SEVEN

“The Gentleman from the Cane”

CROCKETT PACKED UP IN THE FALL and left his homestead on the banks of Shoal Creek for bustling Murfreesboro, which was the state capital at the time. His folksy wisdom, sharp and clever wit, and charismatic likability had gotten him elected, and now was his chance to take to the bigger stage of legislature, and also the relatively bigger stage of the Tennessee city. For all his later bravado, Crockett would have felt some intimidation at the transitions he was undergoing personally, professionally, and socially. Along the campaign trail he’d had the opportunity to hobnob with big-shot politicians, and he had participated at functions where his lack of social refinement would have been crudely evident. Though he would later find a way to use that “country bumpkin” image to his advantage politically, overstating his ignorance for his own benefit, at the time it would have bored into him like a tick, a constant reminder of his meager financial and social status.

Crockett relates the story of passing through the town of Pulaski on his way to Murfreesboro, and how he there met and rode with James Knox Polk, who at the time was a twenty-six-year-old lawyer from a prominent family, who had recently been selected as a clerk in the state senate. Polk looked and acted the part of the politician, and he came with real credentials, including a university education and an intimidating command of legal terminology. As they rode along “in a large company,” Polk offered to Crockett that in the coming session there might be a “radical change of the judiciary.” Crockett claims that he knew no more than his horse the words “judiciary” or “radical change,” adding a phrase that would become one of his staples, “If I know’d I wish I may be shot.” He simply smiled, agreed, and then got out of there, moving quickly away from Polk for fear that someone might immediately ask him to define the word “judiciary.” Crockett seemed intuitively to know that there were times to appear ignorant and times not to.

1 But it was always part of a ruse, and Crockett was a lot smarter than he let on. His feigned ignorance remained a ploy he would use under certain circumstances, and he could turn it on or off at will.

On September 17, 1821, Crockett presided for the first time as an elected official representing Hickman and Lawrence counties at the first session of the Fourteenth General Assembly. The very next day he found himself serving on the Standing Committee of Propositions and Grievances, as it happened his only committee appointment for the session, and a rather mundane one at that.

2 The committee addressed such issues as debt collection, land ownership, and rights of widows and divorced women, some issues Crockett would have been comfortable dealing with from his experience as a magistrate and justice of the peace.

3 Though his first term would be a relatively uninteresting, even quiet one, Crockett did manage to leave a stamp, giving an indication of his passions and beliefs concerning land issues, a passion that would ultimately define his political career. He also surfaced as an outspoken and vehement champion of the underclass, the poor, dispossessed, and disenfranchised, groups with whom he would always align himself. This inflexible political tendency would later hurt him, but at the time he was simply voting his convictions.

Land-reform questions, those which would ultimately become the Land Bill and his fixation, were of great importance to Crockett, and his initial votes reflected his ardent beliefs. Within the first week, on September 25, he voted “to release landowners in the Western District from paying double tax assessments for delinquent taxes during 1820.”

4 His voting and speaking activity over the first term concerned the public lands and land warrants, which at the time was a rather complicated situation. Squatters in Tennessee were sitting on lands which had actually been issued, as far back as the Revolution, as rewards to veterans for services rendered in battle, back when the state was part of North Carolina. So squatters, even those who had lived on plots for years, tilling the soil and building homes, could be kicked off what they believed to be their own lands if a warrant holder showed up waving a piece of legal paper. What made it worse was that many of these people had been migrating farther and farther west, constantly pushed by claimants evicting them from “their” land, until finally this population of people began to inherit the least desirable, least arable plots—rock-filled ground or scrubby, dry hills with no planting potential. Crockett understood these peoples’ plight well, for he and his family had been among them, without warrants or money, floating from place to place after each failure.

5Quite early in the session Crockett rose nervously and awkwardly to speak, and his discomfort with procedure, as well as his backwoods colloquialisms peppered his speech, marking him not only a fledgling legislator, but an untutored one. James C. Mitchell of East Tennessee stood and referred to Crockett as “the gentleman from the cane,” a moniker carrying the same connotation as “hick” or “hillbilly.” Some of the assembled chuckled uncomfortably, and Crockett immediately took Mitchell to task, demanding an apology but receiving none. Later, outside the chambers, Crockett strode up to Mitchell and lambasted him, demanding satisfaction in the form of an apology or a fistfight. Mitchell declined, assuring the raging Crockett that he’d meant no insult, but that he’d merely been describing where Crockett was from (the “cane” being what today would be referred to as “the sticks” or “the boonies”).

Crockett’s own dress at that time reflected his rural origins and his financial constraints. He wore handmade trousers and a rough shirt, a tanned-skin hunting jacket, and perhaps, for evenings out or in the legislative chambers, an unadorned wool coat. By contrast, his counterparts, having greater resources, affected the garb of the landed aristocracy: “pantaloons or knee breeches, waistcoats, cutaway coats, and shirts with fancy cuffs and cotton ruffles at their collars.”

6 Crockett’s station was obvious, even without Mitchell’s public slur. But Crockett’s wit and cunning would soon come in handy. Along the roadside Crockett chanced upon a “cambric ruffle,” the frill worn at the neck by gentlemen of the day. He squirreled it away and entered the halls, where he put it on undetected. When Mitchell next spoke Crockett waited patiently for his prey to finish, then pounced. Crockett rose to speak, the foppish ruffle garishly evident, a ludicrous ornament contrasting with his functional farm clothes. The pantomime brought the assembly to uproarious tears of laughter, forcing the embarrassed Mitchell to flee the place, and winning Crockett a modicum of respect from his peers. From that time on Crockett acknowledged the nickname “the gentleman from the cane,” on his own terms, and he wore it with pride, not only for himself, but for the backwoods folk he had come to represent.

