The transformation of the U.S. conventional capabilities has begun to have a substantial and important impact on counterforce strike missions, particularly as they affect counterproliferation requirements. So too have improvements in ballistic missile defense programs, which are also critically central to U.S. counterproliferation objectives. These improved conventional capabilities come at a time when thinking about the prospects of eventually achieving a nuclear disarmed world has never been so promising. Yet, the path toward achieving that goal, or making substantial progress toward it, is fraught with pitfalls, including domestic political, foreign, and military ones. Two of the most important impediments to deep reductions in U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals—no less a nuclear disarmed world—are perceived U.S. advantages in conventional counterforce strike capabilities working in combination with even imperfect but growing missile defense systems.

The Barack Obama administration has already toned down the George W. Bush administration’s rhetoric surrounding many of these new capabilities. Nevertheless, it is likely to affirm that it is a worthy goal to pursue a more conventionally oriented denial strategy as America further weans itself from its reliance on nuclear weapons. The challenge is to do so in the context of a more multilateral or collective security environment in which transparency plays the role it once did during the Cold War as a necessary adjunct to arms control agreements. Considerable thought has already been devoted to assessing many of the challenges along the way to a nuclear-free world, including verifying arsenals when they reach very low levels, more effective management of the civilian nuclear programs that remain, enforcement procedures, and what, if anything, might be needed to deal with latent capacities to produce nuclear weapons.1 But far less thought has been expended on why Russia—whose cooperation is absolutely essential for abolition to happen—might ever wish to proceed toward such a postnuclear world that would be dominated militarily by American conventional military capabilities and what might be needed to allay legitimate concerns in this regard. At the very least, it will become increasingly important to separate fact from fiction in regard to the state of various conventional offensive and defensive counterproliferation capabilities and begin the challenge of addressing what kind of concrete steps are needed to alleviate Russian concerns. It is precisely that objective to which this chapter is addressed.

The chapter is organized along the following lines. It first examines Russian perceptions of U.S. advances in conventional warfighting, after which it then assesses the extent to which these perceptions are real or exaggerated. Finally, in light of Russia’s concerns, the chapter closes with a set of policy options designed to help allay these concerns along the path toward deep reductions in nuclear arsenals.

Confronted by both the U.S. lead in conventional capabilities and the erosion of its nuclear forces due to readiness reductions coupled with lapses in its early warning system, Russia has evinced a growing sense of vulnerability. Although this threat perception is only partly justified, it still could impede further steps in achieving deep nuclear reductions. To achieve its ambitious objectives in nuclear arms control, the Obama administration must first understand and then try to alleviate legitimate Russian fears concerning asymmetric American advantages in conventional counterforce capabilities.

American advances in precision global strike capabilities coupled with a seemingly unfettered ability to exploit missile defense technologies in the absence of any treaty constraints provides a challenging backdrop to obtaining deep reductions in Russian and American nuclear arsenals. The cavalier way in which the Bush administration unilaterally opened negotiations with Poland and the Czech Republic on stationing midcourse interceptors and radars, re spectively, on these nations’ territories catapulted the missile defense issue to center stage. But equally worrisome to Russia are developments in precision conventional strike weapons that are seen as capable of destroying strategic targets. Russia sees the combination of conventional offense and defense as leaving it at a decided and uncomfortable disadvantage vis-à-vis the United States in the aftermath of deep nuclear reductions, no less a world without nuclear weapons.2

Controversy surrounding the U.S. decision to negotiate rights to deploy a “third site” for midcourse ground-based interceptors in Poland and the X-band radar in the Czech Republic made missile defense the premier issue standing in the way of progress in deep nuclear reductions. Indeed, Premier Vladimir Putin told Japanese media on May 10, 2009, that U.S. plans for missile defenses in Europe would be linked to strategic arms reductions.3 Despite the limited technical capacity of U.S. interceptors in Poland to threaten Russian strategic forces, Russia’s reaction to U.S. plans was vitriolic for reasons that go beyond technical threat analysis.4 The Bush administration’s discussions with the Poles and Czechs occurred against the backdrop of NATO’s inchoate plans for a missile defense system of its own, including one that could conceivably include Russia at some future point. In January 2008, with Germany as the host nation, NATO’s Theater Missile Defense Ad Hoc Working Group—operating under the aegis of the NATO-Russia Council—conducted the fourth in a series of theater missile defense exercises, with eleven NATO nations joining Russia in a command and control exercise of missile defense forces. Some might forgive Russians for believing that the U.S. rush to deploy its own missile defense system in Europe represents a way of edging Russia out of any future NATO missile defense system.

Russia might also be excused for worrying about the open-ended U.S. approach toward determining when to deploy new missile defense components as well as the opaque nature of what the U.S. notion of global missile defenses truly means. Missile defense opacity reflects the diametrically opposed acquisition strategies for missile defense practiced before and after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Before 9/11, particularly in regard to Democratic administrations, support for any complex military system occurred only after the threat had been amply explicated and then the system was subjected to thorough testing—a “fly-before-you-buy” practice in which any particular missile defense system undergoes enough operational tests to determine its reliability and performance effectiveness.5 The administration of George W. Bush intro duced the notion of capabilities-based planning, which overturned the need for a thorough vetting of the threat and instead sought to develop a full range of capabilities needed to cope with likely future contingencies. The logic for capabilities-based planning was laid out in the 2001 Quadrennial Defense Review.6 It was predicated on the belief that, since one cannot know with enough confidence precisely what threats will emanate from either nations or terrorist groups, defense planners must identify specific capabilities needed to dissuade enemies from pursuing threatening options, deter them by deploying forces for rapid use, and defeat them if deterrence fails. With such a broad writ in hand, the chief lesson of 9/11 for the Bush administration was that a determined adversary would stop at nothing—including even acquiring ballistic missiles—in order to attack the United States.7 With long-standing metrics for measuring performance no longer applicable, the Bush administration abjured relying on extensive flight tests to determine system reliability and performance. Deployment decisions were based instead on simulations that integrated limited real-world test results with conceptual components reproduced in a model. Moreover, no longer did the Missile Defense Agency specify an overall system architecture. Whatever components passed the muster of this admittedly risky approach were deployed immediately in two-year block intervals, leaving critics aghast at such a something-is-better-than-nothing approach to deployment. But to observers in Russia, such opacity produced confusion and uncertainty with respect to future U.S. missile defense plans and capabilities.8

Moscow’s more immediate concerns have changed in the face of the Obama administration’s revisions to the Bush plans and the 2010 NATO decision to offer Russia inclusion in NATO’s plans for territorial missile defenses in Europe. With its decision to scrap the Bush plan to protect Europe and America from Iranian intercontinental-range missiles, the Obama administration quite sensibly has chosen to focus initially on defending against missiles that could threaten American troops in Europe and our European allies: Iranian short- and medium-range ballistic missiles. These missiles are numerous and threatening and to that extent substantially more interceptors than the Bush plan’s ten will be needed to deal with this near-term threat. Thus, the Obama plan’s missile defense architecture will depend on proven sea-based interceptors—Standard Missile-3 (SM-3)—deployed initially on ships but later also on land. One Aegis cruiser alone carries 100 SM-3 interceptors. The Obama plan banks on the expectation that Iran will not produce a truly intercontinental missile threat until at least 2020, by which time modified versions of SM-3 interceptors are expected to be capable of intercepting potential future intercontinental-range ballistic missiles (ICBMs).9 Still, absent legal constraints on future American missile defense plans, Russian fears, however relaxed today, could re-emerge in the future.

