PART V

WHITE HALL STATE HISTORIC SITE

Greater than the Glory of the Former House

The glory of this present house will be greater than the glory of the former house, says the Lord Almighty. And in this place I will grant peace, declares the Lord Almighty.

–Haggai 2:9, New International Version

September 16, 1971, was a perfect late summer day. Governor and First Lady Nunn declared that date “Madison County Day” and invited all of the residents of that region to attend a 2:00 p.m. ceremony that would mark the official opening of White Hall, a Kentucky State Shrine.373 The inaugural celebration was met with a very enthusiastic crowd. Photographs from the day show a multitude of people grouped together on the park grounds or crowded into the rooms of the mansion.

Circuit Judge James S. Chenault served as master of ceremonies on that momentous day and welcomed the guests under a grove of trees. Many individuals and organizations were honored, including the Richmond Garden Club, the Madison County Historical Society, First Lady Beula Nunn (who was considered a guest of honor on that day) and various Kentucky State employees, to name a few.374 Governor Louie B. Nunn addressed the crowd of some 1,500 attendees. In reference to the extensive work that had taken place at White Hall, Nunn stated, “By repairing, by restoring White Hall to its original splendor, our goal is to resurrect more than just a home. Our hope is that we shall have helped to restore the magnificent spirit born here, a spirit which never really died but still touches the lives of free men everywhere.”375 Governor Nunn also spoke about Cassius M. Clay, claiming, “He lived his years in such a manner that the course of history was forever altered. His shadow extended beyond his own time into our time and by preserving this, his home, we will insure that his shadow will extend into the future.”376

Photograph of opening day, September 16, 1971. Guests gather in the brick-lined flower garden that had been restored and landscaped by the Richmond Garden Club. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

At its opening, the park had the slightly exalted title of White Hall State Shrine. This name continued on until the mid-1980s,377 when White Hall State Historic Site became the moniker, although the locals still insist it’s “The Shrine.”

Though the park would open with a restored mansion, grounds and several outbuildings, two other structures would be repaired at a later date. The smokehouse was toured on opening day as a skeletal building, with only the four corners and roof in place; the walls and foundational portions of the structure were later added back.

The stone kitchen and loom house slowly deteriorated for two more decades before restoration began on the building. The building’s history was heavily researched, and very few changes to the original structure were made. The outside wall stonework was removed but numbered, so that it was placed back in its original location. New flooring and wooden supports over the massive fireplaces were installed; however, the support beams in both buildings and the wooden walls in the loom house remain the original. The end result was a structure that Green Clay would have recognized as his own had he returned from the grave. This building was opened to the public for the first time in 1995, complete with an interpreter who would bake biscuits on the hearth just like slaves would have been done in the late 1700s, when the building was first erected. This interpretation continued for a little more than a decade when, due to lack of staffing and funds, the building became a self-interpreted part of the park.

Photograph of opening day, September 16, 1971. A beaming docent shows the master bedroom to a crowd of young guests. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks.

Photograph of opening day, September 16, 1971. A large crowd gathers under the Kentucky coffee bean tree to listen to speakers. The tree was considered the largest in Kentucky before it succumbed to the elements and was removed in 1993. Courtesy of James M. Cox.

Photograph of the smokehouse and chicken house before restoration, circa 1965. On opening day in 1971, these buildings would appear very similar to this, but they were later restored. Courtesy of James M. Cox.

Photograph of the smokehouse and chicken house in 2012. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

Photograph of the stone kitchen and loom house, circa 1965. Courtesy of James M. Cox.

Photograph of the stone kitchen and loom house in 2012. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

Research is still being conducted concerning the usage and placement of other original buildings on the property. Whenever a heavy drought occurs, the outlines of the old buildings and the original carriage path slowly start surfacing on the grounds. It is like seeing the ghosts of these former buildings appear. In the summer of 2012, archaeological work began on the park to discover some of the secrets that the terrain holds. Who knows what fascinating information will be discovered as the work progresses.

