Ever since nuclear weapons were first used at the end of World War II, there have been proposals to eliminate them. The world today is largely united on the merits of this goal but remains deeply divided over how to achieve it. Some commentators call for mass popular movements. Some urge the states with the largest nuclear arsenals to lead the way. Some have sought to redefine what “zero” means, saying that “virtual” arsenals or nondeployed weapons are an acceptable goal. Some insist on absolute preconditions. Some address disarmament as merely a “vision” or “ultimate goal.” A few seem to believe that achieving this goal will require nothing less than world government.

Now that “global nuclear disarmament” is finally receiving the attention it deserves, this is a good time to examine some of the recent proposals for achieving it, their antecedents, and some of the challenges that such efforts will need to address if they are to prove successful.

If Rip van Winkle had awoken on January 4, 2007, and read his Wall Street Journal, he could well have concluded that former U.S. secretaries of state George Shultz and Henry Kissinger, former secretary of defense William Perry, and former senator Sam Nunn (D-Ga.) had just invented a wonderful new idea: the vision of a world free of nuclear weapons.1

He would not have known that “disarmament” appeared twice in the UN Charter, which was adopted before the first nuclear test, and that the General Assembly had identified the goal of eliminating all nuclear weapons and other “weapons adaptable to mass destruction” in its first resolution, adopted in London on January 24, 1946. This was the same year that the U.S. government produced the Acheson-Lilienthal report and Baruch Plan, and the Soviet Union offered what came to be called the Gromyko Plan, all ostensibly aimed at achieving a nuclear weapon–free world.

He would not have known about the near miss in May 1955, when the nuclear powers came very close to agreement on a plan for nuclear disarmament in Geneva. Nor could he have known that the General Assembly put “general and complete disarmament [GCD] under effective international control”—aiming at the elimination of weapons of mass destruction and the limitation of conventional arms—on its agenda in 1959, where it has been ever since. He would not have known that President John Kennedy introduced his own detailed GCD proposal in the General Assembly on September 25, 1961, or that the United States and Soviet Union released that month the McCloy-Zorin statement of “agreed principles” for achieving GCD, a concept that would later be incorporated in a dozen multilateral treaties.

He would not have known about the conclusion of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1968, which addressed both nuclear disarmament and GCD. A decade later, the General Assembly would convene its first special session on disarmament and agree that although GCD was the world community’s “ultimate objective,” nuclear disarmament would be its top priority. He would not have known about the Reykjavik summit in 1986, when U.S. president Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev discussed the elimination of nuclear weapons and long-range ballistic missiles.

He would also not have been aware of the five treaties creating regional nuclear weapon–free zones that also address GCD, nor the hundreds of resolutions that the General Assembly had adopted over six decades for global nuclear disarmament. He would not have heard of the 1996 advisory opinion by the International Court of Justice, which held that the NPT parties had a duty not just to negotiate to achieve this goal but also to bring such negotiations to a conclusion.

Although these combined activities have not yet produced a nuclear weapon–free world, they did play a key role in shaping a global political environment that has been conducive to stockpile reductions over the last twenty years, to the gradual delegitimization of such weapons (still a work in progress), and to the generation of practical proposals for achieving nuclear disarmament.

As a result, it is less common today to see nuclear disarmament summarily dismissed as utopian, impractical, or as Margaret Thatcher once said, “pie in the sky.”2

