The Bigger They Come

My friends know me as a man who likes to exaggerate, but for the next five thousand words I’ll stick to a sober recitation of the facts, the better to deal with events that are themselves sufficiently exaggerated. What I’m referring to are the two most extraordinary fish of my angling career, the first extraordinary for the circumstances of its capture, the second, for the circumstances of its capture and the extraordinariness of its size.

There are two schools of thought on catching big fish. One school holds that you fish for them deliberately, use outsize lures and streamers, fish only those lies capable of sheltering fish of weight. The second maintains the best way to catch big fish is to work your way through as many lesser fish as possible, harness the laws of probability to your cause. This last may be called the lottery school of fly-fishing, and it’s the one to which I belong, since it pretty well matches what I’ve learned of life. The big things come unexpectedly amid the ordinariness of daily routine, and to deliberately go hunting Joy or Love with a metaphoric net would be to doom yourself to failure by the very nature of the quest. No, I’m a small-fish fisher, a small-fate man, who hopes, like we all do, for miraculous things.

But this by way of preface. From here on in I’ll adhere to the Joe Friday school of angling literature: the facts, ma’am, just the facts.

It wasn’t meant to be a fishing trip at all. Nova Scotia for two weeks—a trip we could manage with our baby. That I packed a small fly rod was of no significance; it goes into my duffle bag the automatic way my razor does; it wouldn’t matter if my destination were Bahrain. That Nova Scotia has some fine fishing is something I was aware of, of course, but that only added a vaguely illicit interest I wasn’t going to allow myself to pursue.

Nova Scotia is not your undiscovered, off-the-beaten-track gem, but it’s still lovely for all that; the descriptions that speak of it as “Vermont surrounded by ocean,” or “New England thirty years ago,” are both true. With its mix of Acadian, Loyalist, and Scots traditions, its coastline that out-craggys Maine’s, and its laid-back Canadian citizenry, it’s the perfect spot for the kind of relaxed family vacation we were after. Starting in Halifax, we were going to travel around toward Cape Breton, staying at bed and breakfasts, driving in the morning, hiking and picnicking in the afternoon.

Our first night was spent near the Saint Marys, a famous salmon river, but only because it’s where we happened to be when evening caught up to us. And though I may have briefly entertained the notion of trying a cast or two, the south-coast rivers were already closed for the season, the victims of a summer-long drought that was the worst on record. Still, after we settled in, there was no reason not to stroll over to the river and have a look-see; our landlady told us about a bald eagle who made his home in a spruce above the iron bridge, and we wanted to try and spot him.

The facts—and yet already a digression. My attitude toward salmon, to this point in my life, could pretty well be summed up by the term reverse snobbery. Yes, I knew about the mystique—about how Atlantic salmon were the king of game fish, strong, brave, beautiful, and scarce; of Lord Grey of Falloden and Edward Ringwood Hewitt and Lee Wulff and Ted Williams, and all the famous flyfishers who dedicated their lives to its pursuit. And yes, I knew about the efforts of conservationists not only to preserve the salmon in their present range, but to bring them back to the New England rivers they once inhabited. I even, God forgive me!, knew what it was to carve into a side of smoked salmon, curl off a piece, and drop it on rye bread with a whisper of onion, wash it down with good Danish beer. I knew all these things, which isn’t bad for a man who hadn’t, until this moment, seen an Atlantic salmon that was actually alive.

The reverse snobbery? Well, weren’t all salmon fishers rich bastards who mouthed pieties about protecting the fish (protecting them, that is, from fishermen whose bank accounts weren’t as large as theirs), while back at work they were presidents of corporations that were despoiling the environment as fast as possible? And even the local effort to return salmon to New England rivers—wasn’t that a misuse of scarce conservation dollars, trying to bring something so fragile back to a region where fish and game laws still reflected the ethos of the eighteenth century? Just before our trip a man had been arrested for catching and killing one of the first Atlantic salmon to make it all the way up to the White River in Vermont; the man had been previously charged with beating his wife, and was to shoot himself before he could be brought to trial for killing the salmon. In a bizarre kind of way it all fit in—the violence done the salmon, the violence done to man. No mystique for me, thank you—when it came to my attitude toward salmon, I was very skeptical and confused.