In 1998 and 1999, the mansion received a modern makeover in the form of an updated heating system with an air-conditioning addition. For those employees and guests who endured the mansion on a hot summer’s day, this latest innovation was most appreciated, as temperatures could reach over one hundred degrees on the top floor in the summer months. The heat certainly gave guests a more authentic experience for how the Clay family would have lived. The air conditioning was not just for the comfort of guests and staff but was also employed to control the changing humidity and better preserve the priceless artifacts contained within the mansion. In a nod to the original heating system installed in Cassius and Mary Jane’s time, the workmen used the innovative ductwork from the original heating system to run the wiring through the mansion for the modern heating. Reproduction armoires were installed in various rooms of the mansion to tuck the massive HVAC units inside. In addition the mansion also received freshly painted walls in shades of cream, green and burgundy and a new copper roof. Historic reproduction carpeting was added soon after.

Photograph of the formal reception hall in 2012. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

Photograph of the drawing room in 2012. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

Photograph of the library in 2012. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

Photograph of Sarah’s room in 2012. Courtesy of Kentucky Department of Parks and Liz Thomas Photography.

White Hall has received many accolades over the years. On March 11, 1971, the house was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.378 Forty years later, on April 12, 2011, in recognition of Cassius M. Clay’s newspaper the True American, the Society of Professional Journalists honored White Hall with a Historic Site in Journalism Award, making the mansion the ninety-ninth site in the United States with that distinction.379

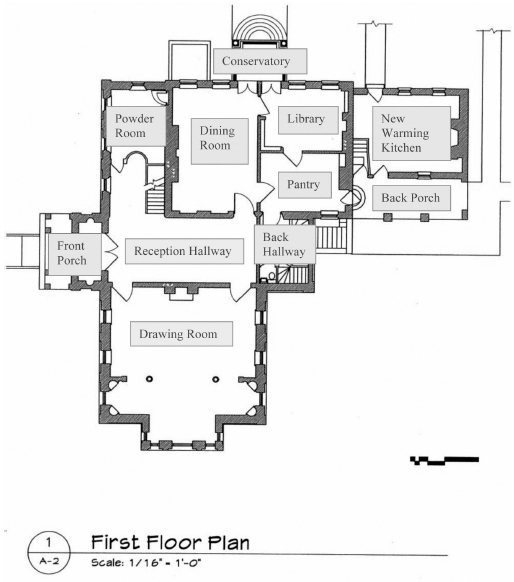

The mansion is about ten thousand square feet. Guests at White Hall can be treated to a lengthy tour in which nearly every room and floor in the mansion are shown. It is a source of pride with the staff that the majority of the mansion is exhibited to guests. Only a few areas are inaccessible, due to the need for storage space. Unfortunately, because of the many floors and levels, the home is not handicap-accessible, as there are 129 steps in and around the home that the guest would have to maneuver.

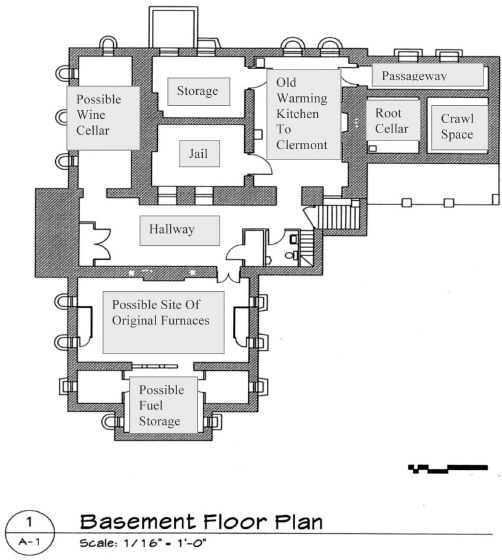

Since Cassius’s time, the mansion has boasted about forty rooms. (Some say forty-two380 and others say forty-four.) For those skeptical of the large number of rooms, one must consider that the large, expansive hallways are considered rooms, as are all of the closets (of which there are seventeen if you include the bathroom closets). In addition, the rooms located in the basement are also included in the number. For clarification purposes in the following list, when referring to the usage of the rooms, “Clermont” is in parenthesis after usage that would have taken place when the house was first completed in 1799 running up to the beginning of the new addition in the mid-1860s. “White Hall” is used to describe room usage from 1864 to 1903, and “modern” is used in reference to the usage and naming of the rooms after the home became a historic site. Although the names of the Clay children have been given to the rooms, it is not known who actually slept in the space.

