FIFTEEN

“ Victory or Death”

IT WAS TIME TO RIDE, to muster and mount and begin the long march—some 300 miles—toward the Rio Grande. For the last few days, ever since signing the oath that made him a soldier once again, Crockett had seen others follow suit, some inflamed by the call to arms, some, as he was, lured by the land and the freedom it symbolized. The land that stretched out before them appeared vast, subtly undulating grass prairie ground, so limitless that Sam Houston had written of it three years before, commenting in a letter to Andrew Jackson, “I have traveled five-hundred miles across Texas, and there can be little doubt but the country east of the Grand River . . . would sustain a population of ten millions of souls.”

1 Now a steady stream of those souls poured through Nacogdoches, and the steadfast and the hearty took the pledge and armed for inevitable battle.

Officially, David Crockett held no military rank, but that did not keep the small band of volunteers who began to huddle around him from appropriating him as their de facto leader. Abner Burgin and Lindsey Tinkle, with him at the start, appear to have begged off and headed home back to Tennessee, but flanking Crockett were his loyal nephew William Patton, his cousin John Harris, his buddy Ben McCulloch, and other men including Daniel Cloud, Jesse Benton, and Peter Harper. Perhaps to honor their adopted leader, they nicknamed themselves the Tennessee Mounted Volunteers.

2 There was much to do, and Crockett took charge, drawing on his expertise, still there after lying dormant for twenty-odd years, in planning to lead a small band of scouts into hostile and foreign wilderness. He procured a canvas tent to shelter his men from the biting winds and rain they might encounter, though he personally preferred to sleep under the stars whenever possible.

3 Broke as usual, perhaps as the result of buying extra rifles for the Choctaw Bayou hunt,

4 Crockett struck a deal with the government to purchase for $240 two of his long guns, some of his on-hand equipage, and the chestnut he rode, though only a very small percentage of the money was given him in cash—the remainder due him scribbled on a promissory voucher.

5 He organized what further provisions he could, and by January 16 the mustered Tennessee Mounted Volunteers were ready to ride.

Perhaps sensing that it would be his last chance for a good long time, before Crockett left Nacogdoches he had stolen some private time to finish his letter to his daughter, his prose imbued with tenderness and hope, and yet his final words reflect his understanding that there might be cause for his relatives to be concerned about him. He tried to assure them that everything would be fine: “I hope you will do the best you can and I will do the same. Do not be uneasy about me. I am among friends. I will close with great respects. Your affectionate father. Farwell”

6And with that he slid his boot into the stirrup, slung his forty-nine-year-old frame once more into the saddle, reined his horse tight and clucked the tall steed forward. True to his own motto, he was going ahead, this time to the Texian revolution, riding headlong toward destiny.

CROCKETT AND HIS COMPANY rode La Bahia Road unhurriedly, south toward Washington-on-the-Brazos, stopping to hunt when game flushed from cover or broke from the timber, which now grew sparser and diminished behind them. Some of the men decided to detour and go gander at the rumbling Falls of the Brazos, rumored to be magnificent.

7 Crockett kept on, agreeing to rendezvous with the other boys in Washington, and the marshy terrain they soon encountered would have reminded him of the bogs and swamps he had scouted in Florida. The horses lurched and squelched through miles of mucky pools, the sulfurous stench rising like steam around them, until they finally broke onto the banks of the Rio de Brazos de Dios, the far-reaching River of the Arms of God.

8When Crockett and the four men still with him crossed the muddy Brazos and rode into town, they found a frontier outpost literally hatcheted from river woods, immense stands of towering oaks and hickories; the newly hewn town of some 100 residents still riddled with the stumps of recent cuttings.

9 Crockett may well have expected to find Houston there, but their paths failed to cross, as Houston was off negotiating a deal with the Comanche not to interfere with the colonists,

10 and he would not arrive in Washington until March 2.

11 They had taken their time getting here, meandering as did the riverbanks they rode. He would hole up in Washington for a couple of days to rest and see what he could learn about the military situation, and find out where he might be needed.

What he learned upon arrival, and what Houston had recently discovered as well, was that the situation in San Antonio de Béxar had become grave. Colonel James C. Neill, who had been left with just a hundred or so men to guard San Antonio, which they had secured in a brief skirmish December 5, scratched out an urgent message to Houston on January 14. He explained that the conditions at the garrison were worsening, and he had received reports that Santa Anna moved north toward the Rio Grande with a large army, and that he could be attacked in as few as eight days.

