There are over 4,000 species of mammal in the world, and almost one in four of them is a bat. In Britain there are fewer than 50 truly native ‘land’ mammals, and one in three of these is a bat. Two species are so common, widespread and easily seen that they must be our most readily observable native mammals. Few mammals live closer to humans than bats. Many species roost unnoticed in our homes, and some are now almost entirely dependent on built structures for their survival. Bats are unique among mammals in being capable of powered flight. They are also one of just two groups that have a sophisticated echolocation system (the other being the dolphins and their relatives). Few mammals are more accomplished hibernators. So, here is a group of animals that constitutes a major component of our mammalian fauna, has widespread and common members, lives close to humans, and is biologically unusual and fascinating.

Why then, until recently, have relatively few naturalists taken an interest in bats? Is it the antisocial hours they keep? Only the most dedicated naturalist works far into the night. But this cannot be the answer: most bats are active at dusk, and many of our earthbound mammals keep equally unsociable hours. Perhaps it is because we do not see them often enough – it is hard to get close to a bat. But it is hard to get a close look at most of our smaller mammals, whether nocturnal or diurnal, and all are more timid than bats. In fact, bats will continue to forage in the presence of large groups of noisy, torch-wielding naturalists, and you can sit and watch them for hours – this can be said of few other mammals. Is it because it is difficult to identify flying bats? It is true that a flying bat can rarely be identified to species, and typically only be put into a category with several others. But there are many species out there, some with a distinctive flight style, and, with the help of inexpensive bat detectors, some can be identified. Maybe it is because they are hard to study. I doubt this too, and I will argue later that the keen naturalist can learn more about bats through his or her own efforts than they can about almost any other mammal. It is therefore difficult to come up with a rational reason for the long neglect of bats. On the other hand, it is quite easy to explain their current popularity.

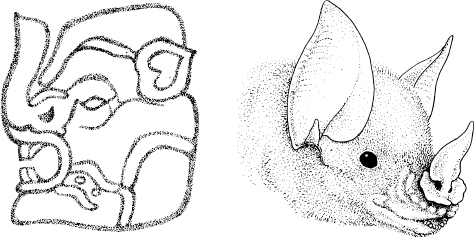

Knowledge and understanding may have been late in coming, but people have long been fascinated by bats. In western cultures this has been based largely on fear and superstition: Bram Stoker has a great deal to answer for! Before the publication of Dracula in 1897, bats were not linked with witches, vampires and the evil side of the supernatural in any significant way. In European traditions, vampires were everything but bats: horses, dogs, spiders, frogs, snakes, even sheep, to name but a few. In the same gypsy cultures bats were often seen as symbols of good luck. This did not protect them: various parts of bat were carried around as charms. In the rest of the world bat mythology is richer, and bats were as often seen as omens of good as of evil. India has one of the strongest vampire traditions, but bats are never mentioned. Only in the New World is there a tradition of bats as vampires, and this of course has a firm biological basis: only in South and Central America are real vampire bats found. In Mayan mythology, Zotz, the vampire bat god, lived in the underworld, through which humans passed as they died. Zotz shows a striking resemblance to the spear-nosed bats, a numerous and diverse family of neotropical bats (Phyllostomidae), of which the vampire is a member (Fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.1 Left: Zotz, the vampire bat god from a Mayan carving. Right: a typical phyllostomid, Phyllostomus hastatus.

To most cultures, the night is a time of mystery, fear and often death, and bats have inevitably been linked with these matters. To the ancient Greeks, bats were associated with Persephone, wife of Hades, ruler of the underworld. An Australian Aboriginal legend tells of how the first man and woman were warned not to disturb a large bat venerated by the spirits. Curiosity got the better of the woman, who frightened the bat from its perch in front of a cave. The bat was the guardian of death, which was able to escape from the cave, bringing mortality to humans. Another Aboriginal myth relates how a fight between the birds and the ‘animals’ caused the god Yhi to hide the light. The bat, who had been led astray by the treacherous owl, made amends by cutting the darkness in two with a boomerang. He gave light to the birds and animals and took the darkness for himself. The owl was never forgiven, and is to this day mobbed by the birds as he flies out at dusk. Myths in many cultures explain why bats fly at night, and why they appear to be neither bird nor mammal.

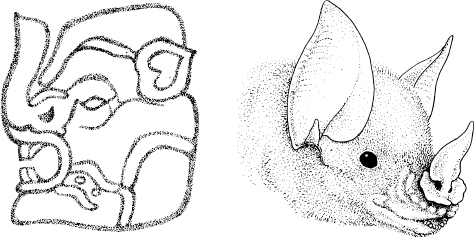

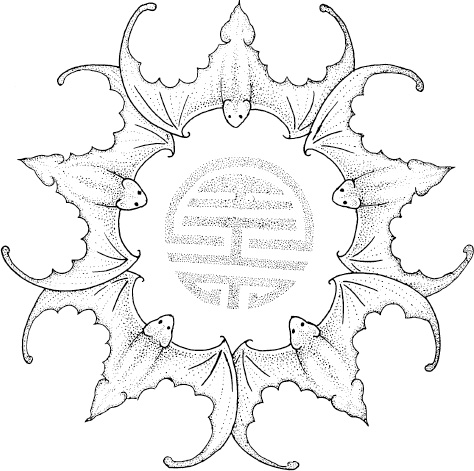

The traditional Chinese view of bats is the most positive. The bat is a symbol of good luck and happiness, and the common motive of five bats around a peach tree, the Wu-Fu (Fig. 1.2), represents the five great happinesses: health, wealth, good luck, long life and tranquillity.