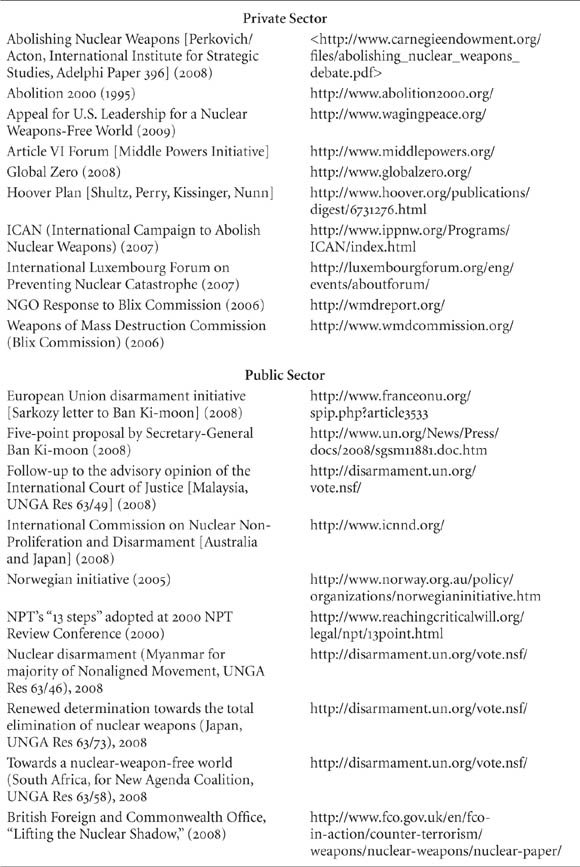

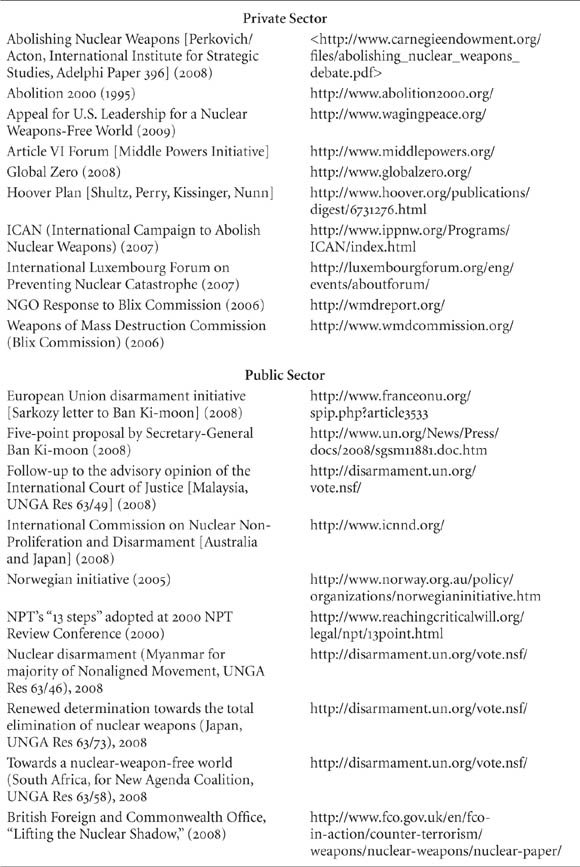

Nobody disputes that the January 2007 op-ed in the Wall Street Journal stimulated public interest in disarmament as a serious response to nuclear weapons threats. Since its publication there have been a cascade of disarmament proposals. The world today is arguably closer to a “tipping point” for new progress in nuclear disarmament than it is to a global nuclear weapon free-for-all, as some have feared (Table 2.1).3

These nuclear disarmament initiatives have come from many diverse sources. The approach of having former officials or statesmen publish op-eds on this issue has now been replicated in Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.4 More will likely follow. Newspapers around the world have published countless editorials in support of this goal. It was endorsed by both leading candidates in the 2008 U.S. presidential campaign, as well as by senior officials in virtually all other states that possess such weapons.

Several nuclear weapon states have taken some steps in the right direction, if not always officially linking this progress to their legal commitments under Article VI of the NPT. The French government has announced a significant cut in its arsenal, after having already shut down its nuclear test site along with its plants to produce fissile material for weapons. The British government has proposed a conference of experts from the nuclear weapon states to examine the challenge of verifying nuclear disarmament.

