PART II

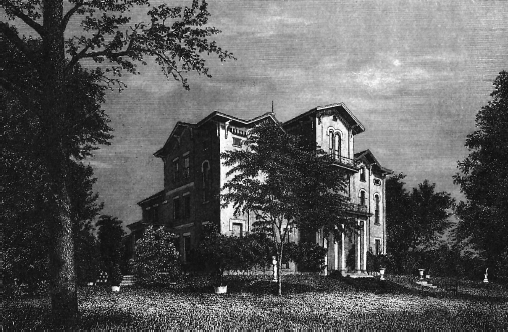

WHITE HALL

If a House Is Divided Against Itself

If a house is divided against itself, that house cannot stand.

–Mark 3:25, World English Bible

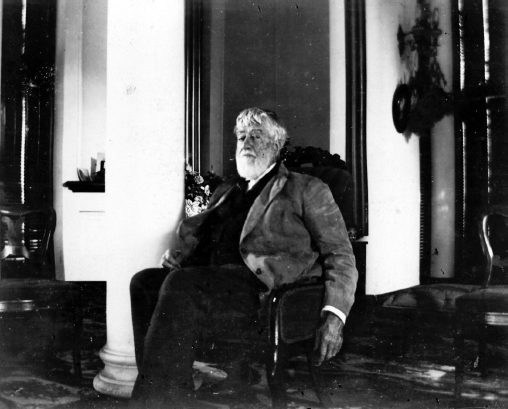

In some ways, General Green Clay and his son, Major General Cassius Marcellus Clay, could not have been more different. Green Clay was a wealthy tycoon—nearly everything he touched turned to gold. Cassius M. Clay lived his life trying to stay ahead of his debts. The father was a massive slaveholder, believing that slavery was a necessary means of doing business. The son felt that business would be better if slaves were emancipated. One thing they did have in common was a taste for impressive houses. Cassius, with his wife, Mary Jane, would eventually add on to the Clay family home, transforming the palatial country estate into a towering, eye-popping abode. However, before we get to the building, let’s look a little at the man (and woman) behind the mansion.

Cassius M. Clay75 led a charmed life. He grew up in an impressive home with a bountiful table and enslaved individuals to cater to whatever needs he and his family had. Cassius was well educated and was given the foundation at home to provide him with the financial security, social connections and extreme self-confidence to rise up in the world.

Clay’s rise to fame began with his educational studies. Perhaps because he had had so little schooling,76 Green was very generous with providing the means for ample education for his own children. Cassius stated that he attended a number of local area schools, as well as Danville College and Jesuit College,77 before going on to attend Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, and then later Yale University in Connecticut.78

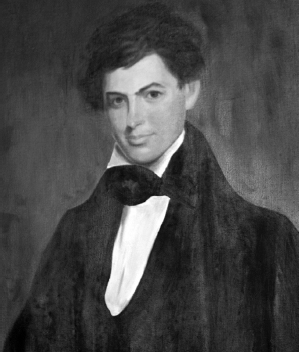

Portrait of Cassius M. Clay. This is a reproduction, which resides in the drawing room of White Hall. The original portrait was painted by Oliver Frazer and hangs in the Madison County Courthouse. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

While at Transy, Cassius resided in the main building on campus. On a Saturday night in May 1829, Clay was peacefully snoozing in his room while his male slave polished some boots on the stairs. The slave had placed a candle on the steps so that he could view his work but fell asleep without blowing out the flame, which soon tipped over and set fire to the stairway. The building went up in flames rather quickly. Fortunately, no one perished in the fire. Unfortunately, the building was destroyed. Such was the embarrassment of Clay over this incident that he never admitted any connection to this event until he was in his late eighties.79 It is believed that after the fire took place, having no dorm to live in, Cassius went to visit with the Todd family of Lexington. Cassius considered Robert S. Todd, the patriarch of the family, his “old and faithful friend.”80 One of the daughters, Elizabeth, would be a bridesmaid at his future wedding, and another daughter, Mary, would one day become the wife of a man Cassius and a great portion of the rest of the nation would respect: Abraham Lincoln.

Cassius also studied at Yale University but managed not to burn anything down. Cassius’s attendance at Yale would affect him in a major way and would influence Clay to devote his life to the antislavery pro-emancipation cause. What were the factors that played a part in Cassius becoming an emancipationist? The young Clay already had misgivings about the “peculiar institution,” for Cassius stated that he entered Yale with “my soul full of hatred to slavery”81 At a grass-roots level, it could be hypothesized that Cassius’s mother may have played a role in forming his opposition. Clay stated in his Memoirs that “at all events, the mother, being both parent and teacher, mostly forms the character.”82 One could also imagine that Cassius’s older brother, Sydney Payne Clay, had a great deal of influence, as he was also an emancipationist before his untimely death. There also were incidents that occurred that Cassius would have viewed growing up in a slaveholding family. Cassius stated that “my father being the largest slave-owner in the State, I early began to study the system, or, rather, began to feel its wrongs.”83

One incident that had a lasting impact on Cassius involved a family slave by the name of Mary. As a young boy, Cassius had been interested in gardening, and Mary assisted him in plotting out a garden. According to Cassius, a few years later Mary was sent to a separate plantation to cook for the whites, the “hands” and the overseer, named John Payne, and his family. Cassius stated that Payne verbally abused Mary, and when she objected, she angered not only Payne but also his whole family. The family sent her upstairs in their cabin to shell seed corn for planting. Mary was suspicious that something was up and hid a butcher knife in her clothes before she went upstairs. Meanwhile, the Payne family plotted a vendetta below. Eventually, the Paynes came upstairs and attempted to attack her, but Mary turned on them and fatally stabbed John Payne. At this point, she was able to make her escape and ran back to Clermont.84

In June 1820, Mary went on trial for the murder of John Payne. The trial took over a year and half to complete. At first, the court proceedings took place in Madison County, but after it was determined that Mary might not receive a fair hearing there, the trial was moved to Jessamine County. At one point, it was debatable whether Mary would live through the trial, as the horrid conditions of her jail cell compromised her health. A doctor was called in to examine her and provide an affidavit—for Mary to survive; she had to be removed from the unheated jail that was so open to the elements. It took Mary several months to recover from her illness. Throughout the trial, numerous witnesses were called for the Commonwealth, while many other witnesses spoke on behalf of Mary, including Sally Lewis Clay. This fact might lead one to suppose that the Clays believed their slave when she said that she had killed in self-defense. The trial finally came to a close in October 1821.85

Cassius M. Clay seems a little bit hazy on the actual proceedings of Mary’s trail; he stated in his Memoirs that Mary was acquitted of the murder, “held guiltless by a jury of, not her ‘peers,’ but her oppressors!”86 According to the official court documents, Mary was actually found guilty of murder and sentenced to execution on December 1, 1821. The pardon by Governor John Adair on November 13, 1821, was what saved her life.87

Although she was pardoned by the governor of Kentucky, Green Clay’s will instructed that she and a number of other slaves be “sent beyond the limits of this state” and sold “for the best price that can be had with a warranty that they non neither of them shall ever return to reside within this state thereafter.”88

At the time of Green Clay’s death, Mary was still fairly young. It is estimated that she would have been in her late twenties to early thirties and therefore could have had several more years in which she would have been productive in her service to her masters. Why then, was Mary still sold? Had Green Clay worked out a compromise with the governor? Was the stigma attached to Mary too great? Were there other factors that could have resulted in Mary being sold?

Perhaps its possible that Mary had a closer connection to Green than was openly known. In describing Mary, Cassius stated that “[s]he was a fine specimen of a mixed breed, rather light colored, showing the blood in her cheeks, with hair wavy, as in the case with mixed whites and blacks. Her features were finely cut, quite Caucasian.”89 In reference to his father and the possibility of a child out of wedlock, Cassius stated, “In the discipline of women, my father knew, as every sensible man knows, the strength of the sexual passions. Nature ever tends to the preservation of the races of animals. Opportunity, notwithstanding all the sentimentalism about innate chastity, is the cause of most of the lapses from virtue.”90 The possibility that Mary was an illegitimate child of Green Clay’s is not entirely unlikely.

