4

“Bonham and Ozzy Used to Be the Loudest Two”

A Chat with Norman Hood

Norman Hood is an industry legend around Birmingham, having booked every fledgling band through his Pokey Hole pub on the outskirts of Birmingham through the late ’60s and the very early part of the ’70s, including Earth and Black Sabbath, the latter announcing their name change from the former, on Norman’s small stage. Norman also worked a bit with the boys on the side, as well as with Jim Simpson; he eventually went into business with Tony Iommi and Ten Years After drummer Ric Lee.

What’s perhaps more interesting than the mere fact that Tony was one of three gents in a management stable with Norman is that the small gathering of bands under the IMA domain, quaint businesses that they were, did as much for Birmingham’s reputation as a hard rock town than the bigger flash evidence we all know about, namely Sabbath, maybe Trapeze (not even a Birmingham act per se), and a couple of future Led Zeppelin guys (one of them, Planty, not even heavy yet!).

“IMA evolved from an agency I used to run called Tramp,” explains Norman, “which originally handled Judas Priest, quite a way back. My first involvement, really, was back in 1967, or ’66, really. I was barely out of nappies then, but I got in the blues rock, as it was then, by following Cream and John Mayall and people like that. Then I was on my own again, probably be about ’67, which sort of evolved into Fleetwood Mac. I had a dabble with the music business with what eventually became the formation of Fleetwood Mac, so I’d met a few reasonably well-known musicians before then and got the urge to open a little club with a couple friends. I was booking the bands in from Jim Simpson; his agency in Birmingham, Big Bear, was providing people like Sabbath and Indian Summer, Tea & Symphony, that sort of thing. Right from the early parts of my involvement with Sabbath as Earth, I was booking them through Jim Simpson.

“Mother’s was slightly later,” Hood continues, painting a picture of the Birmingham music scene as it existed at the time of Sabbath’s birth. “Henry’s Blues House was Jim Simpson’s own club, and it was really the club in the center of Birmingham. Jim’s place was originally a blues and blues rock venue. Mother’s was slightly more…I was going to say poppy but that’s the wrong word—it wasn’t quite as blues-based. It was a terrific club, a great big space above a carpet shop, if I remember. And it became probably the better known of the two. But Henry’s was always the basic club. As mine was, it was just a room over a pub, and I mean, there had been clubs in Birmingham before that, but they mainly dealt with touring American blues artists and that sort of thing.”

Henry’s was above a pub called the Crown. Pokey Hole was on Frog Lane in Lichfield, above Robin Hood Public House, in Lichfield, north of Birmingham.

“Yeah, we were about fifteen miles, I suppose, from central Birmingham,” says Norman. “So we did get a certain amount of the Birmingham crowd as well. And of course a lot of our people went into Birmingham quite often. We were Friday night, just a weekly thing on Friday night, which is the worst possible night to run a club because everybody’s got gigs on a Friday night. But Earth, and then Sabbath, used to play for us when they weren’t working. They’d get sort of fifteen pounds at that time. So I used to get them really cheap, but they always filled the club and they always got a good reception.

“There’s a lot of theories,” laughs Norman, asked why Birmingham spawned so much hard-hitting rock music. “Birmingham is a very industrial area, and heavy industry at that—a lot of metalworking. It’s the Black Country, so by its very name, there’s a lot of foundries there, a lot of heavy industry. And I think people immediately thought that it was a reflection of the area. But I think a lot of the bands that came up in the Birmingham area were copycat Sabbath, really. I think Sabbath and Zeppelin were the two headliners, and I think so many bands saw them locally that their music was influenced more by Sabbath and Zep than by their surroundings. So it’s difficult to explain. Birmingham was a sort of doom-laden, smoke-covered, soot-blackened place, but it’s not that bad, really [laughs].”

Sometimes, as outsiders, we’re guilty of pushing the Zeppelin connection too far. After all, Robert and the Band of Joy material…it was fairly folk, blues, and psych-y, not exactly proto-metal. Plus, of course, the seed heaviness of Zeppelin comes from Jimmy Page and a London band called the Yardbirds. Still, John Bonham had a reputation as a loud drummer (according to Glenn Hughes and Carmine Appice), helping to promote bashing by wanting his drums closer to the front of the stage, and even requesting that his name be added to notices of his band’s live gigs.

