Among the memorials that form the basis of our study, it is quite rare for dedicants to be friends of the deceased, and not his or her closest family members. Nonetheless, philia has also left its mark on the epitaphs of Archaic and Classical Greece. The texts that I will analyse in this chapter belong to the sixth and fifth centuries BC and are not continued in the metrical epitaphs of the fourth century BC,1 when an apparently wider variety may actually hide greater conventionalism, at least in the relationships observed between the memorials’ protagonists. It is the desire to devote a few pages to a subject I consider very interesting but which has received much less attention, namely the information that these memorials provide about the existence of deep ties of friendship between men, but also and especially between women, that has led me to interrupt the chronological order of this book and step back in this chapter to the end of the Archaic period.

In the first part of this chapter I will analyse the epitaph that a woman, Euthylla, dedicated to her friend Biote. In the second part I examine a beautiful stele of Mnesitheus that was discovered not long ago in Boeotia, dating from the late sixth century BC. Preserved intact with its inscription, this stele was erected by the young man’s lover. In the case of Biote’s epitaph, we will see that the vocabulary used (philotes φιλότης, hetaira ἑταῖρα, piste πιστή) seems to be chosen especially to fit with David Konstan’s description of friendship, drawn from a careful review of the applicable Greek lexicon: ‘Taken together, the terminological complex constituted by hetairos and the markers philos and pistos embraces the essential elements associated with friendship: a select relationship between non-kin grounded in mutual affection (“dearness”) and loyalty or trust’.2 For this reason precisely I find the Biote epitaph of special interest, given that examples of friendship between women are noticeably absent from studies on this topic. In young Mnesitheus’ funerary epigram it is easier to contextualize the type of relationship expressed; as far back as the mythical example of Achilles and Patroclus, the philia relationship between men, with varying degrees of eroticism, has been well known.3

On the 4th of last January (1892) a dealer in antiquities in Athens brought me a fragment of Pentelic marble bearing a metrical sepulchral inscription. He said that it was found near the Hagia Trias church, i.e., in the Ceramicus.4

Thus William Carey Poland begins the first published study on this late fifth-century BC epitaph, to which we now turn our attention. He had bought the marble fragment with the inscription, studied it, and being convinced that it was authentic, delivered it to the National Museum of Athens. It is currently catalogued and may be examined at the Athens Epigraphical Museum.5 Poland presents a very precise, hand-drawn representation of this stele in his article. The text of the epitaph follows:

πιστῆς ἡδείας τε χάρι|ν φιλότητος ἑταίρα|

Εὔθυλλα στήλην τήνδ᾿ἐ|πέθηκε τάφωι|

σῶι, Βιότη· μνήμηγ γὰρ |ἀεὶ δακρυτὸν ἔχοσα|

ἡλικίας τῆς σῆς κλαί|ει ἀποφθιμένης.6 |

For your faithful and sweet love, your friend

Euthylla has raised this stele over your grave,

Biote: with remembrance always filled with tears,

she weeps for your lost youth.

This epigram is special for many reasons, but I will begin by recalling the terms in which Poland described it, more than one hundred years ago. He refers first to the deceased and to the dedicant: ‘The monument before us is a private grave-stone of the more modest class erected by a woman named Euthylla in honour of a young friend named Biote. That she was young we are justified in inferring from ἡλικίας ἀποφθιμένης. The word ἑταίρα is used here simply to designate an intimate friend and companion, in the same earlier and nobler sense in which it was used by Sappho.’7 Next, the author offers the following two fragments as examples of this use by Sappho of Lesbos, reproduced here as in the Eva-Maria Voigt edition:

Λάτω καὶ Νιόβα μάλα μὲν φίλαι ἦσαν ἔταιραι (Fr. 142)

Leto and Niobe were very dear friends

τάδε νῦν ἐταίραις

ταὶς ἔμαις †τέρπνα †κάλως ἀείσω (Fr. 160)

now for my friends

I will sing these beautiful † … †

With female forms used in both appearances of friends, the context of the epigram is clearly identified, namely, the quite unusual case of a woman dedicating an epitaph to another woman outside of her family. However, further below we will consider the possibility that this may also be the case in other funerary stelai where the text is not preserved.

