The birth of air mail . . . more than thirty years before the Wright brothers’ first flight.

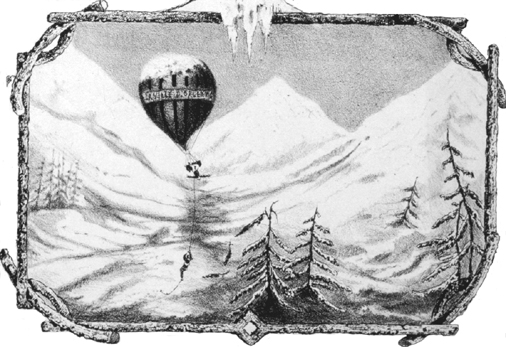

In 1870 the Prussian army had Paris under siege. The city was surrounded. For five months there was no way in or out. Except by air. In order to keep in touch with the rest of the world, Parisians turned their attentions skyward. Two of the city’s railroad stations were turned into balloon factories. Seamen were trained as balloonists. Over the duration of the siege, sixty-four hot-air balloons were produced and launched. Two were lost at sea, and six were captured by the Prussians. But the rest managed to carry more than two million dispatches to the outside world—nearly ten tons of mail.

Alas, the world’s first airmail service had one drawback: it went only one way.

They couldn’t use balloons to get messages back to Paris, because it is almost impossible to control where a balloon will go. To solve that problem, the balloons leaving the city carried hundreds of carrier pigeons. The birds were taken to various cities, loaded with messages for Paris, and then released. Letters were photographed, reduced in size, and printed on thin films that could hold up to twenty-five hundred messages each. A single pigeon could carry as many as a dozen strips of film with more than thirty thousand dispatches.

The pigeons, however, weren’t as reliable as the balloons. Only one in eight made it back. But they carried over a million messages back to the besieged Parisians.

Airmail: a wartime innovation that couldn’t wait for the airplane.

At Orléans Station in Paris, more than a hundred women worked to make the balloons. They treated the calico fabric with linseed oil, ironed it, cut the material to precise measurements, then sewed the pieces together by hand.

One balloon leaving the besieged city flew 875 miles and landed in a Norwegian forest.