7 Crockett had managed to win the day with his pluck and good humor, and salvage his pride in the process.

8Crockett was getting his feet wet, voting against a bill to suppress gambling, offering a speech against allowing magistrates receiving fees for lawsuits, and adapting to the lifestyle of evenings out drinking and playing at the gaming tables, when he received shocking news from home. In an act of nature eerily similar to the “Noah’s fresh” which wiped out his father and forced one of his childhood moves, a flash flood had ripped through rain-swollen Shoal Creek, scouring away the streambanks and carrying away much of the Crocketts’ industrial complex, including both the powder and gristmills. The buildings had been torn from their very foundations and swept away to oblivion. Crockett would later pun on the situation, playing off the use of “mash” in whiskey-making parlance: “The first news I heard after I got to the Legislature, was that my mills were—not blown up sky high, as you would guess, by my powder establishment,—but swept away all to smash by a large fresh . . . I may say, that the misfortune just made a complete mash of me.” At the time, it was certainly no joking matter. The disaster forced Crockett to take an immediate leave of absence. On September 29 he rushed home, expecting the worst and getting exactly what he expected. To compound matters, the distillery would also be lost, rendered useless without the ground corn churned out by the gristmill. It appeared by all measures, having just gotten started and his career on the rise, that the Crocketts were ruined.

Elizabeth Patton Crockett showed her mettle during this devastating time, shoring up her husband when he was as low as he could be. She’d been running things anyway, caring for infant Matilda and the two toddlers, Sissy and Elizabeth Jane, plus six others, getting only token help from the older boys. She had financed much of the complex and managed ably in his absence. Crockett walked the grounds in near depression, his inspection yielding news that was beyond discouraging: he estimated the losses at “upwards of three thousand dollars, more than I was worth in the world.” It was a serious moment of truth for Crockett—and his strong and honest wife advised him not to run from their troubles, but to face them head on—the way they always had. She advised that it was best to “Just pay up, as long as you have a bit’s worth in the world; and then every body will be satisfied, and we will scuffle for more.”

9 Crockett later admitted that her words were salvation for him, exactly what he needed to hear, and he agreed that the only recourse was to clear their debts and start over, embarking on yet another “bran-fire new start.” He looked at it this way: “Better to keep a good conscience with an empty purse, than to get a bad opinion of myself, with a full one.” They were noble sentiments, and suitable words to live by, and Crockett would carry both—the good conscience and the empty purse—with him to the end of his days.

The Crocketts were forced to sell off property, including the undamaged distillery and equipment, and they were sued by a number of creditors. Those creditors needn’t have worried, since when it came to repaying debt, David Crockett bordered on the obsessive. In 1811, leaving his former home in Jefferson County, Crockett had owed a man named John Jacobs a single dollar, not much of a debt, but enough for Crockett to remember. In 1821, herding a group of horses into North Carolina to sell before his next campaign, Crockett happened to pass through Jefferson, and he stopped in at the Jacobs’s place. Over a decade had gone by, and still Crockett pressed a shining dollar coin into the palm of a surprised Mrs. Jacobs. She shook her head and tried to refuse. But Crockett stood his ground on this one: “I owed it and you have got to take it,” he said.

10On October 9 Crockett returned to Murfreesboro, weary and troubled again by the uncertainties back home, burdened by the thought of packing up and moving but confident that the steadfast and stable Elizabeth could handle anything thrown her way. He needed to finish up the first session so that he could return home and help plan another move, perhaps this time to ground west of the Congressional Reservation Line, a significant demarcation separating the state into roughly two halves, with the eastern portion reserved to satisfy the preponderance of the outstanding North Carolina warrants. The western portion remained public lands, “unpreempted,”

11 effectively open for the squatting. Those lands were of special interest to Crockett, now personally (he needed land and it was free) and professionally. Lobbying for their acquisition would influence the majority of his political decisions.

He finished out the session by continuing to represent his constituents with their best interests in mind, announcing himself among his peers as a truthful man of strong convictions. He had made a few friends, including William Carroll, whom he’d first met in Vernon and early in the session voted for in the race for governor. He and Crockett had much in common, having both done battle under Jackson in the Creek War, both men self-made, of humble origins. Carroll was close with Jackson,

12 and that alignment may have influenced Crockett’s political leanings at the time; early on Crockett appeared to support the tenets that would become known as “Jacksonian Democracy”: a laissez-faire government unfettered by private restrictions, a deep suspicion of special privilege and large business, and a firm belief in the capabilities of ordinary men. Indeed, counting the Mitchell affair, Crockett had made a bit of a stir during his first session.

The assembly adjourned on November 17, and Crockett packed up what little he had and headed for what little home he had left. It was time to set out scouting again. He mustered his eldest son, John Wesley, and a neighbor named Abram Henry, and “cut out for the Obion.” The Obion River, a tributary of the Forked Deer, is large and braided, with four branches—North, Middle, South, and the southernmost Rutherford’s Fork (near present-day Rutherford, Tennessee).

13 Crockett and the boys headed west more than 150 miles to Rutherford’s Fork, and Crockett immediately liked what he saw. The place was wild, unpopulated, and thick with game. “It was complete wilderness,” Crockett said, brimming with excitement, “and full of Indians who were hunting. Game was plenty, of almost every kind, which suited me exactly, as I was always fond of hunting.” Crockett determined that here was a place he could have some elbow room, a sense of freedom, as the nearest two neighbors were seven and fifteen miles away. The land itself had character, with dense canebrakes—tangled thickets of giant tallgrass—rife with game. The rugged terrain also showed scars of the famous New Madrid earthquakes of 1811-1812, a series of quakes so violent and massive that they were estimated to be the strongest in U.S. history, each far greater in magnitude than the 1906 San Francisco quake. Referred to colloquially as “the shakes,” the New Madrid tremors caused the Mississippi River to flow backward for a time, and vibrations were felt from the Rocky Mountains to the Atlantic Coast and from Mexico to Canada.

