( 8 )

PERFECTING SOVEREIGN

TITLES, 1900—38

The nineteenth century belonged to the United States; the twentieth century belongs to Canada.

PRIME MINISTER WILFRID LAURIER, May 19021

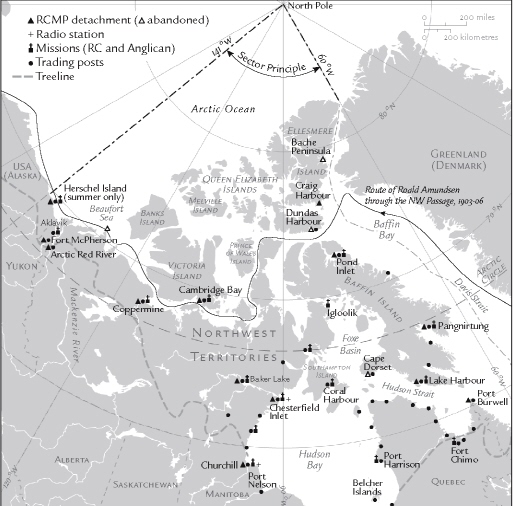

PRIME MINISTER Laurier’s oft-quoted statement was little more than a promise in 1902, but it reflected Canadians’ optimism and the determination of Liberal politicians to stand their ground in a world of imperial ambitions. The quotation is even more apt when applied to Arctic Canada, which had been under continual threat in the nineteenth century, either by American explorers searching for unmapped islands, by whalers establishing permanent stations in Canadian territory or by wild political schemes of encircling Canada through the purchase of Greenland. Yet within thirty-odd years, Canada not only secured sovereign title to the Arctic Islands but in the process appeared to have developed a strategy to deal with future conflicts.

During the same period, Denmark faced an official challenge by Norway over rights to East Greenland. The issue was eventually settled by the Permanent Court of International Justice, but not before Canada and Denmark had agreed to support each other’s claims to Arctic sovereignty, setting a precedent that later evolved into cooperation between circumpolar countries to defend their rights against more powerful nations. With the exception of the Svalbard Islands, the Soviet Union by decree in 1926 claimed sovereignty over all islands between its mainland and the North Pole, in the sector bounded by meridians 168° 49' 30" W and 32° 49' 30" E, in accordance with the policy set out in 1916 by the imperial Russian government, a claim that has never been officially challenged in the courts.2

At the turn of the century, Canadian claims to portions of the Arctic still appeared vulnerable, partly because of the vague terms describing the lands Britain had transferred in 1880, but also because of the tension between Canada and the United States over the Alaska Boundary Dispute, the collapse of the Joint High Commission in 1899 and in 1901 the rise of Theodore Roosevelt to the presidency following the assassination of President McKinley. A less tangible factor, but nonetheless a concern, was Britain’s tendency to prioritize friendly Anglo-American relations ahead of Canadian interests. Yet the character of the Canadian government had changed considerably from earlier years. Following the Liberal victory in 1896, Prime Minister Laurier filled the cabinet with men of talent and experience, many of them lawyers. Moreover, his first term in office coincided with a return of economic prosperity which, when coupled with the government’s apparent success in managing the Yukon gold rush, inspired a sense of confidence among Canadians in the future of their country. Strong sentiments of Canadian nationalism were emerging, but as Robert Craig Brown and Ramsay Cook have argued, it was still driven by a “fear of the real or imagined potential of the United States to absorb Canada.” 3

Laurier’s appointment of Clifford Sifton—a lawyer and former attorney general of Manitoba— as minister of the interior guaranteed Canada a strong defence of its boundary rights and appropriate governance for the new territories. Also important was the appointment as minister of justice of Senator David Mills, a seasoned parliamentarian with professional expertise in constitutional and international law. Along with others such as W.S. Fielding, A.G. Blair, J.I. Tarte and Sir L.H. Davies, Laurier’s cabinet provided the support and advice necessary for the government to devise a clear plan of action to defend Canadian claims to Arctic sovereignty without provoking official protest from the U.S. Laurier also had the backing of most Canadians, who supported a firm stand against overt or implied threats to Canada’s sovereign authority.

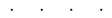

Sir Wilfrid Laurier, prime minister of Canada, 1896 –1911. Laurier’s first term in office coincided with a return of economic prosperity, which inspired a sense of confidence among Canadians in the future of their country. Laurier may have had suspicions of American motives in Alaska and doubts about British support, but he voiced them with diplomatic caution.

LAC, C-000688

Laurier and Sifton may have been of one mind in their objectives, but the two men sometimes differed as to appropriate action. Laurier suspected American motives in Alaska and had doubts about British support, but he voiced them with diplomatic caution. Sifton was younger, often outspoken in his anti-American views and distrust of the British, but, like Laurier, he believed it best to protect Canadian rights by preventive action before a problem arose. Not surprisingly, Sifton was already laying plans to assert Canada’s authority in the Arctic long before the Alaska boundary dispute had been settled. Nor was he alone in his concerns. In the North-West Mounted Police’s Annual Report of 1901, Commissioner A. Bowen Perry repeated the warnings of his predecessors and called for police supervision in the eastern and western Arctic. Referring to reports of lawlessness, he argued that “the cost of carrying law and order into the Arctic regions may cause hesitation, but when our territory is being violated and our people oppressed, cost should be the last consideration.” 4 Plans to build a police post on the Mackenzie River the following year were deferred because of a rumoured miners’ revolt in the Yukon, but not abandoned.

Clifford Sifton, minister of the interior, 1896–1905. Unlike Laurier, Sifton tended to be outspoken and impetuous, a characteristic that was largely responsible for the Canadian government’s swift action to protect its sovereign authority in the Yukon and the Arctic.

LAC, PA-027942, Topley Studios

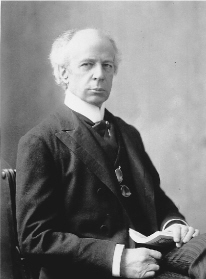

Meantime, several foreign explorations had taken place in the Arctic Islands. In 1902, Robert Peary, a former U.S. naval officer, returned from yet another expedition, this time involving mapping northern Ellesmere Island, still referred to as Grant Land on American maps. That same year, news reached Ottawa about a four-year expedition led by Norwegian Otto Sverdrup that centred on Ellesmere Island. Further west, he discovered three new islands, which he named Ellef Ringnes, Amund Ringnes and Axel Heiberg after the beer companies that had funded his explorations. Unknown to the Canadian government, Sverdrup’s submission to the Swedish king requesting that his work be accepted as a national claim was ignored, as was a second request to the Norwegian government following separation of the two Scandinavian countries. Yet in the Canadian view, there always remained the possibility that Norway might attempt to claim the three islands. Rumours also reached Ottawa that yet another Norwegian explorer, Roald Amundsen, was planning to traverse the Northwest Passage.5

SVERDRUP’S EXPLORATIONS IN THE ARCTIC ISLANDS, 1898–1902

Explorations by Norwegian Otto Sverdrup and his party covered areas which much later were found to have major oil and gas fields. At the time, the King of Norway expressed little interest in claiming title to the lands by right of discovery because of their remote location and the assumption that they were of little value.

Then in the fall of 1902, Sifton received a report co-authored by Comptroller Fred White of the NWMP, Commissioner McDougald of the Customs Department and Robert Bell of the Geological Survey, calling for the government to take immediate steps to assert its authority in the Arctic. In response, Sifton authorized two expeditions under the auspices of the Department of Marine and Fisheries, with the intent of establishing police posts in the western and eastern Arctic.6

By then, Laurier had realized that it would be necessary to settle the Alaska boundary dispute before trade agreements and other matters could be resolved with Britain and the U.S. Thus, with the consent of the Canadian government, the Hay-Herbert Treaty creating the Alaska Boundary Tribunal was signed on 24 January 1903 by the U.S. secretary of state and the British ambassador in Washington. The tribunal was to be held in London and made up of six “impartial” judges, three appointed by the U.S. president and three by “His Britannic Majesty.” Although two of the latter were Canadian, the process reflected the lack of control Canada had over the situation and its foreign affairs. Sifton was irate. In a personal letter he claimed that the British government had decided “to sacrifice our interests at any cost for the sake of pleasing the United States.” Reflecting genuine despair, he suggested that “whatever the United States demands from England will be conceded in the long run, and the Canadian people might as well make up their minds to that now.” 7 Yet with revitalized tenacity, Sifton continued to defend Canadian sovereign rights, against friend and foe, real or imagined.

