spent as much time out adventuring as rumor held. There was a certain charm to the man, to be sure. At nearly thirty, and having spent the better part of his lifetime outside, Crockett had filled out into a stout, robust man of nearly six feet, with ruddy red cheeks, a swoop of thick cedar-brown hair, and piercing but playful aquamarine eyes. He possessed a beakish nose and a strong chin, set hard and determined.

5 And there were his engaging storytelling and infectious sense of humor, which made him rather irresistible. Crockett modestly recalled that his company “wasn’t at all disagreeable to her.” Ultimately, it was a match born of hardship and circumstance. “We soon bargained,” Crockett said of the union, “and got married, and then went ahead.” It was the summer of 1816.

The marriage itself, a low-key event devoid of the traditional rituals like flask-filling attendant to either of their first marriages, was presided over by Pastor Richard Calloway and took place in Elizabeth’s parents’ home in Franklin County.

6 A smallish knot of family and friends huddled quietly in the living room, where an air of seriousness and dignity prevailed. Crockett and the attendants stood still and expectant, nervously awaiting the arrival through the front doorway of the bride. Without warning, curious grunts and squeals of a pig came from outside, and almost as if herded by devious pranksters, the porker crashed the wedding party, snorting right down the aisle, its hooves skidding and sliding on the hard floor. Children joined the pig’s squeals with peals of their own laughter, and adults, previously caught up in the seriousness of the wedding, snickered. Crockett, as he often did, masterfully seized the awkward moment and made it his own. He put on a stern visage, stormed toward the pig and, grabbing it by the scruff of its neck, shepherded the unruly animal out the front door with an emphatic boot. “Old hook,” he exclaimed as he clapped his hands clean, “from now on,

I’ll do the grunting around here!”

7In the stalwart, steady, and managerial-minded Elizabeth, Crockett had found a reliable business partner, a dependable surrogate mother for his own children, and a companion, if not a soul-mate. Yet they would hardly bask in honeymoon bliss for long. In less than a year Crockett determined, as he often did when he got the itch, that the time was nigh for some exploring of new, more fertile and promising country. His farm on the Rattlesnake Branch was small and in perpetual disrepair, what would today be considered a “tear down.” Elizabeth held more acreage, a free and clear title, and combining those two, plus her substantial dowry, had potential. They might get a place big enough, with more tillable ground, to eradicate his debts and begin to see consistent profit. But it would take the right plot of ground, and that quest gave the newlywed David Crockett the perfect excuse to explore new country again. The wanderlust was in him, and perhaps feeling somewhat solvent with the staid Elizabeth taking care of things, he rallied a few of his neighbors for a reconnaissance outing. His traveling companions, named “Robinson, Frazier, and Rich,” joined him as they rode toward Alabama, heading through the Jones Valley on overgrown military wagon roads cut during the campaign Crockett had participated in, passing through the very places, like Black Warrior Town, that he had helped to burn to the ground under John Coffee. The trip, begun in hopeful search of better ground and greener pastures, started ominously and declined.

After only a day of travel, they stopped just across the Tennessee River at the home of one of Crockett’s “old acquaintances, who’d settled there after the war.” While they rested, Frazier, who Crockett referred to as “a great hunter” (quite a compliment coming from him), headed afield to hunt, but soon returned looking pale and feverish, having suffered a poisonous snake bite. Frazier was left to convalesce while Crockett, Robinson, and Rich rode on through the Jones Valley.

