PART IV

RESTORATION

From the Ruins I will Rebuild It and Restore Its Former Glory

In that day I will restore the fallen house of David. I will repair its damaged walls. From the ruins I will rebuild it and restore its former glory.

–Amos 9:11, New Living Translation

When the great pass from flesh and blood into history, we often forget that there once were very human souls behind the heroic veneer that time and distance have built.”333 Such was the case with Cassius M. Clay and his illustrious White Hall. The humanity and life would soon be returned to this great man and his house through the efforts and cooperation of many dedicated organizations and individuals.

As previously mentioned, the Richmond Garden Club worked hard to focus attention on White Hall so that restoration could take place. According to Mrs. Helen Chenault, who was president of the club at the time, a number of the members had attended a tea in Louisville on October 5, 1965. On the return trip from the event, the ladies made a stop in Frankfort to speak with the Kentucky Historical Society. The director of the society, Colonel George Chin, was very reassuring and encouraged them to proceed with their efforts.334

In order to get the general public to notice the mansion, and perhaps contribute donations and enthusiasm for restoration, the Richmond Garden Club hosted a flower show that 1,500 people attended. The ladies used their expertise in arranging flowers to symbolize and highlight the beauty of the arrangements as opposed to the destruction of the site. They included whatever they found on the premises in their designs; one lady incorporated a hornet’s nest she had found at White Hall into her display.335

The club also met with numerous directors of historic sites, as well as various organizations such as the Civil War Round Table, in order to gain insight into what was needed and to build up interest.336 At one point, members enlisted the assistance of the head architect from Colonial Williamsburg, Walter Maycromer. This knowledgeable gentleman arrived one day and perused the mansion and grounds with the ladies. When touring the mansion, Maycromer was enamored of the mantel in the library and commented that it was “the finest example he had seen.”337 He scraped paint off of the wall in the original parlor until he reached a layer of blue paint tinged with green. Mr. Maycromer was positive that this was the original coloring of the paneling. Outside the mansion, Maycomer took a staff and penetrated the soil around the buildings to determine where original walkways would have been located. He made his way down to the stone building behind the mansion and examined it. He was sure that the ten-foot opening to the fireplace was the largest still in existence.338 The Williamsburg representative was very encouraging and would have gone on to further assist in the restoration process had he not passed away a few weeks later.339 Although this would be a disappointing turn of events, in the end the club’s aid would come from a more powerful source.

William H. Townsend was a lawyer by profession and a historian by interest. He had read a little about the fiery Cassius M. Clay and thought that Clay was the perfect subject for a Civil War Round Table speech he was to deliver to an audience up in the Windy City. In 1952, Townsend gave his oration, entitled “The Lion of White Hall.” In this lecture, Townsend colorfully presented Cassius’s life in an entertaining way. His talk was so well received that it was recorded and sold to the public. Although the speech did breathe new life back into the history of Clay and got numerous people interested in this great man, it should be noted that the speech is chock full of inaccuracies. Townsend himself once stated that he “never let the truth get in the way of a good story.”

In an effort to present Cassius M. Clay as a larger-than-life narrative, he added in information that was not entirely correct. In reality, the true stories surrounding Clay are more interesting than and just as fantastic as anything that can be made up about the man. Even to this day, guests will visit White Hall simply because they have either read or heard Townsend’s speech and will want to know more about Clay. When looking back over the influence this oration has had regarding its ability to capture the public’s interest, respect and gratitude should go to William H. Townsend for igniting the fire, so to speak, about this historical figure. However, it is the opinion of the authors that perhaps Townsend shouldn’t have tried to gild a lily that was already pretty brilliant to begin with.

