PART I

CLERMONT

By Wisdom a House Is Built

By wisdom a house is built, and by understanding it is established; by knowledge the rooms are filled with all precious and pleasant riches.

–Proverbs 24:3–4, English Standard Version

Behind every great historic structure are the people who built it. More than likely, the land that encompasses White Hall State Historic Site today would be a subdivision of cookie-cutter houses, with no trace of history, if it hadn’t been for one man: General Green Clay. He was the great-great-grandson of Captain John Clay, who sailed in February 1613 from Wales across the great pond to Virginia on the ship Treasurer.1 Known as the “English Grenadier,” originally John and fifty of his men came to America to “protect” the Virginia settlers. Captain Clay had a change of heart, however, and turned over a new leaf (or turned coat, depending on what side you’re looking at); he resigned his post, obtained some land and settled down to family life.2 About 145 years later, Green Clay was born in Powhattan County, Virginia, on August 14, 1757.3 Green was one of eleven children, blessed with his unusual first name by his mother, Martha Green.4

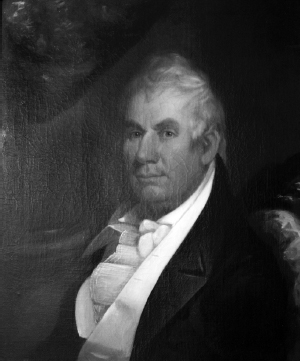

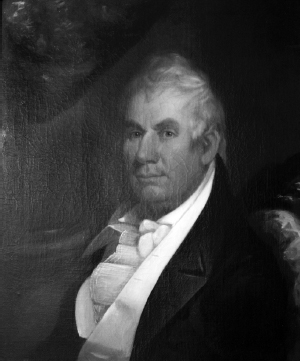

Based on a painting of him, it appears that Green had blue or light gray eyes, with dark hair that went gray as he got older. Green stood at five feet, eleven inches and, according to one account, “was more robust than elegant in person.”5

According to family lore, Green Clay had a little bit of a tiff with dear old dad, Charles Clay,6 and although still considered a minor, he decided to “go west, young man”—in this case, to Madison County, Kentucky. It’s possible that tales of Daniel Boone roused in Green a thirst for adventure that led him to the Bluegrass State.7

Portrait of General Green Clay, believed to have been painted by artist Matthew Harris Jouett. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

Although credited with only having a total of nine months of schooling in regards to math, Green Clay’s “grasp of a subject was quick and comprehensive,”8 and he apparently had enough smarts to learn land surveying. One contemporary account noted that he would ride around on a mule dressed in buckskin pants and a hunting shirt.9 Perhaps his attire threw people off, or it might have been that Clay was a natural-born actor. Legend has it that while traveling the great Kentucky frontier, Green ran across fellow surveyors. When they asked if he understood mathematics, Clay replied, “I knew one George Mattox.” Who knows if Clay was joking or trying to pull one over on the men. In any event, his fellow surveyors took the answer to mean that Green wasn’t the brightest bulb in the pack, so they employed him as their cook and cabin keeper. The joke was on them. After his companions completed their survey, Green copied their paperwork and high-tailed it back to register the property three days before they even got started, entering the land as his own.10 As it has been said, “There’s a sucker born every minute.”11

All of Green’s hard work and shady double-dealings paid off; by 1792, he had been chosen as an official deputy surveyor.12 At times, Green was able to claim up to half of the land he surveyed as payment for his services. Mr. Clay liked his land, and he was never one to pass up an opportunity to add more acreage to his ever-growing collection. Clay was so proficient at this vocation that by the time of his death, he was arguably the largest landowner in the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

With all that land, Clay was able to raise tobacco and sell his crops in warehouses he owned.13 Tobacco may have been a good cash crop at the time, but Green determined at an early point that the plant took too many nutrients from the soil and eventually ceased producing it on his estates.14 Clay also grew rye and wheat in his numerous fields,15 for which his gristmills sold the flour. Clay was the owner of several taverns and provided the spirits for those establishments from his own distilleries, produced by corn that he grew on his properties.16 Green was even the proud owner of a resort—how’s that for entrepreneurship?17