The expedition camped, hobbling their horses along the banks of the Black Warrior River, along a route Crockett would have found eerily familiar, having traveled it to and from Fort Mims. The horses had been tethered carelessly, for in the twilight hours before daybreak Crockett heard the team’s bells “going back the way we had come, for they had started to leave us.” Crockett waited until daylight so that he could better track the rogue equine, and volunteered to head off alone, on foot, carrying only his heavy rifle. Crockett tracked hard all day, busting through cane and thicket, wading deep swamps and creeks swirling with biting insects, flies, and swarms of mosquitoes. Crockett pushed on and on, following the ever-fainter tinkling of the horses’ bells, and confirming at each house he passed that indeed, a small group of horses had recently passed that way. Eventually Crockett couldn’t hear the animals anymore and lost their tracks, so he was forced to abandon his pursuit and determined to return to the last house he had passed, where he might rest and sup. The family there took Crockett in, and calculated that Crockett had covered nearly fifty miles on foot that day. When he awoke the next morning Crockett was deeply sore, his legs so fatigued that he feared he would not be able to walk. Still, he felt compelled to rejoin his party and apprise them of the horse dilemma, so he limped away from the safety and comfort of the house and wandered very slowly from early morning to noon, feeling progressively worse, a cold damp sweat overtaking him, his head beginning to throb and pound, his stomach and legs wambling. Finally his long rifle grew so heavy in his arms, and he had grown so feeble, that he could no longer continue, so he decided to “lay down by the side of the trace, and in a perfect wilderness, too,” to see if he might improve with some rest.

Later, like a mirage or hallucination, the image of “some Indians” hovered over him; Crockett must have wondered if they were from a dream or a nightmare as they loomed above him. The friendly Creeks offered him some ripe melons, but Crockett felt so sickly he merely shook his head without saying a word. He had spent enough time with Indians to communicate with them, and he quickly learned through their sign language something that he had half-suspected anyway: “They then signed to me, that I would die, and be buried; a thing I was confoundedly afraid of myself.” Through more sign language Crockett learned that it was about a mile and a half to the nearest house, and so he got up with their assistance and attempted to walk of his own power. “I got up to go, but when I rose, I reeled like a cow with the blind staggers, or a fellow who had taken too many ‘horns.’ ” One of the Indians proposed to lead Crockett there and carry his gun, an offer he accepted, gratefully throwing a half-dollar into the bargain. By the time they got to the house Crockett was out of his senses with fever. The woman of the house put him in bed and gave him warm teas, but he failed to improve much over the next two days. Though Crockett would not have known it, his condition was malaria, undoubtedly the result of mosquito bites he had received while walking through the bogs and swamps after his horses.

The next day some neighbors from Crockett’s home happened by—they were also out scouting new territory. They agreed to alternate horses and give Crockett a ride back up to the Black Warrior River to inform Robinson and Rich of his condition and their situation. Crockett hoped he would get better, but little did he know that his malaria was simply making the transition from the cold and hot stages to the sweating stage. As they rode, shifting him awkwardly from one horse to another, Crockett’s condition worsened; by the time they reached Robinson and Rich he slumped listlessly, no longer able to even sit the horse. Crockett did have the mental capacity to make this understated observation: “I thought now the jig was mighty nigh up with me.” He was carried to the nearest house, owned by Jesse Jones; here Robinson and Rich managed to buy horses, and left Crockett for dead.

Crockett quickly fell into cerebral malaria, flopping about in violent fits, sweating, suffering psychosis, and finally settling into a comalike state for nearly two weeks. When he came to, Crockett learned that he had been speechless for five full days, but had revived without the help of a doctor, for none was near. He later joked that at the time, “They had no thought that I would ever speak again,—in Congress or anywhere else.” Thinking he was likely to die anyway, the woman took a chance and poured an entire bottle of Bateman’s Drops (a frontier medicine containing alcohol and possibly quinine, which would have helped with the malaria)

8 down his throat, and he broke into a deeper sweat all night but then revived, and politely requested a drink of water. From that moment he was on the mend, until finally, after a great deal of effort, he was able to walk on his own. In time a passing wagoner agreed to haul Crockett in the direction of his home, and when they reached the wagoner’s destination, he rented Crockett one of his horses so he could continue the twenty miles home.