• powder room (White Hall)

• first-floor hallway (White Hall)

• drawing room (White Hall)

• parlor (Clermont); dining room (White Hall)

• parlor (Clermont); library (White Hall)

• dining room (Clermont); pantry (White Hall)

• second-floor hallway (White Hall)

• bedroom (White Hall); Laura’s room (modern)

• Laura’s first closet (White Hall)

• Laura’s second closet (White Hall)

• bedroom (White Hall); Sarah’s room (modern)

• Sarah’s first closet (White Hall)

• Sarah’s second closet (White Hall)

• toilet closet (White Hall)

• wastewater disposal closet (White Hall)

• tub closet (White Hall)

• Green Clay’s room and additional bedroom (Clermont); Cassius’s room (White Hall)

• master bedroom (modern)

• master bedroom first closet (White Hall)

• master bedroom second closet (White Hall)

• master bedroom third closet (White Hall)

• additional room (White Hall); tower room (modern)

• bedroom (Clermont/White Hall); children’s room (modern)

• bedroom (Clermont/White Hall); nursery (modern)

• attic space (Clermont); bedroom (White Hall); Anne’s room (modern)

• attic space (Clermont); bedroom (White Hall); archives (modern)

• third-floor hallway (White Hall)

• bedroom (White Hall); Mary Barr’s room (modern)

• Mary Barr’s first closet (White Hall)

• Mary Barr’s second closet (White Hall)

• bedroom (White Hall); Brutus’s room (modern)

• Brutus’s first closet (White Hall)

• Brutus’s second closet (White Hall)

• bedroom (White Hall); history room (modern)

• history room first closet (White Hall)

• history room second closet (White Hall)

• basement hallway (White Hall)

• old warming kitchen (Clermont)

• old warming kitchen storage room (Clermont)

• jail (Clermont)

• first back fuel and heater storage room (White Hall)

• second back fuel and heater storage room (White Hall)

• possibly a wine cellar (White Hall); break room (modern)

• possibly a cook’s residence office (Clermont/White Hall); business office (modern)

• new warming kitchen (Clermont); cooking kitchen (White Hall); event space (modern)

In addition, guests are also told that the mansion includes three main floors, and because of the differences in ceiling heights on the first floor, the house contains a total of nine levels, as follows:

• first floor

• second floor, new section

• second floor, old section

• tower room

• attic space/Anne’s room/archives

• third floor

• basement

• new warming kitchen

• office

Floor plan of White Hall’s basement. Text inserted by the authors. Courtesy of Gregory Fitzsimons.

While viewing the mansion, guests are treated to an exemplary tour. The staff continuously conducts research in order to remain up to date on the history of the site and the Clay family. In addition, the docents lead a tour that is more like a friend accompanying the guest through the home rather than a stiff and structured presentation. One former guide who trained new employees at White Hall relayed to the fresh docents, “First and foremost, this is your home. You’re going to be here for eight hours a day, five days a week. This is your second home, so treat your guests like they’re coming into your house and you’re telling them about your family, because you are going to adopt the Clays and they are going to be your family.”381

Floor plan of White Hall’s first floor. Text inserted by the authors. Courtesy of Gregory Fitzsimons.

In addition to guided tours, the park and mansion have played host to many events throughout the years. In the first three decades of operation, historic reenactments were common on the grounds. The park has also welcomed car, antique and flower shows, as well as cultural events such as symphony orchestras and theatrical events. The mansion has been decked for the holidays off and on throughout the years and has been the setting for ghostly appearances in the form of guided ghost tours and the annual Ghost Walk, an excellent theatrical production based on the Clay family’s life. White Hall has also welcomed Green and Cassius’s descendants and relatives back to their ancestral home by hosting a number of Clay family reunions. To successfully present these programs along with the normal guided tours takes a dedicated group of employees.

Floor plan of White Hall’s second floor. Text inserted by the authors. Courtesy of Gregory Fitzsimons.