Whether Cassius M. Clay remembered the exact proceedings of Mary’s trial is not as relevant as the impact his father’s will made on Mary’s life and, as a result, on his own life. Clay’s older brother, Sydney P. Clay, was executor of Green Clay’s estate. Although an emancipationist himself, Sydney was required to execute his father’s last orders. Cassius recalled his final time seeing Mary: “Never shall I forget—and through all these years it rests upon the memory as the stamp upon a bright coin—the scene, when Mary was tied by the wrists and sent from home and friends, and the loved features of her native land—into Southern banishment forever…Never shall I forget those two faces—of my brother and Mary—the oppressor and the oppressed, rigid with equal agony!”91

Certainly, the idea of antislavery had to have been introduced to a young Cassius before he attended any higher educational institutions. However, Clay credited the voice of the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison as being the straw that broke the camel’s back.92

It wasn’t just persuasive and influential people in his life who would have caused Cassius to go in this antislavery direction. Nor was it simply a morality issue with Clay. In his travels in the North, as well as his time at Yale, Cassius saw how business was done. The economy did just as well if not better in the New England states without the institution of slavery. Cassius believed that the South’s economy could do the same. In fact, he felt that the southern states could not continue with slavery and survive successfully in the future. Furthermore, Clay believed that slavery took away jobs from the working-class white population.93

Many people in the past and even today have called Cassius M. Clay an abolitionist. Clay personally objected to being called this, stating that it was “a name full of unknown and strange terrors and crimes to the mass of our people.”94 Cassius was undeniably an emancipationist. The two terms diverge in that an abolitionist believed that slavery should end all at once, by legal or illegal means (hence the Underground Railroad and other illegal practices of assisting slaves to freedom). An emancipationist wanted a gradual end of slavery. This measured autonomy would allow the slave owner to prepare economically for the loss of his or her property and also give the enslaved time to mentally adjust—emotionally and in terms of literacy and job preparation—before having the concept of independence thrust upon them.

Cassius felt that since the law sanctioned slavery, the law should then eliminate it, stating that “I consider law, and its inviolate observance, in all cases whatever, as the only safeguards of my own liberty and the liberty of others.”95 Clay practiced what he preached in regard to dealing with his own slaves. Although Cassius freed his own slaves, there were a number he could not liberate legally because they had been put into trust for Cassius’s children through his father’s will.96 Technically, those particular slaves belonged to Cassius’s offspring, and he did not have the right to legally emancipate them, and so these people were enslaved until freed by the Civil War. In a letter to the abolitionist Reverend John G. Fee in 1855, Cassius defended his actions:

I feel it my duty to keep my children’s slaves together and control them, rather than by disavowing any authority over them to allow the sheriff to hire them singly to the highest bidder. I have been in the habit of allowing them such privileges and wages as I think suitable to their condition as slaves, and the responsibility upon me for their support. I consider that I have done my duty when I have done all in my power to bring about legal and peaceable emancipation. Besides, I do not set myself up as perfect: far from it. A balance sheet of good against evil is all I aspire to.97

Cassius stated in his Memoirs, “I never sold a slave of mine in my life. The slaves sold…were trust-slaves—the title being in me only as trustee. I sold them for crime, as was directed in such case by my father’s will; and the proceeds were re-invested in lands, in Lexington, for the benefit of those for whom the ‘cestui qui trust’ was created.”98 In addition, Clay stated, “I never received a dollar from a slave of mine in my life. On the contrary, I liberated all the slaves I inherited from my father and thirteen others whom I bought to bring families together, or liberated at once…The buying and liberating of these slaves, half of whom never entered my service, cost me about ten thousand dollars.”99 It should be noted that although he claimed to have never purchased slaves on his own behalf (aside from those in which he was trustee), Cassius was not opposed to borrowing slaves from his brother Brutus when he needed them.100 Being a large slaveholder, Brutus followed more along the lines of his father Green’s philosophies when it came to the issue of slavery and did not subscribe to his younger brother’s ideals.

Cassius endured criticism and conflict not only from his peers of the white populations but also from his own slaves as well. At one point, Clay went to court over his slave, Emily, whom he believed to have poisoned him and one of his sons.101 Another time, Cassius went to court for shooting a former slave, Perry White, in self-defense. This altercation, nearly thirty years later, also stemmed from an alleged poisoning of a son of Clay’s.102

It may be difficult for those today to fully understand the extreme division and personal moral conflict that contemporaries felt at the time regarding slavery. When speaking a generation after slavery was abolished, Clay himself attempted to convey what it was like: “The present generation can know nothing of the terror which the slave-power inspired; but it can be faintly conceived, when a professed minister of the Christian religion in South Carolina said that it were better for him, rather than denounce slavery, ‘to murder his own mother, and lose his soul in hell!’”103 Cassius himself was Christian in faith, but he did have issues with churches and religions that touted slavery as a “divine institution.” In reference to those who believed as such, Clay stated, “I had no fellowship with men with such a creed; and I preferred, if God was on that side, to stand with the Devil rather; for he was silent, at least. So, if I said and wrote hard things against the Scriptures, and especially the preachers, it was because they were the false prophets which it was necessary to destroy with slavery.”104

It would be safe to say that educating the masses on the evils of slavery was a great love of Cassius’s. Another great love would be his first wife, Mary Jane Warfield. In every great epic, there is a love story. Many times, people will meet their future mate while at college, and such was the case with Cassius M. Clay. While he attended Transylvania, the second daughter of prominent Lexington physician and horse breeder105 Elisha Warfield caught the young man’s eye. Mary Jane Warfield had long, luxuriant auburn hair with large light grayish-blue eyes.106 She was graceful, had a talent for conversation and possessed a beautiful singing voice, and Cassius was so taken by her that before he left for Yale he gave her a copy of Washington Irving’s Sketch-Book with some sweet words inscribed therein.107 Upon returning to the Bluegrass Region, he visited her father’s home frequently enough to have Miss Mary Jane notice him right back.

Portrait of Mary Jane Warfield Clay by artist George Peter Alexander Healy. Courtesy of Catherine Clay.

It probably wouldn’t have been hard to notice Cassius, as he was somewhat of a looker himself, standing about six feet tall,108 weighing in at about 183 pounds109 and having fair skin, with dark hair and dark gray eyes (these genetics he attributed to his mother’s side of the family).110 The Cash man was also probably in tiptop shape physically as he enjoyed sports and was rather athletic.111 Sparks had to have flown across the parlor of the Warfield home, but it wasn’t until a hickory nut hunting party that they truly discussed their feelings for each other.

Cassius situated himself under the trees and made himself useful by hulling the nuts while others, including Mary Jane, went about gathering the bounty and dropping off their collections in a pile beside Clay. At one point, when other members of the party had wandered off, Mary Jane approached Cassius with her handkerchief full of the carya fruit, which she emptied onto the pile. When Cassius asked her to “Come and help me,” Mary Jane replied, “I have no seat.” Quick-witted Clay put his legs together and quipped, “You may sit down here, if you will be mine.” It’s doubtful that hickory nuts were the only things on Cassius’s mind when Mary Jane sat down on his lap, brushed his face with her hair and murmured, “I am yours” before flitting off to be with her friends. Cassius was left to wonder if Mary Jane’s technique was “simplicity, or the highest art?”112

It was like a scene from a movie. Some individuals at the time might have married for money, power or title, but it appears that Cassius and Mary Jane married for love, although there would be a few obstacles to overcome before they actually made it to the altar. One made itself known right after the nut hunting party ended. Cassius’s cousin, whom he refers to as Mrs. Allen, noticed the attraction, took the young man to the side and stated, “Cousin Cash, I see that you are much taken with Mary Jane. Don’t you marry her; don’t you marry a Warfield!” Mrs. Allen went on to list a number of eligible young ladies in the area whom Cassius could turn his attentions to, but to no avail—Clay was smitten.113

Another impediment to the star-crossed lovers was Mary Jane’s own mother, Maria Barr Warfield. In the grand tradition of intrusive mothers-in-law, she seemed to have hated Cassius’s guts. The trouble may have started when Cassius asked Elisha Warfield for Mary Jane’s hand in marriage rather than his future mother-in-law. Perhaps Maria felt that Mary Jane should marry a doctor like her father, or maybe it was in retaliation for the proposal slip up that caused Maria to give Cassius a letter written by a former beau of her daughter’s. Dr. John Declarey had said some unkind things about Clay’s character in the letter, and Cassius felt that he had to defend his honor.