Elizabeth Crockett had lost one husband to the Creek War, and she would have been prepared for the news that David had met his end during the expedition. Such news was an unfortunate reality on the edge of wilderness. Word had come to her through Robinson and Rich that Crockett had perished. But Elizabeth Patton Crockett was thorough, detail oriented, and she wanted proof—she wanted to know about his personal effects and money, so she hired a man to head out and discover what he could. Somehow this man and Crockett missed each other on the trail, and Crockett arrived home before the man could return with the news. Elizabeth would have been shocked when she opened her door to find the emaciated and ghostly Crockett standing there, no doubt forcing a bemused grin. Crockett remembered the moment clearly: “I was so pale, and so much reduced, that my face looked like it had been half soled with brown paper.” After Elizabeth recovered from her astonishment, she informed Crockett that his traveling companions had returned his horse (they’d lucked upon all the horses on the way home) and carried with them the story that not only was he dead, but that they had witnessed Crockett take his final breath and spoken with the men who had performed the burial.

9 Prefiguring Mark Twain’s famous line “the reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated,” Crockett fashioned his own humorous understatement regarding his reported death when he said flatly, “I know’d that was a whapper of a lie as soon as I heard it!”

Crockett spent the next few months around Bean’s Creek, recuperating, doing light work, but still pondering his options, dreaming of better ground. He believed that his own farm was “sickly,” unfit to produce crops.

10 Within a year he had determined to leave it for good, and that autumn he set out “to look at the country which had been purchased of the Chickasaw tribe of Indians.” Andrew Jackson had secured in writing deals that ceded Chickasaw land in the south-central area of Tennessee, leaving it open to settlement by early 1817.

11 Crockett made it as far as Shoal Creek, some eighty miles from home, when he suffered a reoccurrence of malaria, complete with “ague and fever.” Crockett figured it was merely illness from sleeping outside on the soggy ground, but he was incapacitated and remained in that area for some time, hoping to get better. While waiting, he scouted about as he could, and he soon decided that the place was quite suitable—good enough, at any rate, to settle there for a time.

When he felt he could travel comfortably, Crockett went home to inform the family that he had found a nice spot on Shoal Creek and they would be packing up quickly for a move. By now, the Crockett clan included newcomer Robert Patton Crockett, born in 1816, plus his three other children and Elizabeth’s other two, a group of eight that would grow even larger soon enough. Over the next four years Elizabeth would be a very busy and hardworking woman, giving birth to the rest of their “second crop,” as Crockett liked to call them: Elizabeth Jane in 1818, Rebeckah Elvira (nicknamed “Sissy”) in 1819, and finally Matilda in 1821.

12 For the next two decades Elizabeth Patton Crockett would manage a household of nine children, maintain and manage the details of more than one farm, various other holdings, and small businesses involved with leasing land, all while supporting her husband’s dreams and schemes and hobbies, which came to include, in addition to his passion for hunting, a run at public office and then politics on a national scale. By any standard imaginable, Elizabeth Crockett was an amazing organizer, a tireless worker, and a fair, flexible, and lenient companion for David Crockett. It’s evident that he could not have gotten along without her. He was also conscious (if not a little self-conscious) of the power that her $800 dowry brought to his position, and he understood that with the right financial moves and business decisions, they could perhaps rise from farmer status to “planter” status over time. Crockett may have begun to sense the concept of class stratification, and that with the assistance of Elizabeth and her family, he might begin an upwardly mobile climb.

13The Crocketts sold and leased their Franklin County farms (David’s twenty acres, Elizabeth’s closer to 200) and headed for the picturesque Shoal Creek, sweet grassy pastureland and undulating hills banking gently at the clear, wide stream. They managed to find a perfect spot right near the creek’s headwaters, where they built the first of their eventual trio of cabins. Like all of his other homes, these cabins were rough-hewn and utilitarian affairs, the logs semi-peeled and prone to rot, both exteriors and interiors smallish and unadorned. But over the next six years these would suffice. The land looked fertile, the river promising—it could run a gristmill, and they would eventually own and operate a distillery for whiskey making, an iron-ore mine, and a gunpowder factory.

14 It was the closest thing to a real start that David Crockett had seen in his life. And as it would again and again for Crockett, the hope hinged on the land itself, and perhaps even more important, on the idea of the land and what it represented—freedom, the very essence of the American dream.

