EIGHT

“Neck or Nothing”

CROCKETT’S MODEST SUCCESSES in the last session whetted his appetite for politics enough to convince him that a run at Congress was a reasonable next step. He had now begun to feel a modicum of comfort moving in the elite circles of Murfreesboro, playing on his persona to win voters and using his contrary nature to stir things up in state politics and get himself noticed. Elizabeth would have been very happy to have him home, as his hunting skills were responsible for their food. The pressure to provide was increased by the lease of an additional tract of land on the Obion, and coupled with the hunting were the need to continue tilling, planting, and harvesting viable crops for vegetable sustenance, which Crockett oversaw in a rather distracted way, leaving much of the toil to his boys and few hired hands. He would always prove a very reluctant farmer, much preferring the chase, whether for wild animals or public office.

Crockett later postured that he was coerced into his first congressional race, again against his wishes and better judgment, but that others urged him into the fray. Colonel Adam Alexander was then representing the western district, which now numbered eleven counties, and though he possessed significant power and influence, and was a wealthy planter and extremely well-connected, he had blundered in his previous term by voting in favor of high tariffs, leaving his constituents bemused at best, and leaving himself potentially vulnerable to defeat.

1 Crockett remembered that Alexander’s “vote on the tariff law of 1824 gave a mighty heap of dissatisfaction to his people. They therefore began to talk pretty strong of running me for Congress against him.” Crockett went on to say that his initial feeling was to decline, citing lack of preparation and knowledge as ostensible reasons, though a spotty or nonexistent résumé had never stopped him before. “I told the people that . . . it was a step above my knowledge, and I know’d nothing about Congress matters.”

He might have been slightly disingenuous here, for in 1824, some months before he officially offered himself for the candidacy, and perhaps while still serving in the state legislature, Crockett sent out a circular to the district that included the following appeal:

I am not one of those who have had the opportunities and benefits of wealth and education in my youth. I am thus far the maker of my own fortunes . . . If in the discharge of my duties as your representative, I have failed to exhibit the polished eloquence of men of superior education, I can yet flatter myself that I have notwithstanding, been enabled to procure the passage of some laws and regulations beneficial to the interests of my constituents.

2

Clearly Crockett plays on the emotions here, underscoring his humble origins, while at the same time jabbing barbs at the moneyed and educated. Throughout his political career he would face opponents with more money, connections, power, and influence, always assuming the role of the reluctant underdog. His ill-fated first attempt at Congress was no exception, and Crockett said that finally, at continued pressure from friends, “I was obliged to agree to run.” It was a mistake, for he wasn’t ready yet, and the result would offer schooling in the dirty machinations of national politics, games and power plays about which Crockett was untutored.

3First of all, Crockett didn’t have the financial means to run a successful campaign, which would require printing costs, travel expenses, and worst of all, more time away from farm and fields and hunting grounds. He felt that he was well liked in his local area, but the congressional district covered an impressive eighteen counties, and Crockett would need to venture far and wide to make himself known. It was simply beyond his current means.

His opponent, Adam Alexander, did not share Crockett’s indigence or lack of influence. He was close with Jackson, and with two other significant “Jackson supporters,” Felix Grundy and Judge John Overton. Crockett had already alienated Grundy in the previous legislative session when he voted in favor of Williams over Jackson for senate, and Crockett would quickly come to understand that such decisions came with consequences. In politics, allegiances mattered, and people tended to hold grudges.

A number of factors conspired to doom Crockett in that first attempt at Congress, though he would later blame it all on the price of cotton. It’s true that cotton prices ran miraculously high in 1825, up to $25 per hundredweight, nearly five times the average price, and it’s true that Alexander was quick to jump on this fact, taking credit for it in the two main papers, with which he had connections and influence while Crockett did not.

