TEN

Crockett’s Declaration of Independence

DESPITE FEELING PHYSICALLY BETTER than he had in recent memory, Crockett arrived home psychologically battered. Learning to be thick-skinned was one thing, but not knowing friends from enemies was quite another, and by now Crockett had begun to look over his shoulder. To complicate matters, he faced a short campaign season ahead, and probable ire from Elizabeth at home, having incurred another significant debt, this one for $700, in order to square up his bills at the boarding house and finance his journey back to Tennessee.

1 Crockett had developed a pattern of borrowing and spending more than he had, then spending months or years to work off the debt. As a lad he had witnessed the same cycle in his father, and try as he might, he could not seem to shake it. That burden of debt load prefigured the American Way for the twentieth-century American middle class, but all Crockett knew at the time was that he must remain solvent if he could, and that meant some brief “howdies” at home, then off to circulate in his district and see what kind of damage had been sustained by the papers and his inability to push the land bill through.

Crockett spent less than two weeks at home attending matters of the farm, and likely having words with Elizabeth about his perpetual absence, before striking out on a three-week sojourn through his own and adjacent districts that was part campaigning and part damage control. In addition to the embarrassing accounts relating his alleged behavior at the presidential dinner, a March 7 lampoon in the

Jackson Gazette derided his campaign techniques as unethical, citing his drunkenness and penchant to buy votes with booze, despite his having sworn off the stuff in the last session. The cartoon ran an image of Crockett exclaiming that he could always find willing constituents “who will sell both body and soul for good liquor. Let alone their votes.”

2But Crockett was renewed physically, perhaps the result of his temperate lifestyle, and he hit the hoistings hard, making important political visits along the trail. It appeared that his old nemesis Adam Alexander would also run for Congress again, and this fact pleased rather than worried Crockett. Confident that he could thrash Alexander once again, he went so far as to boast that he would outstrip him by 5,000 votes.

3 He moved through the districts, acting as the independent he had become, relying on his tried and trusted antics. In Memphis he made a stump speech from the deck of a flatboat very much like the one that had marooned him there, naked, back in 1826, an episode that had been elevated into lore around the city.

4 To adoring crowds he retold the barrel-stave disaster, exaggerating the details for effect, and once he knew he had the audience under his thumb he made the broad boast that he could “jump higher into the bay, make a bigger splash, and wet himself less than any other man in the crowd.”

5 To his great surprise a monolith of a man took the bet, and Crockett begged off, paying up to the great delight of everyone, and the politics quickly turned to partying, more storytelling, and tavern camaraderie.

But while Crockett was busy winning votes in the only way he knew how, his tactics fueled the fire of the opposition and allowed them to continue their onslaught of slurs. Though it was still unclear to Crockett what the sources of the accusations were, the press and its readership devoured them. Broadsheets, newspaper articles, and rumors circulated citing Crockett’s gaming, debauchery, even adultery.

6 Crockett fended off some claims, ignoring most, while narrowing his eyes to discover their source. Alexander himself was certainly in the mix as his only real opponent, but Crockett had to wonder if larger forces were at work, perhaps those inside the Jackson camp, or allies of Polk.

In Nashville Crockett visited with his friend and colleague Sam Houston, who was in the throes of personal and professional upheaval: he had just resigned his gubernatorial post and separated from his wife, Eliza Allen. The entire state of Tennessee was in shock over the news, and during their meeting Crockett asked Houston what his plans were now. Houston remembered fondly his years living among the Cherokee, and he considered the Indians his brothers. He painfully recalled how, in his role as an Indian agent and infantry lieutenant, he had helped drive his own family of the Cherokee nation, the Hiwassee, into exile in the Arkansas Territory. Houston told Crockett that he intended to go once again to be among his people, this time in Arkansas.

7 Although neither would have known it at the time, the independent and maverick ideals of the two men would meet again some years later, becoming immortalized—in quite different ways—on the rugged Texas plains.

Crockett’s skills as an orator and campaigner, coupled with his familiarity with the people and region, made him a formidable opponent in 1829. But his fierce, even obstinate independence remained ill suited to party politics. Crockett took everything personally, and he often had difficulty seeing the larger scheme of things, the apparatuses of politics beyond the hand-to-hand combat of a stump campaign. As a result, he failed to understand that the feisty independence which made him popular as a candidate also ostracized him and made him potentially dangerous in the eyes of the Jacksonian Democrats as well as the Whigs, the anti-Jackson group formed within the Democrats. The upshot was that Crockett was in the process of becoming a man without a party. At the time, “Jackson forces were trying their best to make Crockett an object lesson—the first in American politics—of the price to be paid for the sin of breaking ranks.”