Their land on Shoal Creek was just a few miles from a small outpost settlement called Lawrenceburg, and an informal community was burgeoning there. Soon after the Crocketts had settled in along the creek side, in October 1817, Lawrence County was officially formed. Crockett would later describe the situation as born of necessity, saying they lived “without any law at all; and so many bad characters began to flock in upon us, that we found it necessary to set up a sort of temporary government of our own.” That “government” of sorts would have already been in the works before Crockett’s arrival, but things did move quickly once he got there. Crockett’s name was added to a list of possible candidates for the position of justice of the peace, and on November 25, the legislature appointed Crockett legal magistrate.

15 Almost by accident, and certainly without trying very hard, David Crockett had run for office and been elected, marking the fledgling stage of what would become a star-crossed career in public life.

That Crockett got selected as magistrate testifies to the solid nature of his character, since he was uneducated in the law, but rather operated from a platform of common sense and decency. Locals in the community would have known about Crockett’s recent experiences in the Creek War, noting a rough and unpolished honesty about him, an infectious straightforwardness. Crockett remembered that, while he was magistrate,

My judgments were never appealed from, and if they had been they would have stuck like wax, as I gave my decisions on the principles of common justice and honesty between man and man, and relied on natural born sense, and not on law, learning to guide me; for I had never read a page in a law book in all my life.

16

That “natural born sense” to which he refers proved to be one of Crockett’s most important character traits—he was a remarkable student of human nature, possessing savvy, moxie, and street smarts, none of which can be acquired from books or classrooms.

Crockett presided over everything from domestic squabbles to debt collection, and he quickly developed a reputation for firm conviction and fair, common sense. In a very short time he was approached by a Captain Matthews, a well-heeled local businessman and early settler whom Crockett noted sarcastically “made rather more corn than the rest of us.” As it happened, Matthews informed Crockett that he was running for the office of colonel, and wondered whether Crockett would run under him for first major in the same regiment. The fact that Matthews wanted Crockett on his ticket suggests that Crockett was already esteemed in the region.

17 Crockett at first politely declined, saying that he was finished with military matters. But Matthews was quite convincing, and Crockett reluctantly agreed, at the same time naturally figuring on Matthews’s backing in the election. Matthews then organized a great frolic and corn husking that would be part of the electioneering process, inviting the entire county along. The Crockett family arrived to find that David had been duped; Matthews’s own son was running for the office of major, the same position that Crockett had been convinced to seek. He had been set up as a patsy candidate.

Crockett took the challenge in good spirits, then turned around and took it to another level in the kind of bold and defiant move that would become his trademark. When Matthews apologetically (and perhaps insincerely) explained that his son feared running against Crockett more than any man in the county, Crockett smiled his devilish grin and told them not to fear. “I told him his son need give himself no uneasiness about that; that I shouldn’t run against him for major, but against his daddy for colonel.” Matthews, apparently a sporting man with a sense of gamesmanship, took the challenge, shaking Crockett’s hand in front of the crowd gathered to hear speeches. Crockett let Matthews finish (a tactic he would often use to his advantage, going last) then “mounted up for a speech, too. I told the people the cause of my opposing him, remarking that as I had the whole family to run against anyway, I was determined to levy on the head of the mess.” The voters obviously took to Crockett’s straight-shooting style; he came across as a common man, essentially one of them. When the tally came in, Crockett took some pride in noting that Matthews and his son “were both badly beaten.” It was a seminal moment in the political career of David Crockett, underscoring a tendency that would surface as one of his mottos: “Never seek, nor decline, office.” He was now officially a lieutenant colonel commandant in the 57th Regiment of Militia. He was Colonel David Crockett, a title he would wear proudly for the rest of his life.

That first election also defined Crockett’s “electioneering” style, one he would use again and again, partly because it worked but mostly because it genuinely reflected who he was. Reluctantly he would enter the fray, using his humor, wit, and homespun colloquialisms and charm to win the hearts of voters. He affected naïveté, and pointed out that he rarely went looking for public office but rather it periodically came calling on him, and it was his duty as a good citizen to answer the calling.