What animates Russian officials most in light of the absence of formal treaty constraints is that with the U.S. deployment of highly powerful ground- or sea-based X-band radars and space-based infrared sensors (known as the Space-Based Infrared System, or SBIRS-Low), America will have a break-out potential in place for a thick, global system of missile defense.10 Compared with the poor discrimination performance of earlier warning radars, X-band systems have a resolution of 10 to 15 cm, good enough to discriminate between real warheads and decoys. More ominously, once they are deployed globally, not only will midcourse ground-based interceptors be able to take advantage of their improved resolution, but so too will a growing network of sea-based interceptors on Aegis cruisers/destroyers and land-based upper-tier THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense) interceptors. Of course, X-band, and especially SBIRS-Low, may not prove to be as effective as promised, but this does not lessen the concern of Russian defense planners who see uncontrolled expansion of American global missile defenses as a potential threat to their diminishing nuclear deterrent.

Prospective missile defense advances represent only the most visible impediment to progress in nuclear arms control. Lurking just behind are concerns about U.S. advanced conventional weapons. In the U.S. debate, much has been made of Russia’s fear of U.S. nuclear primacy.11 But Russian strategic analysts have begun to write in some detail about the prospects that future advanced conventional weapons—together with improved missile defenses—could place Russia in a position of unacceptable vulnerability.12 This perception is not merely the product of wild speculation by nonspecialists in the Russian press. The well-respected Maj. Gen. Vladimir Dvorkin (Ret.), who formerly directed fundamental research in mathematical modeling in nuclear planning, and then participated in virtually every major U.S.-Soviet strategic arms control negotiation, reflects the broad concern now existing in Moscow that conventional weapons imbalances represent a key roadblock to deep nuclear reductions. As Dvorkin notes:

[A Russian] concern is the possibility that high-precision conventional weapons could be used to destroy strategic targets. Precision-guided munitions (PGMs) pose a threat to all branches of the strategic nuclear triad, including the silo and mobile launchers of the Strategic Rocket Force (SRF), strategic submarines in bases, and strategic bombers. The types of PGMs to be used against each of these components, the vulnerability of these components, the vulnerability of assets, and operation requirements would require . . . study.13

U.S. plans to arm Trident D-5 missiles with conventional payloads as part of its plans for prompt global strike have already raised concerns—in the United States and Russia alike—about missile warning ambiguity and inadvertent retaliatory actions. These developments are of sufficient concern to Russian planners that Moscow arms officials have proposed strategic conventional delivery vehicles as candidates for possible limits in future strategic weapons treaties with the United States.14

If U.S. strategic conventional denial capabilities are just emerging today, Russian military planners must also worry about where such programs might be in a decade or two. The U.S. Strategic Command’s initial complement of forces comprising the Global Strike mission included the U.S. Air Force’s F-22 fighter providing penetration corridors for B-52, B-1, and B-2 bombers loaded with conventional precision strike weapons.15

The U.S. Navy has converted four of its 18 Trident Ohio-class submarines to each carry 154 Tomahawk land-attack cruise missiles, the latest version of which features a two-way satellite data link that permits the missile to attack one of sixteen preprogrammed targets or take new GPS coordinates to attack a fleeting target of opportunity. Assuming it has reserve fuel, the missile can also loiter in the area for hours awaiting a more important target, as well as pass information from its own TV camera on battle damage. Instead of filling each of the four Trident submarines with its full complement of 154 Tomahawks, a few missiles can be traded for special-operations mini-subs or small reconnaissance UAVs. The Pentagon has also sought, without success thus far, to spend $503 million to outfit a small number of the Trident D-5 nuclear missiles on the remaining fourteen Ohio-class Trident submarines with conventional warheads (either small-diameter bombs or bunker-buster penetrating warheads). Even more robust global strike systems could emerge from current research and development programs, including the Conventional Strike Missile, consisting of pairing converted ICBMs with hypersonic glide vehicles launched from locations on the east and west coasts of the United States not associated with nuclear delivery, and two experimental hypersonic technology programs.16

Any American president—Barack Obama included—wishing to wean the United States from its long-standing reliance on nuclear weapons would find it difficult not to pursue a robust conventionally oriented denial strategy. Yet, the challenge facing the United States is to make more transparent precisely where current advanced conventional and missile defense programs stand today, and what restrictions or operational constraints the United States might be willing to accept, if any, on their development or operation to accelerate the path toward nuclear abolition.

If the U.S. decision to arm a small number of Trident D-5 missiles with conventional warheads is any indication, virtually no thought went into how such plans would be viewed in Moscow or Beijing, or indeed, even in the U.S. Congress. The impervious nature of conventional strategic strike programs is less a matter of intention and more related to the fact that programs are mired in vagueness with differing interpretations of missile requirements and capabilities existing within various bureaucratic stake holders. Programs are diffused across the entire Department of Defense, including the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency and the military services. And rather than being driven by any well-conceived concept of operation dictating how these various programs will transform military operations—the bellwether of truly revolutionary change—these efforts are propelled for the most part by raw technological momentum.17 The opaque nature of U.S. global missile defense ambitions in the Bush administration largely emanated from the imperative to deploy systems as quickly as possible to meet political, if not threat-driven, needs. Global strike capabilities, on the other hand, have the advantage today and in the future of appearing to transform deterrence-oriented nuclear ballistic missiles that no one ever wishes to be used into denial-oriented counterforce systems possessing an array of future mission possibilities—a factor that surely animates the interest of all three military services. But Global Strike’s exclusive affiliation with advanced conventional strike is today more promise than reality. However much the U.S. Air Force may have envisioned the Prompt Global Strike mission as a decidedly conventional one, its initial implementation proved otherwise, not least because of the dearth of truly global conventional capabilities.18 In fact, Global Strike’s June 2004 implementation as an approved operational plan mirrored the Bush administration’s 2001 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) conflation of nuclear and conventional capabilities.

