2

“Oh My God—What Is That Sound?!”

Sabbath’s Early Influences

Many music fans do indeed believe Black Sabbath invented heavy metal, and, arguably more so than with any other band, this sense of invention, of coming up with something completely new…Sabbath is certainly one of the better examples of this in the story of rock, Jimi Hendrix being another crazy example that instantly comes to mind and to some extent Eddie Van Halen. And when something like this happens, the burning question of influence becomes a conflagration. Certainly burns me up, ’cos I’ve tried to get the answer to this one out of the guys on many occasions over the decades, never quite feeling like I’d gotten the whole picture or even enough satisfying pieces to the puzzle.

With Ozzy, you wind up hearing a lot about the Beatles; with Geezer, it’s Jack Bruce for bass, Robert Johnson for devil lyrics, and, on a wider plane, John Mayall, Jack’s band Cream, like Ozzy, the Beatles, and fair enough, those make sense. But talk to Tony and Bill, and you wind up hearing a bunch of jazz thrown into the mix. This doesn’t make sense but then maybe it does, given the boys’ hometown of Birmingham and its rich jazz and blues heritage going back decades.

Big Bear Music’s Jim Simpson has been in the Midlands jazz and blues business since the late ’60s, managing, running an agency, putting together festivals, releasing music on his highly respected label. What’s more, Simpson was Black Sabbath’s first manager, becoming so after having the boys back up the touring acts he would bring into Henry’s Blues House and noticing the wild response they had been getting.

“Black Sabbath were heavily influenced by jazz things in the very early days,” notes Jim, a horn player himself and owner of a bulging record collection that helped form the listening patterns of the long-haired noisemakers in Sabbath. “They were young, and, especially early in their career, they were interested in anything, really. Ozzy and Tony, particularly, seemed to lean toward it. You can’t tell with drummers and bass players, who express themselves fairly individually, but certainly if you look at the early Bill Ward stuff, you can hear some Kansas City Jo Jones high-hat rides. And certainly Black Sabbath was the great riff band, and the great riff band in jazz was Basie, and that’s where Jo Jones played. As well, Ozzy recorded a couple songs associated with the Basie band, Jimmy Rushing’s ‘Evenin’,’ for one. And, going slightly sideways, Tony recorded an instrumental called ‘Song for Jim,’ funnily enough, which was an absolute Charlie Christian takeoff.

“You won’t have heard that, because it’s never been released,” says Simpson of this legendary, largely unheard Sabbath original from 1969, as Jim indicates, very much outside of the Black Sabbath style we know.

“They never thought of themselves as being a scary band,” continues Jim, asked how we get from jazz to “Hand Of Doom.” “It was always thought of as being a heavy band, a power band. The need to frighten people actually never actually came into the conversation. And although the name is taken from a horror movie, it’s…I don’t know, it was doom and gloom, sure, but that’s not quite like horror, is it? To talk about ‘Paranoid,’ and Ozzy’s vocal on the ‘Black Sabbath’ track, those aren’t scary so much as doom-laden. It’s a different thing. I always think of scary as being sudden shocks, and I don’t think Sabbath were a sudden shock band. They were a batter-you-into-submission heavy band, weren’t they?

“We were more obsessed with being heavier and tougher than bands like Led Zeppelin,” explains Simpson. “That was the target. We carried a strapline saying, ‘Black Sabbath makes Led Zeppelin sound like a kindergarten house band.’ That was the prime objective. And neither them nor I were political as such. We all felt badly served by society; we all came from the wrong side of the tracks. But there was no conscription. Had we had conscription at the time, ongoing wars and things would have had more places in our consciousness. And in America, the Vietnam War, there was conscription, wasn’t there? So any young man growing up, thirteen, fourteen, would start sort of counting down the years until he was going to be called upon. But that wasn’t the case over here. The IRA thing always happened to someone else. All these tragedies, they’re never your tragedies; they’re somebody else’s.”

Geezer is upfront about the mighty Led Zeppelin making an impression. “One of the biggest influences was Zeppelin because two of them were from the same part of England that we were from, from Birmingham, and we used to see them in clubs and stuff around town. So we sort of associated more with Robert Plant and John Bonham than anybody else, I suppose, ’cos we were doing the same kind of circuit before we made it. There wasn’t competition, just friends. We’d see each other out and have a beer or whatever, and just socially, really. Everybody seemed to be doing their own kind of thing. There was like lots of new kinds of music coming out around, and everybody sort of had their own originality.

“Bands lasted like two or three years and then you wouldn’t hear from them again,” continues Geezer, “When we did Paranoid, the Beatles had only been together for eight years and broken up. So we thought, ‘Well, if the Beatles break up after eight years then we’ll probably last about two or three years and that’ll be it—and never to be heard of again.’ Which is a good thing, because if you could get a time machine, you probably would go back and change the music so it’s perfect and everything, and it just wouldn’t be the same. Our families had sort of thrown us out ’cos we wouldn’t get proper jobs, so they didn’t believe in it. The friends I had thought I was nuts. They just didn’t have the—I don’t know what it was; ambition’s the wrong word—I suppose the belief in the music, and we just wanted to do the music more than anything else on earth and luckily it turned out well for us. We were just doing music that we liked writing together. We never thought about it as heavy metal or anything like that. We just thought it was rock, a heavy rock kind of thing. We all loved Hendrix and Cream and John Mayall, that kind of heavy, Zeppelin. And so that was the natural sort of progression when we started writing our own stuff.”

