TWELVE

A Bestseller and a Book Tour

A NARRATIVE OF THE LIFE of David Crockett of the State of Tennessee, Written by Himself, hit the booksellers’ racks in early March of 1834 and flew off the shelves faster than fowl spooked from a canebrake. Publishers Carey & Hart had anticipated the frenzy, having done some promotion the minute they realized they had a winner on their hands. They must have been thrilled when they saw the readable, authentic volume—tidied up by Chilton but retaining Crockett’s quaint spelling and grammar, which he had ultimately specified remain unaltered. It was a gem of a book, and they quickly made Crockett an offer by the end of January, which he accepted on February 3.

1 Mere hours after receiving his acceptance in the mail on February 7, the publishers distributed a broadside heralding the following:

It may interest the friends of this genuine Son of the West to learn, that he has lately completed, with his own hand, a narrative of his life and adventures, and that the work will be shortly published by Messrs. Carey & Hart, of Philadelphia. The work bears this excellent and characteristic motto by the author:

I leave this rule for others, when I’m dead:

Be always sure you’re right—THEN GO AHEAD!

The broadside included the very reasonable terms for what was destined to become a collector’s item: twelve copies and upwards, sixty-five cents.

2 Crockett helped his own cause as well, writing a promotional preface that he leaked to the press just prior to the book’s release.

3 Sensing interest in the narrative to be at near-hurricane levels, Carey and Hart produced the book with remarkable speed, taking it from edited manuscript to published work in less than a month. The public responded, shelling out happily for multiple copies and the first print run sold out in a matter of weeks. Carey & Hart went back to press and offered them up again. The phenomenon continued, and within a few short months the book was in its sixth printing, an undisputed bestseller.

Everyone, from statesmen to commoners, bought the book, some out of sheer curiosity, spurred by Crockett’s name and interested in his outrageous stories and tall tales. But what they all got when they opened the 211-page narrative was an American classic, an autobiography on the order of favorite son Benjamin Franklin’s. Certainly there were similarities between the two texts, and as Franklin’s

Autobiography was among the very few books Crockett owned or had ever read, he borrowed structural elements from that book.

4 But the content, and the result, was pure Crockett, with just the slightest peppering of Chilton for political effect.

Narrative is complex in its simplicity, revealing the playful, sincere, moral and even vulnerable voice of a real man, a man of his times. At once a morality tale, a political treatise, an adventure story, and a manifesto for the common man, the

Narrative was the first truly “Western” autobiography,

5 and “

the great classic of the southern frontier.”

6 The book prefigures by some fifty years the literary genre of “realism,”

7 with nothing remotely like it, or nearly as good, appearing until 1884 with the publication of Mark Twain’s

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Crockett’s

Narrative is real, vital, touching, and shrewdly humorous. It is the work of a master storyteller and truly gifted humorist.

For its apparent minimalism and straightforwardness, the

Narrative is also remarkably multifaceted, at once deliciously revealing and frustratingly obfuscating about the man David Crockett. Crockett claimed, in a letter to his son John Wesley penned during his work on it, that “I am in-gaged in writing a history of my life . . . I expect it will . . . fully meet all expectations.”

8 That the book met expectations is grand understatement, for it managed to far exceed them, giving a host of reading audiences precisely what they desired. City folks and the gentility from established centers like New York, Washington, and Philadelphia reveled in the stylized language and the original frontier humor, and the frontier folk themselves could see their own stories in the book’s narrator: a common man of humble origins and scant formal education who had risen to national prominence through his own wits, hard work, tenacity, and common sense. The book reflected their humility, decency, sense of adventure, and their role as pioneers of westward expansion. It ascertained, once and for all, that the democratic experiment of America was working and came to represent the national identity.

9The humor of the narrative prefigured and no doubt influenced the work of Mark Twain, and set a very high standard for future American humorists, precisely because it appealed to a wide range of readers.