14 The epicenter of the quakes was at New Madrid, Missouri, in close proximity to Tennessee and Kentucky, and after the first monster quakes, aftershocks would rock the region intermittently for a full seven years in the most dramatic geological upheaval ever witnessed in North America, putting a genuine and continous fear of God into the inhabitants.

Prior to the quakes, Reelfoot Creek flowed through the low-lying area and into the Obion River, but when the terrifying shakes had finally finished rumbling they’d left the eighteen-mile-long Reelfoot Lake in their wake, a huge slurry of water five miles wide and twenty feet deep in places. Violent and persistent storms ravaged the area in the aftermath of the quakes, razing entire forests, rending enormous caverns in the earth, filling the sky with a thick pall of steam, debris, and gas. Crockett referred, almost reverently, to the devastated area as a “harricane,” and the thickets, choked by abundant regrowth of native and competing Southern grass and giant cane, some well over head high, provided ample cover and abundant food for ground-dwelling creatures.

15 The result of this upheaval, this tangle of forest and cane, were the game-filled canebrakes Crockett loved to haunt. Here he would sharpen his already considerable skills as a woodsman and a hunter, here where life made sense to him, where he reveled in the simplicity of the hunt, of moving at the pace of wild things.

Crockett became enamored with the landscape and he staked a claim on a spot that looked suitable, then figured that while they were there they might as well hunt.

16 They first rode out to visit a man named Owens who lived across the Obion. The river was near flood stage, fairly bursting and painfully cold, but in they waded anyway “like so many beavers.” The going was treacherous, the bottom dropping out from under them at times, Crockett carrying a long pole that he used to feel the river bottom in front of him. Tromping through murky sloughs, Crockett used his tomahawk to fell small trees to fashion into bridges for the deepest sections. More than once John Wesley resorted to swimming, becoming soaked and bitterly cold. Finally they trudged ashore on the far banks, John Wesley shivering and shaking “like he had the worst sort of an ague.” They struck for a nearby house, pleased to be greeted by Mr. Owens and some other men, who led the cold and waterlogged travelers inside.

Crockett and his cohorts warmed by the fire, Owens produced a bottle of whiskey. Crockett concluded at that moment “that if a horn wasn’t good then, there was no use for its invention.” Crockett slugged down half a pint, then passed it on to his boy John Wesley, and they all started to feel better and dry out. Mrs. Owen tended to John Wesley, drying his soaked woolens and plying him with more liquids and some hot food. Crockett accepted an offer to join a run that the men were taking up the Obion, and he and Abram Henry boarded a boat with Mr. Owens and the crew, who had loaded it with “whiskey, flour, sugar, coffee, salt, castings, and other articles suitable for the country.” They had struck a deal to deliver these goods upriver at McLemore’s Bluff, on the South Fork, for five hundred dollars. Crockett remembered the boat party fondly: “We staid all night with them, and had a high night of it, as I took steam enough to drive out all the cold that was in me, and about three times as much more.”

The next day Crockett decided to tag along for the boat trip, and they proceeded upriver until they came to a logjam of downed timber caused by the shakes; the river was too low to be navigable, and they returned to the Owens’s place to wait for some higher water. Though it rained, as Crockett put it, “rip-roriously” the following day, the river was still too shallow to accommodate the heavy boat, so Crockett used his charm and gregariousness to convince the boat owner and all the crew to head out to his new claim where they “slap’d up a cabin in no time.” Crockett bargained for some provisions, too, putting up in stores “four barrels of meal, one of salt, and about ten gallons of whiskey.” The cabin was simple and crude, just a rough-hewn shelter with stone fireplace and straight front porch, but it would do for the moment.

17The deal he made for the provisions required that Crockett hire on as boat crew for the trip to McLemore’s Bluff, and so after killing a nice deer and bartering for “a large middling of bacon,” he left John Wesley and Abram Henry at his new cabin and headed upriver with the boatmen. He figured he’d be gone six or seven days if things went well on the river. They made camp that night below the fallen timbers, and the next morning at first light Crockett headed out hunting along the shores, thinking the men would be unable to get the boat through the jams and debris that day. He crept quietly along in his knee-high leather hunting moccasins, tracking deer and elk and bringing down two bucks before midday, stopping to hang them in trees to keep predators from absconding with them, and marking the spots to retrieve them later. He stalked all day and into the early evening, noting the time by the long slants of shadow through the thick growth, dropping and hanging six deer that day and then bursting through the bramble to the place he figured the boat would be. After hollering and receiving no reply, Crockett fired his rifle, and the shot the boatmen fired back echoed unsettling news; they had made it through the jammed timber and were well ahead, some two miles upriver.

By now it was dark, but Crockett’s only choice was to make his way toward the boat, scrabbling over and under nearly impenetrable thicket: “I had to crawl through the fallen timber . . . for the vines and briers had grown all through it, and so thick, that a good fat coon couldn’t much more than get along.” He moved along this way slowly, the thorns tearing away at his clothes and flesh as he hollered for the boat, and at last they came back for him in a skiff. Crockett was so sliced up from the ordeal that he felt as though he “wanted sewing up all over,” and so beaten by fatigue that he could hardly move his jaws to eat his first sustenance in twenty-four hours. In the morning Crockett took a man with him to fetch most of the deer he had hung (leaving a couple to possibly retrieve later), then returned to the boat, and finally, after slow going and some difficult maneuvering, they landed at McLemore’s Bluff on the eleventh day.

Their work on the boat completed, Crockett was given a skiff from the captain and his men as a present, and he also took with him a young crew man named Flavius Harris, hiring him on to help get the new farm under way.