Geezer recalls the club scene being vibrant enough in Birmingham that one could watch all this going on live. A bit hazy on the names of these places, Geezer mentions clubs like the Penthouse and the Metro as well as the usual suspects. He harbors good memories of seeing bands such as Free, Chicken Shack, Keef Hartley, the Who, and the Kinks, along with Fleetwood Mac (managed by good friend Norman Hood), Jethro Tull (which Tony would join for a couple of weeks), and Aynsley Dunbar Retaliation (Sabbath covers that band’s “Warning” on Black Sabbath).

“With Sabbath, a lot of people try and read into them more than they actually were,” warns Simpson, in tacit agreement with Butler. “They were a blues band that had come to the end of the road with the blues. I mean, British blues was getting really bad press over here, because all the bands were playing the same thing, and they didn’t really capture the feeling of…Not Zeppelin, but everybody else didn’t really capture the feeling of the blues they were trying to copy. I mean, a few bands did make it on the blues thing, but there were ten million bands all looking the same, playing the same, wearing the same denim jackets and denim trousers, smelling the same—there were a million of them. Promoters did not want to book blues bands. That’s why I opened this club in Birmingham one night called Henry’s Blues House—to give sanctuary to blues bands. There were some great blues bands being lumped in alongside the boring bands. And everyone tried to get out of it.

“The main thrust behind Sabbath was to create an identity, and not be seen as just another blues band,” continues Jim. “And that was the driving force—to be individuals. And that’s why we looked at jazz, because nobody else was looking at jazz. There were some elements. They never, ever, wanted to become a jazz act. We thought together, because of my knowledge of jazz, there might be something from jazz that we could call upon and adopt, and we used it to make our sound different to everybody else’s. In the end, when things like ‘Black Sabbath’ were written, that was the turning point, that was the direction, and the word jazz was probably never mentioned again.”

“They were originally doing sort of blues covers,” explains Norman Hood. An early friend and booker of the band, Hood eventually starting a management agency with Tony called IMA. “I suppose in a way it was their own interpretation of probably Chicago blues, but obviously with a little bit more of the old pyrotechnics. It was probably only about twelve months or so from me knowing them until they evolved into Black Sabbath. We’d booked them at my club, the Pokey Hole, which was the back room of a pub. Again, I’d have to check on the actual times of year, but probably early ’69. They went to Hamburg for a little while, came back, and it was Black Sabbath, in my pub. They announced the name change for the first time from the stage, then proceeded to take the roof off the place. Practically closed it down, in fact, because the people in the bar couldn’t keep their glasses on the table, they were that loud. So the evolution was pretty quick. They went from doing quite a lot of derivative material to writing their own very, very quickly, and the black magic thing as far as it went was sort of…just icing on the cake, really. Part of the change in name and song.”

“I was knocked out by it, totally,” continues Norman, on the band’s new heaviness. “I’d heard one or two of their own numbers, obviously. They had been playing their own numbers. But I think the mere attitude they got, more than anything else…I mean, Ozzy was always a bit of a nutter, but his attitude had totally changed when he came back. He was even more of a nutter and louder than ever. Bill was just a nice guy. He was withdrawn, slightly. Again, by comparison to Ozzy, everybody was. Bill was quiet. When I used to travel to gigs with him and so on, he was involved, but he was always slightly reserved. I know he had troubles later on, so he may have been under some pressure then, I don’t know. They used to take the mickey out of him something terrible, of course.

“I think Ozzy was born that way,” says Norman, on his impression of why Ozzy was so out of control. “He took to drink very early on. Probably other substances as well, fairly early. And it began to affect his relationship with the band. I know that they struggled to fulfill recording dates and that sort of thing. He was just a wild card. I’m a little biased because Tony was a good friend, but to me he was sort of the sensible one. He had to keep the rest in order, and I know he struggled quite badly with Ozzy.”

With respect to musical inspiration…“I don’t know if they actually had influences, as such,” reflects Norman. “I mean, everything was happening so fast in those days. Bear in mind, I’d seen Cream on their debut performance a couple years before, and that was basically still blues rock. There was no psychedelic touch or heavy tinge to them, and they were the actual cutting edge then. Then all of a sudden it was like Zeppelin and Sabbath—I suppose maybe the Who were the newest link before Sabbath. But the thing with Sabbath is they did it totally opposite to how bands had gotten noticed before. They didn’t bring a record out, they didn’t get any press other than some fairly bad press—they just worked. They played clubs, would go down really, really well, get booked back again, they were on the road all the while, and they built up a grassroots following that was just tremendous. It’s not something that could be done a few years after that. All the smaller clubs had disappeared and the college circuit was probably preeminent then.”

But the fans certainly got it, explains Norman, pretty much straightaway. “Yes. Bear in mind, my club was a very tiny place—we’d get a hundred or so people who’d come whatever we’d got on. We could put anything on and they’d be there. But the mix of people as Sabbath got better known and as they played, they built up their own following, and this is before they recorded. We began to get people from the outlying areas and from Birmingham who traveled across to us. People from out of town, which was unusual at that time. We had one or two other decent bands on, but Sabbath were the big pull, always. But Tony, he developed his sort of twenty-five-minute guitar solos, which were usually—bear in mind this was the back room of a pub—usually played with somebody hanging around his neck with a pint of beer [laughs]. And of course the volume had gone up quite considerably. But once they sort of settled into it, then it was obvious that it was something that was going to be really, really special.”