12 Given the news, Houston had quickly dispatched James Bowie and a modest company of men to Béxar to shore up Neill if he could. Houston also made it clear that he wanted “the old Mexican fortifications in the town demolished so they would be of no use to the enemy,”

13 and that in-cluded the Alamo, an old Spanish mission being used as a fort, if necessary. But when Bowie reached Béxar, he found that Neill had done a superb job fortifying the garrison, buttressing the walls of the Alamo, strengthening the gun emplacements, so that upon reviewing the compound with Neill, the two men decided that in fact Béxar could be held, especially with the cannons seized in December.

14 With an injection of fresh volunteer troops, they reckoned, San Antonio could be defended for a time, anyway.

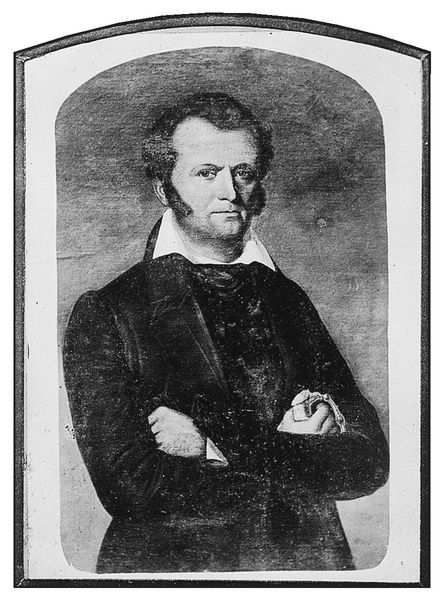

Notorious James Bowie of Louisiana led the volunteers at the Alamo until illness confined him to his quarters. (Portrait of James Bowie from glass plate negative. Lucy Leigh Bowie papers, Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library, San Antonio.)

Crockett was not the kind of man to panic or shirk danger, though upon hearing about the likely convergence of Mexican forces from the north, and Houston’s recently dispatched units heading south, his dander would have been up. He did not rush from Washington, and perhaps awaited specific orders with his small company, including John Harris, his cousin, and fellows Daniel Cloud, B. Archer Thomas, and Micajah Autry, the rest having not arrived from their split as yet.

Crockett rode out to Gay Hill, not far from town, on the afternoon of January 24, and on reaching the homestead of James Swisher he saw a man on horseback arriving with a deer slung behind his saddle, a familiar and intriguing sight for Crockett. It was Swisher’s son, John, then just seventeen but already quite skilled with his rifle. Crockett assisted the youngster in heaving the deer from the horse, complimenting the boy on his handsome trophy and asking to know the details of the shot and kill, the sorts of woodsy stories which always interested him. Impressed with the young man, who perhaps reminded him of his own boyhood, Crockett began calling John Swisher his “young hunter,” and in fun, he even challenged the lad to a shooting contest.

15 The young man was so taken by the attentions that he claimed he “would not have changed places with the president himself.”

16Crockett spent a few days there, and his hosts recalled that during that time they never let him get to bed before midnight or one in the morning, so enthralled were they with his stories and his manner. “He conversed about himself in the most unaffected manner without the slightest attempt to display any genius or even smartness,” John recalled fondly, adding, “He told us a great many anecdotes, many of which were common place and amounted to nothing within themselves, but his inimitable way of telling them would convulse one with laughter.”

17 The Swisher family was quite honored to have the distinguished man in their midst, if only for a short time: “Although his early education had been neglected, he had acquired such a polish from his contact with good society, that few men could eclipse him in conversation.”

18 As he did with nearly every person he ever met, David Crockett left an indelible impression on the Swishers before it was time to saddle up and ride again.

The Swishers came out to watch Crockett and B. Archer Thomas ride away, feeling a mixture of admiration for the legend and regret that he had to go. The man they waved to from their home seemed more mortal than legend: “He was stout and muscular, about six feet in height, and weighing 180 to 200 pounds. He was of florid complexion, with intelligent gray eyes. He had small side whiskers inclining to sandy. His countenance, although firm and determined, wore a pleasant and genial expression.”