President Bush’s elevation of preemption (actually, prevention) from military option to national doctrine in 2002 gave real impetus to making the Global Strike concept operational. Grave concern over the toxic mix of WMD and the presumed nexus between so-called rogue states and a new brand of apocalyptic terrorism led to specific guidance to the U.S. military to integrate selected bombers, ICBMs, ballistic-missile submarines, and cyber-warfare assets into a strike force capable of promptly attacking high-value targets associated with specific regional contingencies. Some advanced conventional capability figured into the original Global Strike operational implementation, probably consisting of joint direct attack munitions launched by B-2 bombers and Tomahawk cruise missiles launched from submarines and surface vessels. But Global Strike as a purely conventional capability was overtaken not only by limited capabilities but also by the Bush administration’s desire to make nuclear strike options more credible and tailored to the post–Cold War requirements reflected in its

2001 NPR.19

Where does Prompt Global Strike stand today? The Next-Generation Bomber, originally slated for deployment by 2018, has been delayed not only because of budget limitations but also due to uncertainties with respect to what kind of impact current Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) renewal will have on the mix of nuclear delivery systems.20 According to a congressional staff member on the Senate Armed Services Committee, there is no longer any prospect for either Trident or Minuteman land-based nuclear missiles undergoing conversion to meet the Pentagon’s requirement for prompt conventional strikes, while research funding for hypersonic glide vehicles will remain in place, but without prospect for any deployment decisions any time soon.21 As one senior U.S. Strategic Command officer stated to this writer recently, “Global Strike has been throttled back.”22 Yet the Obama administration’s 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review promotes the expansion of long-range conventional strike capabilities, including experimenting with new Prompt Global Strike prototypes, perhaps even ones that would avoid, unlike the Bush administration’s plans for Trident conventional conversion, intermingling nuclear and conventional warheads together.23

One might argue, of course, and the Russians do, that the requirement for converting Trident might be resurrected in future. They surely observed that an independent study panel of the bipartisan National Research Council (NRC) had endorsed a limited application for the conventionally armed Trident before the 2008 election. The NRC panel only gave its support for the mission of a time-critical strike against a fleeting target of opportunity (for example, counterterrorist target or rogue state activity), which would involve no more than one to four weapons. The U.S. Navy had pressed for funding to convert two Trident missiles on each of twelve deployed Trident submarines for a total of twenty-four conventionally armed Tridents. Importantly, the NRC panel drew a distinction between the more limited mission and conventional Trident’s broader application. The limited use would not carry the same stiff operational and political demands as a larger use of conventional Trident would in providing leading edge attacks in support of major combat operations. In the latter regard, Trident would probably join substantial numbers of Tomahawks and other PGMs on bombers as part of a counterforce strike at the outset of a major regional contingency. The NRC panel properly noted that in contrast to using one to four Tridents alone, any large-scale prompt conventional strike would present much stiffer operational demands related to intelligence support and command and control, as well as drastically different political implications with regard to warning ambiguity. Whether the contingency involves using one or many conventional Tridents, as the NRC panel observed, “[T]he ambiguity between nuclear and conventional payloads can never be totally resolved.”24 Yet, the larger the Trident salvo of conventional missiles, the higher the prospects for misinterpretation and inadvertent responses. At the same time, because Russian early-warning systems are incomplete, even smaller numbers may be wrongly interpreted as a larger-than-actual salvo or incoming missiles. Concerns about ambiguity leading to inadvertent nuclear war—rightly or wrongly conceived—largely explain the congressional decision not to support conventional Trident’s funding.

Arming Trident with a conventional warhead is not the only way to deal with fleeting terrorist targets. For example, the combination of U.S Special Forces on the ground and armed Predator UAVs in the air represents a potent and now broadly used new capability to deal with fleeting targets. The NRC panel noted the importance of UAVs and special forces as sources of intelligence supporting conventional Trident strikes, which begs the question: why can’t less provocative capabilities—if perhaps less effective under some circumstances—obviate the need for conventional Trident in regard to this limited mission?25 Another option to evaluate would be a new missile altogether, rather than one with a nuclear legacy, like the U.S. Navy’s concept of a “Sea-Launched Global Strike Missile,” or even the Navy’s effort to develop a supersonic version of the Tomahawk cruise missile.26 For the time being, the Obama administration and Congress have taken an appropriate time out with Prompt Global Strike, which will surely not allay Russian concerns over the long run. But it does provide space to consider future prompt-strike missile options and their effect on military stability in the context of a world that may well become far less dependent on long-range, nuclear-armed ballistic missiles in the future.

Research and development programs attempting to achieve technological breakthroughs in global strike capabilities by 2025 are, frankly speaking, problematic at best. These include the hypersonic cruise vehicle that could take off and land from a U.S runway and be anywhere in the world in one to two hours. The idea for such a space plane has been around since the 1950s.27 President Ronald Reagan accelerated the push in his 1986 State of the Union Address, yet his director of the Strategic Defense Initiative (Star Wars), Henry Cooper, told a congressional panel in 2001 that after the expenditure of some $4 billion on the development of the space plane concept from the early 1970s to the end of the 1990s (discounting various programs in the 1950s and 1960s, as well as the space shuttle investment), the only thing produced was “one crashed vehicle, a hangar queen, some drop-test articles and static displays.”28 Current Pentagon hypersonic programs face, among many, the difficult challenge of developing lightweight and durable high-temperature materials and thermal management techniques needed to cope with hypersonic speeds. This is because hypersonic glide vehicles require a thermal protection system capable of preventing their payloads from melting at re-entry speeds of up to Mach 25 (or twenty-five times the speed of sound). The quest to master and deploy hypersonic systems will not come easily, not only because of the huge technical challenges associated with these systems but also because the strategic environment is so uncertain. No defense agency would likely be willing to bet on any one solution to the global-strike requirement under such circumstances. However, the U.S. Congress appears to have chosen to continue down the risky and potentially costly path of pursuing hypersonic delivery vehicles. If nothing else, this course removes the nearer-term solutions like conventional Trident from becoming any kind of impediment to progress in strategic arms control negotiations.

If converting Trident to deliver non-nuclear payloads and development of more futuristic advanced conventional programs represent nonexistent threats to Russia today, that is not the case in regard to hundreds of Tomahawk cruise missiles (616 maximum, if UAVs or special forces are not fitted out in launch tubes instead) that comprise the four Ohio-class Trident submarines converted from nuclear ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) to guided-missile (that is, cruise missile) submarines between 2002 and 2008. In worrying about this threat, Russian analysts take particular note of the precision accuracy and retargeting capability of the latest generation Tomahawk cruise missile. This, it is asserted, means that highly accurate Tomahawks could threaten Russian silobased intercontinental ballistic missiles, while the fact that they possess their own means of reconnaissance, can loiter in the target area, and can be retargeted after launch, suggests they can find and destroy mobile missiles like the new Topol-Ms. Such a preemptive strike of this sort could, by 2012–15, destroy between 70 and 80 percent of Russian’s nuclear forces. The remaining missiles, it is asserted, could then be readily intercepted by the U.S. global missile defense system.29