Photograph of Warfield Bennett and William H. Townsend standing in front of White Hall, circa early 1950s. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Townsend’s speech was one listened to often by an attorney named Louie B. Nunn. His daughter, Jennie Lou Nunn Penn, recalled her father reclining in the family’s library at their home in Glasgow, Kentucky, listening to a recording of “The Lion of White Hall.” Years later, when Mr. Nunn was elected governor of Kentucky, he and his wife drove to Madison County to find Clay’s mansion. Penn stated, “I must say that although Daddy had to talk Mother into going with him, it was Mother who came back so excited and determined not to let Kentucky lose this piece of its history.”340

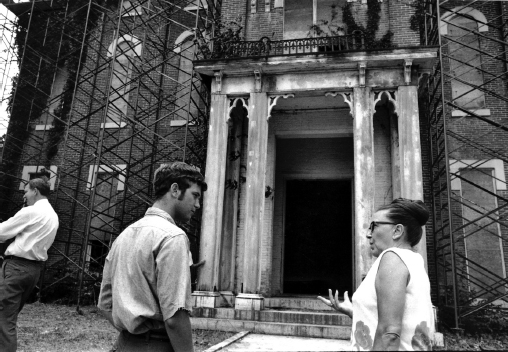

Through the very public effort of the Richmond Garden Club, Governor Edward Breathitt was made aware of the historic structure. Interestingly, a report prepared by Thomas R. Martinson of the Kentucky Heritage Commission dated September 3, 1967, lists White Hall as being the property of the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Mention is made in this account of the Kentucky Department of Parks surrounding White Hall with a chain link fence and boarding up all of the openings.341 Breathitt did secure the funds so that the Historic American Building Survey could record the mansion in August 1967.342 In addition, the Kentucky Department of Parks had already worked on repairing the leaky roof so that further damage would not take place to the interior.343 Clearly, progress was already underway for White Hall to become a state-owned site under Breathitt’s administration. However, although it was this elected official who initially set up an arrangement with the Bennett family to purchase a portion of Clay’s original estate, ultimately it was Governor Louie B. Nunn who signed the deed.

On July 5, 1968, for the sum of $18,375, 13.64 acres of land were transferred from Warfield C. Bennett; Warfield’s wife, Ann C. Bennett; and Warfield’s sister, Esther Bennett, to the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Along with the transfer of land, it was stipulated that the State of Kentucky would create an entrance to White Hall from the old Fox Town Road and provide fencing on either side of the road from the farmland it would go through. Although the Clay Family Cemetery was not included within the 13.6 acres purchased, the Commonwealth was also required to fence in the burial ground, restore the gravestones within the cemetery and be in charge of the upkeep of that area.344

Once the land and home became the property of the state, a massive fence replaced the chain link one in order to keep trespassers away. Guards were posted by day when no workers were present, and night watchmen patrolled the property at night. Governor Nunn put the restoration and decorating efforts into the capable hands of his wife, Mrs. Beula Nunn.

The structure of the mansion was sound, and aside from installing a new roof, repairing the collapsing wall on the west side of the warming kitchen and repointing mortar in the brickwork, no major work was needed.

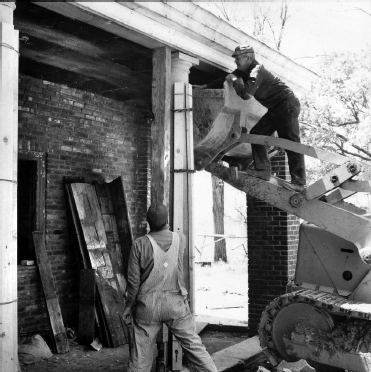

Photograph of workers restoring the columns on the back porch of White Hall. Notice the dirt porch area. This would later be filled in with hexagonal-shaped bricks original to the property. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Photograph of the grand staircase in 2012. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

Much of the woodwork in the mansion, particularly on the first floor, was still intact and showed off the natural beauty. However, for some reason not clearly known to the authors, all the woodwork was painted in the house. Perhaps, given the time, it was felt that painted wood was more attractive, and aesthetics took precedence over authenticity. Another reason could have been that the restorers felt that the woodwork should match, and it did not. To give uniformity, perhaps, it was then decided to paint the wood. The original main staircase banister, newel post and railings had been carted off or burned, and a replica based on photographic evidence was rebuilt. The spindles and decorative touches were painted a cream color, although pictures from before the staircase was destroyed clearly show the natural wood.

