5

In June 2004, St. Paul’s police department inaugurated a new chief. John Harrington succeeded William Finney, who was retiring after a dozen years in the top job.

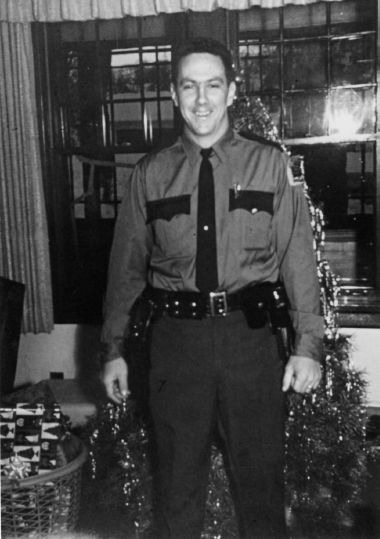

Harrington was a burly, physically intimidating, yet cerebral career cop who had grown up on Chicago’s South Side listening to his father, a Cook County deputy sheriff, and his dad’s cop friends exchange “war stories” on the family’s back porch. Much to his father’s displeasure, John had hung out for a while during his teenage years with a “younger chapter” of the Black Panthers. He had also listened intently as his father and his father’s friends discussed the fatal shootings of local Panther leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark during a blazing pre-dawn police raid on a Chicago apartment in December 1969. The account young John heard was dramatically at odds with the official version broadcast by the media. Contrary to those accounts—and as eventually confirmed by state and federal investigators—all but one of the nearly one hundred bullets that tore up the Panther apartment had been fired by the raiders, not by the occupants, which surely made the deaths of Hampton and Clark sound like cold-blooded murder. Harrington, nonetheless, wanted to be a cop, and, after pleasing his mother by earning a bachelor’s degree at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, found his way to the St. Paul department, which was then seeking minority-member recruits, and became a sworn officer in 1977.

Coming from Chicago, Harrington was amused by the differences between the two cities, especially as those differences pertained to race. He recalled with a laugh being driven down Selby Avenue by St. Paul relations and seeing what they referred to as the “ghetto” where “the black folks lived.” He said he looked at “all those substantial houses, with grass in the front yards—all the cars had their wheels, nobody had burglar bars on their windows—and I kept waiting to get to the ghetto. We got down to the Cathedral [at the eastern end of Selby], and I’m thinking, Hey, this is nicer than any place I’ve been living.” Even many of St. Paul’s so-called “militants” struck him, by Chicago standards, as “intellectual, academic, and pretty tame” for the era, “not exactly the type to throw a Molotov cocktail at a squad car.”

The racial divide was quantitatively less dangerous than it was in his hometown—and was somewhat improved over what it had been in St. Paul seven or eight years earlier. St. Paul’s police department, following the settlement of a federal anti-discrimination lawsuit, now included about thirty persons of color among its four hundred–plus sworn officers. The Sackett assassination, however, was still fresh in the minds of the city’s senior officers, whatever the pigmentation of their skin. While patrolling the neighborhood, an older partner would point out the relevant sites: “This is the house where Sackett got killed.” “That’s where we think they ditched the rifle.” Occasionally, Harrington rode with Glen Kothe, who would mention Sackett’s murder but didn’t offer any details. Making an arrest in a bar at Selby and Dale, Harrington said, “we’d been taught, ‘Go in, grab your prisoner, then drive as fast as you can out of the neighborhood.’ The explanation for that? ‘Sackett.’”

Now, in the summer of 2004, Harrington was briefed on the reopened Sackett case by Tom Dunaski. Harrington, like many in the department, viewed the pugnacious investigator as a force of nature who was impossible to put off, let alone ignore. Dunaski brought the new chief up to speed on the investigation and urged a “full-court press” to wrap up the case.

“Connie’s health is bad,” Dunaski told him. “Some of our witnesses’ health is bad. They’re old and they want to get this off their chest.”