Granting that the current state of Russian strategic missile forces is today substantially below its Cold War form and that they are likely to suffer funding shortfalls over the next decade, the expectation that U.S. conventionally armed Tomahawks, even ones with high accuracy and retargeting capability, could, on their own, accomplish such successful results is—kindly put—the height of excessive imagination. Observing U.S. advances in precision conventional strike linked to advanced reconnaissance systems, Soviet-era military theoreticians did indeed become fascinated with the prospect that “automated search and destroy complexes” could one day come close to approximating the effectiveness of at least tactical nuclear weapons.30 But a closer look at what Soviet-era planners truly had in mind shows that it had nothing to do with anticipating that missiles alone could dominate a major military campaign. Instead, their role was seen as leveraging the effectiveness of a multiplicity of other strike elements (aircraft, bombers, electronic jamming, airborne assault and heliborne forces, and so forth) in a major combined arms campaign. Tomahawk cruise missiles are surely accurate enough to hit on or very near to a Russian missile silo, but their warhead carries only 450 kg of either blast fragmentation or combined-effects submunitions. The former is a mere pinprick vis-à-vis hardened missile silos; the latter is only relevant against soft targets. Indeed, even a Trident missile armed with a conventional penetrator would require Herculean accuracy and absolutely perfect targeting conditions to have any chance whatsoever of threatening silo-based missiles.31

What about advanced Tomahawk’s reputed new capabilities against mobile missiles? As discussed earlier, the U.S. Air Force in particular has accomplished major improvements in counterforce targeting of fleeting targets, largely as a by-product of nearly continuous combat operations in Afghanistan and Iraq over the last eight years. Nevertheless, it is critical to distinguish between what piloted aircraft can accomplish against a rogue state’s mobile missiles compared with autonomous missiles equipped with a data link and TV camera facing arguably the most skilled nation there even has been when it comes to operating intermediate- and strategic-range mobile missiles.32 It’s one thing to track, detect, and successfully attack fleeting groups of Taliban or al Qaeda fighters in Afghanistan or Iraq, or Iraqi mobile missile units who believed they are impervious to ubiquitous battlefield reconnaissance systems while being otherwise overwhelmingly dominated (in the case of Iraq in 2003) by large numbers of American conventional forces, and quite another to expect 600 or so conventionally armed Tomahawks to do decisive damage to 180 Russian nuclear-armed mobile missiles proficient in the practice of employing camouflage, cover, and concealment methods once they have moved from their peacetime bases. Moreover, there is the stiff challenge of operating impervious to Russia’s advanced air and missile defenses. U.S. counterforce targeting against mobile missiles has indeed improved greatly since coming up completely short in the 1991 Persian Gulf War, but even in Iraq in 2003, only anecdotal evidence suggests that more success was achieved against a greatly diminished Iraq missile force compared to its 1991 holdings. Success did not mean halting the admittedly low launch rate over the twenty-one-day war, nor did it mean that Iraq’s entire missile stores were eliminated via either counterforce or missile defenses by the war’s conclusion. For example, thirty-three Iraqi cruise missiles—a threat that had surprised American missile defenders and contributed to friendly-fire losses—were found intact on the Faw peninsula after the war.33 Simply put, we fall prey to a fallacy of division to think that because tactical counterforce operations using advanced strike systems (like Tomahawk) have improved remarkably during the last eight years, they can also succeed in strategic counterforce operations where even nuclear strike systems were expected at best to provide only problematic results due to inevitable target location uncertainties.34 Finally, there is the stark reality that the inevitable failure to locate and destroy all of Russia’s strategic nuclear weapons would expose the United States to a devastating nuclear riposte.

The open-ended nature of the U.S. missile defense system raises perhaps the most legitimate area of concern from a Russian perspective, although the Obama administration’s decision to cap ground-based midcourse interceptors at thirty ought to allay such concerns. Vladimir Dvorkin has written that Russia has little to worry about from American missile defenses until roughly 2015. Until then, Russian offensive missiles have adequate “defense suppression systems” to require as many as ten U.S. ground-based interceptors to destroy one warhead. Even the addition of the third site in Poland would not have changed these circumstances. But as time passes, and if the United States were to deploy space-based laser and kinetic-kill weapons “on a massive scale,” Russia’s nuclear deterrent could conceivably be seen to be at risk.35 Given the stance of the Obama administration thus far, notably its insistence on demonstrating missile defense performance and system cost effectiveness before deployment decisions are taken, the likelihood of the United States taking the path that worries Russians most is highly doubtful. Yet, without the constraints once associated with the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, from which the United States unilaterally withdrew in 2002, nothing legally bars a future U.S. administration from pursuing such an open-ended course of action. This stark reality no doubt explains Russian insistence on including, in the text of the “New” START treaty, signed in Prague on April 8, 2010, by presidents Obama and Medvedev, a clause noting the interrelationship between strategic offense and defense, and its growing importance as offensive systems are further reduced.36

The daunting challenge of achieving complete abolition of nuclear weapons will surely entail several stages of nuclear reductions along the path to lower, and one hopes, safer arsenals. And dealing with conventional imbalances along this uncertain path not only is a U.S.-Russian dilemma but also includes conventional imbalances in the Middle East, South Asia, and Northeast Asia. Within these three regional settings lately, a contagious outbreak of interest in preemptive strike doctrines linked to advanced conventional strike weapons (most notably cruise missiles) shows worrisome signs of producing even greater instability in the future.37 For many states on the unequal end of such developments, it will be difficult to imagine why they would wish to eliminate their nuclear weapons. Former Senator Sam Nunn suggests the need to reach a “base camp [or] vantage point from which the summit [a nuclear-free world] is visible and the final ascent to the mountaintop is achievable.”38 The first step along the way to that base camp is for the United States and Russia to restart a critical feature of Cold War arms control negotiations: the elevation of transparency, or making both sides of any competition aware, within the limits of security, of what the other side is doing.

The notion of greatly improved transparency and perhaps even substantial cooperation between the United States and Russia is not a novel concept; it rose to center stage after 9/11. In November 2001, the two presidents signed a “Joint Statement on a New Relationship between the United States and Russia,” followed by another in May 2002 specifying a range of possibilities for cooperative engagement, including strengthening confidence and increasing transparency in the area of missile defenses, exchanging information on missile defense programs and tests, reciprocal visits to observe tests, and work on bringing a joint center for exchanging data from early warning systems into effect. Most important, the two sides agreed to study possible areas for missile defense cooperation beyond joint exercises to include joint research and development on missile defense technologies within the limits of security and protecting property rights. The Russia-NATO Council was singled out as the framework to examine cooperative engagement in missile defense.39

What greeted Moscow in the aftermath of the 2002 attempt to foster missile defense cooperation with the United States was little in substance and provocative instead of cooperative, namely Washington’s unilateral engagement of Poland and the Czech Republic on their involvement in the U.S. missile defense program. U.S. efforts to bring Georgia and Ukraine into NATO didn’t help either. U.S. attempts to allay Russia’s concerns about these developments failed to impress, and gestures toward transparency and an examination of the potential contribution of Russian radars were less than wholeheartedly dealt with, at least in Russian eyes.