At least until that walk along the Saint Marys. We found the eagle fast enough—he was soaring in a spiral from bank to bank, with the majestic, disdainful quality all eagles possess. We stood on the bridge trying to get our daughter to share in the excitement—“See, Erin? See nice pretty eagley?”—when fifty yards upstream there was a splashing sound with an odd uplift to it, as if someone were throwing rocks out of the water. I forgot about the eagle, and shifted my focus to a lower plain. There it was again, and this time there was no mistaking the fluid, bright shape that appeared a second before the splashing sound and disappeared a second before its echo.

Salmon! In the drought-ravaged river, they were in the one pool big enough to shelter them, and seemed—when we balanced our way along the bank to it—not overly concerned by their plight. The water was deep and dark enough that it was hard to make them out, at least until they jumped. They went straight up in the air then, and it was so sudden and joyous our hearts lifted with them, so we laughed out loud at their sheer exuberance. There were no falls there, no dams—if anything, they seemed to be jumping out of the depths of their contentment, as if remembering in intervals they were salmon and were expected to do so for our delight.

By the time it was too dark to watch any longer, I was, if not converted to the mystique, at least firmly in the salmon’s corner as a devoted fan. Unlike other big fish I’d seen, I was not immediately possessed by the desire to be attached to one; it was subtler, more a wanting to be around them, the way people swim with dolphins.

Next morning we stopped briefly to see if the salmon were still there; if they were, they weren’t jumping, and we contented ourselves with another good look at the eagle. Later in the morning was the restored village of Sherbrooke, then beautiful, lonely Wine Cove, and then our trip was fully in gear, and we made our way in a back-and-forth looping toward Cape Breton and the dramatic headlands of that coast.

The weather, with the drought, was gloriously sunny and hot. Here on the watersheds flowing into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence the salmon season was still open, though the rivers looked just as low and hopeless as they had in the south. I thought about fishing, went so far as purchasing a license, but between my flimsy trout rod, a few battered trout flies, and a wife and child, it seemed better to concentrate on the hiking and beachcombing we could all do together.

And then I got my chance—at some brook trout fishing. We were passing the Cheticamp River, a beautifully clear stream flowing seaward from some bread-loaf-shaped hills a short way above the Acadian town of the same name. It was a hot Sunday afternoon, half of Cape Breton seemed to be out enjoying the sunshine, and we had already stopped in a roadside store for the makings of a picnic. Leaving our car at the campground, we slipped Erin into the backpack, then started through the dappled sunlight of the old woods road that parallels the river’s bank.

The first salmon pool is a forty-minute walk in from the road, and this is where we decided to stop—not because of the salmon (the river was too low to think about that) but because the granite ledge that shelved down into the pool was a perfect spot for a picnic. While things were readied, I waded down below the pool to the only fast water in sight. I was wading wet—in that heat, it was the only comfort available—and I had nothing stronger than my featherweight pack rod—perfect for seeking out the small brook trout I hoped to find.

Small fish, small fly. I was tying on a number-fourteen Royal Wulff when behind me in the pool was a tremendous splash, as if someone had just dove headfirst off the ledge. I spun around, startled, and was just in time to see my wife pointing down toward the pool with what can only be described as an expression of total dumbstruck awe. Any doubt about what had caused the sound disappeared instantly—again, there was a tremendous splash, only this time at the center of it, breaking the pool’s surface, becoming detached from it, hanging there like the froth of a silver geyser, hanging there for what seemed like minutes, hanging . . . hanging . . . tilting . . . falling . . . knifing back in, was a . . .

“Salmon!” we yelled, simultaneously.

The salmon was jumping, not rolling—I was told later a jumping salmon will never take a fly. But I was too inexperienced to know this; my hands shaking, I finished tying on the fly, added two more half hitches, then waded the six or seven steps to the lip of the pool. The salmon had come up seventy feet away—a heroic cast for a little rod—but I was afraid coming any closer would frighten him off. I worked out line as quickly as I could, then—David with a slingshot—let the fly shoot forward in what was undoubtedly the longest, luckiest cast of my life.