By the mid-1790s, Green Clay had become a magistrate of the court.18 This post was extremely beneficial to him in that he was able to rake in more land and money by being in such an esteemed position. Clay oversaw the settling of estates (old man Wilson had just died, and he doesn’t need that land anymore, so I’ll just take a chunk). He had the authority to sanction the localities and the rights for area roads (we need a toll road in this area, so I’ll just have it go directly through my land) and businesses such as gristmills and warehouses (this is a great area for this type of business, so I’ll put one of mine here). He could appoint individuals as inspectors (I’ll select my good friend Thomas Watts as tobacco inspector, and he’ll look the other way when I need him to),19 and he was able to set the going rate for area taverns, local ferries and neighborhood turnpikes, some of which were owned by him personally.20

Making money took a lot of time, but so did keeping it. It seems that a great portion of that time was spent in court. Clay was known for going to court over nearly anything, and the majority of the time he won. Now and then, his motives tended to be a little on the questionable side. He once went to court to resolve a debt owed to him by a gentleman by the name of William Ranold, who had the misfortune to die before settling with Clay. Although the amount owed to Green was a small one, Green felt that Ranold’s acres would correct the problem, so he sued Ranold’s heirs, described in the court records as “two infant females.” Not surprisingly, Green won the case.21 When it came to his property, Green didn’t even mind taking little girls to court to get what he thought was his due.

Green also spent some time in court for his dubious practice of carving his initials or his name on landmarks, such as rocks and trees, to give other surveyors the impression that he owned them. In reality, Green didn’t own this land, but won the case and was granted the right to go back and actually survey this land and gain possession of it.22 Green’s antics in court were so well known that one land grant issuer informed his subordinate to go ahead and approve Green’s land grants no matter how illegal they appeared because Green would just end up filing a grievance in the court of appeals and acquiring the land anyway.23

Clay’s duplicity caused a bit of a commotion in 1817. Green had acquired court consent to have a ferry travel from his own land across the Kentucky River to land owned by a man named William Bush. Green Clay had acted as an attorney for the heirs of Bush, who in turn granted him the permission. It turned out that the heirs Clay represented weren’t the real heirs, and the lawful beneficiaries took him to court for “fraudulent design” by trying to “gain possession” of their land. While the plaintiff’s attorney was out of town, Clay and his court buddies ruled against the Bush heirs. Although this court case was controversial, in the end Clay got what he wanted.24 It’s good to be the king.

Another time that Green got into a little bit of trouble was for distributing free turkeys to the local people. On any normal day, one would think that Green was just a generous guy, looking out for the well-being and stomachs of his fellow man, much like Dickens’s Scrooge and his Christmas goose. However, the doling out of the tasty birds occurred on election day. Although compatriots might think more kindly of Green when they went to the polls with a full belly, his political adversaries cried foul on the fowl.25

In addition to crops produced on his extensive lands, Green also raised and sold numerous varieties of domestic animals, possibly including the aforementioned turkeys. It was sheep, however, in which he had the most vested interest—particularly Merino sheep, which he had imported into Kentucky and continued to raise until his death.26 Clay oversaw the benefits of this enterprise, from the importation to the wool production (he had a loom house on his own estate),27 as well as the knowledge of how to properly butcher the animals. Apparently, he placed great stock (pun intended) in mutton soup for its nutritional value and its abilities to cure the sick. To describe just how great Green Clay’s interest was in this venture, his youngest son, Cassius M. Clay, stated in his Memoirs with regards to his father, “He was a great lover of sheep.”28 Whether this love was his appreciation for what this type of livestock could provide nutritionally and financially, or for other reasons that the authors won’t go into, we’ll let the reader decide.

When discussing Green Clay’s wealth, it would be impossible to not mention the enslaved individuals whom Green owned. As distasteful as it may seem to modern readers, Green Clay had a vast enterprise in regard to the slave trade. In order to generate all the wealth that his lands were producing, workers were needed, and slaves were the most profitable workers to be had. Green was all about profit.