The first step in achieving real and lasting cooperation in missile defense is for Russia and the United States, through the NATO-Russia Council, to reach consensus on pace and scope of Iran’s ballistic and cruise missile threat to the whole of NATO. Extant threat assessments facing the NATO region focus in the main on ballistic missile systems. The debates focus less on Iran’s ballistic missile capacity than on the pace of Tehran’s success in weaponizing a suitably compact nuclear reentry vehicle that could survive the rigors of reentry, as well as how quickly their solid-fuel missile developments will mature. Far less attention is given to the growing cruise missile threat on the periphery of Europe. Iran is among a rapidly growing number of countries that have begun pursuing land-attack cruise missile programs. According to a 2004 NATO Parliamentary Committee report, Iran was converting some 300 Chinese anti-ship cruise missiles into land-attack systems by fitting them with turbojet engines and new guidance systems. Such designs have been demonstrated as capable of achieving around 1,000 km range and could be readily launched from merchant ships to target substantial portions of Europe. Even more worrisome over the longer-term was the 2005 disclosure that Russian and Ukrainian arms dealers had collaborated with the head of Ukraine’s export control agency in the illegal sale of twelve to twenty Ukrainian/Russian Kh-55 strategic (and nuclear capable) cruise missiles to China and Iran. The Kh-55’s range is 3,000 km. Even though the illegal transfer of at least six Kh-55s to Iran also included a ground support system for testing, initializing, and programming the missiles, such a small number of cruise missiles was probably acquired primarily for purposes of examination and reverse engineering, leading eventually to the development of Iran’s own long-range cruise missile program.40 A common view of the threat of both ballistic and cruise missiles offers opportunities for broader cooperation beyond just ballistic missile defense to include warning, detection, and defeat of airborne threats.

U.S. cruise missile defense programs today are not in good shape. Fighters equipped with advanced detection and tracking radars will eventually possess some modest capability to deal with very low volume attacks, assuming advance warning information is available. But existing U.S. programs are underfunded, while interoperability, doctrinal, and organizational issues discourage the military services from producing joint and effective systems for defending U.S. forces and allies in regional military campaigns.41 NATO’s own cruise missile defenses are no better off. The poor state of cruise missile defenses raises the question: can either or both the U.S. and Europe find security by fielding only half a missile defense system, capable of handing but one dimension of the missile threat?

Launched within the NATO-Russia Council in 2002, the CAI’s goal is to achieve a system of air traffic information exchange along the borders of Russia and NATO member countries. Four sites each currently exist in Russia and NATO countries—from the far north in Russia (Murmansk) and Norway (Bodø) to Turkey (Ankara) and Russia (Rostov-on-Don) in the south. Poland hosts a NATO coordination center in Warsaw, while the companion Russian center is located in Moscow. Besides forming a basis for NATO and Russia to establish greater confidence in working together, the CAI has focused especially on aircraft that might be under the control of terrorists or a rogue state. CAI is complemented as well by a functionally equivalent system of Air Sovereignty Operation Centers (ASOC) that the United States funded in former Warsaw Pact states beginning in 1997. Although the CAI information exchange system had successfully passed joint testing qualifications in July 2008, it along with other bilateral NATO-Russia initiatives were suspended in August 2008 in protest for Russia’s intervention in Georgia. CAI only resumed in March 2009.42

CAI, working in possible cooperation with the ASOCs, could form the basis for investigating an expansion of air monitoring capabilities to the domain of cruise missile warning and defense. Russia initially balked at the formation of ASOCs, arguing that they together could create a common airspace picture useful for tracking and providing guidance against threats. But to the extent CAI starts taking on the character of ASOCs, the closer it gets to becoming a useful NATO-wide and Russian vehicle for starting collaboration on defending against cruise missiles. About $6.5 million has been invested in CAI thus far, with financial support coming from twelve countries, including Russia and the United States.43 The virtue of engaging Russia’s participation in an expanded CAI concept—including its role in cruise missile defense—goes much beyond trust building and improved air safety and security. Rather, an expanded CAI offers Russia the chance to become a full participant in an inchoate but potentially constructive endeavor to kick-start the lesser-included dimension of missile defense. Russia’s long-standing prowess in developing effective air defense systems, including the S-400, which boasts capability to intercept ballistic and cruise missiles as well as aircraft, could fit nicely into a broad-area concept for European cruise missile defense. Directing Moscow’s export energies away from S-300 and S-400 transfers to countries like Syria and Iran and toward the prospect of a more effective collaborative working environment within the NATO-Russia Council is worthy of serious evaluation.

There is already broad support in Washington for engaging Russia in a manner substantially different from the Bush administration’s efforts in early 2008 by both secretaries Gates and Rice. Perhaps the easiest way to jump-start missile defense cooperation would be to move toward implementing the Joint Data Exchange Center in Moscow. Russia and the United States first agreed on a joint warning concept involving notifications of ballistic missile flights to each side in 1998, which was formalized in a June 2000 meeting between presidents Clinton and Yeltsin, who agreed to establish the center in Moscow. Legal and tax issues have prevented the center from becoming operational. All of the operational details have been worked out already, so movement toward implementation should be comparatively straightforward. It would also be appropriate to examine more closely Russian president Putin’s 2007 proposal to establish a second data exchange center in Brussels.

U.S. officials have already signaled their willingness to examine the use of Russian low-frequency warning radars at Gabala in Azerbaijan and Armavir in Russia’s Krasnodar Region as part of the U.S.-led global missile defense system.44 As nongovernmental radar specialists have noted, there is a chance that combining an X-band radar deployed either in Azerbaijan or Turkey with the Armavir radar could possibly offer three to four more minutes of additional warning than the canceled X-band radar operating on its own from the Czech Republic.45 At the very least, American radar specialists need to investigate precisely how these two radars might contribute not only to improved missile defense performance but also partnerships with Russia in areas where Russian technological prowess might complement American and European missile defense skills.

If cooperation in missile defense warning isn’t difficult enough, it is even more so when it comes to cooperation in interceptors. Security and intellectual property rights issues have always stood in the way of achieving much progress. Assuming, however, that U.S.-Russian relations improve in the aftermath of successful strategic arms control treaties, and particularly in light of NATO’s offer to include Russia in its territorial missile defense program, it would make good sense to explore avenues toward cooperation in missile defense interceptors. One competitive advantage that Russia once had is in directed energy technologies. In the early 1990s, U.S. and Russian technical cooperation exchanges disclosed that Russia then led the world in carbon dioxide and high-power solid-state lasers. Again, in the 1990s at least, there was significant cooperation between U.S. and Russian scientific and academic organizations, including in the area of solid-state lasers for nonmilitary applications.46 The U.S. missile defense program has experienced less than optimal success in the airborne laser program—witness the recent Pentagon decision to cancel the second prototype—an effort seen as critical to achieving some modest capability in defeating ballistic missile threats shortly after they are launched (or during the so-called boost phase). Building on past endeavors in the 1990s, it makes good sense to explore once again opportunities to cooperate in directed energy interceptors.

