PART III

ABOLITION

This House Lies in Ruins

Is it time for you to live in your paneled houses while this house lies in ruins?

–Haggai 1:4, God’s Word Translation

One could imagine that the morning of October 8, 1903, in northern Madison County, Kentucky, dawned clear and bright with Indian summer warmth. A large group of local and not so local people gathered on the Clay family’s palatial estate in the hopes of claiming a piece of the old fiery general’s personal effects. It had been part of Clay’s will that he wanted his possessions to go up for auction,307 so perhaps Cassius would have approved of the large crowd and the number of items that went up for public sale, so many in fact that it took two days to auction off all of the pieces.308 A twenty-four-page typed report of the sale list made by the State Bank & Trust Company (administers of Clay’s estate), which recorded each of the items, showed that the grand total for the sale was $3,653.309

Clay’s most impressive possession, however, was not available for purchase until two weeks later. On October 22, 1903, just a few days after Clay would have turned ninety-three, had he still been living, White Hall was put on the auctioneer’s block along with the surrounding land. Some might question why the home was not given through Clay’s will to a descendant. Clay left his remaining heirs in quite a tizzy when he died, as he had as many as six wills floating around at his death.310 Some were very similar to one another, with only minor changes. Others were very drastic in the differences. Dora Richardson Clay Brock wanted her share of the pie and took Cassius’s children to court over the wills, as a few of them were very generous to the former Ms. Richardson,311 a fact that Clay’s children were not happy about. The wills were eventually declared null and void by a judge, with the property to go to Clay’s “natural heirs.”312 After many months of lawsuits and court dates, Dora had to concede to the biological children and slink away with nothing more than some wasted time to show for her efforts.313

Despite the battle in court over Cassius’s estate, White Hall mansion proved to be a large deteriorating structure that none of the children had a desire to obtain or restore. It was a descendant who would acquire ownership of the towering domain. Cassius’s grandson, Warfield Bennett Sr. (Sarah Lewis Clay Bennett’s son) purchased the mansion and 360 acres of land that surrounded the home for $30,060.314

As a young boy, Warfield had visited his grandfather Cassius and took the necessary precautions, lest his grandsire mistake him for a trespasser of the vendetta nature. Crawling on his hands and knees up the last part of the driveway, Warfield would shout, “Don’t shoot, grandpa, it’s me, Warfield!” Decades later, Warfield’s granddaughter, when discussing the relationship her grandfather had with his own grandfather, Ann Bennett commented, “I got the feeling they were fond of each other, which may explain Warfield’s love of the old place.”315

Although a successful bank commissioner,316 Warfield was a farmer at heart, and he may have purchased the home for sentimental reasons, but the main motivation was more than likely the prime real estate that surrounded the house. Bennett used the land purchased for tobacco cultivation (a very lucrative cash crop at the time), along with other cash crops such as wheat and corn. Bennett also followed in the footsteps of his grandfather Cassius and great-grandfather Green and raised sheep on the property, as well as pigs.317

While the land surrounding it was rich and productive, it appeared that the mansion’s glory days were over. The building was not in great condition; Cassius had not given his home the tender loving care in his later years (or, being the big money pit it is, the massive continuous upkeep) that it needed. After Warfield purchased the home, he only provided minimal maintenance. The older Clermont section of the first floor and the 1810 addition on the back were used as living quarters for various tenant farmers. The impressive drawing room, once the setting for grand parties and entertainment, became agriculture storage space for hay bales and feed sacks. More hay bales were stored upstairs in the massive bedrooms and hallways.318 The daunting first-floor reception hallway, which once awed Clay’s visitors upon their arrival, now served as a garage for a tractor.319 Although many guests today, upon hearing what became of the mansion in these years, express surprise, disbelief and sometimes disdain, it should not be thought of in such a way. Warfield simply used the house any way that he could, and it makes sense, given the large size and the advanced level of deterioration, that the home was used as a barn.