In his Memoirs, Cassius M. Clay briefly mentioned how his father dealt with his slaves:

Now slavery was a terrible thing; but he made it as bearable as was consistent with the facts. When any of the slaves were found to “play the old soldier,” and pretended to be sick, he had a fine medicine in the bark of the white-walnut. This he would have mixed with much water. If the patient was really sick, it was a safe and excellent remedy for many diseases; but, if he was playing “possum,” he would go to work rather than swallow the bark. There was no market for sheep in those days; and my father’s object of raising large flocks was to clothe his slaves well. He always had the heaviest cloth made for men and women, and then “fulled.” By this operation the web was thickened, and made, like the felting of wool-hats, water-proof. He used to say: “Better lose the value of a coat than that of the workman.” He fed and sheltered his slaves well, allowing them gardens, fowls, and bees. Groups of cabins were far apart for pure air. No man understood better how to manage his dependents. He provided first-class clothing, food, and shelter for his slaves; but always was rigid and exacting in discipline. Of all the men I ever knew, he most kept in view the means which influenced the end.29

Green Clay’s will had 105 slaves listed, all by name, making him possibly the largest slaveholder in the state of Kentucky at the time of his death. Of them, 84 slaves were given, either in trust or outright to his children; 1 slave was given to his wife, with stipulations attached; 12 slaves were emancipated; and 8 were sold.30

With all of Green Clay’s diligence in building an empire, it is astonishing that he found the time to get married and have children, but he somehow managed it. Clay chose for his bride Sally Lewis, the daughter of Thomas Lewis and Elizabeth Payne, a very prominent family who hailed from Lexington, Kentucky, by way of Virginia. Sally’s father played a major role in politics, being a magistrate like Green, as well as a member of the First Kentucky Constitutional Convention. Another claim to fame for Thomas Lewis was that he administered the oath of office to the first governor of Kentucky, Isaac Shelby.31 Green Clay married into this influential family on March 14, 1795. Ms. Sally was nineteen years his junior, having been born on December 14, 1776.32

Portrait of Sally Lewis Clay, artist unknown. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

Green was as successful building his family as he was his empire. Green and Sally had seven children together from 1798 to 1813: Elizabeth Lewis Clay Smith (March 29, 1798–October 14, 1887), Sidney Payne Clay (July 16, 1800–July 2, 1834), Paulina Green Clay Rodes (September 7, 1802–December 15, 1886), Sally Ann Clay Irvine Johnson (September 24, 1804–October 23, 1829), Brutus Junius Clay (July 3, 1808–October 11, 1878), Cassius Marcellus Clay (October 19, 1810–July 22, 1903) and Sophia Clay (March 3, 1813–July 8, 1814)—three boys and four girls, with the youngest child, Sophia, the only child not to survive into adulthood.

Of course, Green was far too busy to have much to do with his children other than to father them. Green Clay’s youngest son, Cassius, mentioned that Green was “a stern man, absorbed in his affairs. He spent but little time with the children, and did not assume control. Yet he directed, in the main, what was to be done.”33 Cassius went on to state, “I saw but little of my father; he was always absent, and when at home was engaged in business.”34 Green may have been stern, but he did have his soft side. Cassius also mentioned that Green “would never allow children to be awakened; but left them, under all circumstances, to sleep on till they awoke of themselves.”35

Based on Clay’s Memoirs, it would appear that their mother, Sally Lewis Clay, as well as the Clay family slaves, primarily raised the Clay children. Although frequently away on business, Green had his influence on his progeny, making sure that they (or at least the boys) were educated and directing them in certain moral areas, as he would not allow his children to play cards or drink alcohol.36 This last moral value made an impression on young Cassius, as he recalled watching his father every morning go to his liquor chest and take out a bottle of bourbon. From this bottle, Green would take one medicinal swig per day before breakfast. All the while engaged in this necessary evil, Green would look at his male offspring with a remorseful face, as if the dose was almost too much for him to bear. Cassius, being a curious sort of child, wondered: if it was good for his papa, why wasn’t it good for the children? Taking a drink on the sly, Cassius found that the “medicine wasn’t really all that bad tasting.” Lucky for Cassius, alcoholism was not a weakness as “the Bourbon itself was not fascinating.”37