What does a gentleman do in Clay’s time when he is insulted in a letter? Why, he goes and beats up the person who wrote the missive! Clay, with his “best man” James S. Rollins, traveled to Louisville, where the offending physician resided. While Rollins held bystanders back, Clay beat the tar out of Declarey in the middle of the street in front of his own hotel. Of course, Declarey responded with a challenge to a duel, which Cassius was only too happy to accept. The two men tried several times to get together to fight without large crowds following them but were unsuccessful, so Clay and Rollins headed back to Lexington, with Clay almost missing his own wedding. Thus under such drama were Cassius and Mary Jane joined in matrimony.114

Word would eventually reach Cassius that Declarey had boasted if he ever saw Clay again he would “cowhide” him (a serious offense at the time, reserved for such individuals as slaves). This caused Clay to again head back up to Louisville, but this time to do so alone. He again went back to Declarey’s hotel and waited for him in the dining room of the establishment. Clay was there leaning against a pillar when Declarey finally returned home. The doctor did not challenge Cassius but did turn a few shades paler and hurried away. Cassius hung out in Louisville for a few days after that hoping to drum up a fight, but Declarey never contacted him, so the newlywed returned home. Clay discovered later that the reason Declarey never communicated with him was because he was dead. The doctor had committed suicide by “cutting his arteries.” Perhaps the fear of actually going through with another physical confrontation with Cassius was too much to bear, or maybe dying was less of an embarrassment than getting beat up. In any event, Cassius never blamed himself for Declarey’s death, but rather Maria Barr Warfield.115 Pass that buck right along.

Although the marriage began with such a rocky start, Mary Jane and Cassius did enjoy (more or less) forty-five years of wedded bliss together. The marriage produced ten children: Elisha Warfield Clay (May 18, 1835–June 21, 1851), Green Clay (December 30, 1837–January 23, 1883), Mary Barr Clay Herrick (October 13, 1839–1924), Sarah Lewis Clay Bennett (November 18, 1841–February 28, 1935), Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. (1843–1843), Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. (1845–April 15, 1857), Brutus Junius Clay (February 20, 1847–June 1, 1932), Laura Clay (February 9, 1849–June 29, 1941), Flora Clay (1851–1851) and Anne Warfield Clay Crenshaw (March 20, 1859–1945).

Cassius and Mary Jane began their married life together with a seven-room brick home to make their own. It was soon decided that Clermont was a little too far out in the country. Lexington seemed a better fit for the young couple. Mary Jane liked being near her family, and Cassius liked being near the politics. The Morton House, located on the corner of Limestone and Fifth Streets in Lexington, looked like an ideal place to resettle. Cassius called the home “the most elegant in the city,”116 and he purchased it in the late 1830s for $18,000.117 The home itself was unusual when compared to other early Kentucky houses in that it was a brick home with stucco covering it.

While he was residing at the Morton House, Cassius began to set his sights on a political career. He studied law at Transylvania, and even though he was not interested in working in that profession (and actually never took out a license to practice),118 Clay could have been very successful had he chosen to go that route. A man accused of murder once asked Clay to represent him in court. The man allegedly killed his neighbor after the neighbor had given him a threatening look. Terrified, the accused claimed that he killed the man in self-defense. Upon hearing of the circumstances, Cassius’s “fighting blood was roused,” and he took the case. The prosecution brought forth the evidence, and it seemed cut and dried: the accused murdered a man in cold blood. Why should Clay even bother to present his side? Undaunted, Cassius quietly made his case and, according to one observer, “laid all the proof before them in a masterful way.” Near the conclusion of his arguments, Clay suddenly turned and gave the jury a chilling glare. The jury, alarmed by this sudden twist, recoiled in fright. Clay then asked, “Gentlemen of the jury, if a man should look at you like this, what would you do?” In response, the jury after a short deliberation decided on a not guilty verdict for the accused.119 Apparently, looks can kill.

The jury’s response to Clay’s glower is not surprising, since only an insane person would have wanted Cassius M. Clay’s temper directed at him or her. Over his lifetime, Clay became well known for not backing down from a fight. This characteristic became very public when Cassius began working on his career in earnest. Politics, antislavery speeches and fighting all seemed to go hand in hand in the 1840s for Cassius. While Clay did not reach the top in terms of political eminence, he was exceedingly talented in the other two departments.

When writing his Memoirs in his seventies and glancing back at his life and his dubious standing,120 Clay stated, “My reputation as a ‘fighting man,’ as the phrase goes, I have never gloried in. On the contrary, it has always been a source of annoyance to me; overshadowing that to which I most aspired—a high and self-sacrificing moral courage—where the mortal was to be sacrificed to the immortal. And, after a calm review of my whole life, I can truly say that I have never acted on the offensive; but have confined myself by will and act to the defensive.”121 Clay was always certain to act if he felt like his views or his (or his wife’s) honor were put into question.

Dirty politics is not a modern invention. In 1840, a rival of Clay’s for a seat in the Fayette County General Assembly, Robert Wickliffe Jr., brought Mary Jane Clay’s name up in an uncomplimentary way during a speech. Naturally, Cassius challenged this mudslinger to a duel. Upon hearing word of this fight, Cassius’s distressed mother, Sally, took pen in hand and wrote to him on August 2, 1840:

Cassius, My Dearly Blv’d Son.

You don’t know the anxiety I have felt since I heard you became a candidate last night. I heard there is a report in town that you and Rob. Wickliffe were expected to fight, altho I can’t believe it; still I feel unhappy knowing your disposition & sense of honour. How can a rational man think it honourable to disobey his maker’s law which says thou shalt not kill? How does it look for men to go out with their physician with them to try to take each other’s life and one kills the other? The survivor lives a miserable life here and without the sovereign mercy of God, dies and is miserable to all eternity! Oh! my son, think of the shortness of life and the vanity of all earthly fame. Surely you will not take it amiss for your Mother to exhort you to be upon gard [sic], you are very dear to my heart; there is no earthly tie stronger than the love an affectionate mother feels for her children; don’t be anxious, and if you are not elected show your philosophy that is more noble than vengeance, which the Almighty says belongs to himself. I hope the Lord will protect you: farewell. My love to M. Jane and the children.122

Clay eventually ended up dueling Robert Wickliffe. The two were spaced ten paces from each other and fired one shot with pistols, each one missing the other. (Apparently, the Lord did protect, as Clay’s mother had hoped.) Although Cassius wanted to try again, the seconds convinced him to let the matter rest.123

Even though Clay dueled with Wickliffe, Sally’s words did have an effect on him. At the bottom of her original letter, housed in the J.T. Dorris Collection of Special Collections and Archives at Eastern Kentucky University, Cassius penciled the words, “Note: This letter so full of good sense and coming from one whom I loved above all the world determined me never again to fight a duel: and I never have. C. 1884.”124 Cassius came to think of dueling as a waste of his time,125 and while a duel might have resulted in minor or no bodily harm, an actual skirmish with Cassius generally brought about serious maiming or death on the adversary’s part.

The battle did continue on between Cassius and Robert Wickliffe Jr. This time, instead of doing the fighting himself, Wickliffe chose to hire an assassin. The hit man was named Samuel Brown. Brown decided that his rendezvous with Cassius was to be on an August day in 1843. The location was a rally at Russell’s Cave in Fayette County. Perhaps the day was overcast, for Brown chose to make himself known first by calling Cassius a liar in the middle of Clay’s speech, then following that claim up with a hard rap against the offending man with his umbrella. Cassius was in the process of withdrawing his Bowie knife when Brown produced a more effective weapon—a deadly pistol—and fired at point-blank range at Cassius’s chest. In retaliation, Cassius took his knife and proceeded to carve Sam up like a Thanksgiving turkey. By the time he was done, Brown had lost an eye, nearly lost an ear, had his nose slit and his skull cleaved to the brain. A number of men threw nearby chairs and hickory sticks at Cassius, while others grabbed him to get him off Brown, though they knew that Clay would eventually get loose. To save Brown’s life, they threw him (Brown, not Clay) over a nearby stone fence.126

How did a man who had been shot at close range still defend himself to the point that multiple people were called to restrain him from his attacker? Brown shot his gun just as Cassius was taking his knife out of his waistcoat. Upon later examination, it was revealed that the bullet had hit the knife’s scabbard (which was lined with silver) and had become lodged there instead of in Clay. It would seem that Providence once again intervened for Cassius. Clay thought so himself, as he mentioned, more than thirty years later, “And when I look back to my many escapes from death, I am at times impressed with the idea of the special interference of God in the affairs of men; whilst my cooler reason places human events in that equally certain arrangement of the great moral and physical laws, by which Deity may be said to be ever directing the affairs of men.”127 It seems that Cassius felt God was certainly on his side in this particular fight.

