ELEVEN

“Nimrod Wildfire” and “The Lion of the West”

DAVID CROCKETT HATED TO LOSE, and now it seemed that he was losing everything around him: his family, his spouse, his farm, his constituents. He had been ousted from office by a combination of his own failings and a political mechanism beyond his scope of comprehension, and he was left to pick up the pieces and try to move ahead. It would take some doing. Ironically, what Crockett failed to grasp completely was that while he struggled to maintain his political career and more important, his tenuous sense of self, something outside his direct influence was happening to his image, and to the desires of the American psyche. And he would be the beneficiary of that new hunger.

1

A few years prior, in 1829, playwright William Moncrieff had introduced a play called

Monsieur Mallet; or, My Daughter’s Letter. The play featured a notable character named Jeremiah Kentuck, played by popular actor James Hackett. The character was “a bragging, self-confident, versatile and vigorous frontiersman . . . Congressman, attorney-at-law, dealer in log-wood, orator, and ‘half-horse, half-alligator, with a touch of the steamboat, and a small taste of the snapping turtle.’”

2 The parallels to Colonel David Crockett were impossible to miss, and the play enjoyed some success. Hackett relished the role, but he wanted a play that cast him as the lead specifically, so he enlisted friend and playwright James Kirke Paulding to write a play for him. Paulding, familiar with the characteristics of Jeremiah Kentuck, sought a real-life model on which to base his play, and his muse was obvious: Colonel David Crockett. Paulding wrote his friend, the painter and writer John Wesley Jarvis, asking him to pen a few “sketches, short stories, and incidents, of Kentucky or Tennessee manners, and especially some of their peculiar phrases and comparisons.” But what he really wanted were replications, real or imagined, of the man himself. “If you can add, or

invent,” Paulding prodded Jarvis, “a few ludicrous Scenes of Col. Crockett at Washington, you will be sure of my everlasting gratitude.”

3Paulding and Hackett intended to draw their caricature, in the role of Nimrod Wildfire, directly from Crockett, borrowing from his antics and episodes in Washington, which would have been rich material. The play, which was hotly anticipated, given leaks regarding the subject matter and a widespread desire to see Crockett portrayed in this way, would be called

The Lion of the West; or, A Trip to Washington. In the play, which has the distinction of being “the first American comedy to place a crude backwoodsman in a lead role,”

4 allusions to Crockett were beyond obvious. Nimrod (the word means “hunter”) Wildfire roared around the stage clad in hunting buckskins and a hat fashioned from wildcat skin: “My name is Nimrod Wildfire—half horse, half alligator and a touch of the airthquake—that ’s got the prettiest sister, fastest horse, and ugliest dog in the District, and can out-run, outjump, throw down, drag out, and whip any man in all Kaintuck.”

5 Crockett was just egomaniacal enough to relish the connections when it finally opened, despite the fact that the farce was viewed as either mocking him, or as a “Jacksonian political piece” intended to deride Crockett and further alienate him from the Jackson administration.

6Evidently, Paulding felt that Crockett was prominent enough to warrant his blessing—or at the very least, he wished not to offend him, and on December 15, 1830, he wrote a note to Crockett, passed via an emissary, Georgia Congressman Richard Henry Wilde, assuring Crockett rather deceitfully that he had not drawn the character for comic purposes, and had no intention of making a mockery of him.

7 Crockett naïvely bought the rouse, and sent a reply to Paulding on December 22, 1830, humbly accepting his assurances that the play had no direct references “to my peculiarities.”

8 By the time the play opened in New York in November of 1831, nearly everyone knew that the overt parallels were intentional, and Crockett ended up relishing the publicity he gained from the play’s highly successful run. In fact, Hackett went on to portray Nimrod Wildfire for years, eventually taking the play across the Atlantic to London. At the moment, though, the desire for such theater simply confirmed a ravenous American appetite for characterizations of eccentric originals who had risen against unlikely odds to power and position, and who had come to represent the personality and temperament of a nation. Such people showed what was possible for common men, illustrating the achievements of “natural gentlemen.”

9Once again, just when he appeared lowest, David Crockett was buttressed by public acclaim, bucked up when it looked as though he ought to quit. The acclamation shored up his confidence when he was out of work and deeply indebted, and it gave him the notion to consider running for office again. He began eyeballing the 1833 election, writing to his financial backers in Washington to notify them of his plans and appealing to their generosity in letting his outstanding debt ride and agreeing to additional funding during his hiatus.