“Not to my knowledge,” reflects Norman, on that last crumpet of trivia. “I must say, I only met him socially. Saw him onstage a few times obviously, but I didn’t get any impression of that at all. The only rifts that I ever came across were of course in Sabbath, because really, Ozzy was getting a bit too hard to control, but otherwise, you know, it was all very placid. Bonham was in the Keith Moon mold, and having met both of them, I’m not sure which was the crazier. When we got offices in Birmingham, we used to get the Zeppelin lads in there quite a lot, as well as Sabbath. It was always…Bonham and Ozzy used to usually be the loudest two, probably within sort of ten miles. Yeah, he was unfailingly polite, a really nice guy. Didn’t have a speck of trouble with him. Never worked with him, obviously, because by then they were a major band. But yeah, he was loud. Definitely loud.”

Further underscoring Birmingham’s reputation for new flash rock music were Slade and Trapeze. Slade were soon to be classed as more of a British glitter band, but nonetheless were heavy rockers for the day. Trapeze, featuring future Sabbath singer and Iommi collaborator Glenn Hughes, started out folky, perhaps reflecting their signing with Moody Blues offshoot imprint Threshold. But by the second album, Medusa, issued in November of 1970, Trapeze were rocking quite hard.

“Met the Trapeze guys quite early,” notes Norman. “They were run out of Wolverhampton, which, I suppose, you can put as a suburb of Birmingham. They were run by an agency who, in a sense, were rivals. They were probably bigger than my little agency, and better, more than likely, so really they were run by a rival agency. Slade, obviously, I love Noddy [Holder] to pieces [laughs], but again, they were just slightly out of town. They weren’t classed as a Birmingham band, if you like; they were Wolverhampton, as were Trapeze. So they didn’t really come into our radar.”

And before all this hard rock business, Birmingham had a rich legacy of blues and jazz, did it not? “Absolutely, yes. The Birmingham International Jazz Festival was actually started by Jim Simpson, and I worked with him on it for quite a few years, and it’s still going. Not quite as star-studded as it was. I mean, we used to have people like Basie and Buddy Rich and some real big names at the festival. But there’s always been a lot of jazz clubs—still are. There was even a Ronnie Scott’s in Birmingham for a while, which I think now is a pole-dancing club. So yeah, it’s quite a legacy of music.

“A lot of the British blues bands got into a heavier sound themselves,” says Hood, asked if this new music was emerging because the British blues boom was burning itself out on predictability and way too many bands on the bandwagon. “I think a lot of bands did get heavier. Not as far as being classed as metal, that heavy, but eventually yeah, they definitely got louder and a little heavier with their music.”

I asked Norman what Birmingham’s relationship was to the bands, fans, and industry people in London.

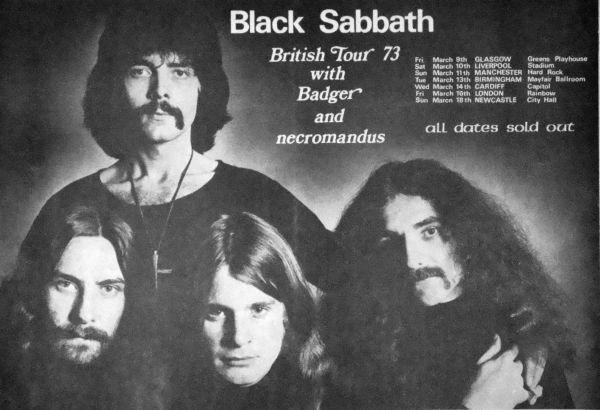

Double-page print spread for the band’s spring 1973 tour of the UK. Cumbria-based backup act Necromandus (managed by Tony Iommi) never managed to get a record out, despite substantive initial buzz.

“I don’t know that there was any sort of bad feeling. For example, Sabbath…I don’t think that London knew quite what was going on for a while because of the underground nature in which Sabbath rose to prominence. In other words, the fact that they worked right the way around the country and built up a following…I think the London press, certainly, seemed to think that they had suddenly just popped up overnight, but the actual music fans knew all about them. So when the first Sabbath album was released and then went to whatever it was, #2 or #4 or something, that was on the back of working every night of the week, all around the country. So it was a surprise to the London press but not to music fans.”

It was in this environment that Norman, Ric, and Tony put together IMA, first conceived given Tony’s interest in the band that eventually became Necromandus.