Norman Penlington, in Canada and Imperialism, argues that English Canadians had difficulty understanding, much less accepting, that Britain would support Canadian interests only if they did not adversely affect Anglo-American relations. Nor did they realize that “Britain’s very existence in the twentieth century was to depend on the benevolent neutrality and friendly assistance of the United States.” Yet Canada was also dependent on the United States—initially economically and later militarily—a factor that Penlington believed contributed to the country’s ambiguity and weakened Canadian nationalism.8 At the turn of the century, however, the triangle relationship had not yet matured. Instead an acute sensitivity emerged, particularly among anglophone Canadians, to any perceived threat to the nation’s sovereign rights, a sensitivity that flourished with growing recognition of Canada’s unique identity as a northern nation. In time, the Arctic became the ultima Thule of the Canadian North and would be celebrated in Canadian art and literature.9

Members and advisers of the Alaska Boundary Tribunal, held at the Foreign Office in London, October 1903. The six judges (unnamed)—two from Canada, three from the U.S. and one from Britain— are sitting on a raised podium at the rear of the photograph, with delegates and legal advisers in front. The British judge sided with the Americans against the Canadian claim, sparking angry protests in Canadian newspapers against both Britain and the United States.

LAC, C-021425

Although Canada’s claims in the Alaska boundary dispute were tenuous at best, the popular press stirred up strong anti-American sentiment in advance of the tribunal, charging that the U.S. was trying to steal land that rightfully belonged to Canada. American newspapers were equally persuasive in portraying “British” Canadians as villains. To make matters worse, President Theodore Roosevelt ignored the impartial criteria and appointed his secretary of war and two senators as judges, all with vested interests in an advancing American claims. As Laurier anticipated, Britain did not protest the appointments. To ensure that the Canadian argument was presented in the best possible light, Laurier appointed Sifton to head the legal delegation, which included Joseph Pope, who later became Canada’s first under-secretary of state for external affairs, and chief astronomer Dr. W.F. King, by then a respected authority on sovereignty issues. Should Canada lose the case, Laurier was determined that no blame would fall on the legal team or his government. En route to London, however, Sifton became increasingly concerned about Canada’s claims elsewhere in the Arctic after discussion with King and requested that he prepare a “thorough and complete” report on Canada’s title to the Arctic Islands.10

Before leaving for London, Sifton had left precise instructions for his deputy minister to obtain prior approval from opposition members to ensure the appropriation bill for the new police detachments was passed by Parliament as quickly and quietly as possible. He also prepared an innocuous press release to avoid embarrassing questions concerning the purpose of the two expeditions. As planned, funding for them was expedited through Parliament in his absence, with the result that they departed without fanfare, each accompanied by six mounted policemen. As a result, two NWMP detachments were established and staffed in the summer of 1903, one at Fort McPherson on the Mackenzie River and the other at Fullerton Harbour on Hudson Bay. Police from the Fort MacPherson detachment would visit Herschel Island that summer to ensure that American whalers knew they were in Canadian territory and were required to comply with the country’s laws and customs regulations.11 After their success in the Yukon, the NWMP were thought to be the most effective means to maintain sovereignty in areas occupied by Americans. They were also responsible for a variety of administrative tasks such as postal service, issuing of licences and collecting customs duties, which provided evidence of “effective occupation.”

The expedition to the eastern Arctic had an additional mandate. Albert Peter Low of Canada’s Geological Survey commanded the party aboard the chartered SS Neptune, with the full knowledge and assent of Lord Minto, Canada’s governor-general, and presumably that of Britain’s Colonial Office.12 Instructions to Superintendent J.D. Moodie, in charge of the new detachment, indicated that the government’s plan had been carefully designed with a view to expanding the Canadian presence even further. “The Government of Canada having decided that the time has arrived when some system of supervision and control should be established over the coast and islands in the northern part of the Dominion, a vessel has been selected and is now being equipped for the purpose of patrolling, exploring, and establishing the authority of the Government of Canada in the waters and islands of Hudson Bay, and north thereof.” 13

The expedition first sailed to Cumberland Sound to observe whaling activities, then proceeded to Fullerton Harbour, where the party spent the winter and assisted the police in building the detachment. Moodie had also been given clear instructions to avoid “harsh enforcement of the laws” and instead was to give captains of foreign ships fair warning that in the future “laws will be enforced as in other parts of Canada.” 14 That winter only one American whaler—Era—was anchored in Hudson Bay. The next spring, the Neptune dropped Moodie off at Port Burwell; he then made his way south to report to Ottawa.

From Port Burwell, the expedition sailed north along the Greenland coast until reaching Ellesmere Island and the site of Robert Peary’s former camp at Cape Sabine. After a thorough investigation, Low built a cairn at nearby Cape Herschel, raised the flag and took formal possession of Ellesmere Island “in the name of King Edward VII for the Dominion.” 15 The ship then sailed south and westward along Lancaster Sound, stopping at Beechey Island where the crew found recent evidence of a visit by Roald Amundsen, reportedly on his way through the Northwest Passage in his tiny ship Gjoa. Once again the flag was raised, possession declared and a photograph taken of the event. Heading toward Port Leopold on North Somerset Island, Low stopped to investigate what appeared to be a building. On closer examination, a large stash of supplies left for Amundsen was discovered, leaning against a ship’s steam boiler and marked with a Norwegian flag. Low again raised the Union Jack, but this time deposited a proclamation and a copy of Canadian customs regulations in the abandoned boiler.

Returning south, the ship stopped to visit whalers anchored in Eclipse Sound and Cumberland Sound, carried on to Port Burwell for supplies, then headed back to Fullerton Harbour before returning home. Low’s published report, over 300 pages long, finally provided the Canadian government with detailed information about the Arctic Islands, the geology and wildlife, whaling and trading activities, descriptions of Inuit communities and a complete history of previous explorations. As a first priority, Low recommended that a police post be built at Port Burwell near the entrance to Hudson Strait, even though his statistics on American whaling activities indicated a drastic decline. From the government’s perspective, the latter information tempered the urgency to construct more police posts in the area.

Meanwhile, news that the Alaska Boundary Tribunal had rejected Canadian claims spread throughout southern cities and towns. Angry protests in the daily newspapers again fuelled public outrage that helped solidify anti-American sentiment and ended any lingering support for annexation to the U.S. This time, however, anger was also directed toward Britain, as the British judge had sided with the Americans in rejecting Canadian claims. In the House of Commons on 23 October 1903, Laurier attempted to explain the problem by stating that “as long as Canada remains a dependency of the British Crown, the present powers we have are not sufficient for the maintenance of our rights.” 16 As he had hoped, no blame for the decision would be attached to the Canadian judges, the Canadian legal delegation or his government.

Raising the flag at Port Leopold as a symbol of Canada’s sovereign authority. When the expedition led by A.P. Low arrived at Port Leopold on North Somerset Island, they discovered a Norwegian flag flying above an abandoned ship’s boiler and a cache of supplies left by explorer Roald Amundsen, who was attempting to traverse the Northwest Passage by ship.