19 Despite heading into the unknown, which very likely included being in harm’s way, Crockett maintained that infectious conviviality, that joy in being alive.

DAVID CROCKETT did not look like much of a soldier as he made the final leg of his journey south, and neither did his riding companions. None of them had official uniforms, instead riding in what civilian clothes they had, some in tanned leather leggings and “buckskins,” traditional utilitarian frontier garb or “leatherstockings.”

20 The men traveled with all their belongings tied behind their saddles, extra clothes and a bedroll and perhaps some scant provisions in saddlebags, heading into biting winds and driving winter rains, their fur hunting hats pulled down over their ears in the cold mornings and evenings.

21 The terrain grew ominous, and about three days’ ride from Washington the men would have passed through the massive, eerie forest of Lost Pines.

22 They rode through Bastrop

23 and Gonzales, finally arriving in San Antonio de Béxar and dismounting under a steady drizzle in a Mexican graveyard west of the main town, where they took shelter.

24 Before long, someone sent word to James Bowie that a small knot of riders was at the graveyard, and Bowie himself, accompanied by Antonio Menchacha, rode out to find out who had arrived, hopeful of reinforcements.

25 They found David Crockett and his little band of Tennessee Mounted Volunteers, their number now reduced to just five. Bowie and Menchacha escorted Crockett and his boys into town, taking him directly to the home of Don Erasmo Seguín, one of San Antonio’s most prominent citizens.

26 Crockett would stay there, hosted warmly and treated well, until he took lodgings off the main plaza.

Crockett’s arrival obviously created a buzz around the township and the garrison, both his celebrity status and his military experience as a scout boosting morale. Though he likely had no desire to be incognito anyway, shortly Crockett was asked to make a speech and he consented, and by the time he arrived at the main plaza an expectant audience awaited. Colonel James Clinton Neill had rounded up men from the garrison

27 and locals flocked curiously around as Crockett mounted a dry-goods box that had been placed for him to stand on as the applause rose. According to Dr. John Sutherland, who recorded the events of that day, after the initial cheering died down and the assembled crowd realized it was really the flesh-and-blood Crockett standing before them, a “profound silence” fell over the crowd as they waited for him to speak. At last he spoke, opening with light yarns and transitioning into his patented “you can go to hell” anecdote, then becoming serious once the laughter subsided. “Fellow citizens,” he assured those he had ridden so far to join, “I am among you.” He must have meant this figuratively as well as literally, even spiritually. According to Dr. Sutherland, Crockett went on in this vein: “I have come to aid you all that I can in your noble cause. I shall identify myself with your interests, and all the honor that I desire is that of defending as a high private, in common with my fellow citizens, the liberties of our common country.”

28 Crockett closed with the assurance that he would do whatever it took to help, and that he expected no special treatment or honors: “Me and my Tennessee boys, have come here to Help Texas as privates,” he told them with honesty and conviction, “and will try to do our duty.”

29 It was all anyone could have asked of the man.

Two nights later, a bona fide shindig was organized, in good part to honor the arrival of the famous Tennessean David Crockett. The affair was well-attended, including several prominent Tejanos, among them Antonio Menchacha, who had been kindly urged to bring with him “all the principal ladies in the City.”

30 William Barrett Travis, James Bowie, and other officers were there as well, enjoying the entertainment which included the seductive fandango, a style of dance more provocative than the Americans volunteers would have been accustomed to. They were riveted by the pulsing beat, the foot stomping, the swirling dresses of the exotic women. The party blended into a mixture of frontier stomp-down and Mexican fandango inside the ballroom, with everyone feasting and drinking with relish. Around 1 a.m., a lone horseman thundered into town, the clatter of hoofbeats mixing with the music as he skidded to a halt and brought forth the most recent courier report from the south of the Rio Grande. The envoy, sent by Placido Benavides, “the Alcade [mayor and magistrate] of Victoria and now employed by the Seguíns as a spy, arrived at the ballroom requesting to speak with Captain Seguín.”