Still, back to the invention of heavy metal, these riffs seemed to come from nowhere, which, in a roundabout way, is what Norman has been trying to tell us. “Yes, well, that’s difficult. You know, Tony is heavily into blues and loves jazz. I spent quite a few nights over at his house, I mean later on—this is when they got a reasonable amount of following. He got a studio built at his house. I sat in there listening to him playing jazz guitar, fingerpicking jazz guitar, absolutely wonderfully. So, I mean, the guy is one hell of a musician. He’s far from the heavy riff-meister everybody seems to think he is. He’s a fine guitarist, and I think his influences go back through the blues and also through some of the better jazz guitarists as well. Certainly…it’s difficult speaking for someone else, you know?

“Yet I’m not sure if it was his background,” says Norman, speaking here of jazz. “It’s the music he certainly used to listen to. In fact he’s given me some blues albums that are very…I mean Sonny Boy Williamson the first, let alone the second; we’re going way back to the 1940s and so on, and I know he was a great fan of jazz guitarists like Joe Pass, people like that. I think he’s just a damn good musician. Found a formula and developed that formula.”

Bill Ward confirms Jim and Norman’s shared portrayal of a jazz root to Sabbath. “Jim is a jazz musician [laughs]; he used to play horn. Yeah, he’s a horn player and he loved jazz. That’s probably why we liked him in the first place [laughs]. For me it was big band, big band American jazz, which would be anybody from Woody Herman to Count Basie, and you know, the bands that the classic drummers played in. So that would be Louie Bellson, and for me, the king, Gene Krupa, and then obviously Buddy Rich. I listened to a lot of the ’40s drummers, and the reason why it was so influential for me was because during the Second World War, the GIs had come into Great Britain, for the second front, I guess, and they had brought with them all their records. And my mother and father were incredibly influenced by American music. So that’s how it came to be. When I was growing up as a kid, it was played in our house almost daily. So I literally was brought up with it.”

With respect to what knowledge he had been able to pick up from these records, Ward figures, “Anything and everything, but if I had to pick, I would say feel, at the top. Because there was a shine on American big bands that was completely not available with any of the other bands. I mean, I used to A/B with the British big bands at the time, and they were good, but American bands…they really knew where to put everything. And so for me I liked the swing, the sounds, I liked Glenn Miller sounds. I was like four or five years old at the time. But the Glenn Miller band, and the way that he had his particular sound put together, that was very attractive to me. ‘Moonlight Serenade’…there was a sadness and a mood that was reflected through the music, so I was already feeling all that, in my early childhood.”

As regards Tony, Bill says, “He’s got his own taste and what have you in jazz, but the biggest influence, if you like, or the biggest most-played person would have been Django Reinhardt. I know that Tony really liked Django, as I did as well. Mine was more like, as a child, until Presley, would have been Gene Krupa. But Gene Krupa all the way through my life, you know? Right up until today. And with Tony, yeah, Django was somebody that we listened to together. And I know that Tony listened to him as a kid.”

And yet again, there’s Tony inventing metal, for example, the rat-a-tat-tat machine gun–style riffing of “Paranoid,” which one supposes has its origins in “Communication Breakdown.”

“I don’t know!” exclaims Jim, asked about how we get from traditional old-timer music to tearing it up for a new generation of headbangers. “You know, someone brings something to the table, and it fits in with something that’s happening musically, and you don’t question it. You go, ‘That’s great, let’s do that.’ I mean, we were all looking around for ideas, mainly for a name for the band—that’s what we were really looking around for: musical direction. Ozzy would come around and listen to other music. I think Iommi already had some sort of…he already knew about Charlie Christian before I introduced him to him. I’m sure he had. Django—not really, because that’s a very European music. That’s the only forward jazz that’s worthwhile that did not originate in America. That’s the Reinhardt legacy. He listened to Charlie Christian, and Christian really came out of the Eddie Lang school. Joe Pass was years later. Well, Pass was okay; he was a fragile talent, made two great albums, and the rest just filled in.”

Asked what Tony might have picked up from Charlie Christian, Simpson quips, “Well, I’ve got three minutes and twenty-two seconds that says he got something from him” (and by this he confirms that he’s referring to “Song for Jim”).

In terms of then-present-day rock, figures Simpson, “Cream would have been big. Yeah, we were all aware of Clapton; I think Clapton was the benchmark to strive for. But classical, I can pretty much say, unequivocally, no.”

But it’s pretty much “Yes please, I’ll have some of that” for Bill Ward, as pertains to classical. “It’s difficult for me to talk for the others,” explains Ward, “but for me, well, I thought that the first metal was actually classical music, in the sense of, well there was some Tchaikovsky that I really liked, some Beethoven that I really liked. We didn’t hear much of Richard Wagner in my early childhood; I think I first started listening to Wagner when I was ten or eleven years old. And the darkness of Wagner was very appealing; I liked the sadness and the almost monsterlike chords that would evoke so much to the imagination. So yeah, classical music has always been there.