It should not be misconstrued that Warfield Bennett was happy with the way his ancestral home was turning out. In an interview nearly fifty years after his purchase, when asked about the derelict state of the house and surrounding land, he stated, “I can’t think of it, can’t let myself.” In that same interview, he expressed a desire to be younger and more able to oversee the farm’s production like he once did.320

Ann Bennett, a great-great-granddaughter of Cassius M. Clay and granddaughter to Warfield, described the visits when her grandfather would allow her to walk around the dilapidated old mansion:

We would get to come out to Whitehall when we visited, if we were lucky. I remember it being quite an adventure, driving the old road, pulling up in front of the enormous house. We would be watched closely and be instructed to be very careful not to fall through the rotten floor boards or touch the crumbling railing on the stairs. We couldn’t even think of going upstairs—I think some of the railing had been burned for heat by poachers or transients that had spent some time in the old place. There were wasp nests and bats and lots of trash…There was a sadness about those visits too—the few there were—in that the place was “too far gone” to ever be “saved” my grandfather said. As a child, the whole idea that something grand could just slowly fall down and that would be the end of it, was a lot to grasp. I remember feeling the sadness, but then not thinking too much about it, just accepting it.321

Sadness is what many people conveyed when they walked around in the empty, echoing halls. A guest to White Hall once told the author that her father owned a farm behind the Bennett property. He visited White Hall once and came home with tears in his eyes, saying, “Somebody needs to restore that place.”322 Another individual who visited the mansion when abandoned made the comment, “It makes you feel like you’re walking on land where you shouldn’t be.”323

The house was not totally empty. Tenants resided in the house from right after the mansion was purchased at auction in 1903 to the mid-1960s. Numerous families lived in the house in the older section of the first floor in the main house, as well as the old kitchen and cook’s residence off of the back porch.

Photograph of White Hall showing the original Clermont side, circa 1940s. Tenants would have resided in this back area. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Judy Ballinger King, a former tenant of White Hall, visited with the curator and described her time of residence in the mansion. Judy, her parents and grandfather occupied White Hall in the early 1950s, when Mrs. King was five and six years old. The Ballinger family resided in the former library and pantry of the mansion. There was no electricity; instead, coal oil lamps and a coal stove were used.

Judy was an adventurous little girl:

I would get out and roam this house, I’d be gone all day. I wasn’t afraid. I would get out and ramble all over the place. I would get lost a lot of times and couldn’t find my way back down, that’s why I’d stay up there just about all day. The only time that I think that I almost panicked it was getting late in the day and that’s when I couldn’t find my way back downstairs because I would get lost up here; there was so many rooms.324

The only area in the mansion Judy did not like to visit was the basement. In her words, the area was “cold, damp, dreary and depressing.” She recalled the manacles in the jail cell being on two of the walls.

Judy could have quite possibly been White Hall’s first docent. She certainly would have been its youngest and sweetest. Visitors would hear about White Hall and drive out to the gate of the property. Judy would volunteer to take them through. After a story ran in a local newspaper, with images and information about White Hall, Bennett put a stop to the impromptu tours.325

Although a portion of the great mansion was inhabited, this did not stop trespassers from stopping by and snooping, with or without a tour guide. Life at White Hall was not always a quiet and private venture for the tenants. Thrill-seekers would make unannounced house calls. Some visitors would reverently walk the echoing halls and depart without a trace, while others would leave their names on walls to prove that they had visited.326 Some would do extensive damage to the site, in one case burning the banister of the grand staircase.327 Still others would attempt to pilfer a relic. On one such occasion, in the occupancy of the last tenants to reside in the home, uninvited guests stood on the front portico of the mansion attempting to chip away at the brick and marble in order to pocket a token of their visit. When advised by a tenant that they not deface the structure, a gun was pulled on the resident.328

Photograph showing the front porch of White Hall, circa 1951. This photograph was originally published in the May 31, 1951 edition of the Lexington Leader. Seen in the photograph are an unidentified person and tenant Judy Ballinger on the tricycle. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Fraternities from the local colleges and universities were also uninvited guests at White Hall and made visits part of their activities. One guest while on tour with the curator mentioned that when he attended school, it was part of the initiation to travel to White Hall and take back to his organization a spindle from the main staircase to prove that he had been “brave” enough to visit the haunted old house.329 Another guest recounted how she knew of different college organizations that would drive their initiates out to the mansion, drop them off and make them find their own way home. In her words, “Everyone was out there but who should have been out there.”330