In an odd and certainly unfair twist of events, it was not Samuel Brown, the paid hit man who threw the first punch and shot with intent to kill, who was put on trial for mayhem, but rather the victim of the attack, Cassius M. Clay. Cassius’s famous second cousin, Henry Clay, and his brother-in-law, John Speed Smith, represented him in court. Justice was on Clay’s side, as he was found not guilty.128 Although Clay extended the hand of friendship to his adversary, Brown never accepted the offer and was later killed in a steamboat accident. Cassius stated in his seventies that of all the men he fought in his lifetime, Brown had been the bravest.129

With his views concerning slavery, Cassius M. Clay was not the most liked man around. To add more flames to the fire, in 1845 Clay decided to start his own newspaper. Cassius had gotten into the habit of writing to the local newspapers on the subject of slavery, as well as his opposition to it. The newspapers were less than amused—Lexington being a major slaveholding town at the time and the surrounding areas also being very much proslavery—and stopped publishing the letters. This did not deter young Cassius one bit.

To ensure his freedom of speech, he established the True American, an antislavery newspaper that was published in Lexington and was so controversial that people were up in arms before the ink was wet on the newsprint. Clay received numerous threatening letters, one supposedly written in blood. It looked very much like a mob might advance on Clay’s office and take it down by force.130 His answer to this was to reinforce the exterior doors with sheet iron (to keep the doors from being burned) and outfit the office with an arsenal fit for war (including a number of guns, Mexican lances, two brass cannons and a keg of explosive powder, complete with match). The cannons were placed breast high and were stuffed with nails facing the direction Clay assumed the mob would be arriving. His plan, it is supposed, was that he (or some of his allies) would shoot the cannons at the enemy, light the keg of powder and escape out of trapdoor in the roof of the building.131 Clay believed in being prepared.

As it turned out, a mob did show up. Calling themselves the Committee of Sixty and for the most part composed, surprisingly, of Clay’s friends, the group was slightly more civilized than what Cassius had been expecting. This group secured a bogus court order from a sympathetic judge to stop the production of the True American. At the time, Clay was in bed sick with typhoid fever. He was forced to surrender the keys to his office and allow the group to go in and dismantle his press, which was shipped off to Cincinnati, Ohio. The newspaper continued production in that city, with Cassius editing it in Lexington.132 The newspaper was later purchased by the Louisville Examiner.133 Cassius ended up having the last laugh; he sued the secretary of the Committee of Sixty, James B. Clay (Cassius’s own cousin and son to Henry Clay—how’s that for adding insult to injury) for infringing on his freedom of speech rights and was awarded $2,500 for his pain.134 With friends like these, who needs enemies?

Photograph of the building that housed the True American printing press, located at No. 6 North Mill Street, Lexington, Kentucky. This building was razed at the turn of the twentieth century. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Clay’s approval rating among his peers was at an all-time low. Fortunately for him, the Mexican-American War was just beginning. Although Clay did not agree with what the war stood for (he felt, like many antislavery people at the time, that the war was an excuse to add more slave territory to the South), he suspected that he could potentially go to war and come back a hero. That is exactly what happened. In a capricious expression of their sentiments, the very same people who would have run Cassius out of town before he went off to the Mexican-American War had a parade for the man and presented him with a sword for his bravery in that war upon his return.135

So what did Clay do that was so heroic? He headed out in the latter part of 1846 with the First Kentucky Volunteers as a captain. Upon arriving in Mexico, he and his regiment were very quickly captured by the Mexican troops. The Americans discovered, much to their dismay, that not posting pickets results in the enemy successfully being able to surround and capture a target without a single shot being fired. When the Mexicans threatened to kill the Kentuckians after one of the captains escaped, Cassius reportedly stepped forward and stated, “Kill the officers; spare the soldiers.” A Mexican general came forward and, cocking his gun against Cassius’s chest, prepared to take him at his word. Undaunted, Cassius went on to say, “Kill me—kill the officers; but spare the men—they are innocent!”136

Apparently, the Mexican company was so impressed that it did not kill anyone. The company did, however, retain Cassius and his fellow soldiers as prisoners. On the march to Mexico, and also once under house arrest, Cassius did everything in his power to make sure that his soldiers and the others who were captured were as comfortable as he could make them. He sold his own belongings to do this, and Clay “expressed his regret that he was unable to do more.” One of the soldiers incarcerated with him stated that Cassius M. Clay was truly “the soldier’s friend.”137

Regardless of the fact that he was hailed as a hero by his fellow Fayette Countians, by the late 1840s Clay’s political career in that county had reached an end, and so Cassius and Mary Jane sold the Morton House in 1850, packed up the kiddies (by this time all but two of their ten children had been born) and traveled back to Madison County (where the political grass was a bit greener) and the family homestead of Clermont.

In 1849, Cassius began assisting antislavery candidates in their bid in the Kentucky Constitutional Convention. This convention would decide the fate of the future of slavery in Kentucky. Madison County allowed two delegates. One of the nominees, a local lawyer named Squire Turner, did not like Clay’s tactics. To be fair, when one goes to speak to the public, it is rather annoying to have another person there who rebuts everything one says. Cassius continued this irritating behavior until a speech at Foxtown. Normally, Clay went everywhere armed to the teeth, but this particular rally was near his home, and so he arrived with “only” a Bowie knife.

Squire got up to speak in a positive way regarding the slavery issue, with a few biting negative remarks aimed at Clay. To further infuriate Cassius, he went way over his time limit. Clay once again stood up right after Turner ended his speech to refute what Turner said and to complain that he did not have adequate time to rebut Turner’s speech. Turner’s son, Cyrus, took specific offense to Clay’s words, and when Clay came down from the table he had been standing on while speaking, Cyrus hit him. Clay drew his knife but was held off by about twenty men (interesting that it took that many), and his knife was taken from him. Clay was beaten with sticks and stabbed in the side, but he still was able to grab his knife back (he had partly grabbed it by the blade and cut two of his fingers to the bone in the process) and make his way to Cyrus, whom he stabbed in the abdomen. As seemed to be the case with Cassius, he once again made an apology to the man he had injured, and this time the apology was accepted. Cyrus Turner died soon after, and Clay took some time to heal from his wounds.138

Although there are numerous accounts regarding Cassius M. Clay’s eloquent speeches, his fiery temper and expertise in combat, little has ever been mentioned of Clay’s personal qualities, and what the man was like when he wasn’t behind a podium orating. In the examination of family letters, Clay revealed soft spots when he discussed his children to his wife, particularly the youngest, Annie.139 However, the only third-person narrative that the authors have ever found giving an insight into the family man that Clay was is a biography of Cassius written by his eldest daughter, Mary Barr Clay. Although Mary, like everyone else, does focus on the political realm that Cassius was involved with, she also gives some insight into the private man:

Father was very fond of flowers and music, and spent much money on us children for our musical education—uselessly, for none of us had much talent in that line. He was one of the most forgiving men, and generous to a fault. Living as he did surrounded by his enemies in our neighbors, some of whom sought his life. They would ask favors of him, and he never failed to grant them if it was possible for him to do so. We never knew from him who they were. He allowed us to go to their homes, and they came to ours, and never a word did he say against them. What we knew of them was told us by others. He loved fishing, and often went to the river back of our farm, and other streams, to enjoy the sport. On one occasion the men were having a barbecue on the river, and were out swimming, when Mr. David Willis became cramped, and while all the others were paralyzed at the danger of going near him, they called for “Clay” who was some distance off. He plunged in the water and seized him by the hair as he went under the third time, and brought him safely to shore, and saved his life.