Harrington, who had by now been part of the community for almost thirty years, believed Reed and Clark were legitimate suspects. “It wasn’t just the police department’s position,” he said later. “Folks who were credible to me—they were cops, they were black, they had grown up in the neighborhood—this is what they said was the truth.” Then there were the task force’s reports recounting the dozens of interviews with Reed’s and Clark’s associates, among them, most recently, Connie Trimble. “You could see things were moving,” Harrington recalled. “You felt that the case was building to a point where it was really going to happen.”

The chief had the support, moreover, of the mayor, Randy Kelly, and the city council, which, at the time, included Sackett’s power shift sergeant, Dan Bostrom, and Deborah Gilbreath Montgomery, the Summit-University kid who had grown up to be a nationally prominent civil rights activist and the department’s first female patrol officer and senior commander “who happened to be black.”

“We’ll find a way to get you what you need,” Harrington assured Dunaski at the end of their first meeting.

Somewhat to the investigators’ surprise, the hundred-thousand-dollar “Spotlight on Crime” reward, though publicized in the local media, had not yielded any significant information. Neither had Jeanette Sackett’s recent appearance in the paper and on TV asking the public’s help to bring “closure” for her family. Money from Dunaski’s task force budget was provided in small amounts to a few informants, but that was by no means unique to the Sackett investigation and, according to the investigators, was never a factor that would make or break the case. Almost everyone on the police and prosecution side would come to credit some combination of the investigators’ relentlessness and the eventual willingness of aging and conscience-driven witnesses to tell what they knew for their ultimate success.

The relentlessness was clearly part of Dunaski’s DNA and no doubt a component of Jane Mead’s and Scott Duff’s makeup as well. And while all three insisted that they would expend the same effort on any case—as the long, arduous Coppage and Gillum investigations seemed to verify—they also conceded that the victim at the heart of their current investigation made the case personal in a way that most cases would never be. The fact that the shooter seemed to be aiming at Sackett’s badge—whether he was or not, the symbolism of the bullet striking so close to the shield was potent—and the stories they picked up about young men firing at silhouettes of police officers in the ICYL basement, though never proved, couldn’t help but stoke the investigators’ emotions.

“I mean, who were these guys that they thought they could shoot at the uniform that I wear?” Dunaski, in high dudgeon, wanted to know. That Sackett was responding to a pregnant woman needing help only added to the deep well of indignation. “We’d all worked the stretcher cars and emergency trucks and broken our necks getting to an O.B. call,” Dunaski said. “That made this case even more special.”

That summer one potential witness stayed close without the investigators having to make pests of themselves. Following the detectives’ visit in late May, Connie Trimble called Mead often, usually relating her personal problems and sometimes asking for help. At one point, Mead asked the prosecutors what they could do. “How are we going to keep in contact with this woman, for God’s sake?” she demanded. “She doesn’t have anything.” Mead ended up sending Trimble small amounts of cash, intended to be spent on necessities such as groceries and the telephone, though the detectives suspected she was drinking and using drugs. “We wanted to help her out, keep her going,” Mead said. The financial assistance was also a way to help insure the witness stayed where they could find her. The detectives knew, of course, how important Trimble was to their case, but Mead also felt a personal affinity with the troubled woman. Regardless of what she had been a part of, Mead thought, Connie had been through hard times in her life, and Mead couldn’t help but feel both compassion and a certain fondness for her.

During the summer and through the rest of the year, the task force kept working its sources, with mixed results. There were still the hard-core cop-haters who made no bones about their unwillingness to help; how much they could actually reveal was never certain, but their contempt for persons who did was plain. “I know the whole thing,” one man told Duff, “but I ain’t a snitch like some people.” Others lectured the detectives on the local civil rights movement and its heroes. A few of the no-longer-young men they tracked down readily conceded they had been “too busy pimping” or “sticking needles” in their arms to get involved with “politics.” A few admitted taking potshots at squad cars back in the day but swore they had nothing to do with killing Sackett.