For their part, the United States and Russian Federation—which have more than 95 percent of the world’s nuclear weapons—concluded a new bilateral treaty on April 8, 2010, to replace the expired START treaty.5 The new treaty sets a ceiling for each side of 1,550 deployed strategic offensive nuclear warheads and limits their respective number of deployed delivery vehicles for such warheads at 700. The treaty fulfills joint commitments made by presidents Obama and Medvedev in 2009; in his April 5, 2009, speech in Prague, President Obama also stated a U.S. commitment “to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons,” adding that this would entail the pursuit of further reductions beyond the START follow-on treaty.6

These are just some of the efforts that are under way by states with nuclear weapons, efforts that by no means will alone produce global nuclear disarmament but that may help in achieving further reductions.

Other initiatives have come from diverse coalitions of states, consisting of what are often called the “middle-power states.” The New Agenda Coalition (Brazil, Egypt, Ireland, Mexico, New Zealand, Sweden, and South Africa) continues to advance its joint proposals for progress in nuclear disarmament, notably by means of annual resolutions in the General Assembly. The states behind the Norwegian initiative (Australia, Chile, Indonesia, Norway, Romania, South Africa, and the United Kingdom) have been advancing their own set of disarmament and nonproliferation proposals since 2005, focusing mainly on measures to strengthen the NPT.

Getting to Zero: Some Recent Initiatives

In the last few years a number of private groups and governments have offered proposals for moving toward nuclear disarmament. Some of the most prominent are listed below.

Several international coalitions of nongovernmental actors have also emerged in recent years to champion this cause, including long-standing efforts by Pugwash Conferences, which won the Nobel Peace Prize for its work on nuclear weapons in 1995.7 Other groups offering steps for disarmament include the Global Zero initiative, the International Luxembourg Forum on Preventing Nuclear Catastrophe, Mayors for Peace, and the Middle Powers Initiative and its Article VI Forum (organized by the Global Security Institute), as well as other coalitions focused more on building support at the grass-roots level, such as ICAN (the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons), Abolition 2000, the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation, and others too numerous to list here.

Various international commissions have also focused on the disarmament challenge, building on the earlier work by the Palme and Canberra commissions (1982 and 1996, respectively). In 2006 the international Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission chaired by Hans Blix issued a report with thirty recommendations dealing just with nuclear weapons.8 Two years later, Australia and Japan jointly launched the International Commission on Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament in a common effort to reinvigorate global efforts in these fields; its final report, issued in late 2009, produced seventy-six recommendations.9 Also noteworthy are the annual reports issued by the International Panel on Fissile Materials, an independent group of arms control and nonproliferation experts that since 2006 has been studying specific technical measures to control and dispose of weapon-usable nuclear materials.10

In 2008 the European Union sent a proposal to the UN secretary-general, outlining an eight-point initiative to address several nuclear weapon challenges, including disarmament. In December 2008, Javier Solana, the EU high representative for common foreign and security policy, addressed the EU disarmament and nonproliferation proposals at a conference held at the European Parliament.11

Nuclear disarmament is what Dag Hammarskjöld used to call a “hardy perennial” at the United Nations, which has served as a global forum for cultivating this perennial for over six decades. On October 24, 2008, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon delivered a major address devoted just to nuclear disarmament, the first such address by a UN secretary-general exclusively on this subject in many years. In December 2009, he issued his Action Plan for nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation, identifying several ways to implement his 2008 proposal.12 He has also raised this issue repeatedly in his official remarks at many multilateral gatherings, inside and outside the United Nations, and he even launched a multimedia Twitter, Facebook, and MySpace campaign called “WMD-WeMustDisarm” leading up to the International Day of Peace, September 21, 2009.13 On September 24, 2009, the UN Security Council held its first high-level summit to address nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation, which resulted in the adoption of Resolution 1887, though it dealt primarily with nonproliferation issues.