Not a great deal is known about Mrs. Sally Lewis Clay. What little information there is established has been gleaned from letters of the time written to or from Sally, a handful of court documents and what her youngest son wrote about her in his Memoirs: “My mother was Calvinist in faith, and, though not believing in good works as the ground of salvation, yet was the most Christian-like and pious of women in every word and thought. With her truth was the basis for all moral character. She would not tolerate even conventional lies, never saying, ‘Not at home’ to callers; but, to the servants, ‘Beg them to excuse me.’”38 This characteristic of his mother would influence Cassius all his life, even in regards to his pro-emancipation views on slavery: “This it was, when I was asked, in order to corner me, if slavery was not a good and Christian institution?—considering all the consequences, remembering her who had given me life and principles to live or die by—that led me to answer No!”39

In disciplining her children, Cassius stated that his mother was “not a woman to be trifled with.” She was very decisive and swift. Mrs. Clay was a firm believer in corporal punishment. Although known for his fighting skills when he got older, the young Cassius was no match for his mamma. Cassius M. Clay stated that his mother whipped him twice in his lifetime, once for fighting with the overseer’s son and the second for lying. On his second offense, Cassius was ordered to come to his mother for punishment. Having been punished with a “rod” from a peach tree, which Sally had not “spared,” Cassius knew what was coming and instead ran away from his mother. The house and kitchen slaves chased after him. Cassius situated himself on a pile of rock and fired stone missiles at anyone who came near him. As he put it, “For, as I had been whipped for fighting, now I fought not to be whipped.”40 Finally, his mother had to take matters into her own hands and came to get young Cassius herself. Cassius then resigned himself to his punishment, stating that “when I found escape neither in running nor in fighting, I ever after submitted with sublime philosophy to the inevitable.”41

Thus far we have established that Green Clay had a very strong head for business and was a mostly absent but loving father. What other traits did he possess? Although one can make speculations on Green’s character based on court records of the time, one of the few documents in existence today that gives any kind of window into Green’s personality was written by Cassius in his own Memoirs. There is little doubt that Green was a courageous man. When called upon, he served his country in times of war. Green Clay was active in the Revolutionary War42 (a portion of his land could have been payment for his service in this conflict), and nearly four decades later, he took up arms once again as a general in order to lead troops to Fort Meigs in the War of 1812. Green was considered a hero in this particular war by coming to the aid of William H. Harrison, who was under siege at Fort Meigs in Ohio. In speaking of his valor, perhaps it was best said by Cassius: “The man who slept often alone in the wilds of Kentucky, among bears and Indians, could not be otherwise than brave.”43

Green played a prominent role in politics, as he was a member of the House of Burgesses in Virginia, and he attended the convention that ratified the Constitution of the United States. He also served in the Kentucky legislature and the state Senate,44 but rising to political distinction was not something that he desired. Cassius revealed, “Those who knew him best compared him favorably with Henry Clay; and, had all his powers been concentrated in one direction, they thought he would have reached equal eminence. And these were the opinions of those who were themselves eminent, and therefore very competent judges.”45

Green was a powerhouse of wealth, and he understood the economics of saving, yet he would give generously if the mood struck him. As will soon be discussed in relation to his housing, Green had an appreciation for beauty. He enjoyed music and dancing but considered hunting and gunning a waste of his time.46 Green was known to have a bounteous table, and yet he himself did not give in to common vices such as smoking, drinking or excessive overeating. A common misconception among modern folk is that people did not bathe regularly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Cassius stated that Green was always impeccably dressed and “scrupulously” clean.47 In terms of his faith, Cassius mentioned that his father was a deist.48

Very few personal letters are known to still exist today from those Green Clay penned. One letter (the original is archived in the Green Clay Papers at the Filson Historical Society in Louisville, Kentucky) gives a small glimpse into Green’s life. The following is included with punctuation and spelling original to Green. The letter is dated January 8, 1820, and is addressed to Green’s wife, Sally:

My Dear Salley,

I am now at Mr. Jarretts on the banks of the Tennessee River where I arrived the 17th. Ulto. I sent Jeff last Saturday to Smithland for letters if any were in the post office for me, & gave him two dollars to buy linnen for a bag to carry corn meal in to the woods, and pay the postage on my letters: he came home drunk at night: with four bottles of whiskey along altho I had sent for none, my money all gone, & a bill from the merchant with an account against me for a balance due for bottles & whiskey. I was so provoked I did not know what to do. He had a great big Irishman mounted up on Fox behind him, for he had broake down his horse, so that he will not be fit to ride this winter. Fox was sweating & smoaking cold as the weather was: he had waisted all the day drinking in town got loss and road hard with his man behind him, to keep from lying in the woods all night. I started Sunday for the woods with two bushels of sifted meal & a midling of pork, the 3rd time to go round the 17,000 acres on Clark’s River: The surveyor failed to meet me: Monday Jeff hobbled our horses in the cane on Monday night and I have not seen nor heard of them since: I sent Jeff Tuesday after them, he returned back drunk, went to the first house where there was whiskey & no further: I started him Wednesday another course he went out of sight & then turned round through the woods to the same house (five miles off) where he got drunk the day before, & stayed out all night. I went myself the same day where I thought it was likely I might hear of the horses: but got no tidings of them: Thursday & Friday I traced up about 5 miles & a half of my lines found one corner: it began to rain; & I came back here: the nearest house to my work, I lodged at when I did not lie in the woods all night: and strange to tell the man with a wife & 5 or 6 children had not one ounce of meet of any kind nor a grain of corn or meal; nor a drop of milk or a cow they had some turkey meet when I first arrived; they lived on my provisions while I stayed there & with comers & goers eat up my provisions: this is the 3rd time I have been but not finished the first survey: and here I am a foot. I have hired a man to go with Jeff tomorrow morning, in search of the horses: Jeff’s horse was hobbled with a rope: but if there should be any whiskey in the way, I am informed there is, they will end their journey there I expect. I must start one or 2 more men out after the horses: to morrow or next day. When I left home I took bearly money enough to bear my expenses, & my expenses here are greatly more then I expected corn is 4/6 per bushel, and in some places one dollar. The man Overby sold my whiskey to, is insolvent I cant git one dollar from him: his note is for $221 the greatest plenty if I could git it, to buy me two ponies to take me home: my great coat lieing in the woods is burned in holes: the brush and greenbriars with which this country abounds has tore my sachels, legings, breeches, & great coat into strings or rather rags: here for the first time for many years past, I have dined & supped on dry bread & swamp water, I am compeled to wash down hand mill [bread] with water, I have fellen off 30 or 40 pounds I expect, with the water and the bowell complaint, my fat belly has gone down I am now as gaunt as Brutus almost.

The Indians are encamped all through this County. I am at their camp almost every day but they are like the bees that assembled at Nashvill some years ago. Quite harmless to all appearance they live wandering about seeking game and realy git more of it, and live better then half the whites: in this quarter. When Jeff has whiskey he is all noise and bustle when none he mopes about and dose but little: he is the merest Spencer that I ever saw. I had better been by myself. I am in verry good health most of my time, and all my complaints are the effects of fateague cold and hunger. You must not send me any money in bank bills by the mail for I shall be gone hence before it would arrive here. The hogs in this country are all caught or shot in the woods & killed as they run no such thing as puting up hogs to fatten with corn, the meet eats like boar meet strong & tuff: like all other wild meet nothing like our corn feed pork: bad enough as soon as you receive this letter send to Dan Dan [sic] Stevens & tell him not to make a gallery on the top of the dweling house if he has began it to stop & do no more at it. git all the money you can from Edmond Johnson at Stones Ferry send to him every week or two set all the money in writing you received & the day of the month I hire a man to take this letter to Smithland & bring me letters if any from the office. I wish you could keep the boys at school dont enter them for more than a quarter at a time.

There is a misarable set of people in this country I have wrote everything I have to write from here I am greatly distressed in my mind & I cant Tell when I shall be relieved from it. Give my love to all the children and accept my best wishes for your wellfare and happyness in this & the next world.

Green Clay

Sunday morning Jany 9th

Tuesday morning the man I hired to go with Jeff to hunt my horses has returned & no news of them at all The men are sleeting [possibly means “sledding”] on the Ohio at Smithland last cold weather in gangs—a man was taken sicke at Smithland last Friday & died in 10 hours:

Tell Cassius there is one John Derro making shoes at this house, who says he and another man gathered in the Ohio lowgrounds in six days 65 bushels Of Pecon nuts The weather is as cold again as ever felt nearly Janry 11th 1820. Farewell again:

Green Clay49

After reading this letter, it is difficult not to feel slightly sorry for poor Green. Land surveying was hard work in those days, especially if one had an alcoholic servant with whom to contend. This letter raises many interesting questions. Was Green able to locate his horses? Did he finally finish his survey? Did Jeff get drunk again? Questions also arise as to whether Jeff was an enslaved man or just a servant hired on for the surveying job. Eight years later, when Green passed away, he bequeathed a slave named Jefferson to Cassius to be placed into trust for Green’s daughter, Pauline. Could this have been the same Jeff whom Green speaks so highly of in his letter? It may never be known.