The question of whether Crockett accurately conveyed the history of his life presents a host of vexing considerations. His recollections are uneven and evidently fabricated in a few places, and there is no doubt, given the timing of its release, that the book was politically motivated. As such, it’s a performance of sorts, playing on the desire for tall tales his readership would have expected from him, and giving him an opportunity to justify his very public break with Andrew Jackson. He cleverly avoids much discussion of his time in Congress, likely because it was ineffectual, but also since he seemed to genuinely prefer tales of his boyhood adventures and days afield to what he considered the painfully slow churning of the country’s political wheels.

It’s true that he fudged his involvement in the Creek War mutiny, probably as a way to set forth an early and justifiable animosity toward Jackson; it’s also true that he wrote of some battles in which he never took part, aware that a respected war record reflected well during political campaigns. And while he failed to include such fundamentals as the names of his own wives, siblings, and offspring,

10 he managed to infuse the text with pertinent political satire, so that the book can be read as a thinly veiled campaign circular. But those are minor transgressions given the breadth of what he managed to achieve in writing his

Narrative: a peerless American voice that stood to represent the desire of a nation. It was, and remains, a remarkable literary achievement.

Crockett hoped that it could right his listing financial ship. During the writing process he corresponded with John Wesley and mentioned that he was considering a tour in the east at recess to help promote the book, convinced that his presence would “make thousands of people buy the book.”

11 The nagging fact of his indebtedness still ate away at him, becoming an element of shame so profound that he could barely face the people he owed, and if things went well, the book might just be his ticket to solvency. “I intend never to go home until I can pay all my debts,” he told John Wesley, “and I think I have a good prospect at present and I will do the best I Can.”

12 At the same time, perhaps fired by the apparent ease with which writing came to him and the potential for profits, he conspired to help produce the first two

Almanacs, which were essentially reprinted excerpts from his autobiography and contained bear hunting yarns and other amusing anecdotes, and these he mass-marketed, producing on the order of 20,000 to 30,000 copies, many of which he hoped to sell himself along his book tour route.

13But before he could depart on his book tour, he had to face the tedium of his role as congressman, while preoccupied by the hullabaloo of the book release. The truth was that what little patience he ever possessed for the ennui of congressional proceedings was now completely gone, replaced by the very real excitement of the potentially lucrative book tour, and a feeling of importance, perhaps even superiority, at the attention his book won him. His behavior on the House floor, which had grown progressively more “eccentric” and idiosyncratic over the years, now bordered on erratic and even unstable. Fueled by the controversy over Jackson’s removal of the bank deposits between sessions, Crockett launched into scornful rants, becoming disorderly, breaching the decorum the congressional halls demanded.

His verbal assaults grew hackneyed, for he and others had used many of them before, describing Jackson in hyperbolic epithets like “King Andrew,” and even aligning him with dictators and despots, remarking in a letter to friend William Yeatman:

He [Jackson] has tools and slaves enough in Congress to sustain him in anything that he may wish to effect. I thank God I am not one of them. I do consider him a greater tyrant than Cromwell, Caesar or Bonaparte. I hope his day of glory is near at end! If it were not for the Senate God only knows what would become of the country.

14

Crockett’s public seething managed to get attention, and had the effect of keeping his name in the papers, cementing his reputation in politics as one of Jackson’s most vehement critics. Seeing that any movement on his lame land bill appeared remote, Crockett achieved the nearly inconsequential victory of procuring postal service for diminutive Troy, Tennessee, through Obion County.

15 Other than that, he effectively ignored the business of Congress and, as a result, the desires of his constituency, focusing instead on himself and the business of solidifying his name and image in the popular consciousness.

He was so impatient, so intoxicated with stardom that he did not even wait until the end of session to begin the process. He would leave smack in the middle of the session, despite some earlier criticism about his tendency toward absenteeism. But before he left, there was some socializing to do, and Crockett hooked up with his old pal Sam Houston, who was in Washington after his self-imposed exile among the Cherokee. The two were seen at parties, dinners, and in the company of a woman named Octavia Walton, whom Houston was apparently courting and whose guest book each signed while they visited and shared drinks.