10 At the beginning of the new year he would write imploringly to the cashier of the Second Bank, hoping to orchestrate further bank withdrawals and suggesting that he would pay his already outstanding notes when he could.

11With some fiscal salving in place, and sights lowered on the next election, he attempted something he’d missed for the last few years—quiet and predominantly settled home life. But there wasn’t much for him to return to. Fed up with his dreams and delusions, Elizabeth had packed up and sought refuge with her more stable and solvent Patton relatives in Gibson County, taking the children with her. In Washington, Crockett had the fraternity of fellow congressmen and the social fabric of legislative life, and it would have been depressing for him to live alone on the farm, in a skeletal version of his former family life. In late August of 1831, Crockett wrote to a friend named Doctor Jones, informing him of his dire financial situation and asking for a six-year lease on twenty acres adjacent to his place on the Obion, and when Jones agreed, at decent terms and offering an option to purchase, Crockett set in to his old routine, clearing and grubbing the tough top ground, and planning a viable farm that would include a few cabins, a smokehouse, corncribs, stables, a well, and even a modest fruit orchard.

12 Optimistic to a fault, he determined to make the place flourish; perhaps if he made good on his plans, Elizabeth would even agree to move back in with him.

Whenever he could, David Crockett turned to hunting again. After being cooped up in the constrictive confines of a boarding-house room, he longed to lace up his knee-high moccasins, to pull on his buckskins and head out into the open air, cool breezes pouring down the valleys and draws, his feet padding soundlessly through dew-damp grasses as he struck for the pine forests and grapevine thickets. It would have been a difficult time for him, the loss of his people’s confidence lodged in his crop. He would have plenty of time to think about his indigent condition and what he planned to do about it. Crockett always believed optimistically that the answer to his problems lay in the land itself: that possession of it, at nearly any cost, was his path to freedom, his way out from under the ominous thundercloud of debt. If he could just get enough acreage, free and clear, he would be able to build security for himself and his family, but he also knew that time was running out. He certainly must have hoped that by the time his dreams were realized, there would be a family and friends left to share it with him.

When not out hunting or working around the new farmstead, Crockett traveled extensively through his own district, connecting with old friends and such political allies as remained after his last showing in Congress. He passed through Kentucky, and made it as far back East as Washington and Philadelphia, maintaining casual contact with potential backers, courting powerful figures like Daniel Webster.

13 Other than that, Crockett lay low, relatively quiet for a man of his notoriety. The brief caesura of 1832 to 1833 would be the quiet calm building on the national horizon before the impending arrival of the torrential David Crockett storm.

Crockett’s timing, as usual, was fortunate. When the electioneering season rolled around in 1833, he surfaced refreshed but famished, like a bear rousing from hibernation. Shaking off his slumber, Crockett would have been pleased to note that his alter ego Nimrod Wildfire had indeed caught fire, expanding Crockett’s own reputation.

The Lion of the West proved a blockbuster, drawing strong reviews and huge crowds wherever it went; even where it didn’t play, excerpts of the text were printed and reprinted in hundreds of newspapers all across the nation, including prominent papers like the New Orleans

Picayune and the St. Louis

Reveille.14 The general public began to associate Crockett with passages from the play, including variations on the boasts “I can whip my weight in wildcats and leap the Mississippi.” By April of 1833 the play had swept the nation and even leapt the mighty Atlantic, playing at the famous Covent Garden in London.

At the same time, Crockett adopted the phrase “Be always sure you’re right—THEN GO AHEAD,” which he had scribbled innocuously on two bills of sale back in 1831, as his own motto, and the aphorism stuck. He would use it as his own credo, and it defined his attitude of right and forward thinking.

15 As he had known all along, from the moment he lost the election to William Fitzgerald in 1831, he would “go ahead” and run again. Now that he had officially announced, and Fitzgerald would be his opponent once again, everyone else in the land knew it, too. And this time the tables were turned—it was Crockett’s chance to unseat an incumbent.

The electioneering during the 1833 campaign immediately took on a courteous and convivial tone, a complete reversal from the previous combat. Apparently, Fitzgerald himself, and his colleague Adam Huntsman—author of the previously damaging

Book of Chronicles—had agreed in principle to a verbal ceasefire with Crockett, each camp accepting the terms of the treaty and promising none of the dirty sabotage and mudslinging that had typified the 1831 contest.

