The topic of the first chapter is the evolution of the funerary monument that bears the epitaphs. The funerary epigram was inscribed on the base of statues; in the case of the stelai, whether decorated or not, the epigram could be on the base or the body of the stele. This monument was in turn placed within a very specific setting, the necropolis, although funerary monuments have also been found in private settings, for example when families opted to bury their dead on their country estates.1 I will briefly review the characteristics of these memorials, to help us better understand when and why the funerary monument evolved from a simple stone that marked the place of burial, to an iconic element with statues and reliefs that evoke the deceased. The final part of this chapter will refer also to funerary legislation, particularly the laws attributed to Solon; although they are not sumptuary laws in the strict sense, they do make a mark on the archaeological funerary landscape.

The necropolis is a world of the dead that also reflects the world of the living. The study of the necropolis can help us to understand how a society is organized according to different classes of age, gender and wealth or social status. Our investigation begins with the funerary monuments of the sixth century BC and extends through the end of the fourth century BC, but it is advisable to review briefly the customs prior to this time, taking note of any indications of age, gender and status.2

Funerary customs were not exactly alike in all regions of Greece. Our study is based especially on material from Attica. In the Geometric age (c. 900–700 BC), as in the Archaic and Classical periods, both cremation and burial were customary. However, changes in preferences and customs can be detected from one period to another. Throughout the ninth century BC we find secondary cremation, in other words, a custom whereby the ashes remaining from cremation are collected from the pyre and placed in an amphora that afterwards is deposited in the pit with grave-goods; this in turn is covered with a small tumulus. Already around this time there is a verifiable difference between the graves of adults and of children,3 adopted apparently in all regions of Hellas: children were buried, not incinerated, and in Athens they were usually buried in the area of the future Agora and not in the Kerameikos.4 A symbolic code is also followed in order to distinguish male tombs (funerary neck-handled amphora and war-related grave-goods: spearheads, swords) from female tombs (funerary belly-handled amphora and grave-goods related to feminine adornment: spindles, gold jewellery). The fact that, in Attica, women’s graves display no less wealth than men’s, is a unique case in the Greek Iron Age. In the same period, male graves begin to predominate in the Kerameikos, and in the opinion of François de Polignac, this necropolis became a place for commemorating the public status of certain men. In other words, a selective access to funerary rites is already perceptible within the elite group.

As we enter the eigthth century BC, we observe a trend toward burial, although cremation continues as an aristocratic custom, following the well-known hero ritual – Patroclus, Hector – which will be recovered in the following century. The vessels that mark tombs become increasingly monumental in form, an innovation possibly due to aristocratic insistence on public commemoration for all their members, women included, whereas this privilege was previously reserved for a group of deceased males of the Kerameikos. The richest tombs are most prevalent in the rural demes.

With the beginning of the Archaic period, through the seventh century BC, we observe a number of important changes in funerary customs.5 Again we find cremation as the dominant practice, and we observe, especially in the Kerameikos necropolis, a restriction that excludes children and women from the practice of formal burial – an expression used to indicate the type of burial that can be analysed archaeologically.6 In this century, of the two types of Attic grave, those of adults and those of children, differences are seen in the method of burial (inhumation in the case of children, cremation for adults) and in the type of pottery found in the graves, when there are grave goods (Subgeometric pottery for children, Orientalizing pottery for adults). The archaeologist James Whitley, who has studied this matter in detail, suggests that formal burial of adults was in fact for men, evoking heroic funerary practices; if this is so, there would no longer be any place for female symbolism, and Attica would lose its uniqueness, rejoining the rest of Iron Age and early Archaic Greece, with customs that distinguish only between the graves of male adults and the graves of children. In this century, the grave-goods to which I have alluded are quite scarce; however, in connection with male graves we almost always find the placement of external offerings (the German term Opferrinnen has been adopted). These are not grave-goods strictly speaking, but rather cult offerings.7 Within these constructions we find evidence of the celebration of funerary banquets, including large quantities of pottery; these were most likely deposited and covered after being used in the cult celebration. Over the course of the seventh century BC, this became the usual practice in the Kerameikos; by the end of the century it had extended to other parts of Attica, and this custom makes it reasonable to interpret such remains as indication of some kind of tomb cult, according to Whitley. All the data point unmistakably to clearly political and elite connotations of the funerary space, monopoly of the agathoi, throughout the seventh century BC.8