8 They viewed such independence as treason. The problem was, the naïve good ol’ boy never saw it coming. He was too busy hamming it up on the stump trying to get reelected.

His efforts that spring and summer paid off, and by close of the election in August, Crockett had indeed routed Alexander. Though he failed to equal his brash prediction of crushing him by more than 5,000 votes, he did manage the significant margin of 6,773 to Alexander’s 3,641, receiving 64 percent of the vote.

9 Despite all the mudslinging, Crockett had emerged victorious once again, confirming his belief, if not in politics proper, in himself and his ability to convince people that he was right, that he was a man with their best interests at heart. He had also learned to refine his image somewhat—at least in part to keep the hawkeyed Elizabeth appeased—and also as a role for the benefit of his constituents—playing on his newfound religious conviction, his at least temporary sobriety, and his balance of earthy backwoodsman and sophisticated gentleman. That was a difficult balance, for he knew that he needed to speak the language of the folk so as not to appear as though he was succumbing to the lure of the city. At the same time, he understood that he must possess some of the refinements of gentlemanly culture, lest he appear the boor depicted by some of his foes.

10 It would be a duality he would attempt to perfect during his entire run at politics, a kind of “image schizophrenia” that would eventually tear away at him. But for the moment, he considered himself the darling of Western Tennessee, and to a large extent he was. In fact, his name and aura were beginning to attract attention beyond the small sphere of his home state. His persona was taking on a life of its own. And at the same time, he seemed to represent the sharecropper’s yearnings for independence, their humble desire for opportunity, that hopeful if tenuous vision shared by thousands of settlers migrating west and trying to make a go of it on the land.

11So it was that David Crockett returned to Washington City when the Twenty-First Congress convened on December 7, 1829, and immediately took up his obsession, the land bill. In a bold move, Crockett set out to extricate the issue from the Committee on Public Lands, headed by Polk, and position it instead within a special or select committee, which he himself would chair. He received a bit of impetus from the Henry Clay faction, and perhaps to his surprise, his motion was granted over Polk’s vehement protestations. Crockett’s desire was confirmed in a vote of 92 to 65, “approving his amendment and rejecting Polk’s.”

12 The tide appeared to be shifting Crockett’s direction, if only temporarily, and it looked to him like he might finally get some action on his coveted bill. He now had a stronghold on the committee, and he believed naïvely that things boded well. For weeks Crockett’s committee wrangled over the wording of the bill, and at last Crockett felt like the iron must be hot enough to strike, so on December 31 he moved that the House reconsider the Tennessee Land Bill, but to his continued chagrin his motion was denied.

13After weeks of further debate, much of it vitriolic, Crockett proposed a revised version of the bill in early January, but it failed once again. An optimist to the very end, Crockett must have begun to sense some futility, as well as understand that something larger than the merits of the bill were at stake and being debated here. It had become personal, and Crockett was being singled out and alienated for his break with Jackson.

14 Against his nature and his political tendencies, Crockett and his committee finally came forth with a revised bill, one that made some concessions. The bill’s central tenet was to cede to Tennessee 444,000 acres in the Western District, equivalent to the sum of the 640 acres in each of the state’s townships set aside for “common schools.”

15 The state would be able to sell the land and apply the profits toward education, but it would also give squatters the option of buying, at twelve and a half cents per acre, up to 200 acres that they either intended to improve or had already improved.

Crockett could only shake his head, outwardly hopeful at the compromise he had made. He later admitted that “this is the best that I could do for my constituents.”

16 Delegates of North Carolina balked at the bill’s terms, claiming that their warrants were being overlooked, and on May 3 it was defeated 90 to 69. Livid, Crockett quickly moved for the bill, in further revised form, to be reconsidered, though by now he appeared to be begging. He was floundering, with only Cave Johnson remaining an ally among his own Tennessee delegation, and his motion was tabled until the following autumn session. It was a bitter defeat for Crockett, and a confusing one, especially when things had looked so promising just weeks before. Even a man as politically obstinate as David Crockett must have suspected collusion. He was proud enough to interpret the failure of his bill as due not to his own shortcomings, but to more widespread and venal operations that were beyond his abilities to counter.

