3 Industrial Farming and the Illusion of Food Security

Nature created coal and oil by fossilising the living carbon of plants and other organisms over six hundred million years. In a short two hundred years, we learned to mine and burn the biological matter that the earth had fossilised. She left it underground so that we could leave it underground. Instead, we mined and mined to extract coal and oil, destroy the earth, her forests and farms, her soil and water, her climate systems and biodiversity, chasing the illusion that creating the heavy polluting infrastructure of oil was an indicator of progress.

The fossilised paradigm has created four illusions. The first is the illusion of separation and mastery—that we are separate from the earth, are her owners, masters and manipulators. I refer to this illusion as ecological apartheid. The German scientist Justus von Liebig referred to it as the metabolic rift. The second illusion is that the earth represents raw material, which derives value only through extraction and exploitation. The extraction of fossil fuel created the entire edifice of extractive technologies and extractive economies. The third illusion is anthropocentric: that the earth’s resources are intended only for humans and that humans are superior to other species which are to be owned, manipulated, exploited, engineered and made expendable. The fourth illusion is that indigenous ecological cultures and civilisations, which are non-industrial and fossil fuel-free, are backward and primitive because they create and sustain the infrastructure of life based on co-creation and co-production. Indigenous cultures are sophisticated in terms of their ability to live in harmony with biodiversity—80 percent biodiversity is on the 20 percent land where Indigenous peoples live.1

Development was defined in the Age of Oil as the use of fossil fuels and petrochemicals, of plastic and pesticides derived from oil. The pollution from the Age of Oil is everywhere for us to see. The disruption of the climate system is not as visible a form of pollution as plastic waste, nor is the pollution of our food with pesticides and toxic agrichemicals.

Non-violent, biodiverse, living carbon economies and the technologies of biodiversity in indigenous cultures have been violently displaced by dead carbon economies and technologies of fossil fuels and their toxic derivatives. Indigenous peoples knew of fossil deposits before the Age of Oil and used them in tiny quantities. Across the world, local communities are now pitted against the destructive impact of the extractive industry of coal and oil, as well as the toxics and poisons that are derived from petrochemicals. The practices and actions that drive climate change have led to biodiversity loss and species extinction; they have also created the hunger, malnutrition and health emergencies.