The purest form of reassurance would resurrect formal arms control constraints designed to allay Russian (and Chinese) concerns about the open-ended nature of the U.S. global missile defense program. Foremost on Russian minds are U.S. intentions to deploy interceptors in space, which could perform double duty as both ballistic missile interceptors, with potentially significant capabilities against Russian offensive forces in the aftermath of deep reductions, and antisatellite weapons to maintain or extend American dominance in space. The American pursuit of such options would be foolhardy, in the first case because no conceivable rogue-state threat would merit such an expansion, and in the latter case, because American dependence on space to sustain its conventional superiority would potentially suffer from such a decision to trigger an arms race in antisatellite weapon capabilities. A preferred alternative would be for the United States to examine what it might be willing to accept in limits on midcourse and upper-tier interceptors, which could be incorporated in a new legally binding treaty with Russia. At the same time, the United States should take the lead with Russia and China to negotiate “rules of the road” for space operations akin to ones that govern air, ground, and naval operations on earth.

Were the Iranian nuclear missile threat to the U.S. homeland to accelerate unexpectedly, which is doubtful, and reasons for deploying the third site in Poland and the Czech Republic determined to be necessary, it is not inconceivable to imagine a significant degree of Russian cooperation nonetheless. This would entail dusting off the assurance proposals of the Bush administration, introduced in 2007, which involved restricting the radar’s angle of view so as not to threaten Russian missile launches and agreeing not to activate the site until the Iranian threat was palpable to both sides. Russia had also insisted on a permanent observer presence at both the Czech and Polish bases, but one well-placed Russian observer has suggested that a Polish proposal, allowing for an “almost permanent presence” by Russians, would be satisfactory to Moscow. This would entail aperiodic visits by Russian observers who would be accredited to the Russian embassies in the Czech Republic and Poland and the installation of surveillance cameras for around-the-clock surveillance.47

This area is perhaps the most intractable, not least because of the Russian tendency to exaggerate U.S. military capabilities. There is little doubt that America possesses greatly superior conventional military forces capable of being pro jected anywhere around the globe. Russia is today investing in its conventional forces and plans, by 2020, to be in a much better state than it is today. But even the most optimistic estimates suggest that Russia will remain significantly inferior across the board vis-à-vis the United States. From this vantage point Russia is less concerned about the reasons why current U.S. conventional capabilities, such as conventionally armed Trident missiles or hundreds of highly accurate Tomahawk cruise missiles launched from Trident submarines, are incapable of threatening Russia’s strategic deterrent. They are concerned about future possibilities, however “fanciful.”48

If there is a solution to the conventional superiority issue, it lies less in trying to convince Russia that current or prospective U.S. advanced conventional strike systems are incapable of achieving what they fear, and more in conceiving of options that might allay those concerns over the longer run. That said, as much transparency as is possible should nonetheless take place. But so too should the United States evaluate the possibility of constraining the patrol areas where Ohio-class Trident submarines bearing Tomahawks go. Russian analysts are concerned that they will operate sufficiently close to Russian territory to permit them to target their fixed and mobile strategic forces. Indeed, such an operational pattern is not fanciful in light of the speed and quietness of the Ohio-class family of submarines. They could quite conceivably, though not without some risk, operate with impunity not only inside a state’s 200 nm exclusive economic zone but also within its 12 nm territorial waters.

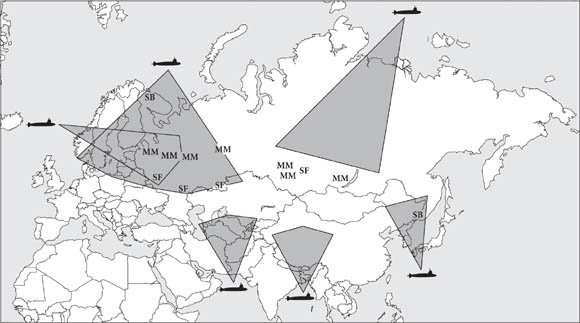

To evaluate what the United States would have to do to allay Russian concerns, I examined what constraining Ohio-class submarines to a patrol area just outside the 200 nm economic exclusive zone might accomplish to reduce the perceived threat of striking all Russian strategic nuclear forces (fixed and mobile forces together with submarines bases), comprised of thirteen large-area targets.

Assuming that Tomahawks have a maximum operational range of 2,500 km, Ohio-class submarines would be able to reach nine of the thirteen target areas. Importantly, however, three mobile divisional bases (housing today ninety-nine Topol mobile missiles), and two fixed strategic missile groups (with sixty-eight SS-18 missile silos, each missile armed with ten independently targetable warheads)—together representing 57 percent of Russia’s land-based Strategic Rocket Forces—would not be within reach of Tomahawk missiles. Although such an approach seems unnecessary based purely on the highly dubious nature of the Tomahawk threat to such strategic targets, U.S. planners should examine in much greater detail the merits and pitfalls of employing such an operational constraint in order to allay Russian fears.49

On possible constraints in regard to future U.S. ambitions to restart the conventional arming of Trident for a prompt global strike task, or a broader mission to engage significantly in regional military campaigns, the only solution may lie in counting such strategic conventional delivery vehicles as if they were nuclear armed, which seems to be the case for ICBMs and SLBMs under the “new” START regime signed in April 2010. The same may have to apply as well to future hypersonic cruise vehicles, not least because in fact they would be theoretically capable of delivering nuclear payloads.

As U.S. and Russian planners look toward the challenges and pitfalls of achieving deep reductions in nuclear arsenals, they should begin systematically to appraise additional novel ways of achieving stability as arsenals drop to less than 500 warheads and then fall further. The recent turn by many states toward adopting preemptive strike doctrines employing advanced conventional weapons does not augur well for achieving a stable world. However difficult it surely will be for states to shed this predilection toward preemption—or prevention—through prompt action, if history tells us anything, it is that while such practices may succeed in achieving some initial battlefield success, they do so at the grave cost of war and its inevitable political and financial consequences. Witness America’s eight-year tragedy in Iraq. Preemptive strike doctrines employing conventional weapons are clearly unacceptably dangerous in a nuclear-armed world. But they will also be dangerous in a world devoid of all nuclear weapons, particularly during regional or international crises. One way is to tone down, if not eliminate, the preemption option, as the Obama administration did in its May 2010 National Security Strategy.50 It is needlessly reckless to elevate such a military choice—assessed as absolutely critical under dangerously threatening circumstances—to a national doctrine.

Another is to undertake a fresh examination of Ronald Reagan’s dream of eliminating offensive ballistic missiles, attempted unsuccessfully at the Reykjavik summit with Mikhail Gorbachev, in 1986.51 However fanciful such an endeavor may appear today, it may begin to become far more meritorious as the world sheds its nuclear obsession. Land-attack cruise missiles, which today have already become the conventional weapon of choice around which preemptive strike doctrines are being wrapped, also merit much more attention than they have received to date. Besides more effective controls within supply-side mechanisms like the Missile Technology Control Regime, and incorporation of cruise missiles into the Hague Code of Conduct’s normative treatment of missile proliferation,52 all advanced conventional system transfers will merit much closer attention than ever before, perhaps along the lines of global arms trade treaty, a concept that has already been examined closely at the UN. Common international standards, accompanied by greatly improved transparency and verification procedures attending the transfer of all advanced conventional systems, are matters that cannot await the outcome of contemporary efforts to achieve nuclear abolition. They deserve attention on their own merits no matter the outcome of the quest to achieve the abolition of nuclear weapons.