18 Crockett and Harris made a speedy return downriver, then, along with John Wesley, began the difficult duties of getting his new homestead ready for the rest of his family to live in. “We turned in and cleared a field, and planted our corn, but it was so late in the spring, we had no time to make rails, and therefore put no fence around our fields.” It was by now the spring of 1822, and Crockett needed to get back to Elizabeth and the other children. First, he wanted to hunt some more and put up more dried meat, so after planting what they considered a sufficient amount of corn, Crockett took to the woods and mountains and river, awed by the wildness and remoteness of the place. “In all this time, we saw the face of no white person in that country, except Mr. Owens’ family, and a very few passengers, who went out there looking at the country. Indians, though, were still plenty enough.” Hunting hard and expertly, he managed to kill ten bears “and a great abundance of deer.”

His crop “laid by,” loads of dried bear and venison and other provisions put up to store, Crockett reluctantly headed home the 150 miles to Shoal Creek. He knew that things were in disarray there, and he had made some preparations in advance of his scouting departure, including finding temporary housing for Elizabeth and the children, since they lost their homes after the gristmill disaster. During his absence a number of suits had been brought against him, with a couple of judgments granted, and Crockett’s happy homecoming was peppered with despair. Perhaps the worst was arriving to discover that two men, Rueben Trip and Thomas Pryer, had moved in and now occupied his home.

19 Despite knowing that it was likely to happen, the concrete evidence of his own failures must have stung Crockett’s considerable pride. Just as Crockett and John Wesley rejoined Elizabeth and as he and Elizabeth began dealing with their legal and situational issues, Crockett received news on April 22, 1822, from newly elected Governor William Carroll that the second session of the legislature would convene on July 22. This would give the Crocketts just enough time to clear their debts, get all their affairs in order, and prepare to leave for Rutherford’s Fork when he returned from the second session. Elizabeth would once again take on the significant burdens at home, but to Crockett’s great relief, she did so without complaint.

In his second go-round as a legislator, Crockett took to his work with a sense of duty and fairness. His votes were those of a man concerned with social equality and justice, as when he introduced a bill to provide relief for a black man named “Mathias, a free man of color.”

20 He opposed bills that would undermine the prevention of fraud in the execution of last wills and testaments, as well as those that would take rights away from widows and their children.

21Crockett’s other concerns during this time included the Tennessee Vacant Land bill, a foreshadowing of the contentious issue that would eventually consume him. The bill, in brief, asked representatives to authorize the legislature of Tennessee “to dispose of the vacant and unappropriated lands, lying to the North and East of the Congressional Reservation Line, at such price as may be thought prudent by said legislature, for the purpose of education.”

22 David Crockett, primarily self-taught, may have already been somewhat dubious of acts structured to raise money for state-funded education, the learned and privileged being two groups he would come to despise and feel threatened by. His voting record during this term illustrates an interesting blend of equanimity and self-interest: he agreed that vacant lands should be put on sale at the lowest possible prices, prices the poor (which included himself ) just might be able to afford. He also voted on August 20 for a bill designed chiefly to promote the construction of ironworks.

23 Given his recent (if failed) dabbling in mills, distilleries, and the gunpowder factory, Crockett appeared to remain intrigued with the potential of such industries and wished to protect them, even garnering governmental support for such entrepreneurship. He managed to get himself placed on a select committee to consider a loan to Montgomery Bell for a “Manufactory and works.”

24 Crockett may well have been considering another go at manufacturing once they got relocated.

The short second session adjourned on August 24, and Crockett went home immediately and wasted no time collecting his family and striking out to his new claim on Rutherford’s Fork. “I took my family and what little plunder I had,” Crockett recalled, “and moved to where I had built my cabin.” It would have been a long, slow, cold, and uncomfortable 150-mile trek, burdened as they were with belongings and young children. They arrived in the Obion country in late October 1822. Crockett’s hired man, Flavius Harris, had kept things in order, and Crockett and the boys helped to bring in the last of the corn crop they’d planted the previous spring. Once settled in the cabin, Crockett grew excited about the hunting opportunities again. The region he had chosen could not have been any richer in game, any more suited to his favorite pursuit. “I found bear very plenty, and indeed, all sorts of game and wild varmints.” He hunted hard and long all autumn and into early winter, filling his larder with venison and fowl, and though still far from financially flush, he would have been somewhat content with the knowledge that he was providing for his family. He had to resort to selling wolf hides for any real income during the difficult early transition to the Obion country.

Just before Christmas 1822, Crockett ran out of the gunpowder he needed for hunting, but also necessary for the tradition of firing “Christmas guns,” a common regional celebration. Crockett remembered that a brother-in-law, who lived on the opposite bank of Rutherford’s Fork some six miles west, had brought him a keg of powder but Crockett had yet to bring it to his own house. Despite the biting-cold temperatures and recent winter storms, Crockett determined to go after the powder. He later admitted that it was a foolhardy undertaking, with the river over a mile wide in places he’d be forced to ford. The more sensible Elizabeth argued vehemently that he should not attempt such a journey under these circumstances, but Crockett explained that they needed the powder since they were running out of meat. Elizabeth pointed out that they might just as well starve as for David to “freeze to death or get drowned,” either of which was likely if he went. Stubborn as always, Crockett dressed in his thickest and warmest “woolen wrappers,” and moccasins, tying up a dry set of “clothes and shoes and stockings” and against Elizabeth’s entreaties, off he went into the cold, snow swirling around him and collecting in deep drifts. He would later concede that it was a questionable idea, adding that “I didn’t before know how much any body could suffer and not die. This, and some of my other experiments with water, learned me something about it.”

