There is an unwritten rule, nearly always respected in the stelai and funerary epigrams, of not mentioning the cause of death. This fact was already noted by Nicole Loraux, when studying death in childbirth: ‘Sur les reliefs funéraires des cimetières athéniens, le mort est, on le sait, représenté dans ce qui fut sa vie; aucune allusion n’est faite à la mort qui fut la sienne, à deux exceptions près: mort d’un soldat, mort d’une accouchée.’1 In earlier pages, I have referred more than once to the death of a warrior, speaking of young men fallen in battle, such as Kroisos or Tetichos. Now I turn to the memorials of women who died in childbirth, and also to the funerary monuments of those lost at sea, as these constitute exceptions to the rule stated above. Not only are there Archaic epitaphs that mention this type of death, there is also iconographic representation on the stelai. This is the case of the splendid Democlides stele which I speak of later.

To be precise, it is not the moment of death that is represented,2 but rather the cause of death. Childbirth and the sea were terrible enemies in the everyday life of Greek men and women; over the course of their lives, women faced childbirth, and the sea endangered both men and women, though predominantly men. It is no coincidence that when Burkert speaks of votive offerings as an extremely common religious practice, a fundamental strategy for facing the future, he uses the specific example of ‘the dangers of a sea voyage, the incalculable risks of birth and child rearing, and the recurrent sufferings of individual illness’.3 If the biggest danger for the dominant class was war, as Burkert indicates, the typical dangers faced by the average man and woman were others. The corpus of funerary inscriptions only confirms the data from this other corpus of votive offerings.

Although I do not deny the obvious association between death at war and death in childbirth, highlighted by Nicole Loraux and later authors,4 I wish to suggest another comparison, also marked by gender, this time between women’s death in childbirth, and the death of men, almost exclusively, at sea. Like the other cases, death at sea constitutes a new exception to the rule against mentioning the causes of death in Attic stelai, whether in text or iconography.

The existence of epitaphs dedicated to women who died in childbirth is inseparable from discussions concerning a passage in Plutarch’s Life of Lycurgus, worth mentioning here:

Lycurgus 27, 2: ἐπιγράψαι δὲ τοὔνομα θάψαντας οὐκ ἐξῆν τοῦ νεκροῦ, πλὴν ἀνδρὸς ἐν πολέμῳ καὶ γυναικὸς [τῶν] λεχοῦς ἀποθανόντων, when they buried them, it was not allowed to inscribe the name of the deceased over the grave, except for those who had died in war, if it were a man, or in childbirth, if it were a woman.

The trouble comes from the fact that this text, where Plutarch speaks of Spartan legislation, has been corrected in its most interesting point. The manuscripts offer the following reading: ἐπιγράψαι δὲ τοὔνομα θάψαντας οὐκ ἐξῆν τοῦ νεκροῦ, πλὴν ἀνδρὸς ἐν πολέμῳ καὶ γυναικὸς τῶν ἱερῶν ἀποθανόντων, ‘when they buried them, it was not allowed to inscribe the name of the deceased over the grave, except for a man who had died in war, or if it were a woman, one of the hiérai’.5 Why has the text been emended? The reading given by the manuscripts presented no grammatical problem, but the identity of the hierai was an enigma; even though publications throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth century maintained the unmodified text, Ziegler introduced the new text in the 1926 Teubner edition, attributing the emendation to Latte. Since then the correction has been widely adopted, if not unanimously. While the earlier reading of the manuscripts did not present any grammatical problem, neither does this emendation, and it has the advantage of fitting with our expectations about Spartan society: ‘c’est ainsi que des énigmes se remplissent de choses connues’.6

What information can epigraphy contribute on each of these readings? In support of the now prevailing interpretation, the one that corrects the Plutarchean text, four Lacedaemonian funerary inscriptions are offered, each dedicated to a woman who died in childbirth (λεχοῖ),7 in addition to a number of Laconian epitaphs referring to war dead (θανόντες ἐμ πολέμῳ).8 The question, then, is whether to accept this evidence to justify such a drastic intervention in a perfectly grammatical text, namely, to substitute ἱερῶν with λεχοῦς and reject τῶν,9 or whether, on the contrary, to consider that there may have been hierai in Laconia, and try to clarify what the meaning of this term was.

Richer, one of the scholars who rejects Latte’s emendation, argues in favour of this option in his study on funerals in Sparta.10 In his opinion, the Chaironeian is telling us that in Sparta, a rule attributed to Lycurgus allowed for graves of the war dead and of women belonging to the class of the hierai to not be anonymous. What was the meaning of this term, hierai? It must certainly indicate a very lofty quality, since it allowed a woman to attain honour equal to that of a man who died in battle, but the author goes no further than to suggest that this status has more to do with the religious than with the political.