16 For the most part the parties would stick to the truce. And if he was going to take the moral high road, to better combat the considerable opponent he knew he had in Fitzgerald, Crockett would need something to find some political nugget or vulnerability within the Jackson administration. A couple of issues and circumstances immediately presented themselves.

First, in 1832 Jackson had been elected for a second term, amid some controversy and administrative unrest. John C. Calhoun, who had served as vice president for four years under John Quincy Adams, rode his position right into the first term of Jackson’s presidency, “in an unprecedented and never repeated event.”

17 The ambitious Calhoun, himself coveting the presidency, had erroneously assumed that the gaunt and aged Old Hickory was a one-term president, and it rankled him when Jackson stuck around, and tensions strained their relationship further as Jackson began to rely on the shrewd counsel of Martin Van Buren. The division with Calhoun bore into Jackson deeply, for he was a military man who insisted on loyalty and viewed dissent as treason. Late in his life, reflecting on his presidency, Jackson made the offhand but ominous comment that his one main regret “was not having ordered the execution of John C. Calhoun for treason.”

18 When the smoke had finally cleared and Jackson’s new cabinet materialized, Calhoun was out and the slick Van Buren was in. Crockett would want to exploit the turmoil within the administration to see if he might undermine the man he now viewed as a nemesis.

This process found legs in the controversy over the Second Bank of the United States, which Crockett supported in principle, partly because the bank offered loans to cash-poor squatters who subsisted on credit to keep their meager parcels of land running, and partly just so that he might oppose Jackson, a known antagonist of the Bank. Jackson viewed the bank, which by now was headed by Nicholas Biddle of Philadelphia, as a monolithic “monster” and vowed to kill it, and stop the bleeding of the national debt in the process.

19 Jackson believed in hard currency over debt, thinking the latter contributed to economic downturns, even depressions. Crockett viewed Jackson’s position on the bank as greedy and nepotistic, and he made that case clearly and passionately in stump speeches, intimating that Jackson’s intention to remove the deposits was illegal.

By Crockett’s own admission the campaign of 1833 was “a warm one, and the battle well-fought.”

20 Though Crockett still used some scathing language (he referred to Fitzgerald as “That Little Lawyer” and Jackson’s “puppy”), he played fair, sticking to the issues for the most part, and he benefited from the fact that Fitzgerald had not succeeded in pushing through any vacant-land legislation.

Simultaneously a fortuitous series of publishing events, one of them quite likely orchestrated by Crockett himself,

21 conspired to rally support for Crockett, at the very least providing momentum for his surging notoriety. January 1833 heralded the release of a new book,

Life and Adventures of Colonel David Crockett of West Tennessee. The anonymously authored book flew off the shelves, selling out its initial print run immediately, and appearing later that year in New York and London with the revised title:

Sketches and Eccentricities of Colonel David Crockett of West Tennessee.22 Though Crockett would later use the publishing of

Life rather disingenuously as his rationale for publishing his own

Narrative, he very likely knew that the book was being written, having contributed anecdotes and factual information, and sanctioned its development and publication, knowing it stood to contribute to his reputation. In the preface to his

Narrative, Crockett made the following clever claim:

A publication has been made to the world, which has done me much injustice; and the catchpenny errors which it contains, have been already too long sanctioned by my silence. I don’t know the author of the book—and indeed I don’t want to know him; for he has taken such a liberty with my name, and made such an effort to hold me up to public ridicule, he cannot calculate on anything but my displeasure.

23

Crockett’s tongue could not have been more firmly in his cheek. It was all part of an elaborate spoof, for Crockett most certainly knew the author of the book in question, and had likely provided him, verbally, with much of the subject matter.

24 He had met Matthew St. Claire Clarke back in 1828, during the early years of Clarke’s lengthy post as clerk of the House of Representatives. Clarke was a close friend of Nicholas Biddle, president of the Second Bank of the United States, and a Whig sympathizer. Clarke was also something of a raconteur, a literary mind, and a writer.

25 Crockett liked trading stories with Clarke, and he sent personal letters to the man as early as spring of 1829, during his first term in Congress.

26 The book itself was riddled with clichés, offering little new about Crockett the man but contributing greatly to Crockett the myth. Plenty of readers made the reasonable assumption that Crockett had written the book. Though Crockett publicly scoffed at the content and pretended to be affronted by the clownish caricature it made of him, he secretly could not have been happier with the timing and the attention the work received.

