‘I vow to God I don’t know what I shall do with my awkward son Arthur,’ complained Lady Mornington to her daughter-in-law in 1785. Twenty-eight years later Arthur’s star was set to eclipse the careers of two of his highly successful brothers and the best was still to come. Yet it had not been an easy road to success and one quite unlike that trodden by his nemesis, Napoleon Bonaparte. His baptism of a ‘real’ battle, in command of the 33rd Foot at Seringapatam, had been a disaster. During a night attack on a copse he had ‘lost’ his battalion and on return to the British camp had burst into tears exclaiming through his violent sobs that he was ‘ruined forever’. Indeed, it would have been so had it not been for his political connections; the governor-general of India was Sir Arthur Wellesley’s (latterly 1st Duke of Wellington, 1769–1852) elder brother.

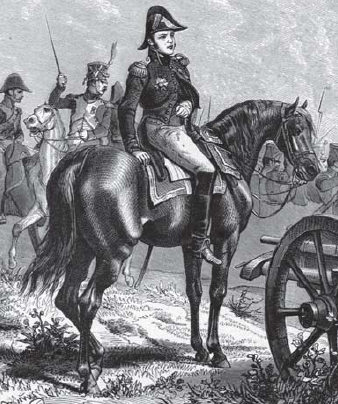

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington (1769–1852). Commander-in-chief of the Anglo-Portuguese and subsequently the allied armies in Iberia and southern France. Wellesley was created a viscount following his victory at Talavera and promoted to Field Marshal after Vitoria. He became a duke in May 1814 at the end of the Peninsular War before going on to defeat Napoleon at Waterloo. Painting after George Dawe, c.1818. (National Army Museum)

He was given another chance. It was an opportunity the young Arthur was not to squander. In 1805, when he returned to England, the military and political lessons learned from his mistakes and successes were the cornerstones of his future career. His use of ground, his understanding of infantry tactics to maximize firepower, his expertise in weaving the (available) fighting components on and off the field of battle, his determination for intelligence and his consideration of logistics but above all the importance of integrating allied (and local) forces and political interaction at both the micro and macro levels were traits he developed and honed in the Peninsula. From his early success in the rolling hills at Vimeiro in 1808 to his latest unequivocal victory on the plains of Vitoria, where he earned his field marshal’s baton, Wellington’s standing and reputation in 1813 was unsurpassed since the Duke of Marlborough.

Wellington, however, despised gratuitous advice and found it difficult to delegate command. Following the debacle on the east coast at Tarragona when General John Murray abandoned the siege, 18 guns and the local Spanish forces (for which he was later tried by court martial) it was clear that Wellington needed to send a commander to grip the situation. The reality was that he had none he could spare. General Sir Thomas Graham, who had overseen the siege of San Sebastian, returned to England when his ‘eyes had given out’. The other three candidates were needed with the main army. The first of these men, Lieutenant-General Rowland ‘Daddy’ Hill (1772–1842), was undoubtedly Wellington’s most trusted lieutenant. He had served at Toulon and Egypt but made his name in the Peninsula commanding brigades at Vimeiro and La Coruña, his beloved 2nd Division at Talavera and then subsequently in an independent role guarding the southern corridor to Lisbon. Wellington developed a trust for Hill describing him as a man who ‘does what he is told’. He proved his worth in 1812 as part of the deception operations prior to the Salamanca campaign where he destroyed the bridge at Almaraz thereby denying the French armies north–south connectivity. He had been entrusted with a corps at Vitoria and given the task of capturing the Puebla Heights, a mission he completed with his, by now, characteristic skill. Having moved, as instructed, north along the ridge at Buçaco in 1811 to support Lieutenant-General Picton against General Reynier’s attacks, Wellington commented that ‘the best of Hill is that I always know where to find him’. With the extended operations in the Pyrenees and southern France, it was a quality Wellington was to exploit with regularity.