LAC, PA-050922, Geological Survey of Canada

After receiving Moodie’s initial report recommending seven new police posts and twenty-seven police officers to staff them, Sifton waited for reports from King and Low before making a firm commitment.17 Prime Minister Laurier was moving in a similar direction but cautiously. In the fall of 1903, he explained to Senator W.C. Edwards that his plan was to “quietly assume jurisdiction in all directions,” with police posts along with “a cruiser to patrol the waters and plant our flag at every point.” Only when “we have covered the whole ground and have men stationed everywhere” would he consider a proclamation declaring sovereignty over the entire region. Laurier also believed it important to conduct thorough surveillance in advance of any public declaration, lest there were existing American settlements unknown to the government.18

King’s confidential report in January 1904 prompted immediate action, with Laurier submitting a request for a sum of $200,000 for polar exploration, of which $70,000 would be spent on purchase of a German ship, Gauss, previously used for Antarctic expeditions. The ship was renamed CGS Arctic with Joseph Elzéar Bernier appointed as its captain, the only Canadian to have expressed a keen interest in Arctic exploration. In 1904, under the authority of the Department of Marine and Fisheries, the new government ship returned Moodie and replacement officers to the Fullerton detachment and remained for the winter. The next spring, during a brief reconnaissance of Hudson Bay, the ship’s propeller was damaged by ice, forcing Bernier to return home for repairs and await further instructions. Like Low, Bernier also recommended that a police post be established at Port Burwell, a proposal that first required clarification of the boundary between the Northwest Territories and Labrador/Newfoundland, the latter still held by Britain.19

By now, Sifton and Laurier had had sufficient time to digest King’s final report together with the earlier reports from Moodie and Low. With whaling in both the eastern and western Arctic in decline, concern now centred on foreign explorations taking place in the remote uninhabited islands. On this issue, King’s report was not reassuring. With lengthy explanations concerning the vague boundary definitions and the method of transfer, the chief astronomer blamed Britain directly for apparent weaknesses in the title, arguing that while British claims rested on acts of discovery and possession, they “were never, prior to the transfer to Canada, ratified by state authority, or confirmed by exercise of jurisdiction.” As a result, King argued, “Canada’s assumption of authority in 1895 may not have full international force.” In summary, he suggested that “Canada’s title to some at least of the northern islands is imperfect” but “may possibly be perfected by exercise of jurisdiction where any settlements exist.” 20

A supplementary memo dated 7 May 1904 was somewhat more optimistic, suggesting that British discoveries might have greater legal force because Admiralty explorers were under specific instructions to take possession in the name of the Crown, whereas recent foreign explorations did not have official sanction nor were their claims followed by government ratification. Hence King advised that initial action should centre on locations where Americans were occupying sites in Canadian territory without the authority of their government, in which case Canadian authority could and should be firmly asserted. Otherwise, he believed that Canada had been fortunate that there had been no attempt by foreigners to establish officially sanctioned settlements in Canadian territory, as “occupation” was the most effective means of “perfecting” an inchoate or temporary title claimed through discovery.21

Some of King’s opinions were open to debate, such as the statement that until the passage of the Colonial Boundaries Act in 1895 the Canadian government may not have had the legal authority to deal with the Arctic Islands. This assertion was later refuted by Dominion Archivist Henry Holmden, who based his report in 1921 on recently acquired documents and maps dating back to the transfer. Noting that King did not have access to this material at the time of writing, Holmden acknowledged that the error was understandable.22 Even then, analysis based on existing knowledge of international law was only tentative as legal interpretations varied and generally required a court case to test their validity. Nonetheless, King’s report confirmed that immediate action had to be taken to avoid a challenge to Canada’s title.

Of particular significance was King’s assertion that under “accepted principles of international law, the waters of the northern archipelago and of Hudson Bay and Strait are considered territorial.” Based on that assumption, the Canadian government took the first official action in asserting its authority in Hudson Bay by passing an amendment to the Fisheries Act that imposed a licence fee of fifty dollars for all whalers fishing in Hudson Bay, including Canadian vessels, and in all waters north of 55° N latitude. Upon receiving notice of the new legislation, British authorities expressed concern that it would cause an official protest from the U.S. After reading a detailed report on the Canadian position, Lord Crewe as secretary of state for the colonies wrote to Canada’s governor-general, suggesting that Canada might wish to avoid any action that might lead to tribunal arbitration, which he warned might result in denial of its claims. While Canada claimed Hudson Bay as mare clausum, Crewe suggested that tribunal jurists might narrowly restrict the limits of territorial waters which, he reminded the governor-general, was “an inclination which His Majesty’s Government share on grounds probably well known to your ministers.” 23 Once again, it appeared that Canada was expected to defer to the interests of the mother country. In the end the Colonial Office did not advise disallowance of the legislation, as Crewe had intimated it might, and there was no formal protest from the U.S. government. Instead, licence fees were collected and customs duties paid without difficulty, in spite of a U.S. notice to American whalers to disregard demands for licences.24

Joint British-U.S. survey team mark the Yukon-Alaska boundary at the Arctic Ocean. The surveyor on the left waving a pennant from Princeton University is Thomas Riggs Jr., who later became governor of Alaska Territory (1918–21). On the right is John Davidson Craig, waving a Queen’s University pennant, who was appointed the first commander of Canada’s Eastern Arctic Patrol in 1922 and later Canadian chair of the International Boundary Commission.

Alaska State Library P297-280, Early Prints of Alaska Photograph Collection

Following the decision to defer construction of additional police posts, Captain Bernier was placed in command of three expeditions that took place in 1906–7, 1908–9 and 1910–11, with precise instructions from the Minister of Marine and Fisheries on how and where to take possession of lands by “raising the flag” and leaving a written proclamation in stone cairns. On each voyage, he wintered over on the ship: the first year near present-day Pond Inlet, the second at Winter Harbour on Melville Island and the third in Arctic Bay off Admiralty Inlet. Since Bernier’s expeditions were not accompanied by the police, he was granted permission to perform a variety of administrative functions, such as issuing the new licences and collecting customs duties from foreign whalers. Yet he, too, was warned to be “most careful in all your actions not to take any course which might result in international complications with any foreign country.” 25 On his first expedition in 1906–7, Bernier made fifteen claims of possession, on the second a total of eleven and on his last voyage only eight.26 In each case he took possession for “the Dominion of Canada” with no reference to a British monarch, as was the case in A.P. Low’s proclamations, likely because the instructions had come from Canadian sources without consultation with the British Colonial Office.

Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen and his crew aboard the Gjoa arrive at Nome, Alaska, in August 1906, after successfully traversing the Northwest Passage from east to west and allegedly discovering the magnetic pole.

Alaska State Library P 48-104, Frank H. Nowell Photograph Collection

News that Amundsen had successfully traversed the Northwest Passage raised new concerns about its possible designation as an international strait. Equally disconcerting was the fact that the Norwegian claimed to have charted and named several newly discovered islands. In an attempt to resolve the status of the Northwest Passage and protect Canadian lands against encirclement by foreign claims, in 1907 Senator Pascal Poirier proposed adoption of the Sector Theory to lay claim to all lands north of its mainland.27 Laurier rejected the idea, arguing that the exercise of authority was the only reliable means of protecting title in remote areas. Yet in spite of political implications, boundaries defined by the Sector Theory, or Sector Principle as it is sometimes called, began to appear on Canadian maps and even on the plaque Bernier erected in 1909 on Melville Island. A glance at any circumpolar map shows why the U.S. consistently rejected the principle and why Russia and later the Soviet Union supported it. There were no islands north of Alaska but hundreds north of mainland Canada and Russia.

For the time being, Bernier’s “sovereignty patrols” were considered sufficient evidence of “effective occupation” as long as no foreign country attempted to establish a colony in the area. King’s report had relied on the writings of jurist William Edward Hall for his interpretation of international law, noting in particular Hall’s statement that if “duly annexed and the fact published, or . . . recorded by monuments or inscription on the spot,” such action was sufficient to maintain title, “allowing for accidental circumstances or moderate negligence,” before settlements or “military posts” were established to gain full rights of possession. If no action occurred within a reasonable time, then a temporary or inchoate title claimed by reason of discovery would lapse.28 Although criticized later as inadequate, Bernier’s acts of possession were commensurate with King’s understanding of international law.