Almost as if on cue, a New Englander named Seba Smith (who incidentally shared Crockett’s politics, first sanctioning and later splitting with Jackson) created a character by the name of Major Jack Downing, a down-home and likable country bumpkin who unwittingly stumbled into public life. The Portland, Maine,

Daily Courier ran the letters of Major Downing, and the Yankee audiences ate the stuff up, loving the homespun vernacular and more than willing to chuckle at the unsophisticated and unrefined mind and manners of the character.

27 The good-humored Crockett went along with the ruse, even responding to a letter from Major Jack addressing him personally and requesting that they meet in Washington to observe the political climate. An excerpt from the 1833 diary of John Quincy Adams reveals that Crockett remained playful and true to the artifice. Adams wrote that on leaving the Capitol building he

Met in the Avenue . . . David Crockett of Tennessee. I did not recognize him till he came up and accosted me and named himself. I congratulated him upon his return here, and he said, yes, it had cost him two years to convince the people of his district that he was the fittest man to represent them; that he had just been to Mr. Gales and requested him to announce his arrival and inform the public that he had taken for lodgings two rooms on the first floor of a boarding-house, where he expected to pass the winter and have for a fellow-lodger Major Jack Downing, the only person in whom he had any confidence for information of what the Government was doing.

28

Crockett must have had difficulty keeping a straight face as he related this conceit to Adams. The Downing letters became widely popular, reprinted in newspapers across the eastern seaboard, filtering across the entire country, and people immediately linked Major Jack Downing with Colonel David Crockett. The country was ready for frontier heroes, real or imagined, and Crockett filled the role as best he could, confirming in human form the desired ideals of freedom, commoner-gentleman, and values like courage and independence.

29The opportunistic Crockett took the attention and ran with it, and his campaign opponent Fitzgerald, though a strong incumbent, could do little to counter the onslaught of printed matter keeping Crockett’s name and image in the news. Commoners flocked to the polls to confirm and appreciate someone in their own mold, this bumpkin of a gentleman, this enigma named David Crockett. Crockett squeaked past in an extremely close vote, winning by a mere 173 votes out of nearly 8,000 cast, the interest in David Crockett verging on feverish. He was poised to become a cult figure, a folk hero, and bona fide celebrity, the first person in American history famous for being famous, a media-manufactured “personality” with the potential to make a living from his celebrity.

30 It was clear that Crockett had earned his celebrity status, and even had a hand in its construction. What wasn’t clear was how the notoriety would affect him, or what he intended to do with his fame. One way or another, it was time to cash in on his persona.

Crockett arrived back in Washington in November 1833 newly confident. Two years before he’d slunk home sheepishly, spiritually broken and bitter with the loss, and only a few months earlier he’d been financially strapped, paying for a crude wooden shanty on a hardscrabble tract of leased ground. His enthusiasm showed in his early arrival, well before the December 2 opening of the session. He had plenty of reason to celebrate. For Crockett, victory always salved a variety of wounds, and defeating William Fitzgerald this time around, even if by a small margin, was a kind of affirmation. But something more significant had happened just months after his successful election: members of Mississippi had come forward and requested that they be authorized to put forth his name as a potential candidate for the presidential election of 1836.

31 Could they possibly be serious? Crockett possessed enough vainglory to think so, and in his own

Narrative he alluded to it, connecting himself and the presidency several times. But at this point he would have taken the suggestion as an enormous compliment and also seen the political rationale behind the Whig courtship. After all, what were their other options?

Everyone knew that Van Buren would be offered up at the end of Jackson’s second term. He represented the moneyed, propertied class of people that Crockett outwardly criticized yet paradoxically wished to be accepted by and become a part of. His known vitriol toward both Jackson and Van Buren made him an obvious choice, and it would be impossible to find someone with greater media cachet, even if his political effectiveness was dubious. If his image and popularity could be sustained, and even expanded, over the next few years, who knew what might happen? As Crockett had proved more than once by his very presence in Washington, nothing was impossible.

At the session’s commencement, happily ensconced at his familiar lodgings in Mrs. Ball’s Boarding House, Crockett took up some old scores and readdressed one that had raged during his absence, the issue and ongoing argument over the Second Bank. Crockett’s position, and his vehement opposition to Jackson, had been faithfully trumpeted by Henry Clay, John Calhoun, and Daniel Webster, who had railed mightily against Jackson by calling him a despot, nicknaming him “King Andrew,” and aligning him with dictators like Napoleon.