He required strict obedience from us, but I remember only three times of his punishing us himself. Mother did that. A word from him was enough, as well as from her, generally.

My earliest recollections of my father was of his carrying the sick babies in his strong arms, and with a crooning song lulling them to sleep. He was the tenderest of nurses.

When we lived in Lexington, often when he came home from his printing office, he would take off his coat and get down on all fours and play horse, while we would climb upon his back, when the horse would suddenly rise up, or kick up and scatter children right and left. On one occasion I remember the servantman came ushering a gentleman, Mr. Charles Sumner, into the library, who no doubt was much amused and surprised at the performance.

We had a large cherry tree at the front door, and when cherries were ripe he would climb up and begin to eat them without throwing us any. We would call up to him to throw us some. He would say, “Dad’s sick.” We would begin to pelt him with sticks and grass until he was tired out, when he would throw us all we could eat. When at home from one of his speaking tours, when he wanted to take a nap, he often preferred to do so in the room where we were sitting, where our voices lulled him to sleep. He rarely used a pillow, but would lie with his arm under his head; he could sleep anywhere, no matter how hard or uncomfortable his position seemed to others.

His library adjoined our sitting room, and mother endeavored to keep it quiet for him to rest. He enjoyed reading Don Quixote, and would lie by the hour screaming with laughter over it. He was full of playing pranks on us children. He was particularly fond of the youngest ones, as he said: “The older one had too much will.” We would say in reply “like our Dad.” He loved to be with our young visitors, and always made himself agreeable to them.140

Cassius may have been an accomplished fighter, but through the eyes of his daughter, he was also a great dad.

There was a break from violent episodes involving Cassius for a time. He was still very active in the antislavery cause. One could say that a college was built because of his beliefs. Cassius had heard of the abolitionist Reverend John Gregg Fee and the persecution that Fee had suffered for his beliefs regarding slavery. Clay invited the minister to Madison County and gave him a tract of land for a house, as well as $200 in order to build it. In addition, Clay also gave Fee land on which to build a church and a school. The school would become Berea College, an institution where the white and black populations, be they male or female, could acquire an equal education. Founded in 1855, the organization became the first interracial and coeducational college in the South141 and is still a thriving college today that is one of a handful of educational institutions that offer free tuition to its students. Although Clay credited Fee with being responsible for the success of the institution,142 some acknowledgment should go to Cassius for providing the means by which the college got its start.143

Cassius continued on with his political rounds, speaking out against slavery at every meeting he could attend. Many times, doors were closed to him, so Clay took to speaking outside. Such was the case in 1856 in Springfield, Illinois. Cassius spoke for a few hours on universal freedom while Abraham Lincoln sat under the trees, whittling wood and listening.144 That was the first time that Cassius had met Lincoln, although he was a good friend of Lincoln’s wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, and her family. Of that first encounter, Clay always felt that he might have had some impact on Lincoln’s views regarding slavery, as he stated, “I sowed there also seed which in due time bore fruit.”145 Four years later, the two men happened to meet each other once again on a train. Cassius, never shy about his beliefs and also not one for brevity when it came to discussing his view on a subject, had a lengthy one-way discussion with Lincoln on the issue of slavery. After silently listening to Clay, Lincoln made the plain but pithy remark, “Yes, I always thought, Mr. Clay, that the man who made the corn should eat the corn.”146

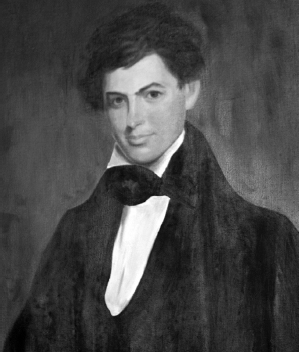

Both men were up for the presidential nomination at the Republican Convention in 1860. (An interesting side note is that Cassius M. Clay was a founder of the Republican Party.) Cassius was also up for a vice presidential nomination; however, Lincoln took the presidential vote for the party, and Hannibal Hamlin was the choice for vice president.147 Although not the popular choice, Cassius still did his part campaigning for Lincoln, and he was sure that once Lincoln was made president, a high political office would be his. Lincoln was victorious, but the hoped-for appointment was not immediately forthcoming. Cassius finally went to Lincoln and reminded him of all of the hard work he had done on the new president’s part. Although Clay was offered a ministership to Spain, he declined that post and eventually accepted the position of minister to Russia.148

Illustration of the candidates for the Republican presidential nomination at Chicago, taken from Harper’s Weekly, Saturday, May 12, 1860. Notice Cassius M. Clay in the bottom-right corner. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Although she stood by her husband, Mary Jane was not as excited over the prospect of a potential move. In an 1861 letter dated March 12, Mary Jane wrote to her sister, Katy, about the love she had for her home and her fears concerning her husband’s political appointments:

I have done all the gardening & other work in the grounds that can profitably be done yet awhile & am quietly writing to see if Mr. Lincoln means to appoint Mr. Clay to any mission, which he will accept. If he does, it will break us up here, I suppose, as all will want to go with him & the girls are heartily tired of country life. The place grows more beautiful & more dear to me continually & if I consulted my own pleasure I would remain just here. This a bright morning & the grass & evergreens look so beautifully. My fit flowers are as luxuriant as possible the birds are singing gaily, all nature is smiling! Ah! My own loved home, how my heart throbs at the thought of giving you up, well, we all must submit to circumstances, so I will not repine!149

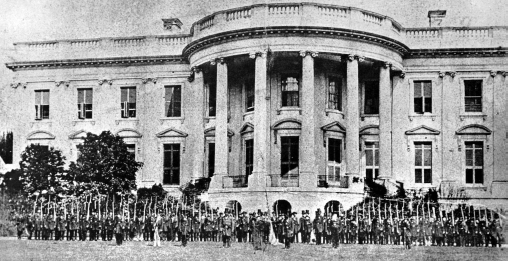

Submit to circumstances she did, for in the spring of 1861 Cassius, Mary Jane and five of their children were packed up ready to leave for Russia when there was a fear that the Confederate forces would overtake the White House. Cassius, with other men, formed a group of volunteers to protect the White House and Capitol. Called the “Clay Battalion,” the men stood guard until other reinforcements came in. Cassius was offered a military post at this point but felt that he could best serve his country (and himself) by traveling over to Russia.150 He did, however, accept the title of major general.

Photograph of the Clay Battalion, circa 1861. Cassius M. Clay is said to be the man in the foreground wearing light-colored trousers. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Unfortunately, Clay may have been a bit of an embarrassment to Lincoln and his cabinet. Cassius was outspoken as always, and on his stops to England and France on the way to Russia, he berated those two countries for being sympathetic with the United States South. Fortunately, Russia tended to think more along the lines of Clay, and he found the imperial Russian court very agreeable. Russia at the time was just coming out of an ancient feudal system. The czar at the time, Alexander I, had freed the serfs in 1861, right before Clay arrived in the country. Clay was very complimentary and worked very hard to be accommodating in hosting entertainments: “If they liked flowers I accommodated them; if paintings, I had some of the rarest; if wines I had every sample of the world’s choice; if the menu was the object, nothing was there wanting.”151 Although Cassius was enjoying his political office, Mary Jane was not so content. The cold, bitter Russian climate was not to her liking, and she was extremely homesick. It was decided that she and the children would return to the United States.

Cassius continued on as ambassador until 1862, when an embarrassment within Lincoln’s cabinet caused the president to recall Cassius to the States so that he could get Simon Cameron out of there to avoid further humiliation.152 Lincoln also put Cassius on a special assignment. Clay was to return to his native Kentucky and test the waters on a new policy Lincoln was thinking about that would later become the Emancipation Proclamation.153 At the time, Kentucky was a border state, was truly an area where brother was against brother, as portions of the state sided with the North while many others went with the South. Lincoln wanted to make sure that such a proclamation would not alienate Kentucky and cause the state to secede with the South.

At this time, Cassius also had a short stint in serving in the war. In late August 1862, General L. Wallace was in command of the Union forces. According to Cassius, Wallace asked Clay to take charge of the company after Clay made the suggestion that the troop plan a defense along the Kentucky River. Never one to back down from an opportunity that could put him in a position of grandeur, Cassius readily agreed and headed out of Lexington with the group of men and weapons. One can almost imagine Cassius shouting, “Follow me boys, I know the way!” as they headed toward Madison County.

