SIXTEEN

Smoke from a Funeral Pyre

CROCKETT WOULD HAVE RELISHED his detail at the southern wall, firing his long rifle at enemies a great distance away in the manner of a sharpshooter, his legendary marksmanship boosting the mood of the men. Of the 146-odd men inside the compound, nearly forty were sick and weak with dysentery, run down from lack of rations, exposure to the elements, and the abysmal condition of food and water stores. On the morning of February 25, the enemy artillery served as an early reveille, and Travis soon witnessed more than 200 Mexicans crossing the San Antonio and brashly setting up just 100 yards from the southwest corner of the Alamo, right where Crockett stood leveling his weapon.

1 Travis quickly ordered his crack riflemen, including Crockett, to fire on the Mexicans by opening “a heavy discharge of grape and canister on them,”

2 scattering them into confusion and pinning them down in the brushy-roofed huts or

jacales.

The firefight continued through the cold pelting rain of a descending norther, with many of the defender’s shots hitting their mark, Crockett’s sure and experienced blasts among them. The exchange lasted for hours, during which time Travis noted that his riflemen brought down eight or ten of the enemy, who were dragged off under continuous fire.

3 Crockett continued to blaze away, and while reloading, he ran about excitedly, rallying the other riflemen to shoot true. His enthusiasm and valor impressed Travis a great deal, and he later remarked that “The Hon. David Crockett was seen at all points, animating the men to do their duty.”

4 The sniping was exactly Crockett’s brand of sport, and he covered his comrades as the south gate was briefly opened at Travis’s order and two men slipped silently out on horseback to set fire to the dry

jacales that the enemy had been using as cover. The tactic worked, and without the close cover, the frontal assault was forced to retreat, at least for the moment. But the offensive proved to Travis that a full and sustained attack was imminent.

John Sutherland had ridden the seventy miles from Béxar to Goliad through mind-numbing pain, but he knew the situation at the compound and faithfully delivered his message to Colonel Fannin. Fannin, himself in a delicate frame of mind and uncertain of his own abilities to lead, made a quick, definitive decision, leaving 100 men at Goliad to defend what they had dubbed Fort Defiance, and take the other 320 to Béxar.

5 Fannin’s aide-de-camp at Goliad was a man named John Brooks, who wrote of Fannin’s orders and decision, “We will start tonight or tomorrow morning at the dawn of day in order to relieve that gallant little garrison, who have so nobly resolved to sustain themselves until our arrival.”

6 It was a glimmer of hopefulness that the besieged at Béxar would never know about, for the relief effort, while noble and well-intentioned, soon foundered. They were threadbare, near-starved, with scant provisions, and an inauspicious start doomed the mission at the outset. One of the ox-drawn wagons broke a few hundred yards into the journey, and crossing the rain-swollen San Antonio proved tedious and time consuming. The muddy track made the going excruciatingly slow, and several of the oxen managed to wander off in the night.

7 They were a ragged and unprepared army, devoid of winter clothing, their boots rotting off their feet, and almost out of ammunition. Fannin determined that his troops were in no condition to rescue anyone—they needed reinforcements themselves. His heroic rescue mission was dead in the water before it even began.

The beleaguered defenders would continue to wait, to pray for troops to come to their aid. Crockett kept up his daily sharpshooting to pass the time, and some reports suggest that his rifle was the one to bring down the first of the enemy soldiers. Late in the day on February 27, as long, muted light began to whiten the walls of the Alamo, a cocky Santa Anna rode toward the mission at the head of his men, almost as if calling Crockett and his boys out. They were happy to oblige, and a rumor went round that a bullet fired from Crockett ’s rifle sent the arrogant general clambering for cover, the shot nearly killing the famed Napoleon of the West.

8In the early morning hours of March 1, in the cold blackness on the other side of midnight, the hopes of the defenders were answered, if only in a small way. Thirty-two brave men of Gonzales had responded to Travis’s dramatic plea and ridden the dangerous road. They arrived at the gates of the Alamo under cover of darkness, wet and cold, their hands frozen to their reins, and after some confusion—the defenders could not be certain they were friendly and even fired on them once—they were hurried inside the walls and welcomed.