The fly landed perfectly, its tail pert on the water, its hackles puffed and upright. There was barely any current in the pool, so it floated back toward me slowly, my emotions traveling with it in the classic emotional pattern of a drift—anticipation and alertness flowing imperceptibly toward disappointment as the fly came back untouched. Not on this cast, I decided, but just as the thought formed there was a saucer-sized dip in the water below the fly, then something yearning up toward it, and faster than my thoughts could operate, my rod arm was high above me and with an amazing, exhilarating tightening—a tightening with a bottom to it—the salmon was on.

I reacted very coolly to this: I shouted “Holy fuck!” and immediately fell down.

But even reduced to a state of blithering idiocy, there was a surer instinct at work, and the tight arc in the rod never softened, even as I thrashed my way to my feet. The fight that ensued lasted nearly a half hour, and while there wasn’t a moment during that time I wasn’t terrified the salmon would break off, I also knew, in the strange contradiction only fishermen will understand, that I had him, and unless I blundered badly the fish was mine.

For even with that toy rod, the odds were all in my favor. With the water so low, there was no way the salmon was going to leave the pool, which was fine with me, since I had no backing on my reel, and had already proved my inability to chase after him. Our fight consisted of short, strong runs wherein the salmon proved he could take line out anytime he wanted, and continued stubborn pressure on my part, proving I was not without power myself. With the rod being so light, the tippet so frail, the exact ratio between the salmon’s force and my force was delicately balanced, and if there was any skill involved it was the adjustment and readjustment needed to keep the equation constant.

After each surge, I managed to get the salmon closer, to the point where I could see him now, angled down in the crystal green water of the pool, the fly right in his jaw where it should be, his flanks a buttered silver color, his tail powerful and square. He was a good fish, not a huge one, but not a grilse either, and I estimated his length at over two feet. Up on shore my wife and baby were cheering me on, only they had been joined now by another forty people at least. Picnickers, bikers, fishermen, hikers—the woods had been empty when I hooked the salmon, but now people were materializing from the trees as if summoned by bush telegraph, and they alternated between calling out advice to me and discussing among themselves the chances of the fish getting away. Here I wanted to be alone with the experience—my first salmon!—and I had a cheering section, and it made it all ludicrous somehow, the mob up on shore adding a harder tug I wasn’t sure I could handle.

Between the lip of the pool and the granite shelf was a towel-sized patch of sand, and—netless—this is where I decided to try and beach the fish. Each time he came in, I brought him a bit closer, letting him get used to seeing the sand, not bothering him when he turned back toward the pool’s center. I had learned the first time I fought a fish his size (see below) that a long battle becomes psychological as much as physical—exhausted, you become indifferent to the outcome, and you’re apt to try and snap out of it by forcing the fish. I was fighting this temptation more than the fish now, and after about ten near approaches I decided enough was enough and pulled the salmon toward the sand as hard as I dared.

And, to my surprise, it worked—the salmon with hardly a protest slid himself up on the beach and lay still. There is no use trying to describe my emotions—anyone who has landed a big fish will know the mingled triumph and relief, and anyone who hasn’t will find it impossible to imagine what a bizarre sick feeling it leaves in your gut. I was happy of course—I turned toward my audience and threw my arms up like a hockey player celebrating a goal—but almost immediately I was faced with a new problem, this one the thorniest yet.

What to do with the fish. During our fight I’d acted under the assumption I was going to release him unharmed—unharmed, that is, if he survived the acid buildup that causes so many released salmon to later die. If anything, this resolution became firmer as the fight wore on, since it seemed ridiculous to think of a fish that had come so far, past gill nets and trawlers and oil spills and so many other perils, dying at the hands of a picnicking vacationer.

The crowd, though, thought otherwise; all through the fight they were operating under the assumption I was going to not only keep the fish but eat him as well. It’s hard to say how this feeling manifested itself, but it did, and though I’ve withstood my share of peer pressure in my day, this was about the most concentrated dose I was ever subjected to at once. These were local people, good Acadians, and the only logical destination for a migrating salmon was their pot. That didn’t square with my own philosophy, but I was on their home ground, a visitor, only it was my fish, to do with what I pleased—wasn’t it? Back and forth I went, and there were several times during the fight when I was tempted to deliberately snap the leader, disburden myself of this ethical dilemma.