“But a lot of things that we were influenced by was blues and some jazz, and just some really standard-type blues things that everybody was kind of playing. So we were still very much embedded in that. We were doing versions of some John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers. Eric did…oh man, I’m trying to think of the tracks. There was one, ‘Hideaway,’ that we did. I’ve forgotten the other ones. They were both instrumentals but Clapton played lead guitar. My turn toward Eric Clapton came with the Yardbirds, but when the Yardbirds were playing at the Marquee Club—that’s when I first noticed Clapton and what he was doing. So we were still actually quite young. We were only like just coming onto eighteen years old, nineteen years old. But our first initial, really big influences were from the British blues scene, if you like, and also from what was coming from America. We had already learned all the basic rock ’n’ roll stuff from America when we were kids. I mean, when I was fourteen, I learned ‘Johnny B. Goode’—we learned all the Chuck Berry stuff. Every band back then.

“And when I first heard Elvis Presley, I was bought and sold. I was completely grounded. I was just stumped. I got it immediately. It’s like, I got it straightaway. I didn’t have to be talked to about it or convinced about it. The first song I think I ever heard was ‘Jailhouse Rock.’ And then I heard ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ and all the rest of it, and I was so gung ho on Elvis, I just thought it was brilliant.

“First of all, his singing to me was outrageous; he was singing stuff that was completely different. I had never heard such ferocity, like in ‘Jailhouse Rock,’ or the way that he would lay something down, ‘Heartbreak Hotel,’ the way he laid that down, and then the lightness of him in ‘Teddy Bear.’ I still prefer Carl Perkins, ‘Blue Suede Shoes,’ but I love Elvis’s version as well. So yeah, Elvis was just so different. There was just something about him, and I’m not talking about his gyrations or anything. It wasn’t that, for me. There was a force and a different way of playing. His drummer, I think his drummer at the time was Larrie Londin? I’m not sure about that. You might know that better than I would, but the Jordanaires and his backing band, and the guitar solos, they were all different. It was all being played differently. And the drumming didn’t seem to give a fuck about what was the normal type of drumming, how you have to play, blah blah blah, all that strict tightness or whatever. It was just loose and it just fitted and it brought freedom to me. That’s all it was—freedom.”

But like most British musicians of the era, there was also a grounding in the quieter form of original rock ’n’ roll called skiffle—footage exists of both Jimmy Page and Ritchie Blackmore partaking of this music as mere lads. I’d always associated skiffle with the UK, perhaps because of that, but not so, says Bill.…“Well, I think skiffle actually originated…for me, I mean, the first skiffle I heard was Nancy Whiskey, who is actually an American artist. And I really liked what Nancy Whiskey was doing. I bought a couple of her records when I was young. But there was a crossover in Great Britain, and it was headed by a guy called Lonnie Donegan, who had just seemed to charm…or have this complete ability to play skiffle in a very, very good way; so skillful. I think all of us were in skiffle bands when we were kids. I was only like nine or ten, where I had my washboard, and all you had to get was a washboard and somebody would get a guitar, and nobody could afford a stand-up bass, so we made those big cardboard boxes with a stick on it, pretending to it was a bass.”

I inquired of Bill whether it would be accurate to call skiffle the British response to rock ’n’ roll.

“I think in some ways. I think it might’ve been the British response to someone like Nancy Whiskey, or American folk. I think that might be more of the case, because in rock ’n’ roll, we started to have our own rock ’n’ roll heroes. It was Cliff Richard and Billy Fury, and everyone wore their collar up, and everyone wore their hair back, slicked back, and everybody looked cool—it was a great look. And of course Elvis was looking exactly like that as well.”

“I believe it came from Sabbath,” continues Jim, asked to take another crack at where the band’s particularly heavy rock roots originate from (Bill’s touch upon the Yardbirds seems to be a bit of a clue, in particular his allusions to Clapton). “I believe that somehow, the members of the band dreamt it up themselves. There’s no influence that I can see, before that, that goes in that direction. I think they made the leap. And as I saw it develop—although I was very much involved in everything they did, and had very close relationships, and we’d make use of regular meetings and thrash things out verbally all the time—but the music, as far as I was concerned, seemed to have its own life. Once we’d imported my jazz thoughts and ideas, which may have gone into their psyche at one time, once the Black Sabbath direction emerged, that was all theirs. And they weren’t listening to other people. They weren’t nicking things off of other bands. It was what they were doing. In Earth, they had songs like ‘Song for Jim,’ which was a jazz thing, which was produced under the Earth name. But I think ‘Black Sabbath,’ the song itself, that was the huge step—that song. After that, the rest sort of fell into place.”

Insistent, I wondered how Jim thought it “fell into place” as the new original compositions started to pile up, as the invention of heavy metal became to be fleshed out over the course of the first three albums.