WITH HIS MEASURE TABLED until the following session, the fall/winter of 1830-1831, Crockett’s frustration led him into a pattern of monkey-wrenching that alienated him even further from his peers. He vehemently opposed the Military Academy at West Point, his feelings toward officers and privilege developed back in the Creek War when his own reconnaissance was ignored, but that of an officer’s was listened to attentively and then acted upon by his commander. Crockett believed that West Point was an institution reserved for the sons of the nobility and the wealthy, and that only graduates of the academy were granted commissions as officers, so that it became a self-perpetuating mechanism where once again the poor were shortchanged.

17 Crockett went so far as to propose the abolishment of the entire academy, adding in a qualification that sounded insulting, that “gentlemen were not up to the task of commanding soldiers” because they were frail and “too delicate, and could not rough it in the army because they were too differently raised.”

18 His motion struck his typical contrary chord, and it was summarily tabled and eventually died a quiet death.

Having lived his entire life in far-flung outposts many miles from civic centers or even modest-sized towns, Crockett knew the importance of viable roadways and navigable rivers and canal systems to encourage transportation and commerce. From his brief time in the East, Crockett could see the benefits brought by “internal improvements” such as good roads, workable harbors, and an organized infrastructure. Especially in his region, navigable rivers were paramount for transportation and for the sale and trade of personal goods.

Additionally, Crockett had long believed that the pioneers, who were the nation’s brave and underappreciated scouts, forging a life out of a dangerous wilderness, deserved at least some of the benefits enjoyed by inhabitants of the more established and developed East, since pioneers were the ones literally grubbing the way for western expansion. Crockett favored a bill for a national road extending from the famous port city of New Orleans all the way to Buffalo. But in a regionally motivated provision, Crockett went so far as to propose, for the good of the people in his area, that the road section originating in Washington should end in Memphis. He suspected that once again, the people of his district were being bypassed. “I cannot consent to ‘go the whole hog,’ ” he said, “but I will go as far as Memphis.”

19 He also reasonably argued that winter frosts and drifts rendered roads impassable, whereas rivers tended to be navigable year round. And he posed an interesting observation rife with foreshadowing, asking anyone to explain to him the usefulness

of a road which will run parallel with the Mississippi for five or six hundred miles. Will any man say that the road would be preferred to the river? And if the road should so terminate [that is, at Memphis], it would be on the direct route from this city to the province of Texas, which I hope will one day belong to the United States, and that at no great distance of time.

20

His amendment failed, and when the original bill surfaced again for a vote, Crockett grudgingly voted for the entire route, since it was once again the best he could do for his constituents. Crockett’s side lost badly, and the grim pattern of his ineffectuality persisted.

And something else was afoot. In April, Jackson had vetoed the Kentucky Maysville Road Bill, taking a firm position against internal improvements, and, unquestionably, in a political maneuver to spite Henry Clay, whose own position on such improvements mirrored Crockett’s for the most part.

21 Jackson himself, in a move that catered to Southern and Eastern Jacksonians, argued that local projects ought not be funded with federal monies. During the early part of Jackson’s first term, one of his primary concerns was paying down the national debt, and he viewed internal improvements as unnecessary expenditures counter to his aims. That was his official, public position. But behind the scenes, his veto was intended to undermine the Clay-Adams allegiance; at the same time, the move illustrated to Crockett that Jackson was a political opportunist, an equivocator, a leader who would flip-flop on an earlier position (prior to his election Jackson had supported improvements as long as they were for defense)

22 if it was personally and politically advantageous, even at the expense of the good of the nation. At least that’s how Crockett perceived the situation. And though up until this point Crockett had remained a supporter of Jackson’s administration and its central goals and platforms, now a serious rift began to form, one which would ultimately define Crockett as a rogue individualist and leave him politically isolated, a lone flag flapping helplessly in the wind.

The impending debates over the controversial Indian Removal Bill would hammer a wedge into that rift, splitting it violently into splintered cordwood.

ANDREW JACKSON HAD MADE NO SECRET about his position on Indians. His desire to subjugate them dated back to before his military victories in the Creek War, a position he voiced during the Jefferson administration when he resoundingly declared that if the Cherokee could not be civilized, “we shall be obliged to drive them, with the beasts of the forests into [the] Stony [Rocky] mountains.”