It is important to note that we also have epigraphic evidence in favour of this alternative: there are inscriptions where the names of women are followed by hiera (ἱερά) or hiara (ἱαρά). This limited dossier is composed of five Lacedaemonian inscriptions11 – not Spartan, admittedly – and nothing is said of these women except that they have died. However, the Messenian dossier is more illustrative, and includes an important text about the mysteries celebrated in the city of Andania.12 While the authors admit that it is not possible to equate the Messenian and Lacedaemonian hierai, it seems unlikely that they were totally different from each other.13

One recent study that defends the manuscript reading takes one step further, posing the following question: if such a privilege (to inscribe the name of the deceased over the grave) was granted to men who had fallen in battle and to women who exercised a religious function, why is nothing said of the men who also exercised that function at the time of their death? In fact, men who acted as priests and who died in battle could attain greater honours than the hoplite, as is inferred from a passage by Herodotus regarding the battle of Plataea. Herodotus mentions that the Spartans fallen in Plataea were buried in three tumuli, one for the priests, another for the Lacedaemonians, and another for the helots. The problem, once again, is that this text has also been amended: Valckenaer, in 1700, replaced ‘priests’ (ἱρέας and ἱρέες, in 9.85.1 and 9.85.2) with eirenes (ἰρένας and ἰρένες, respectively), the young Spartan hoplites over the age of twenty.14

For my part, I prefer the policy that if no problems appear in the text, but we do not understand it, what we should do is try to understand it, not modify it.15 In order to break the impasse regarding Plutarch’s text on the legislation of Lycurgus, perhaps we should ask other types of questions, for example, what is the context of the Laconian inscriptions where hierai are mentioned? The five inscriptions that speak of hierai appear in three places: Geronthrae (Γερόνθραι), Teuthrone (Τευθρώνη) and Pyrrichos (Πύρριχος):

Geronthrae inscriptions:

IG V 1, 1127: [— — — — —][— —]![]()

![]() [— — — —]ο/ [— —]ης χαιρέτω. / Ἀγίεια χαῖρε ἱα[ρά]./ [— — χαῖ]ρε./ Ἀγίεια χαῖρε. / Νικοδαμία ἱα[ρὰ χαῖρε]./ [Καλλ]

[— — — —]ο/ [— —]ης χαιρέτω. / Ἀγίεια χαῖρε ἱα[ρά]./ [— — χαῖ]ρε./ Ἀγίεια χαῖρε. / Νικοδαμία ἱα[ρὰ χαῖρε]./ [Καλλ]![]() σθένης ἱερὸς χαῖρε. / Α[— —]/ Βιόδαμος χαῖρε.

σθένης ἱερὸς χαῖρε. / Α[— —]/ Βιόδαμος χαῖρε.

IG V 1, 1129: Σαλίσκα / ἱερά· χαῖρ![]() .

.

Three hierai (ἱεραί) and one hieros (ἱερός) are named. Geronthrae was known for its cult to Ares, from which women were excluded;16 but on the acropolis there was also a temple to Apollo, to whom these inscriptions would be related.17 Pausanias says nothing of Artemis, although this goddess is sometimes worshipped alongside Apollo. For example, an inscription c. third century BC refers to Apollo Hyperteleates along with Agrotera Kypharissia (Ἀγροτέρα Κυφαρισσία, IG V 1, 977), Agrotera being a well-known epithet of Artemis. Two inscriptions from the same Apollo fanum (sanctuary of Apollo Hyperteleates, Laconia) are preserved, one dedicated to a priestess (IG V 1, 1068 [— — Ἀφρο]δεισίου ἱέρια Ἀπόλλ[ωνος Ὑπερτελεάτ—]) and another to a priest (IG V 1, 1016 Σωτηριί[ω]ν Λακε(δαιμόνιος) ἱερεὺς Ἀπόλλωνος Ὑπερτελεάτου).

IG V 1, 1221: Ἀριστονίκα ἱερά, χαῖρε. Φιλάρ[ιν — — — —].

SEG 22.306: Πολυκράτια ἱαρὰ χαῖρε

Artemis Issoria was worshipped in Teuthrone, according to Pausanias.18 The goddess Artemis was invoked with the same epiclesis in Sparta in one of her sanctuaries that marks the borders of the civic territory.19 We must assume that these have to do with the same goddess and the same function.

IG V 1, 1283: Σοφιδοὶ / ἱαρὰ Σ![]() [— —] {ἱαρασ

[— —] {ἱαρασ![]() [μένα]?}.

[μένα]?}.