To provide further evidence of administrative acts, Bernier had recommended that Parliament pass a game law to protect against indiscriminate hunting, thus providing him with additional government regulations to administer. Laurier agreed but it was too late to secure legislation during that session. Of particular importance at the time had been the proposal to create a separate department to deal with foreign affairs. After intense debate, the bill creating the Department of External Affairs finally passed both houses, received royal assent and took effect on 1 June 1909, with Sir Joseph Pope appointed as the department’s first under-secretary of state. Even then, another three years passed before the new department gained significant power, by way of legislation allowing it to report directly to the prime minister.29 The public appeared to support the idea of gaining more independence from Britain, but only to a degree. Laurier’s plans to build a Canadian navy met with intense ridicule from both the Conservative opposition and the press, which sarcastically labelled it “a tin can navy.” No one will ever know if the prime minister’s plan was simply to deploy a few ships to patrol the eastern Arctic, since the Liberal government went down to defeat in October 1911, abruptly ending Laurier and Sifton’s plans to protect Canada’s Arctic sovereignty. Upon his return home late that month, Bernier tendered his resignation in the knowledge that the new government would likely have other ideas on how Arctic sovereignty should be maintained. Some have suggested that he was asked to resign for having misappropriated government funds for private trade with the Inuit.30

Although Bernier received considerable publicity for his “sovereignty patrols,” it was Sifton and Laurier who proposed them and made them possible. Admittedly Sifton is better known for his promotion of western settlement, but as his biographer D.J. Hall argues, he “can be credited nevertheless with making some of the earliest attempts to establish a credible, continuous Canadian presence in the far north.” Hall also contends that he took a much stronger anti-American stand than the prime minister and that while “Laurier appeared cowed by American bluster and threats, Sifton stood firm in asserting Canadian rights.” Even in later years when chairing the Conservation Commission, Sifton spoke out against free trade, in the belief it would give the U.S. access to Canadian forests and lead to eventual annexation.31

MEANWHILE, AMERICAN explorers continued to dominate the race to the North Pole. With enthusiasm similar to an earlier generation’s conquest of the Wild West, they viewed the Arctic as a new frontier, a place of high adventure, with the added incentive of obtaining honour and prestige for their country. References to Manifest Destiny were also evident in their rhetoric, emphasizing the expectation that eventually the U.S. would possess the whole of North America including the Arctic. Yet in terms of zeal, rhetoric and achievements, none compared to those of Robert E. Peary. A former officer with the U.S. Navy, Peary had taken an extended leave in 1886 to conduct his first Arctic exploration, which was followed by numerous others from 1893 to 1909. Although criticized for his aggressive self-promotion, he nevertheless was responsible for extensive mapping and collection of scientific data for northern Greenland and Ellesmere Island. Peary claimed his quest was not driven by the desire for personal glory, but he believed reaching the Pole was a matter of national honour, “our manifest privilege and duty.” The U.S. War Department agreed, as did President Roosevelt, who maintained ongoing correspondence providing encouragement and commendation. Canadian historian Clive Holland, however, suggests that one of Peary’s letters to his mother revealed another side of the ambitious explorer, when he wrote, “I must have fame, and I cannot reconcile myself to years of commonplace drudgery.” 32

In the summer of 1908, Robert Peary sailed from Sydney, Nova Scotia, on SS Roosevelt, built to his specifications with American timber in an American shipyard. His sole destination was the North Pole, which he hoped to claim for the U.S. as its “natural northern boundary.” His repeated emphasis on the importance of claiming American sovereignty over as much of the Arctic as possible suggested that Canadian concerns of possible encirclement were not entirely unwarranted. Finally on 6 April 1909, with great excitement, Peary wrote in his diary that he had finally reached the North Pole, where he unfurled the Stars and Stripes and claimed possession in the name of the United States of America.33 Although Dr. Frederick Cook declared that he had reached the Pole first, Peary was initially accepted as the rightful holder of the honour, with President Taft quick to acknowledge that his success had “added to the distinction of our Navy, to which he belongs, and reflects credit to our country.” 34 As uncertainty grew to whether either Cook or Peary had reached the Pole, Canadian officials were quite content to let the controversy rage without having to acknowledge the success of either party.

After 1909, Peary no longer actively participated in polar exploration but he was behind the scenes advising American explorers and pressing them to continue their search for uncharted islands. Dr. Donald MacMillan, a member of Peary’s North Pole expedition, took up the challenge and led an expedition in search of “Crocker Land,” a land mass that Peary claimed to have sighted north of Axel Heiberg. Pre-departure publicity emphasized that he hoped to find undiscovered lands to claim for the U.S. Allegedly with a presidential endorsement, MacMillan set out for Ellesmere Island in 1913 on an expedition lasting fifty-one months and covering 9,000 miles. Although he failed to find any sizable uncharted islands, Canadian sources believed that he might have discovered three small islands as well as veins of coal on Ellesmere Island and Axel Heiberg.35

Robert Peary at the North Pole. Although the original caption of this photo taken on 1 April 1909 suggests that Peary was among those waving their hands under the Stars and Stripes, text with a similar photograph by the National Geographic, which co-sponsored the expedition, describes the five figures as Peary’s assistants and notes that the actual location was approximately 30 kilometres from the North Pole.

S0014657, Royal Geographical Society, photographer unknown but likely Peary

Meanwhile whaling activity had come to an abrupt halt in both the eastern and western Arctic, replaced in some locations with trade for furs and ivory. Yet because of Britain’s vague description of the lands transferred to Canada, the task still remained to protect British claims to the Arctic Islands. Prime Minister Robert Borden and his Conservative government were not convinced that Laurier’s concerns about Arctic sovereignty warranted the expenditure incurred by the Bernier expeditions. They were willing, however, to fund Vilhjalmur Stefansson’s Canadian Arctic Expedition in 1913, on the proviso that he make a concerted effort to identify and claim previously undiscovered lands for Canada. Financial support was also rationalized as a means of eliminating foreign sponsors who had offered to fund his original proposed exploration, namely the American Geographical Society and the National Geographic Society.

Canadian officials appeared unfamiliar with the legal protocol attached to laying official claims of possession. Before Stefansson’s departure, the Acting Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs read an article in the Washington Post that accused Britain of actively taking possession of new lands in the Arctic. Realizing that there was no record of correspondence granting authority for Stefansson to claim title for Canada, William J. Walker contacted officials in London for advice. On 10 May 1913, the British colonial secretary stated in a despatch to Canada’s governor-general that under new interpretations of international law Canada could not claim possession of new lands without first obtaining written authority from Britain to do so, implying that Bernier’s claims of possession might be invalid. The despatch went on to formally convey, “under advice of the Privy Council, such authority to the Governor General of Canada to take possession of and annex to his Majesty’s dominions any lands lying north of Canadian territory.” The colonial secretary also advised that “as it is not desirable that any stress should be laid on the fact that a portion of the territory may not already be British, I do not consider it advisable that this despatch should be published, but it should be permanently recorded as giving authority for annexation to the Governor General in Council.” 36 Fortunately for historians, the correspondence was retained as evidence of the British approach in dealing with potential sovereignty problems—asserting publicly that the title was secure, while quietly taking action to correct any weaknesses—an approach later adopted by Canadian officials.

As it happened, Stefansson succeeded where MacMillan had failed, by discovering four previously unclaimed islands of reasonable size. Meighen Island was located northwest of Axel Heiberg, whereas Brock, Borden and Lougheed Islands were discovered west of Ellef Ringnes. With the exception of Brock Island, named after the head of the Geological Survey, the other islands were named after senior government leaders responsible for funding the expedition, a tradition dating back to the age of Martin Frobisher. The expedition might have been considered an unqualified success had it not been plagued by internal dissension and sinking of the expedition ship Karluk. Stefansson was a visionary and believed the Arctic would someday become the “Mediterranean of the North” because of commercial air routes between Europe and Asia. Although his tendency toward personal aggrandizement and continual pressure on the Canadian government to fund further explorations would make him unpopular in Ottawa, his lectures and books on the Arctic found a captive audience south of the border.37

Meanwhile, the demise of the whaling industry had left many Alaskan Eskimos without employment and access to goods such as flour, molasses, tobacco, guns and ammunition. As the demand for white fox increased, fur-trading posts soon replaced the whalers’ supply of goods but often required the Eskimos to travel great distances to the nearest post. The loss of traditional hunting skills due to introduction of the rifle added to their increasing dependence on the white man for their very survival. Disease had already decimated their numbers and many camps were threatened with starvation because too many caribou had been killed to feed and clothe the whaling crews. In an attempt to increase their food supply, in 1890 the U.S. government initiated a reindeer herding project, with mixed results. The once vibrant, self-sufficient Eskimo communities were now often destitute, causing one Soviet scholar to blame “colonial exploitation promoted by American capitalism.” 38 Consequences encountered in Hudson Bay and Cumberland Sound were similar, yet less devastating because of assistance provided by Catholic and Anglican missions. Greenland Inuit, on the other hand, were even less affected as a result of welfare assistance and increased fish trade.