9 Though small in number and unlikely to significantly shift the balance of power, the fact that they had been able to ride through enemy lines and sneak inside the fort proved uplifting to Travis and his men, who now believed that more might be en route.

But the arrival of the “Gonzales Ranging Company of Mounted Volunteers,” led by “El Colorado” John Smith himself, had been more lucky than skillful. Santa Anna had anticipated Fannin’s relief to arrive from the southeast, heading up from La Bahia, and had stationed patrols there. Coming from the northeast, Smith and the volunteers rode right in.

10 Still, the reinforcements lifted spirits inside the garrison, and though the day dawned freezing cold, men scurried about with a renewed cheer-fulness.

Crockett took out his fiddle for a jig or two, joined by the Scotsman John McGregor, and the two of them played tunes together, a huddle of men humming along, clapping and laughing when the two competed to see who could create the most noise with his instrument.

11 Crockett ’s grin, good humor, and storytelling buoyed the cold, hungry, and lonely men during the long days under siege by an army whose numbers grew to frightening proportions. Travis, feeling spry with the arrivals, ordered his gunners to launch two cannonballs from his twelve-pounders, one crashing into the military plaza, the other exploding on its target in a direct hit, tearing through the timber roof of a house suspected to be the headquarters of Santa Anna himself and sending Mexicans scattering for cover.

12Travis and the men were unaware of most of the goings-on outside their immediate surroundings. It was probably best that Travis was ignorant of Sam Houston’s behavior and state of mind, for the notorious Raven was in Washington-on-the-Brazos at the constitutional convention, where, rather than acting like a general and future president of Texas, he was engaged in a raging drunk. His drinking was so severe that his friends had to physically subdue him and carry him from the grog-shops to his bed. When, on March 2, the

Brazoria Texas Republican published Travis’s “Victory or Death” letter, Houston balked, doubting the veracity of the letter and calling it “a damned lie,” then adding that the reports by both Travis and Fannin were schemes to bolster their popularity.

13 The resulting doubt about the claims from Béxar slowed immediate action from Washington-on-the-Brazos.

Meanwhile, on March 2, Santa Anna resumed his shelling of the compound, and even began slowly inching his artillery forward, pinching in closer and closer to the Alamo walls.

14 Beneath his veneer of hope and optimism, Travis would have been feeling exasperated frustration, noting that his appeals had gone mostly unanswered, and that thirty-two men was hardly enough. He had expected Fannin and hundreds.

The next day Travis witnessed a harrowing sight: long, serpentine lines of enemy soldiers streamed into Béxar, numbering over a thousand strong by the looks of them. Even more disconcerting, the arrival of this regiment, a well-armed cavalry in full-dress regalia, was heralded by music, boisterous singing, drums, firing weapons, and fanfare, so that he concluded (wrongly, it turned out, since Santa Anna had actually been there since the siege began) that the hoopla signaled the arrival of Santa Anna himself. As he stared grimly across the river and the plaza, Travis surveyed a force of some 2,500 troops.

15But Travis also witnessed something else, something nearly miraculous considering it was broad daylight: James Butler Bonham galloped up, having managed to squirt directly between the Mexican-seized powder house and cavalry commander General Ramirez y Sesma’s troops. It was a daring move: after hiding in the thicket and brush, he had bolted for open ground and spurred hard, swinging low on his mount to minimize himself as a target, but no fire came. At around 11 a.m. Bonham arrived inside the Alamo walls.

16 He quickly reached into his saddlebags and produced a letter from R. M. Williamson in San Felipe, addressed to William Barrett Travis, dated March 1, 1836. The words could not have been more welcomed, suggesting that even as Bonham read, Texians were hastening to their defense. It was precisely the kind of positive news the garrison had long awaited:

Sixty men have set out from this municipality and in all human probability they are with you at this date. Colonel Fannin, with three hundred men and four pieces of artillery, has been on the march toward Bejar for three days. Tonight we expect some three hundred reinforcements . . . and no time will be wasted in seeking their help for you . . . PS. For God’s sake, hold out until we can help you.