4 To complicate matters, John Overton began to have some fun at Crockett’s expense, partly in retaliation for Crockett’s vocal opposition two years earlier to moneyed planters and speculators, of which Overton was both. Writing under the nom de plume of “Aristides,” he took Crockett to task for attempting to change court days and to add an East Tennessee brigade to the militia of the Western District.

5 Overton made a convincing case against Crockett with sustained newspaper postings, an onslaught that lasted over three months and kept Crockett constantly on the defensive. In the end, with the peoples’ purses bursting from the high cotton prices, and Alexander promising that there would be equally high prices for everything else they manufactured and sold, Crockett’s entreaties fell on deaf ears. “I might as well have sung

salms over a dead horse, as to try to make the people believe otherwise; for they knowed their cotton had raised, sure enough, and if the colonel hadn’t done it, they didn’t know what had.”

He was unable to persuade the voters differently, and this, combined with his general political naïveté, cost him dearly. Though years later in his autobiography Crockett would remember incorrectly that he lost by “exactly

two votes,” the real tally difference that August was not two, but 267. Given his lack of preparation, Crockett’s showing was better than he let on; he had received 2,599 votes of the 5,465 total cast.

6 But he was not accustomed to losing, and the fact that he later fudged the poll figures suggests that he took defeat hard. In a move that would become a pattern, Crockett chose to pacify his hurt pride by heading back out into the canebrakes to hunt, out into open country where he conjured schemes for making easy profits to get ahead, always dreaming of ways to make his fortune.

One such enterprise involved some speculation of his own, for no sooner had Crockett returned home from his defeat than he made a trip of some twenty-five miles to Obion Lake, where he hired a small crew and put them to work building two large flatboats, which he intended to pile high with cut barrel staves and float to market in New Orleans. The plan seemed sound, if a bit ambitious for the self-described landlubber Crockett, and he felt confident enough to leave the construction of the craft to his men while he got down to the more serious and enjoyable business: “I worked on with my hands till the bears got fat, and then I turned out to hunting, to lay in a supply of meat.” It would be his most productive winter hunt ever, and he ended up supplying not only his family, but many other friends and relatives, with an abundance of meat, sustaining, and even augmenting, his backwoods legend. Crockett by this time had acquired an impressive pack of “eight large dogs, and as fierce as painters [panthers]; so that a bear stood no chance at all to get away from them.” Crockett took his dogs and hunted for a few weeks with a good friend, and when he’d filled the friend’s larders he spent some time helping his boys with the flatboats and the collection and cutting of barrel staves, but the work grew tedious and his mind wandered. “At length I couldn’t stand it any longer without a hunt,” he admitted. The hunt coursed through his veins, so he took one of his younger sons (either Robert Patton, nine, or William, sixteen), with or without Elizabeth’s complete blessing, and headed out for a long hunt. The hunt proved notable because during this winter, in an oft-told story, he killed a massive bear with nothing but a knife.

One day early in the winter hunt, Crockett came across a downtrodden fellow who he described as “the very picture of hard times.” The man bent over a rough field, hacking away with a heavy implement and trying to clear the ground of roots, stumps, and boulders in a process called “grubbing.” Crockett stopped to chat with him, and commiserating when the other informed him that it wasn’t even his field; he was grubbing for another man, the owner, to get money to buy meat for his family. Crockett struck a deal with the man: if he would go with Crockett and his son and help pack and salt the slain bears, Crockett would provide the man with more meat than he could earn in a month of this backbreaking grubbing. The man retired to his rustic cabin, conferred with his wife, then reappeared with her blessing, and off they went. They killed “four very large fat bears that day,” and in the course of only a week added seventeen more. Crockett relates that he quite happily gave the man “over a thousand weight of fine fat bear-meat,” pleasing both the man and his wife, and when he saw him again the next fall, he learned that the meat had lasted him out the entire year.