As we pass to the sixth century BC, there are a few changes, but less abrupt than in the previous century. Cremation is no longer the norm in adult burials, and graves once again become the place where the deceased is left with his grave-goods. By contrast, Opferrinnen are much less frequent: the custom of constructing such repositories was already unusual around 600 BC, and became very rare by the middle of the sixth century BC. The vessels that marked tombs disappear for the most part; in contrast, we find stone stelai and statues of youths, kouroi and korai.9 With the appearance of the kore, linked to the clan-based aristocracy, the tombs of women recover their individuality, although only unmarried young women receive this recognition. Also worth mentioning is that the funerary monuments and inscriptions of this period are usually found associated with groups of tumuli throughout Attica, in areas such as Vourva, Velanideza (the Aristion stele), Anavyssos (the Kroisos kouros). While it is possible to speak of aristocratic family tombs in relatively small complexes such as Vourva, studies emphasize that Archaic and Classical burials in the Athenian necropolis of the Kerameikos did not follow any family-related pattern, but rather that of age or status. The enormous tumuli that were raised in the Kerameikos between 560 and 540 BC do not represent any blood relations, but instead are groupings according to status, groups with some shared identity – men who had drunk and fought together and were buried together — and so confirm the particular role of this necropolis as manifesting public funerary ideologies, distinct from family customs.10 Women would have no representation here.

The archaeological evidence of sixth-century BC Athens reveals a city where ostentation prevails in certain funeral ceremonies. In the Kerameikos, about 580 BC, a new mound was built over the seventh-century mounds, inaugurating a new series of burials, which culminated in the gigantic Mound G (c. 555–550 BC).11 The same ostentation is also seen in the Agora, where an enormous Cycladic marble sarcophagus was discovered within a large complex of Archaic tombs, dated between 560 and 500 BC.12 Due to its exceptional nature, at a time when graves were no longer placed within the city, this sarcophagus has been hypothesized as the tomb of the Peisistratids.13

Beginning in 500 BC, according to D’Agostino, the city intensifies its control over funerary manifestations, and interest in figured stelai declines; there is no hesitation even to reuse these stelai in building the walls of Athens, under Themistocles.14 Around the timeframe of 490–440 BC, the state instituted public speeches in Athens for the war dead, and was in charge of their commemoration in stone monuments, referring to the monuments that stand along the road to the Academy, sometimes bearing inscriptions, in the area known as demosion sema.15

Despite the doubts raised by some scholars, it is difficult to question the existence of this space in which orators commemorated the thousands who fell in war, a place in which speeches and public celebrations served to interpret the past, express shared values and build a collective identity for the city.16 With regard to the exact location of this public cemetery, there are two possibilities. The general idea is that it was beside a road leading from the city to the Academy, but which one? Most scholars think that the cemetery was set on the wide road that issued from the Dipylon Gate, but others have suggested that it was beside the road that issued from the Leokoriou Gate, to the east of the Dipylon Gate, and ran parallel to the Academy Road deviating slightly in the direction of the demos of Hippios Kolonos. Archaeological excavations seem to indicate that the demosion sema was beside the former, that known as the Academy road. Thus, the establishment of this public cemetery is linked to clearly political motives: ‘In establishing the demosion sema near the Academy road, the demos defined a new funerary space. The choice was motivated in part by the road’s web of cultural associations, but it also drew a deliberate contrast with the district immediately to the east, along the Leokoriou roads where aristocratic values were celebrated. The Leokoriou roads had a noble, elite history, frequently expressed through association with horses and horsemanship. These roads were a particularly appropriate place for such aristocratic rhetoric because they were physically and conceptually linked to the hallowed ground of Hippios Kolonos, where, together with the hero-knight Kolonos, Poseidon and Athena were worshipped in their guise as horse deities.’17 Burying together those fallen in war was a custom that harked back to the Archaic practice just mentioned, where, in the mid-sixth century BC, groups linked by social and not family ties are buried together in large tumuli such as found in the Kerameikos.