Clay’s reign as commander was short-lived, as Major General William “Bull” Nelson arrived in Lexington, found out what was going on and rode in to take control of the troop. It is uncertain whether Clay took power because he was unclear about the chain of command, had the best interest of the company at heart or simply wanted his own wartime glory—possibly all three. In any event, Cassius seemed to take his demotion with grace, if a little disappointment.154 Had Cassius remained in charge of the infantry, the outcome would probably have been very different. Clay knew the region very well, and his expertise in this area would have provided an advantage for the Union troop. Instead, the company moved southward and became involved in one of the most definitive Confederate victories in the Civil War, the Battle of Richmond. In place of battle on the front, Clay went on to address the House of Representatives concerning the concept of an Emancipation Proclamation. Cassius reported back to Lincoln that Kentucky would stand with the Union should such a decree be made.155

Clay was appointed a second term as minister to Russia, and he returned to that country in 1863. In the middle of his tenure, word reached Cassius that Lincoln had been assassinated. He sent formal condolences to the first lady and continued on at his post until its successful conclusion in 1869. In speaking of Lincoln, Cassius stated:

Photograph of Cassius M. Clay in military uniform, circa early 1860s. Notice the sword at Clay’s side. This is the same weapon given to Cassius in recognition of his services in the Mexican-American War. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

We all know that Mr. Lincoln was not learned in books; but he had a higher education in actual life than most of his compeers. I have always placed him first of all the men of the times in common sense. He was not a great projector—not a great pioneer—hence not in the first rank of thinkers among men; but, as an observer of men and measures, he was patient, conservative, and of sure conclusions. I do not say that more heroic surgery might not have put down the Rebellion; but it is plain that Lincoln was a man fitted for the leadership at a time when men differed so much about the ends as well as the methods of the war.156

Clay went on to state:

But Lincoln was not only wise, but good. He was not only good, but eminently patriotic. He was the most honest man I ever knew. Lincoln’s death only added to the grandeur of his figure; and, in all our history, no man will ascend higher on the steep where “Fame’s proud temple shines afar.”157

Cassius was immensely successful as an ambassador to Russia. Clay had great respect for the leaders of that country, and this admiration seems to have been reciprocated. The greatest accomplishment Clay would achieve as minister was his effective negotiations for the purchase of Alaska from Russia for the United States. On March 30, 1867, Alaska would come under United States control, although it would be nearly ninety years before that territory would be admitted as an official state. Clay was justifiably pleased with his involvement in the acquisition and had said that if one thing could be placed on his tombstone, he wanted it to be the word “Alaska.”158 Sadly, this did not occur. What’s more, both his birthdate and death date are recorded wrong on his gravestone.159 Apparently, his children weren’t paying much attention.

Cassius served his second appointment as minister without his family by his side. It was decided that Mary Jane and the children would continue on in Kentucky. The younger children, Brutus and Laura, would pursue an education. The oldest son, Green, served overseas as well. The older daughters, Mary Barr and Sarah, assisted their mother and looked out for marriage prospects. The youngest daughter, Ann, was only four when her father returned to Russia; she spent time at home.

Portrait of Czar Alexander II. This was a gift given by the czar to Cassius M. Clay. Cassius had this painting on display in the formal reception hall, where it also hangs today. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

The family kept busy landscaping the yard around the original home. In March 1863, Mary Jane and her two oldest daughters were working hard. Mary Barr had a rockery built where a former building once stood, while Sally worked on having a pool dug. Mary Jane worked on leveling and grading the land around an old well, as well as the carriage road.160 This all was in preparation for construction to begin on an addition to the family home.

Cassius had set up working plans for his family home of Clermont to be enlarged while he was away. He chose for the architect and engineer Major Thomas Lewinski. Clay knew Lewinski as the latter had assisted Clay in protecting the True American.161 Although a fairly busy architect in the 1840s, by the mid-1850s Lewinski had secured a position as a secretary for the Lexington Gas Company, and by that time he was semi-retired and only ventured into the realm of architecture to oblige friends and former patrons.162

The builder was John McMurtry, one of Lexington’s most productive architects and builders.163 McMurtry had trained locally as an apprentice,164 and he liked to keep things interesting by building structures in various styles rather than sticking to one genre. Said to always have his black stovepipe hat and umbrella in tow, McMurtry was well qualified as he had supervised and built a vast number of homes and buildings in central Kentucky.165 Perhaps McMurtry had more of a hand in construction than just as the builder, for in 1887 he claimed that he “designed and superintended Gen. C.M. Clay’s residence.”166 Indeed, McMurtry is listed by name in a few Clay family letters, whereas Lewinski is not. It is possible that Lewinski simply produced the initial plans for the addition, and McMurtry took over with any changes that would have been made. Noted Kentucky architect Clay Lancaster thought as much, stating, “Lewinski and McMurtry had worked together closely on many projects, and it is not unlikely that the latter made more than a superintendent’s contribution to the final effect.”167

It is not known just how much input Cassius and Mary Jane had in the final appearance of their home. Most assuredly, Mary Jane would have kept Cassius abreast of each new improvement and solicited his advice. In addition, Cassius’s older brother, Brutus Clay, was an advisor to Mary Jane. However, in studying the structure, it is apparent that both the builder and the architect had strong influence on the finished product. The older home had been built in a Georgian style. The new addition would be built in Italianate.

Any knowledge pertaining to the timeline of the building of the addition would not have been possible for those researching the topic today had it not been for Laura Clay. Fortunately for contemporary researchers, Laura Clay, the next-to-youngest daughter, was away at school for the majority of the construction. Laura’s mother and siblings wrote letters to her to inform of the progress of the new addition. Although Mary Jane admonished her daughter to “never show any letters to anyone”168 and in at least a couple of instances instructed Laura to burn her letters,169 happily the daughter had a sentimental streak and saved them, so that a record still exists that offers a small window into the history of the house.

The foundation for the addition was laid in mid-April 1863. In a letter to her daughter Laura, Mary Jane mentioned, “I may not do more than build the foundation this year.”170 In January 1864, Mary Jane had been told by “the man who undertakes to put it up” (possibly this was Lewinsky or McMurtry or just one of their construction crew)—that the house would be under cover in August.171

Mary Jane had extreme faith in her builders. Many modern homeowners who have overseen the construction of a new house have had to endure endless waiting and dragging of the feet of the people they employ. Such was also the case, apparently, in the 1860s. Nearly a year later, in March 1864, the workmen were still toiling on the foundation. Mary Jane mentioned on March 13, 1864, that there were men at work on the foundation. At this point in time, to Laura she also hinted at the “beautiful improvements” that were made to the yard. However, much to the frustration and disappointment of these particular authors, she “will not mention them but let you enjoy them when you come home.”

Mary Jane also stated that the work on the foundation would be finished in two days, weather permitting.172 The weather must have not permitted. Those two days stretched into a month and a half. In an April 27, 1864 letter, the reader can really feel Mary Jane’s frustration when she wrote, “The stone masons left here last Saturday after working only one day & a half on the foundation & only a lick today, losing three days this week…I hope McMurtry will be here tomorrow.”173 Perhaps she was hoping that the builder would set a fire under the other workmen’s pants. He might have. A letter from Sarah to her sister Laura two days later stated, “The work on the house is progressing well. The workmen expect to finish the foundation of the house by the first of June.”174 The construction crew kept to this timetable, for on May 23, 1864, Mary Jane stated that the foundation “will be nearly complete next week.” It is apparent that after more than a year of dealing with the building, she became pretty burnt out, as she mentioned, “I am not so elated about it as I have been. I hope when Brutus gets here & I get rested some, I may enjoy the prospect of a house, as I have done.”175 Clearly, Mary Jane needed a break.