In Pyrrichos there was a temple to Artemis Astrateia, worshipped alongside Apollo Amazonius.20 The goddess, associated with Apollo, is invoked in the place where ‘the Amazons ended their expedition’, hence the name, according to Pausanias.21

There are numerous locations of Artemis cult in Sparta, and generally in Laconia, twenty-five according to a recent study.22 The literary and archaeological evidence in most of these locations points to a celebration associated with rites of passage, either for boys or girls – certainly one of the most well-known aspects of Artemis cult. But in regard to our topic, we also find remarkable the places where the goddess is presented as a huntress and in a defensive role, though fewer in number. These locations concur largely with the places where inscriptions mentioning hierai (and hieroi) are found: the above-mentioned locations of cults of Artemis Astrateia (Ἀστρατεία) in Pyrrichos, Artemis Issoria (Ἰσσωρία) in Teuthrone, and Artemis Agrotera Kypharissia (Ἀγροτέρα Κυφαρισσία), east of the river Asopus, to which we must add Artemis Ἰσσωρία and Artemis Ἀγροτέρα in Sparta. In the light of this evidence, might we associate the inscriptions with places where Artemis was worshipped in the role of defending territory, either alone or alongside Apollo, and where men and women performed some kind of religious function for which they were called hieroi and hierai, as appears in the epitaphs?

It is only a hypothesis, but it would allow us to respect Plutarch’s text, in addition to confirming the fact that, in Spartan society, their priests enjoyed higher privileges than did priests in other cities.

In any case, regardless of the reading adopted for Plutarch’s report about the Spartans, I believe we can assert that special importance was given to death in childbirth, as will be demonstrated in the metric epitaphs we are about to consider.

The war–childbirth association that underlies Plutarch’s report in the Life of Lycurgus, with all the nuances that I have already mentioned, can be justified with other arguments. First we have the etymology, since lochos (λόχος) is both ‘childbirth’ and ‘ambush’ (later, also ‘armed combat’),23 although much doubt has been cast on this etymological equality, with claims that they are simply homonyms.24 However, a link between the two concepts is also upheld by other terms such as ponos (πόνος), a name for the efforts of the warriors, for the work of heroes, but also for the pain and effort of childbirth.25 In defence of this interpretation, which may actually lean more towards its womanly usage, we can also cite the famous words of Medea:

[…] ὡς τρὶς ἂν παρ᾿ ἀσπίδα

στῆναι θέλοιμ᾿ ἂν μᾶλλον ἢ τεκεῖν ἅπαξ

… I would rather take my stand behind the shield three times than give birth only once26

In the epigraphic corpus that forms the basis of this study, we find minimal evidence of epitaphs for women who died in childbirth: only two epigrams, both from the fourth century BC, neither of them accompanied by an image. The dossier could be expanded somewhat if we also included the stelai that represent this motif, but for which we have no epitaph.27

The first piece of evidence is a marble stele with an inscription in elegiac distichs:

παῖδά τοι ἰφθίμαν Δαμαινέτου ἅδε Κρατίσταν, |

Ἀρχεμάχου δὲ φίλαν εὖνιν ἔδεκτο κόνις, |

ἅ ποθ’ ὑπ᾿ὠδίνων στονόεντι κατέφθιτο πότμωι, |

ὀρφανὸν ἐμ μεγάροις παῖδα λιποῦσα πόσει.28

The truly courageous daughter of Damainetos, Kratista,

beloved wife of Archemachos, has been received by this very dust,

She who one day perished in fateful throes of childbirth,

leaving an orphan son at home to her husband.

Despite being found in the Kerameikos, the epitaph of this stele is written in literary Doric, an intriguing fact that scholars have tried to explain with more or less ingenuity. Nicole Loraux suggests that the deceased is thus being singled out as a ‘Spartan of honour’, in line with the Plutarch passage already discussed. According to Kaibel, perhaps Damainetos was of Doric origin and had given his daughter in marriage to the Athenian Archemachos. In any case, as we often find in metrical epitaphs, its literary pretensions become clear in the use of such terms as the epic pote (πότε) in the third verse: we remember the epitaph of young Kroisos, victim of Ares, who died one day in battle. Loraux herself, whom we have just cited, has said as much: ‘le vocabulaire est celui de l’épopée, depuis le trépas gémissant (στονόεντι πότμωι) jusqu’au mégaron, et de l’expression du courage par la force (ἰφθίμαν: courageuse) à la désignation de l’épouse comme compagne de couche (εὖνιν), en passant par l’indétermination du πότε (un jour)’.29

The next epitaph with this argument, a stele with an inscription in elegiac distichs, reads thus:

(i) Κλεαγόρα Φιλέου Μελ[ιτέως γυνή].

(ii) εἰς φῶς παῖδ’ ἀνάγουσα βίου φάος ἤν[υσας αὐτή], |

Κλεαγόρα, πλείστης σωφροσύνης [μέτοχος], |

ὥστε γονεῦσιν πέ![]()

![]() ος ἀγήρατο

ος ἀγήρατο![]() [λίπες - -]·|

[λίπες - -]·|

ἐσθλῶν [¯ ˘ ˘ ¯ ¯ ˘ ˘ ¯ ˘ ˘ ¯]

(iii) Φιλέας | Φιλάγρου | Μελιτέυς30

(i) Kleagora, wife of Phileas of Melite

(ii) In bringing a child to the light of life, you put out the light of your own,

Kleagora, you who shared in the finest good judgement,

So that you have left your parents undying sorrow.