23 Now, having waited long enough and finally in a position of enough power to realize his desires, Jackson seized his opportunity for action. On February 22, 1830, Senator Hugh Lawson White of Tennessee, a man whom Jackson had earlier considered for secretary of war and who currently chaired the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, put forth a bill that would come to be known as Jackson’s Indian Removal Act, and which set off a nationwide controversy.

24Between late February and mid-May rancorous debate raged through the House. Many members, Crockett included, opposed the unbridled authorization of a $500,000 to carry out the relocation of remaining peaceful tribes to lands west of the Mississippi. In the first place, the sum was drastically insufficient to perpetrate such a scheme; relocation would ultimately require millions of dollars. Furthermore, the money would be allocated devoid of congressional accountability.

25 Opponents of the bill also contended that Jackson himself was meddling dangerously close in the due processes of legislature, intruding in the proceedings “without the slightest consultation with either House of Congress, without any opportunity for counsel or concern, discussion or deliberation, on the part of the coordinate branches of the Government, to dispatch the whole subject in a tone and style of decisive construction of our obligations and of Indian rights.”

26 Indian rights—now that was a novel concept. Senator Theodore Frelinghuysen spearheaded the opposition, objecting not only to Old Hickory’s heavy-handed intrusions, but also on basic principles: the government had broken a string of treaties with these people, yet continued to marginalize them, herding them south and west while devouring their land by forcing them to sign it over. Senator Frelinghuysen rightly noted the hypocrisy of calling them “brothers” while simultaneously stealing their sacred homelands.

27Jackson’s cleverly worded position on the issue had couched the “removal” in a positive, hopeful way, one bent not on destroying these remaining, generally peaceful tribes of Choctaw, Creek, and Cherokee, but rather designed to save them and their culture from complete assimilation. He noted the fate that had befallen the Eastern tribes, including the Mohegans, the Delawares, the Narragansetts, and warned that extinction awaited the Southern tribes if they were not voluntarily removed to

an ample area west of the Mississippi, outside the limits of any state or territory now formed, to be guaranteed to the Indian tribes, each tribe having distinct control over the portion of land assigned to it. There they can be Indians, not cultural white men; there they can enjoy their own governments subject to no interference from the United States except when necessary to preserve peace on the frontier and between the several existing tribes; there they can learn the ‘arts of civilization’ so that the race will be perpetuated and serve as a reminder of the ‘humanity and justice of this Government.’

28

Crockett and many others could see through the wording to the reality for the tribes in question. And Crockett himself had been shepherded from place to place long enough to understand what such forced migration felt like. It was true that his grandparents had been slain by the Creeks, and it was true that he had fought against the Indians in the Creek War, sent on special missions to “kill up Indians,” but David Crockett possessed a basic, central morality that told him this bill was unfair and unethical. He empathized with the Indians because in many ways he was exactly like them. At his core, all he really wanted was a modest piece of ground he could call his own, some likely and productive cane where he could hunt when he wanted, and the freedom to move about unencumbered by undue governmental regulation and jurisdiction. Additionally, Indians had saved his life more than once, picking him up and carrying him to the safety of an Alabama farmhouse as he lay dying from malarial fever, and aiding him and his starving men as they staggered through Florida. No, Crockett believed that this was an unjust measure—bad politics and bad for the country—and it would not stand. The Indian Removal Bill would be Crockett’s public break with Jackson.

When the bill finally came to a vote in late May, it passed by the excruciatingly slight margin of 102 to 97, falling along strict party lines and creating plenty of tension vis-à-vis alliances and coalitions, especially with the specter of election ramifications looming in the next cycle. Crockett antagonist Pryor Lea referred to the debate and vote on the bill as “one of the severest struggles that I have ever witnessed in Congress.”

29 Crockett himself, as he would to the very end of his days, stuck to his principles:

I opposed it from the purest motives in the world. Several of my colleagues got around me, and told me how well they loved me, and that I was ruining my self. They said it was a favorite measure of the president, and I ought to go for it. I told them I believed it was a wicked, unjust measure, and that I should go against it, let the cost to myself be what it might. That I was willing to go with General Jackson in everything that I believed was right; but, further than this, I wouldn’t go for him, or any man in the whole creation; I would sooner be honestly and politically d-nd, than hypocritically immortalized.