Crockett plowed through ankle-deep snow until he reached the river, which gave him pause: “It looked like an ocean,” he remembered, and was frozen over, glazed with a thin veneer of ice. Undaunted, he waded right in and crossed a long channel, walking in places over downed logs until he came to a large slough, all the while holding his gun and dry clothes above his head and out of the water. Logs he remembered crossing while out hunting were now submerged, and he was forced to wade armpit-deep, then nearly neck-deep. Then he cut saplings to lay down and crawl across sections too deep to wade. He began to lose feeling in his feet and legs, and after crossing a small island in the river he came to another slough, this one spanned by a floating log he figured he could walk over. The log bobbled in the freezing stream and about halfway across Crockett lost his balance and the log rotated, tossing him and completely submerging him. He hurried as much as he could and fought his way to the higher ground, all his limbs now nearly useless as he pulled off his wet clothes right there on the stream bank and struggled frantically into his dry kit. “I got them on,” he recalled, “but my flesh had no feeling in it.”

He understood the dire nature of his situation, and knew that getting warm was his only way out. He attempted to run to get some blood pumping, but “couldn’t raise a trot for some time.” He staggered on, zombie-like, unable to step more than one foot forward at a time, and in this way he lurched and limped five miles to his brother-in-law’s place, near-dead and dreaming of fire. It was growing dark when he finally knocked feebly on the door, and the family let him in and warmed him slowly back to life in front of the fire and gave him horns of whiskey. The next day dawned bitter cold, snow drifts blowing into cornices along the river, and Crockett agreed to wait out his return. He knew that the river would be freezing over, but doubted its ability to bear his weight. Crockett used the down time to hunt, killing two deer for his in-laws, and the next day chasing after a “big he-bear” until nightfall but failing to bag him. Finally, on the third day, though it remained painfully cold, Crockett decided that he had to get back to his family, who were without food. He “determined to get home to them, or die a-trying.”

The river had frozen over more completely, but as he had feared, not solidly enough to hold him, and before long he had broken through the ice up to his waist. He wielded his tomahawk as an icebreaker before him, hacking as he pushed on. Intermittently the ice would bear his weight, and he crawled those frozen distances until he broke through again, completely submerging himself but holding the powder keg dry above the water. He was now partially frostbitten, clearly hypothermic, and bordering on delirious, and he knew he was in trouble:

By this time I was nearly frozen to death, but I saw all along before me where the ice had been fresh broke, and I thought it must be a bear straggling about in the water. I therefore fresh primed my gun, and, cold as I was, determined to make war on him, if we met. But I followed the trail until it lead me home, and I then found out it had been made by my young man that lived with me, who had been sent by my distressed wife to see, if he could, what had become of me, for they all believed I was dead. When I got home I wasn’t quite dead, but mighty nigh it; but I had my powder, and that was what I went for.

25

Though Elizabeth was understandably growing weary of his stubbornness, his near-death experiences, and the constant threat of losing a second husband, she also knew that he had to hunt, both for himself and to keep them in food and furs. Crockett would have measured his own self-worth in part by his hunting prowess, and the very next day he set out for bear, responding to a dream he’d had about a violent battle with one, and viewing it as a sign, adding that “In bear country, I never knowed such a dream to fail.”

He went to likely ground “above the hurricane,” taking with him three dogs, and heading six miles down Rutherford’s Fork and then some four miles over to the main Obion. Sleet drove down in heavy slants across the iron-gray skies, and “the bushes were all bent down, and locked together with ice,” making the going cold and difficult. He was soon warmed by the flush of gobbling turkeys, and he brought down two of the largest, and slung them heavily over his shoulders and continued crashing through the cane. Eventually the birds grew too heavy to carry so he stopped to rest, and just then his oldest hound sniffed about a log, then raised his head to the sky and hollered out baying. Then he bolted, and the other dogs followed, with Crockett running hard behind, the turkeys a mass of feathers and wings and necks dangling and swaying. Soon the dogs were well out of sight, and Crockett could only follow the faint sounds of their barking and baying deep into the thickets.

He finally found them barking up a tree, and he laid down his turkeys and readied to fire on the bear, but when he looked up there was nothing there. The dogs bolted, and when he caught them they were barking up an empty tree again, and he grew so frustrated he vowed to pepper the dogs with shot the next time he got close enough, figuring they were baying at the old scent of turkeys. He ran hard to catch them and finally reached a break in the cover, a big open meadow, and up ahead of his dogs he saw “in and about the biggest bear that ever was seen in America.” The bear was so big and black and frightening that it resembled an enraged bull, and Crockett understood that he was so large that the dogs had been hesitant to attack him, which explained their curious behavior. Crockett quickly hung the gobblers in a nearby tree, and, flushed full of adrenaline, he “broke like a quarter horse after my bear, for the sight of him had put new springs in me.” By the time he managed to get near the dogs and the escaping bear they had entered a deep thicket, and Crockett was slowed to a crawl, as the stuff was too low and tangled to walk through.

Finally, Crockett broke through to see the bear ascending a giant black oak, and he scrambled to within eighty yards of the enraged but frightened creature. Breathing heavily with a mixture of fear and excitement, Crockett primed his rifle, leveled on the great black bear’s breast, and fired. “At this he raised one of his paws and snorted loudly.” Crockett knew full well that a massive black bear, angered and injured, was an extremely dangerous animal, so he reloaded as fast has he could, aimed once more, and fired. “At the crack of my gun he came tumbling down, and the moment he touched the ground, I heard one of my best dogs cry out.” Crockett brandished his tomahawk in one hand, a big butcher-knife in his other, and ran to within a few yards of the bear, which then released his dog and cast his wild eyes on Crockett. Crockett backed off, grabbed his gun again, loaded nervously and quickly, and put a third ball in the bear, this time killing him.