Crockett and his son later hooked up with a neighbor named McDaniel, who also needed a good supply of meat. They struck out to likely ground between Obion Lake and Reelfoot Lake, the brambly “harricane” country some of Crockett’s most coveted and productive, the strewn and tangled timber providing perfect cover for the animals. They followed ridges dense with cane, peering inside the hollows of black oaks in search of hiding bears, using Crockett’s wily techniques of finding treed bears by noting the differentiation of scratch marks on a tree bark. On the third day Crockett and McDaniel left the young boy in camp and headed deep into the cane, but found the going slow “on account of the cracks in the earth occasioned by the quakes.” The deep troughs and fissures forced them to go around in places, and soon they met a bear coming straight at them, and Crockett sent his dogs off and they howled in pursuit. Crockett remembered this bear well, noting that “I had seen the tracks of the bear they were after, and I knowed he was a screamer.” Crockett kept hotly after the bear, the foliage so tight in places that he was reduced to traveling his hands and knees: “The vines and briars was so thick that I would sometimes have to crawl like a varment to get through at all.”

In time he managed to scramble through, and he found that his dogs had treed the bear in an old dead stump, and shaking with fatigue Crockett just managed to shoulder his rifle and bring the bear down. With McDaniel’s help they butchered and salted the bear, “fleecing off the fat” as they skinned the animal and packed the prepared meat on horses. They rode when they could, but mostly they walked, and they reached the camp around sunset. Crockett called out and his son answered, and as they moved in the direction of camp, the dogs opened up again, baying into the sunset. Never one to forgo a fresh chase, Crockett handed his reins to McDaniel and trotted off after his hounds into the darkening skies.

The night fell fast under the canopy of cane and Crockett stumbled along, bashing his shins on fallen logs and falling into clefts in the earth left by the quakes. He forded a wide cold creek, then broke from the stream bank to scale a severe incline, clawing his way up the hillside. When he made the summit, he located his dogs and found they had treed the bear in the fork of a tall poplar. It was so dark that all he could see was the outline of a large lump in the fork of the tree, and aiming by guess-work, he fired. He missed, but the bear obliged by venturing out onto a limb where Crockett could see him better and he reloaded fast and fired again. He didn’t see the bear drop so he began a third reloading. Suddenly there was the bear, down on the ground with the dogs all about him in a snarl of teeth and claws. Crockett was too close for comfort, so he pulled out his big butcher knife as protection and waited while the roaring roll and tumble of flesh and fur went on and on, his one white dog showing as an occasional flash amid the brown and black of the bear and other dogs, the whirl of animals coming at times within a rifle length of Crockett.

Finally the dogs forced the bear into a large crevasse in the earth and Crockett could tell “the biting end of him by the hollering of my dogs.” He pushed his rifle into the crack, felt around, and when he thought he had it pressed against the bear’s body he fired, but he only wounded its leg, and the bear, injured and enraged, broke from the hollow and went another round with the dogs before they drove him back into the crevasse again. After spearing the bear with a long cut pole, Crockett determined to risk crawling in after him, hoping the bear would remain still long enough for him to “find the right place to give him a dig with my butcher.” He sent the dogs in first to keep the angry bear’s head occupied, and he snuck around behind, placing his hand bravely on the bear’s great rump, feeling for the shoulder. “I made a lounge with my knife, and fortunately stuck him right through the heart; at which he just sank down.”

Crockett quickly got out of the crack, and when his dogs backed out too, bloody and panting, he knew the bear was finished. It had been a tremendous fight, and now Crockett had the difficult task of getting the massive animal out of the hollow, which he managed with great effort, dragging the bear a few feet at a time until he had him up on the ground and could butcher him. Exhausted, Crockett slumped on the ground to sleep, but his fire was too feeble to warm him, and he was wet through from sweat and the river he’d crossed. Soon he was shivering and shaking, his teeth chattering, his core body temperature plunging dangerously low. He tried to find dry wood to burn but it was all green or wet, and he knew he was in trouble. He began leaping and hollering in the air, hurling himself “into all sorts of motions,” but hypothermia began to set in: “for my blood was now getting cold, and the chills coming all over me.” At last he was so spent that he could barely stand, and he understood that he absolutely must get warmer or else he would perish:

So I went to a tree about two feet through, and not a limb on it for thirty feet, and I would climb up it to the limbs, and then lock my arms together around it, and slide down to the bottom again. This would make the insides of my legs and arms feel mighty warm and good. I continued this till daylight in the morning, and how often I clomb up my tree and slid down I don’t know, but I reckon at least a hundred times.