30

It was a bold and noble act. With the verbal stroke of a “nay,” Crockett had conspicuously cast the only Tennessee vote against the Indian Removal Bill, effectively hanging himself politically. After the contentious passage, Jackson wasted no time, signing the monumental bill on May 28, 1830. It was a deeply dividing event in the history of the United States, one that made legal the efficient and expeditious expulsion of entire Southern Indian peoples from their ancestral homelands.

31 The victory for Jackson propelled into motion a series of events that would culminate in the tragic Trail of Tears.

Crockett would later reflect on the proceedings, steadfast in his belief that he had done right: “I voted against the Indian bill, and my conscience yet tells me that I gave a good and honest vote, and one that I believe will not make me ashamed in the day of judgment.”

32Perhaps not, but before long he would have plenty of people, including his confused and angered constituents, to answer to. He had publicly snubbed the will of the executive leader Andrew Jackson, and the decision would go neither unnoticed nor unpunished.

Within the next month Crockett would attempt to assuage the fallout from his singular dissention within his state, penning a speech in which he attempted to simultaneously clarify his position and placate the voters. He acknowledged openly that it was an unpopular position to take, and that it would be difficult for him to find a person within 500 miles who agreed with his decision, yet he stuck by his vote to the end. In the speech, published in the

Jackson Gazette on June 19, less than a month after the vote, he implored his electors to understand that “If he should be the only member of that House who voted against the bill, and the only man in the United States who disapproved it, he would still vote against it; and it would be a matter of rejoicing to him till the day he died, that he had given the vote.”

33 He eloquently added that he could not bear to see “the poor remnants of a once powerful people” driven from their land and homes against their desires. He honestly told the people that “If he did not represent the constituents as they wished, the error would be in his head and not his heart.”

34 The editors of the

Gazette, while willing to publish Crockett’s speech, vehemently disagreed with him, and printed a note saying they “regretted” his stance. The headstrong Crockett never regretted his stance, unpopular as it was.

Ironically, while Crockett drifted into turbulent political waters, his general popularity blossomed. His name, his peculiar sayings and idiom, and stories about his character, even about meetings with him, were circulating from Washington City outward across the growing nation. While his brash and unwavering independence ostracized him from the powerful Jackson forces, it was becoming his notable trademark, establishing him as an “eccentric” and “original character.”

35 He was becoming more than a curiosity—he was on the verge of achieving celebrity at home and even abroad. Alexis de Tocqueville, a young French civil servant and aristocrat visiting America in 1831, wrote about Crockett in his work

Journey to America. Tocqueville learned of Crockett from others, and became fascinated by his unlikely ascension from the canebrakes to one of the greatest political bodies in the world. He marveled that a common man could rise to the distinguished halls of power in America. But more important, his assessment of Crockett’s character contributed to Crockett’s growing celebrity.

36 Crockett was the living, breathing embodiment of a

type, a Western character writ large, one that audiences and individuals yearned to glimpse more of.

37 He relished the interest, even if later, feigning modesty, he claimed that he could not understand it.

Strained relations with Elizabeth made recesses awkward, and Crockett spent as little time as he could at home, instead focusing on nurturing what positive associations he still had in Washington and around his region—such as his Adams-Clay connections, and others on the routes to and from the capitol and his home. By late summer, Crockett’s break with the Jacksonians was widely known. The Jacksonians themselves noticed his movements and the fact that he spent more and more time with known anti-Jackson types, including “Henry McClung, a friend of Houston’s and himself an outspoken Adams-Clay man.”

38 Crockett also fostered camaraderie with Matthew St. Claire Clark, whom he’d met during his first term and who was rumored to be an Adams-Clay crony. Crockett’s defection would have consequences, as he would come to understand in a few short months.