The original fireplace in the parlor of Clermont, which later became the dining room, had marble around the opening, and there was a “wedge-shaped keystone centered on the lintel.”345 This alone was beautiful and would have been impressive. However, a Federal-style mantel was brought in and made to fit over the opening.

Photograph of the dining room, circa late 1960s. Work is underway for restoration, as evidenced by the sawhorse and wood boards. Notice the original mantel, which would later be covered by another mantel. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Amazingly, the majority of the flooring (made up of a mixture of yellow poplar and pine) in the mansion is still original today. The only floors to not have survived (both collapsed before restoration could start) were an upstairs bedroom floor and the flooring to the 1810 warming kitchen. These were replaced with old wood and brick, respectively.

Restorers followed the Clay family’s original decorating color scheme by painting all of the mansion walls a bright creamy white color. In a second-floor bedroom, Cassius had slammed the original metal plates to his Memoirs against the wall and had written beside the imprints his intention of publishing another version of his work. According to one account, Clay’s handwriting was “amazingly clear and legible.”346 There was the intention of framing this area off so that guests would be able to view it on tour. However, the painters got to it before the framers did.347 Thus a window into the history of Cassius and his house was lost. The Clay family had also originally wallpapered a number of the rooms in the house, and this was taken into consideration, although none of the paper was preserved. What walls weren’t left the white shade were papered in historic reproduction wallpaper.

Looters long ago had ripped away the original metal to the bathtub. The state replaced it with a copper lining.348 Likewise, the original woodwork to the wastewater disposal room had been torn away, either by looters or by state restorers. A porcelain sink was put in the place of the original wooden structure, and thus began the onset of forty years of misperception and misinterpretation on the usage of the room. The toilet room was cleaned out, and an earth closet was placed where the original flushing toilet would have been. This was an inaccurate representation of what the Clay family would have had, but it was correct to the time period in which the Clay family lived.

Photograph of the bathtub with original zinc lining, circa 1950s. Notice the structure juts out from the wall to make room for the piping. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Photograph of the original pipes leading down from the water storage tank to the bathtub, circa 1950s. Notice the shower above the bathtub. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Photograph of the copper-lined bathtub in 2012. Notice the structure is fitted flush against the wall. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

The water storage tank on the third floor had the lining refurbished, three drains were added in to show where the water would have drained out349 and glass plates were installed over top of the cistern so that guests could view inside the reservoir. A railing was added around the storage tank for safety.

The basement proved to be an area that probably could have used a HazMat team. Decades of trash had filled the area to the brim. The original furnace was mistaken for garbage and carted out with the massive amounts of trash from the basement.350 The original ceilings were lowered somewhat with the installation of electrical lights, and the original dirt floor was covered with brick.

Master carpenter Floyd Nuckols oversaw the structural restoration. Nuckols had great appreciation for the work his predecessors Lewinski and McMurtry had accomplished in their construction of the mansion, and he stated that “restoring White Hall was like reassembling a fine piece of art.”351

A restored home is impressive to behold, but an empty mansion is not quite as striking as a furnished one. Once the mansion was complete, it then became Mrs. Beula Nunn’s mission to fill the home with historic pieces. She hired a team to track down Clay family descendants who may have inherited a portion of the Clay estate. She also had these individuals study the original 1903 auction list and search for the descendants of the purchasers. Amazingly, contacts were made, and individuals were generous enough to donate artifacts to the state.352 Mrs. Nunn was so successful that she was able to furnish White Hall almost entirely from donations and from her findings in Kentucky State’s surplus storerooms. According to one account, the only purchase of furniture made by Nunn was a bedroom suite of rosewood, which Beula stated “was early Kentucky and there was no other way I could talk the woman out of it.”353