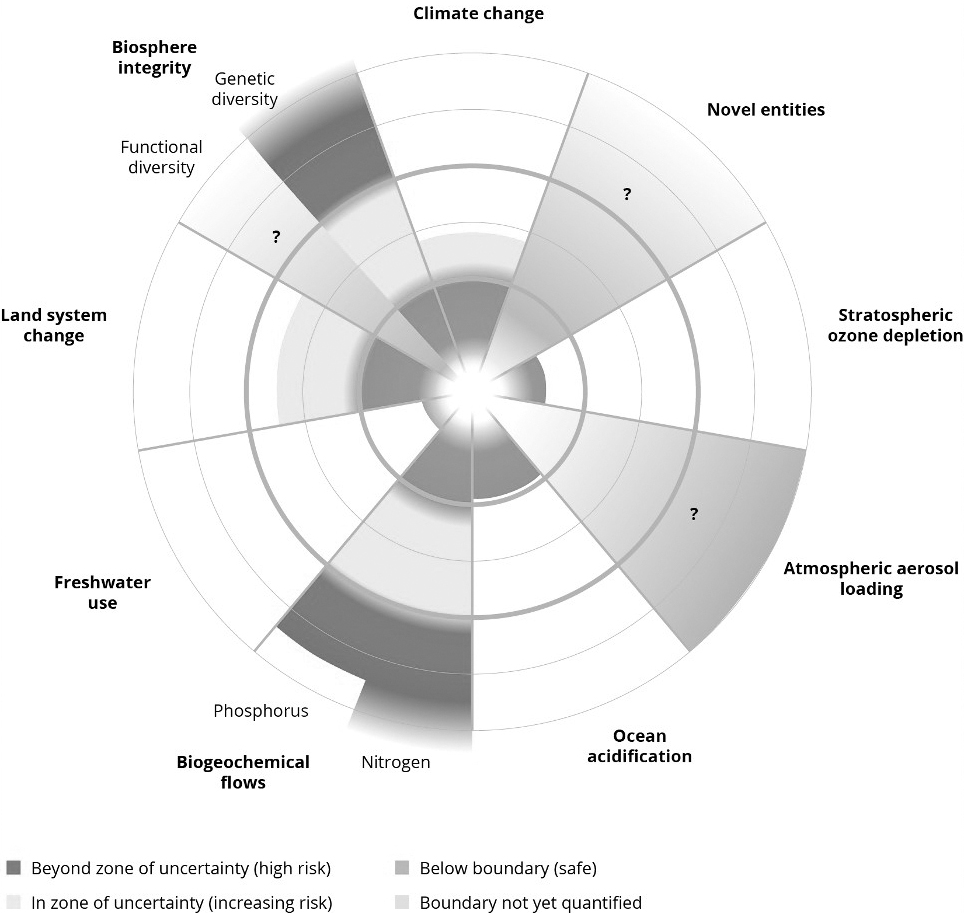

Estimates of how the different control variables for planetary boundaries have changed from 1950 to the present.

(Source: W. Steffen et al., ‘Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet’, Science 347, no. 6223 (January 2015), cited in Shiva, et al., Seeds of Hope, Seeds of Resilience [New Delhi: Navdanya/RFSTE, 2017], 5, https://

Industrial agriculture and globalised food systems

The earth has planetary boundaries; its most seriously ruptured boundaries are those of biodiversity/genetic diversity and nitrogen. The erosion of genetic diversity and the transgression of the nitrogen boundary have already crossed catastrophic levels. Industrial chemical agriculture is based on external inputs of nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium, and on industrial monocultures of globally traded commodities. Industrial monocultures are an important driver of destruction and erosion of biodiversity, both in forests and on farms. The Amazon and Indonesian rainforests are being destroyed due to the monocultures of Roundup Ready soyabean and palm oil.

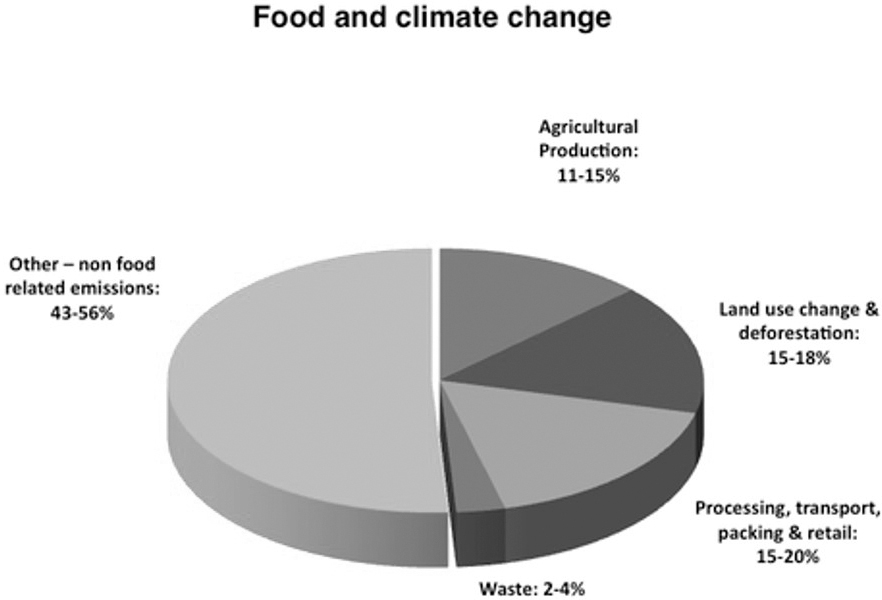

- Deforestation by agribusiness contributes to 20 percent of GHGs.

- Land use change and deforestation, including GMO soya, are reducing the Amazon rainforest by 15–20 percent.

- Processing, transport, packaging and retail of industrial food is responsible for 15–20 percent of GHGs.

- Waste emits 2–4 percent of GHGs.

From the way food is grown today to the way it is processed and then distributed, every step has a bearing on climate change. The pie chart below shows the extent of the impact made by each stage of industrial food production.

(Source: GRAIN)

Chemical intensive agriculture contributes between 11 to 15 percent of GHG emissions, of which nitrous oxide, released by synthetic fertilisers, is the main culprit. Artificial fertilisers are made by burning fossil fuels at high temperatures to fix atmospheric nitrogen through what is called the Haber–Bosch process.