7

His ingenuity having kept him alive, Crockett hung his bear and headed back to camp, where his boy and McDaniel were very happy to see him. They ate breakfast, and Crockett told them about the tough night he’d been through. Then he led them back to retrieve the big bear. McDaniel wanted to see the crack where Crockett had slain the bear with only his knife, and after he looked it over he came out shaking his head and exclaimed that he’d never have gone in there with a wounded bear, not “for all the bears in the woods.” McDaniel would certainly have told that story at taverns, and to visitors, time and time again.

They concluded this hunting trip by bagging a few more bears, then salting and loading all the meat on their five pack horses and heading home. McDaniel went home with meat enough for the year, and that fall and winter Crockett counted fifty-eight bears that he and his hunting partners had brought in. In spring, the bears out of hibernation, he went out again, and in just a month he bagged forty-seven more, boasting a historic count of 105 bears in less than seven months, a number that would be considered illegal and “game hoggery” by modern standards but was perfectly acceptable and plausible at the time. Though Crockett, like many hunters and in keeping with the tall-tale tradition, sometimes lapses into hyperbole, his legendary abilities as a hunter are confirmed by a host of his contemporaries.

8Sated emotionally with his best hunt ever, Crockett returned to his barrel-stave project in mid-January 1826. In his absence his hired hands had been productive, piling the two flatboats with some 30,000 staves, which Crockett figured would turn a healthy profit in New Orleans. The flatboats were large and unwieldy rectangular craft, fashioned of rough-hewn wood and finished with a central cabin where those off duty could sleep or eat out of the weather. They were basic, utilitarian boats often made for single trips, as they could be easily dismantled at the end of a run, their lumber sold along with whatever cargo they carried.

9 Men navigated the sluggish boats as well as they could, standing on top of the cabin, in the bow, and along the sides and rowing with long, sweeping strokes. Crockett had no nautical experience, but the lure of profit drove him even into the unknown, mysterious element of dangerous waters, and when the boats were completely loaded and tied down and some provisions stored, he and his crew boarded and pushed off into the Obion. Everything seemed to float smoothly until they converged with the great, churning Mississippi, at which point Crockett discovered that “all my hands were bad scared, and in fact I believe I was scared a little the worst of any; for I had never been down the river, and I soon discovered that my pilot was as ignorant of the business as myself.”

The river was bigger than any of them had imagined, the deep water dark and eerily powerful. Soon the boats yawed and spun uncontrollably, and Crockett lashed them together, hoping to steady them. This made the boats “next akin to impossible to do anything with, or guide them right in the river.” The awkward tandem drifted sideways in the river, and Crockett discovered to his dismay that they could not even intentionally land the boats, or even run them aground, though he tried to do so more than once. They were at the absolute mercy of the river.

Just before nightfall, some Ohio river boats passed and recommended, against Crockett’s wishes and instincts, that they float on through the night. All night long they made futile attempts to land, as people along the shore communities would run out with lanterns swinging, shouting directions that the inept boatmen were unable to follow. Eventually they came to a tight turn in the river called the Devil’s Elbow, which Crockett allowed was perfectly named: “If any place in the wide of creation has its own proper name, I thought it was this. Here we had about the hardest work that I ever was engaged in, in my life, to keep out of danger; and even then we were in it all the while.”