(iii) Phileas, son of Philagros of Melite.

To live is to be in the light. This text establishes an opposition between light and darkness that would become customary, especially in Hellenistic literary epitaphs, but in this case it has a two-fold value, as it also plays with the image of birth as coming into the light of life. The contrast between the light that shines on the new-born child and the light that faded from the mother as she gave birth is what renders this epitaph special, because of its very sophisticated use of the ‘light imagery’ common to other funerary epigrams.31

With so few examples to draw from, on this occasion I will also consider the metrical epitaphs from the third century BC, reproduced at least in part in a recent publication.32 There are only two, both from Thessaly, but they are worth some attention, particularly because of the lexicon that is used to refer to a woman who died in childbirth:

Λυπρὸν ἐφ’ Ἡδίστηι Μοῖραι τότε νῆμα ἀπ’ ἀτράκτων

κλῶσαν, ὅτε ὠδῖνος νύμφη ἀπηντίασεν·

σχετλίη· οὐ γὰρ ἔμελλε τὸ νήπιον ἀνκαλιεῖσθαι

μαστῶι τε ἀρδεύσειν χεῖλος ἑοῖο βρέφους·

ἓν γὰρ ἐσεῖδε φάος, καὶ ἀπήγαγεν εἰς ἕνα τύμβον

τοὺς δισσοὺς ἀκρίτως τοῖσδε μολοῦσα Τύχη.33

A painful thread for Hediste did the Moirai spin out from their spindles

when the young wife reached the throes of childbirth:

Wretched one! for she was not to hold her new-born child

nor nurse the lips of her new-born at her breast.

He saw the light of life one single day, and Fate has led them

both to a single grave, coming on the two with no distinction.

This funerary stele consists of two parts that were discovered during different archaeological excavations. The upper part is painted with a scene depicting a woman on her death bed after giving birth, surrounded by family and friends. The continuation of the painting on the lower part has been lost, but the metrical inscription translated above remains.34 The special consideration given to women who died in childbirth is also evident in this stele from Thessaly, which was described by Arvanitopoulos as a naiskos, suggesting that the deceased was honoured as a heroine.35 Although other authors do not agree that the form of the stele is that of a naiskos, they do agree that it is a special sculptural form used for stelai commemorating women who died in childbirth.36

Hediste is a young wife, a nymphe (νύμφη), a name that would perhaps also be appropriate for the protagonist of the next epitaph, which plays with the sense of this threshold situation:

Πουτάλα Πουταλεία κόρα,

Τιτυρεία γυνά.

Ὤλεο δὴ στυγερῶι θανάτωι προλιποῦσα τοκῆας

Πωτάλα, ἐγ γαστρὸς κυμοτόκοις ὀδύναις·

οὔτε γυνὴ πάμπαν κεκλημένη οὔτε τι κούρη.

πένθος πατρὶ λίπες μητρί τε τῆι μελέαι.

Ἑρμάου Χθονίου.37

Potala daughter of Potalus

wife of Tityrus.

Has succumbed to a terrible death, abandoning her parents,

Potala, in waves of labour pains from your womb:

you are called neither a complete woman nor a maiden.

You have left pain to your father and to your mother, crushed.

The epitaph opens with two lines, the first to identify the young woman as a daughter, with a mention of her father (a sense we have already seen with kore), the second line indicates her status as a married woman, the wife of a husband who is also mentioned by name. After the two elegiac distichs that form the epitaph itself, the memorial closes with an invocation to Hermes of the Underworld.

These two distichs refer to death in childbirth and make the intriguing affirmation that, as a consequence of that death, the young woman cannot be invoked in either manner that the epitaph itself has presented her: neither maiden nor wife. Setting aside the rhetorical play that may be involved in this statement,38 it is not an entirely trivial affirmation, and offers us another piece of information: the young woman had not yet had any other children. The woman was only a true gyne (γυνή) when she became a mother, and not from the fact of being married.

Another key term in this epitaph is the hapax kymotokos (κυμότοκος). It is evident that we are dealing with a metaphor; the question is to decide on its meaning. Literally, kymotokos means ‘that produces waves’, and it could thus refer to ‘les flots de sang qui auraient accompagné l’accouchement’.39 This hypothesis should not be discarded using the argument that the details of death could have been expressed more clearly, as is seen in later, Hellenistic epigrams. As we have been observing, it was not customary to elaborate on the causes and details of death; only later literary epitaphs develop further in this direction.40 The other option is to consider the term itself, kyma (κύμα), ‘wave’, as having the sense of ‘embryo’, a metaphorical origin whose use is perfectly documented: the young woman had died ‘dans les douleurs de l’enfantement du fruit que tu portais’.41

It is difficult to be certain, but the presence of waves at sea as a cause of death in the epitaphs of the shipwrecked might endorse the hypothesis that the author of this epigram chose this particular image, uniting one terrible death with another. And so we approach our next topic.