In the first verse there is another very interesting element that Poland does not mention: philotes (φιλότης). The term is a complex one, the kind of term that is part of the vocabulary of the culture, and as such difficult to translate. Before attempting a hypothesis about what it might mean here, we look for general instruction to the pages of Pierre Chantraine’s etymological dictionary, and to Émile Benveniste’s work on the vocabulary of Indo-European institutions. The former indicates that the meaning of philotes is ‘friendship’ or ‘affection’, sentiments based on ties of hospitality or camaraderie, often involving the existence of a specific community. He adds that the term also means, since the time of Homer, ‘sexual union’.8 Émile Benveniste insists on the reciprocity that is implied: ‘La philótēs apparaît comme une “amitié” de type bien défini, qui lie et qui comporte des engagements réciproques, avec serments et sacrifices.’9

This is the only appearance of the word philotes in funerary epigraphy (at least in the corpus of metrical epitaphs published by Hansen); it thus warrants some reflection about its meaning. Let us begin with the assumption that no translation is entirely free of interpretation: one Spanish translation is based on the mistaken idea that Biote is a man’s name,10 and includes this epitaph under a section entitled ‘conjugal love’, where the term philotes becomes ‘love’.11 By contrast, taking both names to be female, as in fact they are, we find the translations ‘friendship’, in Poland, and ‘amitié’, in a study by Calame, to which I will return later.12 But even this reassuring translation is accompanied by further explanations: while the ancient philosophers had words only for friendship between men, even modern interpreters show some resistance to friendship between women. Poland notes the strangeness of someone outside the family dedicating the epitaph to Biote, and he poses the hypothesis that she may be a female slave who was living in Athens, far from her family. He does not exclude the option (although relegating it to a note) that she may be a hetaira, in the sense of a courtesan, although the meaning of hetaira (ἑταίρα) in this poem would still be that of ‘friend’, the author maintains.13

According to Calame, not only Biote but also Euthylla should be recognized precisely as hetaira-courtesans: ‘La philia offre néanmoins un terrain où peuvent se développer entre citoyens et courtisanes, voire entre courtisanes elles-mêmes, des relations de fidélité réciproque’. Regarding this epitaph in particular, he states that ‘une “compagne” (hetaira) consacre à une femme disparue dans la fleur de l’âge une stèle funéraire en témoignage d’une relation d’amour (philotês)’ – amour that, as we indicated, later becomes amitié – ‘fondée sur fidelité et tendresse (pistê, h ê deia)’.14 The same internal inconsistency, caused by the desire to translate philotes as ‘love’ and yet not apply it to a feeling shared between women, can also be found in Poland’s work, which concludes with these words: ‘The little stone fell and was buried for centuries. The love – translated in the epigram as friendship – that created it lives on forever’.

Leaving philotes for the time being in its love–friendship ambiguity, we return to hetaira. There is a recurring tendency to understand hetaira as courtesan, with little room given to its sense of female friend or companion. As we have seen, this reading affects the interpretations of this epitaph, as a possibility in Poland, and almost a certainty in Calame. Clearly, the term is a female version of the masculine hetairos, and has the meaning of ‘companion, friend’ in addition to the Attic-Ionic meaning of ‘courtesan’. It should also be remembered that the term is semantically related to etes (ἔτης), another form for ‘friend’, which emphasizes that the companions are of the same age and social class. It should be easy, then, to distinguish the use of one meaning or the other based on the context: for example, in Sappho’s verses mentioned above, we understand that Leto and Niobe are hetairai in the first sense of the word. And the same should be true of this epitaph, where feelings of symmetry and reciprocity are expressed through both philotes and hetaira, and their close friendship is also spoken of as being faithful, piste (πιστή) and sweet, hedeia (ἡδεία). Did not Claude Calame himself state, at the beginning of his essay, that ‘c’est d’abord par sa douceur que l’on perçoit dans la poésie archaïque grecque la force de l’amour’?15

Affection, friendship, love. One of these sentiments, or all three, led Euthylla to raise a stele to honour her friend Biote. The negligible presence of the expression of these emotions between women in the texts is comparable to the scarcity of literature composed by ancient Greek women. However, if we consider it in relative terms, we find it is not so infrequent after all: leaving aside the verses of Sappho, so controversial and belonging to another era, we have the poetry of Erinna, from the fourth century BC, who remembers her friend Baukis in fragments of The Distaff (ἐμὰν ἁδεῖαν ἑταίραν, ‘my sweet friend’16) and mourns for her in a pair of epigrams of questionable attribution.17 At the end of the first epigram, we read: μοι ἁ συνεταιρὶς / Ἤρινν᾿ ἐν τύμβῳ γράμμ᾿ ἐχάραξε τόδε, ‘my companion Erinna engraved these letters on my tomb’.