Finally Crockett threw his hands up in futility and quit trying to land, resigned to just float along, come what may. He went below into one of the cabins and rested, thinking and reminiscing. “I was sitting by the fire, thinking on what a hobble we had got into; and how much better bear-hunting was on hard land, than floating along on the water, when a fellow had to go ahead whether he was exactly willing to or not.”

Crockett’s boat rode behind, and about that time he heard men scurrying on the deck above, their voices crying out hysterically as they heaved and pulled, and then the boat slammed violently into the head of a “sawyer,” a bobbing sunken tree that impaled the boat. The current instantly sucked the first boat down, and feeling his own boat swamping, Crockett scrambled for the hatchway but water poured through in a thick cold current “as large as the hole would let it, and as strong as the weight of the river could force it.” The boat flipped over sideways, “steeper than a housetop,” and the main hatch offered no escape.

Crockett remembered another small hole in the side, which was now above him, and he clawed for that. It was too small to crawl through but he thrust his arms and face out and hollered for his life. Water had filled the cabin and now crept up almost to his head when some of the deck-hands heard him screaming and leapt to grab his arms.

I told them I was sinking, and to pull my arms off, or force me through, for now I know’d well enough it was neck or nothing, come out or sink. By a violent effort they jerked me through; but I was in a pretty pickle when I got through. My shirt was torn off, and I was literally skin’d like a rabbit.

As it turned out, Crockett was well pleased to get out any way he could, because the moment they pulled him out, the craft went entirely under. They all managed to jump to a foundered mass of logs. It was the last he would see of his boats or his staves. He and his crew remained on the logjam through the night, shivering in what little clothing they had on. All else, including Crockett’s would-be fortune, had been lost. They were marooned at a place called “Paddy’s Hen and Chickens,” just above, and within sight of, the bustling city of Memphis. Crockett later remembered that deep in that night, shaking with cold and now penniless and destitute, he did not feel sorry for himself: no anguish, despair, or self-pity. Rather, a curious kind of calm, a surreal contentedness, washed over him as he sat stranded on the island: “I felt happier and better off than I ever had in my life before, for I had just made such a marvelous escape, that I forgot almost every thing else in that, and so I felt prime.”

Early the next morning a passing boat recognized their distress and sent a skiff for them, where they found the men tired, wet, cold, and hungry, the cantankerous and revitalized David Crockett sitting buck naked on his shredded shirt. News of the men had traveled downstream, and their sinking stave boats were spotted plummeting headlong down the river, and when the rescue skiff arrived at the docks in Memphis, curious onlookers were on hand to see what all the hubbub was about. Among the throng was a man named Marcus B. Winchester, a prominent Memphis businessman who owned department stores and would later become post-master of Memphis during the Jackson administration. Winchester kindly took the distressed travelers to one of his stores, where he clothed the men, and then he offered to host them in his home, where his wife gave them much needed food and drink.

10Warmed, fed, clothed, and happy to be alive, Crockett and his men hit the town, partying all night long, sharing horn after horn and telling tales of their travels and near-death adventures, Crockett the most vociferous and animated of the group, and certainly the best storyteller. Small crowds gathered at each tavern they visited, and Crockett held forth, cheers and laughter going round with each unbelievable tale. Marcus Winchester took keen note of the attention Crockett received, impressed with the way people gravitated toward him and responded to him.

Winchester was so taken with Crockett that the next day he took him and his crew again to his store and outfitted them with shoes, hats, and enough clothes for their return upriver, and he even decided to give Crockett some money, urging him to run again for Congress and promising to back him if he did so. Crockett sent most of his men home, and took just one comrade downstream by steamer to Natchez, to see if by some miracle they might recover their rogue flatboat, which had actually been spotted some fifty miles downstream. Crockett noted that “an attempt had been made to land her, but without success, as she was as hard-headed as ever.” She would remain so, and though Crockett made a strong effort, the boat was never recovered.