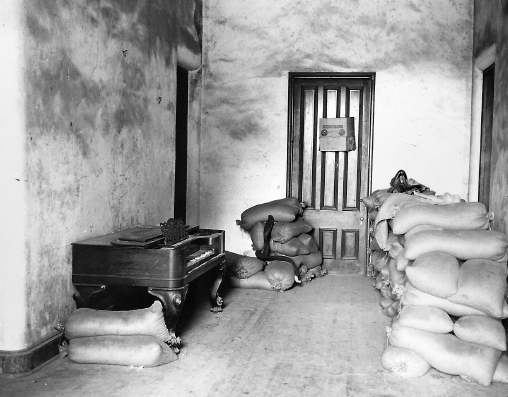

Photograph of the formal reception hall, circa 1950s. The piano seen in this image is surrounded by feed sacks. The instrument is a patented 1859 Steinway and is the only artifact to have resided in the mansion since Cassius M. Clay’s death; it has never left the building. Supposedly, when restoration took place, a family of chickens had been roosting inside of it. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Sometime in 1965, the last tenants moved out of the mansion, leaving the huge house to deal with the elements and vandals on its own. The house was suffering a slow and agonizing death. The home, like the great man who once lived there, was fading from history.

Yet it would seem that some people had not forgotten White Hall. In 1965, the Richmond Garden Club began a crusade to get others in the community involved with the restoration of the deteriorating mansion. On one visit to the decaying manor, one club member, Betty Cox, cajoled her husband into visiting the site with her. Since her husband, James, was a professional photographer, she persuaded him to take pictures of the estate. This he did with an eye of an artist, focusing not only on the heartbreaking destruction that had occurred but also the beautiful architectural details that still survived.

Mr. Cox had heard stories about Cassius M. Clay since he was a boy. One of his first experiences involving Clay was studying the man while in the sixth grade. Excited about the stories concerning Cassius and his involvement with freeing the slaves, Cox went home to relay the tales to his mother. His mom replied with, “We don’t talk about him; he wasn’t a good man.”331 Many of the older generations who could remember Cassius or had heard stories from their parents or grandparents had very jaded opinions of the man. Despite a less than positive reputation, there were those who still admired Cassius. Perhaps it was evoked admiration that inspired Mrs. Betty Cox and her husband to become concerned about White Hall and its downfall.

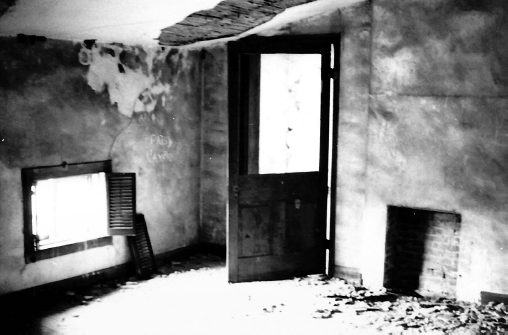

Photograph of the drawing room, circa 1950s. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Photograph of the library, circa 1965. The mantel in this room is one of three surviving mantels in the mansion. Notice the wallpaper that had been placed over the glass bookshelves and the stovepipe hole in the wall, both remnants of when tenants resided in this room. Courtesy of James M. Cox.

Photograph of the grand staircase in the formal reception hall, circa 1950s. Vandals would later destroy the banister, newel post and spindles. Notice the canvas tarp stored beside the stairs. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Photograph of the master bedroom, circa 1965. The mantel in this room was one of three to survive. Notice the wallpaper on the walls. This is believed by the authors to be original wallpaper to the mansion. Unfortunately, it was not saved. Courtesy of James M. Cox.

Photograph of a third-floor bedroom, now known as the history room, circa 1965. Notice the ceiling is in terrible condition, and the fireplace mantel has been ripped out. Courtesy of James M. Cox.

The Coxes would visit White Hall frequently and would notice how pieces were gradually being taken out of the mansion. Mr. Cox remembered viewing the original lining in the bathtub. He recalled, “Then later we came out, like another month, and someone had stolen it, ripped it out.” Door hinges and locks suffered the same fate. Another visit found Cox attempting to enter the basement, which was so full of trash that he could not go in from the outside area but instead had to proceed through another entrance. Mr. Cox stated that he feared that the house was in danger of burning down. 332

Since a picture truly is worth a thousand words, the authors will not continue discussing the downfall of the mansion but rather will allow the readers to examine the damage for themselves in the images in this chapter.

As clearly shown by photographic evidence, the mansion was in dire need of restoration, promptly, before more was lost to the ages. Help was on the way.