31 Learning that Seguín was not available, Menchacha agreed to receive the message.

Interested, Bowie approached Menchacha, who pored over the contents of the letter. His eyes narrowed with concern, Menchacha passed the missive to Bowie, who scanned it quickly. Bowie tried to hand the letter to the passing Travis, but Travis quipped that he was otherwise engaged, currently dancing with the most gorgeous woman in San Antonio, and he had no time for reading letters. Bowie frowned, insisting that he might be interested enough to hold off on the dance. With others, including Crockett, huddled excitedly around, Travis read the contents aloud. Ten thousand men, led by their chief, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, were marching on San Antonio, with the sole intention of seizing it. The note was four days old, which meant that, depending on their pace over the roughly 150 miles remaining, the Mexicans would be there in less than two weeks.

32It was a fantastic party, and it was by now quite late. Many of the men were already drunk. There was no point in breaking up the festivities. “Let us dance to-night,” Travis hollered, perhaps hoping to rally the men and keep morale high, “and to-morrow we will make provisions for our defense.”

33 The men returned to the ladies, and the dancing went on until sunrise.

Although J. C. Neill had done a remarkable job of maintaining order, morale, and a semblance of military discipline around the garrison, there were still rumblings about the camp—disgruntlement over lack of pay and provisions—and some men were planning to bolt if things did not improve soon. Neill’s abilities and leadership moved Bowie to write, “I cannot eulogise the conduct and character of Col. Neill too brightly,” he said, adding that “no other man in the army could have kept men at this post, under the neglect they have experienced.”

34 His skills and competence made the news of his departure tough for Bowie to take; on February 11, Neill departed abruptly, citing a sudden illness in the family and a special mission to procure defense funds.

35 He requested a “twenty day’s leave,” and officers and volunteers alike pleaded with him to stay, but his mind was made up. As he readied to ride off, Neill assigned William Barrett Travis the command of the garrison.

Travis, who had arrived only a week or so before and was a mere twenty-six-year-old stripling, did not immediately command the respect of the troops. In fact, many felt that the older, more experienced local Jim Bowie to be the obvious choice. Bowie had deep ties to San Antonio, having taken full citizenship back in 1831 and married the daughter of the town’s richest family—the Veramendis.

36 As a result, Bowie was well known about the place, and the men liked his festive side, too. A hard drinker and storyteller (he was rumored to have wrestled alligators in the Louisiana of his youth), Bowie assumed that the command of the Alamo would be his. The volunteers and the mercenaries preferred Bowie’s command, while the regulars—what few there were of them—opted for Travis. Travis saw that he was in a precarious situation, and immediately called for an impromptu company election. Some of the volunteers actually suggested that Crockett should be included because of his obvious war experience and clear leadership abilities, but he diplomatically declined, citing his intention only in assisting Travis.

37The ballots were quickly cast, with only two volunteer companies voting. Bowie was elected,

38 but as it was barely a majority, and allegiances were clearly split between him and Travis, the reality was that no one was technically in command, the camp now divided in two. Bowie decided to celebrate his “victory” by launching into a powerful two-day drunk, carousing wildly about the town. He stumbled to the jail and released Mexican prisoners, then commanded his followers to halt a massive, ox-drawn cart filled with fleeing civilians, afraid of the advancing Santa Anna forces. Violently asserting his control, Bowie crazily ordered the Tejanos to return to town.

39Travis was disgusted by the despicable behavior. He wrote to Governor Henry Smith, complaining of the situation: “Since the election [Bowie] has been roaring drunk all the time. If I did not feel my honor & that of my country compromitted I would leave here instantly for some other point with the troops under my immediate command—I am unwilling to be responsible for the drunken irregularities of any man.”

40 In fact, seeing that Bowie’s behavior was beginning to infect the other men as well, as many of the garrison were now drunk, too, Travis made a shrewd decision and ordered the regulars to follow him to an encampment on the Medina River a few miles from town where order could be restored.

41His sensible tactic worked, for two days later, on February 14, a sober and contrite Bowie offered apologies for his erratic behavior, though by now he was falling feverishly ill, his head throbbing. The two came to a compromise: Bowie would lead the volunteers of the garrison and Travis would remain in command of the regulars, plus the volunteer cavalry, a joint command, with all correspondence and orders signed by both of them.

42 They wrote Governor Smith urgently requesting money, supplies, and munitions, and expressing hope that they would get them soon. Though they did not know exactly when Santa Anna and his troops would arrive, they could practically feel the force’s hoofbeats rumbling their way. “There is no doubt that the enemy will shortly advance upon this place,” they wrote together. “We must therefore urge the necessity of sending reinforcements as speedily as possible to our aid.”