Lieutenant-General Rowland Hill (1772–1842). ‘Daddy’ Hill was one of Wellington’s most trustworthy lieutenants, who led from the front. He was well known for the compassion he demonstrated to those under his command but he was also brave and resourceful. Painting after George Dawe, 1819. (National Army Museum)

The second of these right-hand men was Lieutenant-General William Carr Beresford (1768–1854). Beresford had also served at Toulon and then moved to command the Connaught Rangers in India before being given a brigade in Egypt. Forced to surrender his brigade during the ill-fated Buenos Aires expedition he was subsequently appointed governor of Madeira, an appointment which provided him the perfect portfolio to assume command of the Portuguese Army in March 1809. He was made a marshal of the Portuguese Army as a result. He was an excellent organiser and administrator; traits which enabled him to train, equip and integrate the force to create an Anglo-Portuguese army from the end of 1809 until the end of the war. However, following his questionable performance in command at Albuera in 1811, his ability to command troops in contact was open to question. Nevertheless, Wellington realized that he had in Beresford another man he could trust and he was allocated a number of corps-level commands during the final few months of the war.

Lieutenant-General William Carr Beresford (1768–1854) was a better administrator than soldier, despite being undeniably brave. Following Beresford’s performance at Albuera in 1811, Wellington always kept a close eye on him when in command of men but trusted his judgement on other matters. Unknown artist. (National Army Museum)

Lieutenant-General Sir John Hope (1765–1823) replaced Graham as the left wing commander of the Allied Army in October 1813. Another brave commander, he took fearful risks causing Wellington to declare that ‘we shall lose him, however, if he continues to expose himself in fire’. Engraving by Vendramini. (Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

The third of his key subordinates was Lieutenant-General John Hope (1765–1823), who had seen early service under Abercromby in the West Indies, and served in the Low Countries and Egypt where he was wounded at Alexandria. He commanded the southerly column during Sir John Moore’s advance into Spain at the end of 1808 and then assumed command of the army at La Coruña when Moore was mortally wounded. Despite service at Walcheren he did not return to the Peninsula until 1813 when he assumed command of the left wing of the army on General Graham’s return home. He was undoubtedly a brave man and a good leader but whether he possessed strategic vision is debatable.

The only other lieutenant-general in Wellington’s force was Stapleton Cotton (1773–1865), the commander of the cavalry. He had arrived in the Peninsula in 1808 and assumed command of the cavalry in June 1810. His relationship with Wellington was mixed and although he is known to have stated that ‘he is not exactly the person I should select to command an army’ Wellington did, nevertheless, recognize his talents and considered him his best cavalry commander.

His divisional commanders were, inevitably, a mixed bag. Perhaps his best three were Thomas Picton (1758–1815) commanding the 3rd ‘Fighting’ Division, Galbraith Lowry Cole (1772–1842) commanding the 4th Division, and Charles Alten (1764–1840) commanding the Light Division. Much has been made of Picton’s character, capitalizing on Wellington’s observation that he ‘found him a rough foul-mouthed devil as ever lived’. He was, undoubtedly, an uncompromising Welshman but also a first-rate divisional commander and an extremely brave officer. However, Wellington wisely kept him on a relatively tight rein. Cole was another excellent divisional commander but was another man who performed better under the watchful eye of Wellington than in an independent role. Alten was, as one might expect from the commander of the army’s elite division, a cool customer but a very professional soldier who was held in high esteem by his men. A lesser man would have found the shoes of his predecessor, ‘Black Bob’ Craufurd, difficult to fill but not Alten who was more than up to the task.

Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Picton (1758– 1815) commanded the 3rd ‘Fighting’ Division throughout the Peninsular War. He was a hard disciplinarian, enormously brave with a defiant and forceful personality. He was to die on the field at Waterloo. Painting after Jenkins, 1815. (Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

Lieutenant-General Galbraith Lowry Cole (1772–1842) commanded the 4th Division from October 1809 to the end of the war. He had a short temper but was a generous man and was known as giving the best dinner parties in the Peninsular Army. He was not, however, that impressive when given a larger more independent command. Painting after Thomas Lawrence, 1816. (Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

Wellington’s Spanish commanders were far better than many British histories concede. General Miguel Ricardo Alava (1770–1843) was not a commander but was appointed early in the war to act as the Spanish liaison officer at Wellington’s headquarters. He became a close friend and even joined Wellington during the Waterloo campaign. General Pedro Agustin Giron, Duque de Ahumada (1788–1842), had led the 4th Army during the Vitoria campaign and, much to Wellington’s annoyance, had been removed from his direct command by the Spanish government shortly after. However, Giron was placed in command of the Army of Reserve of Andalusia and returned to the front under Wellington’s command in that capacity. Major-General Pablo Morillo, Conde de Cartagena (1778–1837), had led a division (with Hill’s corps) at the battle of Vitoria where it had fought with great tenacity. When Wellington was forced to send his Spanish troops for looting and ill discipline back to Spain, Morillo’s division was the one formation he retained north of the Pyrenees.

Marshal ‘Nicolas’ Jean-de-Dieu Soult, Duc de Dalmatie (1769–1851), had established his reputation long before arriving in the Peninsula. He had performed with distinction at Fleurus (under Marshal Jourdan) and then in Switzerland (under Marshal Masséna). As commander of IV Corps he led it with considerable ability and no small amount of bravery at Austerlitz, Jena and Eylau. In June 1808 he became the Duke of Dalmatia and was sent, as commander of II Corps, to Spain with Napoleon. His initial operations against the Spanish Army of the Left were well handled, as was his pursuit of Sir John Moore and the subsequent battle at the Galician port of La Coruña in January 1809.

Marshal Nicolas Soult, Duc de Dalmatie (1769–1851) was arguably one of Napoleon’s most capable marshals. A good field commander and capable administrator, he was the ideal choice to take the reins following the disaster at Vitoria and he made the last ten months of the war decidedly difficult for Wellington’s army. (Author’s Collection)

However, his Peninsular War performance, following La Coruña and Napoleon’s departure from the Iberian theatre, was decidedly mediocre. He failed to move and capture Lisbon, instead contenting himself with the capture of Oporto, where he made noises about becoming King of Lusitania. His dream was short lived as Wellington drove him from the city after a month in the most embarrassing of circumstances. He had a brief success over the Spanish at Ocaña before settling down again in a vice-regal capacity in southern Spain where he seemed content to enjoy his Spanish siesta at the expense of French cohesion and the war effort across the Peninsula. He was defeated, albeit narrowly, by Beresford at Albuera, but his lack of support for King Joseph Bonaparte and Jourdan eventually resulted in his being withdrawn from Spain.

Lieutenant-General Bertrand Clausel (1772–1842) arrived in the Peninsula in 1810 and had a number of commands from division to army. He was somewhat unlucky on occasion and not enormously popular but he served with great distinction under Soult. (Author’s Collection)

With Napoleon at his side Soult once again lifted his game, commanding his old IV Corps at Lützen and Bautzen in May 1813, to stem the tide of disaster following the ill-fated Russian campaign. With news of the calamity at Vitoria, Soult was Napoleon’s choice to return to command the new Army of Spain, establish the structure and restore the unity. He proved a worthy adversary making the final months of the war decidedly difficult for the allies, earning considerable respect from the British officers and the nickname the ‘Duke of Damnation’ from the rank and file.

Like Wellington, Soult had four lieutenant-generals under his command. Lieutenant-General Honoré-Charles-Michel-Joseph Reille (1775–1860) had a fairly undistinguished early career. He first arrived in Spain as a divisional commander, capturing Rosas in Catalonia before being recalled for the Austrian campaign. He returned in 1810 and by 1812 was commanding an ad hoc corps as part of Marshal Suchet’s forces in Aragon and lower Catalonia. He assumed command of the Army of Portugal in late 1812 and performed adequately at Vitoria. He was given command of the ‘lieutenancy of the Right’ by Soult in the new Army of Spain.