The fish landed now, I was quickly running out of time. Keep him and maintain hero status with the crowd? Release him and keep the sense of my immaculate self? It would have taken Immanuel Kant to reason through this, but then I was saved by a man calling out from the hemlocks where the crowd was thickest.

“You have your salmon permit, don’t you, mister?”

I had no such thing. There was an audible sign of disappointment with that—obviously, the fish would have to be put back before a warden arrived. Relieved, I took the fly out of the salmon’s jaw and began working him back and forth through the water. Ten minutes later, when I released him, only my wife and daughter remained to watch.

But still, the news traveled fast. A few minutes later, when we were walking back down the path toward the campground, happy, hot, and tired, a man met us carrying an old steel fly rod with a huge automatic reel. He was small and wiry, and looked to be in his seventies; he had a pipe in his mouth and wore an old stocking cap, and there was something stooped in his posture that made you think he was portaging an invisible canoe.

“Are you the man who caught the salmon?” he asked.

I allowed as it was indeed me.

“Your first salmon?”

I nodded.

“On your first cast?”

I nodded again.

“On your first salmon river?”

“Well, yes,” I said, and there’s no describing the look of amazement and envy that came over the man’s face.

“Mister,” he said, his head sinking toward his chest as if the canoe had just gotten heavier. “I’ve been fishing this river for twenty-five years and never caught even one.”

In the late 1970s, learning to write, single, broke, I spent the year making a slow counterclockwise progression between temporary homes. Cape Cod in the summers, stretching fall there until the pipes in my unheated cabin began to freeze, then—throwing manuscripts, typewriters, and fishing tackle into my Volkswagen—the winter renting various houses in the quiet hills of northwestern Connecticut. In between were periods of rest and recuperation at my parents’ home in New York. One of these intervals was in November, and looking around for something to fill up my time, I decided upon a little trout fishing out in Suffolk County on Long Island’s eastern end.

That Long Island—the ancestral home of concrete—even has trout fishing will come as a surprise to many. Back in the nineteenth century it was an unspoiled pastoral landscape of surpassing beauty, and among its delights was trout fishing of a very high order indeed. The early American fishing writer Frank Forester, in an appendix to a revised edition of The Compleat Angler, raved on and on about the delights of Island trout fishing.

Long Island has been for many years the utopia of New York sportsmen . . . trout fishing still flourishes there and is likely to flourish as long as grass grows and water runs . . . it abounds in small rivulets, which, rising in the elevations midway along the Island’s length, make their way without receiving any tributary waters into their respective seas . . . the brook trout are found in abundance and in a degree of perfection which I have seen equaled in no other waters either American or British.

Poor Forester! He must be thrashing about in his grave to see what man has wrought there, and yet in what can only be described as a miracle, a fragment of this idyllic fishery remains: the Connetquot River on the Island’s south shore. Located within a defunct private club, managed now by the state, the beautifully clear Connetquot is a river I fished often once upon a time, and I’ve never visited a place that in its unspoiled perfection, its lost-world kind of atmosphere, gave me such a sense of time suspended, the past regained. If Proust were a flyfisher, this would be his stream—it’s the madeleine of trout rivers, and I loved it very much.

The Connetquot is run, very sensibly, on the British beat system. You call, make a reservation, then check in at the gatehouse and select your stretch of water. In November, the pressure falls off, and this particular day was so cold and ominous I was the only fisherman who showed up; there was a note tacked to the gatehouse door instructing anyone who stumbled along to leave their five dollars in the box and help themselves to the river. Swaddled in thermal underwear and sweaters, toting a thermos of tea and bourbon, I did just that.

Past the gatehouse is the clubhouse, a weathered old building that even abandoned suggests a kind of leisured elegance, so you half expect Jay Gatsby to pull up in a shiny Stutz roadster. It faces the lake where the Connetquot opens behind a small dam; the road crosses the dam, and on the abrupt downstream side is one of the best beats on the river: a broad pool flanked by a picturesque old mill. Unlike the water above the dam, the pool can be reached by sea-run browns, and I’d heard rumors about fish so big they were scarcely credible. Rumors—only back in the spring, crossing above the pool on my way upriver, a fisherman fighting a small trout asked me to hold the net for him, and as I dipped it in, a monstrous shape appeared from the pool’s depths, took a swipe at the hooked trout, missed, and vanished back whence it had come.