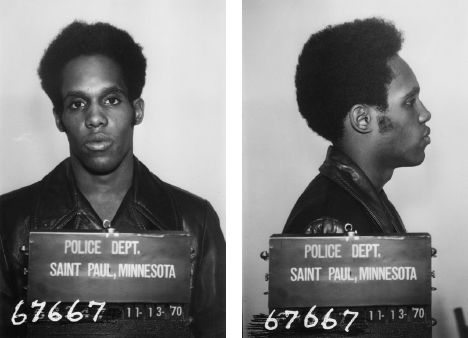

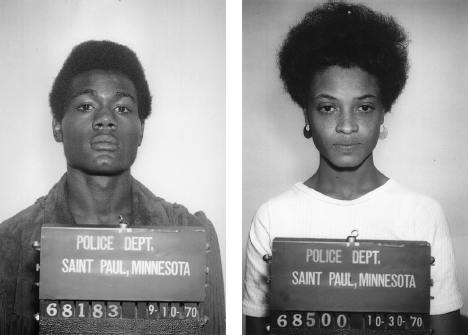

The detectives couldn’t locate Gerald Starling, whose marijuana party, Trimble continued to insist, was the reason she made the fatal call and who happened to share a Ramsey County jail cell with Reed after Reed’s arrest in November 1970. Diane Hutchinson, who had, according to Trimble, been asleep in the house she shared with Larry Clark the night of Sackett’s murder, said she knew nothing. She insisted she didn’t even recall testifying at Trimble’s trial in 1972. “I can’t remember back ten years, let alone that far back,” she told Dunaski and Mead.

More talkative, though not especially helpful, was Kofi Yusef Owusu, formerly known as Gary Hogan, who was convicted of the 1970 department store bombing. Owusu, paroled after serving only three years of his twenty-year term (presumably because of his age and good behavior while incarcerated), had long since lived in Washington, DC, where he worked for the Peace Corps, the National Black Caucus of State Legislators, and other organizations. The St. Paul investigators viewed Hogan/Owusu as one of the militant young blacks back in the day but not among the youthful crowd at the scene on the night Sackett was murdered. Now Owusu told the FBI agent and District of Columbia detective who called on him at the task force’s request that he corresponded with Trimble when she was in jail and was still friends with Reed. He referred to Reed’s job and residence in Chicago and said his friend had “gone citizen.”

A couple of years earlier, Owusu went on, Reed had visited him in Washington. While in town, he said, Reed had toured the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial, where he located James Sackett’s name among the thousands of fallen policemen and women; Owusu said he had done the same thing during an earlier visit to the site. Why they visited the memorial was apparently not discussed. The FBI report said only that, according to Owusu, the two men “briefly discussed finding the officer’s name on the wall as a mere curiosity.” As for Sackett’s murder, Owusu said he had heard the commotion from the bedroom window of his grandmother’s house but didn’t know what had happened until the next day.1

Closer to home, the detectives talked to a man named Donald Walker, who recalled attending meetings at which Reed and Clark, claiming to be Panthers, quoted from Mao’s Red Book and inveighed against capitalism and the police. More important, Walker told Dunaski and Rob Merrill that at least twice during that period Reed and Clark had asked him to stow a rifle, wrapped in a “sheet type” cloth, in the trunk of his car. Walker was away, in the Army, when Sackett was killed.

Besides Trimble and Eddie Garrett, whom the detectives were assiduously cultivating in 2004, no one, however, would prove more important to the case than an inmate at the federal penitentiary in Oxford, Wisconsin. Not that John Griffin would be readily amenable to helping the cops, especially in light of the fact that one of the detectives had helped put him in prison on a drug charge.

Mead was reading a list of possible witnesses she had assembled from police records and other sources when she came to Griffin’s name. “Well, hell,” Dunaski said. “I pinched that guy for dope back in about eighty-nine. He should still be in the pen.”