Staffing has changed drastically over the four decades the site has been open to the populace. Changes in tour operations, the addition and subtraction of areas open to the public and the economy have all played important factors. Permanent full-time positions included a park manager who at the beginning was in charge of only White Hall up to a time when that post handled the operations of both White Hall and neighboring Fort Boonesborough Kentucky State Park in the mid-1970s, when the fort opened. The manager position had then returned to just maintaining control over just White Hall by the late 1980s, lasting to early 1990s. A secretary, later referred to as a business office manager, was employed until the position was eliminated in 2004. Maintenance has fluctuated over the years—at one point having three positions to maintain the numerous acres and problem-prone house; in recent years there has only been one person to deal with the upkeep. From the beginning, a staff member has always been employed as a housekeeper of the massive home. In the mid-1990s, the position was transitioned to a curatorial type of role.

Floor plan of White Hall’s third floor. Text inserted by the authors. Courtesy of Gregory Fitzsimons.

In terms of seasonal staff, upon opening in 1971, there were at least a dozen docents on staff, as well as a person employed in the gift shop.382 This continued on into the 1980s. The large number enabled the interpreters to take a guest in to the mansion for a tour whenever they happened to arrive on the park.383 By the mid-1990s, there was still one employee for the gift shop; however, the number of guides had been reduced to five. Set tour times were scheduled for guests, and so a smaller number of docents were needed. The stone kitchen and loom house had been restored and were opened to the public in 1995; therefore, a stone kitchen interpreter was also employed. This staffing model continued on until 2010 when, due to budgetary issues, the gift shop was closed down and the gift shop supervisor position eliminated. The stone kitchen and loom house, although still open for viewing by the public, was no longer staffed on a regular basis, and the tour guide staff was cut down to two interim positions. In spite of the increasingly reduced staff, guests can still expect to be greeted and given a stellar tour. The welcoming party is still there, just smaller.

As with any business, some staff members work at a site for a brief period, while others remain employed for years. Whether the time is short or long, many former employees reflect with fondness of their time at the “Big House,” as White Hall is affectionately called. In 2011, to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of White Hall State Historic Site’s opening to the public, a former employee reunion was organized. Employees from all four decades of operation attended and spent the evening reminiscing. When asked of their impressions of White Hall and the history, glowing accolades were numerous. One docent enthused, “White Hall is incomparable!”384 Another stated, “It is such a special place; it stays with you forever.”385 Still another admitted, “It was more than a job; it was love.”386 One tour guide in particular, when asked to relate his best memory of White Hall, stated, “Too many. When I worked there it felt more like home than nearly anywhere I’ve ever been.”387 In contemplation of their legacy, don’t you think the Clay family would be pleased?

A visitor to the home before restoration once commented, “There certainly is a great deal of heritage connected with this house. There are secrets hidden in all the dark corners of this brick mansion. No one will ever be able to reconstruct Cassius Clay’s true story completely, but by just walking through his aged home, one comes to realize that many of his untold realities are dying as his house slowly crumbles away.”388

Through the long progression of time, disinterest and neglect, a great deal of what is known about Cassius M. Clay, his family and his home has been lost. However, since the restoration and opening of White Hall, continued research and perseverance has allowed more of this remarkable story to be uncovered. Truly, not a week goes by that the authors do not discover some new facet about the Clays that adds another piece of the puzzle back to make the picture more complete. In years to come, more information will be discovered that will add new perspectives to what is already known about this great family and their fascinating home, and as a result it will make this work seem dated.

It had been a wish in one of Cassius M. Clay’s wills that his home and land would be given to the government for “the finest natural park on earth.”389 It is the view of these authors that Clay would have approved of White Hall State Historic Site as it stands today. Guests are able to enjoy the beautiful mansion, outbuildings and grounds and imagine, for a time, what it might have been like to be a Clay.

Just as the potter is able to mold clay into numerous forms, so has White Hall State Historic Site gone through many transformations in its lifetime. The home originated with Green Clay as a single-family dwelling and became enlarged through Cassius Marcellus Clay and Mary Jane Warfield Clay as a political and personal showplace. The building went through what could be considered an “Odinsleep”390 during the tenant farmer years and then experienced renewal through its restoration. It continues on today as a home with a rich and fascinating history of which Kentucky can be proud.