Most of these myths are accepted for what they are, but some linger on as truths in the minds of many. It is still a widely held belief that bats are blind, that they get caught in your hair, or that vampire bats are everywhere, even in Britain. Thankfully, most people are now better informed.

Why have bats come out of their dark obscurity and into the light over the last two decades? Even now, initial curiosity is most often aroused by the myth and mystery that surround bats. However, more and more people are discovering that the truth about bats is far more interesting than the myth. The efforts of a dedicated group of professional and amateur biologists have played a major role in increasing public enlightenment. The Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 gave protection to all UK bats and their roosts, and was a catalyst to the growth of the county bat groups. Fauna and Flora International (the Fauna and Flora Preservation Society as it then was), the Mammal Society and the Vincent Wildlife Trust have played important roles in promoting bats, and continue to do so. The 1990s saw the formation of the Bat Conservation Trust out of the Bat Groups of Britain, to assist the work of the bat groups, and to carry out its own programme of activities.

Fig. 1.2 Wu-Fu, Chinese symbol of the five great happinesses: health, wealth, good luck, long life and tranquillity.

Advances in the technology used in both research and television bring newly discovered and fascinating aspects of bat biology right into people’s homes. A decade ago, bats made very rare appearances in natural history films. They are now a common feature, and several excellent programmes have been devoted to bats. New equipment accessible to the amateur as well as the professional brings us nearer to bats in the wild, increasing our understanding and hence our appreciation of these animals. Ultrasound or bat detectors enable us to listen to bats. Even the most primitive of detectors alerts us to the presence of bats and can help to identify species. Equipment costing no more than a good pair of binoculars can be used to make high quality recordings of echolocation and social calls, opening up new avenues of research and understanding to the amateur. For a similar price, adequate night vision equipment is also now available, and digital camcorders now have ‘nightshot’ facilities.

All these advances have helped bring bats into the light, and for many people the transition from ignorance to enthusiasm is swift and enduring. My own story illustrates this well. Although a professional biologist and a keen naturalist, I knew little about bats. Then, in the summer of 1984, I was taken to a Natterer’s bat roost. The trap was sprung instantly. As I examined the delicate but energetic animal in my hand it buzzed, struggled a little and then quietly dozed. I was hooked: I had to know more. As a researcher in biomechanics and animal locomotion, bat flight and echolocation had instant appeal, but I was equally enthralled by their enormous diversity and, to me, incomparable natural history. The more I read, the more I wanted to read. My interest in bats has retained an amateur flavour; a personal enthusiasm squeezed between my professional and personal lives, and part of both. What makes it worth the effort in an already hectic life is the quiet excitement of the field work and the shared enthusiasm.

Another factor is the constant awareness of just how little is known about our bats. Take the common pipistrelle. Over the last few years it has become apparent that it is two distinct species, with quite different lifestyles – the first new mammal species to be identified in the country for a very long time. Although we know where female pipistrelles set up their summer nursery roosts, we have little idea about where the males roost in summer. We have even less idea about where both sexes hibernate – our most common bats all but disappear in winter. The picture is similar for most species. Both amateur and professional naturalists have no shortage of questions to ask and to seek answers to.

The study of the natural history of bats is fulfilling in its own right, but there is a more practical side to it. There is good evidence, if often circumstantial, that many of our bat species are in decline. Action is needed if this decline is to be stopped. This action can take many forms, but fundamental to all our conservation efforts is the need for a deeper knowledge of the biology and natural history of our bats. A naturalist’s enthusiasm comes from an understanding of his or her subject. To infect others with this enthusiasm, this knowledge needs to be passed on. It is a tool for informing, inspiring and persuading. Good conservation relies on this knowledge. The best conservationists, at all amateur and professional levels, know their biology and are good natural historians. Conservation organisations have been enormously effective in making the public aware that bats need our help, and have increased the public understanding of bats. However, I believe that in this and other areas of conservation, awareness and support have often preceded knowledge. Too many people know too little about what they agree needs conserving. Many people may know all they want to know, but there are others eager to learn. The more that is known about our wildlife and environment, the better we can conserve what we still have, and the more our own lives are enriched and enjoyed.

My aim is to provide a readable overview of the natural history of our native bats. If you are not already a bat naturalist, I hope it will persuade you to get out and see and hear bats for yourself. As small, nocturnal and very mobile mammals go, bats are surprisingly accessible and wonderfully fascinating. I believe the first step in nature conservation, and the best, is to grip your audience with the fascination of nature itself. The need for conservation is then self-evident, without the need for heavy-handed preaching or a homocentric appraisal of why wildlife is important to us. I hope that this book goes a little way towards fulfilling this first step.