Lieutenant-General Honoré Reille (1775–1860) was a capable officer who eventually became a marshal but he did not get on well with Soult and found himself sidelined at Bayonne and quit the army. Reinstated by Paris, his relationship with Soult was never harmonious, but he served the army with great merit. (Author’s Collection)

Lieutenant-General Bertrand Clausel (1772–1842) served with some distinction during the Revolutionary Wars, most notably in the Pyrenees. He came to Spain as a divisional commander in Junot’s restyled VIII Corps and remained in the Army of Portugal following Masséna’s significant reorganization in 1811. He commanded his division at Salamanca and was temporarily in command of the army following the wounding of Marshal Marmont and death of his replacement, General Bonnet. He moved to command the French Army of the North in January 1813 and succeeded in withdrawing it intact, following the pursuit by Wellington’s forces after Vitoria. He assumed command for the ‘lieutenancy of the Left’.

Lieutenant-General Jean-Baptiste Drouet (1765–1844), better known as the Comte d’Erlon, arrived in Spain in 1810 and had a variety of commands, most notably commanding the IX Corps and the armies of the Centre and Portugal. He was a reliable field commander and a trusted subordinate of Soult. (Author’s Collection)

Lieutenant-General Jean-Baptiste Drouet, Comte d’Erlon (1765–1844), had a distinguished early career during the Revolutionary Wars, commanding a brigade at Hohenlinden and a division at Austerlitz and Friedland, after which he was given his title Comte d’Erlon. He arrived in the Peninsula as commander of IX Corps in September 1810 and took part in the battle at Fuentes de Oñoro the following year. Following the reorganization of the Army of Portugal he assumed command of V Corps in Soult’s Army of the South before moving to command the Army of Portugal and then the Army of the Centre. The latter he commanded at Vitoria. He assumed the ‘lieutenancy of the Centre’.

The fourth lieutenant-general was Honoré Theodore Maxime Gazan, Comte de la Peyrière (1765–1845). Gazan was posted to Spain in 1808 following a successful early career under the ancien régime and during the Revolutionary Wars. He commanded a division in Marshal Mortier’s V Corps and was wounded at Badajoz and Albuera. In 1813 he assumed command of the Army of the South when Soult was withdrawn but handled his rearguard role at Vitoria with little skill, exacerbating Joseph’s and Jourdan’s problems to extract their forces once the battle had been lost. He accepted the post as Soult’s chief of staff in the new Army of Spain.

Soult had a number of very capable divisional commanders within his new charge. Two deserve particular mention. Major-General Maximilien-Sébastien Foy (1775–1825) was a very capable officer who had fought well under Marshal Moreau in Switzerland and Masséna in Italy but his promotion was always constrained because of his open criticism of Napoleon’s elevation to emperor. He performed with distinction throughout the Peninsular War, initially as a colonel commanding the artillery reserve at Vimeiro, through to 1813 when, as a divisional commander, he fought a series of creditable rearguard actions following Vitoria. Although he remained a divisional commander in Soult’s new army, he was entrusted with a series of independent missions on the French left flank. Major-General Jean Isidore Harispe (1768–1855) had led and fought with his division quite brilliantly under Marshal Suchet on the east coast of Spain until being recalled in December 1813 to Soult’s Army of Spain. Being of Basque origin it was hoped that he could inspire the inhabitants of the region and was accordingly given command of the 8th Division.

Lieutenant-General Honoré Gazan (1765–1845) arrived in the Peninsula in 1808 and spent a considerable amount of that time under Soult’s command. Soult trusted him explicitly; he was undoubtedly brave and wounded on a number of occasions, but he was not the most able of field commanders. Soult made him his chief of staff. (Author’s Collection)

Major-General Jean Isidore Harispe (1768–1855). A Basque by birth, he was brought into Soult’s army to command the 8th Division in December 1813. He performed with great distinction, most notably at Orthez. Not used to fighting against British infantry he rather blundered into his counter-attack at Toulouse and was beaten back, losing his foot to a round shot in the process. Painting after Jean Rixens. (By kind permission of the Musée Basque)