16 Houston was in town on official business, having recently come from Texas, which he likely told Crockett was ripe for the picking. He may have reiterated what he had recently told James Prentiss: “I do think within one year it [Texas] will be a Sovereign State and acting in all things such. Within three years I think it will be separated from the Mexican Confederacy, and will remain so forever.”

17 Houston understood firsthand already what Crockett would later see—that Texas offered the newest frontier of the West, where opportunistic men, in the right place at the right time, might make their fortunes.

As they reminisced about old times and pondered the future, Houston must have described to Crockett the wild and undeveloped hunting grounds and the seemingly endless expanses of land for the taking. Houston was utterly intoxicated with Texas, his unbridled enthusiasm evident in a note to his cousin some months before: “Texas is the finest portion of the Globe that has ever blessed my vision.”

18 The prospects in Texas would have piqued Crockett’s interest considerably. They parted ways, perhaps with plans to meet again in Texas.

Plagued as he had been over the years by relapses of malaria, Crockett could sometimes use his health as a fairly legitimate excuse for his tendency to be a congressional truant, and when he was later criticized for packing up and going on a “Towar Through the Eastern States,” he would play the health card once again. But he fooled no one. There were other factors at work as he departed Washington on April 25, 1834, later ensconcing himself in Baltimore’s Barnum’s Hotel and preparing for a lovely meal with Whig cronies to discuss his upcoming tour. He had already intimated to John Wesley that he intended to advance book sales through public appearances, and on April 10 he wrote a letter to Carey and Hart requesting 500 copies of the book that he could take along and peddle on his own.

19 His Whig friends and political supporters had arranged an elaborate speaking tour and public appearance itinerary for him, and the shrewd, innovative, and media-savvy David Crockett figured to hawk as many books along the way as he possibly could, creating what was the first ever official “book tour.”

20It was at once a stroke of marketing genius and political suicide.

GETTING OUT OF WASHINGTON would have been a great relief to Crockett, and the trip was one of the most delightful and electrifying he ever made, as he was paraded, wined, dined, and fêted through the most vital cities along the eastern seaboard, including Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. It was a highly structured and tightly monitored publicity tour orchestrated by the Whigs, who were trotting Crockett out to see how he played, the better to determine whether the obstinate and headstrong frontiersman-cum-congressman and a noted loose cannon might prove malleable enough to make presidential material two years hence. Massive crowds turned out at every stop along the way, all hoping to get a glimpse of the American original, all hoping to hear him utter some outlandish anecdote. For the most part, he did not disappoint, though he was also expected by the Whigs to come out in defiance of Jackson and Van Buren, pacifying partisan crowds with practiced rhetoric, including the old contention that “I am still a Jackson man, but General Jackson is not.”

In Baltimore, he gave a speech in the affluent community of Mt. Ver-non Place beneath a statue of George Washington.

21 He then boarded the steamship

Carroll-of-Carrolton, which bore him across the Chesapeake, then went by train to Delaware City, and “re-embarked there for a trip up the Delaware River, and arrived in Philadelphia that evening, April 26.”

22 The tour was well conceived, with adoring, cheering throngs greeting him at every stop along the way.

President Andrew Jackson, Crockett’s archnemesis. Of their political rift Crockett would claim, “I am still a Jackson man, but General Jackson is not.” (Andrew Jackson. Portrait by Albert Newsam, copy after William James Hubard. Lithograph, print 1830. Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC.)

In Philadelphia, Crockett made a brief speech and was then paraded to a hotel directly across the street from the United States Bank, certainly no mere coincidence. In the next few days he was whisked about the city, touring the civic waterworks, the asylum, the Navy Yard, the stockyard, the mint, and the exchange, where as requested he launched into his patented anti-Jackson oratory.

23 Prominent young Whigs of Philadelphia presented the beaming Crockett with a watch, chain, and seal bearing his now-famous motto, “Go Ahead,” and offered him the present of a new rifle, to be delivered upon completion to his personal expert specifications. It was the perfect gift for a man whose reputation had been made in part by his skills with the long rifle, in target and sport as well as in the pursuit of wild game.