17

Travis took Bonham’s unscathed arrival as a prompt that he might also succeed in getting a messenger out, and he retired to his quarters to write the convention in Washington. He would choose his words and tone carefully, resulting in a most detailed, informative, and patriotic document, one that reiterated his intention to fight to the death, reinforcements or none. He coldly and clearly assessed his military situation and laid out his military needs. “Colonel Fannin is said to be on the march to this place,” he wrote, adding his dubious appraisal, “but I fear it is not true.” He reiterated that despite incessant shelling since February 25, they had managed to hold the fort down without losing a single man. Travis told the men of the convention that he was completely surrounded by the enemy, yet despite the continual bombardment, he had been able to fortify “this place, that the walls are generally proof against canon balls.” He then turned to the condition and mental state of his brave defenders. “The spirits of my men are still high, though they have had much to depress them.” He went on to estimate that the enemy encircling him was between 1,500 and 6,000, including the thousand marching in as he wrote.

18He needed help, and he needed it now. He carefully outlined his desires: 500 pounds of cannon powder, 200 rounds of cannonballs in six-, nine-, twelve-, and eighteen-pound balls, ten kegs of rifle powder, and a healthy supply of lead, all sent with no further delay, under heavy guard.

19 If these requests were quickly met, he and the defenders might just have a chance. But if the relief did not arrive expeditiously, Travis would have no alternative but to “fight the enemy on his own terms,” and those terms were to the death, with a “no prisoners” provision from the enemy. “A blood-red banner waves from the church of Bejar, and in the camp above us, in token that the war is one of vengeance against rebels. They have declared us as such, and demanded that we should surrender at discretion, or that this garrison should be put to the sword.”

Travis closed with defiance, pointing out that the red flags of “no quarter” did not faze him, nor his men. “Their threats have had no influence on me, or my men, but to make all fight with desperation, and that high souled courage which characterizes the patriot, who is willing to die in defence of his country’s liberty and his own honor.”

20 In a cryptic and grim postscript, Travis underscored that the enemy reinforcements continued to pour in, and their numbers would soon mount to two or three thousand. He signed off—“God and Texas—Victory or Death.” He pressed the long letter into his courier’s hand and sent him toward Washington, where the delegates were busy framing the Texian Declaration of Independence, lifting most of it directly from that of the United States of 1776.

Perhaps sensing that the end was drawing near, Travis penned two more letters during the day, these shorter and more personal, one to his friend Jesse Grimes, the other a brief note to friend David Ayers, guardian of Travis’s son. Perhaps fearing that his first letter would fail to make it through the enemy lines, Travis reiterated some of that correspondence, then added

Let the Convention go on and make a declaration of independence; and we will then understand and the world will understand what we are fighting for. If independence is not declared, I shall lay down my arms and so will the men under my command. But under the flag of independence, we are ready to peril our lives a hundred times a day, and to dare the monster who is fighting us under a blood-red flag, threatening to make Texas a waste desert . . . If my countrymen do not rally to my relief, I am determined to perish in the defence of this place, and my bones shall reproach my country for her neglect.

21

He had made his case, politically and militarily, so that now all that was left was to write a note regarding his son, which echoes some of the sentiment found in Crockett’s letter to his family back in January. Both mention that securing Texas would result in a “fortune” for themselves and their families. Travis procured a ripped scrap of yellowing paper and scribbled the following:

Take care of my little boy. If the country should be saved I may make him a splendid fortune. But if the country should be lost, and I should perish, he will have nothing but the proud recollection that he is the son of a man who died for his country.

22

Thinking of his son and certainly doubtful that he would ever see the boy again, Travis handed the letters to his trusted envoy, “El Colorado” John Smith, and sent him on his way.

Ironically, the same day, March 3, in Washington-on-the-Brazos, the declaration of independence was read aloud to the assembly and signed by everyone present, officially ratifying the Republic of Texas.

23 The next day, Sam Houston was made commander in chief of the army, and it would be his job to rescue the defenders if he could gather enough troops and get there in time.

The next morning, Santa Anna began bombarding the fort and he kept the pressure on throughout the day, pointing the bulk of his efforts on the north wall. Dismally low on powder, Travis could do no more than shrug and hold off with any retaliation, which would be token at best. He would need all ammunition and powder for the major assault, which he must have sensed looming. The only shots Travis is said to have fired that day or the next were three signal shots, aimed at any aid en route, denoting that he was still holding down the fort.