Meanwhile, efforts are continuing in the General Assembly to advance specific nuclear disarmament proposals, although they seldom receive the credit they deserve for their persistence and level of detail. These include specific resolutions on nuclear disarmament offered by Japan, Myanmar (on behalf of a majority of the Non-Aligned Movement), the New Agenda Coalition, and Malaysia (on a nuclear weapons convention).14 These resolutions are debated and adopted year after year by overwhelming majorities.

Nuclear disarmament has also been a specific focus of meetings that take place in NPT arenas, as registered, for example, in the thirteen “practical steps for the systematic and progressive efforts” to implement Article VI of the treaty, agreed at the 2000 NPT Review Conference. The 1995 NPT Review and Extension Conference politically tied the indefinite extension of the treaty to a package deal of commitments that included a “programme of action” relating to Article VI of the treaty and the Middle East Resolution, which called for efforts to establish a nuclear weapon–free zone in the region. Each of the 2007, 2008, and 2009 annual sessions of the Preparatory Commission for the 2010 NPT Review Conference also addressed nuclear disarmament issues in some depth, and each of these sessions also allowed for some participation by groups from civil society (including presentations, attendance at plenary meetings, and the distribution of publications).

In addition, nuclear disarmament has been the focus of several recent books that have helped to clarify the historical context, prescribe specific steps, and stimulate a dialogue between advocates and critics of disarmament.15 The entire Fall 2009 and Winter 2010 issues of Daedalus, the journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, were dedicated to the subject “On the Global Nuclear Future.”

Several points emerge from this brief survey of only a few of the many nuclear disarmament proposals that have emerged in recent years. First, these proposals come from a wide variety of sources, including very different types of countries—such as nuclear weapon states and coalitions of industrialized and developing states—as well as regional organizations and a growing number of diverse nongovernmental organizations. The champions of nuclear disarmament are not only non–nuclear weapon states and peace groups; literally all states profess to support this goal, as do growing numbers of current and former leaders of government and former military experts. The constituency of nuclear disarmament has significantly expanded in recent years to include the world’s religions, women’s groups, environmentalists, scientists, scholars, lawyers, human rights advocates, mayors, and legislators.

Second, although anti–nuclear weapon movements have historically placed a very heavy emphasis—best documented by Lawrence Wittner16—on the threats posed by such weapons and fears of their possible use, recent proposals are stressing such themes as the positive security benefits that would result for all countries from the elimination of such weapons. Meanwhile, more commentators are also stressing the military disutility17 or irrelevance of nuclear weapons in addressing security concerns in the twenty-first century, including terrorism, proliferation, the prevention of armed conflict within and between states, as well as many other emerging issues relating to cybersecurity, space weapons, and the development and transfers of conventional weaponry. Although appeals to fear and basic morality persist in many of these initiatives, there is also more of an emphasis on hope and the prospects for a safer world without nuclear weapons.

Third, there is much cross-fertilization among these various proposals. Many of their “steps toward zero” have long appeared in General Assembly resolutions. The four most fundamental criteria for assessing future nuclear disarmament initiatives—that is, that they should be verifiable, transparent, irreversible, and legally binding—have appeared for many years in these resolutions and in consensus documents agreed upon at meetings of representatives from the NPT states parties. Many of these criteria were addressed by groups

of governmental experts in reports requested by the General Assembly decades ago.

This process of cross-fertilization goes far beyond these basic principles and encompasses some very specific proposals. These most commonly include deep cuts in the largest nuclear arsenals, held by the Russian Federation and the United States; reductions in nuclear weapon delivery systems; the destruction of nondeployed weapons; the safeguarding of fissile material recovered from such weapons; the entry into force of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty and the start of negotiations on a multilateral fissile material treaty; disarmament actions by other states with nuclear weapons; the no-first-use doctrine; the withdrawal of nonstrategic nuclear weapons deployed outside national territories; de-alerting; security assurances for non–nuclear weapon states; adherence by the nuclear weapon states to the protocols of nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaties; parallel efforts to eliminate other types of weapons of mass destruction while limiting conventional arms; and numerous other confidence-building measures to facilitate the process of nuclear disarmament.