It does not seem particularly unusual that friends would take part in mourning a deceased youth, whether a boy18 or a maiden.19 Returning to Poland, who discovered this stele, we find an apt comparison of the Biote epitaph with the epitaph that follows:

Ἀνθεμίδος τόδε σῆμα· κύκλωι στεφα|νοῦσ‹ι›ν ‹ἑ›ταῖροι

μνημείων ἀρετῆς | οὕνεκα καὶ φιλίας.20

This tomb is of Anthemis. Her companions place crowns around it

in remembrance of her excellence and friendship.

This epitaph was seen on a late fifth-century BC marble stele decorated with a painting; found in Piraeus, and since lost, our knowledge of it is based only on what we have been told by those who saw it. The old descriptions say that two women were represented on the stele: the name Herophile is inscribed on the left, above one of the paintings, and the name Anthemis on the right, above the other. We infer from the text that Anthemis died young, and although we do not know her relationship to Herophile (friend, sister, mother, etc.), the Clairmont hypothesis is quite probable,21 suggesting that Herophile is named as pars pro toto of her companions, of the hetairoi who place crowns on her grave, as we read in the epigram. Curiously, Calame also associates these two epitaphs, as does Poland, and once again his interpretation is that the grave belongs to a courtesan: ‘Tout porte à croire qu’Anthémis, hétaïre, était parvenue à s’insérer dans les relations de confiance réciproque fondant l’hétairie qu’elle fréquentait.’22

Returning to the Biote epitaph, all the elements of the first verse, whether hetaira (ἑταῖρα) that we have just discussed, or philotes (φιλότης), discussed earlier, underscore a relationship of reciprocity and loyalty, further emphasized by the adjective piste (πιστή), ‘faithful’. It has already been noted that neither pistos (πιστός) nor any of its derivatives appear in the Iliad or the Odyssey in relation to women (with the possible exception of Odyssey XI 456, in a verse that is considered to be interpolated, in order to affirm that women cannot be trusted: ἐπεὶ οὐκέτι πιστὰ γυναιξίν). In Homer, the expression pistos hetairos (πιστὸς ἑταῖρος), ‘faithful friend’, is reserved for male friendship, indicating a very specific type of relationship and personal feeling that goes beyond that of battlefield camaraderie (hetaireia).23 In Homeric poetry we find clear examples of the importance of such ties, always between men, and the variety of possible overtones. Thus, aside from the possibly erotic nature of the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus, the latter’s fundamental role is that of reliable counsellor to Achilles, the same role that Nestor plays in relation to Agamemnon, or Polydamas to Hector.24

The importance of this quality, of being pistos, trustworthy, is seen in an epitaph from the fourth century BC where the name of the deceased appears out of meter;25 however, the inscription proudly proclaims that he has won the nickname of Faithful:

(i) [τὄνο]![]() α μὲν τὀμὸν καὶ ἐμ ô πατρὸς ἥδε ἀγορεύ[ει] |

α μὲν τὀμὸν καὶ ἐμ ô πατρὸς ἥδε ἀγορεύ[ει] |

[στή]λη καὶ πάτραν· πιστῶν δὲ ἔργων ἕνεκα ἔσχο[ν] |

[Πίσ]τος ἐπωνυμίαν, οὗ σπάνις ἀνδρὶ τυχεῖν.

(ii) Πραξῖνος | Τερεία | Αἰγινήτης.26

This stele bespeaks my name, that of my father,

and my homeland. On account of my trustworthy deeds I have won

the nickname of Faithful, rarely attained by a man.

Praxinos, son of Tereias, from Aigina.

In the Biote epigram, the adjective is applied to philotes, and offers a testimony of friendship and faithfulness between women, of particular interest in a social framework that entirely overlooks the topic of such relationships.

I want to insist that the translations ‘friend’ and ‘hetera’ (courtesan) for the term hetaira are both perfectly acceptable. But, in specific instances, both meanings are not possible simultaneously. If we consider that the epitaph is the preferred vehicle for celebrating the virtues of the deceased, and that, at least in this era, women’s professions were seldom mentioned therein (except for some cases of nursemaids and priestesses), it is very unlikely (if not simply unbelievable) that a woman would be remembered and praised by another as a ‘courtesan’. This reasoning excludes Claude Calame’s interpretation. As for Poland’s apparently naïve interpretation, alluding to the ‘noble’ sense of the word hetaira in Sappho, I consider it neither ingenuous nor misguided. The poetry of Sappho has been subject to very controversial interpretations over the centuries, constituting quite a thorny chapter in the history of Greek literature, impossible to summarize here. But if I must express my opinion (although tentative), I would lean towards Poland’s interpretation, supporting it with some words from the famous essay ‘Against Interpretation’, by Susan Sontag. Allow me to explain.