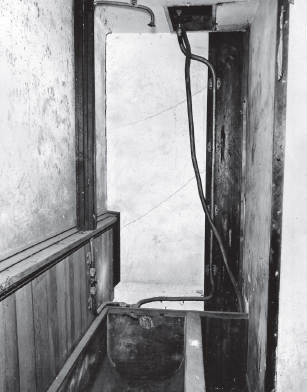

Photograph of the wastewater disposal room, circa 1954. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Photograph of the wastewater disposal room, 2012. The original wooden structure was replaced by a porcelain sink. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

Photograph of the toilet room, circa 1950s. Notice the original piping and wooden base for the toilet. The wooden piece with the circular cutout is the top of the structure from the wastewater disposal room. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Photograph of the toilet room in 2012, shown with an earth closet. Notice that the piping that originally was exposed is now covered by wall. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

Photograph of the water storage tank on the third floor, circa 1950s. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Photograph of the water storage tank in 2012. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

Photograph of the basement, circa 1965. Notice the finished ceilings. Courtesy of James M. Cox.

Photograph of the basement in 2012. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

Mrs. Nunn had knowledge of and an eye for interesting pieces, and if those pieces had Clay connections, so much the better. If an owner did not readily donate or sell the coveted piece, then she had other ways of acquiring the artifact. Being the state’s first lady didn’t hurt. One such item that Mrs. Nunn ran across and became determined to obtain by any means necessary was a bust of Cassius M. Clay. Joel Tanner Hart was born in Winchester, Kentucky, but was classically trained in the art of sculpture. His first subject was Cassius.354 After Cassius’s death, Clay descendants donated the bust to the University of Kentucky (UK), where it resided in Special Collections and Archives. When Nunn was informed of the location of said bust, she just had to have it. She wasted no time in getting assistance from another Clay, Albert Clay (not known if he was actually related to the Clays discussed in this book), who at the time was the vice-chairman of the UK board of trustees, and convinced the man to open up some doors for her on campus. Nunn planned a heist that would have put a professional jewel thief to shame.

Photograph of the elusive bust of Cassius M. Clay sculpted by Joel T. Hart. Notice that the docent is very proud that the artwork is in the mansion. Courtesy of James M. Cox.

Nunn executed her plan with success, and she proudly displayed the bust in White Hall. The University of Kentucky was informed of the location of its absent artwork and allowed the bust to remain at the historic site until the Nunns left public office as the first family. The sculpture was then transported back to the university, never to again see the light of day outside Special Collections’ walls. Years later, in an effort to showcase the piece at a Clay family reunion, the curator made multiple attempts to have a loan made between the two institutions. However, UK was not willing to part with the bust for even a short period of time. Perhaps the university felt that possession is indeed nine-tenths of the law.

Despite the exodus of that particular artifact, other items with Clay connections made their way back to the old homestead and have resided there ever since. Some artifacts were donated during the restoration of the mansion; others were given years later. White Hall has numerous antique items that are warranted by their beauty and history alone; however, staff members are especially proud of a number of items that have clear Clay family connections. These pieces are worthy of merit not only on their own but also in that they help strengthen the Clay family’s legacy in a tangible way.

Probably one of the earliest family pieces on display is an American eagle pommel sword, circa 1808, believed to have been used by General Green Clay when he served in the War of 1812. As briefly discussed in the first chapter, General Green Clay’s military career was very imposing. Clay served in the Revolutionary War. Arguably, his most impressive service was as a brigadier general in the War of 1812. Green Clay was one of numerous Kentuckians who united around his country’s flag, and in May 1813, Green led three thousand volunteers in the relief of Fort Meigs in northern Ohio.