43 Travis moved back into lodgings inside town, and Bowie and his volunteers boarded at the Alamo compound. They were committed to the fight, and had silently agreed that they would die fighting for Texas if necessary.

Crockett moved into the Alamo with the rest of the volunteers, busying himself by helping as he could to shore up the defenses of the abandoned mission. When time permitted, he visited with volunteers, told jokes and stories, trying to keep morale high, even when the mood among the famished and ill-provisioned camp was low. Crockett had felt want as a soldier before, remembering all too well those anguished days plodding near dead through the Florida swamps. He would cheer up the men with his witty and outrageous stories. If Crockett had known what was coming, he might have been less jovial.

On February 16, Santa Anna crossed the Rio Grande at Paso de Francia, immediately predicting that the Texians anticipated his arrival from the south, by way of the Laredo Road.

44 Instead, he would swing around to converge on San Antonio de Béxar from the west. During the journey north, Santa Anna’s army had grown, and when he had met Cós’s retreating force of 815 poorly armed and poorly clothed soldiers, he annexed them straight away, ordering them to turn around and head toward San Antonio once more. Then Santa Anna “angrily ordered Cós to violate the terms of his parole, that is, that he would not bear arms against the Anglo-Americans.”

45 These haggard men, as well as those of General José Urrea, whose 550 men had crossed the Rio Grande at Matamoros on February 17,

46 would converge on Béxar and catch the Texians by surprise. They rode hard through plunging temperatures and a threatening sky filled with pounding hail and snow. José Enrique de la Pena, an officer in Santa Anna’s army, described the macabre scene, swathed as their men were in “torment and cold”: “What a bewitching scene! As far as one could see, all was snow. The trees, totally covered, formed an amazing variety of cones and pyramids, which seemed to be made of alabaster.”

47 The weary men pressed on, riding through the bizarre spectacle riddled with dead and dying mules, horses, and men, the snow “covered with the blood of these beasts, contrasting with the whiteness.”

48 The cold and violent spring storm darkened the skies of Texas, looming like a false front before a violent thunder burst.

Despite a number of warnings by scouts that the enemy was fast approaching, Travis remained calm and dismissed the reports as exaggerations. Conflicting intelligence passed through Béxar like prairie fires, so that no one knew quite what to believe. There was heightened tension about town, with some of the Tejano population beginning to pack what they could of their belongings. Still, on February 22, 1836, Travis and Bowie agreed to an impromptu celebration of George Washington’s birthday, held at Domingo Bustillo’s establishment on Soledad Street. Barbecues crackled in the cold air, and people roasted beef and feasted on tamales, enchiladas, and strong grain liquor. As the night wore on the guitars and fiddles came out and the volunteers and conscripts danced, even attempting the fandango by whirling smiling Mexican girls awkwardly around the place. Crockett, never one to miss a party, held forth with the ladies, told hunting stories to the men, and dazzled onlookers with jigs on his fiddle for a few songs.

49 Like the earlier fandango held in Crockett’s honor, this one raged on through the night, the mood festive rather than foreboding, the men perhaps sensing that it was the last chance for fun in the foreseeable future.

Neither Crockett nor Travis would have had much time to sleep. By early morning the town was bustling with activity, with the sounds of squeaking oxcarts, of horses neighing, chickens squawking across the busy streets. People were scurrying away from Béxar in droves, scattering with their entire families out into the country. However many of Santa Anna’s forces were coming their way, they wanted no part of them, and would rather take their chances out on the plains.

50 When Travis finally roused and noted the exodus, he detained a few Tejanos for questioning, and when none offered anything of use, explaining deceptively that they were merely getting a head start on their spring planting.

51 Frustrated, and sensing that all these frightened-looking Tejanos knew something that he did not, Travis appealed to a trusted local merchant named Nathaniel Lewis, who reluctantly gave him the grim news: just five miles southwest of Béxar, at Leon Creek, the Mexican army had been sighted, and they were on the move.

52 Sometime in the night the Tejanos had received the intelligence, and they’d been streaming out of town ever since.

In fact, Santa Anna had intended to mount a surprise attack during the fandango, but the storm, snows, and heavy rains had swollen the rivers, thwarting his chances for smooth, efficient crossings. He would have to wait for more cooperative weather, even a full moon.