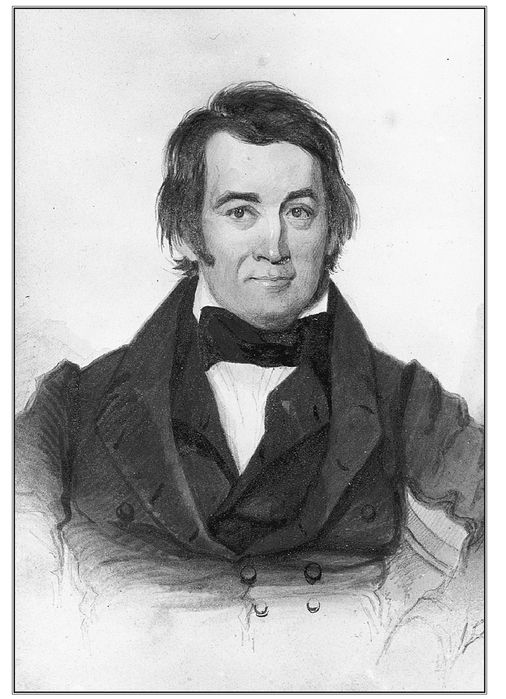

This portrait highlights Crockett’s high cheekbones, which he described as “Red Rosy Cheeks that I have carried so many years.” (David Crockett. Watercolor drawing by James Hamilton Shegogue, 1831. Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC. Gift of Algernon Sidney Holderness.)

Crockett finally returned to Washington in December a week late for the Twenty-First Congress, immediately scrambling to salvage something of the land bill if he could, understanding intuitively that failure to push it through would seriously threaten his chances at reelection. On three occasions he tried to get the bill reconsidered, failing each time, though the vote was painfully close. Frustrated, Crockett was suspicious of the apparatus that was keeping the land bill tabled, and he now took it personally. He openly argued with other members of his delegation and made thinly veiled references to Jackson’s dictatorial tendencies. On January 31, he created a brouhaha over the formation of a committee to review a petition of three Cherokee Indians claiming 640 acres of land apiece. Crockett believed the petition should be dealt with by the Committee of Claims rather than by Polk’s Committee on Public Lands. Crockett argued reasonably and compassionately that though the Indians had brought suit to reclaim land confiscated from them, they were too indigent to obtain proper legal assistance in the matter, and effective counsel from the state of Tennessee had been denied them.

39 His points were well taken, and after vigorous discussion the petition did find its way to the Committee of Claims, a token victory for Crockett but one that would have been noticed by Jackson and his forces, who had earlier repealed part of the 1789 Judiciary Act keeping the court from ruling on the issue.

40 Crockett was once again at direct and defiant odds with Jackson on questions involving Indians, and he felt that Jackson’s interference outstripped the bounds of his office’s duties and power.

Crockett fumed for the remainder of the session, losing a fight to gain appropriation for improved navigation on the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, another internal improvement issue, and now his choleric temper took hold of him. He could no longer contain his feelings about Jackson the man, whom he increasingly believed to be a hypocrite, an autocrat, and a powermonger. He lashed out at Jackson personally, accusing him of betraying the very principles he had espoused in getting elected. “When he quitted those principles, I quit him. I am yet a Jackson man in principles,” Crockett railed, “but not in name. I shall insist upon it that I am still a Jackson man, but General Jackson is not; he has become a Van Buren man.”

41 Crockett’s venomous barbs were aimed at Martin Van Buren as well, whom he believed had manipulated Jackson. Crockett referred to Van Buren as the Fox, alluding to what he considered a sneaky, oily character (another nickname for him was the Magician) who would do anything for personal advancement. “The

fox is about,” he had warned in a letter published in the

Gazette, “let the

roost be guarded.”

42 Though Crockett’s attacks were public and personal, he at least couched them with an eye toward the upcoming congressional elections, hoping his complaints would show him in a positive light, making the case that it was Jackson, not he, who had changed:

He has altered his opinion—I have never changed mine. I have not left the principles which led me to support General Jackson: he has left them and

me; and I will not surrender my independence to follow his

new opinions, taught by interested and selfish advisers, and which may again be remolded under the influence of passion and cunning.

43

Those were fighting words, and Jackson interpreted them as such. Meantime, Jackson had bigger problems than one disgruntled congressman. Jackson’s administration continued to grapple with fallout over the so-called “Eaton Affair,” which had begun at the outset of Jackson’s first term the moment he selected his cabinet and appointed his reliable and dutiful understudy John Eaton as secretary of war. Eaton’s wife had died, but he had entered into a relationship with a woman named Margaret O’Neale Timberlake, herself recently widowed by her young, tall, and handsome Navy purser rumored to have taken his own life as a result of her infidelity.

44 As gossip swirled around the social functions of Washington, Jackson forcefully suggested that Eaton marry Margaret Timberlake as the honorable course of action. Eaton consented, but by now other wives within the administration had snubbed her, and many viewed this wedding as conspicuously hasty. The whole affair created internal administrative tension that Jackson hardly needed. Additionally, there were rumblings within his own cabinet on another matter, as it was becoming evident that Vice President John C. Calhoun was now actively eyeing the presidency for 1832, Jackson having intimated that he sought a single term, and no more.