General Harrison was in command at the time and was surrounded by British and Indian armies. Green cut his way through the enemy lines, and the British troops were forced to give way to him and his militia. General Harrison left General Clay in command of Fort Meigs. Later in the autumn of that same year, the fort was invaded a second time, by General Proctor and 1,500 British troops, as well as Tecumseh and 5,000 Native Americans. However, these opposing troops were unsuccessful and, in the end, were forced to retreat. In an inventory of General Green Clay’s possessions from Fort Meigs, there is a sword listed in with his personal belongings. This is believed to be the sword in White Hall’s collection.

The sword had been handed down from generation to generation of Clay family members and eventually was put up for auction. It was then purchased by a private collector. The collector maintained the sword for several years. In 2007, the Kentucky State Park Foundation purchased the sword for display at White Hall.

Another fine piece of weaponry that belonged to a Clay is Cassius M. Clay’s cannon. Since Cassius’s time, stories have abounded regarding Clay and his infamous pair of cannons. Interestingly, in all of the stories that the authors have been able to clearly document, the cannons were never actually fired but rather were simply used for intimidation purposes. Unfortunately, the White Hall staff was previously only able to recount (and debunk) stories of the artillery and their usage with just a photograph to prove of their existence.

This all changed in 2003 when one of the weapons was generously donated back to the site by a Clay family descendant. A reference made in a newspaper article stated that the other cannon had been donated to the Tennessee Historical Society,355 which prompted the curator to call the organization and inquire about said piece. Sadly, the spokesman for the society claimed to not know anything about the artifact (probably as he stroked the big gun on his office desk a la evil genius Ernst Stavro Blofeld, stroking his white cat in a James Bond film).

Photograph of Cassius M. Clay’s cannon. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

It’s not all about the boy toys, though. White Hall has many fine pieces of furniture; two artifacts that were very personal to Cassius M. Clay are his gout stool and his Wooton desk. As previously mentioned, Cassius developed gout, a type of arthritis that affects the joints, most of the time in an individual’s legs and feet, which makes walking very difficult and painful for the afflicted. The condition is caused by uric acid, a waste product made by the body. Normally, uric acid is flushed out of the body through the kidneys and urine. When an individual has too much of this waste product, the acid produces crystals that typically become deposited in the joints. Such deposits cause inflammation, resulting in swelling, tenderness and pain in the affected area.

Clay’s gout stool is designed so that it can be moved in two different directions in height and angle, hopefully relieving the leg and foot pain of the afflicted limb. A former curator once commented that this was a favorite piece of furniture of hers because “[t] o me this is a very personal piece of furniture that is indicative of his failing health and the human weakness endured by Cassius.”356 Clay was in good company with other historic individuals afflicted with gout, including Samuel Johnson, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and John Milton, who died as a result of complications from the condition. Milton reportedly told a friend that if he did not have gout pain, his blindness would have been bearable.357 It may have seemed that Cassius was invincible, but in reality, he was human just like the rest of us.

Whereas the gout stool is a small, unassuming piece of furniture, the Wooton desk inspires in guests awe and an obsessive-compulsive desire to organize their home or office once they leave White Hall. For those who liked orderliness, the Wooton patent office secretary desk was ideal. Originally created by William S. Wooton in 1874 in Indianapolis, Indiana, this desk was produced at a time when one man could manage a business with one large desk in which all of his records could be filed. The desk’s heyday was in the 1870s, when the industrial revolution caused an increase in business activity, and more desk and file capacity was required. Sadly, by the 1890s, the Wooton had become outdated, as typewriters and duplicating machines made smaller desks more popular. The Wooton desk today stands as a testament of form following function. The desk was immensely useful in its prime and still today stands as a beautiful piece of American history. Wooton patent cabinet office secretary desks came in four different grades: ordinary, standard, extra grade and superior grade. White Hall has a standard grade desk, which Cassius M. Clay originally owned and then passed on to his son Brutus Clay. Perhaps he even used it when he wrote his Memoirs.