Griffin had been part of the group of young men who congregated in the Hill’s hangouts in the late sixties and early seventies and had reputedly been close to Reed for a while. Though some sources identified him as an actual Panther who had been “sanctioned” by the national organization while on a trip to California, others said he was more accurately described as a burglar and stickup man with a serious drug habit. He had been in and out of prison for most of his adult life, and, when Dunaski and Mead first went to see him at Oxford, he was about halfway through a thirty-year sentence. Arrested in a heroin bust, he had turned down a plea bargain of ten years, was convicted at trial, and received 360 months in federal prison. Griffin was a bitter man with a fearsome appearance. Stabbed with a ballpoint pen during a prison fight, he was blind in one eye and saw poorly out of the other.

Sitting down with Griffin was difficult for everybody—“like sandpapering a bobcat’s ass in a phone booth,” as Dunaski memorably described the first meeting. “He about went nuts.”

But the investigators would visit Griffin at Oxford several times. On one occasion, they brought along Bill Finney, who had known the prisoner when they were kids. Another time, the investigators brought Griffin a new pair of eyeglasses. Jeff Paulsen, the federal prosecutor, called on Griffin as well, to discuss the possibility of a sentence reduction in exchange for his testimony in the Sackett case. “We started seeing the human side of him, and he started seeing the human side of us,” Dunaski said later. “That’s what it takes, and that’s why it takes so long to develop that relationship where they start trusting you and open up.”

Griffin did not, however, open up without some incentive. While he did tell Dunaski and Mead he had valuable information about Sackett’s murder, he wanted to speak to a lawyer before deciding if he would tell them what he knew, and he wanted to speak further with the prosecutor about the chances of reducing his prison time.

The investigators were also during this period reexamining the physical aspects of the case. That meant revisiting the crime scene and pressing their search for the murder weapon.

Scott Duff was the task force’s logistics and firearms expert, and one day in August 2004 he recalculated the ranges from several plausible sites to the spot where Sackett was struck. Such estimates had been made during the original investigation, of course, but this time Duff used an electronic range-finder and Tom Dunaski served as the “target” standing at the front stoop of 859 Hague. The readings, taken at points between several of the houses on the south side of the street kitty-corner from the target, ranged from fifty yards at the corner to 102 yards near Larry Clark’s former residence—all of which would have been within a realistic striking distance of a shooter with a scope and a few practice sessions behind him.

The neighborhood itself had not changed much so far as the investigators could determine. The two blocks of single-family homes, duplexes, and small apartment buildings did not look greatly different from how they appeared in the crime-scene photos taken moments after the shooting, or, for that matter, when Glen Kothe stopped there with Duff two years later. The street lighting had been improved, and several of the majestic elms, ravaged by disease, had been replaced by smaller trees. But the lawns were green, the elms’ successors were in full summer splendor, and the street itself seemed an improbable spot for the assassination of a police officer. The nondescript frame house on the northeast corner of Hague and Victoria had been freshened up. Newer awnings shaded the windows on the west side, and a built-up set of stairs led to the back door where Kothe had hollered to his partner to watch out for a dog.

In addition, Duff made four separate test drives from the southwest corner of Selby and Victoria—where Trimble’s phone booth once stood—to the backyard of 882 Hague, where Clark had been living and where Trimble said Reed had driven after making the call. Duff covered the .15-mile distance in between twenty-seven and thirty-one seconds. On yet another occasion, Duff followed the route that Sackett and Kothe had taken on May 22, 1970. Without using red lights or siren, Duff made the roughly two-mile trip from the Capitol to 859 Hague in six minutes.

One day, Duff drove up to Kothe’s home north of the Twin Cities. The two men once more reviewed Kothe’s experience on the night of the shooting. Afterward, at Duff’s request, they went outside and Kothe lay down in the position in which he recalled Sackett had fallen. Duff took Polaroid snapshots of Kothe on the ground for the files.