The nightmare of death at sea and the unburied victim was familiar to the Greeks from early on. We see it reflected in a ceramic piece from the late eighth century BC, found in Pithecusae (Ischia), a krater showing one of the earliest examples of Geometric art with figures.42 Of course, even the poetry of Homer and Hesiod speaks of terrible deaths at sea,43 but, we might say, with some restraint. In the ceramic piece from Pithecusae, the harsh consequences of the shipwreck are represented, the fears which epigrams of the Hellenistic period revel in, such as the body never recovered, fodder for the fish.44 The impossibility of burial is a recurring motif in these epitaphs. This is a break in the natural course of events, as in the earlier case of youths hindered from reaching the fulfilment of marriage. We find overlapping images, such as the young woman dead in childbirth, mentioned above, who can be called neither wife nor maiden (οὔτε γυνὴ πάμπαν κεκλημένη οὔτε τι κούρη), with that of an epitaph from the Palatine Anthology, where a young woman’s death at sea is the cause that her father cannot accompany her to her wedding, neither as a maiden nor as a cadaver (ὅς σε κομίζων / ἐς γάμον οὔτε κόρην ἤγαγεν οὔτε νέκυν),45 in a very explicit image associating death and marriage in Hades.

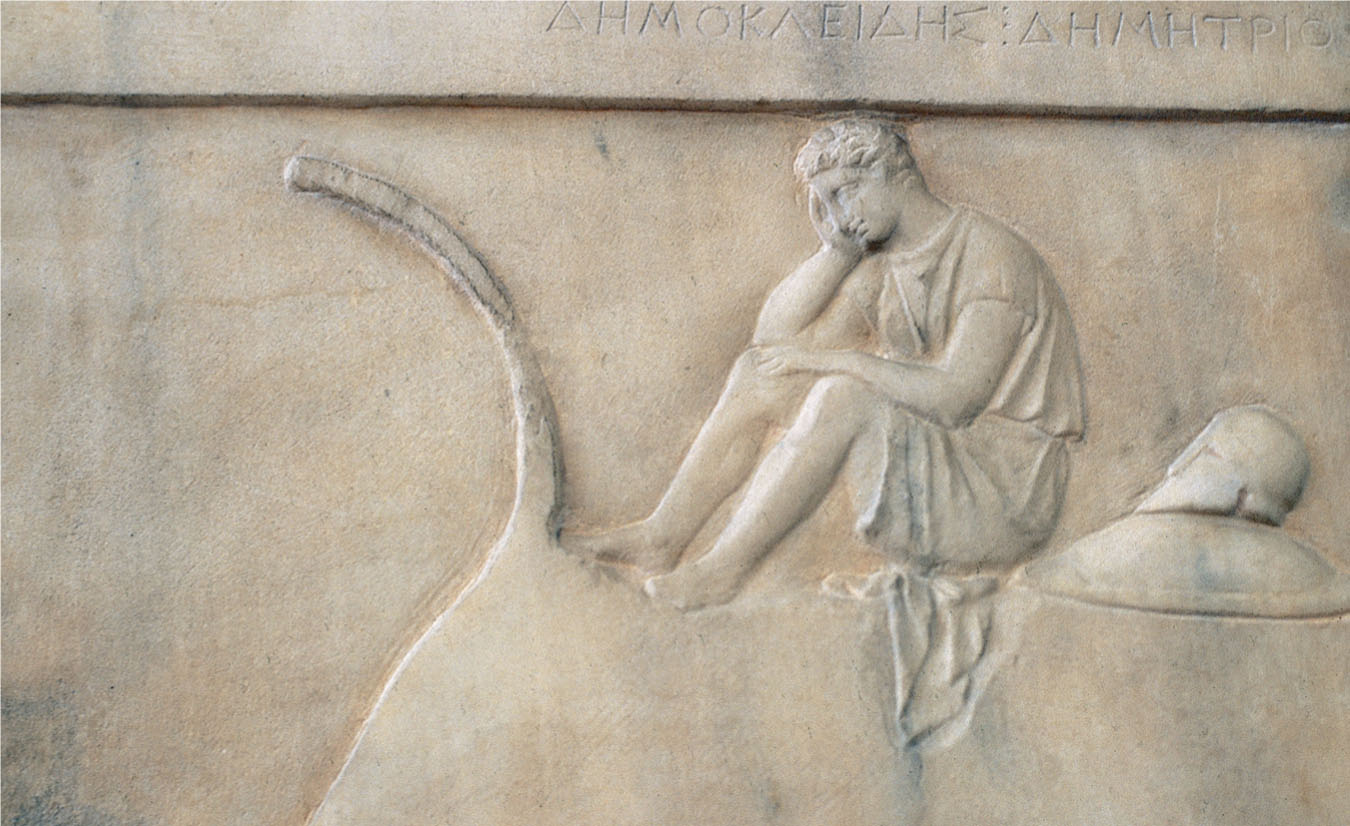

As I have stated, death at sea constitutes one of the rare cases where the type of death is indicated iconographically. In her classical study on Greek epigraphy, Margherita Guarducci points to the stele of Democlides as one of the most beautiful surviving examples. In the far upper right, a pensive young man is represented, seated on the bow of a ship.46 The rest of the stele is practically empty, emphasizing the loneliness of the victim in the immensity of the sea. In the epigraph, only the young man’s name and filiation are indicated: Δημοκλείδης Δημητρίō, ‘Democlides, son of Demetrius’.

Focusing on the metrical epitaphs, we find a few that are dedicated to shipwreck victims in both the Archaic and Classical periods. Later, in the Hellenistic era, this type of epigram develops further, becoming one of the most reproduced subtypes within the genre.

To Corinth, Corcyra and Sikinos, one of the Cyclades, belong three Archaic epitaphs composed for shipwreck victims. Each of them contains an explicit mention of death at sea through use of the term pontos (πόντος). The first of these, from the mid-seventh century BC, consists of a single hexameter inscribed in boustrophedon:

Δϝεινία τόδε [σᾶ|μα], τὸν ὄλεσε π|όντος ἀναι[δές]47

Tomb of Deinias, whom the insatiable sea destroyed.