“Sabbath had stayed up in Cumbria for a while, Whitehaven,” explains Norman, “working from that area before, I think, the formation of Earth. Tony and the band had got links to that area, and one of the bands that they knew, or that had been formed after Sabbath had been formed, got in touch with me from Whitehaven and sent me some tapes. And Tony was really enthusiastic about managing them himself and taking them on as far as he could. Sabbath were going pretty well, and I think he thought that it would be just a nice thing to do, a hobby, maybe, to look after this band. They had got some horrible name at the time, Hot Spring Water or something. Tony and I agreed that we’d form a little management company, a little agency. IMA was what resulted from it. Although a lot of accounts I’ve seen have thought the I stood for ‘Iommi’, it never did. I think it was International Management Agency or something, something very flash for those days. The holding company was called Pactmoor, and Pactmoor were the ones who signed Judas Priest. That sounds very involved—I hope you can piece it together [laughs]. Anyway, when that band first got in touch with me by letter, it was called Hot Spring Water. Yeah, exactly [laughs]. Well, that didn’t last long. I think for a small period of time they were called Taurus. Again, that was a bit anonymous, so eventually they came up with Necromandus, and they were one of the main bands we were handling at that time.”

And why didn’t IMA figure in the management of Black Sabbath itself?

Along with the infamy of being the heaviest band on the planet come endorsement deals.

“We were never in a position to do that,” says Norman. “And for the same sort of reasons that Jim probably couldn’t have taken them much further. They needed to be handled by the big boys, if you like, or at least the London people who knew, really, how to take them on to that next level. I think even Jim came to realize that eventually. I know he was quite bitter about it for quite a while, and probably still is. It’s difficult and I can see both sides. At that stage, I was getting pretty friendly with Tony. We used to knock around together for a few years around that time, and it was acrimonious. I knew Jim pretty well, obviously. I was pretty good mates with Tony, so basically I sat on my fence. As I say, I could see both sides of it. I could appreciate Jim put a lot of work, a lot of effort, into the band, and probably without him they would never have built up the grassroots following that eventually took them onto fame, if you like. I could also see from the band’s point of view that he’d probably taken them as far as he could. At that time the music business was very London-centric. We were out in Birmingham—although the distance from over your side of the pond is like next to nothing, 120 miles over here in the ’60s was a long way, and everything tended to be centered on London. And the band obviously soon started making waves and making money and making records and they were a prime target for the sharks in London. And to be fair, I wouldn’t have tried to get on the inside because I just couldn’t be helpful. They needed professional management and I was far from that. I was quite happy just to sort of tag along and go into the studio with them and do the odd gig with them. It was nice.

“Again, not really qualified to comment on that,” continues Norman, asked to assess the strengths and weaknesses of Sabbath’s new manager, Patrick Meehan Sr. “I met him, Patrick Meehan, and Wilf Pine. I probably know Wilf better; he was really friendly to me. They knew that I was in a slightly strange position, but because I was a friend of Tony’s they were always unfailingly polite. But as far as the business goes, I just turned around and right glad I did because those were quite big boys to play with. Wilf was a nice chap. I knew his reputation, but the couple of times I met him, he was unfailingly pleasant. A lot more so than one or two of the other agents around at that time who I was always very careful to keep well away from.

“He was generally happy,” opines Norman, asked if Tony had at all been letting on that things weren’t as financially square in the Sabbath camp as appearances might have portrayed. “I mean, there are always gripes, obviously, and the grass is always greener. Again, as an outsider, I wasn’t privy to any of the dealings with the band. I met the guys at Worldwide, I met David Hemmings and people like that, and they were all really nice fellows, but I was very much on the outside. From listening to it, Tony and Geezer probably were the ones who were more business-orientated. They weren’t particularly happy at the cut they were paying. I mean, it’s all the same, isn’t it? You go to somebody new and they seem terrific for a while, but after a while you start begrudging them the money. When you’re making a lot of money, the cut that they’re getting seems to be a lot as well. So I don’t know.”

A band with an almost comically fluid lineup called Judas Priest turned out to be the anchor of IMA’s modest stable. “I think we signed them formally with the agency in ’73,” recalls Hood. “They had been under my wing for a while earlier on, probably I would think from about ’69, ’70, something like that. I used to work with a guy called Dave Corke who was really the driving force behind Judas. We worked together for quite a while. But Priest, we had a friendship that stayed right through until they got big and I decided I was never going to make any money off it. But Priest were far enough behind Sabbath to be influenced by them. I suppose when I first got into them, or they first got into it through me, rather, they’d only got two of the members, obviously, just Ken Downing and Ian Hill.”