While the road to the Academy had particular political and cultural importance for men, the gates of the city which opened onto routes linked with female religious activities became established as burial grounds for children: the Sacred Gate, opening the way to Eleusis; the Eriai Gates,18 leading to the sanctuary of Demeter Chloe; the Diochares Gate, from which one could travel to the demes that hosted the Thesmophoriai and to the sanctuary of Artemis at Brauron.19 Stelai construction would be resumed in the second half of the fifth century BC, and variations with respect to the Archaic stelai were to be significant.20

In this brief review of how funerary spaces were configured with clear representations of social class, age group and gender, one specific aspect merits more detailed attention: the use of different types of vessels (whether cinerary vases or grave markers) for men and women. This matter has been thoroughly studied by John Boardman, who analyses the evidence from the Geometric to the Classical periods.21 As indicated above, in the Protogeometric age, male cinerary urns were already differentiated from the female urns in shape: the former were neck-handled amphoras and the latter were belly-handled amphoras. While some have tried to explain this distribution as a possible anthropomorphization of the vessels, Boardman’s suggestion is more attractive and is based on the social use of these items: the neck amphora was used primarily for storing wine or oil; the belly amphora, like the hydria, was used to transport water. The association of wine–men, water–women is easily acceptable. To this we would add that this distinction is maintained in the Geometric period, and the krater – always associated with wine – is incorporated in the male graves. Boardman’s study also examines the figured representations on both types of pottery, and the data point in the same direction: scenes of prothesis (the corpse laid out) and ekphora (funeral procession) on kraters and neck amphoras are of men, and on belly amphoras they are of women.

After the seventh century BC, where the symbolic distinction between male and female graves was lost – more precisely, only adult males received formal burial – the sixth century BC resumes the former gender differentiation, and we have proof of this in a new type of pottery, a lustral vase called a loutrophoros, appearing at the end of the century.22 The association of the amphora with men and the hydria with women is again reflected in these new pottery pieces: in the loutrophoroi that portray funeral scenes, we find that male funerals are associated with amphora-loutrophoroi, and female funerals with hydria-loutrophoroi. The loutrophoroi become increasingly stylized and any practical use is abandoned; no longer having a specific lustral function, they are now used only for grave marking. This ‘uselessness’ for practical purposes is absolute in the marble loutrophoroi or figured loutrophoroi on stelai, by the late fifth and fourth centuries BC. Within the apparent continuity from the Geometric to the Classical period, there is a clear change from its origin as a strictly practical item, to the purely decorative sophistication of the Classical period. As Boardman concludes, while one cannot attribute all the connotations perceived in the Classical Age to funerary vessels of the Protogeometric, it is true that gender differentiation had already begun at that time.

Before concluding this section, it would be pertinent to note the problems that can be posed by symbolic codes based on gender distinctions. Although they are very useful and should be taken into account when analysing the archaeological material, they should be interpreted with caution. In the previous section, I discussed the objects deposited as grave-goods in the tombs. It is often assumed that these are related to the deceased and not to the family members who deposited them as offerings, but where an analysis of the bones does not provide sufficient evidence, attributing a tomb to a woman or a man on the basis of the grave-goods is unwise. There is widespread consensus that the presence of a sword indicates a man’s grave, but does a fibula necessarily indicate a woman’s grave? What if a woman had placed her favourite fibula in her husband’s grave? In fact, fibulae are found in both men’s and women’s graves. What archaeological studies have shown is that until successive sumptuary laws led to grave-goods being replaced by other forms of ostentation such as the stelai and statues known as korai and kouroi, the existence of women’s graves containing very varied offerings of great value, generally richer than those of men, remained a constant, especially in the ninth century BC.23

I will now focus in greater detail on the funerary monuments themselves, the semata, or ways of marking a grave location. According to excavations carried out in cemeteries from the Geometric era and early Archaic period in Athens, Anavyssos, Eleusis and Thera, the funerary monument at that time consisted of one simple, undressed stone, between 50 and 100 centimetres high; some of these have been found in situ on top of both inhumation and cremation graves. In the case of Attica, the most ancient ones are from the tenth century BC, and, logically, have no inscription at all; later markers at Thera, c. 700 BC, usually have the name of the dead engraved vertically from one end of the stone to the other.24

Archaeological findings agree with literary data in reporting the widespread custom of erecting these blocks of stone over the tomb. With time, the stone gave way to the column (κίων) and to the stele (στήλη).25 The most widespread burial monument of the entire Greek world, a stele can go so far as to take the shape of a small building with a figured representation of the deceased, even including background scenes with other additional figures. But the stelai of the Archaic age are relatively simple, and their decoration and evolution has been amply studied by Gisela M.A. Richter in what has become a classic work on the topic.26