As the second segment of the pie chart shows, land use change, especially deforestation, is another factor that greatly impacts climate change, contributing between 15 to 18 percent of GHG emissions. Biodiverse and sustainable farms have switched to chemical monoculture cultivation, and forests are being cut down to cultivate palm and soyabean or to become grazing grounds for cattle to provide meat for the fast-food industry.

The industrial processing and ultra-processing of food not only robs it of vital nutrients and its subtle thermal qualities but also majorly aggravates the climate situation as it spews carbon dioxide into the atmosphere through the use of fossil fuel as a source of energy. Further, when food has travelled thousands of miles, by road, air or rail, it contributes neither to your health nor to the planet’s. Since supermarkets and mega retail outlets require long shelving time, all products are heavily packaged, which again aggravates the situation.

Food waste, caused by long-distance transportation and globalised food chain production, privilege uniformity; 50 percent of the food in North America is wasted in its journey from the farm to the table. America throws away nearly half its food.2

Fossil food systems are toxic systems, based on technologies of extermination and death. Synthetic fertilisers kill soil organisms, pesticides and insecticides kill insects, herbicides kill plants. One million species are threatened with extinction; 200 disappear every day.3

Rachel Carson, author of the prophetic Silent Spring, claimed that at the heart of our motivation to introduce poisons into the environment lies a deeply-held and outdated philosophy: ‘The “control of nature” is a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man.’4

According to the Inter-Governmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES),

Rapid expansion and unsustainable management of croplands and grazing lands is the most extensive global direct driver of land degradation, causing significant loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services—food security, water purification, the provision of energy and other contributions of nature essential to people. This has reached ‘critical’ levels in many parts of the world.

Professor Robert Scholes from South Africa, co-chair of this assessment, with Dr Luca Montanarella of Italy, warned, ‘With negative impacts on the well-being of at least 3.2 billion people, the degradation of the Earth’s land surface through human activities is pushing the planet towards a sixth mass species extinction…’5

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), over-exploitation and agriculture are the ‘big killers’ with the greatest current impact on biodiversity.6 A 2017 German study has shown that 75 percent of its insects have disappeared.7 Another study in 2018 from France has called the disappearance of birds in France a ‘biodiversity oblivion’.8 Yet another study on the effects of pesticides, published in 2023, found there are around 800 million fewer birds in Europe now than there were 40 years ago, a drop of 25 percent. In wild farmland birds, which rely on insects for food, the decline is 60 percent.9

BirdLife International’s authoritative report State of the World’s Birds 2022 estimates that there are now nearly three billion fewer wild birds in Canada and the US than a few decades ago.10 Farmland practices are also driving a bird population decline across Europe.11 Researchers have found that increased farm sizes resulted in a 15 percent decline in bird diversity in the region.12

The interrelated aspects of the ecological crisis are creating new vulnerabilities for food and farming. According to WWF’s 2018 Living Planet Report, since 1970, when industrial agriculture and chemicals began spreading, we have wiped out 60 percent of the animals on the planet, and freshwater species declined by 83 percent over the same period. Since 1960, the global ecological footprint has increased by more than 190 percent! Globally, the extent of wetlands was estimated to have declined by 87 percent since 1970.13 ‘We are sleepwalking towards the edge of a cliff,’ warns WWF’s Mike Barrett.14

The above evidence indicates how, in spite of its vital importance for human survival, biodiversity is being lost at an alarming rate, as hundreds of species disappear daily with the spread of chemical intensive, capital intensive agriculture. This poison-based, monoculture-based agriculture is wiping out the huge diversity of crops we once grew and ate; humans consumed more than 10,000 species of plants before globalised industrial agriculture became widespread.

The commodification of food has reduced the crops cultivated to a dozen globally traded commodities.15 In India, we evolved 200,000 rice varieties, 1,500 mango and banana varieties and 4,500 varieties of brinjal. We bred our crops for diversity and nutrition, taste, quality and climate resilience. Today, we are growing a handful of chemically grown commodities which are nutritionally empty and laden with toxics; 93 percent of our crop diversity has been pushed to extinction through industrial agriculture. We are facing a severe crisis of malnutrition—India is 99th on the hunger index.