32 He would let that ride for a time, concentrating his attentions instead on his old obsession: land. On December 17, he introduced a pair of motions, one proposing a select committee of seven members to investigate the most prudent and equitable method for disposal and distribution of lands west and south of the Congressional Reservation Line, and the second insuring that all files, papers, and correspondence of the House related to the Tennessee Land Bill be referred to this committee.

33Crockett’s subsequent optimism regarding the bill reveals a confidence gleaned from his recent time in the limelight, and shows that his memory for frustration, bitterness, and defeat was short. In a letter to a Tennessee constituent, Crockett rode on false hopes when he scribbled enthusiastically: “My land Bill is among the first Bills reported to the house and I have but little doubt of its passage during the present Session.”

34 His con-tinued naïveté is a bit surprising given his experience with congressional debates, the sloth of their movement, and his own history with the land issue. Still, Crockett was riding high, though his mind was elsewhere.

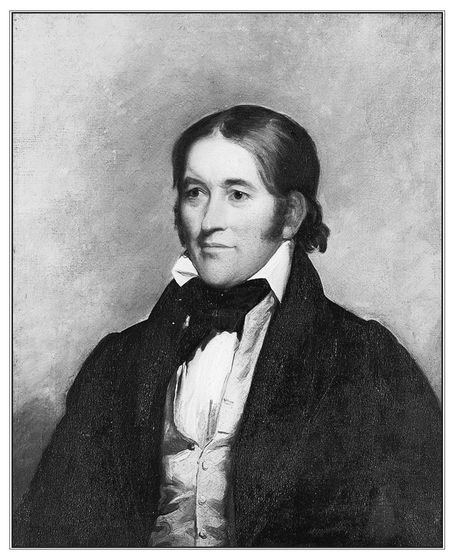

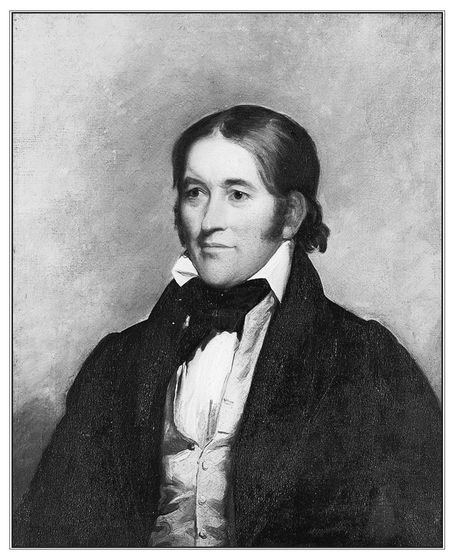

The congressman looking stately and reserved, which contrasts his actual ranting and raving behavior on the House floor. (David Crockett. Portrait by Chester Harding. Oil on canvas, 1834. Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC. Future bequest of Ms. Katharine Bradford.)

Feeling good about himself was one thing, but being financially flush was quite another, and Crockett, as he always would, retained some outstanding debt that niggled at his pride. Nicholas Biddle had been good enough to cancel one hefty outstanding note, and though Crockett was humbled and grateful, that only began to staunch the bleeding.

35 It dawned on Crockett that the series of recent literary and media events magnifying his public image and some nudging and prodding by friends and associates, as well as constituents, during the previous election cycle all conspired to an obvious conclusion: it was time to write his own story, a narrative of his life, at once to set the record straight as well as to immortalize himself in print, and if all went as planned, financial and political success was in the offing. But Crockett knew that the scope of the project was too daunting to take on alone, doubting privately whether his own literary skills were up to the task.

He turned to Thomas Chilton, fellow boarder for years at Mrs. Ball’s, his friend, confidant, and sometime ghost writer. Crockett trusted Chilton: they had come into the house together as freshmen back in 1827, and they had worked together productively before. Chilton had been trained in the law, so he could negotiate any contract with a potential book publisher. Crockett certainly took notice of the frenzied sales of both Clarke’s Life, and later the wildly successful Sketches and Eccentricities. Frankly, he was tired of seeing others profit from his name, image, adventures, and near-death escapades—he might as well taste the pie he had helped bake.

The way his image had degenerated into caricature also needled Crockett, even if he had benefited from the mirage. A narrative of his life and adventures, written in his stylized vernacular and from his unique point of view, would clarify who he was, separating the flesh-and-blood Crockett from the mythical one threatening to overwhelm him. This was his chance to decide, once and for all, how he would be perceived. “I want the world to understand my true history,” he would write, “and how I worked along to rise from a cane-brake to my present station in life.”