24 A few days earlier, Bowie had felt good enough to be lifted on his cot and brought out into the open air of the courtyard, and had even encouraged some of the men to stand strong and proud. But by now he was back in his quarters, his ailments gripping him to the core, clutching him in feverish shakes.

David Crockett may have been thinking of the hunting grounds he had discovered on the Red River, or favorite old haunts back home, as he looked out at the overwhelming odds they were about to face. He had done what he could to shore up the morale of the men, playing music, telling jokes and tall tales, but even his optimism would have been tested by the spectacle of being surrounded by thousands of men, the constant strain of watching the horizon and hoping for recruits to arrive. Crockett wished to be out on the open plain again, and a claustrophobic feeling overtook him as he pondered the walls of the fort now penning them in like cattle herded to slaughter. “I think we had better march out and die in the open air,” he said aloud. “I don’t like to be hemmed up.”

25 But it was only the wishful thinking of a man who longed for the freedom of open country once more, who dreamed of outriding, perhaps conjuring that idyllic Honey Grove, the twice-yearly passing of buffalo, the sweet smell of blossoms and hives dripping with honey.

Santa Anna convened a war council on the eve of March 4. A few of his officers suggested that, if the general were willing to wait for even more artillery to arrive, then the Alamo could be taken with very little loss of Mexican troops.

26 But the tactical Santa Anna craved drama, and more than that, he wished to send a message to both the rebellious “pirates” and his own troops. Attacking now, in great force, “would infuse our soldiers with that enthusiasm of the first triumph that would make them superior in the future to those of the enemy.”

27 He had already said that the attack would serve as a necessary example to Béxar and all of Texas, of the price of rebellion, “in order that those adventurers may be duly warned, and the nation be delivered . . .”

28 His mind was made up, and when the topic of how to treat prisoners of war was broached, Santa Anna scoffed and waved his officers away. His army would take no prisoners.

29On March 5, the observant hunter Crockett would have noticed that the Mexican camp, its troops and guns, was eerily silent, the menacing electric tension of a calm before a storm. The crumbling fortress had endured twelve consecutive days of near-constant shelling, and Crockett and the rest of the men would have welcomed the respite, a chance for the ringing in their ears to cease. The quiet would give them a chance to think about their families, their goals and dreams for the future, the many trails that had led them here, and, for those who believed, what the afterlife might bring. And the tranquil air would give some of them a chance to sleep, especially those who had been trading watch for nearly two weeks, their eyes burning with sleep deprivation. Travis would send out one last messenger, a youngster named James Allen, with a last-ditch appeal to Fannin to come fast.

30 Travis then made the rounds of the garrison, posting sentries outside the walls and on guard, and then ascertaining that all the men on watch had multiple “loaded rifles, muskets or pistols,” at their immediate reach.

31 Finally, convinced he had done all he could up to now and certainly for today, Travis slumped into bed sometime after midnight.

About the time Travis was being overtaken by exhaustion, Santa Anna and his officers began rousting his men with severe whispers, poking them with staffs or kicking them awake with boots, fingers pressed to their lips, ordering complete silence for the dawn attack.

32 Crowbars and ladders were distributed, and officers made certain that all men in the attack wore shoes or sandals for ascending the walls, to assure they did not give away their positions by yelping out in agony as their bare feet met sharp rocks and thorns or prickly cactus.

33 On his command, which would be given at 5 a.m. March 6, the men were to assault in linear formation, and those in the first waves would have known they would be cut to pieces by musket fire and cannonballs tearing dreadfully at the columns of men.

34 Resolute and following orders of their supreme commander, the men shook from sleep and formed lengthy columns, their sharpened bayonets gleaming in the moonlight. Simultaneously, Sesma saddled his cavalry, their job to survey the perimeter of the Alamo and make certain that no one escaped the attack once it was under way. Though the temperatures had warmed slightly the day before, it was still cold, and the horses and men huffed cottony plumes of breath that mingled with the shimmering moonglow. The men stood shivering, holding weapons or tools, their long moon shadows ghoulish, waiting for the command to move. By 3 a.m. they stood like zombies, waiting for orders in the snap-still air. At 5:30, Santa Anna ordered Jose Maria Gonzalez to sound the call to arms, a sound inspiring the men to “scorn life and welcome death.” Other trumpeters picked up “that terrible bugle call of death,” and the columns began the assault.