As the Leipzig Conference on Plant Genetic Resources acknowledged in 1996, 75 percent of the disappearance of agricultural biodiversity was due to the introduction of ‘modern varieties’. It was also recognised that ‘the imposition of WTO and the globalisation of industrial agriculture has led to further acceleration of the disappearance of diversity’.16

It was in Leipzig that the feminist scholar Maria Mies and I issued the Leipzig Appeal to say ‘No to GMOs and No to Patents on Seed’.

The Leipzig Appeal, written almost three decades ago, is as relevant today as it was then. Though many initiatives have been taken, the world over, to reclaim Food Security, Food Safety and Food Sovereignty at individual and community levels, the industrial food system continues unabated to impose its dystopia.

Climate change, desertification and the water crisis

Synthetic nitrogen fertiliser is the basis of fossil fuel-based industrial agriculture. The Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) has linked it to ‘laundering fossil fuels in agrichemicals’. Ecological agriculture regenerates the living soil through the circular economy of what Sir Albert Howard referred to as the ‘law of return’, of giving back to the earth part of what the earth gives us. Liebig, the founder of modern organic chemistry, called it the ‘law of recycling’.

Commercial interests transformed soil fertility into external inputs. Initially, trade in Guano18 from Chile was promoted for inputs in nitrogen fertiliser; eleven million tonnes of Guano were used up in less than 20 years. That is when two scientists from IG Farben (the cartel that worked for Hitler), Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch, developed the Haber–Bosch process of heating fossil fuels at high temperatures of 400–500°C under 200–400 atmospheres of pressure. This allows the double bond of nitrogen in the air to split and join the hydrogen from the gas, creating ammonia, which becomes liquid when cooled. From liquid ammonia, ammonium nitrate is produced which is then used in bombs and explosives. The same process also produces nitrogen fertiliser.

Giant factories producing fertiliser based on the Haber–Bosch process ‘drink rivers of water, inhale oceans of air’ and burn 1 percent of the earth’s energy. The manufacture of synthetic fertilisers was likened to ‘pulling bread from air’.19 The reality that was hidden by this description was the fact that synthetic fertilisers are fossil fuel and energy intensive. One kilogram of nitrogen fertiliser requires the energy equivalent of two litres of diesel. In 2000, energy used during fertiliser manufacture was equivalent to 191 billion litres of diesel, and is projected to rise to 277 billion litres in 2030. This is a major contributor to climate change, yet it is largely ignored. One kilogram of phosphate fertiliser requires half a litre of diesel.20

Nitrogen fertilisers also emit a greenhouse gas, nitrous oxide (N2O), which is 300 times more destabilising for the climate system than CO2.21 According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), N2O emissions have increased 45 percent due to an increased use of nitrogen fertilisers since the 1980s. Emissions over the life cycle of synthetic fertiliser manufacture and use are extremely significant. As per CIEL reports, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), petroleum feedstock use for the fertiliser industry is projected to be 100 billion cubic meters in 2025. Since the 1950s, when fertilisers were pushed into the countries of the South through the Green Revolution, fertiliser use has increased ninefold, reaching a staggering 123 million tonnes in 2020.22

Synthetic nitrogen fertiliser is responsible for about 2 percent of global GHG emissions, which is more than the commercial aviation sector, with 38 percent being a result of its production. The global life-cycle of CHG emissions from nitrogen fertiliser, as assessed by CIEL in their 2022 report, Fossils, Fertilizers, and False Solutions, is as follows:

- Transport: 29.8 million tonnes of CO2

- Manufacturing: 438.5 million tonnes of CO2

- CO2 emissions from decomposition: 86.0 million tonnes

- N2O from fertiliser applications: 379.9 million tonnes of CO2e [carbon dioxide equivalent]

- Indirect N2O emissions from nitrogen lost to waterways: 130.1 million tonnes of CO2e

- Total emissions: 1,129.1 million tonnes of CO2e

Since synthetic fertilisers are fossil fuel-based, they not only contribute to the disruption of the carbon cycle, but also disrupt the nitrogen cycle and the hydrologic cycle—both because chemical agriculture needs ten times more water to produce the same amount of food than organic farming and because it pollutes the water in rivers and oceans. Fertilisers rob the soil of nutrients and leave it desertified.