Photograph of Cassius M. Clay’s Wooton patent office secretary desk. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

In his seventies, Cassius M. Clay chose to pen his Memoirs in an effort to memorialize his actions regarding antislavery and politics. The Life Memoirs, Writings and Speeches of Cassius M. Clay, vol. 1, was a six-hundred-page memoir that spanned Clay’s life up to the mid-1880s. In addition to covering the politics that Clay was involved with, topics within the book are varied and range from Clay’s favorite authors to his defense of an African American foreman against the Ku Klux Klan. As the name implies, the work also contains a great deal of Clay’s writings and speeches, as well as various letters.

Clay’s Memoirs, when originally published, were sold by subscription only. Buyers could choose from four different styles ranging in price from five to ten dollars. Although the subscription was to be for two volumes, only one was ever published.358 Few original copies of the Memoirs still exist today. In 1968, a reprinting of the Memoirs that included a reference index was produced in Berea, Kentucky, and coincided with the opening of White Hall State Historic Site. In addition, Negro University Press did a reprinting in 1969, though without an index. Today, reprinted copies can be purchased online; one can even search the inside of the book via Google Books.

In speaking of his Memoirs, Cassius stated, “Henry Wilson seems to think that the emancipation proclamations are the great events, not only of the war, but of the age. They are. But he also seems to be quite in the mist as to the causes and movements in that regard. To show my connection with these great events, and to throw light on their causes and effects, is one of the most potent motives for my writing these Memoirs.”359 Cassius M. Clay was a man who aspired to greatness, certainly with his ideals concerning freedom, and it is regrettable that he is often overlooked in the pages of history. Oftentimes, the legends surrounding the man take precedence over the facts. It is therefore heartening that a work exists to prove that Clay was, in his own words, “Quorum pars fui” (“Of them I was a part”).

There are sections of the Memoirs in which Cassius does not speak well of his first wife, Mary Jane. Because of this, his children tried their best to eradicate the publication but were unsuccessful. Few original copies exist today, but there are still a few floating around, and occasionally the tides of chance wash a copy back to the shore of White Hall.

While some artifacts, such as the Memoirs, are able to tell all, others give silent testimony. The expression “If these walls could talk…” has been used often. Certainly, such could be said about White Hall. This expression can also be used when referring to Mary Jane Warfield Clay’s royal Russian presentation dress. When Cassius M. Clay was appointed minister to Russia in 1861, Mary Jane Warfield Clay and five of their children traveled to Russia with him. It was customary at the time for the foreign ministers and their spouses to be presented to the imperial Russian court. Attire for such an occasion must be perfect. In an October 28, 1862 letter addressed to her sister, Julia, Mary Jane discussed her search for the ideal dress: “I went out this week in search of a court dress…A ball dress is the dress…I selected an [sic] gold silk covered with white velvet figures a goods somewhat resembling my old rose colored velvet of Grandmamma Barr’s…I will hand it down to my grandchildren as Grandmamma’s descended to me…I bought a headdress of feathers and gold cords and tassels to wear with it.”360

Just as Mary Jane had envisioned, the lovely gold presentation gown went on to be worn by her descendants. Mary Jane’s eldest daughter, Mary Barr Clay Herrick, visited her uncle Brutus in Washington in 1864 and, while there, wrote back to her mother, “Last night we went to Mrs. Lincoln and Pres. Lincoln’s. The house was crowded and all kinds of dressings. I wore your yellow silk…and had many compliments paid.”361 Nearly twenty years later, Mary Jane’s youngest daughter, Anne Clay Crenshaw, had a studio portrait made of herself in the dress refashioned in a contemporary style. Mrs. H. Hersee Bullock Jr. (aka Mary Barr Clay Bullock), a great-granddaughter of Mary Jane’s, wore the dress, redesigned a third time, at a “Lincoln tea” given by the Historic Memorials Society in the late 1920s or early 1930s.362 Later, at an unknown point, the dress was altered a fourth and final time, and this is how the dress appears today. This dress witnessed the royal Russian court in its prime, it encountered what could be arguably called the greatest president of the United States and it was passed down through at least four generations of Clay family women. The dress eventually was donated to the J.T. Doris exhibit at Eastern Kentucky University and is on loan to and currently on display at White Hall State Historic Site.