35Travis’s sentries, exhausted from weeks at their posts, stood or sat dozing, leaning uncomfortably against walls or their muskets. None detected Santa Anna’s stealthy death march, the sound of hundreds of horse hooves, or their whinnies and exhalations, the metronomic clank of metal and arms, the panicked voices of frightened foot soldiers reciting their last prayers, until it was too late. Long skeins of light tore across the embattled sky as night fought to become day, the weird moonlight lingering on the plain, bathing the fort in a surreal glow. Santa Anna’s men were upon the Alamo.

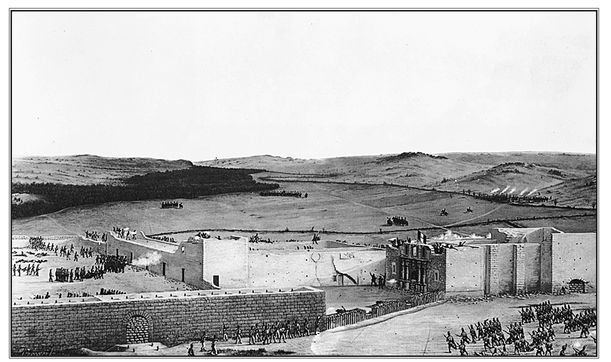

March 6, 1836, Santa Anna’s army storms the Alamo. (FALL OF THE ALAMO. Theodore Gentilz. Gentilz-Fretelliere Family Papers, Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library, San Antonio.)

The attackers responded to the bugles and surged forward, shouting “Viva Santa Anna” and “Viva Mexico,” and then, spurred by blood lust and their own code of honor, they also began to chant

“Muerte [death]

a los Americanos!!”36Officer John J. Baugh finally woke to the commotion and sprinted to Travis’s quarters, hollering “The Mexicans are coming!” Travis instinctively clutched saber and shotgun and dashed for the north wall, his slave Joe at his heels as he reached the gun emplacement amid the horrible and confused flashes of enemy gunfire from without and the lowing and baying of terrified horses and cattle from within.

37 Inside, the Alamo awakened to the nightmare; half-dressed men streaked from their cots in the long barracks and scrambled to positions, shooting rifles randomly, igniting cannons and aiming them vaguely at the gray-black lines of men they could make out in the half-dark. The blazing, orange-yellow arcs of cannons whistled and spit skyward, then died out in the distance as the ordnances fell to the ground. Travis climbed quickly to the emplacement and looked down, seeing soldiers leaning ladders against the walls. He turned back to his men in the fort and shouted,

“Come on, Boys, the Mexicans are upon us and we’ll give them Hell!”For a few minutes, they did. Without proper canister shot, Travis had made do, ordering the men to stuff their shotguns with “chopped up horseshoes, links of chain, nails, bits of door hinges—every piece of jagged scrap metal they could scavenge,” firing these deadly shotgun blasts on the huddled masses of men below.

38 A violent hail of fiery shards sliced down on the columnar waves of charging Mexicans, cutting many to pieces in their tracks. Travis peered over the wall at the surging onslaught, shouting encouragement and ordering another volley of shotgun blasts and a first surge of round shot in the form of nine-pound iron, when his head snapped back, a leaden ball from a Mexican Brown Bess striking him in the forehead and hurling him backward into a motionless heap against one of his own cannons, his gun still clasped in his hands.

39Crockett was somewhere in the frenzied rush to defend, amidst the cacophony of cries from comrades taking lead balls from volleys thrown by the onrushing waves of the enemy. The inside of the fort flickered, illuminated by gunfire and cannon flare. He would have fought for all he was worth, galvanizing his knowledge of warfare and defense into one last-ditch effort to survive. Crockett no doubt clambered to a post and started shooting, helping expel the initial surge which fell back, taking heavy casualties, but then resurged. Mexican sergeants and officers flogged any recruits trying to retreat, herding new formations on ahead.