There was no one fishing the pool, but I decided to save it for later. I hiked around the lake through the pitch pine forest, fished the stream above, and caught several decent rainbows. The weather, bad to begin with, now turned vile, with snow mixed in with sleet, and aside from what the frigid air and water were doing to my torso, there was the added inconvenience of having the guides of my rod freeze up, so that casting was like whipping slush.

I was a tougher fisherman in those days, but even so there were limits. Toward noon, I’d had enough, and started back toward the gatehouse. Walking helped warm me up—between this and the “one last cast” theory, I decided to fish the pool below the dam.

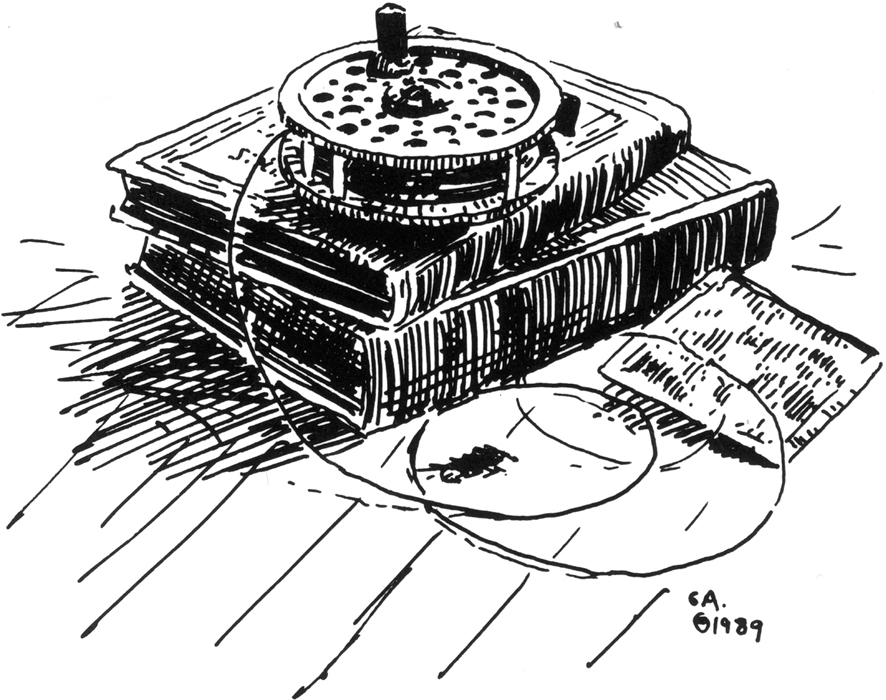

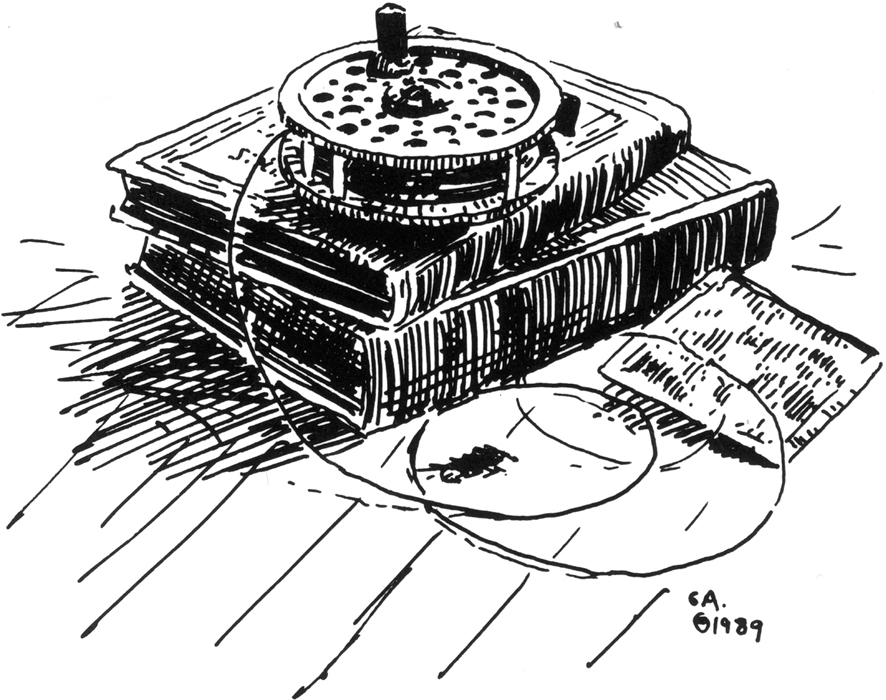

I went in on the left bank. It’s an abrupt drop-off there, but being right-handed, fishing downstream, it would allow me to get the longest drift. The water comes into the pool in a heavy gray surge from the spillway, churns through the middle, then widens into the broad, placid tail. I tied on a brown Matuka, the New Zealand pattern that was all the rage, then, with the steep bank rising behind me, I roll cast out into the current and let the streamer swing down.

I hadn’t been casting long when a brown caught hold of the Matuka and skittered across the pool toward me. He was small, and I was hardly paying any attention to bringing him in, when between one moment and the next the middle of the pool fell away, as if a petcock had suddenly been opened in the river bottom. But no—that simile isn’t violent enough. As if a depth charge had gone off in the pool’s center, so what I was aware of was the odd, backward sensation of seeing the water implode.

If the rise of that salmon on the Cheticamp was so measured and graceful it gave me time to see it all in slow motion, this was exactly the opposite experience—it happened so fast it’s recorded in my memory as a bewildering blur. At about the same instant I realized something had slashed toward the trout I was playing—a rogue alligator? a misplaced shark?—my rod bent double and nearly snapped, and I remembered, with an emotion that nearly snapped me double, the monstrous trout that had frightened me back in the spring.