About the same time, the investigators received word from an informant regarding the location of the assassin’s rifle. The weapon was rumored to have suffered several different fates—cut into pieces and thrown in the trash, tossed from either the Lake Street Bridge or the High Bridge into the Mississippi, or buried at some undisclosed site in the city. At any rate, for many years the gun was believed to be gone for good. The informant’s tip not only suggested the rifle still existed but made a find seem distinctly possible. The word was that the rifle, having been moved among several hiding places, had been secreted in its current spot since 1986.

For the investigators, the rifle would be a tangible piece of evidence in a case with precious few such pieces. It was possible, though not highly probable, that the weapon would bear the killer’s fingerprints all these years later and that those prints would be legible and distinct from those of the other individuals who might have handled the gun over time. DNA evidence, unrecoverable in 1970, was another possibility. The actual rifle, moreover, would increase the chances of the investigators connecting the recovered slug with the weapon that fired it and perhaps, if a serial number had not been erased, its provenance. (The odds were good that it had been stolen.) A short time earlier, the BCA had reexamined the jacket from the fatal bullet, and the results allowed the investigators to narrow the likely types of rifle used in the murder to two: a .30–30 and a .30–06 bolt-action hunting rifle. Finally, juries tend to be impressed when a prosecutor holds aloft the “actual murder weapon,” which if nothing else provides a tangible connection between the victim and his accused killer.

Armed with detailed directions from their informant and a search warrant signed by a Ramsey County judge, the detectives descended into the basement of a house on Concordia Avenue, once the residence of one of Reed’s associates. They removed per their instructions a length of air duct—Dunaski, the former “tinner,” knew a little something about ductwork. But in the camouflaged stash space they found nothing.

They were surprised and disappointed. The informant was reliable, the address was plausible, and the instructions were spot on—“everything was as described,” the detectives noted in a subsequent report. So, assuming the rifle had in fact been there, what had become of it, and where was it now?

Perhaps whoever had updated the ductwork discovered the gun and innocently removed it. With that possibility in mind, Duff tracked down the contractor in a Minneapolis suburb. Amazingly, when the detective identified himself on the phone, the man asked, “Are you calling about the gun in the ductwork?” Excited again, Duff and Dunaski hurried over to St. Louis Park in the west metro. But when they arrived, they learned that the gun the contractor had discovered was a .45-caliber pistol, not a bolt-action rifle, and that the ductwork he had installed was at a different St. Paul address.

So how many St. Paul basements, the frustrated detectives had to wonder, had firearms tucked away among the flues and pipes?

Jeff Paulsen was looking for a way to prosecute the Sackett case in federal court. Paulsen and Dunaski had successfully collaborated on federal prosecutions of the earlier high-profile cold cases and wanted to proceed similarly with Sackett. The problem was finding an applicable federal statute. In most situations, the murder of a municipal police officer, like the murder of an ordinary civilian, was prosecuted under state law—so what, in Sackett’s case, might allow a federal prosecution, with its generally more stringent rules and tougher penalties, including, in some instances, a sentence of death?

“We looked at everything,” Paulsen said later, referring not only to his office but to the FBI and the Justice Department in Washington. “That included civil rights violations and even treason, believe it or not. It was writ large that the ultimate goal of the Black Panther Party was the violent overthrow of the government, and Sackett’s assassination could be viewed as a step toward that. But, obviously, [treason] was pretty tenuous.” Other possibilities, such as murder in aid of racketeering activity, did not become federal law until years after the Sackett murder and could not be applied retroactively. Still others, including the murder of a state employee because of his or her race, had not become a federal offense until later. Paulsen eventually decided that to proceed behind such questionable charges would pose too great a risk to their case. Better at this stage in the investigation to offer his temporary services, with the U.S. Attorney’s blessing, to Ramsey County as a special assistant county attorney, urge the county to convene a grand jury, and help try the case under state law.