Fourth, a great weakness in these proposals—virtually all of them—is that they go only so far in specifying what specific actors must do in specific circumstances; in short, the proposals tend, with only rare exceptions, to avoid issues relating to the political tactics of implementation. For example, such proposals seldom, if ever, get into the weeds of the domestic politics of states to identify what new laws and regulations must be created to give greater weight to international commitments, or how specific governmental institutions need to be adapted to meet this challenge. Some proposals recognize the need to integrate international disarmament commitments into the domestic policies, laws, regulations, and bureaucracies of states, but they are typically silent on precisely how this is to be achieved. International commissions understandably have been reluctant to prescribe such reforms in specific states. More surprising is the reluctance of nongovernmental proposals to address these challenges. In short, the proposals are much stronger on what needs to be done than on how to do it.

Fifth, future proposals for global nuclear disarmament must do a better job of responding to criticisms that have been raised about the wisdom of pursuing zero.18 Critics say that the goal is utopian or impractical; that it is dangerous, encouraging states once covered by foreign nuclear umbrellas to seek their own nuclear deterrents; that it is irrelevant, because a given set of “bad countries” will inevitably seek nuclear weapons regardless of what the rest of the world does; that it is unenforceable (what would the world community really do if, in a nuclear weapon–free world, a state cheated and developed its own clandestine nuclear arsenal?); that it would open the door to large-scale conventional war; that it is unverifiable; and that it fails to understand that nuclear weapons are dangerous only when they are in the “wrong hands.” Also, most commonly, it must respond to the dictum that such weapons “cannot be dis-invented.”

All of these arguments have sound rebuttals. Former military leaders and nuclear weapon policy-makers have potentially much to contribute in clarifying the positive security benefits from disarmament and, above all, in exposing the many frailties of its alternatives.

Sixth, many of these zero initiatives suffer from zero follow-up. Meetings are held, various pieces of paper are issued, and that is that. The act of making such proposals has become an end in itself in some ways. Given that many of the proposals are quite similar, disarmament proponents might well examine more closely what has happened to past proposals, why they have not been implemented, or how they could be advanced through additional actions by governments and international organizations. This suggests the great importance of regular assessments of the consistency of empirical facts with agreed normative goals.

To promote accountability and compliance with past policy commitments, various public arenas already play important roles, and could well become even more relevant in the years to come as the nuclear arsenals continue to decline. With respect to nuclear disarmament, these especially include the various sessions of the NPT preparatory committees and once-every-five-years review conferences, which together comprise the NPT review process.19

One of the key decisions leading to the indefinite extension of the NPT in 1995 provided that the treaty review process “should look forward as well as back.”20 This is how accountability occurs in a multilateral treaty setting: behavior is assessed against agreed normative standards, which in the case of the NPT are found in the text of the treaty itself and in interpretative statements adopted by consensus at the review conferences. Another such multilateral arena is in the work of the UN General Assembly and its First Committee, which annually considers about fifty resolutions, including many that deal with specific measures to promote global nuclear disarmament. Complementary follow-up efforts and assessments can also occur within the governmental processes of individual states, through the oversight, speech, and debate functions of the legislatures; especially useful are assessments intended to ensure that a state’s laws, policies, and practices are in line with its international commitments.

Though the various arenas may differ, the essential process of accountability is largely the same, consisting of three fundamental components: commitment, behavior, and assessment. Much of the case for the eventual negotiation of a multilateral nuclear weapon convention follows very similar logic: an agreed disarmament norm is needed—in this case, agreement on the norm of zero. The norm has behavioral consequences. This behavior is authoritatively assessed through a procedure widely accepted as legitimate. And judgments are reached on the achievement of the intended purpose.