40 With a second formation hammering hard at the north wall, forces also pinched like talons from the south and the east, while Santa Anna’s reserves, and his band, lay in wait by the northern battery.

41 Desperate columns, taking incessant grapeshot and ducking under the dreadful whir and whistle of flaming metal flying overhead, convened near the north wall. Crockett and his riflemen fired and reloaded as fast as they could work, grabbing rifle after rifle until all their pieces were empty and they were forced to stop and reload once more, their efforts forcing the oncoming column to angle out and away, toward the southwest corner.

42A third advance came, and now the Mexicans were mounting the ladders, redoubling their efforts. Two other ragged lines at the east and northwest had breached and reformed, and now all merged into a single swarming mass at the base of the north wall. They were too close for cannon fire, but shotgun spray and rifle bullets peppered them from above. Still, they came, now scaling the rough woodwork repairs that latticed the outer walls. They placed ladders, and into the face of direct fire, up and over they went, droves upon droves of men hoisting each other from the bottom, climbing over one another, stepping on each other’s arms and hands and heads. Soon, the defenders at the top could no longer reload fast enough to repel the sheer numbers mounting the parapet, and they found themselves engaged in hand-to-hand combat, stabbing viciously with bayonets and knives. José Enrique de la Pena was there under Santa Anna’s command, and he remembered the scene vividly:

The sharp reports of the rifles, the whistling of bullets, the groans of the wounded, the cursing of the men, the sighs and anguished cries of the dying . . . the noise of the instruments of war, and the insubordinate shouts of the attackers, who climbed vigorously, bewildered all . . . The shouting of those being attacked was no less loud and from the beginning had pierced our ears with desperate, terrible cries of alarm in a language we did not understand.

43

The Alamo had been breached.

As the north wall fell and the Texians retreated under the onslaught, the fight turned inward, with defenders shooting anything that resembled a Mexican uniform, brandishing tomahawks and long knives, hacking and stabbing wildly with bayonets. Mexicans poured over the south wall as defenders retreated to the open courtyard, while some, hemmed in on two sides now and staring down certain death, leapt from their positions on the palisade or squirted through the corner of the cattle pen.

44 Those who managed to escape were summarily ridden down and slain point-blank in the ditches and chaparral surrounding the fort by Ramirez y Sesma’s men, who killed them with lances.

45 Crockett ’s desire to die out in the open air may have crossed his mind, but he had his hands full fending off the newly breached south wall and the hundreds of Mexicans streaming in. Now soldiers outside used massive timber to bash and ramrod the gates, also breaking through any and all windows and doors. Crockett and his riflemen stood in defiance as long as they could, “then withdrew into the chapel.”

46The Mexicans moved room to room, blasting doors apart with the defenders’ own cannons, entering with bayonets brandished. Reaching the hospital rooms they found the sickly, weak, and debilitated men feebly attempting to defend themselves, the once-strong and fierce knife fighter Jim Bowie among them. He lay in his cot, beneath the covers, perhaps already unconscious, and he offered no resistance as the Mexicans stabbed him repeatedly, then fired on him at point-blank range, spattering his brains across the wall.

47By now there remained only a handful of defenders still alive inside the Alamo walls, and the Mexicans had but to round them up and slaughter them one at a time. The chapel held the last defenders. The Mexicans blew the chapel open with cannon fire and pressed in, enveloping a small knot of six men who were now surrounded. David Crockett was among the last standing.

48Santa Anna received news that the Alamo was secured, and soon he entered, scanning the dreadful slaughter in the first pink-orange embers of daylight. Perhaps forgetting the previous chant of

Degüello, no quarter and no mercy, General Manuel Fernandez Castrillion brought forward Crockett and the others, whom he had ordered his reluctant soldiers to spare. Santa Anna took no time at all to scoff at Castrillion, waving him away “with a gesture of indignation,” and order the immediate execution of David Crockett and those who stood with him that cold morning. Nothing happened for a moment, and it appeared that the men might actually disobey their commander. They had seen enough killing, and these helpless men now posed no immediate threat. But in the dim twilight, the sky and air gunmetal cold, officers hoping to ingratiate themselves with their leader leapt forward, “and with swords in hand, fell upon these unfortunate, defenseless men just as a tiger leaps upon his prey. Though tortured before they were killed, these unfortunates died without complaining and without humiliating themselves before their torturers.”