The circumstances in which this memorial was found serve to remind us of the hazards which today’s evidence has managed to survive. Lilian H. Jeffery tells the story in an article dedicated to some of these Archaic epitaphs: ‘It is recorded that a Greek farmer, ploughing a field, turned up a limestone stele over a metre long, with a carved projection on top, a painted border round the sides of the main face, and an inscription cramped into the upper part. As there was apparently nothing on the long space beneath, the farmer broke off the top piece with the inscription and took it home, leaving the greater part of the shaft behind. Whether it really was blank, or whether there had once been some decoration on it, either painted or incised, must therefore remain unknown.’48

The name of Deinias, protagonist of the memorial, is found in the etymological dictionaries as a personal name derived from deinos (δεινός), ‘terrible’, an adjective related in turn to deido (δείδω), ‘to fear’.49 A terrible name for a terrible death, also reflected in the use of the verb ollymi (ὄλλυμι) – we have already had occasion to discuss its appropriateness for heroic death (recall the epitaph of Kroisos, h όν ποτ’ ἐνὶ προμάχοις ὄλεσε θ ô ρος Ἄρες). This brief hexametric epitaph, from the mid-seventh century BC, belongs to an era when the Homeric poems had already more or less reached their present form. Though not Homeric, it has what we might call ‘Homeric colour’. In the Iliad and the Odyssey, the sea is wide (εὐρύς), boundless (ἀπείριτος), wine-coloured (οἶνοψ), purple (ἰοειδής), unharvested (ἀτρύγετος); in the Odyssey, the stone of Sisyphus is called laas anaides (λᾶας ἀναιδής), the reckless, ruthless stone.50 In this epitaph, pontos anaides (πόντος ἀναιδές), ‘the insatiable sea’, my translation of preference, may also be the merciless sea, unrelenting as the stone of Sisyphus.

The next example, a public monument (the people made it), is from the end of the same century, and is composed of six hexameters that go around the tumulus in a single line, almost ten meters long. The shipwreck victim has received the honorific title of proxenos, granted to foreigners who had rendered some special favour to the city.51 His brother, having come from his homeland, joins the people in raising the memorial:

h υιοῦ Τλασίαϝο Μενεκράτεος τόδε σᾶμα

Οἰανθέος γενεάν, τόδε δ’ αὐτ ô ι δᾶμος ἐποίει.

![]() ς γὰρ πρόξενϝος δάμου φίλος· ἀλλ’ ἐνὶ πόντοι

ς γὰρ πρόξενϝος δάμου φίλος· ἀλλ’ ἐνὶ πόντοι

ὄλετο, δαμόσιον δὲ καϙὸν ῥο[v – v v - -].

Πραξιμένης δ’ αὐτ ô ι γ[αία]ς ἄπο πατρίδος ἐνθὸν

σὺν δάμ[ο]ι τόδε σᾶμα κασιγνέτοιο πονέθε.52

This is the tomb of Menekrates, son of Tlasias,

Oianthian of race, the people made this for him.

He was proxenos, a friend of the people, but at sea

he died, a public misfortune […]

Praximenes, having come from his homeland,

together with the people vigorously raised this tomb to his brother.