It would be an unusual step. Paulsen could think of a couple of instances in which a state prosecutor had functioned as a special assistant federal attorney but not of a single case where it proceeded the other way around. But his boss at the time, U.S. Attorney for the District of Minnesota Thomas Heffelfinger, gave him the green light, and he joined forces with Ramsey County prosecutor Susan Hudson, with the federal government paying his salary for the duration.

Ramsey County Attorney Susan Gaertner and prosecutors Hudson and Paulsen agreed that the time had come to ask the grand jury to hear evidence in the Sackett case. The list of cooperative sources had reached a more or less critical mass, but many of the individuals were considered shaky—vulnerable to pressure from family and community members and capable of memory failure, second thoughts, or flight. (Anybody who had studied the Sackett history would be aware of the Kelly Day no-show during Connie Trimble’s trial.) A grand jury would compel by subpoena skittish witnesses to testify under oath and document their sworn testimony for later use at trial. And it would be the grand jury’s job to return the indictments directing the arrest and trial of the suspects, if the grand jurors believed the evidence justified such action.

Beginning on August 25, 2004, the Ramsey County grand jury met three times to hear testimony concerning the murder of Patrolman Sackett. The witnesses called and examined by Paulsen, Hudson, and the unidentified jurors included Glen Kothe and Scott Duff, who re-created the event and provided logistical detail, and several men who had known and associated with Reed and Clark at and around the time of the murder. There was a woman, too—Constance Louise Trimble, who had returned to St. Paul from Denver to testify. Though the task force detectives had talked to her many times on the phone since they visited in late May, none had seen her until that morning. Given her condition when they left Colorado, the cops were crossing their fingers that the woman who appeared would, as she might say herself, “have it together.” She did. As a matter of fact, when she walked into the Ramsey County Courthouse with grandson Eddie Coleman, the investigators couldn’t have been more pleased.

“Oh, my gosh!” Mead said later. “She looked great. She had makeup on, and she was beautiful.”

Her state of mind seemed to have brightened, too. “She was very positive about things,” Dunaski noted.

To Mead, the improvement in Trimble’s appearance and outlook reflected her belief, in the detective’s words, “that this was important—that she was important. I think she felt she was doing the right thing.”

In her lengthy testimony Trimble confirmed what she had related to the investigators in May: that Reed had told her what to say when she made the phone call, though she didn’t know, and didn’t think Reed knew, the real objective of the call; that immediately after making the call Reed drove her and their baby the block and a half to Clark’s house, where Clark was waiting outside the back door wearing a raincoat; that while she was inside, in Clark’s bathroom, Reed and Clark may have been in the kitchen or outside—she didn’t see them for a few minutes; and that after the brief visit, Reed drove her and the baby home, where she went to bed and he left for parts unknown; that the following day, when she first learned of Sackett’s murder, Reed said their lives would be in jeopardy if she said anything about their activities the previous night. She said he told her, “You could be killed. The baby could be killed. I could be killed.”

She was older now and “closer to God,” Trimble told the grand jury. She had come close to telling what she knew many times and wished she had done so years earlier. “I was never afraid of Ron Reed,” she said at one point. “I was afraid of what I didn’t know and who was behind Ron Reed”—though she didn’t shed any light as to who that might have been.

Other witnesses testified about the times, the Inner City Youth League, the effort to establish a Black Panther chapter in St. Paul, “police oppression,” “black empowerment,” the meetings, guns, and furious rhetoric. Also described was the heady mix of global revolution and local street crime that attracted many young people. “We went over to the West Bank and robbed some hippies for a bunch of weed,” one witness recalled of a not-atypical adventure. Sometimes the recollections were mistaken. Once again the deadly 1976 shooting of Reed’s friend Freddie Price was conflated with Sackett’s murder. Occasionally the testimony reflected the rueful self-understanding that sometimes comes with advancing age. Everybody was aware of the Panther movement at the time, one man said, and “we all wanted to identify with it.… That’s the way we thought back then—you know, revolution. ‘We need to do something for the community. We need to do something drastic.’” Ronnie, Larry, and a few others were “into it—you know, the tam, the black jacket, the buttons, the look, the imagery.” But this witness said he himself was never a “real card-carrying Panther,” adding, “I would have liked people to think that I was. But I wasn’t.”