11As was often the case with Crockett, once disaster was averted, he emerged stronger and more vital than before. In this case, he had become something of the darling of Memphis, with stories circulating about the larger-than-life bear hunter who washed up naked and bleeding on the shore. Major Winchester observed this growing notoriety and reiterated that he would back Crockett in the upcoming congressional election of 1827, providing him with campaign money as needed to make a second run against Alexander. So, though he had lost his entire entrepreneurial enterprise, he finally returned to his Elizabeth and his family in good old Gibson County, sometime in the early part of the summer of 1827, with quite a story to tell. Instead of having his tail between his legs, he arrived spry and sassy, flush with some hard grit in his pocket and a new benefactor down in Memphis, a thriving and politically influential river town in the huge Ninth Congressional District.

12Elizabeth and the young Crocketts would have been happy to see the truant patriarch, but the reunion was tempered with the news that he needed to get right out on the campaign trail for the upcoming elections, to be held in August. If Crockett knew that it would be a difficult task to unseat an incumbent as strong and savvy as Alexander, he did not let that challenge dampen his spirits or his conviction, and in fact he appears to have been bolstered by a new positive attitude after surviving yet another close call, this time at the providence of the mighty Mississippi River. Not only did Winchester agree to provide campaign support and a loan to Crockett, he also made frequent business trips down in Crockett’s region, and the two would meet and socialize. Winchester promised to talk Crockett up to his influential friends, a fact about which Crockett felt no compunction; it was simply the way politics worked.

My friend also had a good deal of business about over the district at the different courts; and if he now and then slip’d in a good word for me, it is nobody’s business. We frequently met at different places, and, as he thought I needed, he would occasionally hand me a little more cash; so I was able to buy a little of ‘the creature,’ to put my friends in a good humour, as well as the other gentlemen, for they all treat in that country; not to get elected, of course—for that would be against the law; but just, as I before said, to make themselves and their friends feel their keeping a little.

13

Crockett benefited from other social factors as well. The price of cotton, which he used as an excuse in his loss to Alexander two years before, was now back down to earth at $6 per hundredweight, so Crockett cleverly keyed on this fact, plus the very real situation of occupant dispossession in the Western District as a result of extensions to the North Carolina warrants. Crockett harnessed his campaign simply: he would run “against the tariff and for a congressional solution to the land problem.”

14 To help things even more, two other candidates entered the skirmish: John Cooke and General William Arnold, and their presence could potentially take some of the vote away from Adam Alexander, especially the addition of Arnold from Jackson, who took his open animosity against the incumbent to the forum of public debate, undermining some of Alexander’s credibility.

15Crockett had three recent campaign races under his belt, and he had learned from each one, so that he came to the summer of 1827 as a seasoned campaigner with a firm command of his public persona. His strategy this time around was simple: he would give the voters what they wanted to hear, and he would most importantly give them what they wanted to see—a real-life backwoodsman who was a mouthpiece for them, who shared their dreams and aspirations but also their frustrations and concerns, a thighslappingly funny storyteller who lived “out amongst ’em.”

His first challenge was to deal with the loud-mouthed and long-winded John Cooke, who launched an aggressive personal attack on David Crockett’s character traveling all about the district and publicly reviling Crockett as an adulterer and a drunk, and generally trying to undermine him as indecent.

16 Crockett responded by fighting fire with fire (in much the same way politicians use mud-slinging commercials today), casting equal and worse aspersions against Cooke, most of them utter fabrications, but who cared? He was having a good time trading lies with Cooke, stooping to his level and then crawling even lower. Cooke decided to ensnare Crockett in his egregious lies by attending a political rally with his own witnesses in support, and, after one of Crockett’s lengthy tirades, coming forward and exposing him publicly as a liar. Thus caught in the act and exposed by his witnesses, Cooke reasoned, the disgraced Crockett would wither away and perhaps even withdraw from the race.