45Perhaps knowing that Jackson and his core people had public relations problems to contend with, in late February Crockett generated a circular explaining his recent break with the president, as well has his failure to hammer the land bill legislation through. Ghostwriter friend Thomas Chilton certainly had a hand in the prose, which employs a clever combination of indignation and self-exoneration:

Why I have not entered into some arrangement with my colleagues to secure the land to them [his constituents]? I can only reply that I thought that I had done so. After it was ascertained that my first proposition would fail, I prepared a substitute for it, which I understood as being satisfactory—and which I again repeat I believe would have passed without difficulty, if they had not prevented me from getting the subject before the house. Heaven knows that I have done all that a mortal could do, to save the people, and the failure was not my fault, but the fault of others.

46

By this time he appeared to be reaching, however, and the squatters were primarily interested in results, not excuses. Despite Crockett’s emotional appeals, he was losing his stronghold, even in his own district, and he was clearly on the defensive.

Crockett closed his circular with patriotic language aimed at the heart, hoping for loyalty:

You know that I am a poor man; and that I am a plain man. I have served you long enough in peace, to enable you to judge whether I am honest or not—I never deceived you—I never will deceive you. I have fought with you and for you in war, and you know whether I love my country, and ought to be trusted . . . I hope that you will not forsake me to gratify those who are my enemies and yours.

47

There was no question that the circular was a campaign speech, and sincere as it may have been, many saw through the rhetoric. He was blaming others for his shortcomings, and even if his constituents believed him to be honest and trustworthy, they could also see that he was ineffectual. The Jacksonians rallied, putting forth William Fitzgerald from Crockett’s own Weakley County as their man to oppose him. They would do what they could to unseat the incumbent, and in April, Jackson himself entered the fray, taking time from his own extremely busy schedule to write his friend Samuel Hays: “I trust, for the honor of the state, your Congressional District will not disgrace themselves longer by sending that profligate man Crockett back to Congress.

48 Jackson, who typically did his best to ignore Crockett and, as a matter of course, used envoys or henchmen to do his bidding, apparently found Crockett a nettling inconvenience and wanted him out of office. That he would personally confront the matter suggests he took Crockett seriously and reckoned that he must be dealt with. It set up an ugly and bitter campaign.

Crockett was on his heels from the start, broke, in debt yet again, and behind in his electioneering, having lingered for weeks in Washington to pose for a portrait he may have been intending to use as a campaign prop. He borrowed money from William Seaton, a Whig supporter, and having finally attended to some remaining personal matters, he took the completed portrait and started home, heading overland by coach through Virginia via Maryland, eventually boarding a steamship for the final leg down the Ohio River.

49 Paradoxically, while he might have had cause for depression during the journey, knowing full well that he was in for an up-hill battle for reelection, something beyond Crockett’s power was taking hold of the American consciousness. Earlier in the previous session, people began to speak of him in metaphoric terms; a man hearing him speak at the House referred to him as “the Lion of Washington,” and added that he was practically hypnotized by his charisma and magnetism. “I was fascinated with him,” he said.

50 Visitors to the city, knowing that he lodged at Mrs. Ball’s Boarding House, would try to get a peek at this object of “universal notoriety” if they could. A newspaper article in 1831 exclaimed that he was one of the “Lions of the West,”

51 alluding to a fierce, fearless, and independent nature that led Crockett to roar his principles across the aisles. But he would need all the press he could get if he hoped to retain his seat.

Along his journey Crockett lost his new portrait, a bad omen. He arrived home fraught with fiscal worry, having been sued in April, for outstanding debts, by John Shaw, and in late May he was forced to sell twenty-five acres at his Weakley County residence to his brother-in-law George Patton. He made only $100 in the transaction, so he included Adeline, a slave girl, for another $300.

52 It wasn’t much, but canvassing required ready cash. Then, as if to bolster his own waning confidence in himself, he wrote down for the first time the maxim that would come to define his brand of “can-do” attitude, scribbling across the bills of sale for the property and the slave, “Be allways sure you are right then Go, ahead.”