On April 29, Crockett left Philadelphia for New York, sailing (for the first time) up the Delaware on the

New Philadelphia, then boarding a train and crossing northern New Jersey to Perth Amboy, where he changed trains to New York City.

24 The pace and schedule in New York were just as frenzied as in Philadelphia, but this fit with Crockett’s solidifying persona of politician, celebrated personality, and author. Crockett’s predictions and projections about his tour, and the effect it would have on his book sales, were fairly astute and accurate. While in Philadelphia, he had briefly met his publishers and coordinated a print run of 2,000 copies of his

Narrative, to which they agreed. Sales were booming.

25On arrival in New York, Crockett was met by a knot of young Whigs who boarded the train and treated him like the dignitary he was, shepherding him to his opulent lodgings at the American Hotel, where he would remain comfortably, but breakneck busy, for nearly a week. On his first night in New York he took in a burlesque show, complete with slap-stick sketches, dancing, and ribald comedy. The next day, moderately rested, Crockett rose and was brought to the New York Stock Exchange on Wall Street, where he delivered a prearranged speech. The highlight of the day came when he took lunch with Seba Smith, the creator and author of Major Jack Downing. The two men must have shared some amusing banter, agreeing that their literary alter egos would exchange letters in the

Downing Gazette.

26 Later in the afternoon he visited Peale’s Museum of Curiosities and Freaks, where he witnessed scientific specimens the likes of which he had never encountered, and watched a ventriloquist, which dazzled and amazed him. The ventriloquist was also a magician, and he performed a few tricks, including making money disappear and magically reappear. Crockett used the moment to master his own comic timing, as he quipped jokingly, “He can remove the deposits better than Old Hickory.” The assemblage erupted with hoots, laughter, and applause.

27That evening Crockett was treated to a banquet that included esteemed colleagues and fellow supporters of the United States Bank. Among them was Gulian Verplank, the man who had defended Crockett’s conduct, and by extension, his honor, back in 1828 when he wrote the letter assuring Crockett’s gentlemanly behavior at the Adams’s dinner. Also in attendance was Augustin Smith Clayton, the probable author (though the book was published in Crockett’s name) of the spurious

Life of Martin Van Buren, Hair-Apparent to the “Government” and the Appointed Successor of General Jackson.28 Clayton gave a short speech, followed by Crockett, who by now must have been a bit travel weary despite the excitement of his surroundings. On May 1 Crockett visited various newspaper offices and met with their editors, then toured the noted Sixth Ward.

Though he knew that the tour was bolstering book sales, his enthusiasm for making canned speeches and serving as puppeteer for Whig party propaganda began to flag, and he balked at a well-advertised and well-attended appearance at the Bowery Theatre. After some coaxing by his hosts, Crockett agreed to a brief visit, after which he abruptly adjourned to his lodging—he may truly not have felt well.

29 A good night’s rest revived his spirits, and the next day he participated happily in a shooting match and demonstration in Jersey City, which cheered him up and perhaps reminded him why he was there in the first place—for himself, to elevate and cement his public persona. The Whigs had different ideas, of course, and perhaps through his obstinacy and behavior in the Bowery they began to see that his independence might prove too roguish to rein in. Perhaps he was not as politically or personally pliable as they had hoped. Still, the gunplay and hunting demonstration encouraged Crockett, and in the late afternoon he boarded a steamship bound for Boston, via Newport and Providence, brief stops where Crockett waved and bowed to applauding masses.

It was now time to go through a similar meet-and-greet routine in Boston. Between speaking appearances he also visited factories, including one in Roxborough, where the owner gave him a fine hunting coat manufactured on the premises. He now had a fitted rifle and a new hunting coat, and had recently been shooting, all of which would have reminded him of his home in Tennessee, where he had not set foot in many months. On May 7, Crockett visited Lowell to see the mills and was given a tour by textile tycoon Amos Lawrence, a proud and dignified captain of industry. Lawrence presented Crockett with a finely tailored domestic wool suit fabricated by Mississippi haberdasher Mark Cockral.