When the full costs of production, use and pollution from synthetic fertilisers are added, ecological, regenerative agriculture becomes an imperative. The alternatives to fertilisers that regenerate the soil are diverse. Pulses fix nitrogen non-violently in the soil, instead of increasing dependence on synthetic fertilisers produced violently by heating fossil fuels to 500°C. Chickpea can fix up to 140 kilos of nitrogen per hectare, and pigeon-pea can fix up to 200 kilos of nitrogen per hectare, non-violently. We don’t need lab-made foods for proteins. Our dals provide protein to us while also fixing nitrogen for the soil.

Returning organic matter to the soil builds up soil nitrogen. Studies carried out by Navdanya over a period of twenty years comparing the soils of chemical and organic farms in the Doon Valley, Uttarakhand, revealed that organic farming increases the nitrogen content of soil between 44–144 percent, depending on the crops grown. The comparison was drawn between farms that were practicing chemical and organic farming on a continuous basis for a period of five years.23

Since war expertise does not provide us with expertise about how plants work, how the soil works, how ecological processes work, the potential of biodiversity and organic farming was totally ignored by the militarised model of industrial agriculture.

Integrating pulses in organic agriculture is the only sustainable path to food and nutritional security. This is the integration of life and the intensification of ecological processes, not the integration of power and intensification of chemicals, capital and control. Pulses are truly the pulse of life for the soil, for people and for the planet. They give life to the soil by providing nitrogen, and this is how ancient cultures enriched their soils. Farming did not begin with the Green Revolution and synthetic nitrogen fertilisers. Whether it is the diversity-based systems of India—Navdanya and Baranaja—or the Three Sisters, planted by the First Nations in North America,24 or the ancient milpa system of Mexico, beans and pulses were vital to indigenous agroecological systems.

Sir Albert Howard writes,

Mixed crops are the rule. In this respect the cultivators of the Orient have followed Nature’s method as seen in the primeval forest. Mixed cropping is perhaps most universal when the cereal crop is the main constituent. Crops like millets, wheat, barley, and maize are mixed with an appropriate subsidiary pulse, sometimes a species that ripens much later than the cereal. The pigeon-pea (Cajanus indicus Spreng.), perhaps the most important leguminous crop of the Gangetic alluvium, is grown either with millets or with maize…

Leguminous plants are common. Although it was not till 1888, after a protracted controversy lasting thirty years, that Western science finally accepted as proved the important part played by pulse crops in enriching the soil, centuries of experience had taught the peasants of the East the same lesson.25

Vegetable protein from pulses is also at the heart of a balanced, nutritious diet for humans. The benevolent bean is central to the Mediterranean diet. India’s food culture is based on ‘dal roti’ and ‘dal chawal’. Urad, moong, masoor, chana, rajma, tur, lobia and gahat have been our staples. India was the largest producer of pulses in the world. Pulses have been displaced by the Green Revolution monoculture, and now by the spread of monocultures of Bt Cotton and soyabean.

Biodiversity is a complex food web, teaming with earthworms, bacteria and fungi. Microfungi can fill between one-tenth and three-tenths of the area around plant roots, especially in undisturbed soils. Around 100 to 500 earthworms can live beneath 0.8 square meter (one square yard) of grassland or forest. Nearly 10 million nematodes, or unsegmented worms, can live beneath almost 0.8 square meter of soil. A 0.8 square meter patch of soil can contain 500 to 200,000 arthropods (insects such as beetles, ants and wood lice), spiders and mites. A teaspoon of healthy soil can contain between 100 million and 1 billion bacteria.26

It is this amazing biodiversity that maintains and rejuvenates soil fertility and supports agriculture. Living soil was forgotten for an entire century with very high costs to nature and society. An exaggerated claim was made that artificial fertilisers would increase food production and overcome all the ecological limits that land places on agriculture. Today, evidence is growing that artificial fertilisers have reduced soil fertility and food production and contributed to desertification, water scarcity and climate change. They have created dead zones in oceans.