It’s interesting, though, that Priest actually had roots back to 1969. It becomes lost in translation that by the time Priest issued their debut album, Rocka Rolla, in 1974, sure, Sabbath had fully five albums out, but the roots of both bands are essentially a year apart, meaning that original metal was being forged at essentially the same time. Still, Sabbath bulldozes o’er any influence of Priest, really, with respect to the invention of metal, through those first five albums, while Priest fussed about with lineup switches and a mere handful of originals, as good and modern and metallic as these early compositions were.

Norman was around to witness that switch in the vocalist position from Al Atkins to Rob Halford. “Al swears that I sacked him, but that’s not true at all,” reflects Hood. “I wouldn’t ever do anything like that. It was a band decision, really. I’d had very little dealing with Rob Halford. I knew of him; he was in a band called Athens Wood that had been in touch with me and I’d seen them a couple times. But it was a band choice—definitely not me. I have told Al that, but I think he likes telling people I sacked him. Again, the chronology of it…everything happens so quickly. I mean, I was only involved from Fleetwood Mac through to deciding that doing a brewery is what I was cut out for—that was about eight or nine years. So it all happened very, very quickly. IMA, as you know, was three people: myself, Tony, and Ric Lee, who, again, was the drummer for Ten Years After, who obviously, they stormed at Woodstock, so they were also pretty well known as well. And because of that and because of the fact we were based in Birmingham, we pretty much had our pick of the local bands. But eventually it came down to Necromandus and to Judas Priest. I was really responsible for Necromandus, and Dave Corke, who again was working for me at this stage, he was Judas Priest through and through; so he looked after them. But really, he was the one that believed in them.

“For a start, they were never my favorite band,” continues Hood, with respect to the Priest. “When we first took them on I was very, very doubtful about whether they would actually be able to make it. Maybe they were trying to be a little too close to Sabbath, I don’t know. But there was no doubt that Ken was an amazing guitarist. I think when they took Glenn Tipton in, that was really what actually made them different, took them apart, lifted them out of the sort of support band role. I think the twin guitar thing, although it had been done before, obviously with people like Wishbone Ash, what have you, I think Ken was a heavy rock guitarist and Glenn was a rock ’n’ roller. The Flying Hat Band, which were also one of the agency bands at that time, they were great rock ’n’ roll, but I think Priest just jelled; they really did. They still owe me seven hundred quid, by the way [laughs].

“Probably not that close, honestly,” is Norman’s assessment of how near the Flying Hat Band were to getting a record deal. “Flying Hat Band was Glenn. As I say, in live performances they could actually get a room up and bombing about. They had no trouble packing them out. They were a very popular club band. Whether they could have actually made a successful career on the back of that, I don’t know. I’m not entirely sure. I think they would have probably been an average rock ’n’ roll band, which is probably what the record company thought as well.”

Black Sabbath: Part of a complete and hearty English breakfast.

As to Necromandus ultimately fizzling, “I think it was timing. While Tony was their manager, he was attracting a lot of attention to them because people thought that if they booked Necromandus then next week they could have Sabbath, but of course that wasn’t the case at all. Sabbath by this time were taking off really, really big. They recorded the album and everything was all set to go; it was all sorts of systems go. And then I think, basically, Sabbath hit big in the States, just at the wrong time. Tony disappeared; there was delay after delay with the album. I think Baz Dunnery got a little bit fed up and he wanted things to move faster than they were. They were stuck on a level of gigs that weren’t actually paying them enough. I mean, they were struggling, and I don’t think they were quite able to get out of that. They weren’t able to move up without the impetus of Tony behind them. At this stage, Tony had got other things on his mind.

“It was getting to the stage where my involvement started getting less and less with them,” says Norman, in closing. “I packed it in in ’76, I suppose, but by then I’d gone back with Jim, because of Tony and going across to the States. Ric Lee had fallen out of the company quite early because he was about the only person that managed to lose money in the property boom going on around at that time, and decided that he wanted to concentrate on his property. Tony then disappeared to the States, and gradually the whole thing sort of wound down. So by about ’74, I was back working with Jim and bringing American blues artists over to tour over here, which was rather close to my heart—the old blues [laughs].”