That break wouldn’t come. By early June, Mary Jane complained, “I have had in the last month as many as fifty men here at once in some way or another to be attended to.”176 By mid-November 1864, the first story had been completed, as Brutus Clay related to his sister Laura, “Ma is getting along slowly with her house, but the first story is finished, and she finds that she will have plenty of brick, which takes a great weight from her mind.”177 According to Cassius’s grandson, Green Clay, the clay used to make the bricks for the new addition was harvested from the very same pits that yielded the clay for the original house bricks. Green stated, “This accounts for the remarkable blending of color in the outer material used in the old and the new.”178 The brick was laid in American bond style, which would have been the easiest style of brickwork to lay. That’s a good thing, as the building would end up being massive. By early December, the second story was up, as the windows were being built in.179

In the early part of 1865, the family was still residing in Clermont while overseeing the work being done on the new addition. There was planning done in preparation for the finished home. Mary Barr did some research in Cincinnati, Ohio, for furnishings, carpets and fireplace mantels and grates.180 The completion of the second and third floors took place that year, for by October the family had moved somewhat into the new addition. Sarah wrote to Laura from the breakfast room of the home, stating, “The house is torn entirely to pieces, this being the only room in which I can have a fire.” Still, the family was making do in the unheated new section, as Sally (how Sarah was known to her family) stated, “We are all sleeping at present in the third story in mine and Mary’s room & without glass.”

Mid-October in Kentucky can get a bit chilly, and to sleep in bedrooms without windows might not have been ideal, as Sally commented, “You can imagine we are not perfectly comfortable however in a day or two we expect to come down into Ma’s and Pa’s & the nursery rooms which are now having the glass and grates put into them.” Although there were eleven workmen employed in construction at the time, “The house goes on slowly.”181 In December, Laura’s sister-in-law Cornelia (“Cornie,” as she was known to family and friends) wrote to her from the nursery, describing the progress that had taken place on the home:

Ma’s House is nearly finished it seems to me, and yet it requires some time yet to do all that needs doing. Ma says she will send the workmen away next week whether they finish or not, until the spring. The painters are here, but they have painted none of the inside work, nor will not this winter, except the library. The girls [in reference to Laura’s sisters Mary Barr and Sarah] are very anxious to have it finished that they may have a place to sit down in comfort.182

By the turn of the New Year in January 1866, the house had been completed enough for servants to be working in it. Sarah Clay related to her sister Laura that “Lucinda at five dollars cleans bed-rooms and nashes [Sarah probably means ashes, in reference to cleaning out the fireplace grates]. Amelia keeps the rooms down stairs and attends the table for eight.”183 A little later that month, Mary Jane was busy decorating and planning for the upcoming months. She told her daughter:

I am cleaning up around the house some & if I can continue at it for two weeks I will be much more comfortable. I hung the portraits [possibly of either her in-laws Green and Sally or of herself and Cassius] and candelabras in the dining room & library today & am very much pleased with the arrangement of them. I have Fullilove doing some jobs which the other carpenters left undone which is making me more comfortable. I must send for the workmen as early in Spring as they can work so as to have the house as nearly complete as possible by the time you and Brutus return home in June.184

Also in January, older sister Mary Barr was in Cincinnati, Ohio, purchasing furnishings for the new house. These items may have been the same ones she was researching the previous year, as among her purchases were bedroom furniture, rugs, carpeting and fireplace mantels.185

These mantels would be mainly for show. One progressive invention that was incorporated into the house was the central heating system. This was a concept that the family encountered while in Russia. Kentuckians at the time had to deal with messy, inefficient fireplaces—soot and ash would be everywhere. A great deal of the heat (but unfortunately not so much of the smoke) was lost out of the flues. Russia, being a colder climate, had perfected a heating system in order to adapt to the frigid temperatures. In a letter back to a friend, Laura discussed the appearance of the heating vents, which were adopted for White Hall: “The fireplaces are made in a kind of furnace which is made to resemble marble.”186 In addition, Mary Jane, while in Russia in 1861, wrote back to her sister Jule on the process of how the heating system worked where she was living, “The heat is shut off…a tight-fitting cap is placed over the chimney, a hole is opened in the wall of the room & the heat rushes from the chimney into the room.”187

This type of system apparently worked extremely well. Mary Jane stated, “In the morning the rooms are entirely pleasant to get up when one chooses without waiting to have a fire made.”188 In the same letter, Mary Jane also speculated on the construction of such a system, saying, “I suppose furnaces are built on the same principle tho’ & preferable on account of being in the cellar & only needing one fire for the whole house. Whether the heat can all entirely be thrown into the house or not is a question for me. Can it be or not? If ever we build I hope to have a furnace for the whole house.”189

Mary Jane’s hope became reality. The mansion had two furnaces that would have burned coal, wood or both installed into the basement. Ductwork was incorporated into the walls of the new section. The hot air was forced through this system into the rooms upstairs. Large openings, a lot like modern heating vents today, were in each room for the hot air to come through. There were fireplace mantels installed into the rooms, but these were faux and were too shallow to be used as actual fireplaces. All of the air would have traveled up out of one of two main chimneys in the house. The older section continued with the more archaic wood burning fireplaces.

Indoor plumbing was another modern amenity included in the home that either was influenced by the Clay family’s travels overseas or may have been a suggestion of Lewinski’s. This particular system was really ingenious, and it is believed to be one of the first of its kind in Kentucky. The plumbing was gravity fed. Water was collected from the gutters on the roof. It then traveled down through a pipe or pipes into a large storage tank, located on the third floor. From that cistern, the water passed through one of three pipes into three different rooms below on the second floor. The first room contained a toilet. The second room’s actual usage is not entirely known,190 but the authors believe to be a wastewater disposal area for chamber pots, dirty washbowl water and other similar refuse. The third room contained a bathing tub with a shower.

Although considered odd by modern standards, having three separate rooms rather than all of the bathing necessities in one room made great sense. The tank above could hold an immense amount of heavy water, and the three walls separating the rooms would help support that weight. Also, the three divided rooms allowed for more efficient usage of the spaces. One family member could use the necessities while another was able to bathe in privacy.

The incorporation of the indoor plumbing was completed sometime in 1866, or perhaps even later. The one reference that has been found concerning the system was made by Mary Jane in an April 27, 1866 letter to her daughter Laura. In the letter, Mary Jane mentioned that she “will go on to complete the house as fast as I can get the workmen to do it, except the cistern & bath room & closets connected with it. We can be comfortable without that being done so will wait on more convenient season.”191 As accustomed to modern indoor plumbing as contemporary society is, perhaps this statement might not seem to make sense. Virtually no one today would consider a home complete without a functioning bathroom. The Clay family, like most people up until this point, would have used portable baths, called hip tubs or hip baths, for bathing. (The newly installed permanent bathtub would be much larger than these more moveable baths.) Answering nature’s call would have been done in a small building or buildings located behind the main house (referred to as the “Mrs. Jones” by one Clay daughter).192 Should the need arise in the middle of the night or on some cold and snowy day, one could also employ the services of chamber pots, which the Clay family most certainly had. The indoor bathrooms were definitely a luxury, not a necessity.

It is a common misconception of modern society that those in the past did not bathe regularly. Personal hygiene at that time had a lot to do with opportunity, social standing and one’s own viewpoints concerning the subject. Mary Jane wrote to her daughters admonishing them to be clean and to change their underclothes regularly.193 In addition, the family felt that a cold bath was good for the constitution.194

A unique feature to the home is the number of closets the house contains. It was not a normal practice for a home in the 1860s to contain closets. Most people at the time stored their clothing and linens in wardrobes or armoires. The mansion contains two closets in nearly every bedroom, and the master bedroom contains three closets. All together there are seventeen closets in the home if one includes the bathroom spaces as three separate closet spaces, and Mary Jane did, as she refers to them as closets.195

The actual usage of the bedroom closets is unknown, as the Clay family is surprisingly mute on the subject. One can make educated guesses as to the purpose of such rooms. The closets could have been used like one does today, with the spaces being for clothing storage. Perhaps Mary Jane was making a reference to this when she told Laura in a May 1864 letter, “After a while we will have plenty of room for our clothes. Will that not be charming?”196 White Hall does not have a useable attic, and so the rooms could have been for extra storage. When traveling in the 1860s, one did not use the small and efficient luggage that is a staple of today’s society. Instead, large trunks would have been utilized. A portion of the closet space could have been employed for the storage of these traveling chests. Also, at the time, if one had personal slaves, those slaves stayed near a person, even at night, in case the owner needed anything. The rooms are large enough to have been a sleeping space for a person.