The memorial is a cenotaph, as expected in the case of shipwreck, and confirmed by excavations that did not find any remains under the tumulus.53 It has been noted that the emphasis on the work carried out to raise the memorial of this illustrious foreigner (the tumulus having a very Archaic appearance), might be a literary reference to Homeric funerals, where the warriors exerted themselves in the construction of a tumulus over the hero’s grave.54

Finally, our last example from the Archaic age is a marble stele raised in honour of a shipwreck victim by a family member who is identified with the unusual term of matrokasignetos (ματροκασίγνητος):

μνᾶμα νέωι {![]()

![]() } φθι

} φθι![]() [έ]|νωι

[έ]|νωι ![]()

![]()

![]() ικρα[τ]ί[δαι]| τόδ’ ἔθηκε|

ικρα[τ]ί[δαι]| τόδ’ ἔθηκε|

ματροκασί[γνητος]· | πόντ![]()

![]()

![]() ’ [αὐ]τ[όν] | μ’ἐκάλυφ

’ [αὐ]τ[όν] | μ’ἐκάλυφ![]()

![]()

![]() .55

.55

This memorial was placed for young Sosikratides, dead,

by his maternal uncle. As for me, the sea has hidden me.

The translations that I have been able to find for this epitaph, only three and all in English, are not unanimous in their interpretation. ματροκασίγνητος is translated as ‘brother’56 or ‘uterine brother’,57 in two of them; the third opts for ‘mother’s brother’,58 a possibility to which I am also inclined. It is true that the dictionaries offer the first of these two meanings as the only option for this term, in adherence to the authority of Aeschylus, who in verse 962 of The Eumenides, has the Erinyes address the Moirai as matrokasignetai (ματροκασιγνῆται), ‘sisters, daughters of the same mother’, something that all the translators are quick to explain in a note: the Moirai, like the Erinyes, are daughters of the Night. But mythical genealogies are tricky, and there are other versions: the Moirai, according to Hesiod, are daughters of Zeus and Themis (Theog. 901–4); the Erinyes, according to the same poet, were born from maimed Uranus’s drops of blood, gathered to the breast of Gaia.

Arguing the meaning of matrokasignetai in this passage from Aeschylus is not my intent here; the meaning of ‘sisters born from the same mother’ is probable and traditionally understood, but I do not believe one can entirely rule out that matrokasignetos (ματροκασίγνητος, fem. -ήτη) also means ‘brother/sister of the mother’, a strict parallel with patrokasignetos (πατροκασίγνητος, fem. -ήτη), ‘brother/sister of the father’. This use of patrokasignetos as ‘paternal uncle’ is observed in the Iliad, Odyssey and Theognis, and is thus noted in the dictionaries; by contrast, the only appearance of matrokasignetos, outside this epitaph, is found in the Aeschylus piece, which may account for the fact that my proposed reading has hardly been considered.59 In fact, the form ματροκασίγνητος is not reflected in the dictionaries; they only offer the feminine form *μητροκασιγνήτη as a conjecture, based on the cited Aeschylus passage. One good argument in favour of the reading ‘mother’s brother, maternal uncle’, is that matrokasignetos understood as ‘uterine brother’ would come into unjustifiable competition with the term adelphos (ἀδελφός), whose etymological meaning is precisely that, ‘born from the same womb’. In fact, the creation of this new term in Greek, adelphos, in order to express a close fraternal tie via the mother, should be understood alongside the meanings acquired by similar terms such as the ancient phrater (φρατήρ), referring to the members of a large family, joined not necessarily by blood ties, but rather by a religious connection, and the more recent kasignetos (κασίγνητος), meaning blood brother, but also cousin, and emphasizing the paternal connection. However, one must also remember that there is a specific name for maternal uncle in Greek: metros (μήτρως).60

In any case, as is typical with this type of evidence, we clearly have no more information or context that can lead us to a firm conclusion about this epitaph. I do find it interesting to take note of this term which does not appear elsewhere, and when interpreting its meaning, to remember the particular place and importance of the figure of mother’s brother in the set of family relations. The important role of the maternal uncle in the education and care of boys has been studied in detail by Jan N. Bremmer, with examples that extend from Homer to the discourses of Aeschines and Demosthenes in the fourth century BC;61 this epitaph from the fifth century BC could be added to the corpus of evidence supporting this thesis.

Having reached the Classical age, we continue to find metric epitaphs dedicated to shipwreck victims. The following epitaph, from Amorgos, comes to us from the first half of the fourth century BC,

Κλεομάνδρο τόδε σῆμα, τὸν ἐμ πόντωι κίχε μοῖρα, |

δακρυόεν δὲ πόλει πένθος ἔθηκε θανών.62

This is the tomb of Kleomandros, whom the Moira reached at sea

and whose death left the city in tearful lament.