As the Hudson’s Bay Company’s trading posts in the eastern Arctic slowly expanded northward, they were joined by church missions to form the nucleus of tiny settlements, such as Lake Harbour (1911), Cape Dorset (1913) and Repulse Bay in Foxe Basin (1916). Private traders congregated in the Eclipse Sound area of northern Baffin Island, while the French-owned Reveillon Frères Company expanded its trade into northern Quebec and southern Hudson Bay. Aside from the sole police detachment that had moved from Fullerton Harbour to the site of a trading post at Chesterfield Inlet, the fur traders became the figures of authority to the Inuit; missionaries looked after their spiritual needs. The Canadian government was conspicuous by its absence north of Hudson Strait. New HBC posts also opened in the western Arctic from the Mackenzie Delta eastward to Coronation Gulf. Catholic and Anglican missions soon followed. In response to reports of Inuit violence, a police detachment was established at Tree River east of Bathurst Inlet.

In the High Arctic, the islands north of Lancaster Sound remained uninhabited except for occasional groups of Greenland Inughuit arriving at Ellesmere Island to hunt muskox or polar bears. Otherwise, there were no signs of “effective occupation” in the High Arctic by Canada or any other country. Even at more southerly settlements, the Canadian government made no effort to provide the Inuit with better accommodation, education or medical services as the Danes had done in Greenland. Instead, welfare assistance was left to the discretion of fur traders, health and education to the missionaries and housing to the Inuit.

Elsewhere in the circumpolar world, conflicts seemed easily resolved through bilateral or multilateral cooperation. A case in point was the 1911 Convention for the Preservation and Protection of Fur Seals, which had been prompted by concerns for the dwindling population of the sea mammal, coveted for its lush fur. Signed by Great Britain, Russia, the U.S. and Japan, the treaty prohibited pelagic sealing in the Bering, Kamchatka, Okhotsk and Japan Seas. In terms of establishing a precedent, the agreement specifically excluded aboriginal hunters from the ban. According to Donald Rothwell, a law professor at the University of Sydney, the treaty’s success was attributable to the fact that it was “characterized by unique environmental factors, relatively simple government regulations, and an absence of new entrants.” 39

Specific disputes over sovereign rights in the Arctic were more difficult to resolve, particularly if valuable resources were involved as was the case with the remote Svalbard Islands. Because of the abundance of whales and walrus, sovereign authority over the islands and their surrounding waters had been contested at one time or another during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by Britain, Denmark, Norway and the Netherlands. When Russia protested Danish and Norwegian claims in 1871, there was a compromise agreement that the islands would be treated as terra nullius. At the end of the nineteenth century, discovery of coal threatened to reopen the dispute, particularly between Norway and Russia, which were actively mining in the vicinity of Longyearbyen and Barentsburg, respectively. The issue was finally settled by the Svalbard Treaty of 1920 concluded at the Versailles Peace Conference, in which Norway was recognized as “the territorial sovereign of the island” based on initial discovery by the Norse in the twelfth century. Signatories to the treaty, including Sweden, Denmark, Great Britain, the Netherlands and Russia/USSR, were allowed equal access to the territorial waters and ports, along with rights to mine or carry out other commercial and industrial operations. In return, participants in such a venture were expected to pay a royalty to Norway. To maintain its right to sovereign authority, Norway continually updated local regulations such as mining codes and provided infrastructure services.40 The islands themselves are relatively barren, affording sparse food for only a few species of land-based mammals and no indigenous population. Although the islands are a popular site for scientific research, coal mining is still the only industrial activity, with mines still operated by Norway and Russia. The integrity of the treaty will be tested if sizable amounts of more valuable minerals are discovered.

With the exception of the Stefansson and MacMillan expeditions, polar exploration had ceased during the Great War. Yet new technologies developed for military purposes provided even greater incentives to resume efforts at the war’s end. Aviation advances, in particular, created visions of commercial polar air routes to Europe and Asia. Stefansson’s stories of potential exploitation of resources added to the appeal. Although the honour of being first to reach the North Pole and traverse the Northwest Passage was now history, air travel offered easier access and a new form of adventure. Once again, the Arctic gained the attention of the American public. The U.S. government continued to reject the Sector Theory, declaring the High Arctic terra nullius open to exploration by all nations with the assumption that previously undiscovered lands could be claimed by the sponsoring nation.41 Canada was at a clear disadvantage. With the exception of Captain Bernier, there was no avid interest or financial resources to support a private polar expedition. As before, it became the government’s responsibility to ensure that there were no more uncharted islands in the Archipelago.

The same issue concerning terra nullius arose when Knud Rasmussen, a young Dane in charge of Greenland’s most northerly trading post, declared that Ellesmere Island was a no man’s land and that the only authority in the area was exercised through his station in northern Greenland. His written statement was made in response to a Canadian request for assistance from the Danish government to restrain Greenlanders from killing muskox on Ellesmere Island. The Danish note that accompanied Rasmussen’s reply reiterating his position cautiously stated that the government thought “they could subscribe to what Mr. Rasmussen says therein.” 42 In response, the Canadian government issued a formal protest on 13 July 1920 and referred the matter to the Advisory Technical Board (ATB), an ad hoc committee allegedly created to deal with “technical matters” related to northern affairs. The committee was composed of senior officials of agencies reporting to the Department of the Interior, some of whom had been involved in the Alaska boundary dispute.

While the issues were essentially the same as described in 1904 by King, the committee again reviewed the validity of British title to the Arctic Islands. As an additional reference, Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs Sir Joseph Pope provided the board with a copy of Oppenheim’s Treatise on International Law. Although the treatise was published after King’s report, the only difference appeared to be the finality of Oppenheim’s assertion that if a period of time “lapses without any attempt by the discovering State to turn its inchoate title into a real title of occupation, such inchoate title perishes and any other State can now acquire the territory by means of an effective occupation.” As before, the committee feared that British discovery claims were insufficient to maintain title to portions of the uninhabited Arctic Islands, particularly Ellesmere and islands to the west, where Norwegian Otto Sverdrup and American Donald MacMillan were reported to have made a number of recent discoveries.43

The situation acquired a sense of greater urgency that September, when Rasmussen announced plans for his Fifth Thule Expedition, which was to follow a route from Greenland across the Canadian Arctic to Alaska. Although the stated objective was to conduct scientific studies, Canadian officials feared there was a hidden agenda based on rumours that the Danish government was funding the project. After an initial report on Rasmussen’s plans was presented to the ATB in September, Stefansson was asked to attend a meeting on 2 October 1920 to give his thoughts on the subject. His report was alarmist and exaggerated, describing Rasmussen’s scientific study as a “commercial venture” designed to acquire the uninhabited Arctic Islands for Denmark. The self-serving aspect was clearly evident when he argued the need for further exploration, which he offered to undertake for the government. At the end of his presentation, members agreed that a special subcommittee should be set up to deal with the sovereignty question, chaired by Surveyor-General Dr. E. Deville and with J.B. Harkin of Dominion Parks as secretary. Other members included Dr. O. Klotz, J.J. McArthur and Noel Ogilvie, who had assisted in legal preparations for the Alaska Boundary Tribunal. Deville set out three points for the committee to study: the necessary steps required to secure Canadian title to the islands; a review of whether the lands were worth protecting; and the advisability of further explorations.44

Following the meeting, Stefansson was asked to meet with Prime Minister Meighen, his legal adviser Loring Christie and another cabinet member. In anticipation of the meeting, he submitted an outline of the steps that should be taken, which included further explorations, creation of a revenue cutter service, additional police posts on Baffin Island, further mapping and economic surveys and a policy to encourage further development involving private enterprise.45 On 28 October 1920, Christie also wrote a lengthy report for the prime minister, outlining the legal arguments that supported Canadian claims. He noted that immediate attention should focus on Ellesmere Island as “action there seems urgent; action elsewhere seems necessary but not urgent.” While he also argued that a further government expedition was required, he suggested that it be regarded as an extension of the Stefansson and Bernier expeditions “since they were designed and announced as an integral part of the policy making good Canadian claims to the northern islands,” and that showing the “continuity of our policy [is] an important point.” 46

Sir Joseph Pope also reported to the prime minister after meeting with Stefansson, advising that he reject the explorer’s suggestion that Canada lay claim to Wrangel Island north of eastern Siberia, but reiterating that the islands north of mainland Canada might be vulnerable unless claims were followed up by some form of effective occupation. He also supported the idea of setting up police posts on Ellesmere and reminded the prime minister that “in the past our territorial claims have suffered not a little by inaction and delay.” 47 The latter comment likely referred to construction the previous summer of a police post at Port Burwell near the entrance of Hudson Strait, some fifteen years since first recommended.