18 In most cases he was elected for positions for which he had no prior experience, and for which his résumé was spotty at best. But one of his many skills proved to be his great capacity for on-the-job training, and during his one-year tenure as justice of the peace Crockett presided over many cases, from ruling on rightful ownership of butchered hogs to child custody. He issued various licenses, including those of matrimony, “certified bounties for wolves,”

19 and as he remembered, “In this way I got on pretty well, till by care and attention I improved my handwriting in such manner as to be able to prepare my warrants, and keep my record book, without much difficulty.” Crockett thrived and learned as much as he thought he needed to in his capacity as magistrate, until he decided to resign on November 1, 1819, ostensibly to focus more on his growing industries.

For the next two years David Crockett remained essentially in one place, unusual for him given his nomadic yearnings. But there was plenty of work to be done, and he spent countless hours working on his concerns such as the gristmill, the distillery, and the gunpowder factory. Elizabeth had generously kicked in her share, but even this fell short of the amount needed to get things up, running, and producing income, forcing the Crocketts to borrow to complete the buildings. David Crockett’s growing reputation as a fair and honest man certainly didn’t hurt his ability to obtain loans, and by late October 1820 he would write one of his creditors, a John C. McLemore, explaining that he’d be able to pay him back by the following spring. He was already falling behind on his payments on two plots of ground, one just sixty acres, the other a more impressive—and more expensive—320-acre parcel.

. . . I have been detained longer than expected my powder factory have not been pushed as it ought and I will not be able to meet my contract with you but if you send me a three-hundred acre warrant by the male I will pay you interest for the money until paid. I do not wish to disappoint you—I don’t expect I can pay you the hole amount until next spring.

20His hope was that by spring his factories would be fully operational and showing profits. Things apparently worked well enough, for by early 1821 he had decided that it was time for him to take a crack at higher office, this time running for the state House of Representatives. In February he left his working industrial entities and set out on a cattle drive that took him down into the lower reaches of North Carolina, then returned to go electioneering, which, as Crockett admitted, was a “bran-fire new business” to him. He looked at it this way: “It now became necessary that I should tell the people something about the government, and an eternal sight of other things that I knowed nothing more about than I did about Latin, and law, and such things as that.” Crockett was about to take his woodsy brand of politicking to the people of Hickman and Lawrence counties, using his storytelling and sharp wit to win the people over. He would later muse about this period of his life, “I just now began to take a rise.” Things were finally settled and operating at home, with Elizabeth pretty much running the place. It was time to hit the campaign trail to see what he might roust up.

AROUND ABOUT THIS TIME there was arranged what Crockett called “a great squirrel hunt” along the Duck River, where Crockett’s kind of people—hunters, farmers, folks making a living off the land—would gather. The squirrel hunt included competition, fun, and politics, as the contest was between Crockett and his backers and those in favor of his opponent. Crockett described the setup:

They were to hunt for two days: then to meet and count scalps, and have a big barbecue, and what might be called a tip-top country frolic. The dinner, and a general treat, was all to be paid for by the party taken the fewest scalps . . . I killed a great many squirrels, and when we counted scalps, my party was victorious.

At the frolic in Centreville, the candidates were expected to speak on the subject of moving the county seat of Hickman nearer to the center, and a great many townsfolk and folk from all around the county had come for the festivities, as well as to hear what the candidates had to say on the matter. Crockett was asked to go first, and he did a fair bit of legitimate hemming and hawing, partly because in fact he had no real position on the subject, partly to play the role of the reluctant candidate, but mostly because he knew that his opponent was eloquent and “could speak prime,” and Crockett used a gambling metaphor to describe his opponent’s verbal superiority: “And I know’d, too, that I wa’n’t able to shuffle and cut with him.” But the opponent’s arrogance and overconfidence also piqued Crockett’s interest, and he was offended that the man wasn’t taking him seriously enough. Here Crockett’s insecurity and pride rose high in his cheeks. He remembered the man’s attitude: “The truth is, he thought my being a candidate was a mere matter of sport; and didn’t think, for a moment, that he was in any danger from an ignorant back-woods bear hunter.” That kind of underestimation was always a risky one to take when facing the competitive David Crockett.