In the spring of 1866, Mary Jane was still busy working on the outside features to the home and yard. In March, Mary Jane moved the yard gate at McMurtry’s suggestion. She was “delighted” by its placement. The new addition essentially was built above and around the former house, keeping Clermont intact by literally wrapping around the original structure. The southern-facing porch to the main entrance of Clermont was enclosed in glass and made into a conservatory or sun porch. The main entrance to the new addition now faced east, a fact that Mary Jane was proud of and pleased with. She stated, “The yard appears to fine advantage which it never did before & the house produces a much finer effect, from the side toward Green’s. [This is in reference to Mary Jane’s son Green Clay’s farm.] The house appears to greater advantage than any other position & from the lumber house I think it is beautiful.” At this same time, Mary Jane was also working at removing all of the litter made by the building from around the mansion and was in the process of getting brick and stone to lay out the carriage path. All the work and hassle had been worth the wait; she went on to state, “I do enjoy my house so much, even in its unfinished state, it is a pleasure to me.”197 Later, Mary Jane gushed, “I am now delighted with my yard for the first time. The change in the entrance is the greatest improvement. It is beautiful!”198

Despite her delight, Mary Jane was still working with both ends of her candle burning. She became worn down from all of her responsibilities and confided to Laura, “I hope your Father will be content to come home & attend to his peculiar duties & allow me to attend to mine only, for which I would be truly thankful.”199 In April 1866, she relayed to Laura, “I am so weary, or lazy, or something, that I do not feel inclined to go out of the yard at all & I feel all the time that I will rest myself after each job is completed but each one is so long being completed that other things are pushing to be done continually.”200 In another letter, Mary Jane seemed close to despair when she said, “Oh! My life is all toil!”201

In addition, Mary Jane felt that she could not deal with the family business as she should when her attentions were devoted to the progress on the house and yard. In another letter, also written in March 1866, Mary Jane related:

I am very busy having the yard cleaned & laying out the carriage drive. I feel that I am neglecting every business to this pleasure. I feel that I am getting lazy about business & it is becoming very irksome to me. I am yet without workmen but am anxious to have the stonemason come & finish the work & would like the plasterer to come as soon as practicable to finish his job. Sally wrote to your Pa to send us carpeting for all the house & he answers that he will so perhaps we may get the house carpeted. If he can do it without going into debt I will be very glad for it would be very uncomfortable looking to have naked floors for years. I shall add furniture very shortly. I feel very comfortable now, I suppose it is the result of having been so uncomfortable for so long.202

The drudgery continued for Mary Jane: “Feely & two other stone masons are here at work & I believe all the stone work will be completed next week. Then I will send for plasterers & then another stone mason to lay the floor of the vestibule & portico, after which I do not calculate upon having any other workmen.” Even without outside workers, Mary Jane intended to keep going: “I may be able to get the pantry papered & painted this spring but will attempt nothing now. Your Father will send some carpeting for halls & stairs, all other furniture we can do without & will furnish as we can afford it.”203

She may have been weary, but Mary Jane still enjoyed watching the progress on her home. She mentioned in a late April 1866 letter, “I am much entertained just now in having the terraces made by two good Irishmen & Jerry is dressing up the walks & flower beds.” She added, “I will have these Irishmen to lay stone on the carriage drive as soon as they finish the terrace & clean out the cellars.” She concluded, “It is all beautiful and delightful; if I can afford to keep it in order, I will be much gratified.”204

The reader can glean from just these excerpts of letters that money was an issue for the Clays. Viewers today of the palatial mansion might get the impression that the family had an endless supply, but this was not the case. Cassius did get a stipend as minister. This he used where he could at home, but he was also expected to maintain a certain standard as a United States ambassador. In one such letter, Cassius related home to his wife, “I do deny myself a great many things here: but you must remember that the government give me a certain salary to maintain a certain degree of respectability here: which I cannot forego by turning every thing to private account. Almost all ministers from our country spend salary: and private fortune both.”205

In this letter, Clay also denied a pleasure trip for their daughter Sally, stating that he didn’t think it was prudent of Mary Jane to spend money on something so frivolous “when you have not a bed hardly to give her, when she is married!”206 He needn’t have bothered; Mary Jane knew that the bills were accruing. Family letters are peppered with references to money and making “ends meet.”207 One way was to sell cash crops and raise livestock in the effort to bring in more money. In an undated letter (probably circa 1866), Mary Jane bemoaned to Laura, “I sent my sheep to market & did not get half as much money as I expected from them and as I have still such heavy bills to pay for erecting our home it greatly distresses me for I have yet to furnish it, which I despair of doing so for a long time yet.”208 There was the prospect of a lucrative investment in the oil industry; in the same letter, Mary Jane mentioned that “I am now hoping for a great, great success in our oil speculation. If it succeeds, all will go merry as a marriage ball. Hope is a great comforter.”209 Hope was all she had, for although other letters between family members mentioned the wished for oil payday, it must have never occurred. There is no record of the Clay family striking it rich with the “black gold” or “Texas tea”—or of them “moving to Beverly.”210

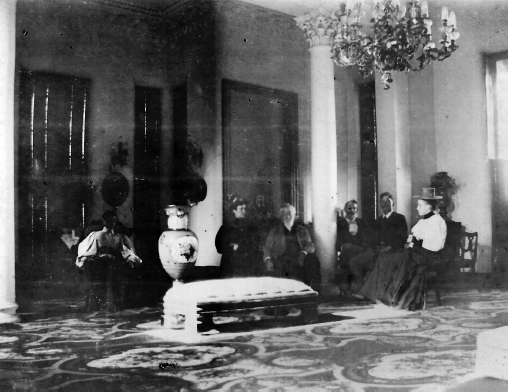

By the late 1860s or early 1870s, the mansion would have been on the back end of completion. It took nearly a decade to finish and transformed a modest seven-room home into a forty-four-room mansion. Any guest visiting the estate would have been greeted by two massive wooden front doors that opened to reveal a main hallway large enough to intimidate horizontally and vertically, with its stretching length and sixteen-foot ceilings complete with decorative frieze work. The curving main staircase leading to the second floor would have evoked admiration in all but the most jaded of callers. To the side of the staircase was a room made to access the space underneath the stairs. Perhaps this could have been employed as a cloakroom or general receiving area, as this smaller space was also meant to impress, with plaster frieze work in a fruit pattern incorporated into the ceiling decoration.

Should one be so lucky, the visitor might be invited into the awe-inspiring drawing room, which continued with the sixteen-foot ceiling height and included two towering Corinthian columns, with decorative plaster frieze work located on the upper portion of the pillars, encircling the entire ceiling, as well as a medallion above the chandelier. A back hallway that included a staircase leading to the second floor, a set of stairs that went to the basement and a small closet would have been hidden from view by a massive door. Originally, the house had a parlor, a dining room and a study or second parlor on the first floor. At completion, the parlor was turned into a dining room, the study or second parlor became a library with floor-to-ceiling glass-covered bookshelves and the old dining room became a breakfast room and pantry, with a closet added in the southeast corner of the room.211

If the visitor was an overnight guest, he or she would ascend the stairs and would have probably spent a pleasant evening in one of two impressively sized bedrooms, each with a pair of walk-in closets, and he or she would have been able to utilize the modern three-closet bathroom in the back hall. Transom windows were placed over each of the bathroom doors to ensure adequate lighting and airflow. The more private second floor to the old home had been updated as well. The master bedroom, referred to as “Pa’s” (Cassius’s) room in multiple letters,212 was nearly tripled in size. A wall was removed between two rooms that had been bedchambers previously, providing a roomier space. Three large transomed closets were added in to the existing original master bedroom, and a large retreat room was incorporated onto the backside of the main staircase and faced the front side of the mansion. The remaining two bedrooms on this floor seem to have not been altered a great deal.

As mentioned previously in a letter, new glass and fireplace grates were installed in the bedrooms. In addition, the stairs that would have led up to the original attic were removed along with a window that would have been in the original hallway. This slightly enlarged one of the bedrooms, while the third room remained the same size. To reach the attic space, the guest must exit out of the old section of the second floor and travel up a flight of back steps. The attic was transformed into two large rooms. One room had the ceiling raised to a higher level, with new windows installed, while the other room maintained the lower ceiling with sloping sides that would have reflected the original roofline. Because of the low ceiling height, this room could have potentially been used as a storage space.