A series of reports by the ATB’s secretary further clarified the issues, defined the region’s importance and proposed a number of actions to accomplish effective occupation. They recommended establishment of police posts in the High Arctic to enable regular land patrols and enforcement of game laws, with an annual government expedition to assist in setting up and supplying the new detachments. Other measures proposed included expansion of HBC posts throughout the Archipelago and possible transfer of Inuit families from overcrowded areas in the south to uninhabited islands in the High Arctic.48

Particularly disturbing that winter were newspaper reports that Donald MacMillan planned to search for uncharted lands west of Ellesmere with the object of claiming them for the U.S., or in another version that he intended to circle Baffin Island to map additional uncharted lands. It was also brought to the committee’s attention that the latest Century Atlas had highlighted the U.S., Alaska and Ellesmere Island in the same colour. Parliament’s initial response to news of the Fifth Thule Expedition reflected a sense of panic and lack of knowledge among some officials when they proposed that Canada should send an advance party to Ellesmere Island by hydroplane or dirigible from Britain, which was rejected outright by the Minister of the Interior.49

Conservative Prime Minister Arthur Meighen’s preference had been for a more prestigious expedition by the famed British explorer Ernest Shackleton, but when Shackleton reported that he was unavailable, approval was finally granted to refit CGS Arctic for use as an annual patrol boat. After nine years as a lightship anchored in the St. Lawrence and largely dismantled, the ship was towed to a government dry dock for assessment. The refit proved to be a major challenge and costly. John Davidson Craig, a Dominion Lands surveyor and a member of the International Boundary Commission, was appointed to take charge of the overall preparations. His innocuous title of “advisory engineer” to the Department of the Interior reflected the secrecy attached to his position, as with the equally ambiguous name of the Advisory Technical Board. In the winter of 1920–21 the police, now renamed the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), began making preparations for the construction and staffing of two new police detachments, one on Ellesmere Island and the other on Baffin Island.50

CGS Arctic in dry dock, c1921, was being refitted for an Arctic expedition after having been stripped and anchored in the St. Lawrence River as a lightship. Although compared to the HBC’s supply ships the government ship seemed outdated and minuscule, CGS Arctic made four more trips to the High Arctic before being scrapped.

LAC, C-143189 from James Bernard Harkin Fonds, MG 30 E 168, vol. 1, file: May–December 1921

Complicating the issues raised by the proposed Fifth Thule Expedition was a report that a white fur trader had been killed by Inuit in the vicinity of Admiralty Inlet on northern Baffin Island. The request from the trader’s family in Newfoundland for a full investigation had been left unanswered, as the site of the incident was beyond the reach of the nearest police post at Chesterfield Inlet. To do nothing, however, would indicate to other countries that the police were incapable of enforcing law and order in the area. The proposed government expedition for the summer of 1921 provided a perfect solution and a contingent of RCMP officers were placed on standby for the journey north. One new detachment would be established on Eclipse Sound, a location that would allow for a proper police investigation.

Problems of enforcing Canadian laws among the Inuit had become a matter of increasing concern for the police amid reports of increasing violence. Apart from maintaining law and order to provide stability in the region, the ability to administer justice was considered critical to establish effective occupation throughout the Arctic. Episodes of Inuit violence within their own communities had been ignored in the past, but recently there had been a number of attacks on white men in the western and central Arctic. Sometimes the alleged murderers could not be found, but in the case of two Catholic priests killed in 1913, the police arrested two Inuit and brought them to trial. Originally they were given the death penalty, but this was commuted to life sentences of hard labour. In the end, the prisoners worked at a police detachment for only two years before being released back to their community, where they described how they had been provided with food, clothing, a warm place to live and material goods. Not surprisingly most Inuit perceived this form of punishment as tantamount to a reward. With Inuit violence again on the increase, the police believed that their prior leniency was responsible and hoped for a clear-cut case to prosecute as a deterrent against further violence.51 The building of a police post in North Baffin provided just such an opportunity to bring the guilty parties to justice and at the same time show the world that Canada could assert its laws in more remote regions of the Arctic.

On 9 June 1921, the immediate crisis of the proposed Fifth Thule Expedition was unexpectedly resolved when a telegram arrived from the British Colonial Office to advise that the Danish government had provided written assurances that Rasmussen’s expedition was strictly a scientific investigation and that “no acquisition of territory whatsoever was contemplated.” 52 With an eye to costs, the Conservative government immediately halted preparations and deferred the expedition for at least a year. RCMP Commissioner Perry was momentarily at a loss about his pending police investigation until he learned that the HBC planned to open a trading post at Pond Inlet that summer. As a consequence, a lone police officer, Staff Sergeant A.H. Joy, was sent on the HBC supply ship to stay at the new Pond Inlet trading post for the sole purpose of investigating the death of the white fur trader. In the event Joy verified that a murder had taken place and that he could locate those responsible, he was ordered to take them prisoner and await further instructions.

Stefansson, meanwhile, had become disenchanted with the Canadian government, only partly for rejecting his offer to conduct further explorations. More irritating to him was the government’s refusal to claim title to Wrangel Island, after the survivors of the wrecked Karluk had allegedly taken possession in 1914. Without the government’s knowledge or approval, Stefansson created a private firm named the Arctic Exploration and Development Company and in 1921 sent a party of Inuit and a few white men to occupy the island. In spite of Stefansson’s argument about the island’s importance for future air routes, first to the Canadian government then to the U.S., neither country was prepared to claim the island. Finally on 19 August 1924, a Soviet warship, Red October, arrived at the island and raised the Soviet flag on a 36-foot pole, with “Proletarians of every country, unite!” inscribed at the base. A formal ceremony of possession took place the next day and a single American and twelve Inuit from Stefansson’s private expedition were unceremoniously removed. Two years later, the Soviets sent a permanent party to occupy the island, consisting of sixty Chukchi with a former Red Army officer and his family, in the second known incident in Russian/Soviet history where Native people were used to protect claims to sovereign authority.53 Having lost his credibility in Ottawa, Stefansson departed for New York City, where he continued his writing and public lectures until eventually he was hired by the U.S. government as an adviser on Arctic issues.

With the return of the Liberal government to power in September 1921, approvals were easier to obtain for the proposed Arctic expedition and construction of new police posts. Thus a year later than planned, CGS Arctic sailed from Quebec City in July 1922 with Captain Bernier again at the helm. This time, however, J.D. Craig was in overall command and accompanied by nine RCMP officers to build and staff the new detachments. On the first trip of what would be called the Eastern Arctic Patrol, the government party included Squadron Leader Robert A. Logan, sent by the Canadian Air Board to locate sites for future airfields, a surveying crew, a medical officer to report on the health of the Inuit and a cinema-photographer to record the activities of the expedition. There was no public send-off or press coverage and any radio communication was to be brief and in code. The government party, police and crew were under strict orders to maintain secrecy until the police stations had been built. For the same reason, all news releases were carefully censored by Ottawa officials.54

Rasmussen’s claim that Ellesmere Island was a “no man’s land” has often been cited as a wake-up call that forced the Canadian government to take responsibility for its Arctic islands. Partly true if applied to the Union and Conservative governments in power during the war and immediate postwar years, but in the mind of Liberal politicians, the new police posts and Eastern Arctic Patrol were merely a continuation of their policy set out in 1902.55 The Liberal government under William Lyon Mackenzie King also enacted changes to management of the northern territories, largely a consequence of the discovery of oil in 1920 at Norman Wells on the Mackenzie River. Fearing a possible influx of prospectors as had occurred during the Klondike gold rush, Ottawa revamped the Northwest Territories Council and gave it increased powers to enact legislation. The Deputy Minister of the Interior was appointed commissioner of the NWT Council and the number of members was increased to include representatives of various departments involved in northern affairs. At the same time, the Northwest Territories and Yukon Branch was established within the Department of the Interior, under the direction of O.S. Finnie, a former Yukon gold commissioner. His mandate was to establish offices in the Mackenzie District and posts in the Arctic Islands, “where there was grave danger of our sovereign rights being questioned by foreign powers.” Administrators, mining engineers, scientists and medical officers were assigned to staff offices throughout the Yukon and the Mackenzie District, whereas Finnie was located in Ottawa to better influence political decisions affecting northern Canada.56