Witnesses said that prior to Sackett’s murder there was a great deal of anger and violent talk about letting “the pigs know we are tired of this shit”—which included the fatal police shootings of Barnes and Massie in February. “We got to do something back,” said one witness. “You know, we got guns!” After the officer’s murder, there was “celebration” and “bragging.” Nobody who testified said he or she witnessed Reed or Clark (or anyone else) shoot Sackett, but many of their acquaintances seemed to believe one or the other had done it. “Why not?” said one man. “That is what they preached.” Another witness was more specific: a couple of weeks after the murder, Clark said, “Yeah, we took care of business. We did what had to be done.” And a short while after that, the witness said, Clark told him that “Ronnie did it” and had used Connie to make the phone call “because they were sure she wouldn’t tell.”

John Griffin, having established a level of trust with Dunaski and Paulsen, had agreed to tell the grand jury what he knew, despite the fact, he said, that the government “[hadn’t] really offered anything in return.” What the government had done, Paulsen explained, was agree to make a motion to Griffin’s sentencing judge requesting a reduction of Griffin’s term, provided he offered “substantial assistance” in the Sackett case; any decision regarding his sentence would be up to the judge. But Griffin said he was also motivated by letters sent to him in prison by Jeanette Sackett. (At the investigators’ suggestion, Jeanette had written to Griffin as well as to Trimble, asking for cooperation.)

Griffin described himself to the grand jury as an authentic Black Panther who hung around with Reed, Clark, Day, and the others and occasionally resorted to robbery to help fund Panther-style community activities, such as free breakfasts for neighborhood kids and lunches for the elderly. He said Reed, who was “knowledgeable” about black history, Communism, and other “political things,” had emerged as the group’s leader, believing that “we should get on the map … and that we needed to, you know, spread our wings and make a statement.” Reed was especially focused on the police, who, Griffin said, were “coming into the black community” and beating people up. “And then the conversation came around to killing a cop,” he said.

Griffin himself was in prison from the summer of 1969 until the late winter of 1971. But when he got out and returned to St. Paul, he said, Day showed him the rifle that Day said had been used to kill Sackett. He repeated a long, convoluted story that he said Day told him about how Reed shot the officer, Clark shoved the murder weapon in some bushes, and Day eventually ended up with the gun—the .30–06 bolt-action rifle that Day was showing to Griffin. Later, during Trimble’s trial, he said, Reed contacted him from the Nebraska prison where Reed had been sentenced for the attempted bank robbery and asked him to keep Day from testifying against Trimble. Reed told him, he said, that if Trimble was convicted, she could “hurt him really bad.” (Reed also told him, Griffin said later in his testimony, that he never told Trimble the truth about the shooting, which would seem to raise the question of why Reed thought Trimble could “hurt” him.) Griffin said he and another, unnamed person did in fact hold Day at gunpoint to prevent him from going down to Rochester to testify. Day did, however, appear in court the day after he was called by the prosecution, apparently none the worse for wear, though he was now unwilling to take the stand. For that, Griffin said, Reed had been grateful. So grateful, Griffin said, that years later, when both men were out of prison and back in St. Paul, Reed thanked him for his help—and then, incredibly, described for him Sackett’s murder.

“When I pulled back the bolt and locked the bullet in and put the bead on that dude, I felt more powerful than I’ve ever felt in my life,” he quoted Reed as saying. “Then, when I pulled the trigger and I knew it hit him, I really felt fucked up.”

A few moments later, Griffin told the spellbound grand jurors, “All of us had the propensity for violence. That’s what we did. But Ronnie was taking it to another level.”