If it wasn’t he, it was surely his brother—his big brother. I’d always heard browns turned cannibal when they reached the right size, and this was evidence of the strongest, most vicious sort. Engorged with the smaller trout, the brown turned toward the middle of the pool, giving me a good view of his huge, incredibly powerful tail—in turning, he left a shadow in the water that was part silver, part cream. That it was the largest trout I’d ever seen or even thought about was obvious at once; that I was attached to it seemed a hallucination.

Fight back, I told myself. Fight back! I was charged up now, ready to follow him down through the marshes to the Atlantic, but he hardly seemed concerned with what little pressure I dared apply. He lived in the center of that pool and in the center of that pool he was going to stay, and we both knew my leader was too miserably light to do anything about it. I thought about changing my stance, applying pressure from another direction, but with the bank so steep, the drop-off so sudden, I was stuck. The best thing to do, at least for the time being, was to stay where I was, keep the line tight, and await developments.

These were not long in coming.

(Remembering my disclaimer at the beginning of this essay, I write the following two paragraphs in the full knowledge not a single one of my readers will believe them, yet every word is true. The only thing I ask you to remember is how the laws of probability necessarily imply the improbable—that a tossed penny, tossed frequently enough, will eventually land on its edge.)

The trout was toward the middle, placid part of the pool, deep, but not so deep I couldn’t see him. There was no sign of the smaller trout he had swallowed or the fly the smaller trout had swallowed to start the chain off, yet my leader ran straight down the big fish’s mouth (I remember wondering if, when it came time to brag of him, it would be more accurate to say I caught him on bait or the fly). My pressure, light as it was, irritated him enough that he swung his head around and started calmly back in my direction, thereby changing the angle enough that the hook came loose.

I stripped in line furiously, unable to come to terms with the fact the big trout was gone. Instinctively, doing it faster than I write these words, I swung line, leader, and trout-impaled fly back into the center of the pool. Again, the bottom of the water seemed to drop away, again the rod bent double, and not more than ten seconds after I lost him, the big trout—the big cannibalistic gluttonous suicidal trout—was on again.