In the late twentieth century, there were a number of voices within American criticism that reacted strongly against the image of a Sappho Schoolmistress, a view from the nineteenth century that pictured Sappho leading a circle of girls whom she instructed in music and song and to whom she addressed her poems. This reaction was in turn answered by other scholars of such calibre as Bruno Gentili. One of the more controversial points is that, according to the new interpretation (ascribed especially, but not exclusively, to gender studies), the homoeroticism perceived in Sappho’s poems was not addressed to girls, nor did it have any religious, ritual or pedagogical value. Instead, it addressed the poet’s peers and its meaning was fully erotic. The details of this controversy and its proponents are perfectly reflected in an article by Bruno Gentili and Carmine Catenacci,27 whereby I excuse myself from delving at length into an already familiar topic.

There are serious arguments on both sides, but, in my opinion, the problem is distorted because the Sappho texts have long suffered the abuse of interpretation. Here is where I recall the words of Sontag: ‘Interpretation thus presupposes a discrepancy between the clear meaning of the text and the demands of (later) readers. It seeks to resolve that discrepancy. The situation is that for some reason a text has become unacceptable; yet it cannot be discarded. Interpretation is a radical strategy for conserving an old text, which is thought too precious to repudiate, by revamping it. The interpreter, without actually erasing or rewriting the text, is altering it. But he can’t admit to doing this. He claims to be only making it intelligible, by disclosing its true meaning.’28 It is evident that the poems of Sappho reveal strong feelings between women, expressed perhaps for the first time, or at least, for the first time in preserved texts. At the same time, the morally and ideologically charged nature of many translations and interpretations of Sappho’s poetry is undeniable.

The question is complex; in order to focus on the epitaph at hand, I will limit myself to two concerns. First, both Sappho’s poetry and this funerary epigram, each in its own context, are in some sense exceptions. There are no other remains of Archaic Greek poetry from female authors with which to compare the preserved fragments from Sappho. And, as far as I know, we have no other epitaph where one woman has erected a memorial to another, without there being any family tie. This lack of context has led readers to look elsewhere for models. To explain Sappho’s poetry, and specifically the relationship that connected her to the women addressed in her verses, many different types of comparisons have been made (comparisons to Alcaeus and his hetairia; to Socrates and his disciples; even, defying the anachronism, to ‘young ladies’ finishing schools’). In the case of the epigram dedicated to Biote, its uniqueness has led either to misinterpretation (as in the case mentioned, interpreting Biote to be a man’s name, and therefore, a husband mourned by his wife) or to associating it with the world of courtesans, apparently more familiar than that of female friendship.

The second matter that I wish to bring out has to do directly with the first: the literary tradition beginning with Homer has delved deeply into the topic of friendship between men. It is not just an anecdote that Montaigne, author of the most admirable pages on friendship, would expressly state that the female sex is incapable of this type of relationship.29 Of course the situation has changed, and Mointaigne no longer represents the communis opinio on the topic, but the study of friendship between women in the ancient world remains unexplored, due to a lack of sources.

With these premises, my opinion about the epitaph dedicated to Biote can be summarized as follows: the context rules out the idea of courtesans, and also excludes any family relationship between the dedicant and the deceased; the lexicon used belongs to the semantic field of friendship sentiments, and probably, of love; the degree of intimacy between Biote and Euthylla is difficult to determine, and if we seek a comparison with the verses of Sappho, it ought to be in the sense of expanding our knowledge about relationships and friendship ties between women in the ancient Greek world. To use our relatively modern categories of heterosexuality and homosexuality does not help at all in understanding the poetry of Sappho or that of her male contemporaries. But if we add this epitaph to the surviving Sapphic poems that speak to her hetairai, it may help us gain a somewhat better understanding of friendship/love between ancient Greeks, and more specifically, of friendship/love between women.

To conclude my discussion of this memorial, I shall turn to iconographic representations, and in particular, to an interesting image that may also be of a funerary nature, although this is not completely certain. I refer to the stele of Pharsalus.30

This particular image reminds me of the study by Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz, regarding the representation of female homoeroticism in Attic ceramics.31 One of this author’s conclusions is that neither pederasty nor heterosexuality can help us in deciphering possible expressions of female homoeroticism; the latter, besides being much less explicit, shares neither the age asymmetry typical of pederastic courtship scenes, nor the asymmetry of power and/or violence commonly observed in representations of heterosexuality. Here we have an image that supports this conclusion and evokes the piste and hedeia philotes of the Biote epitaph.