Synthetic fertlisers destroy the soil-food web, thus undermining soil fertility and productivity. Moreover, their runoffs (90 percent) create dead zones and they emit N2O, which is three times more damaging than CO2. Fertiliser response, too, has reduced dramatically: over a period of thirty years, it went down from 13.4 kg grain/kg nutrient in 1970 to 3.7 kg grain/kg nutrient in 2005 in irrigated areas,27 while in 1970, only 54 kg NPK/ha was required to produce around 2 t/ha, and some 218 kg NPK/ha was used in 2005 to sustain the same yield.28

Liebig was the first scientist to explain the role of nitrogen in plants, which was quickly appropriated by greed for commerce. A new industry was created for external inputs of nitrogen, dubbed ‘growth stimulants’. Outraged at the distortion of his scientific findings, he wrote The Search for Agricultural Recycling in 1861. Liebig’s book was the voice of a true scientist, protecting his truth from distortions of a pseudo-science being created by commercial interests. He writes,

I thought it would be enough to just announce and spread the truth, as is customary in science. I finally came to understand that this wasn’t right, and the altars of lies must be destroyed if we wish to give truth a fair chance.

The truth that Liebig was defending is that soil is alive, and its life depends on recycling. The lie he wanted to destroy is what he called the ‘chemical hocus-pocus’, that you can keep extracting nutrients from the soil, giving nothing back, and still obtain high yields. He questioned the false metric of ‘yield’, which merely measures the weight of the nutritionally empty commodity that leaves the farm. It is a measure of farming as an extractive industry, not of real farming. It is an illusionary measure that does not count the total biodiverse output, the total cost of inputs or the state of the soil and the farm. ‘Yield’ as a construct to promote fake farming based on chemical fertilisers artificially projects the reduction of nutrition per acre as an increase in food production. Liebig emphasises that what matters is care of the land, not ‘yield of harvest’, as well as the condition in which the field is left.

In total denial of climate science and soil ecology, Bill Gates is continuing the ‘chemical hocus-pocus’ when he says that we need to use more fertiliser. ‘To grow crops, you want tons of nitrogen—way more than you would ever find in a natural setting. Adding nitrogen is how you get corn to grow 19 ft. tall and produce enormous quantities of seed.’29 Selling more fertiliser is good for the profits of the chemical industry, but it is not good either for the soil or for the climate, or for our nutrition and health.

1 Anna Fleck, ‘Indigenous Communities Protect 80% of All Biodiversity’, Statista, July 19, 2022, https://

www .statista .com /chart /27805 /indigenous -communities -protect -biodiversity /; see also Convention on Biological Diversity, ‘Indigenous Communities Protect 80% of All Biodiversity’, July 20, 2022, https:// www .cbd .int /kb /record /newsHeadlines /135368. 2 Jonathan Bloom, American Wasteland: How America Throws Away Nearly Half of Its Food (and What We Can Do About It) (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2010).

3 Katy Daigle and Julia Janicki, ‘Extinction Crisis Puts 1 Million Species on the Brink’, Reuters, December 23, 2022, https://

www .reuters .com /lifestyle /science /extinction -crisis -puts -1 -million -species -brink -2022 -12 -23. 4 Brian Payton, ‘Rachel Carson (1907–1964)’, Nasa Earth Observatory, November 13, 2002, https://

earthobservatory .nasa .gov /features /Carson /Carson2 .php. 5 ‘Worsening Worldwide Land Degradation Now “Critical”, Undermining Well-Being of 3.2 Billion People’, IPBES, March 26, 2018, https://

www .ipbes .net /news /media -release -worsening -worldwide -land -degradation -now -‘critical’ -undermining - well-being-32. 6 Monique Grooten and Rosamunde Almond, eds., Living Planet Report—2018: Aiming Higher (Switzerland: WWF, 2018), 28, https://

www .worldwildlife .org /pages /living -planet -report -2018. 7 ‘Insects Decline Dramatically in German Nature Reserves: Study’, Phys.org, October 18, 2017, https://

phys .org /news /2017 -10 -three -quarters -total -insect -population -lost .html. 8 ‘France’s Bird Population Collapses Due to Pesticides’, Return to Now, March 25, 2018, https://

returntonow .net /2018 /03 /25 /frances -bird -population -collapses -due -to -pesticides. 9 Polly Dennison, ‘Farming Linked to Decline in Birds’, LinkedIn News, May 17, 2023, https://

www .linkedin .com /news /story /farming -linked -to -decline -in -birds -5648012; see also Perrine Mouterde and Stéphane Foucart, ‘Pesticides and Fertilizers Are Driving the Decline of European Bird Populations’, Le Monde, May 16, 2023, https:// www .lemonde .fr /en /environment /article /2023 /05 /16 /pesticides -and -fertilizers -are -driving -the -decline -of -european -bird -populations _6026804 _114 .html. 10 State of the World’s Birds 2022, BirdLife International, https://