Travis wanted confirmation of the news, so he positioned a man in the belfry of the San Fernando Church to keep lookout toward the southwest. At mid-afternoon, there sounded the desperate clanging bell from the San Fernando watchtower. Travis and some others hurried to the tower, barely able to hear the watchman shouting “the enemy are in view!” over the din of the bell and their own labored breathing.

53 Travis himself scrambled to the lookout, and he anxiously gazed across the horizon, but there was nothing. No men, no horses, no movement. It must surely have been a false alarm. The sentinel swore adamantly that just moments before he had seen hundreds of mounted cavalry, but now they had hidden behind the brushwood.

54 Travis was inclined to believe the sentinel, but wished he had seen them himself. A moment later Dr. Sutherland suggested that he would ride out and confirm the sentinel’s sighting, if he could take along someone knowledgeable of the area; John Smith, a local carpenter known affectionately as “El Colorado,” volunteered for the detail.

55 They would ride out slowly and signal to Travis in this way: a return at anything other than a “slow gait,” would indicate that the sentinel had seen true.

Sutherland and Smith rode easily but attentively south-southwest, likely trotting along the Laredo Road for a mile and a half or so before they ascended the slope cresting the Alazan hills.

56 The wide flat vista afforded them a dreadful sight, and they reined up hard. They had ridden directly into the head of Santa Anna’s advance guard, hundreds of “well-mounted and equipped” cavalry, and some 1,500 troops at the ready.

57 Sutherland and Smith wheeled their horses around, loosed their reins and spurred hard, whipping their animals quickly to a gallop. Driving rains had slicked the hoof-worn road, and Sutherland ’s horse lost footing, skidding and finally crashing down on its side, Sutherland’s leg crushed in the violent roll. Smith returned just as the horse shook itself back up from the ground, and he helped the injured Sutherland as they galloped again toward Béxar.

Their return speed told the grim news, confirming the sentinel’s report, and Travis launched into action, barking orders, evacuating the town and sending everyone inside the walls of the Alamo. Crockett rode out on his own reconnaissance and met Sutherland and Smith near the vacant main plaza, informing them of the orders to take refuge inside the Alamo. Crockett escorted them inside helping Sutherland down from his horse and, grabbing him up under the shoulder, assisted the limping, shaken man into Travis’s office.

58 Travis was frantically scribbling a letter to Judge Andrew Ponton in Gonzales: “The enemy in large force is in sight. We want men and provisions. Send them to us. We have 150 men and are determined to defend the Alamo to the last. Give us assistance.”

59 He scrawled a similar plea to Fannin in Goliad, reiterating his dire needs: “We have removed all our men into the Alamo . . . We have one hundred and forty-six men, who are determined

never to retreat. We have but little provisions, but enough to serve us till you and your men arrive . . .”

60 Travis handed the first missive to Sutherland, who, practically on one leg, agreed to carry the message to Gonzales. He gave a young messenger named Johnson the note for Fannin. Crockett immediately spoke up, offering his services and those of his men. “Colonel, here I am. Assign me a position, and me and my twelve boys will try to defend it.”

61 Sutherland noted, as he readied to leave, that Crockett and his boys were assigned to “the picket wall extending from the end of the barracks, on the south side, to the corner of the Church.”

62 As a sign to his enemy, Travis raised the national tricolor flag, bearing two stars signifying the two states of Coahuila and Texas.

63Sutherland met up with Smith again on his departure, and as they rode they could see Santa Anna’s cavalry and foot soldiers marching directly into the main plaza, storming the town without a single shot of resistance. The sight, and the sheer numbers, would have chilled the men as they headed quickly out of town and onto the open plain. Sutherland would later recall that the pain in his knee was so excruciating that he considered turning back, returning to the Alamo, for fear he would not be able to bear the long ride to Gonzales. But then the single echoing boom of cannon fire drove him onward.

64Travis had witnessed the unnerving spectacle, too, the rumbling hoofbeats entering town, then watched in bitterness as Santa Anna ordered the blood-red flag of “no quarter” hoisted, signaling his intentions to show no mercy, and the promise of death to any man who dared oppose him, where it waved threateningly above the San Fernando church.