One can also gain some insight into Green’s persona based on sayings he would impart to his son: “Never tell anyone your business,” “Inquire of fools and children if you wish to get at the truth,” “In traveling in dangerous times, never return by the same road,” “Never say of any body what you would not have proclaimed in the court-house yard,” “Well is the tongue called a two-edged sword,” “Keep out of the hands of the doctor and the sheriff” and “My property is worth more on the farm, or in the store-room, than in the pockets of spendthrifts.”50 This last bit of advice Green certainly lived by.

As Green was one of the most powerful men in the county, with numerous enterprises and great wealth, and had his finger (or in this case hands) in all of the political pies, naturally he needed a domicile that reflected his lofty position. When Green purchased the land where the family home still remains, it was a station owned originally by Reverend John Tanner. Because the land was known as a station, it can be inferred that the tract included a log cabin of some kind.51 If there had been a structure already present, Clay could have initially used this residence until building a better log house, or perhaps, considering the tycoon he was to become, he may have wished to save money by living in this original building until his more impressive abode was built. Once the new home was erected, the old four-room52 log structure was left standing at the edge of the yard. It became a residence for the overseer53 and then later was used as an office by Cassius M. Clay until it burned down in 1861.54

It would be a disservice to say that Green Clay “built” his home. So much of history tends to focus on the rich white man and not enough on the reality of the time. Therefore, it should be noted that although Green Clay had the funds and power to produce his domicile, more than likely he never laid a finger on any actual building materials. That would have been the job of hired individuals and, of course, his slaves. Cassius, in speaking of his father and manual labor, noted, “He never put his hand to any work on his large real-estates, because he might injure his limbs, when a subordinate would do the work as well.55 Heaven forbid that Green hurt himself!

Construction began on the estate in 1798 and wrapped up that following year. To produce the brickwork for the home, the builders did not have to travel far, as a pit was dug on the land to provide the clay for the brickwork.56 In addition, good Kentucky marble and gray limestone were used for the range work. This would have been thrifty on Clay’s part and would have shown off some of the natural beauty that the landscape had to offer.

The bricks for the home were laid in a style called Flemish bond, in which stretchers (the long side of the brick) and headers (the short end of the brick) are alternated, with the headers being centered over the top of each of the stretchers. Originally, the house faced north, toward the Kentucky River. This is based on the fact that the front of the house is generally the most decorated, and glazed-headed Flemish bond (where the header bricks are fired to produce a darker, glassier surface) was used on the front façade, providing a fancier look to the brickwork. One account noted that the home had wooden honey locust shingles.57

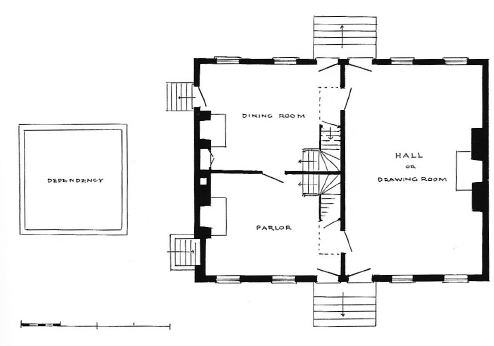

The house was built in the Georgian style, very symmetrical, having both the front and back of the house incorporating double doors, with two windows on each side of the doors and chimneys on each end of the home. Inside there was a bearing wall that would have separated both sets of double doors, dividing the first floor of the house into one large room, used as a main hall, and two smaller rooms, set up as a parlor and a dining room. The rooms on this floor were meant to impress, with twelve-foot ceilings.