In 1921 another outbreak of Inuit violence occurred in the western Arctic, not far from the site of previous murders but this time involving the deaths of four Inuit, an RCMP officer and an HBC trader. When added to Sergeant Joy’s report that he was holding three prisoners for the alleged murder of a white fur trader near Pond Inlet, the news convinced the RCMP commissioner that previous leniency had resulted in complete disregard for Canadian authority. In consultation with the Department of Justice, two public trials were scheduled for the summer of 1923, one at Herschel Island in the western Arctic, the other at Pond Inlet in the eastern Arctic. The two Inuit on trial at Herschel were found guilty and later hanged. The trial at Pond Inlet, however, had greater significance for Arctic sovereignty because of its proximity to Greenland. Furthermore, a member of the Fifth Thule Expedition had reported to the RCMP detachment at Chesterfield Inlet that near Igloolik he had met one of the alleged murderers, who talked openly about killing the trader and seemed proud of his actions. Hence the trial at Pond Inlet would serve a dual purpose, namely to deter further violence by the Inuit and secondly to show Danish officials in Greenland that Canada was capable of enforcing laws and administering justice in the Arctic Islands.

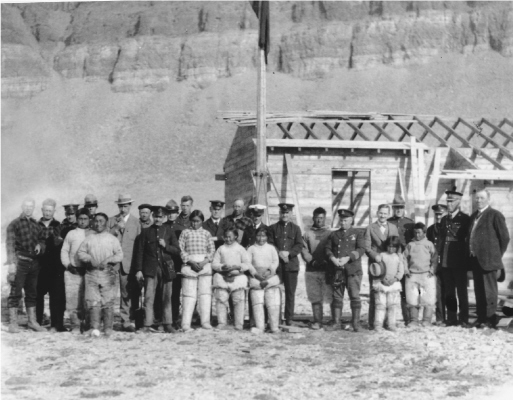

With the court party wearing flowing black robes and accompanied by eight policemen in their scarlet dress uniforms, the spectacle could not fail to impress those present, including Therkel Mathiassen of the Fifth Thule Expedition, who had arrived unexpectedly. Of the three Inuit on trial, Nuqallaq, who had shot the fur trader on the advice of others, was sentenced to ten years at Stony Mountain Penitentiary in Manitoba. Aatitaaq was acquitted for lack of evidence and Ululijarnaat was sentenced to two years’ hard labour at the Pond Inlet detachment, again a punishment perceived by the Inuit more as a reward. As further assurance that the world should know Canadian justice was properly dispensed, a film of the trial was distributed by Fox Films movie theatres in the U.S., with an additional showing of the movie during the patrol’s annual visit to Greenland the following summer. In spite of good intentions, Nuqallaq was released from the penitentiary in less than two years because he had contracted tuberculosis. In the expectation that the cold air would arrest the disease, he was returned to Pond Inlet, where he died within a few months. As one might have expected, an outbreak of the disease was reported the following year. Yet the trial was considered a success since reported incidents of Inuit violence throughout the eastern and central Arctic had decreased dramatically since the event.57

The first murder trial in the eastern Arctic was held in August 1923 at the Pond Inlet RCMP detachment on northern Baffin Island. During a recess, members of the court party are seen here in in black gowns in deep discussion with several police officers, the translator and officers of the CGS Arctic. LAC, PA-187325, Tredgold Collection

(inset) George Valiquette, seen here at Pangnirtung in September 1923, was the cinema-photographer hired by the Canadian government to take movie films of the 1923 Eastern Arctic Patrol and the murder trial for distribution in the United States and Greenland, as evidence that Canada was “effectively occupying” the Arctic Islands.

LAC, PA-207813, Louise Wood Collection

Between 1922 and 1926, five new police detachments were built in the eastern Arctic—at Craig Harbour on Ellesmere Island, Pond Inlet on Eclipse Sound, Dundas Harbour on Devon Island, Pangnirtung on Cumberland Sound and Lake Harbour on the southern coast of Baffin Island. The number of HBC trading posts also increased, as did Anglican and Catholic missions. As a result, the region was slowly acquiring permanent settlements, with sufficient patrols and administrative actions performed by the police to ensure that Canadian sovereignty was well protected by clear evidence of effective occupation.

The incentive to develop a more comprehensive plan would require a more significant threat, as occurred in 1925 in the form of a direct challenge from the U.S. Navy. Under the guidance of Dr. O.D. Skelton as the newly appointed under-secretary of state for external affairs, Canada’s response adopted a more professional approach based on a clearly defined strategy. Formerly the dean of arts at Queen’s University, Skelton had been recruited by Prime Minister King, first as an adviser, then to replace Sir Joseph Pope as head of External Affairs. Skelton was a staunch nationalist and skilled negotiator. More importantly, he had the ear and respect of the prime minister to facilitate approval for immediate action. He also shared King’s belief that Canada should become more directly involved in international affairs and less dependent on Great Britain.58

The foreign policies of Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, William H. Taft and Woodrow Wilson had all envisioned the U.S. Navy “as an active instrument of national policy which might be used for possible coercion of foreign powers.” 59 Hence any direct involvement in Arctic exploration by the navy would be considered a serious threat to Canadian sovereignty. Wartime advances in aviation and shortwave radio communications had added to the potential threat, as the U.S. War Department was now convinced that air power would play a major role in defending the Arctic, perceived as necessary for the security of North America. Following the war, the navy retained responsibility for military aviation and, as a result, was under intense pressure to find uncharted lands near the North Pole as an advance defence post. Even though it had announced publicly that it was looking for islands “north of Alaska,” its plans involved access through Ellesmere Island. Nancy Fogelson, a history professor at the University of Alaska, argues that the U.S. naval expeditions were publicized as a quest to seek new lands to gain public support, when in fact the Americans knew there was little hope of finding new territory.60 If this were the case, then their objective must have been to acquire lands claimed by Canada in an area the U.S. classified as terra nullius.

In 1921 and again in 1923, veteran explorer Donald MacMillan resumed his explorations. One that attracted the attention of the U.S. Navy was his proposed expedition to Ellesmere Island, sponsored by the National Geographic Society and the Carnegie Institute. Secretary of the Navy Curtis Wilbur approached MacMillan to suggest that his plans might be coordinated with those of the navy to include aerial reconnaissance under the direction of Lieutenant Commander Richard E. Byrd Jr. MacMillan was commissioned and placed in charge of the expedition, with Byrd second in command and responsible for the navy’s pilots, mechanics and aircraft—three Loening single-engine, amphibian biplanes. The expedition included two ships: MacMillan’s schooner Bowdoin, and SS Peary, chartered by the navy to transport the planes. Application of new technologies was also evident in use of sophisticated shortwave radio communications and a K6 Fairchild camera for aerial photography.

Prime Minister W.L. Mackenzie King on the porch steps of his home at Kingsmere, Quebec, with his sister Jenna (Mrs. H.M. Lay) and Dr. O.D. Skelton, 29 July 1923. King’s close relationship with Skelton enabled the latter to act quickly and decisively on Arctic sovereignty matters after being appointed under-secretary of external affairs in 1925.

LAC, C-026031

After first learning of the MacMillan-Byrd expedition from an American newspaper, later confirmed from informal discussion with Commander Byrd himself, Canadian officials feared that the U.S. Navy might attempt to lay claim to Axel Heiberg and portions of Ellesmere Island, where Canadian title was weakest. Certainly Donald MacMillan anticipated such an event when he wrote to the Secretary of the Navy to affirm that all lands discovered by U.S. planes “will be claimed in spite of Canada’s protest.” 61 To deal with this and other Arctic sovereignty issues, the Canadian government created an interdepartmental committee, soon renamed the Northern Advisory Board by an order-in-council on 23 April 1925, essentially replacing the special subcommittee of the Advisory Technical Board. Meetings were chaired by either Deputy Minister of the Interior W.W. Cory or Under-Secretary of External Affairs O.D. Skelton, and attended by the deputy ministers of national defence, justice, customs and revenue, the RCMP commissioner and other high-ranking officials representing key interests in the north.