The stele is the most common element, but not the only possible offshoot from the earlier uninscribed markers. Also appearing in the Archaic age are statues of the deceased, either korai, standing maidens who are clothed, or kouroi, standing male youths who are nude.27 From c. 600 BC we have the Dipylon kouros, of which only the head and right hand are preserved. This was a luxury that only the wealthiest families could afford: notable examples, which I will discuss later, include the statue of Phrasikleia and the kouros Kroisos. The kouros, votive or funerary, is an aristocratic youth,28 eternally young and eternally handsome, not exemplifying any kind of homoerotic appeal, but male aristocratic excellence, arete.29 The korai, though they may have the same votive and funerary functions, are found in greater variety. Since they are clothed, there is the distinction between wearing a peplos or chiton, in addition to slight changes from one region to another. As of today, the monument to Phrasikleia is our only example of both kore and funerary inscription surviving together, and while the kouroi are more plentiful, the Kroisos kouros found at Anavyssos is also the only funerary example with an existing inscription. For this reason, I will pay special attention to both of these examples in the following chapter.

In this review of Greek funerary art, we must not overlook one highly important detail: the primitive stone erected over the tombs was a non-iconic element (a simple ‘sign’, σῆμα, a term used later to refer to the tombs); by contrast, bas-reliefs and statues present an image that portrays the deceased, though not in a realistic sense. This significant change, from a non-iconic to an iconic funerary element, takes place in the sixth century BC, the time of the aristocratic poleis. About this same time, we find another equally important novelty: a change in the placement of the funerary monument. It now occupies a more visible position, no longer necessarily atop the tumulus, but preferably along the road. Consequently, archaeologists sometimes find tumuli that include several graves, and somewhere nearby a funerary statue whose specific grave we cannot identify, though it belongs to a single family group. The principal issue is that the sema becomes an element of ostentation, integrated into the funerary space of a group.30 Although the data is scarce, there have been attempts to trace a geography of the Archaic kouroi of Attica, and it seems that they are distributed along the road that goes out from Athens and crosses the Hymettus, continuing as far as Sounion, a route that has only been identified at a few points: Myrrhinoutta (Μυρρινοῦττα, present-day Vourva), Myrrhinous (Μυρρινοῦς, present-day Merenda), Prospalta (Πρόσπαλτα, northwest of Kalyvia), Kephale (Κεφαλή, east of modern Keratea). These population centres, for the most part, belong to the coastal trittyes of their corresponding tribe, according to Cleisthenes’s reform, where a large presence of aristocratic groups is documented. In Athens itself, the geographic distribution that has been reconstructed seems to give preference to the coast, from Piraeus toward the east, toward the port of Archaic Athens, Phalerum.31

Kouroi and korai emphasize the youth of the deceased, but above all they indicate social status. Kouroi do not show variations according to age: pre-ephebic is not differentiated from ephebic and the absence of a beard is adopted as characteristic, accentuating the tragic nature of the mors inmatura. There is no conflict with the evidence that the kind of age represented is not ‘physiologically determined’, but rather a ‘historical category’ of age: as in the epic kouros, the statue portrays the age of a socially and physically powerful figure, youth as the privilege of a warrior.32 In the korai, as we will see in Phrasikleia, the period of life represented in the statue is that of parthenos. This moment of plenitude, and nothing else, is what the representation seeks to portray.

With regard to the stelai, there is some variation from the Archaic to the Classical Age. To begin, I will summarize the different types that are found in the Archaic Age.33 The most common image on the Attic stelai is that of a nude young man, again a kouros; he may carry a spear or be characterized as an athlete. Older men are also found, represented with beards, such as the hook-nosed boxer that we see in one of the stelai recovered from the Themistoclean wall.34 Thucydides, speaking of the construction of the Athens city walls, says that it was done quickly, in a make-do fashion, using all kinds of stones that had not even been dressed to fit together. In fact, he states that they made use of πολλαί τε στῆλαι ἀπὸ σημάτων καὶ λίθοι εἰργασμένοι, ‘many stelai from the tombs, and sculpted stones’.35 Also famous is the stele of the warrior Aristion, clothed and armed, the work of Aristocles, found in Velanideza.36 Another of the better-known stelai is the so-called Stele of the Alcmaeonids, or Brother and Sister Stele, dedicated to two siblings, a male youth and a little girl, the only Archaic Attic stele that is wholly preserved, although today it is divided between two museums.37

According to Boardman, Attic stelai tend to distinguish three life-stage archetypes in the Greek man: the nude, athletic youth (characterized by the javelin, disc and aryballos); warrior (with sword and armour); and older man (with cane and sometimes accompanied by a dog).