Crockett slumped down and surveyed the bear and could not believe the size of it. He’d need help getting him out of there for sure, so he left the bear and “blazed a trail,” cutting saplings as he went to show him the way back. He arrived home and enlisted his brother-in-law and another man to go with him to bring in the bear. Returning to the kill at dark, they built a fire and butchered the animal. Crockett reckoned it was the second largest bear he ever killed, weighing about 600 pounds, and by now, warmed by the fire and the blood lust of this kill still in his throat and mouth, the trek to retrieve his gunpowder seemed justified. He also noted with some humor, using a phrase he might well have coined, that “a dog might sometimes be doing a good business, even when he seemed to be barking up the wrong tree.”

Crockett devoted the remainder of that winter to the canebrakes, hunting long hours with his dogs and neighbors and occasionally making the forty-mile trek to Jackson to sell wolf, deer, and bear hides for the few dollars they would bring. And while his family needed any extra money his hunting could generate, his prowess afield transcended monetary value: on the frontier, one’s self-worth was measured by one’s ability in the hunt, in what a man could bring down with his gun—whether animal or enemy, and in the field, and as a marksman, David Crockett was peerless. Crockett was becoming not just a formidable hunter but a legendary one, and he would later boast of killing 105 bears in less than a year. Many of the pelts he sold, and much of the meat he used, or shared with family and neighbors. Far and wide throughout the South through the frontier grapevine of storytelling his name became synonymous with successful backwoods life. These bear-hunting tales followed the ancient storytelling motif in which the hero confronts a life-threatening adversary and slays it. His own tales of these adventures illustrate a finely tuned skill, the tall tale, the hyperbolic boasting demanded of the hunter and the hero.

26 He may have been only vaguely aware of it, but David Crockett was in the process of manufacturing the myth and legend that would live long after him.

Crockett’s hunts proved so successful that winter that by February, as he put it, he “had on hand a great many skins,” and he set out with John Wesley for Jackson, where he sold the hides and did well enough (wolf “scalps” going for three dollars apiece at the time) to purchase provisions, like sugar, coffee, salt, and more lead and powder for hunting, that might take him through to spring. While in town, Crockett ran into a few of his soldier friends from the war, and he decided that rather than return straight away, he’d take a few horns with the boys.

While whooping it up in a local tavern, Crockett became acquainted with three legislative candidates, among them a Dr. William E. Butler, a nephew by marriage to Andrew Jackson. With Butler were Duncan McIver and Major Joseph Lynn, and the three of them would be running against one another in the coming election. Dr. Butler was, among other things, the town commissioner of Jackson; he was quite influential in the area, especially given his connection to General Andrew Jackson. McIver had been among the earliest settlers in the area, and all three men were known politicos, men of high standing and notoriety in the region.

27 During the course of the evening it was suggested, in what Crockett suspected was a joke against him, that he ought to run, too. Crockett pointed out that he lived “forty miles from any white settlement, and had no thought of becoming a candidate at the time,”

28 and the next day he and John Wesley headed home.

Just a week or two later a friend arrived at Crockett’s house with a copy of the Jackson Pioneer, which contained an article that announced Crockett’s candidacy. Crockett immediately assumed, his insecurity flushing his cheeks even redder than they usually were, that he was being made fun of, and he said as much to Elizabeth: “I said to my wife that this was all a burlesque on me, but I was determined to make it cost the man who had put it there at least the value of the printing, and of the fun he wanted at my expense.” Riled and testy, Crockett hired an able young farmhand to help Elizabeth, and he set out electioneering, discovering quite quickly that his reputation preceded him. People were talking of Crockett the bear hunter, even referring to him reverently as “the man from the cane.”

Butler, McIver, and Lynn were politically savvy, and they understood that they’d have a better chance working together than running against one another, so in March they held a caucus to decide which of the three would be best suited to oppose Crockett, settling on Dr. Butler as the man for the job. That Butler’s wife was Andrew Jackson’s niece likely played some role in the decision, but Butler was also well educated, articulate, and had the money to sustain a serious campaign. Crockett later admitted that it would be a tough race, and that Butler was a smart and worthy opponent: “The doctor was a clever fellow, and I have often said he was the most talented man I ever run against for any office.” Knowing the odds he was facing, Crockett would have to resort to the most creative campaign tactics he could summon, playing off his affability, his growing reputation as a backwoods character, and his uncanny ability to give voters exactly what they wanted to hear. He determined to exploit his authenticity as a man of the people against his opponents’ aristocratic background, hoping the people would be able to relate to him more easily than to Butler.

Crockett’s first solid opportunity came at a political rally, where Colonel Adam Alexander happened to be campaigning for national Congress. Crockett was in attendance, and he saw that Butler was, too. Crockett relished innocent chicanery, and in the large assembly of people he saw his chance. After Alexander was finished speaking he introduced Crockett to a few folks, explaining that Crockett was running against Butler. People began to mill around, their curiosity piqued to see the bear hunter. Finally Dr. Butler also recognized Crockett, and he seemed surprised to see him there. “Crockett, damn it, is that you?” he asked quizzically.

A master of comic timing, Crockett took the cue and ran with it. “Be sure it is,” he answered, grinning at his now substantial audience and launching into character, laying the backwoods drawl on thick as molasses, “but I don’t want it understood that I have come electioneering. I have just crept out of the cane, to see what discoveries I could make among the white folks.” By now, people were chuckling, fascinated by Crockett and his antics. Crockett kept right on, explaining to Butler exactly how he would defeat him:

I told him that when I set out electioneering, I would go prepared to put every man on as good a footing when I left him as I found him on. I would therefore have me a large buckskin hunting-shirt made, with a couple of pockets holding about a peck each; and that in one I would carry a great big twist of tobacco, and in the other my bottle of liquor; for I know’d when I met a man and offered him a dram, he would throw out his quid of tobacco to take one, and after he had taken his horn, I would out with my twist and give him another chaw. And in this way he would not be worse off than when I found him; and I would be sure to leave him in a first-rate good humor.