The plan backfired in Cooke’s face like a ten-pound cannon. At the event, Crockett rose to speak with unusual bluster, laying on outrageous falsehoods even thicker than usual. Now an expert at timing, Crockett let the air grow still and pretended to be finished, feigning a move to take his seat but then pausing, clearing his throat, and stepping up again. He wished to add one last comment. At length he informed the gathering that his opponent was among them, and planned to expose him as a liar; he’d even brought his own witnesses with him for the purpose of doing so. Crockett grinned his patented wildcat smile and pointed out that the witnesses were entirely unnecessary—they could all be witnesses, for he was quite happy to admit that he’d been telling lies. What choice did he have? His opponent had started the fight by slurring him with slander and outright lies, and so, to keep things fair and even, he had responded with lies. In fact, truth be told, they were both liars!

17An informer had obviously tipped Crockett off, and the result was devastating for Cooke, who never even had an opportunity to respond, so uproarious was the laughter from the crowd. Crockett was the hero of the day, and Cooke could only burn with indignation as the crowd rallied around their man, David Crockett. Cooke soon withdrew his name from the running, claiming that he was morally superior and could not in good conscience serve a constituency that would cheer an acknowledged liar. Cooke felt the embarrassment for a long time, and could see that he was outgunned, for “two years later he rejected an opportunity to face Crockett in a rematch.”

18 Using his trademark humor, and embracing his role as a trickster, Crockett had single-handedly dispatched one of his opponents by simply being funny and, ultimately, truthful.

In the meantime, Alexander and Arnold locked horns, and in doing so, made a fatal error: they completely overlooked Crockett as a serious threat. Alexander remembered his decisive victory of two years earlier and seemed little threatened or concerned by Crockett this time around, instead focusing his attentions on Arnold, who by necessity responded in kind. Crockett put it this way: “My two competitors seemed some little afraid of the influence of each other, but not to think me in their way at all. They, therefore, were generally working against each other, while I was going ahead for myself, and mixing among the people in the best way I could.”

His mixing proved to be just right, and around the region Crockett was now entrenching himself as the peoples’ candidate. He was a self-made man, and he began to comprehend what being popular felt like. His talk was so straight and genuine that people simply couldn’t help but like him. He had developed a style, complete with a country accent, mannerisms, and scathingly funny comic timing, and most remarkable of all, it was really him. He made certain to season his short speeches with regional jargon, understanding the efficacy of homilies like “A short horse is soon curried,” knowing that the common folk would appreciate the slang. He may have been exaggerating some, but he wasn’t faking it. What Crockett gave them in the congressional race of 1827 was pure and authentic Crockett.

For years after the election Crockett liked to tell the story of how all three candidates convened once at a stump meeting in the eastern counties, and how, as usual, Arnold and Alexander had completely ignored Crockett, treating him as if he did not even exist. On this occasion Crockett went first, and spoke very briefly and simply, knowing from experience that the other two would be remembered for their long, protracted, and boring speeches, and he for his good humor and cunning wit. Crockett listened attentively as they railed away at each other, first Alexander, then Arnold:

The general took much pains to reply to Alexander, but didn’t so much as let on that there was any such candidate as myself at all. He had been speaking for a considerable time, when a large flock of guinea-fowls came very near to where he was, and set up the most unmerciful chattering that ever was heard, for they are a noisy little brute any way. They so confused the general, that he made a stop, and requested that they might be driven away. I let him finish his speech, and then walking up to him, said aloud, ‘Well, colonel, you are the first man I ever saw that understood the language of fowls.’ I told him that he had not had the politeness to name me in his speech, and that when my little friends, the guinea-fowls, had come up and began to holler ‘Crockett, Crockett, Crockett,’ he had been ungenerous enough to stop, and drive them all away. This raised a universal shout among the people for me, and the general seemed pretty bad plagued.