Much has been written about this piece, and although naturally there is no single, unanimously accepted opinion, there is some consensus about its homoerotic nature.32 On the one hand, although it is an argument ex silentio, the fact that the two women are not shaking hands with the dexiosis gesture would indicate that they are not linked by family ties.33 On the other hand, the iconography is clearly erotic, with the presence of lotus flowers that the two women seem to be exchanging or showing to each other, and the ‘hands up and down gesture’34 that is associated with courtship images. Also fully applicable to this image are the following words written about other images with a clearly sexual content, such as the famous Macron cup: ‘l’échange des regards se double de gestes d’offrande et de réception de cadeaux (bourse, couronne, fleur) ainsi que de contacts mutuels’.35

Figure 5.1 The stele of Pharsalus, c. 470–460 BC, Thessaly. Louvre Museum: 701 © Bridgeman Images.

While it may be true that there are few images and texts acknowledging the existence of philotes-based relations between women, it also seems true that the biased interpretations of such evidence often contribute to the sense of ‘strangeness’, through distortions of trying to fit them into the patterns of pederasty or heterosexuality, or because the term hetaira itself, in its ancient and noble sense, does not have the evocative power of the courtesan.

As a final remark on the Biote stele, I recall one of the many noteworthy facts that William Carey Poland pointed out in 1892 in his article on the recently discovered piece – perhaps partly to justify so much attention given to a simple stone: the epitaph has also provided us with a proper name that was heretofore unknown: Euthylla, the dedicant of the monument. However, a later discovery brings a Euthylla who, according to the editors of the text, would be the same Euthylla who dedicated the memorial we have just studied. This Pentelic marble stele, dating to the fourth century BC, was discovered on 5 May 1938 in the Agora:

[Ε]ὔθυλλ[α ---- ----] / θυγάτη[ρ---- ----] / ![]() ευκον[οέως γυνή]36

ευκον[οέως γυνή]36

If the Euthylla who appears here is indeed the same one who dedicated the stele to Biote, the fact that on her own stele she is mentioned as gyne (γυνή), ‘wife’, reminds us once again that arguing a possible erotic link between Euthylla and Biote does not in the least imply talking about an exclusive homosexuality or using contemporary categories to explain the sexual practices of the ancient Greeks.37

A fortunate archaeological discovery from 1992 restored to us a stele whose image and accompanying inscription are both perfectly preserved, and where once again the dedicant is not related to the deceased person through family ties.

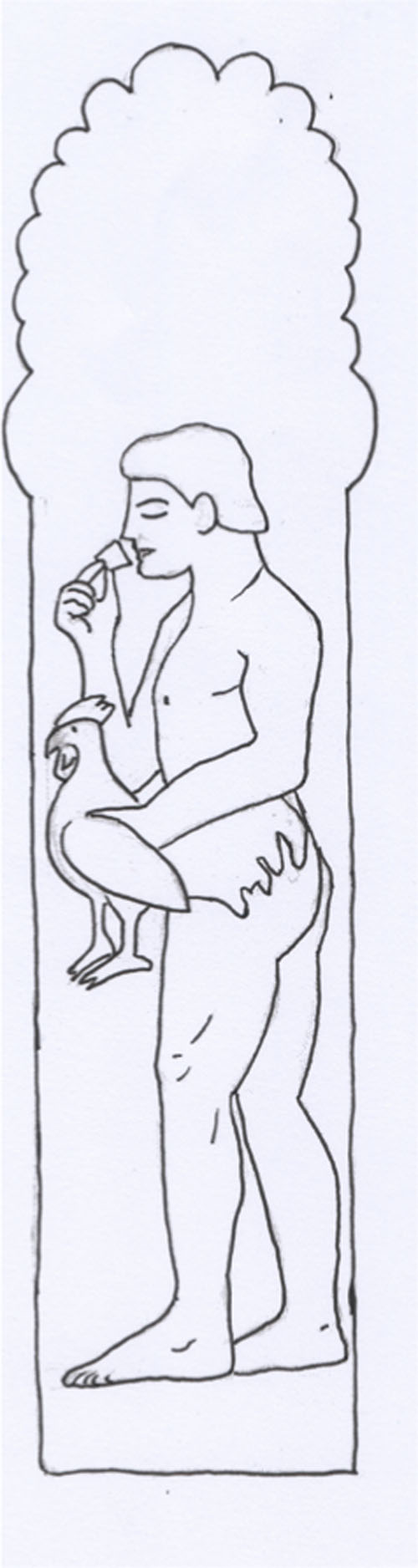

Found in the Acraephia necropolis in Boeotia and dated between 520 and 510 BC,38 this stele represents a nude boy, in profile and turned towards the left, holding a rooster in his left hand while raising a flower to his nose with his right. Between his left leg and the edge of the stele, an elegiac distich in the Archaic alphabet of Boeotia can be read. At the foot of the stele, the artist’s signature, Philergos. It is made of Hymettus marble and is the work of an Attic workshop that was heavily under influence from Ionia.39 The text, inscribed in stoichedon,40 is as follows:

Μνασιθεί![]() μν

μν![]() μ’ εἰ

μ’ εἰ![]() ὶ ἐπ’ ὀδ

ὶ ἐπ’ ὀδ![]() ι καλόν· ἀλ‹λ›ὰ μ’ ἔθ

ι καλόν· ἀλ‹λ›ὰ μ’ ἔθ![]() κεν

κεν

Πύ‹ρ›ριχος ἀρχαί![]() ς ἀντὶ φιλ

ς ἀντὶ φιλ![]() μοσύν

μοσύν![]() ς.

ς.

Φιλ![]() ργος ἐποί

ργος ἐποί![]() σεν.41

σεν.41

I am the lovely memorial of Mnesitheus, beside the road. I was placed by

Pyrrhichos, as a reward for everlasting love.

Philergos42 made me.

The text of the stele is framed in the setting of a philia (φιλία) relationship between two men, a type of relationship that often occurred within the aristocratic world where one of the two was often younger.43 Quite remarkable is the use of the term philemosyne (φιλημοσύνη), very infrequent and entirely equivalent to philia and philotes.44 This term only appears in one of the funerary inscriptions forming the corpus established by Hansen, CEG 32, which I translated in Chapter 3; namely, the epitaph dedicated by a father to his two sons. It reads as follows: σ![]() μα τόδε : Κύλον : παίδοι‹ν›| ἐπέθεκε{ν} : θανό‹ν›τοι-: / μ‹ν›

μα τόδε : Κύλον : παίδοι‹ν›| ἐπέθεκε{ν} : θανό‹ν›τοι-: / μ‹ν›![]() μα| φιλεμοσύνες : … This tomb was raised by Cylon for his two dead sons, / a memorial of affection … Recently, Emanuele Dettori has written about philemosyne.45 In relation to CEG 32, he maintains that since the purpose of the inscriptions was to give tribute to whatever the deceased had left behind on Earth worthy of remembrance, in this case the father wanted to immortalize the philemosyne of his sons.46 Although this is obviously true, I do not believe it follows – as Dettori claims – that one must therefore reject Angeliki Andreiomenou’s interpretation of Mnesitheus’ memorial, according to which the term philemosyne refers to a reciprocal feeling between Mnesitheus and Pyrrhichos.47 According to Dettori, rather than commemorating an affective relationship between the two, the dedicant Pyrrhichos’ intention in raising the memorial was to express gratitude for the philemosyne of the deceased, Mnesitheus. He bases this reading on his interpretation of CEG 32. In my opinion, this line of reasoning is not entirely logical. To begin with, he takes what was merely a hypothesis to be true, namely that in CEG 32, the dedicant Cylon is celebrating his sons’ love in a unidirectional manner: his sons’ love towards him. Based on this premise, he infers that the dedicant of Mnesitheus’ stele is commemorating the philemosyne of the deceased and not a reciprocal feeling between the dedicant and the young man who died. I do not see the need to render these options exclusive: quite the contrary. There is no doubt that one celebrates philemosyne, the affection that the sons showed their father in life and the other, Mnesitheus’ affection for Pyrrhichos, but I believe it is equally unquestionable that in both cases, the affective relationship and the sentiment immortalized on the memorial was mutual. Otherwise, the very existence of the funerary monument would be inexplicable.