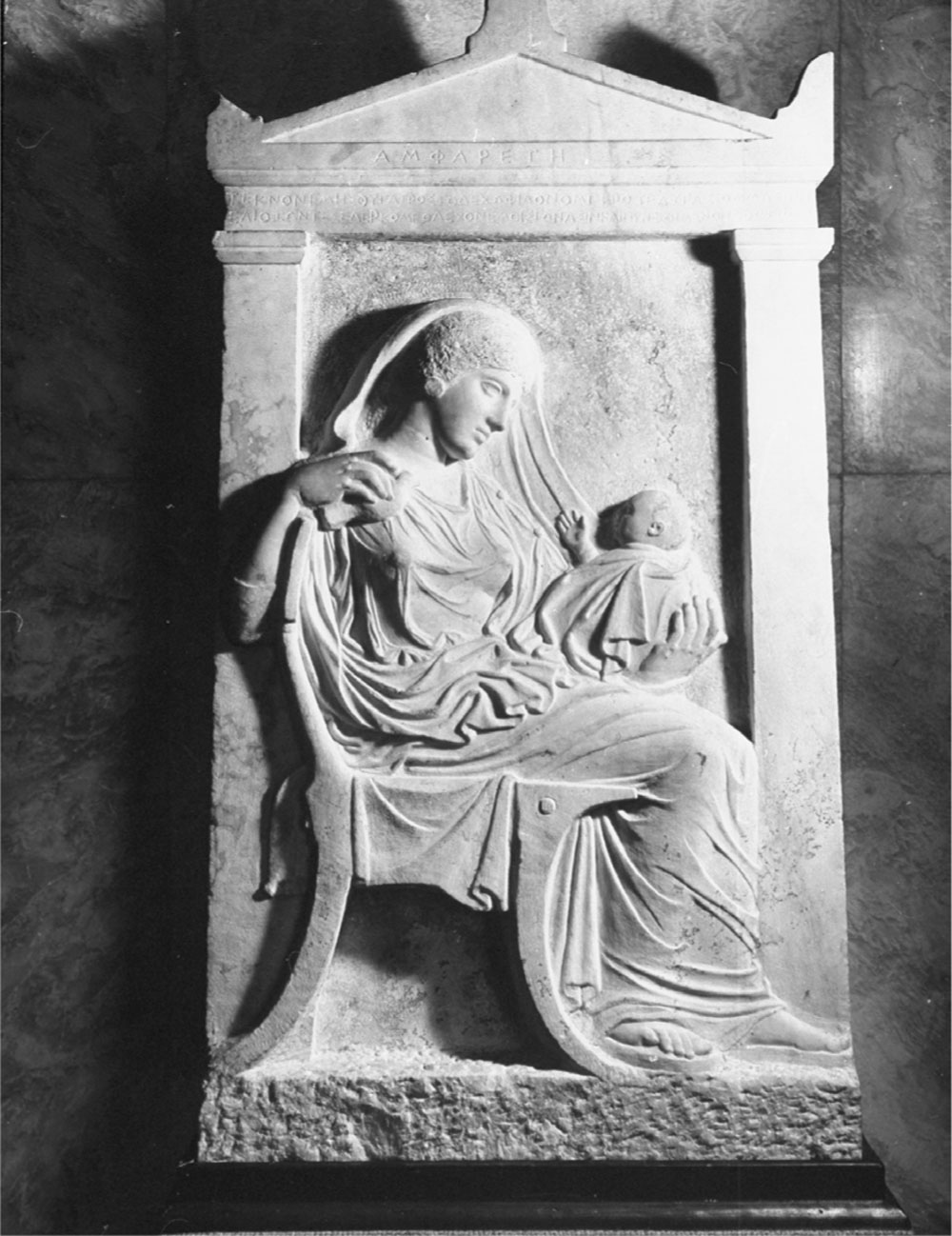

In all these cases the stelai are tall and narrow, but in the late Archaic period, other, wider stelai appear, such as one that in all likelihood represents a mother and child.38 Only fragments of this stele have survived – all that can be distinguished is part of the mother’s face and her left hand holding the child’s head. It has no precedents in the Archaic stelai of Attica, but it does show continuity in the Classical age, in the famous Ampharete stele, iconographically similar, but, thanks to the surviving epigram, we know that it actually represents a grandmother with her grandchild.39