19

David Crockett’s eccentricities were getting him noticed, and crowds of people came just to get a peek at him, and if they were lucky, to hear some of his well-wrought anecdotes. At the same time, Crockett had learned just enough in the legislature to understand that political allegiances mattered, though he never learned that lesson well enough to make it stick—when it came down to a vote, his conscience and his principles always triumphed over any political alliances. Still, despite his vote against Jackson in 1825 and his suspicion of him as privileged rather than one of his own kind, Crockett was outwardly and honestly a backer of Jackson at that time: “I can say, on my conscience, that I was, without disguise, the friend and supporter of General Jackson, upon his principles as he laid them down, and, as ‘I understood them.’ ” Of course, the provision between Crockett’s quotation marks became important later on, foreshadowing a moment when Crockett would make the case that even Jackson himself no longer ascribed to his own principles, but for the moment, Crockett supported Jackson’s upcoming run for the presidency in 1828.

By election time in the late summer of 1827, Crockett had done all he could in an attempt to unseat an incumbent, one who had beaten him the last time around. His face and voice and outlandish storytelling had been spread all around the district; Marcus Winchester’s endorsement, introductions to influential circles, and fiscal backing had ensured that. The rest was pure Crockett. When the polling numbers came in, even Crockett had to be a bit surprised. Before the election, he had admitted that he was a long shot, as unseating an incumbent like Alexander was difficult in the best of circumstances, and in Arnold he faced a very clever major general in the militia, and a lawyer as well, which Crockett viewed as nearly insurmountable: “I had war work, as well as law trick, to stand up under. Taking both together, they make a pretty considerable of a load for any one man to carry.” But the resilient Crockett managed to shoulder that load, and more, for the final count shocked everyone and sent tremors rumbling all the way past Memphis to Washington City. The turnout had been excellent, and 2,417 had voted for the barrister Arnold. Alexander received an impressive 3,647, nearly a thousand more than the number that got him elected in 1825. But it was the quirky and enigmatic David Crockett who carried the day, his remarkable 5,868 votes representing a solid whipping laid on his opponents.

20 His election signaled a new era in American politics, one that gave hope to the common fellow. A man like Crockett spoke his piece and then went ahead—no posturing, no empty or blanket campaign promises, no obfuscation and misdirection by belaboring complicated and dull issues. Here was an original straight shooter, a rustic and woodsy neighbor you’d be comfortable with trading yarns at the local tavern, and one in whom a new generation of voters could see themselves.

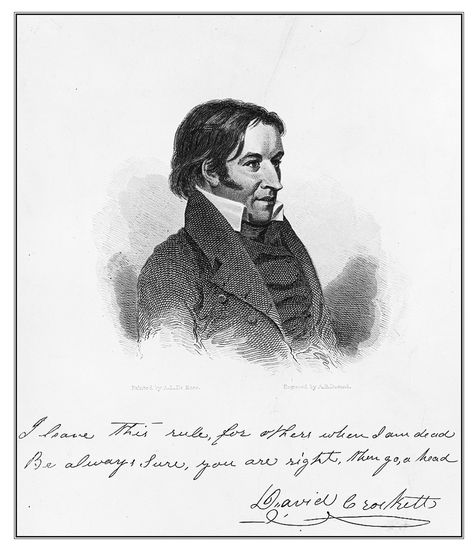

The last portrait of Congressman Crockett, dressed as a gentleman, as he would have appeared during his days in Washington. (David Crockett. Portrait by Asher Brown Durand, engraving on paper, copy after Anthony Lewis de Rose, print circa 1835. Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC.)

The bear hunter from the cane had wrestled and yarned his way into the tricky arena of national politics, and he was heading to Washington City. David Crockett was ready for the challenge, and if it turned out that he wasn’t quite qualified for the job, he was a quick study and he would learn as he went. In truth, he really had no idea precisely what he had gotten himself into. What remained even less clear was whether Washington City was ready for Congressman David Crockett of Tennessee.