36 He would be puppet and puppeteer, his choice of words and the selection of his anecdotes cleverly manipulating the strings of the marionette that was his public image. Here was his opportunity to finally construct the David Crockett he wished to be, the authentic and legendary folk figure-cum-congressman, the

true “Gentleman from the Cane.” Here was his chance to portray himself “in human shape, and with the

countenance, appearance, and

common feelings of a human being.”

37 But most important of all, Crockett now understood that his fame was reaching its zenith, that the public craved him in many versions and permutations, and he desperately wished to capitalize on his popularity. One can imagine him grinning widely and with the dipped brow of feigned humility as he claims in his preface:

I know that, obscure as I am, my name is making a considerable deal of fuss in the world. I can’t tell why it is, nor in what it is to end. Go where I will, everybody seems anxious to get a peep at me . . . There must therefore be something in me, or about me, that attracts attention, which is even mysterious to myself. I can’t understand it, and I therefore put all the facts down, leaving the reader free to take his choice of them.

38

He was certainly right about everyone wanting to get a “peep” at him. Just as he was in the preliminary stages of the writing, Thomas Chilton having mailed off a flurry of prospecting letters including one to the publishers Carey and Hart of Philadelphia, James Kirke Paulding’s blockbuster play,

The Lion of the West, arrived in Washington, in its own way heralding the

arrival of David Crockett. When Crockett himself went to see the benefit performance, in a much talked-about and written-about sequence, artifice and life converged. Nearly drowned by the cheers of a knowledgeable audience, Crockett was escorted like a dignitary to a special reserved seat in the front row, center, where he waited, hoots and hollers of recognition coming from all around him. At last the curtain slowly rose, and star actor James Hackett sprang onto the stage, bedecked in the leather leggings and wildcat skin hat of Nimrod Wildfire. He stepped to the edge of the stage and bowed deliberately and graciously to Crockett, who smiled, paused, then rose and returned the gesture. The enthralled audience, bowled over by the poignancy of the moment, erupted in a frenzy of cheers and applause.

39 It was a powerful convergence of fact and fiction, where the mythical legend and the real man met, the past, present, and future of David Crockett all morphing into one. Crockett must have been intoxicated by the applause, and one had to wonder whether his addiction for that very praise would consume him the way “Arden spirits” had before.

By day Crockett attended to the mundane matters of congress, growing distracted and occasionally missing sessions; he devoted the evenings to his book. He and Chilton had agreed to a collaborative effort that would retain Crockett’s “style” and “substance,” with Crockett scribbling down the tales of his boyhood, the anecdotes, and the recollections of his life up to the present, and Chilton using his editorial eye to “clarify the matter.”

40 Probably at Chilton’s likely insistence, Crockett made sure to elucidate that his collaborator was entitled to “one equl half of the sixty two and a half percent of the entire profites of the work.”

41 He valued Chilton’s editing skills and his strong eye for structure and grammar, but he wished to retain the flavor and nuance of his own personality. Where useful and pertinent, Chilton retained Crockett’s idiosyncratic language. In the preface, Crockett humbly explained the plain style, wondering what might be criticized by “honourable men.” “Is it on my spelling?” he reflected. “That’s not my trade. Is it on my grammar?—I hadn’t time to learn it, and make no pretensions to it. Is it on the order and arrangement of my book?—I never wrote one before, and never read very many, and, of course, know mighty little about that.”

42Even in explaining the shortcomings of the book, Crockett was endearing himself to the audience. How could they not be enamored with his honesty, his candor, his utter lack of pretension? He came across as he wanted to, the “plain, blunt Western man, relying on honesty and the woods, and not on learning and the law, for a living.”

43 It was an ingenious rhetorical device, and it worked better than Crockett, Chilton, or the publishers could ever have imagined.

Crockett wrote furiously, knocking out a good portion of the manuscript by the end of January, and, finding he was quite comfortable with the task, he managed to finish well ahead of his initial deadline. But the long nights burning the proverbial midnight oil took their toll, and he fell weak and feverish once more with a touch of malarial croup. Feebly handing over his handwritten manuscript to Chilton for polishing, editing, and revising, Crockett must have been quite relieved, pleased with his efforts as a first-time writer, but with no idea of what, if anything, he had accomplished.

As providence would have it, the incomparable David Crockett had written something of a masterpiece.