Photograph of Mary Jane Warfield in her Russian presentation dress, circa 1862. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

These are, of course, only a few examples of all the amazing items that came to be on display in the mansion. Furnishings and decorative pieces arrived from descendants, as well as local people who had an interest in helping furnish the mansion. In addition, items were purchased from antique businesses, as well as from collections already owned by the State of Kentucky. Even bartering took place, as Beula Nunn traded with a local house museum, giving it a painting in exchange for Clay’s dueling pistols.363

The mansion was not the only building to be restored. There were seven additional original structures still standing when the state took control of the property. The icehouse, located behind the mansion, had the trash cleaned out of the deep circular structure and a new roof built over top of it. The henhouse had new siding and a new roof built on, and it retained its original white color. The old mule barn located in front of the mansion was kept in the same location but was reoriented at a ninety-degree angle. The walls and roof were reconstructed and doors added. A brick sidewalk was added around the building. From the opening of White Hall in 1971 to 2009, this building was used as a gift shop for the park. The gristmill beside the mule barn also sported a new roof and reinforced sides. The interior of this building was gutted so that restrooms could be installed for the public. A wooden and stone building located beside the gristmill, which could have been originally used as a tack shop or storage site for lumber or grain, was cleaned up and repaired as well. Two other original buildings, the stone kitchen/loom house and the smokehouse, were restored at a later time.

Trees and other plantings were incorporated into a landscape design for the park. The Richmond Garden Club continued supporting the mansion by installing a flower garden into a circular brick-lined flowerbed that faced the conservatory.

To make access easier from the interstate, the highway department paved a road from US 25 to the mansion.364 A parking lot was also paved on the park, as well as a circular drive leading up to the great house.365

When Louie B. Nunn became governor, his wife was asked what she would do in Frankfort. “Just mend the roof on the Capitol,”366 Beula Nunn replied. Mrs. Nunn did that and additionally restored the State Reception Room in that building and redesigned the Governor’s Mansion. The Nunns helped to establish the Kentucky Mansions Preservation Foundation.367 This would serve as a repository for the Governor’s Mansion, White Hall and, later, the Mary Todd Lincoln House in Lexington, Kentucky—she led a campaign for the acquisition and restoration of the latter site.368 It is the authors’ biased belief, however, that her greatest accomplishment was the enormous amount of enthusiasm and arduous labor of love that she put into White Hall. In speaking of her work on White Hall, Circuit Judge James Chenault once said, “She has spent countless hours here. If there was a spot on the floor, she would get down on her hands and knees and fix it herself. She even moved a trailer to the grounds and often stayed overnight. The governor lost a wife but White Hall gained a caretaker.”369 Certainly this great lady had drive and ambition, and she accomplished much in a mere four years.

Photograph of First Lady Beula Nunn and William Bennett in front of White Hall, circa 1964. William Bennett is a great-great-grandson of Cassius M. Clay. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Originally, the plan was for the restoration to take place over a period of six years.370 However, as the Nunns’ administration came to a close, the work was sped up so that the opening could still be held within their reign. Although the state tried to keep costs down by using inmates from the LaGrange and Eddyville Prisons to do a large portion of the work—such as duplicating woodwork, doors and shutters in the mansion and refinishing furniture,371 the restoration ended up costing the state $124,000. Of this amount, $24,000 came from the Parks Department, while the lion’s share (pun intended) of $100,000 was ponied up by capital funds.372 The end result of the park and mansion, however, is priceless.

Through years of hard work, the mansion was once again beautifully furnished and was indeed a showplace. If you build it (and repair, wallpaper, paint and furnish it), he (and she and they) will come. Now let’s take a look at White Hall and how the site has changed over the last forty years or more of public service.