Most of the available information for studying the Greek polis is information specifically about the polis of Athens. What about the c. 1499 other ancient Greek poleis? This is the question that Mogens H. Hansen asks, and in order to answer it, he turns to the rich corpus of inscriptions. Specifically, he cites this epitaph as an example of the identification between polis and citizens: in Arkesine on the island of Amorgos the whole polis mourns over a drowned citizen.63

The following epitaph belongs to the same period, formed by four elegiac distichs and found in Piraeus:

(i) Ξενόκλεια χρηστή.

(ii) ἠιθέους προλιποῦσα κόρας δισσὰς Ξενόκλεια|

Νικάρχου θυγάτηρ κεῖται ἀποφθιμένη, |

οἰκτρὰν Φοίνικος παιδὸς πενθ ô σα τελευτήν, |

ὃς θάνεν ὀκταέτης ποντίωι ἐν πελάγει. |

(iii) τίς θρήνων ἀδαὴς ὃς σὴν μοῖραν, Ξενόκλεια, |

οὐκ ἐ‹λ›εεῖ, δισσὰς ἣ προλιποῦσα κόρας|

ἠιθέους παιδὸς θνείσκεις πόθωι, ὃς τὸν ἄνοικτον|

τύμβον ἔχει δνοφερῶι κείμενος ἐμ πελάγει;64

(i) Xenokleia, a good woman

(ii) Leaving behind two unmarried daughters, Xenokleia,

daughter of Nicarchos, lies dead,

after having mourned the pitiful end of her son Phoinix,

who died at open sea at the age of eight.

(iii) Who is so ignorant of threnodies that he does not mourn your misfortune, Xenokleia,

who leaving behind two unmarried daughters

you die from the painful absence of a son possessed by an unmourned

grave, lying in the dark sea?

This case is not strictly the epitaph of a shipwreck victim. The epigram is dedicated to a mother, Xenokleia, who has died of pothos for a son who disappeared at sea. I have translated this as ‘painful absence’.65 The term pothos (πόθος), more literally ‘longing’, is placed in contrast to himeros (ἵμερος), especially in erotic language: the latter burns in the lover’s breast before the object of its desire; the former breaks one’s heart because of the absence of this object. One desire about to be satisfied, in contrast to a desire with no prospect, heartrending.66 Undoubtedly, the translation ‘painful absence’ is not entirely satisfactory, but I believe it is not entirely unfaithful to the context, namely, the feared misfortune of one lost at sea: the body never recovered, and the ‘unmourned grave’. With regard to the structure of this epigram, Marco Fantuzzi has conducted a detailed study of the taste for variation on a theme, of which this epitaph is a good example.67 Virtually the same information is given in (ii) and (iii), but there is a change in perspective: in (ii), the message is delivered in an impersonal voice that speaks of Xenokleia in the third person, announcing that she is buried there, whereas in (iii), an external mourner addresses the deceased in the second person and shows compassion for Xenokleia’s pain as a mother who has suffered the loss of a child at sea.68

In another epitaph, from the same time and place as the last, the protagonists are a father, a son and a daughter lost in the Aegean Sea, a more precise reference than the vague indication of ἐν πόντῳ, ‘at sea’, which we have seen so far:

(i) Κώμαρχος, | Ἀπολλόδωρος, | Σωσώ | Ἡρακλειῶται.

(ii) οὗ τὸ χ‹ρ›εὼν εἵμ‹α›ρται, ὅρα| τέλος ἡμέτερον νῦν·|

ἡμεῖς γὰρ τρεῖς ὄντε | [π]ατὴρ ὑὸς ‹θ›υγ‹ά›τηρ τε|

[θ]νήισκομεν Αἰγ‹α›ίου | κύμασι πλαζόμενοι.69

(i) Komarchos, Apollodoros and Soso, from Herakleia.

(ii) You, whose destiny is decided, look now at our own end.

We, being three, father, son and daughter,

have died when traveling the waves of the Aegean.

Finally, on a Macedonian stele from the fourth century BC, we read a brief, expressive epitaph:

(i) Δίφιλος | Διονυσίο | Καύνιος

(ii) Στρύμονος ἐν στόματι | ναυαγήσας ἔλιπον φῶς.70

(i) Diphilos of Kaunos, son of Dionysios

(ii) After being shipwrecked at the mouth of the Strymon, I abandoned the light of life.

This last verse, with the image of the victim who loses life and light at sea, serves to reinforce a certain literary relationship between these epitaphs and those of women who died in childbirth. While the contrast between light and darkness, and between sound and silence, are quite frequent in all kinds of epitaphs, here this opposition is even stronger, for other reasons. In the case of death in childbirth, there is the contrast between bringing to light a new life, and losing one’s own light of life, as we saw in Kleagora’s epitaph; in the epigrams dedicated to victims of shipwreck we find an insatiable sea that deprives its dead of burial, hiding them in its depths, and adopting a function of covering, kalyptein (καλύπτειν), that in the normal course of events is reserved for the earth.