This chapter is adapted and updated from a longer treatment of the subject, entitled “The Path to Deep Nuclear Reductions: Dealing with American Conventional Superiority,” Proliferation Papers No. 29 (Paris, Ifri, Fall 2009). It can be downloaded at www.ifri.org/downloads/pp29gormley1.pdf.

1. These issues are usefully taken up in George Perkovich and James M. Acton, Abolishing Nuclear Weapons, Adelphi Paper 396 (New York: Routledge for the International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2008).

2. For a comprehensive treatment of Russian perceptions of growing U.S. military superiority, see Stephen J. Blank, Russia and Arms Control: Are There Opportunities for the Obama Administration? (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2008).

3. “Russia to Link Missile Defense in Europe with Nuclear Arms Treaty,” RIA Novosti, May 10, 2009.

4. For a technical appraisal of how Russian military analysts might plausibly view Polish-based interceptors as a threat, see George N. Lewis and Theodore A. Postol, “European Missile Defense: The Technological Basis of Russian Concerns,” Arms Control Today (October 2007), at http://www.armscontrol.org/act/2007_10/LewisPostol.

5. For an illustration of this position from a practitioner, see “What Are the Prospects, What Are the Costs? Oversight of Ballistic Missile Defense (Part 2),” testimony of Philip E. Coyle, III, Senior Advisor, World Security Institute, before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, Subcommittee on National Security and Foreign Affairs, April 18, 2008.

6. Quadrennial Defense Review Report, September 30, 2001, at http://www.defenselink.mil/pubs/pdfs/qdr2001.pdf.

7. For this author’s analysis of 9/11’s lessons, see Dennis M. Gormley, “Enriching Expectations: 11 September’s Lessons for Missile Defence,” Survival 44 (Summer 2002): 19–35.

8. Maj. Gen. Vladimir Dvorkin (retired), observed that “there is no telling how far the United States will go with its missile defense deployment plans.” See his “Reducing Russia’s Reliance on Nuclear Weapons in Security Policies,” in Engaging China and Russia on Nuclear Disarmament, ed. Christina Hansell and William C. Potter, Occasional Paper no. 15 (Monterey, CA: James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, April 2009), p. 95.

9. “Fact Sheet on U.S. Missile Defense Policy: A ‘Phased, Adaptive’ Approach for Missile Defense in Europe,” The White House Office of the Press Secretary, September 17, 2009.

10. This was a concern even before the U.S. withdrawal from the ABM treaty in 2002. See Jack Mendelsohn, “The Impact of NMD on the ABM Treaty,” in White Paper on National Missile Defense, ed. Joseph Cirincione et al. (Washington, DC: Lawyers Alliance for World Security 2000).

11. Most notable was the reaction in both the U.S. and Russia to a 2006 article in Foreign Affairs magazine arguing that the U.S is close to obtaining an effective nuclear first-strike capability against Russian and Chinese strategic retaliatory forces. See Keir A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press, “The Rise of U.S. Nuclear Primacy,” Foreign Affairs (March/ April 2006), at http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/61508/keir-a-lieber-and-darylg-press/the-rise-of-us-nuclear-primacy. For reactions, see “Nuclear Exchange: Does Washington Really Have (or Want) Nuclear Primacy?” Foreign Affairs (September/October 2006), at http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/61931/peter-c-w-flory-keith-payne-pavel-podvig-alexei-arbatov-keir-a-l/nuclear-exchange-does-washington-really-have-or-.

12. See, for example, “U.S. Can Attack Russia in 2012–2015,” Moscow Agentstvo Voyennykh Novostey (internet in English), February 26, 2008 [FBIS].

13. Dvorkin, “Reducing Russia’s Reliance on Nuclear Weapons in Security Policies,” p. 100. For its part, Russia would prefer to proceed along the conventional-oriented path that the United States has pursued since 1991. Russia’s National Security Concept, published in 2000, notes that reliance on nuclear weapons is a temporary phenomenon. Once current plans to develop new air- and sea-launched cruise missiles and PGMs come to fruition by 2020, Russia will no longer need to rely predominantly on nuclear weapons for deterrence purposes. See Nikolai N. Sokov, Jing-dong Yuan, William C. Potter, and Cristina Hansell, “Chinese and Russian Perspectives on Achieving Nuclear Zero,” in Engaging China and Russia on Nuclear Disarmament, ed. Hansell and Potter, p. 4 (see n. 8).

14. The United States reportedly would prefer to keep any conventionally armed delivery systems, like Trident, out of future nuclear arms control treaties. Author interview with a former government official, Washington, DC, April 2009.

15. It should be noted that when the Global Strike mission was first constituted, it counted nuclear weapons among its constituent components.

16. These programs are joint U.S. Air Force/DARPA efforts conducted under the rubric “Force Application and Launch from CONUS [Continental United States]” or FALCON program. See http://www.darpa.mil/tto/programs/Falcon.htm for a brief outline of the FALCON program; and Alternatives for Long-Range Ground-Attack Systems (Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office, March 2006), at http://www.cbo.gov/ ftpdocs/71xx/doc7112/03-31-StrikeForce.pdf.

17. The development of the aircraft carrier during the 1930s furnishes perhaps the finest exemplar of concept rather than technology driving revolutionary military innovation. See Williamson Murray and Allan R. Millett, eds., Military Innovation in the Interwar Period (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), chs. 5, 8.

18. For a pre-9/11 view of U.S. Air Force plans, see Matt Bille and Maj. Rusty Lorenz, “Requirement for a Conventional Prompt Global Strike Capability,” briefing presented to the National Defense Industrial Association’s Missile and Rockets Symposium and Exhibition, May 2001 (copy available from this chapter’s author).

19. For an incisive appraisal of the operational implementation of Global Strike, including the creation of its organizational components to direct planning and execution, see Hans M. Kristensen, “U.S. Strategic War Planning after 9/11,” Nonproliferation Review 14 (July 2007): 373–90.

20. Bombers are credited with counting rules that apply to capability rather than actual operating load-outs of nuclear weapons. Thus, there is currently a reluctance to firm up a Next-Generation bomber design before START counting rules are made clear. See David Fulghum, “USAF Bomber Grounded by More than Budget,” Aviation Week & Space Technology (April 22, 2009), at http://www.aviationweek.com/aw/generic/ story.jsp?id=news/NGB042209.xml&headline=USAF%20Bomber%20Grounded%20b y%20More%20than%20Budget&channel=defense. For details on the new bomber, see Norman Polmar, “A New Strategic Bomber Coming,” Military.com (April 14, 2008) at http://www.military.com/forums/0,15240,165805,00.html.

21. Telephone interview, April 2009. My thanks to Monterey Institute colleague Miles Pomper for this information.

22. Interview, March 2009.

23. See Department of Defense Quadrennial Defense Review Report, February 2010, at http://www.defense.gov/QDR/images/QDR_as_of_12Feb10_1000.pdf. On new Prompt Global Strike concepts, including ones offering opportunities for increased transparency with Russia, see David E. Sanger and Thom Shanker, “White House Is Rethinking Nuclear Policy,” New York Times, February 28, 2010, p. 1.