30 That evening, Crockett dined with “one hundred” Lowell Whigs and spoke in glowing terms of the cleanliness, quality, and beauty of the manufacturing operation and its products and materials, even “praising the health and happiness of the five thousand women toiling in the mills.”

31This first phase of the tour was drawing to a close, but as the Whigs wished it to end on a high-profile note, they had arranged for Crockett to dine with Whig luminaries at the lovely home of Lieutenant Governor Armstrong. After dinner, Crockett was taken to a theater, for the purpose, as he put it, “to be looked at.”

32 He must have begun to feel like one of the specimens on parade at Peale’s Museum of Curiosities and Freaks, with people standing shoulder to shoulder just to get a look at him. It would have been simultaneously flattering and taxing, for Crockett truthfully did value his freedom, and he would have sensed that the Whigs were manipulating him for their own purposes. For now, he was willing to go along with the ruse, since he stood to gain from the media attention.

Crockett had been hosted in first-rate manner throughout the tour, and Whig supporters picked up every dinner tab and bar bill, even paying for his accommodations. He was likely also supplied with spending cash, “handshake money” designed to keep him flush. Despite the accolades, the frenzied book sales, and the star treatment, he would have been relieved to be making the return trip toward Washington, with just a couple of mandatory stops along the way. After declining an evening of dining and speaking in Providence, Crockett acquiesced in Camden, New Jersey, where he sermonized for “about half an hour” before a large and appreciative gathering, then boarded a boat for Philadelphia.

33 Back again in Baltimore, the tour having come full circle, Crockett met a massive and adoring horde, many of whom followed him to his lodgings at Barnum’s Hotel, where he made yet another speech and waved good-bye to his fans, relieved for this leg of the tour to have concluded. He limped back into Washington on May 13, drained from the sheer pace of the trip, and perhaps a bit self-conscious about whether or not he had compromised his own principles. Part of his speech along the way had included the conviction that he was “no man’s follower; he belonged to no party; he had no interest but the good of the country at heart; he would not stoop to fawn or flatter to gain the favor of any of the political demagogues of the present time.”

34 It would take tremendous denial not to see the irony in such claims, as it certainly appeared that David Crockett was in cahoots with the Whigs, despite claims of being a man bowing to no party. They had auditioned him to see how he might play two years later. If he proved not to be potentially “presidential,” that was okay, too. At least he had served to publicly criticize the Jackson administration at every stop. It had been a very clever scheme on the part of the Whigs, with virtually no downside.

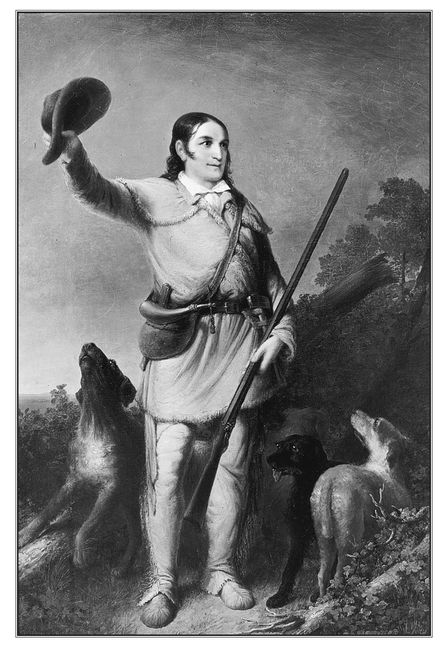

35Fresh from his whirlwind tour and feeling haggard but still quite full of himself, Crockett agreed to sit for a portrait by the painter John Gadsby Chapman. Crockett had lost one portrait previously, unfortunately leaving it on a steamboat, and the others he had sat for in the past few years had failed to impress him much, or, to his mind, capture his likeness in a convincing and—perhaps more important—memorable fashion. Crockett found the previous portraits too formal, making him appear, as he put it, like a “sort of cross between a clean-shirted member of Congress and a Methodist Preacher.”