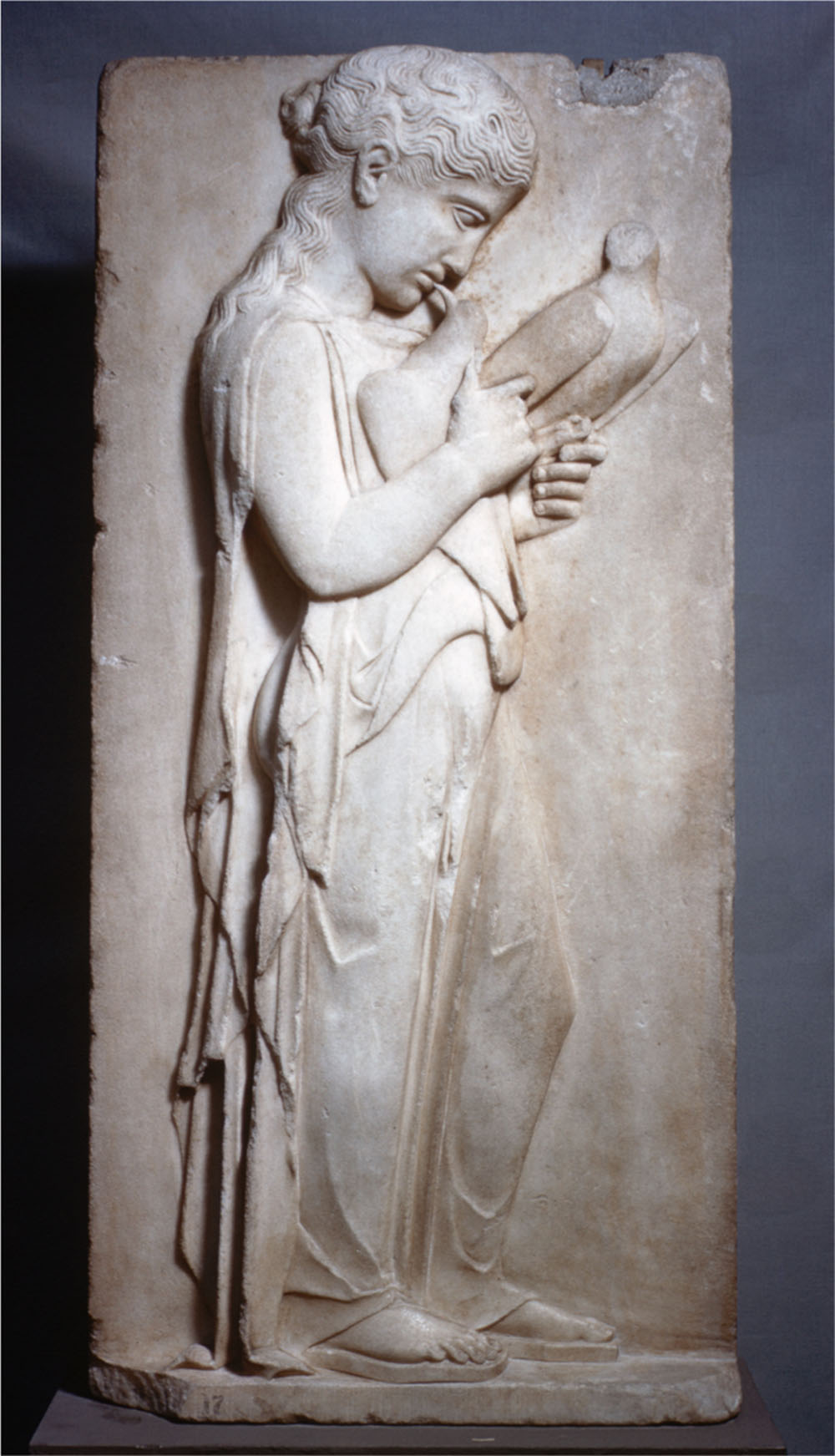

The erection of elaborate stelai in Attica ceases in the early fifth century BC and does not resume until c. 430 BC. However, construction continues in the rest of Greece, and new types appear:40 in addition to characterization by life stage, professions appear, for example, a lyre player,41 and women of different ages are represented, such as the young girl in the Giustiniani stele,42 probably from Paros, or the little girl with a pair of doves in her hands, from the same island.43 Another example of the splendour of funerary art in Paros is the stele of a mother, surrounded by three children and two youths that look on her with reverence.44 Also from the first half of the fifth century BC is the famous stele from Thessaly, showing an image of two young girls with flowers.45