“Well, to be honest with you, I like Black Sabbath best and I like Paranoid second best, and I like Master of Reality third best. You’ve got to remember, we…well, let’s get it right. We spent a long time on the material that went into the Black Sabbath album. There’s probably two years’ worth of work there, and then Philips wanted the second album six months later. Also, I think when you establish something new, and you create something new like that, the first step is the greatest, and it’s also the song collection of all your thoughts and ideas. Paranoid itself, the album, was slicker, and I was going to say less honest—I don’t mean less honest—but less from the heart. I think the Black Sabbath album was a real emotional creation; they did it because they’d all reached a point where they were thinking exactly along the same lines musically, and this was their first child. I think by the time it came to the second birth, they’d done it all before a little bit, nattily enough, but it didn’t have the same sort of innocence of the first. I think any musician, anyway, as he gets better, you become more guileful and find ways of doing things and it’s not quite as much from the heart—anyone.

“The kids always liked them from beginning,” muses Jim. “From the very first date they played for me, for an intermission slot, the crowd responded. Not ecstatically to start with, but there was a response, which is more than you get from most intermission bands. The press were deafening in their silence, because we didn’t fit any mold. You couldn’t say they were like so-and-so or better or like so-and-so but worse—there was no ticket to put on them. And we really battled with the media. The media was very cruel to us to start with, because they didn’t understand what was happening. And I was constantly having to make excuses for them, the media, and explain why it was good. Maybe I wasn’t aware of other bands around at the time as much as I maybe should have been. But I mean, facts will prove me right or wrong, but my feeling was that Sabbath were in front of the bands, timewise. The Purps, and who was the other one? Uriah Heep were later, weren’t they? In fact, I lost a drummer from my other band, the Bakerloo Blues Band—he went to Uriah Heep. And the Purps, they were a bit pompous, weren’t they? I mean it wasn’t real people’s music. It was stadium rock in its infancy.”

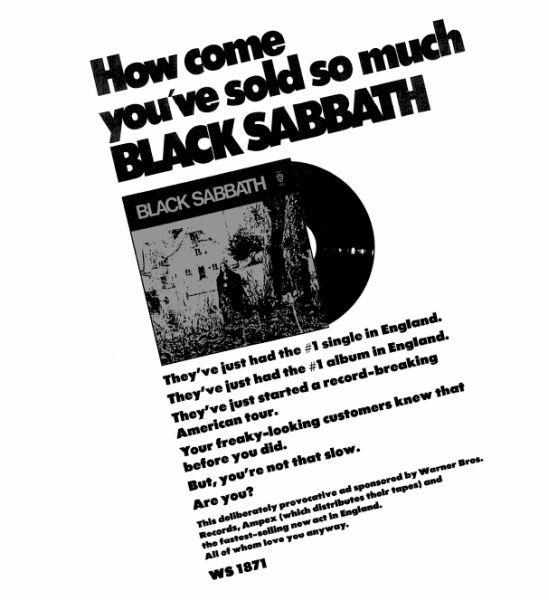

One would have to say that, in retrospect, Vertigo’s teaming with Warner Bros. rather than Mercury for North America was a good decision. The promotional copy used for the band was inventive right out of the gate, and over the years, a series of stunning print visuals would ensue.

This would lead one to believe that Sabbath seemed very much like a pronounced workingman’s band by comparison.

“Oh yeah, no sweat, absolutely,” agrees Jim. “There’s no pretension there at all. I mean, Ozzy’s honesty showed through his vocals. That’s what carried it. From the soul. Also, like some of the great jazz things like Jimmy Rushing, it comes from deep in the stomach in some way. It isn’t conjured up from the back of the mouth. It comes from deep inside. And Ozzy did holler really well. That’s a trademark of the blues.”

So in a way the blues heritage shines through, but in an abstract way.…“Oh yeah, the blues were absolutely there. They were a blues band—you must remember that. They were a blues band.”

And a Birmingham band as well, at the core, adds Jim. “Well, Birmingham…every city produces all styles of music, obviously. But the main thrust of Birmingham’s bands was always pretty tough. We’re pretty good at sort of rhythm and blues; some of the blues players out of the city were great. We’ve always had…it sounds like they were all playing the same thing, but they weren’t, but there was a predominance of really tough rhythm sections, guys who could drive; in jazz terms, guys who could swing. And that’s not a huge step to Sabbath. In fact, many of the bands were jazz-oriented, and we used to put several bands together, at a thing called Big Bear Folly, and we used to put Sabbath on the same bill, as jazz players. So they were playing along with very skilled jazz players, and that included Pete York, who was the drummer with Spencer Davis at the time, who’d been in my band for many years beforehand, although he’s more famous for his rhythm and blues playing with the Spencer Davis Group with Steve Winwood. But he was actually a jazz player at heart.”

Ward remembers Winwood as well. “Yes, well, the first success that came out of Birmingham was obviously the Moody Blues and Steve Winwood, who lived in Kingstanding, right in the heart of Birmingham. So already you could see from the Moody Blues and Steve Winwood, the kind of difference that was happening—and that was in 1965. I can remember the Moody Blues coming down our street in their blue van with ‘the Moody Blues 5’ written on it. And then there was Denny Laine and the Diplomats, before Denny joined the Moody Blues. All these bands…the place was so busy with bands. It was just an absolute pleasure of life, if you like. But the music that came out of Birmingham and around Birmingham would include Robert Plant and John Bonham, obviously, and then Judas Priest, who came a bit later.”

But being out of Birmingham always had its stigma, as evidenced by the way Simpson has come to view the band’s signing to Vertigo and his subsequent dealings with the label, from the album covers all the way down.