36 He decided he could help orchestrate the image, in effect becoming the costume designer and art director for the project, and Chapman gave Crockett full rein. Crockett launched enthusiastically into the work, thrilled by the collaborative possibilities: “We’ll make the picture between us,” he told Chapman, it would be “first rate.” Then epiphany hit Crockett like a flash of lightning in a hurricane—the best portrait for posterity, the one he wished to be remembered, was out hunting in a “harricane,” dressed in full leathers and regalia, with all his hunting gear, tools, long rifle, and a team of likely hounds. Such a scene would be destined to “make a picture better worth looking at.”

37Crockett took the task of this image-making very seriously, searching out the best and most authentic props: leather leggings, a worn and faded linsey-woolsey hunting shirt, a battered powder horn, a hatchet or tomahawk, a butcher knife, and a pack of scurvy-looking dogs that appeared worn from the hunt. Finally, Crockett coordinated the pose itself, choosing one of action, the hunt about to begin: his felt hat in his right hand, the dogs dashing and yelping underfoot, one looking up expectantly for the word to go ahead, Crockett’s gun cradled confidently in the crook of his left arm.

38 It was the Crockett his adoring public wanted to see, not a stuffy, clean-shirted member of Congress, not a fancy gentleman dressed for an evening of society, but a rough-and-ready backwoodsman, the man who had years before poked his inquisitive head out of the Tennessee canebrakes “to see what discoveries I could make among the white folks.” He had discovered much, not the least of which was the uncanny ability to participate in the making of his own mythology. The image would complement his book, and the publicity from the tour, quite nicely.

Congressman David Crockett in full hunting regalia and with bear-hunting dogs, immortalized in the image he helped to create. (David Crockett. Portrait by John Gadsby Chapman, 1834. Oil on canvas. Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, Austin.)

Between sittings, Crockett went through the motions of his congressional duties with an animosity toward Jackson that was reaching maniacal proportions and a bilious disdain for the entire governmental process. His verbal assaults now breached all sense of decorum, and on more than one occasion the Speaker of the House was forced to call the fuming Crockett to order.

39 To make matters worse, the land bill, on which Crockett had hung practically his entire political reputation and life, was dead in the water. As the session drew near a close, on June 9 he scribbled an angry and disillusioned letter to William Hack, revealing that what little hope he had possessed now flagged. “We will adjourn on the 30 of June So I fear I will have a Bad Chance to get up my land Bill I have Been trying for some time and if I Could get it up I have no doubt of its passage.”

40 He was right about that.

He would be thwarted for the remainder of his term, until he remained nothing but a raging cipher in Congress. In late June he erupted, calling Jackson’s advisors

a set of imps of famine, that are as hungry as the flies that we have read of in Aesop’s Fables, that came after the fox and sucked his blood . . . Let us all go home, and let the people live one year on glory, and it will bring them to their senses . . . Sir, the people will let him know that he is not the government. I hope to live to see better times.

41

He had unraveled completely. Seeing him leaving the Capitol for home one day, Chapman, who had been painting him for weeks, remarked that he appeared “very much fagged” (exhausted).

42 Adding salt to his wounds were the growing criticisms of his absence from Congress for those weeks during the tour, which he attempted to salve by claiming chest pains. “I had been for some time,” he wrote in a lame defense, “labouring under a Complaint with a pain in my breast and I Concluded to take a travel a Couple of weeks for my health.”

43 But no one was fooled, as his movements and appearances across the eastern seaboard had been widely published in the

Niles Register and in many other papers across the country. His constituency began demanding answers, and without the passage of his vaunted land bill, he had nothing but excuses to offer them.

Flabbergasted and clearly at his wits’ end, Crockett exclaimed, “I now look forward toward our adjournment with as much interest as ever did a poor convict in the penitentiary to see his last day come.”

44 So anxious to escape his prison without bars was Crockett, he bolted even before the official adjournment of the session, determining to head back to Philadelphia to visit Carey & Hart, hawk a few more books along the way, pick up the rifle he had been fitted for, and surround himself once again in a cocoon of adulation, where his popularity knew no bounds.