At the first meeting, the only item on the agenda was the proposed MacMillan expedition, with adviser James White warning that if Mac-Millan should succeed in finding new islands, “Canada would have trouble establishing title thereto.” Under existing regulations, it was determined that MacMillan would require a permit from the Royal Canadian Air Force to land planes on Canadian territory, as well as permission from the Customs Department. It was also agreed that Cory, who happened to be in New York at the time, should try to meet with MacMillan and inform him of the permits required to land in Canadian territory.62 In a separate memo to Cory, Skelton outlined the main questions raised at the meeting:

First, the validity of Canada’s claim to the Arctic Islands and of possible counter claims, and second, what steps could be taken to strengthen and assert Canadian sovereignty, whether by making the whole Archipelago a game sanctuary, or by amending the North West Territories Act to require a permit from all expeditions entering our territory, or further acts of administration by Interior, Customs, Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Indian Affairs officials.63

Unable to locate MacMillan, Cory instead had what appeared to be a very productive meeting with Commander Byrd, who assured him that “no expedition will go forward without the approval of the Canadian Government.” On his return to Ottawa, however, Cory received a very polite but apologetic letter from Byrd, explaining that he had orders from Admiral J.P. Moffett that he was not to get involved with “that end of the Expedition.” The Northern Advisory Board immediately set up a subcommittee to begin drafting a despatch to the British ambassador in Washington that included a request for further information about the purpose of the MacMillan/Byrd expedition. The inquiry included the assumption that “the United States recognizes Canada’s claim to the territory indicated on our map of the North and that those in charge of the expedition will comply with Canadian Laws and Regulations.” 64

The subcommittee, meanwhile, had prepared a “Statement of Canada’s Claims to the Arctic Islands” that set out the precise boundaries and a lengthy legal argument in their support. Included was a detailed description of police activities, other evidence of effective occupation and the permits required for visiting explorers. Significantly, the boundaries of Canada’s northern hinterland were defined in accordance with the Sector Principle as “the area bounded on the east by a line passing midway between Greenland and Baffin, Devon and Ellesmere islands and thence northward to the Pole. On the west, Canada claims as the boundary the 141st meridian from the mainland of North America indefinitely northward without limitation.” 65

As required by protocol, the request for information required approval by the British ambassador in Washington before being forwarded to the U.S. State Department. A note to the ambassador suggested that, if deemed necessary, the “Statement of Canada’s Claims” might accompany the request for information. Also included in the letter was an offer from the RCMP to provide assistance to the expedition while it was in Canadian territory. Skelton had taken a calculated risk in declaring boundaries that might be declared invalid if challenged in an international court of law. In a sense it was a bluff, as there was no evidence that the Canadian government had previously asserted any administrative acts in the northwestern portion of Ellesmere Island, nor that any Canadian had ever set foot on the Sverdrup Islands. The ball was now in the State Department’s court. Would it protest Canada’s claims? If so, on what grounds?

Forwarding correspondence from Canada’s External Affairs to the U.S. State Department through the British ambassador was a tedious process that usually involved delays and requests for revisions. On 4 June, the letter along with the “Statement of Canada’s Claims” was sent under the signature of Governor-General Lord Byng of Vimy to the British ambassador in Washington, Sir Esme Howard. To elicit immediate action, Skelton sent a coded telegram to the British chargé d’affaires in Washington on 12 June warning that Minister of the Interior Charles Stewart was preparing for a press interview in which he planned to outline Canada’s Arctic boundaries and the legal basis for the claims.66 The strategy worked. On 15 June, the British ambassador forwarded the despatch on to the State Department, along with the statement of claims.

Secretary of State Frank Kellogg replied a week later, confirming that the MacMillan/Byrd expedition would be flying over and establishing a base on Ellesmere, but he requested more information: “What was an R.C.M.P. post? Where are they established? How frequently are they visited? Are they permanently occupied and, if so, by whom?” On 27 June, the Canadian government replied with detailed information about the location of the police detachments and the extensive functions performed by the RCMP throughout the Arctic Islands. Kellogg formally acknowledged receipt of the note and the earlier one of 15 June, saying a reply would be forthcoming after various departments involved had had a chance to study the notes. This time, there was no further response.67 Canada had followed the proper diplomatic procedures and clearly stated its case. The ultimate test would be whether Canada could enforce the new regulations should the U.S. State Department reject the claims as invalid.

When MacMillan received notice that he would be required to include the registration numbers of the planes and the names of the pilots when applying for a permit to fly over Ellesmere Island, he sought the advice of the Secretary of the Navy, who in turn advised the State Department. Canada’s request complicated matters, as the U.S. government had always maintained it had not funded any of MacMillan’s exploration activities. In this case, the registration numbers would prove the planes were navy property and the pilots actively employed in the service. Kellogg reportedly questioned the validity of the Canadian position and suggested that because of the nation’s ties with Great Britain the Monroe Doctrine might be invoked “to curb Canadian expansion.” After reconsideration, he admitted that application of the Monroe Doctrine would cause “strained relations for years to come.” In the end, the State Department simply declined to respond.68

Meanwhile, Commander George Mackenzie of the Eastern Arctic Patrol was apprised of the American expedition and asked to look out for the two ships. With approval from the Danish government, SS Peary and Bowdoin had been anchored in Etah Harbour in northwest Greenland since the beginning of August. On the third, MacMillan received a radio message from the navy, warning that CGS Arctic was in the vicinity with an American reporter aboard and that under no circumstances should he be allowed to use the expedition’s radio phone or interview either Byrd or MacMillan. The reporter, actually a Canadian on contract with Fox News, did not get an interview but he did manage to take some compelling photographs, as did others on board CGS Arctic. Further instructions arrived the next day, this time from the U.S. State Department, ordering MacMillan to obtain the necessary permits and avoid “an embarrassing situation by handling the matter informally and diplomatically as possible.” 69 Either Mac-Millan did not receive the message or he ignored it. As a result, the matter was handled neither diplomatically nor informally.

By the time CGS Arctic arrived at Etah on 19 August, Byrd had already flown 6,000 miles on reconnaissance east across Greenland and west over Ellesmere as far as Axel Heiberg. He also landed supplies at Flagler and Sawyer Bays on Ellesmere’s east coast. To his profound disappointment, bad weather forced cancellation of plans to set up further depots on the west coast of Ellesmere and the northern tip of Axel Heiberg. Commander Mackenzie sent his secretary to SS Peary with a message for Commander Byrd, tactfully offering to issue the necessary permits authorizing the expedition “to fly over Ellesmere Island and other Canadian territory and establish on such Canadian territory the necessary bases incidental to such flying operations.” Reportedly dressed in naval uniform, Commander Byrd arrived on board CGS Arctic to report that he had been informed by MacMillan that the expedition had already obtained permission from the Canadian government “to carry on flying operations over Ellesmere.” Since Mackenzie was denied access to the navy’s radio to confirm this information and had no long-range radio of his own, he was unable to verify whether permits had been issued after he had left Quebec City. The Canadian officials departed unconvinced, but unable to take further action. The patrol ship headed directly to the site chosen for an RCMP depot at Kane Basin, where Mackenzie reported that two of Byrd’s planes had circled overhead as they were unloading supplies.70 A small shed was built for emergency supplies until such time as a full detachment could be built and staffed.

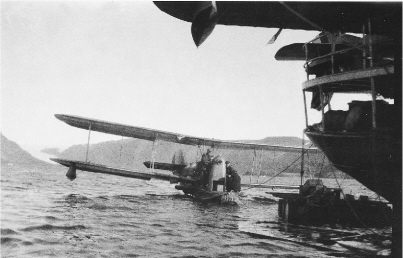

Amphibian plane piloted by Commander Richard Byrd, USN, approaching the stern of the SS Peary chartered by the United States Navy. When CGSArctic met the MacMillan/Byrd Expedition in Etah Harbour, Greenland, 28 August 1925, Byrd had already flown reconnaissance flights over Ellesmere Island and left a cache of supplies on the west coast.