29

Dr. Butler had to admit that such a tactic would be very tough to beat. Crockett conceded that in terms of campaign funds, they were certainly not on equal footing, so he would do what he knew how to, using his backwoods skills and ingenuity. With the audience hanging on each new and outrageous sentence, Crockett cited his own industrious children and coon dogs, which he would employ every night until midnight to raise election funds, and that he himself would “go a wolfing, and shoot down a wolf, and skin his head, and his scalp would be good to me for three dollars . . . and in this way I would get along on the big string.” The antics had the crowd in stitches, and though the clever Crockett had claimed not to have come electioneering, that’s exactly what he had done, selling his infectious personality to the voters.

Crockett employed similar stratagems and more in the official electioneering, taking advantage of the generous and fair Dr. Butler whenever he could. Butler admired Crockett’s spunk and appeared to enjoy competing with him; he even sought out his company. Once, hearing that Crockett was in Jackson on the campaign trail, Butler invited him to his home for dinner. Crockett accepted, and when he arrived he could not help but notice the finery, the lovely furnishings, and especially the floor rugs to which Crockett was unaccustomed. The rugs on Butler’s floors were so fine that Crockett felt guilty even stepping on them, and he made an exaggerated point not to, hopping over them when he entered to dine with the Butlers. Deviously, Crockett used this episode in later stump speeches, relating the dinner episode to the people: “Fellow citizens, my aristocratic competitor has a fine carpet, and every day he

walks on finer truck than any gowns your wife or your daughters, in all their lives, ever

wore!”

30 In this way Crockett undermined his opponent and continued to parade himself as a man of the people.

Opponents often traveled together, coming into towns together and giving speeches one after the other. As this went on for some time, candidates came to know each other’s speeches nearly as well as their own. Though Crockett preferred to follow, offering up a comic anecdote and leaving the listener wanting more, once near the end of the campaign he took the opportunity to go first, and with devilish premeditation, he delivered Dr. Butler’s own speech almost verbatim. It left the good doctor with literally nothing left to say on that occasion, and Crockett’s coup became the talk of the town.

31 David Crockett had found his stride, and expressions that the people understood flowed off his tongue as he entertained them. He promised them that he would “stand up to my lick log, salt or no salt,” and he did. When the votes were tallied, Crockett had won by 247 votes. The reluctant candidate, forced to run to save face, was heading to Murfreesboro once again. Though he would employ false modesty in calling this victory luck, he must have sensed his developing expertise in getting himself elected. He was a showman, a born orator with an uncanny sense of comic timing, and he understood intuitively the principle that most fine entertainers come to live by: “Leave ’em wanting more.”

Crockett arrived back in Murfreesboro for the Fifteenth General Assembly, which convened on September 15, 1823. By now he would have been fairly comfortable with the town and environs, and with the routines involved in life as a state legislator. He had even gained a degree of respect among his colleagues, for his campaign practices were by now well documented, related at taverns and even in the assembly halls. And although as a campaigner David Crockett assumed the guise of a prankster, as a sophomore legislator he took his role seriously, bearing the added responsibility of representing five new counties—Madison, Carroll, Humphries, Henderson, and Perry. There had been, as yet, no constitutional convention, so his own district was not equally represented, but the fast formation of new counties clearly illustrates the significant migration into the region and the prodigious growth spilling into the West.

32 By the end of the session the district would swell to ten new counties.

Crockett’s first week back on the job was frenetic. He immediately found himself on three significant committees, one having to do with specifying new county boundaries, one on military affairs, in which he had at least some experience and interest; and the last having to do with vacant lands, the one to which he would devote most of his attentions.

33 Crockett quickly had the opportunity to assert his growing independence, an independence that would become a kind of contrary trademark and that would eventually be his political unraveling. That independence also signaled his first public and definitive rift with Andrew Jackson, a schism which perhaps began as far back as the Creek War, when Old Hickory quelled the attempted mutiny. Crockett later looked back at the Fifteenth General Assembly with this salient recollection: “At the session in 1823, I had a small trial of my independence, and whether I would forsake principle for party, or for the purpose of following after big men.” Principles, voting one’s conscience, being true to self and constituents—these were all tenets Crockett cared very much about. Often such idealism—and inability to compromise—hurt him politically.

The test of independence to which Crockett alludes had to do with the election of a United States senator. The term for Senator John Williams had recently expired, and he sought reelection. Around the assembly halls and in the local taverns it was no secret that Williams and Jackson had open enmity dating back to the Creek War. It was also common knowledge that the political machines of Tennessee were priming Jackson to be president. As the senate vote neared, Williams looked like a shoo-in, so much so that in the end Jackson, against his initial interests, agreed to run, fearing that his party’s chosen opposition candidate, Pleasant M. Miller, was unlikely to defeat the incumbent. The race was far too close for comfort, with Jackson prevailing by a mere ten votes, and illustrated just how divided the legislators were.

34 Crockett had until this time been openly amenable to Jackson and especially to the idea of his presidential candidacy that would be forthcoming, but he voted for Williams, noting that Williams had been successful and done a good job the last time around, and therefore there was no good reason to discharge him: “I thought the colonel had honestly discharged his duty, and even the mighty name of Jackson couldn’t make me vote against him.”

It is unclear whether Crockett had other motives for voting against the tide, and against Jackson. It may have been as simple as personality traits, with Crockett beginning to sense that Jackson was moving away from the common man and would be no friend when it came to the western land issues. Crockett was already deeply suspicious of men with money and vast land holdings, and he would certainly have known that while Jackson liked to play on his “self-made” status, they were not on equal footing. By 1798, Jackson owned more than 50,000 acres in central and western Tennessee, much of it worth more than ten times what he had originally paid.