The process of accountability is very important both in confirming progress and in exposing departures from the agreed norm, especially since some of these departures—while originally intended to apply to single states—could well evolve into new multilateral norms. A good example is the often-proposed doctrine that would treat nuclear weapons as legitimate to possess for the “sole purpose” of deterring nuclear attacks.21 It remains to be seen whether current calls for such a doctrine would serve as a stepping stone toward—or away from—zero. One need only consider a world in which more and more states were acquiring their own nuclear weapons for this sole purpose, while current possessors defer disarmament indefinitely. A review and accountability process is therefore indispensable in identifying and preventing the evolution of new multilateral norms that are contrary to the goal of disarmament.

The seventh and final point about these proposals is their common tendency to ignore issues relating to the UN disarmament machinery (including the Conference on Disarmament), reforms that are needed, and its past contributions and successes in advancing disarmament. The United Nations serves as an indispensable arena for deliberating disarmament norms, for converting such norms into multilateral treaty obligations, for promoting their universality and legitimacy, and, of course, for establishing accountability.

This survey should leave little doubt that there has been a significant revival of worldwide interest in the goal of eliminating nuclear weapons worldwide. This revival is not limited to initiatives launched by individuals or groups in civil society; it is also manifested in efforts by states and coalitions of states.

Yet throughout the history of global nuclear disarmament efforts, the various “partial measures” that have been pursued have tended over time to become ends in themselves, as disarmament has typically been approached as a distant aspiration or “vision” rather than as a serious focus of public policy. More than thirty years ago, Swedish disarmament diplomat Alva Myrdal wrote of the “game of disarmament,”22 and there are indications that this game is still being played. With disarmament relegated to the status of a dream, concrete policy actions have tended to bear a closer resemblance to arms control than to disarmament. Thus the original twin goals agreed in the early years of the United Nations—namely, the elimination of all weapons of mass destruction and the regulation of conventional arms—have become switched, and much of the global effort now appears to be centered on regulating nuclear weapons.

Evidence for this is seen in the efforts by the nuclear weapon states to reduce the number of deployed strategic nuclear weapons and their delivery systems, to halt the global proliferation of such weapons, to strengthen controls and physical security over fissile materials, to tighten up export controls, and other such measures, while at the same time affirming the continued indispensability of such weapons for purposes of deterrence.

So the revival of nuclear disarmament as a goal does not necessarily translate into the revival of governmental efforts to achieve it. Such efforts would logically include the establishment of disarmament agencies in the nuclear weapon states, the adoption of domestic legislation and regulations specifically addressing disarmament, the development of national plans with timetables and benchmarks for achieving disarmament goals, the appearance of disarmament as line-items in national budgets, and the termination of research and development of modifications to existing weapons or efforts to “modernize” facilities constituting the nuclear weapon complex. The doctrine of nuclear deterrence has been modified here and there, but it remains viewed as an indispensable basis for security in about ten states directly, and tens more indirectly under the nuclear umbrella. There are no disarmament “complexes” or disarmament “stewardship programs.”

Yet virtually all of the various nuclear disarmament initiatives currently on the table have some potential to contribute in bridging this gap between future ends and current means. Different initiatives are obviously targeted at different constituencies. Policy-makers and experts in regional and international organizations will find much that is useful in the reports of the International Commission on Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament, and the International Panel on Fissile Materials. Meanwhile, the Global Zero Campaign, the International Campaign Against Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), Abolition 2000, the Women’s International League of Peace and Freedom, and countless other civil society groups aim at wider audiences. Religious groups that will surely

continue to promote disarmament include Pax Christi, the Quakers, Soka Gakkai International, and the World Council of Churches, to name only a few.

The transition from affirming the goal of disarmament to achieving it will occur only if there is sufficient political will, which is most likely to be found in the union of a compelling idea with diverse political actors willing to advance it.