Around 440–430 BC, stelai construction in Attica is resumed, and all authors concur in noting similarities between some of these stelai and certain images in the Parthenon frieze. During this period, hundreds of artisans had been working on the Acropolis in the enormous reconstruction project undertaken under Pericles; many of these artisans were also available for other artistic work such as the elaborate stelai that we speak of. There is now more variation among the stelai, and indications of age and family relationships appear: young athlete, older man with cane, woman with spinning wheel, man and wife, mother and child, etc. By contrast, there are very few individual representations of warriors, perhaps because the war dead are now honoured with state memorials. But above all, in the Classical stelai, it is interesting to note that greater attention is given to representing life stages. In the case of men, there is more than the old Homeric division kouroi/gerontes, and different life stages are articulated with the different male roles (childhood, ephebic status, adulthood/warrior stage, old age); in the case of women, the kore status continues to be quite present, with later stages now added (married woman, woman dying in childbirth, mother, old age),46 and occasional indications of profession, though examples are few.47

There has been a clear change: from the Archaic funerary statues (kouroi and korai), whose primary function was celebration of the aristocratic, to the stelai of the Classical age, reflecting a new organization of the city.

This review of the funerary landscape (especially in Attica, where most of our evidence is from) would be incomplete without noting the imprint left by certain laws and legislators who felt the need to regulate the rituals of bidding farewell to the dead.

The oldest funerary laws are attributed to Solon. Although the evidence is late, there is enough agreement to indicate a reliable tradition, or at least, the fact that already from the fourth century BC ‘Solon’s laws’ meant ‘traditional laws’. One of these ancient sources, although far from Solon’s time, is Plutarch,48 who attributes to Solon the prohibitions of speaking ill of the dead, of sacrificing an ox on the graves, and banning women from attending strangers’ funerals and weeping excessively, beating and cutting themselves. Plutarch is also the only one who historically contextualizes Solon’s laws. According to this author, when Solon had not yet been appointed archon, the Athenians sought aid from Epimenides of Knossos, due to his fame as a sage.49 A bloody feud had followed when Megacles’ supporters assassinated the supporters of Cylon, despite their having fled for refuge to the temple of the goddess at the acropolis, and now the city was divided and in need of purification. Apparently, the reforms proposed by Epimenides, who for example limited the lamentation of women at gravesites (καὶ τὸ σκληρὸν ἀφελὼν καὶ τὸ βαρβαρικόν, ᾧ συνείχοντο πρότερον αἱ πλεῖσται γυναῖκες, ‘elimination of the harshness and savagery that formerly characterized the behaviour of most women’),50 were inspiration for the measures later adopted by Solon.51

As for the funerary monuments, which interest us more directly, it seems that Solon’s legislation had no effect, and that the Athenians gave no thought to the size of these monuments or the expense involved. We have already seen above how the changes in funerary monuments over the course of the sixth century BC do not reflect any restraint in expense or splendour, quite the opposite. Solon’s laws, in principle, are not verifiable through archaeology, since they seem to address primarily the anthropological aspects of the funeral ceremony.52 Hence, although we generally speak of ‘sumptuary laws’ when referring to funerary legislation, this idea must be reconsidered in its relation to the laws of Solon. The idea that the old laws attributed to Solon limited excessive outlay for funerary ceremonies must have appeared no earlier than the late fourth century BC, and was adopted by Demetrius of Phalerum, Cicero and Plutarch, our sources on Solon’s laws.