35 Crockett was unapologetic, even downright prideful, about how he voted, though he admitted that the decision was unfavorable politically. He later assessed his first public breach with Jackson in this way: “But voting against the old chief was found a mighty up-hill business to all of them except myself. I never would, nor never did, acknowledge I had voted wrong; and I am more certain now that I was right then ever.”

As it turned out, though he was victorious, Jackson later declined the office—he had only intended to run and win, and that was enough to keep Williams out of the position. Jackson had succeeded in ridding himself of Williams as a political thorn in his breeches. Crockett summed up his sentiments on his vote by adding, “I told the people it was the best vote I ever gave; that I had supported the public interest, and cleared my conscience in giving it, instead of gratifying the private ambition of a man.” He would be his own boss even if there appeared to be very long and helpful political coattails to ride on. He was having none of it. He did what he believed was right and stuck to his guns, exhibiting an obstinate, unyielding nature that wasn’t entirely suited to partisan politics.

David Crockett was in the process of establishing his political tendencies, but also his persona: he would be a man of the people and for the people. He would back any bills or resolutions that were conceived to assist those people with whom he could relate, with whom he felt fraternity, even kinship. Interestingly, James Polk voted with Crockett twice during the session, including on a petition to hear no divorce proceedings— Crockett was actually in favor of the legislature paying the legal expenses in such cases so that the poor would have fair and affordable access to lawyers. Crockett came out in opposition of using prison labor on state construction projects like roads and improving the navigation of rivers, suspicious as he was of authority and mindful that some of the inmates would have been incarcerated simply for being indigent and unable to pay their bills.

36 In fact, quite early in the session Crockett put forth a bill that would entirely eradicate imprisonment for debt, if that debt could be proved “honest debt.” Mindful of the fiscal pains people in the region still felt from the depression of 1819, Crockett aligned with the majority vote to reduce state property taxes, again in an effort to assist the impoverished. In a curious and ironic vote, especially given his own penchant to campaign using the “plug and a dram” technique of luring voters to the liquor stand, and plying them with horns of spirits and twists of tobacco, Crockett voted to prohibit the sale of liquor at elections. Crockett also presaged a later interest in (and deep suspicion of ) banking issues, favoring a move toward the state bank of Tennessee and local branches that might provide loans to farmers in need.

37 Crockett had previously spoken outwardly, and scathingly, against the current banking system, and was quoted in the

National Banner and the

Nashville Whig in September of 1823 as saying that the “Banking system [was] a species of swindling on a large scale.”

38The land issue arose again in the form of the North Carolina land warrants, with North Carolina University presenting a large number of warrants of veterans (by now deceased) and requesting authorization to sell them in Western Tennessee as a fundraising technique for the growing university. The North Carolina warrants had the potential to displace untold numbers of squatters; Crockett smelled a rat. He had his own claim on the Obion, and he believed that folks like him deserved the right to buy their land first, before outsiders with dubious warrants. A division within the Jackson supporters had occurred over this issue, with Felix Grundy supporting the presentation of North Carolina warrants, and the savvy legislator (and future president) James Polk in opposition. Crockett initially aligned with Polk, but later broke with him, believing that it was a mistake to allow outsiders in the form of North Carolina residents to come in and purchase vacant lands for cash—the poor would once again be priced out.

39 Crockett preferred that the land be sold to those who lived on it, on credit, rather than be bought and used as speculative real estate by outsiders. Crockett’s position garnered him a degree of public notoriety when it appeared in the

Whig:

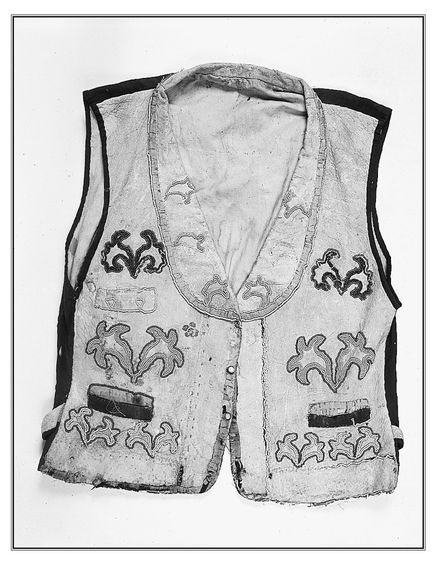

Crockett’s spangled, three-pocket buckskin vest reveals a man with a sense of style. The glass beadwork is colorful and attention-getting, just like his character. (Crockett vest—color transparency. Courtesy of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library, San Antonio.)

Mr. Crockett called up his resolution relative to land warrants . . . He had heard much said here about frauds, &c., committed by North Carolina speculators; but it was time to quit talking about other people, and look to ourselves. This practice was more rascally, and a greater fraud, than any he had yet heard of . . . The speculators then preferring to be great friends to the people in saving their land, had gone up one side of the creek and down the other, like a

coon, and pretended to grant the poor people great favors in securing them occupant claims—they gave them a credit of a year and promised to take cows, horses, &c., in payment. But when the year came around, the notes were in the hands of others; the people were sued, cows and horses not being sufficient to pay for securing it. He said again, that warrants obtained this way, by the removal of entries for the purpose of speculation, should be as counterfeit as bank notes in the hands of the person who obtained them, and die on their hands.

40

By the end of the session Crockett had turned over a good number of political cards—most revealing that he would vote his conscience come what may. He’d outwardly broken with Jackson, and with Polk as well, when Polk favored the sale of public land to raise money for universities. Crockett understood too well that universities were the domain of the privileged, so subsidizing land-grant institutions was of no interest to him. By now his name and position on such matters were getting out into the regional papers, developing his reputation as a representative of the poor and downtrodden. It was a role Crockett played well.