www .birdlife .org /papers -reports /state -of -the -worlds -birds -2022; see also Ian Angus, ‘Industrial Farming Has Killed Billions of Birds’, Climate & Capitalism, June 6, 2023, https:// climateandcapitalism .com /2023 /06 /06 /industrial -farming -kills -billions -of -birds. 11 Stanislas Rigal et al.,‘Farmland Practices Are Driving Bird Population Decline Across Europe’, PNAS 120, no. 21 (May 2023), https://

www .pnas .org /doi /10 .1073 /pnas .2216573120. 12 ‘New Study Shows the Toll Industrial Farming Takes on Bird Diversity’, ScienceDaily, January 12, 2022, https://

www .sciencedaily .com /releases /2022 /01 /220112154933 .htm. 13 Monique Grooten and Rosamunde Almond, eds., Living Planet Report—2018: Aiming Higher (Switzerland: WWF, 2018), 7, https://

www .wwf .org .uk /updates /living -planet -report -2018. 14 Julia Conley, ‘Humanity “Sleepwalking Towards the Edge of a Cliff”: 60% of Earth’s Wildlife Wiped Out Since 1970’, Common Dreams, October 30, 2018, https://

www .commondreams .org /news /2018 /10 /30 /humanity -sleepwalking -towards -edge -cliff -60 -earths -wildlife -wiped -out -1970. 15 The Law of the Seed, Navdanya International, May 20, 2013, https://

navdanyainternational .org /publications /the -law -of -the -seed. 16 Food and Agriculture Organization, ‘International Conference on Plant Genetic Resources to Meet at Leipzig from 17 to 23 June’, United Nations, June 13, 1996, https://

press .un .org /en /1996 /19960613 .fao3635 .html. 17 Maria Mies and Vandana Shiva, ‘Leipzig Appeal for Women’s Food Security’, June 20, 1996, https://

www .iatp .org /sites /default /files /Leipzig _Appeal _for _Womens _Food _Security .htm. 18 Guano is the accumulated excrement of seabirds or bats. It is a highly effective fertiliser due to its high amounts of nitrogen, phosphate and potassium, all key nutrients essential for plant growth. Guano was also sought for the production of gunpowder and other explosive materials.

19 Jake Marquez and Maren Morgan, ‘The Legacy of the Men Who “Pulled Bread from Air”—A Reading by Maren’, Death in the Garden, November 3, 2022, https://

deathinthegarden .substack .com /p /45 -the -legacy -of -the -men -who -pulled -beb. 20 Vandana Shiva, Soil Not Oil (New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2009).

21 P.R. Shukla et al., eds., Climate Change and Land, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2019, https://

www .ipcc .ch /srccl. 22 Dana Drugmand et al., Fossils, Fertilizers, and False Solutions: How Laundering Fossil Fuels in Agrochemicals Puts the Climate and the Planet at Risk, Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), 2022, https://

www .ciel .org /wp -content /uploads /2022 /10 /Fossils -Fertilizers -and -False -Solutions .pdf . 23 Indira Rathore et al., ‘A Comparison on Soil Biological Health on Continuous Organic and Inorganic Farming’, Horticulture International Journal 2, no. 5 (October 2018), https://

medcraveonline .com /HIJ /a -comparison -on -soil -biological -health -on -continuous -organic -and -inorganic -farming .html. 24 ‘Three Sisters’ refers to the polyculture system practiced by Native Americans in North America in which they grow a combination of corn, beans and squash.

25 Sir Albert Howard, An Agricultural Testament (London: Oxford University Press, 1921), 13, 14–15.

26 Catherine Arnold, ‘Soil (and Its Inhabitants) by the Numbers’, Science News Explores, February 25, 2021, https://

www .snexplores .org /article /soil -and -its -inhabitants -by -the -numbers. 27 For more information, refer to Low and Declining Crop Response to Fertilizers, Policy Paper no. 35, National Academy of Agricultural Sciences (New Delhi: NAAS, 2006), 8.

28 P.P. Biswas and P.D. Sharma, ‘A New Approach for Estimating Fertilizer Response Ratio: The Indian Scenario’, Indian J. Fert. 4, no. 7 (2008): 59–62.

29 Bill Gates, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster: The Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2021), 123.