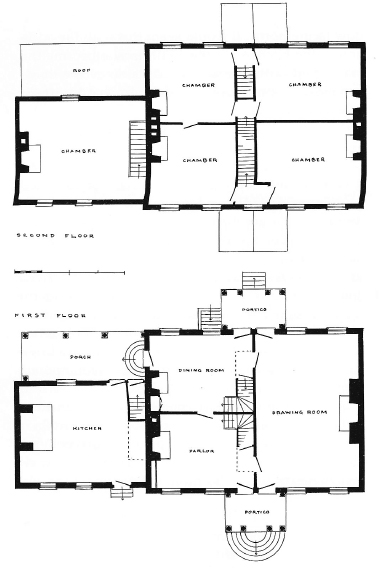

Floor plan of the first floor of the original Clermont. Floor plan and text description taken from Antebellum Architecture of Kentucky by Clay Lancaster, 1991. Courtesy of University of Kentucky Press and the Warwick Foundation.

The parlor and dining room each would have had a staircase leading up to the second floor, where four bedrooms, roughly equal in size, were located. Each bedroom would have had its own fireplace; however, the fireplaces on each end would have shared a central chimney. One more staircase would have traveled up to the garret, which would have run the length of the house.

Underneath the house was a full basement, with dirt flooring divided just like the first floor but reversed. There was a large single room serving as a winter kitchen, located under the parlor and dining room, with access coming from the dining room. This area would have kept food warm before taking it directly upstairs to the diners. On the opposite side under the hall would have been two other rooms. One room may have been living quarters for the cook.

The other room was more than likely a jail cell. As mentioned previously, Green Clay was a magistrate. As there was no permanent housing for those who broke the law in Richmond at the time, Green literally brought his work home with him. It is open for contemplation whether Mrs. Clay liked the idea of having criminals housed below her great hall. Another darker and more probable use for the jail cell could have been for the housing of disobedient slaves. Documentation has never been found on this subject. Some slaveholders of the era would lock up unruly slaves. It is not known if Green did. At the time of the restoration of this building, seven sets of shackles were found within the jail cell. Because the restoration took place in the late 1960s, and the civil rights movement was in full swing, there was a hesitancy to have this area of the home highlighted on tour, and so the shackles were removed.

Oral tradition states that Green Clay bestowed the two-story brick structure with the romantic title of “Clermont.” The origin of the name is not known, although some hypothesize that the name was used as a result of the house being built in a cleared space on a hill.58 It is also open for debate whether the original home actually was named Clermont. Longstanding tradition has always maintained this, and this name has been stated as fact in many publications concerning the original home. However, no primary documentation has ever been found at this juncture to back this up. Indeed, Green never called the home Clermont in any correspondence found, including his last will and testament, simply referring to the home as “dwelling house” and “mansion house.”59 Later, Cassius would refer to his father’s home as “Fort Gen. Green Clay,”60 and other family correspondence would refer to the home place simply as “the farm,”61 so it would be interesting to discover how and when the appellation first took hold.

Watercolor of Clermont by artist Sallie Clay Lanham, great-great-granddaughter of General Green Clay. Courtesy of Sallie Clay Lanham.

The woodwork inside Clermont was fairly impressive, being a mixture of pine, oak, walnut, cherry and yellow poplar. In the late 1960s, when the home was being restored, an attempt was made to refinish the woodwork; however, it was determined to be too difficult, as there were so many types of wood used it would have been impossible to make them look uniform. Therefore all the woodwork was painted over in a cream color. What may not have been known at the time of the restoration was that in Green Clay’s time, as well as that of Cassius, woodwork was not always shown in its natural glory but rather painted a color or faux grained to make the lumber resemble a more expensive type of wood. In the case of Green Clay’s era, paint chips have fallen off to reveal a lovely blue shade—the color the parlor may have been. Later layers of paint reveal a faux graining, which was more than likely incorporated into the parlor in Cassius’s time.

Sometime shortly after 1800 (believed to be about 1810), a two-story structure was built on the west side of the home. This addition was attached to the side of the building, and the only direct access to the main house would have been through the floor of the first level into the basement area. It is believed that the winter or warming kitchen originally located in the basement of the home was moved to the bottom portion of this addition. The cook and his or her family could have moved directly over this room, as there is a fireplace upstairs. This area could also have been a storage area for preserved food, as evidenced by the enormous hooks in the ceiling of the stairwell that it can only be presumed would have held large portions of meat. A porch led off of the north side of this addition and would have also been accessible from a door leading out of the dining room of the house.