49David Crockett was dead.

BY THE TIME all the smoke had cleared and the bodies were counted, Santa Anna’s one-sided victory proved to have come at a very high cost—nearly 600 of his men had been wounded or killed. Commander in Chief Sam Houston marched toward the Alamo, realizing that the pleas from the fort had been legitimate, but by now of course it was too late. Houston took his own sweet time moving south, spending five entire days on a ride that should have taken just two, during which time he camped two nights on the Colorado.

50 On March 11, Fannin received two missives from Houston, the first confirming that the Alamo had fallen, the second ordering Fannin to withdraw, repositioning for defense at Victoria, on the Guadalupe.

51 He was also instructed to blow up the fortress before departing.

Fannin dallied, and his indolence cost him and his men dearly. Mexican General José de Urrea closed in quickly, catching Fannin in retreat on March 18 and surrounding him a day later out on the open plain. By the end of a daylong skirmish Fannin had suffered sixty losses compared to 200 Mexicans, but by the next morning Urrea received significant reinforcements, rendering Fannin and his men defenseless. When Urrea, a humane and decent general, called a ceasefire, Fannin believed he might convince his opponent to offer reasonable terms of surrender, but he had not reckoned on the wrath of Santa Anna, who reiterated his order that rebels and traitors be executed on the spot.

52 Urrea hated to do it, but after seizing all of Fannin’s weapons and ammunition, the sickened Mexican general marched Fannin and his men in four columns out onto the road under the guise of wood-gathering and a journey to Matamoros, and summarily leveled them with musket fire, finishing them off with bayonets and knives until 342 men were slain. A few dozen escaped to report the horrific event.

53On April 21, 1836, Houston finally entered the fray, advancing on Santa Anna’s fatigued army which, with two recent decisive victories and blood still drying on their hands, understood Houston to be in full retreat mode. Instead, Houston marched two parallel but roughshod columns totaling some 900 men inflamed by the battle cries “Remember the Alamo!” and “Remember Goliad!” The surprise attack stunned Santa Anna and his exhausted troops, who were unprepared to defend themselves in soldierly fashion, and lapsed into panic and confusion.

54 Even Santa Anna himself—who had been sleeping—became disoriented, unable to give useful orders as the Texians advanced in battle frenzy. They continued to chant “Remember the Alamo, remember Goliad”; some were even said to cry out “Remember Crockett!” The attack was so sudden and unexpected that many of the Mexicans simply ran for their lives, but were thwarted by the bayou and the lines of Texians, who gunned them down.

55The Battle of San Jacinto was really more of a slaughter, a revenge massacre for Santa Anna’s “no quarter” victories at the Alamo and Goliad. Men were shot attempting to swim away in the Buffalo Bayou, others ridden down and impaled with bayonets, and many were shot point-blank in the head. One Texian participant called it “the most awful slaughter”

56 he ever witnessed. It was over in just eighteen minutes. Houston had two horses shot from under him and his ankle shattered by a rifle ball, yet he could take solace in the fact that he’d captured the Napoleon of the West, when Santa Anna was finally rounded up and taken prisoner. Shrewdly realizing that the great general was more useful alive than dead, Houston would hold on to his prize until he could get what he wanted, which was the rest of Santa Anna’s army back in Mexico, on the other side of the Rio Grande.

57 As a result of his success at San Jacinto, Sam Houston joined his old friend from Tennessee, David Crockett, as a hero of Texian independence. Houston would live to be elected twice as the president of the new Republic of Texas and ultimately governor of the state—Crockett would live on as a legend.

58Back home in Tennessee, it did not take long for the rumors of Crockett’s demise to arrive. In mid-April the

Niles Register, quoting from the

New Orleans True American, listed Crockett as having fallen with the fort: “Colonel David Crockett, his companion Jesse Benton, and Colonel Bonham of South Carolina, were among the number slain.”