The Ramsey County grand jury indicted Ronald Reed and Larry Clark on Wednesday, January 12, 2005, and a Ramsey County district court judge promptly issued felony murder warrants for their arrest.

Two days later, at about a quarter to four in the afternoon, near the intersection of Penn Avenue North and Twelfth Street, a pair of Minneapolis squad cars, acting on the Ramsey County warrant, stopped a brown Ford pickup truck with South Dakota license plates and took its sole occupant into custody. Moments later, Tom Dunaski, Jane Mead, Scott Duff, Rob Merrill, and other members of the task force, tipped that Larry Clark—who was said to attend Friday prayer services at a North Side mosque—was in the area, arrived at the scene. Dunaski and Duff put the unresisting Clark in the back seat of an unmarked car and advised him of his rights. Clark refused to acknowledge the rights that were read to him or to make a statement. It was a cold, wet, midwinter afternoon, and, according to the subsequent police report, the prisoner’s only comment was a request to turn up the heat in the car.

Reed was arrested a few hours later, at his home on Chicago’s South Side. Apprehended without a struggle by members of Chicago’s cold-case squad acting on the Minnesota warrant, he was advised of his rights and driven to the Cook County jail. If Reed said anything of note that evening, the Chicago cops didn’t record it.

Despite the arrests, the St. Paul investigators weren’t popping champagne, nor were the prosecutors in either the federal or the Ramsey County courthouse. After a two-and-a-half-year paper chase, after tracking down and interviewing dozens of sources, after three sessions of a grand jury and the indictment of two suspects, they still had no confessions, no eyewitnesses, and no murder weapon. Many of their witnesses—assuming those witnesses would be there for them when the case went to court—were not the kind of citizens a jury would eagerly embrace. Then there was the fact that thirty-five years had passed since the crime. Could even the most credible individual be trusted to remember critical information from that far back in the past?

The cops and the prosecutors agreed: difficult as the case was to investigate, it would be at least as difficult to win a conviction at trial.

“We never knew how it was going to turn out,” Jane Mead said much later. “Frankly, we thought that if we got them indicted, we won. We never thought the case would be a slam dunk in the courts.”

Jeff Paulsen told the detectives, “The good news is, they’re indicted. The bad news is—they’re indicted.”

The arrests were front-page stories in the Twin Cities papers, never mind the fact that many readers and perhaps some of the reporters had not been alive when James Sackett was murdered. Though neither the investigators nor the suspects were quoted, plenty of other interested parties were. One of his Chicago neighbors told the Star Tribune’s Joy Powell that Reed was a quiet man who minded his own business. His daughter, Cherra, who was living with Reed at the time, told Powell that her father’s “mantra” was “Be responsible.” “We just knew him as our dad,” she said. Powell said Clark’s stepfather, Phillip Porter, told her that the family was shocked by the arrests, though he hadn’t spoken to Clark in several years.

Several Twin Citians weighed in on the distant times disinterred by the arrests, offering their perspectives on the Black Panthers and other exotic life forms of the era.

“People had decided they weren’t going to take it anymore,” Bill Finney told Star Tribune columnist Nick Coleman. “We were all revolutionaries back then, but we didn’t all take the same path.”

Longtime members of the Summit-University community may—or may not—have captured the current ethos of the neighborhood following the arrests.

“There were rumors circulating about this for thirty-five years,” Nick Khaliq, St. Paul’s NAACP president, told Coleman. “So for this to come to a head now makes people wonder whether [the police] have their facts right, or if the clock is ticking and they have to hurry up and rush to judgment. You think things are getting better, and then you wonder if we are going backwards. There are a lot of mixed feelings.”

Educator and neighborhood activist Kathleen (“Katie”) McWatt surely summed up the situation as succinctly as humanly possible that day. She told Coleman that she was “amazed” when she heard about the arrests, then added, “Those times seem so far in the past. But here we are.”