There the two of us were, bound tight to each other in a swirl of frigid gray water, fish and man. The snow had dropped back again, stinging my eyes; my legs were numb from iciness, my arms all but palsied from the effort of holding the rod. A few yards away was the trout, bothered himself now, the hook embedded at an angle that must have plugged directly into his nervous system and hurt something essential, coming back to me with grudging reluctance, his thoughts filled with—what? Anger? Homesick memories of the ocean where he had spent his adolescence? Guilty reminiscences of all the smaller trout he must have eaten to obtain his weight? Or was his entire awareness centered in that sore, relentless ache in the jaw that meant his time was up? We swam in our misery together, danced our stubborn dance, and for upwards of an hour stayed attached in that partly sweet, oddly bitter symbiosis that is playing a fish of size.

The rest of the story doesn’t take long to tell. Gradually, over the space of that hour, we were both weakening, and it was merely a question of who would reach exhaustion first. As in any epic of endurance, there were minor battles won and lost, various swings in the pendulum of fate, but twenty years later these have all been lost in the predominant, simplified memory of my tug versus the trout’s.

Toward the end another fisherman appeared. With over forty beats on the river to choose from, he had reserved the pool by the dam, and he didn’t act pleased to find me there.

He was a cool customer altogether; looking down from the spillway, he could see the trout quite clearly, but he hardly seemed impressed. I asked to borrow his net and he scaled it over to me, then, with a sullen expression, starting casting as if neither I nor the fish were there.

The trout was coming closer now, to the point I could start worrying about how to land him. The net was far too small to do the job, which left beaching him as the only alternative—beaching him, only there wasn’t any beach. Behind me was the steep mud of the bank; to my right, the deep water near the dam; to my left, bushes and saplings that overhung the bank far enough to push me out over my head.

It was the bank then—that or my arms. I had the fish close to me now—he was so large I was shy of looking at him directly—and by increasing the pressure just a little I was able to swim him around so he rested between my waist and the bank. Coaxing my legs into motion, I waded in toward him, gradually narrowing the space he had left to swim, until there was less than a yard between him and shore. Again, there was no shelf here—it was like backing him against a wall. Finally, with a dipping, scooping motion, I got my arms under his belly, lifted him clear of the water . . . held him for a moment . . . then, just as I tensed my muscles prior to hurling him up the bank, watched helplessly as he gave that last proverbial flopping motion, broke the leader, and rolled back free into the pool from whence he came.

How did I feel? How would you feel?—that multiplied by ten. While obviously I never had the chance to put the fish on the scales, I’d had him in my arms for a few seconds, and kept a clear view of him for over an hour before that. I put his weight at eight pounds (no, I put it at twelve pounds, but I’m going to reduce it to cling to what credibility I have left, though reducing it is the only lie in this essay). An eight-pound brown trout—a fish that would be large for Argentina, let alone Long Island. I knew, with a feeling beyond words, that it was the biggest trout I would ever have a chance for, and that the rest of my angling career would be nothing but a futile search among lesser fish for his peer.

Melodramatic, perhaps, but I was slow to snap out of the bitter aftertaste losing him had left. In one sense I had landed the trout, if landing meant getting him out of the water into my arms, and in any case I’d decided during the midst of our fight to release him. There was some comfort in this, but when I shuffled my way out from the pool onto dry land, I was shaking with cold and stiffness and disappointment, and something even more intense I didn’t believe existed until then: buck fever.

To be that close to something immense, to fight it for what from the trout’s point of view was life or death, to have it and lose it in the very same instant—these were the ingredients tangled together at the emotion’s core. But there was more that’s harder to explain. It was as if during those minutes I was attached to him, all the civilized, dulling layers that separate me from my ancestral, elemental self—the hunter and gatherer that, reach back far enough, dwells in us all—had been tugged away, giving instinct its chance to romp through my nervous system in the old half-remembered patterns, so what I felt was the sick nauseous human emotion of a hunter at the end of the chase.

It didn’t last very long, at least in one respect. In five minutes I was back at my car, dumping ice out of my waders, pouring the warm tea and bourbon directly over my toes. And yet a trace of that emotion lingers on to this day, as if the trout had been attached so long and fought so determinedly he welded a circuit between myself and that ancient, vaguely suspected self—the self that once fought giants and defeated a few and knew what disappointment was right down to the thrilling marrow of the bones.