“We didn’t pick the album sleeves—they were given to us,” laughs Simpson. “Olav Wyper, who ran the record label, they got a designer named Keef, and he had done stuff for him, I think, in the earlier days, with CBS, and he was doing the whole Vertigo series, as I recall. And then he came up with the Black Sabbath photograph. Frankly, Philips and Olav Wyper didn’t really think much of the album at all. They didn’t really want it. They only took it because another title had fallen out, and the catalog number of VO 6 was empty, and they needed product to fill that gap. They already turned it down once. But without ever talking to Keef, the designer, I think he got it straightaway. Olav didn’t, Tony Hall didn’t, none of the people who…even Essex Music didn’t get it. But I think the designer did. I only say that because he created the perfect album sleeve, and I think the second album is certainly not so good, and neither is the third.

“What happened was, Olav worked for CBS, and maybe I’ve not got this in the right sequence, but it was something like this. EMI had their underground label, which was Harvest; I think Pye [Records] might have done Dawn, or they were in the throes of doing Dawn—I’m sure there were two out there. And then Philips decided on Vertigo as their underground label, and they headhunted Olav Wyper for that from CBS, because there was nobody at Vertigo because there wasn’t a Vertigo. So I hadn’t been to there, but I’d been to CBS, and Olav Wyper had turned me down at CBS; rejected it. He heard half of one track and a few seconds of the third track and that was it. But he remembered it. When he had the first wave of releases, VOs 1, 2, and 3, I think Manfred Mann, Rod Stewart’s ‘Old Raincoat’ and ‘Won’t Ever Let Me Down,’ and he might have Jon Hiseman’s Colosseum, and the second tranche we got another three releases, which was their policy, and VO 6 had failed to deliver a master. And Olav came to me and said, ‘Listen, that band, great band, we’ll do a deal,’ and that’s how he got involved, and that was it. So he didn’t understand it.

“And the fact that the band had a substantial fan base in the north of England and in the Midlands didn’t resonate with them at all. Because they were so London-centric. And in most instances they still are. And this fan base in the Midland and the north is of no value, because when they went to London, the band was already happening, because the record was out by then, and we got a huge audience at the Marquee, queuing around the block. So the kids were into it, but the record company was, well, clueless, like most major record companies.”

Geezer tends to corroborate Simpson’s story of struggle rather than the rosy picture of the band’s signing put forth by Wyper. Geezer talks of being turned down by seven record companies, literally having to play in their offices for them with horrified executives turning tail for the door. Come Vertigo, says Geezer, the band had to submit three demos, all covers, including “Evil Woman,” before the label would consider taking them seriously.

Back to the Sabs and satanism: Even though Simpson is adamant that the band’s dark image wasn’t a key part of Black Sabbath psyche at the beginning, that they were somewhat just learning as they went like Birmingham’s other ’60s bands, he does qualify. “I’m not saying it didn’t develop; I’m not saying they didn’t get on this particular gravy train, in years later. When I lost them, the Paranoid album was #1 on the charts, and the ‘Paranoid’ single was #2 on the charts, and Black Sabbath had come in at #16. It hadn’t been off the charts since it was released, and it had come back into the Top 20. That was looking back at pretty early days. What they got into later, I don’t know. We had a few sort of satanic run-ins. People came to us thinking the satanic thing might’ve been from the heart, but we soon disabused people of that fact.”

Not even from Geezer’s end of things? “It never came to the surface [laughs], if it was ever there. They were four kids who wanted to get themselves…they were four kids that wanted to play in a band. And to play in a band they had to come up with something different. There’s no…nothing satanic, nothing religious. The crucifix was there because they liked the shape of it [laughs]. Ozzy wore a crucifix from early on, for no reason. When you’d ask Oz, ‘Oh, I like it.’”

“It was a joke, really,” agrees Norman Hood. “It was never, ever taken seriously by the band or by us. Not at all. When it became obvious that was the way the publicity people were going to take it—Jim Simpson and the other record companies when they eventually got to record—it was just a peg to hang it on. I know Geezer was probably the one, because he wrote the lyrics; he was probably the most spaced-out of the lot. But at that stage it was just a joke. Again, you must remember my involvement was very early on. Like probably from about late ’68 through ’69 and then they started taking off then. I mean Geezer was just a really nice lad. Used to get on with football; an Aston Villa supporter, which was fine by me. He’s a really nice lad, and still is, no doubt. At that stage, and indeed all the while I was involved with Tony, which was probably to about ’74 or something like that, they were just normal lads. Actually I take that back. You can’t actually ever call Ozzy normal. But the other three were just normal lads; they were nice guys. There was never anything overtly weird about Geezer. He was the best bass player I’d ever seen in my life! I’d never seen anybody groove like him, and I think in the initial days—Tony is obviously a terrific musician—but in the initial days, I think the power came from Geezer.”

“Well, I’m sure it’s all true,” muses Bill, addressing the same topic, whether Geezer was into the occult and, for that matter, whether he had actually painted his bedroom back home entirely black and orange. “I don’t remember going to his black room, but you know, I mean, he’s got no reason to lie or anything. He’s a weirdo anyway. They’re all weirdos. We have to establish that from the very beginning. But that’s where all the love is. We love each other because we’re all not quite there, you know? So yeah, there are all kinds of things, all kinds of idiosyncrasies and strange things, that makeup of whatever it is.”