Crockett’s ire was spurred, his dander up. Still, he had only made one official political speech, and his oratory skills were elementary at best. Facing the expectant crowd, he attempted to speak, but immediately became seized with stage fright: “I choaked up as bad as if my mouth had been jam’d and cram’d chock full of dry mush.” The people gawked at him as he struggled. They waited impatiently, and Crockett was at a moment of truth in his political career. He was on the verge of being laughed, then booed, right off the stump. At long last Crockett spoke, explaining his problem and seizing the instant:

At last I told them I was like a feller I had heard of not long before. He was beating on the head of a barrel near the road-side, when a traveler, who was passing along, asked what he was doing that for? The fellow replied, that there was some cider in that barrel a few days before, and he was trying to see if there was any then, but if there was he couldn’t get at it. I told them that there had been a little bit of speech in me a while ago, but I believed I couldn’t get it out.

21

The tactic worked, for as he finished the crowd roared with laughter, and Crockett quickly took the cue to tell a few more amusing anecdotes and tales, and when he had them all in stitches he politely thanked them for their time and stepped down, careful to remark aloud that he was “dry as a powder horn” and that it was a good time for them all to wet their whistles. He led most of the group to the liquor stand, where they all had drinks and Crockett continued with tall tales while his competitor was left speaking practically to himself. Crockett’s style and charisma had lured them all over to his side. His behavior and sense of humor that day became the stuff of local legend. He had won their attention and admiration, and he knew he had their votes.

He went on to the town of Vernon, where residents wished the county seat to remain. Crockett quickly comprehended a political reality—he could sway voters simply by agreeing with them. When they pressed him directly on the subject of his opinion, Crockett went coy: “I told them I didn’t know whether it would be right or not, so I couldn’t promise either way.” He had dodged the issue, at least for the moment. The next day a large gathering convened at Vernon, including his opponent as well as those running for Congress and governor, and here Crockett was asked to speak again. Crockett claimed he was nervous again, but his cleverness suggests that his jitters were contrived, all part of his scheme. The major candidates spoke “nearly all day,” likely boring and tiring the crowd with politics and posturing. Crockett said that he “listened mighty close to them, and was learning pretty fast about politics.” Seeing that the crowd was losing interest, Crockett used what he had learned. “When they were all done, I got up and told some laughable story, and quit. I found I was safe in those parts, so I went home, and didn’t go back until the election was over.”

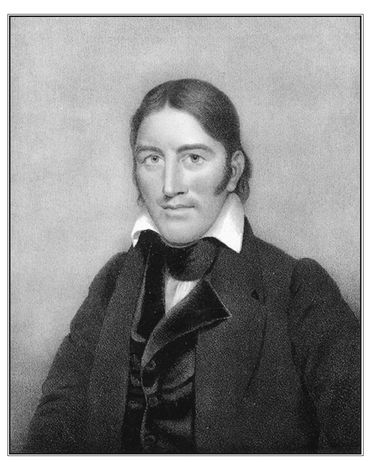

Crockett said of this portrait, “I am happy to acknowledge this to be the only correct likeness that has been taken of me.” (David Crockett. Engraving by Chiles and Lehman, Philadelphia, from an oil portrait by Samuel Stillman Osgood, 1834. Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville.)

Crockett had his first major political epiphany: that it is better to be liked, to amuse the voters and tell them what they want to hear, than it is to be knowledgeable but boring. It was a stroke of country brilliance, and it worked. When the votes were tallied, Crockett had more than doubled his competitor’s count. Colonel David Crockett had just won in his first bid for the Tennessee state legislature. The rise of Crockett, the man and the legend, had begun.