Perhaps at this point in time Green Clay decided to change the front entrance orientation of his home, from the side facing the Kentucky River on the north to the south side of the building. Large Corinthian columns would have been added to give this elevation a more impressive façade. It is interesting to note that these original columns were unearthed at a later time on the property. The reasoning behind this change in direction is not known.

In addition to the main house, there would have been many service buildings. A stone structure was built prior to Clermont’s construction and was originally used as a kitchen; a stone loom house was added on to the kitchen a short time later.62 There most certainly would have been barns for sheep and other livestock, as well as for crops. Cassius stated that his father was “greatly in favor of secure shelter for his stock, grain, and hay.”63 Green also raised chickens, pigeons and bees; therefore, chicken houses, pigeon houses and an apiary for bees would have been necessary. Smokehouses, icehouses, outhouses, a cider mill and another mill house and slave housing would have also been situated on the property.64 In addition, Green Clay had a blacksmith shop, a carriage house, a harness house and at least one stone barn.65 Green also had two artesian wells bored so that the family and slaves could have clean water to drink.66

Floor plans of the second stage of Clermont. Floor plans and text description taken from Antebellum Architecture of Kentucky by Clay Lancaster, 1991. Courtesy of University of Kentucky Press and the Warwick Foundation.

The landscape surrounding Clermont would have included numerous crop production fields, undeveloped mature treed land for future timber use and formalized gardens with flowering plants, fruits and trees directly surrounding the family home.67 In referring to his ancestral home, a great-grandson of Green Clay, aptly named Green Clay as well, stated that Green and Sally planted trees and shrubs from “the mother state,” which can be assumed was Virginia, as well as tropical plants including lemon and orange “sprouts.”68 By 1820, the Clays had cedar and pecan trees and tulip beds.69 The finished home and lands would have been a showplace worthy of Green Clay’s station and status.

Given the vast expanse of Green Clay’s wealth, and the economic and political power that this man possessed within early Kentucky history, it is surprising that there is not more recognition of General Green Clay. He did get a Kentucky County named after him. There are eighteen counties in the United States named Clay County. Fifteen of those are named after Henry Clay. In the state Henry Clay resided in, the honor goes to Green, Henry’s first cousin once removed,70 who some speculate may have owned the entire county for which he was named.

No matter how wealthy and powerful, a man can’t live forever, and Green Clay developed a nasty case of skin cancer on his face, possibly from all those years surveying land under the ultraviolet rays of the sun. Green knew that the end was coming and got his affairs in order before his death. Youngest son Cassius served as a nurse to his father in his final days. On the night before he died, Green called Cassius to his beside, and gesturing toward the direction of the family’s cemetery, he stated, “I have just seen death come in at that door.” Those were the last words he spoke.71 The day of Green Clay’s death was October 31, 1828.

In his will, Green Clay imparted all of his land in Madison County, “some 2000 acres,” including the land on which the family home stood, to youngest son Cassius M. Clay. A common question asked is why did the youngest son get the family estate? By 1828, all of the older siblings had homes of their own. Sidney and Brutus had Escondedia and Averne, respectively, in Bourbon County. The daughters would have been settled as well in the homes of their husbands. Therefore, that left one child to inherit the house.

Among the interesting notations in the will regarding the home, Green Clay ordered that the paintings of himself and his wife remain hung in the house72 (he would be pleased to know that they are hanging in the house even today). Clay also tried to direct his wife’s life from the great beyond by stating that while she remained a widow, she could have the “west end on half of my dwelling house & farm where I live by a line running through the house, yard.”73 This leads one to wonder if Green indeed had a line drawn through his property. Hopefully, Sally’s half contained the kitchen and the outhouse.

In any event, Sally didn’t want anything to do with Green’s property or his will. She signed off on everything on December 1, 1828, separating herself from the legal document.74 A few years later, she married a minister (and, incidentally, her sister’s widow), Jeptha Dudley, and moved to Frankfort. This left Cassius and, by that time, his new wife a lovely home in the country with which to contend.