Explore this more with Bill, and you figure there’s a pretty good chance that the evil stuff literally began with no more than the name of the band (or the song) and then blossomed from there. “Well, the name, Black Sabbath, Terry…that’s Geezer, Terry got that from the movie by Boris Karloff. So when we had written ‘Black Sabbath,’ we were still the band Earth. And when we were showing up to play ‘Black Sabbath’ as the band Earth, there was another band called Earth that was showing up as well, and they were playing popular songs and they were I guess putting on a very professional show [laughs], and they were nothing like these scruffy people from Aston. So we had to change our name from Earth, and Geezer had suggested using the name Black Sabbath for the band’s name, and I think that happened when we were crossing from Dover to Dunkirk on the English Channel—he came up with that idea and we went, ‘Yeah, that’s it, good, we’ve got it.’ We had made the song ‘Black Sabbath’ first, and then Geezer suggested, ‘Let’s just call it Black Sabbath.’ We had already named the song after the movie.

“All of us were interested. Just like a lot of people when they’re growing up, they become interested in all that and Black Sabbath was no exception to that,” continues Ward. “So we were interested in scary movies, and it was observant. I mean Tony and Geezer in particular, they were very observant of and aware that people liked scary stuff. So I don’t know how much went into a contrived effort to make scary music. What was actually real in those first few songs that we did…in other words, the difference between organic and commercial. I always like to feel that those things came out of it naturally and exactly as they were supposed to be. But I know that those ideas of making something scary, I know that was something that was bantered around. But at the same time, we were all looking into other aspects of the supernatural or God or religion or anything else for that matter. We were kicking the tires on everything, checking everything out.”

Adds Ozzy, “Why we got to be called Black Sabbath and why it was very dark, we used to rehearse early in the morning in a civic center. And across the street was a movie theater and it was Geezer or Tony that said, ‘Don’t you find it strange that there’s a horror film and people are paying money to get scared? Why don’t we start writing scary music?’ And we poor kids thought that was great. We didn’t realize that there were people that practiced black magic and all that. But Black Sabbath was not all about Satan. We wrote about things that people were thinking but not really talking about. Now they are talking about global warming. We were talking about wars and its effect on mankind. Geezer was a phenomenal lyricist—he still is.”

And then came the music side of it: heavy metal. “Right, well, it’s that place inside,” says Bill, searching. “It’s called primal scream. And all of us wanted to go there. As a drummer, there’s nothing better than playing drums in Black Sabbath, as far as I’m concerned. And in every song I could go to the primal scream inside me. I had to go to that place where you let go of everything, all your anger, all your frustration, everything of the day, and you place it on your cymbals, you place it on your snare, you put it in your bass drum. It’s actually the best, for me, it was the best way of staying well. You know, they called me the quiet guy in the band [laughs], but that’s because I was kicking the crap out of a drum kit every night, and after that I was just real mellow. So that’s how that one kind of works. But yeah, with the way that we were playing, and the things we liked to go to, which again were all of the dark notes, you know, the flat fifths, all of the other discordant-sounding notes. When Tony would go there, it would be…to me, that was like Valhalla. It was like, oh my God, that’s great. And to Geezer and Ozzy as well. I mean, we all loved it. So that would be us kind of steering away a little bit from jazz? Because we wanted to go to that primal scream place, that place where we go, ‘Yeah, you bastards!’ You wanted to go there, but you’re just at that point of absolute laying in. That’s the only way I could describe it. Pure anger.”

Asked how the works of Deep Purple or Uriah Heep at time compared to what Sabbath were doing, Bill figures, “Well, everybody had heavy bits of music. However, if you look at the whole picture with Sabbath lyrically as well, then it becomes completely different. And there were no other bands at the time that were sounding, or were putting the lyrical content into the songs that we were. And we were on our own. I mean, the big hit was friends of ours, Led Zeppelin. They hit enormously and are such a great band, a phenomenal-sounding band. But—and this is no disrespect to Robert Plant; I’ve known Robert for years and years and years and I have no intention of saying something now that would upset him—but the bottom line was that Robert’s lyrics were a little more about, oh, you know, more about falling in love or boy/girl lyrics, type of thing. Which I think he did it his own way, in a very unique way, whereas the lyrics that Black Sabbath performed to were, ‘Figure in black,’ ‘What is this that stands before me?,’ ‘My name is Lucifer,’ you know, so we had very poignant attitudes and were bringing in a very definitive statement about what we really liked and what we liked to play to.”

Same question I asked Jim was now put to Bill: where does that specific heavy metal cliché, the staccato machine-gun riffing of “Paranoid” and “Communication Breakdown” come from in Tony’s past axe education?

“I’ve got no idea,” answers Bill. “With ‘Symptom of the Universe,’ he literally made that famous, that idea. Most of the bands that you hear today will use that same machine-gun feel, and that’s how he saw it and that’s how he heard it, and so he wanted to open up ‘Symptom of the Universe’ with that. And it’s like, ‘Fucking ’ell, let’s go, guys.’ I mean, Terry and I had no problem in tucking into that. We were on top of that literally within a shadow’s breath. Just opened it up, played it, and it’s like, we’re on it.”