Future efforts to rid the world of nuclear weapons—to achieve zero—will therefore succeed or fail depending on the outcome of two parallel trends. The first is the achievement of an international consensus on certain substantive issues relating to nuclear weapons per se—namely, their irrelevance as military instruments, the security hazards posed by their very existence, their cost, the human and environmental consequences of their production and use, and their widespread identification as an anathema rather than as a source of prestige or status. The second is a multidimensional political process to build and sustain such a consensus, a process involving, in various ways, the participation of individual citizens, nongovernmental groups, political parties, mayors, national legislators, and regional and international organizations. Navigating to zero, in short, requires both an anchor (a stable goal) and a sail (some dynamic means of propulsion).

Zero will not be achieved strictly by the action of elites nor by an exclusive reliance on many other worthy but insufficient measures, including those relating to nonproliferation, safeguards, physical security controls over nuclear materials, and other such activities. Together, these are better viewed as complementary means to advance disarmament. The great advantage of the zero-norm is that it offers a universal, nondiscriminatory standard, which makes it far more likely to obtain the international cooperation and consent needed to achieve full compliance and sustainability.

Yet many still believe that nuclear weapons will be around forever—that they have “kept the peace”; that they represent the triumph of national genius over the forces of nature; and that they offer the ultimate protection against fearsome threats emanating from a violent and unpredictable world that exists in an enduring, immutable condition of anarchy. Pax atomica, they say, is here to stay.

Perhaps George S. Patton had the best response. He wrote in a 1933 paper on military tactics: When Samson took the fresh jawbone of an ass and slew a thousand men therewith he probably started such a vogue for the weapon . . . that for years no prudent donkey dared to bray. . . . History is replete with countless other instances of military implements each in its day heralded as the last word—the key to victory—yet each in its turn subsiding to its useful but inconspicuous niche. Today machines hold the place formerly occupied by the jawbone, the elephant, armor, the long bow, gun powder, and latterly, the submarine. They too shall pass.23

This chapter is based on an article that originally appeared in the April 2009 issue of Arms Control Today, and is published here with the permission of the Arms Control Association.

1. International readers might not know that Rip van Winkle is a fictional character who appeared in a short story by Washington Irving about a lazy farmer in New York who sleeps for twenty years through the U.S. Revolutionary War. In the present article, he sleeps even longer. George P. Shultz, William J. Perry, Henry A. Kissinger, and Sam Nunn, “A World Free of Nuclear Weapons,” Wall Street Journal, 4 January 2007, p. A15. The same authors later published “Toward a Nuclear-Free World,” Wall Street Journal, 15 January 2008, p. A13; and “How to Protect Our Nuclear Deterrent,” Wall Street Journal, 19 January 2010, p. A17.

2. Margaret Thatcher, interview cited in Geoffrey Smith, “Thatcher to Reagan: Put Some Hindsight in Summit Vision,” Los Angeles Times, 14 November 1986.

3. For a contrary view, see William J. Perry and James R. Schlesinger et al., “America’s Strategic Posture: The Final Report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States” (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, 2009), which made twelve references to the impending nuclear “tipping point.” See also “The Nuclear Tipping Point,” a documentary film released in January 2010 by the Nuclear Security Project, in coordination with the Nuclear Threat Initiative and the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, and the press release describing the film at http://www.nti.org/c_press/press_release_NTP_012710.pdf.

4. For links to each of these statements, see http://www.pugwash.org/reports/nw/ nuclear-weapons-free-statements/NWFW_statements.htm.

5. “Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms,” at http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/140035.pdf.

6. Texts of the Prague speech of 5 April, the Joint Statement of 1 April, and the Joint Understanding of 6 July are available at www.whitehouse.gov.

7. The Pugwash Council identified eleven steps for nuclear disarmament in its statement issued after the 57th Pugwash Conference in 2007. See www.pugwash.org/reports/ pac/57/statement.htm.

8. Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission, Weapons of Terror: Freeing the World of Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Weapons (Stockholm: Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission, 1 June 2006), at www.wmdcommission.org/files/Weapons_of_Terror.pdf.

9. Gareth Evans and Yoriko Kawaguchi (co-chairs), Eliminating Nuclear Threats: A Practical Agenda for Global Policymakers (Canberra and Tokyo: International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament, November 2009).

10. International Panel on Fissile Materials, “Global Fissile Material Report 2009: A Path to Nuclear Disarmament” (Princeton: International Panel on Fissile Materials, 2009).

11. Javier Solana, “European Proposals for Strengthening Disarmament and the Non-Proliferation Regime,” Address, European Parliament, Brussels, 9 December 2008, at www.eu-un.europa.eu/articles/en/article_8354_en.htm.

12. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, “Secretary-General, at Breakfast Meeting, Spells Out Steps to ‘Move Ball Forward’ on Nuclear Disarmament, Non-Proliferation Ahead of Review Conference,” Press Release SG/SM/12661, 8 December 2009, at http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2009/sgsm12661.doc.htm.

13. “Secretary-General Launches Multiplatform Campaign to Promote Nuclear Disarmament and Non-proliferation,” UN Press Release DC/3179, 13 June 2009, at http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2009/dc3179.doc.htm.

14. On 18 January 2007, and on the request of Malaysia and Costa Rica, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon circulated their draft Model Nuclear Weapons Convention to member states as an official UN document, A/62/650.

15. Examples include Bruce Larkin, Designing Denuclearization (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2008); George Perkovich and James M. Acton, Abolishing Nuclear Weapons: A Debate (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment, 2009); and Barry M. Blechman and Alexander K. Bollfrass (eds.), Elements of a Nuclear Disarmament Treaty (Washington, DC: Stimson Center, 2010).

16. Lawrence Wittner, The Struggle against the Bomb (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995, 1997, 2003).

17. See Ward Wilson, “The Winning Weapon? Rethinking Nuclear Weapons in Light of Hiroshima,” International Security 31, no. 4 (Spring 2004): 162–79; and Wilson, “The Myth of Nuclear Deterrence,” Nonproliferation Review 15, no. 3 (November 2008): 421–39.

18. There are notable exceptions. See John Holdren, “Getting to Zero: Is Pursuing a Nuclear-Weapon-Free World Too Difficult? Too Dangerous? Too Distracting?” Discussion Paper 98-24 (Cambridge, MA: Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, April 1998), at http://belfercenter.ksg.harvard.edu/publication/2919/getting_to_zero. html.

19. For a further discussion of the NPT review process and accountability, see Jayantha Dhanapala with Randy Rydell, Multilateral Diplomacy and the NPT: An Insider’s Account, UNIDIR/2005/3 (Geneva: UN Institute for Disarmament Research, 2005), pp. 115–42.

20. “Decision 1: Strengthening the Review Process for the Treaty,” NPT/CONF.1995/32 (Part 1), Annex, para. 7, at www.un.org/disarmament/WMD/Nuclear/1995-NPT/pdf/ NPT_CONF199532.pdf.

21. Several publications support this “sole purpose” doctrine, including William J. Perry and Brent Scowcroft (Chairs), U.S. Nuclear Weapons Policy, Independent Task Force Report No. 62 (New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 2009); and Federation of American Scientists, Natural Resources Defense Council, Union of Concerned Sciences, Toward True Security: Ten Steps the Next President Should Take to Transform U.S. Nuclear Weapons Policy (Washington, DC: Union of Concerned Scientists, 2001, 2008) at http://docs.nrdc.org/nuclear/files/nuc_08021201A.pdf.

22. Alva Myrdal, The Game of Disarmament (New York: Pantheon Books, 1976).

23. “Notable & Quotable,” Wall Street Journal, 14 November 1995, p. A14.