59 Elizabeth would certainly not have been surprised: he had nearly died afield more than once, had tricked death time and again—she well knew the Christmas gunpowder story, the barrel-staves scrape, all the close calls. The stalwart, now twice-widowed woman knew how to keep scrapping when things got tough, and she would certainly have lowered her head and pressed forward. By early summer, tender and heartfelt letters of condolence began to find their way to her, canonizing the man she knew as well as anyone had—and knew as a man, not a legend. She had known his love for the outdoors, known him to be happiest when in nature, and she would have been especially moved by the letter she received from Isaac Jones of Lost Prairie, Arkansas, the man to whom Crockett had sold his watch, who returned the timepiece out of respect. Jones offered his sympathies, adding that with Crockett’s loss, “freedom has been deprived of one of her bravest sons . . . To bemoan his fate, is to pay tribute of greatful respect to nature—he seemed to be her son.”

60Although Crockett failed to garner the coveted “league of land” or fortune for his family, Elizabeth was eventually granted his soldier’s share, and in 1854 she and a handful of family members and children followed his tracks from Tennessee to Texas, where they would live out their lives, and Crockett ’s dream, on the vast frontier.

61 Robert Patton Crockett, eldest son by Elizabeth, went earlier, heading to Texas in 1838 to volunteer his services in the army as his father had done. Elizabeth remained true to the memory of her husband, and was said to wear black until her own death, in 1860.

62John Wesley Crockett followed his father’s trail to the United States Congress, where he served two consecutive terms beginning in 1837, winning the seat left open by the retired Adam Huntsman. John Wesley Crockett picked up where his obstinate father had left off, and, fittingly and ironically, in February of 1841, John Wesley drove through the passage of a land bill in many ways comparable to that which his father and Polk had compromised on back in 1829.

63 Apparently content with that punctuation mark on his father’s congressional career, John Wesley opted to retire at the end of his term in 1843.

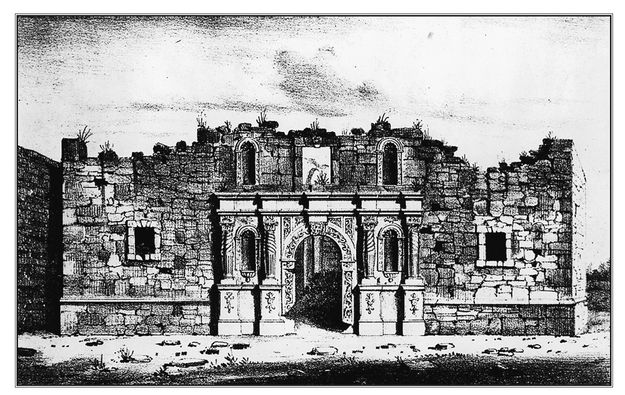

Ruins of the Church of the Alamo, San Antonio de Bexar. (Lithograph by C. B. Graham, after a drawing by Edward Everett. In government report by George W. Hughes, 1846, published as Senate Executive Document 32, 31st Congress. Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library, San Antonio.)

SANTA ANNA WOULD FINALLY SAY of the storming and subduing of the Alamo, which took just a single hour, “it was but a small affair.” He perused the carnage, hundreds of bodies strewn and smoldering, their “blackened and bloody faces disfigured by desperate death.”

64 After briefly praising his troops for their courage, he ordered the dead defenders piled into three heaps, two smallish mounds outside the grounds, and one large central pyre for those slain within the Alamo walls.

65 Soldiers then scoured the countryside to collect dry wood, lugging it back in carts. With sufficient wood gathered, soldiers mounded men and wood in piles, scattered smaller pieces of kindling about, doused the mass with flammable fluids, and pyre by pyre, set the Alamo defenders ablaze. The flames rose high and the fires burned all through the day and then into night, spitting and smoldering for three full days, until vultures began circling over the mission and crowds gathered around the ashes and embers.

66 Fragments of bones and the curling remnants of charred flesh lay among the ashes, and “grease that had exuded from the bodies saturated the earth for several feet beyond the ashes and smoldering mesquite faggots.”

67Somewhere high above, David Crockett’s spirit drifted freely on the Texas wind, lofted away to immortality by the smoke of his funeral pyre.