And on the subject of heavy metal characteristics, there’s also this idea of quiet/loud whisper to roar, darkness needing light to be defined as the opposite thereof.…“Well, we liked to play soft things. Tony is a very accomplished classical player as well. So you know, it was nothing that was pre–worked out. I’m looking for the word but I can’t find it, but we always loved that. Originally some of those spots came about because when you’re doing a live show and you’re kicking ass for two hours or two and a half hours onstage, as it was in the early days, you need to take a break. And somebody has to do something when you’re getting your breath back and you’re drinking water. You’ve got to get your energy restored. And so Tony would often come up and play a little bit of classic stuff, and so it came in as a useful piece like that.

“Also, it was really nice to hear Tony show off. And I don’t mean show off in a bigheaded way, but it was to show off that part of him, and to us that was a completely natural way of really developing things. I think there were other lead guitar players at the time. I know Jimmy Page would do a lot of that stuff. But Jimmy and Tony were not in the same boat. Nobody was stealing from each other; it was nothing like that. I think what you’ve got is two very individual lead guitar players who just like to play those things. Also there’s Ritchie Blackmore, there’s a lot of guys, even Hendrix himself—it was just a natural part of being able to play that. I think you brought up a really good point there, because when I listen today, to a lot of the bands that I enjoy, a lot of them start out with a lot of the slow melodic things. And when I listen to just the arpeggio of it all, when I’m listening, I’m reminded, I go right back to ’69 or ’68, and it’s a great feeling, because a swell of good memories comes up. And it reminds me of October and November and December in those early years, ’68, ’69, of these wonderful guitar parts, crescendos, that were so part of heavy metal. And it’s a wonderful feeling. It’s a good point that you would notice that and bring that up. I think going back to that rat-a-tat-tat, we better give Jimi Hendrix some credit as well.

Housed within Tony’s extended solo spots over the years were the seeds of many a potential riff on which to hang a potential new Sabbath song.

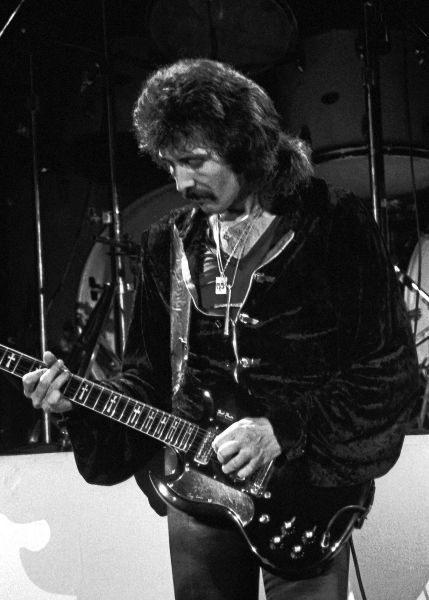

Photo by Ben Upham

“And definitely Cream,” adds Bill, “but also the Kinks, which Ozzy points out very, very well. When Dave Davies played ‘You Really Got Me’ on that burnt-out amp, and man, I tell you what, that sound, it was like, ‘Oh my God—what is that sound?!’ That sound was great, and it just lands…it just puts itself to that really rough edge. Plus the things that the Who were doing, and yes, Cream—when they got together, my God, plus Jack Bruce allowed every other bass player to go wherever they wanted. Jack, you know, I know Jack and I worked with Jack, and he’s just like…he’s just such a lovely man, and he’s totally righteous as a bass player. So, you know, you have a lot of people to thank here. In Hendrix, Mitch Mitchell was playing jazz as well as hard rock. He played everything, but wherever Jimi went, Mitch went. And Noel Redding, he played that kind of free bass thing, which we hear so often in hard-core music. But of course, I know that [John] Entwistle was, to me, the ultimate bass player, and the only exception for me would’ve been Jack—these were great bass players. And so when Geezer showed up, he started playing rhythm guitar [laughs], but then he changed to bass. And when he played bass, he was just like all over the place. He was just everywhere, and when we listen to Sabs, everybody is playing whatever they want to play, really [laughs]. Everybody is playing a lead instrument.

“I don’t know,” reflects Bill, closing on a sociocultural note. “I think the way that music was going, in this almost kind of, ‘Everything is going to be okay; all you need is to have love,’ and things like that, and again I have to say, categorically, that is not a slam on the Beatles. They’re one of my favorite all-time bands. I love them; I love ‘All You Need Is Love.’ But when the songs were coming out, it wasn’t like that for us in Birmingham. And I think the songs were coming out…they were very good songs, but even the Beatles weren’t living in Liverpool anymore. A lot of bands had moved to London, but poverty still existed, and crime still existed, and verbal abuse still existed. And not only Liverpool, but in a lot of the cities, Newcastle, Manchester, tough cities, you know? It was nice, the idea of peace, man, and wearing flowers in your hair, but the reality was, if you looked the wrong way on the streets where I came from, you’d get beaten to a pulp. That’s the reality. So that’s where all the emotional stuff comes in. That’s where it’s like the ‘Fuck you’ comes in. And there was a lot of ‘Fuck you.’ And why there was a desire for us to play loud in Birmingham and why we just made these, almost like violent gestures in our music and in our live appearances, that was us. I think that was literally just reflecting where we were brought up. There may be more from a psychological point of view, but on the surface, I think that’s what you’re seeing—that’s what we’re getting at here.”