65 In defiant response, Travis ordered the single blast from his eighteen-pounder, a dull and exclamatory report. Insulted, Santa Anna lobbed back a brief volley of four grenades aimed into the compound, but none caused damage or casualties. Word traveled that at the same time the four cannons were fired, the faint sound of a bugle had gone up, indicating the desire to meet and talk.

Travis and Bowie discussed their options, at odds over the next move. Travis preferred to wait, to see what Santa Anna would do, while Bowie thought a discussion, a “parley,” was in order.

66 Though feverish and weakening minute by minute with fever, Bowie still had a brash and independent, even rogue, character, acting on his own as he tore a page from a child’s schoolbook and dictated a message to be written in Spanish. He wished to know if in fact a parley had been called for by the Mexicans. Bowie made certain to end the brief message with words of defiance: “God and Texas.” Without consulting Travis, he handed the message to the Alamo’s engineer, Green Jameson, and sent him off bearing a white truce flag. The cannon fire ceased as he emerged from the garrison.

67Santa Anna considered the men in the garrison rebels and foreigners, in violation of Mexican law, and he had no intention of negotiating. He sent Jameson back with a clipped message: “The Mexican army cannot come to terms under any conditions with rebellious foreigners to whom there is no other recourse left, if they wish to save their lives, than to place themselves immediately at the disposal of the Supreme Government from whom alone they may expect clemency after some considerations are taken up. God and Liberty!”

68 Though the response was ripe with interpretive possibilities, Travis figured that at the very least, he and Bowie would be executed if they surrendered, and if they would not be allowed to leave their garrison with standard “honors of war,” such as those that had been afforded Cós when he was allowed to leave Béxar, then there would be no deal.

69Travis decided to dispatch his own emissary, Albert Martin, who rode out and spoke directly with Colonel Almonte, who had been educated in the United States, and spoke fluent English, so would perhaps prove reasonable.

70 Almonte simply replied that he could not presume to speak for the general, and that in fact, Santa Anna had already offered his reply, and his terms, to Bowie. The discussion was over. Travis added that he would soon let them know if he accepted their terms, and if not, he would discharge another single round from his cannon.

71 Travis had no intention of negotiating, and after a brief and animated rallying of the troops, he let fly the cannon shot.

The Mexicans replied immediately with a sustained volley of bombardment, and Travis could do nothing but retreat to his quarters and wait. Bowie did the same, his condition worsening with some combination of pneumonia, malaria, or typhoid, and with the Mexican artillery fire shaking the Alamo walls, he was barely able to rise from his bunk.

The shelling continued the next morning and into the afternoon of the following day, with Travis now in sole command of the garrison. The men did what they could, which was little, other than remain out of harm’s way. Finally, unconvinced that his and Bowie’s appeals to Gonzales and Goliad had been received, or were explicit enough, Travis stole time in his quarters to pen an eloquent and rousing missive addressed to “The People of Texas & All Americans in the World”:

I am besieged, by a thousand or more of the Mexicans under Santa Anna—I have sustained a continual Bombardment & cannonade for 24 hours & have not lost a man.—The enemy has demanded a surrender at discretion, otherwise the garrison are to be put to the sword if the fort is taken—I have answered the demand with a cannon shot, & our flag still waves proudly from the walls—

I shall never surrender or retreat. Then, I call on you in the name of Liberty, patriotism, & everything dear to the American character, to come to our aid, with all dispatch—The enemy is receiving reinforcements daily & will no doubt increase to three or four thousand in four or five days. If this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible & die like a soldier who never forgets what is due to his own honor & that of his country—

Victory or Death.72

Travis understood his predicament, knew the odds were stacked against them, and now all he and the men could do was hope for some manner of reinforcements. Despite imminent defeat, surrender was simply not an option for the headstrong Travis and the proud men. Like it or not, they were committed to the stand, attempting to defend a relatively indefensible structure against staggeringly overwhelming odds. Bowie lay quivering and shaking in his bunk. Hundreds of miles away, Sam Houston sat sharing a peace pipe with Chief Tewulle, their collaborative efforts having produced a treaty with the Cherokees and assuring they would stay out of the Mexican-American skirmish.

73Crockett, peering over the wall and squinting out at the swarms of soldiers amassing around the flaking adobe compound, would have wondered just what in the hell he had signed up for, and whether the bear he was about to grapple with was a sight bigger than he had reckoned.