24. “Conventional Prompt Global Strike Capability,” letter report of the National Research Council’s Committee on Conventional Prompt Global Strike Capability, dated May 11, 2007, at http://www.nap.edu/catalog/11951.html.

25. A point made by Joshua Pollack in “Evaluating Conventional Prompt Global Strike,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 65 (January/February 2009): 13–20. The less effective circumstances would entail Predator’s problematic survival against sophisticated and thick air defenses, which would be less likely to be the case in the limited counterterrorist scenario and more likely in major combat operations against a regional adversary.

26. The Sea-Launched Global Strike Missile is mentioned in “Conventional Prompt Global Strike Capability,” while a related (if not precisely the same) concept for a Submarine-Launched Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missile is discussed in detail at http://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/systems/slirbm.htm. On the supersonic Tomahawk, see Dennis M. Gormley, Missile Contagion: Cruise Missile Proliferation and the Threat to International Security (Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, 2008), p. 54.

27. The first publicly acknowledged program, in 1957, was the U.S. Air X-20 DynaSoar, which was supposed to be launched vertically off the ground and then glided back to earth for landing. The current hypersonic cruise vehicle would be expected to operate at between 30 and 50 km altitude.

28. Testimony by Henry F. Cooper to the House Subcommittee on Space and Aeronautics Committee on Science, October 11, 2001, at http://www.tgv-rockets.com/press/ cooper_testimony.htm. Cooper largely placed blame on Pentagon management inefficiencies for the program’s poor performance.

29. “U.S. Can Attack Russia in 2012–2015,” Moscow Agentstvo Voyennykh Novostey (Internet in English), February 26, 2008 [FBIS].

30. Most notably, see N. V. Ogarkov, Krasnaya Zvezda, May 9, 1984 (BBC Monitoring Service translation [SU/7/639/C/10]).

31. Russian concrete silo covers are dome-shaped and approximately 20 feet in diameter and 5 feet high in the center. This means that they have a radius of curvature of about 12.5 feet. Employing the targeting requirement of approaching the target at less than 2 degrees from the vertical, the penetrator would have to impact less than 5 inches from the absolute center of the silo cover, or within a 10-inch diameter circle whose center is at the apex of the dome. My thanks to Dr. Gregory DeSantis, a former U.S. Department of Defense scientist, for making these calculations based on the penetrator design discussed in Nancy F. Swinford and Dean A. Kudlick, “A Hard and Deeply Buried Target Defeat Concept,” Defense Technical Information Center document no. 19961213 060, 1996 (Lockheed Martin Missiles & Space, Sunnyvale, CA) at http://www.stormingmedia.us/86/8678/A867813.html.

32. The Soviet Union first deployed intermediate-range ballistic missiles on mobile launchers in 1976 (the SS-20).

33. Dennis M. Gormley, “Missile Defence Myopia: Lessons from the Iraq War,” Survival 45 (Winter 2003/04}, p. 71.

34. The Russian supposition that American intelligence, surveillance, and recon naissance capabilities are so ubiquitous that anything that moves will be detected and instantly killed flows from the exaggerated expectations of such books as Harlan Ullman and James P. Wade, Jr., Shock and Awe: Achieving Rapid Dominance (Washington, DC: National Defense University, 1996). For a more grounded treatment, see Barry Watts, Clausewitzian Friction and Future War (Darby, PA: Diane Publishing Co., 2004).

35. Vladimir Dvorkin, “Threats Posed by the U.S. Missile Shield,” Russia in Global Affairs 2 (April–June 2007), at http://eng.globalaffairs.ru/numbers/19/.

36. Text of the “Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms,” p. 2. The text also takes note of the impact of conventionally armed ICBMs and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) on strategic stability.

37. This trend is documented in Gormley, Missile Contagion (see n. 27).

38. Quoted in Philip Taubman, “The Trouble with Zero,” New York Times, May 10, 2009, at http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/10/weekinreview/10taubman.html.

39. Text of “Joint Declaration on the New Strategic Relationship,” The White House Office of the Press Secretary, May 24, 2002.

40. Gormley, Missile Contagion, chs. 3, 4.

41. Ibid., ch. 9.

42. Brooks Tigner, “NATO and Russia Near Air Traffic Information Exchange,” International Defence Review (April 29, 2009), at http://idr.janes.com/public/idr/index. shtml. See also press release of the Russian Mission to NATO, at http://natomission. ru/en/societ/article/society/artnews/40/.

43. The other sources of financial support include Canada, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Norway, Poland, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. See ibid.

44. Ellen Barry, “U.S. Negotiator Signals Flexibility toward Moscow over New Round of Arms Talks,” New York Times, May 5, 2009; and “U.S. Is Ready to Discuss Proposal on Using Gabala Radar as Part of Global Missile Shield—U.S. Ambassador,” Moscow Inter-fax, April 27, 2009.

45. See, for example, Theodore Postol, “A Ring around Iran,” New York Times, July 11, 2007, at http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/11/opinion/11postol.html. Postol argues that the Gabala radar’s lower frequency radar could crudely yet effectively provide earlier warning than a Czech-based X-band radar, whose higher frequencies and resolution are useful to characterize the target initially detected by the Russian radar. Thus, the sum of the two could furnish additional warning time without loss of much-needed target resolution.

46. K. Scott McMahon, Pursuit of the Shield: The U.S. Quest for Limited Ballistic Missile Defense (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1997), pp. 251–52.

47. Victor Yesin, “Action and Counteraction,” Global Affairs 1 (January–March 2009), at http://eng.globalaffairs.ru/numbers/26/1262.html. Yesin is a colonel general in the Russian military and a professor at the Russian Academy of Military Sciences.

48. A word used by Ambassador Linton Brooks to describe a practice employed by Soviet-era arms control negotiators, and apparently no less today. Brooks notes that a senior Russian official once noted that Russia was concerned over the possibility of U.S. use of special forces to blow up strategic missile silos. See his comments at an Arms Control Association meeting in Washington, DC, on April 27, 2009, at http://www.armscontrol.org/node/3632.

49. Johan Bergenas of the Monterey Institute’s James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies designed and constructed Figure 17.1. Even were these submarines to operate from within territorial waters, it is important to note that such cruise missiles would not be programmed to fly a straight-line path to their targets for reasons of survivability. Moreover, were they able to reach mobile missile operating areas, there would be little fuel remaining for advanced Tomahawks to employ their loiter and search capability against mobile missiles.

50. See http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/rss_viewer/national_security_ strategy.pdf.

51. For a recent appraisal, see Steve Andreasen, “Reagan Was Right: Let’s Ban Ballistic Missiles,” Survival 46 (Spring 2004): 117–30.

52. For reasons why adopting changes in the Hague Code of Conduct make sense, see Dennis M. Gormley, “Making the Hague Code of Conduct Relevant,” issue brief, July 20, 2009, at http://nti.org/e_research/e3_hague_conduct_relevant.html.