53 It was as if he was convincing himself that continuing the campaign against such odds was the right thing to do.

Certainly Elizabeth would not have thought so; she had grown accustomed to fiscal irresponsibility and disaster in nearly every one of his schemes, and their relationship by now was growing distant and frayed. That he had risen in stature from regional curiosity to folk hero would have impressed her but little; Elizabeth would have seen him only as an absentee husband and father, and a financial hurricane. It did not help that the Jackson Gazette now supported Fitzgerald and began to print anti-Crockett propaganda and smears, including the recurring accusations of public indecency, gambling debts, and violent bouts of drinking. Though he had previously assured Elizabeth of his continuing sobriety, she surely must have suspected that at least some of the claims were true, much as she wanted to believe him. How could he always be so broke, always struggling to catch up, borrowing money from one man to pay off his debt to another?

Crockett had committed, however, and despite being a lone eagle now, essentially a party pariah, he went ahead with the campaign, fending off a running series, called

The Book of Chronicles, West of the Tennessee and East of the Mississippi Rivers and printed in the

Southern Statesman, that depicted his meteoric rise and cataclysmic descent. The scathing satire turned out to be the handiwork of a barrister from West Tennessee named Adam Huntsman and nicknamed “Black Hawk.”

54 Using pseudoreligious jargon and tone, the hyperbolic parodies depicted Crockett as the would-be savior of the river-country dwellers, but who had failed—so that, instead, the river people should elect Fitzgerald. Crockett hadn’t the time or the energy to parry all the attacks, but Huntsman would be a nemesis for the next few years, and Crockett would eventually have to contend with him. Crockett generated a few responses for publication in the

Southern Statesman, taking the opportunity to coin the nickname “Little Fitz” as a slam on Fitzerald, whom he accused of being base, unprincipled, and prone to gambling.

55 The insults flew back and forth, and were made particularly awkward since the men ended up touring around the district virtually together on the stumping circuit, and had plenty of face-to-face interaction. Prior to one rally in Paris, Tennessee, Crockett issued a verbal warning that if the diminutive Fitzgerald continued to make spurious charges against him, he would be forced to bludgeon him.

An expectant crowd watched and listened as Fitzgerald rose to speak, first placing a white handkerchief on the hardwood table before him. Against modest restraint by his own backers, who did not like the odds or the roughness of the place that better suited Crockett, Fitzgerald stood anyway, and promised he would verify the charges he had made against his opponent. Crockett shot up and exclaimed that he had come to “whip the little lawyer” who would continue to make such claims.

56 Eventually, as everyone in the crowd anticipated, Fitzgerald did come to the points of controversy, and Crockett flew toward Fitzgerald in a rage, storming the stand. He hardly expected what followed:

When he was within three or four feet of it, Fitzgerald suddenly removed a pistol from his handkerchief, and, covering Colonel Crockett’s breast, warned him that a step further and he would fire. The move was so unexpected, the appearance of the speaker so cool and deliberate, that Crockett hesitated a second, turned around, and resumed his seat.

57

Crockett’s backing down showed excellent common sense, but it wasn’t the behavior expected of a man with a reputation for killing bears barehanded. Embarrassed and on the defensive, Crockett resorted to lengthy and redundant anti-Jackson harangues, most lacking his patented humor and sounding mean-spirited, not his hallmarks. He continued his petty name-calling, referring to Fitzgerald as “a little court lawyer with verry little standing” and “a perfect lick spittle.”

58 Through the campaign Crockett remained true to his tenets of individuality, independence, and sticking to one’s principles no matter how unpopular they seemed. It was not enough, however, and in the end Crockett was out-campaigned by a man with backing much stronger, more influential, well financed, and more organized than his. With the infrastructure of the Jackson forces behind him, William Fitzgerald eked out a victory over Crockett in a devilishly close election, with a margin of only 586 votes out of 16,482 votes cast.

THOUGH HE SHOULD HAVE SEEN IT COMING, Crockett had not expected to lose (he never did), and he officially contested the results of the election at the next Congress, citing fraud in vote counting at Madison County, but the House Committee on Elections refused him, and the vote stood.

59 The sour Crockett had shown himself to be a poor loser, and he bowed out of Congress for the time being with anything but grace. He looked to be unraveling, his regional popularity in question (at least politically), his marital relations disintegrating, his financial situation perilous. Perhaps Black Hawk’s prediction in the

Book of Chronicles had been correct, perhaps David Crockett’s shooting star was on the wane, crashing headlong back to earth after its brief flight to fame, to flicker until it was extinguished.