μα| φιλεμοσύνες : … This tomb was raised by Cylon for his two dead sons, / a memorial of affection … Recently, Emanuele Dettori has written about philemosyne.45 In relation to CEG 32, he maintains that since the purpose of the inscriptions was to give tribute to whatever the deceased had left behind on Earth worthy of remembrance, in this case the father wanted to immortalize the philemosyne of his sons.46 Although this is obviously true, I do not believe it follows – as Dettori claims – that one must therefore reject Angeliki Andreiomenou’s interpretation of Mnesitheus’ memorial, according to which the term philemosyne refers to a reciprocal feeling between Mnesitheus and Pyrrhichos.47 According to Dettori, rather than commemorating an affective relationship between the two, the dedicant Pyrrhichos’ intention in raising the memorial was to express gratitude for the philemosyne of the deceased, Mnesitheus. He bases this reading on his interpretation of CEG 32. In my opinion, this line of reasoning is not entirely logical. To begin with, he takes what was merely a hypothesis to be true, namely that in CEG 32, the dedicant Cylon is celebrating his sons’ love in a unidirectional manner: his sons’ love towards him. Based on this premise, he infers that the dedicant of Mnesitheus’ stele is commemorating the philemosyne of the deceased and not a reciprocal feeling between the dedicant and the young man who died. I do not see the need to render these options exclusive: quite the contrary. There is no doubt that one celebrates philemosyne, the affection that the sons showed their father in life and the other, Mnesitheus’ affection for Pyrrhichos, but I believe it is equally unquestionable that in both cases, the affective relationship and the sentiment immortalized on the memorial was mutual. Otherwise, the very existence of the funerary monument would be inexplicable.

Dettori insists that philemosyne is an individual feeling that does not imply the existence of a mutual relationship; however, neither does it exclude one, which would make no sense in this context and would render the memorials dedicated by Cylon and Pyrrhichos absurd. Even translating, as I have done, ἀρχαί![]() ς ἀντὶ φιλ

ς ἀντὶ φιλ![]() μοσύν

μοσύν![]() ς as ‘a reward for everlasting love’, in other words interpreting this funerary memorial as a tribute to Mnesitheus’ love for Pyrrhichos, it is obvious that the reciprocity of this feeling is evidenced by the very existence of the memorial.

ς as ‘a reward for everlasting love’, in other words interpreting this funerary memorial as a tribute to Mnesitheus’ love for Pyrrhichos, it is obvious that the reciprocity of this feeling is evidenced by the very existence of the memorial.

The idea that philemosyne is an individual feeling, an unreciprocated affection, also leads Dettori to focus on the differences rather than the similarities between the epigram dedicated to Mnesitheus and the next epigram, attributed to Simonides:

Σῆμα Θεόγνιδός εἰμι Σινωπέος, ᾧ μ’ ἐπέθηκεν

Γλαῦκος, ἑταιρείης ἀντὶ πολυχρονίου.48

I am the tomb of Theognis of Sinope, for whom

Glaukos placed me in recompense for a long friendship.

Where other authors have seen a clear parallel, Dettori in contrast suggests that in Simonides’ poem, Glaukos erects a monument as a reward for the friendship shown to him by Theognis and refers to her as ἑταιρείη (hetaireia), thus using a well-known term that indicates a clear mutual bond in the context of a political community. Such is not the case, he insists, of the stele that Pyrrhichos erected to reward Mnesitheus’ philemosyne towards him. For my part, I remain unconvinced by this argument: while I understand that philemosyne does not necessarily imply reciprocity, in contexts such as these, far from excluding reciprocity, philemosyne demands it.

As for the translation of archaies (ἀρχαίες), I would propose ‘everlasting’ rather than ‘old’, although I do not discard the opinion of Angeliki Andreiomenou, who discovered the memorial: given that at least one of the protagonists was young in age, the term should not be given its usual sense of ‘old’, ‘from long ago’, but rather a sense of ‘constant’, ‘tried and true’ or ‘deep’.49 As to the meaning of anti, I do not agree with the idea that in the funerary epigraphy it must always mean ‘in place of’ rather than ‘in return of’.50 What I specifically disagree with is the idea of exclusively and systematically opting for one of these two readings. In this particular case, I have elected to translate archaies anti philemosyne as ‘as a reward for everlasting love’, which does not mean negating, obviously, that the memorial is there, before our eyes, whereas we can no longer see the love that once existed between Mnesitheus and Pyrrhichos. The sensual memorial commemorating Mnesitheus is a reward for his everlasting love, and at the same time a proxy, still capable of moving us, for an emotion whose protagonists have vanished.

Regarding the stele itself, unlike what we have seen with the Biote inscription, the elegiac distich is accompanied by an image with very clear symbolism, leaving no doubt about an erotic interpretation of the memorial. To begin, there is the rooster as the main gift which the erastes presents to the eromenos: the rooster has been accepted by the eromenos (to use Attic terms) in the same way as, after his death, the monument has been accepted by the eromenos and, presumably, his family. In addition, the flower (a lotus), which appears in other funerary stelai, has sexual overtones here as well,51 as another erotic type of present.

While it is true that there are few burial monuments with inscriptions from erastai (ἐρασταί) to eromenoi (ἐρώμενοι) or vice versa, I believe we cannot consider them entirely exceptional, especially in the light of continuing new archaeological discoveries. It is a fact that the dedicant is usually a very close relative,52 but in this case, as in the Biote stele,53 the dedicant who raises a stele for a loved one has no family connection whatsoever.