Then what was the function of the laws promoted by this wise Athenian legislator? New interpretations suggest that anthropological aspects were the main thrust of these laws, including that they actually regulated relations between the living and the dead.53 These two are dangerously close in funerary ceremonies, and proximity to the corpse, a source of pollution or miasma, required that measures be taken. The women, responsible for washing and preparing the corpse, were more exposed to the contamination than men,54 and the desire to reduce miasma exposure would justify some of these laws that are attributed to Solon: men and women were to walk separately during the ekphora55 and this must take place before sunrise. Limitations on grave offerings can also be interpreted as the desire to separate definitively the dead from the living: it is one thing to place objects in the tomb that belonged to the deceased in life (swords, bronze fibulae, jewels, etc.) – they serve to illustrate the wealth of the oikos and to represent the status of the deceased. However, quite another are the offerings, oil and wine burned with the corpse or buried in the grave, the sacrifices or any other type of grave cult, practices that belong to another category and imply a relationship or exchange between the living and the dead. This is precisely the relationship that the legislation intended to break off.56 In this respect, we can recall that offering repositories (Opferrinnen) disappeared over the sixth century BC, having been linked possibly to the celebration of funerary banquets and in short, with a cult of the dead.

By contrast, other aspects of funerary regulation – that lamentations could only be sung at home, not at the graveside, even the celebrated prohibition of speaking ill of the dead – had more of a political basis: to avoid any incitement to vengeance or confrontation between families. Still, agreement with this functional interpretation of Solonian funerary legislation does not keep us from recognizing its intent to put a curb on the laments of women, or in the words of Ana Iriarte, ‘the power of incitement to revenge that the ancients perceived in the extremely emotional female lamentation’.57 While I can accept the idea that Solonian legislation has a basis in concerns of the era about miasma and purification, I cannot fully share in the conclusion that the main focus of the ancient laws was not women, but rather the fear of contamination from the dead, considering how closely the Greeks themselves associated women with miasma, and on another level, women’s lamentation with vengeance.

There is evidence of the determination with which many city-states, not only Athens, attempted to intervene through law in funeral rite practices. Although the testimonies are scarce, it is probable that between the Archaic and Classical periods, such laws in many cities were intended not to impose particular practices based on religious considerations, but to maintain a balance that was threatened by the ostentation of the aristocratic groups. In other words, although these so-called sumptuary laws put a stop to wasteful excess, in reality, this was merely a side effect of their essentially political nature, at least in the beginning. In the case of Athens, the restrictions imposed by funerary legislation were systematically flouted at public funerals: in civic celebrations for the war dead, the prothesis took place in a public space, whereas Solon decreed that this should take place inside the house; the duration of the public prothesis was two or three days compared to one day for a private one. According to Thucydides’ narrative, everyone could give the offerings they wished to their dead at state funerals, whereas Solonian law placed restrictions on such offerings. The institutionalization of public funerals clearly formed part of a process whereby the city-state placed limits on rivalries between different social groups, promoting homonoia and converting solidarity among family groups into solidarity among citizens.58

In contrast to Solon’s laws, later funerary laws did have an anti-sumptuary nature. Thus, between Solon’s archonship (594 BC) and the laws of Demetrius of Phalerum (317/6 BC), there must have been some regulation to reduce excess in Athenian memorials, although all we have are a few imprecise comments from Cicero,59 who alludes to certain post aliquanto reforms, ‘some time after’ the Solonian reforms. The change we speak of took place some time between the sixth and fifth centuries BC. Some authors relate the sumptuary rules to the laws of Cleisthenes, while others attribute them to Peisistratus, again based on Plutarch, who affirmed that Peisistratus preserved most of Solon’s laws.60

Be that as it may, whether a consequence of restrictive legislation or not, stelai production declined around 500 BC, as we have seen, to the point of almost disappearing. Later, beginning in 440 BC, we observe a splendid resurgence in stelai construction in Attica, to be interrupted only by Demetrius of Phalerum in the late fourth century BC, the person who put a curb on this extravagance: stelai in the form of small buildings, marble vases and statues gave way to modest columns, whose height was regulated by law, and to simple stelai.61

While the exact scope of funerary legislation is not easy to determine from the artistic evolution of the funerary monuments, there is undeniably a clear separation that can be established between monuments from the Archaic Age, especially the kouroi and korai in the sixth century BC, and the Attic stelai of the Classical period, from the middle of the fifth century BC until 317 BC. I will maintain this distinction throughout this study. Additionally, apart from funerary legislation, there are other causes that explain both the practical disappearance of stelai at the beginning of the fifth century BC, and their resurgence beginning c. 440 BC. In the former case, one can allege the state monopoly on public funerals; in the latter, the new availability of sculptors and artisans who had worked on the reconstruction of the acropolis.