Although the examples of homoerotic representations in funerary iconography are not plentiful, the Mnesitheus stele immediately reminds us of another interesting memorial,54 which regrettably lacks an inscription. This piece in marble was discovered in 1988 in Ialysos, Rhodes, and dated c. 470–460.55 The erastes and the eromenos are both shown, the latter is seen receiving a rooster, erotikon doron. A life-size youth (1.83 metres), turned to the right, is represented giving a rooster to a young boy, who turns towards him in a very similar position to that of Mnesitheus, represented on a much smaller scale, emphasizing dependency. Both figures are nude, and the younger one holds the present given him by the erastes in both hands, while turning to look at him. As we look upon the youth, whom we can identify as the deceased, placing his gift in the hands of his eromenos, we notice not only the erotic symbolism but also a certain air of melancholy farewell, in tune with the funerary nature of the stele.56

The prosperity of the aristocratic families on Rhodes, hence their patronage, must have had much to do with this type of artistic creation, undoubtedly contemporaneous with other manifestations exalting the island’s nobility, such as Pindar’s Olympian 7, commissioned by Diagoras.57

Thus, we would not hesitate to claim that dedicants who appear on the stelai and have no family connection are linked to the deceased by bonds of friendship.58 The Biote epitaph from the Classical age, and the Mnesitheus epitaph in Archaic Boeotia, confirm that philia can also leave its immortal mark in stone.

We cannot conclude this chapter without mentioning an intriguing epigram that offers new, clear evidence of the existence of homoerotic relationships between males, and the possibility that such ties could become sufficient motivation for one of them to dedicate a memorial at the death of the other. This inscription is considered votive by some editors and funerary by others, the latter opinion now prevailing.59 In this Attic text from the late sixth century BC, contemporary with the Mnesitheus stele, the funerary monument itself addresses us, in hexameters:

(i) ἐνθάδ’ ἀνὲρ ὄμοσε[ν κα]|τὰ h όρκια παιδὸς ἐρα[σ]θὶς

νείκεα συνμείσχι[ν] (sic) πόλεμόν θ’άμα δα|κρυόεντα.

Γναθίο,| τ![]() σφυχὲ (sic) ὄλετ’ ἐ[ν δαΐ], | h ιερός εἰμι60|

σφυχὲ (sic) ὄλετ’ ἐ[ν δαΐ], | h ιερός εἰμι60|

τ![]() h εροιάδο.

h εροιάδο.

(ii) [Γνά]![]()

![]()

![]() αἰεὶ σπευδε[-]61

αἰεὶ σπευδε[-]61

Here a man committed himself with vows for the love of a boy

to engage in battles and in tearful war.

To Gnathios, who lost his life in battle, I am consecrated,

to the son of Heroiades.62

Gnathios, always –

The aristocratic origin of the deceased is indicated by the appearance of σπευδε[-] in the second part of the inscription, perhaps referring to σπουδαῖος, a term associated with the aristocratic sphere, and preferred by Aristotle when referring to the ‘noble’.63

In any event, Kaibel already affirmed – against earlier opinions – that rusticorum autem hominum carmen uix est, and he based that suspicion on the epitaph’s possible allusion to an elegy by Anacreon:

οὐ φιλέω, ὃς κρητῆρι παρὰ πλέωι οἰνοποτάζων

νείκεα καὶ πόλεμον δακρυόεντα λέγει,

ἀλλ᾿ ὅστις Μουσέων τε καὶ ἀγλαὰ δῶρ᾿ Ἀφροδίτης

συμμίσγων ἐρατῆς μνῄσκεται εὐφροσύνης.

I like not him, who, when he quaffs wine over a full bowl, talks of strifes and tearful war, but him who mixes the glorious gifts of the Muses and Aphrodite and recalls the good times which he loves.64

The Homeric expression polemon dakryoenta (πόλεμον δακρυόεντα), ‘tearful war’, is found in these lines, and was also seen in the Gnathios epitaph. It appears just this once in the corpus of metrical funerary inscriptions.

The few references to this epigram that I have found, most of them quite old, understand it as an erotic relationship situated around the Persian Wars: haec enim scripsit belli Persarum fere aetate homo quidam Atheniensis in memoriam iuuenis amati, ‘this was written, more or less around the time of the Persian Wars, by an Athenian man in memory of his young beloved’.65 Logically, we are to suppose that it was the eromenos who raised this memorial.66