Allied troops entered Paris on 31 March but it was not until 4 April that Napoleon signed a tentative abdication and a further two days before the details were settled. Rumours reached southern France but there was nothing definitive. Tragically, the nearly 8,000 men killed or wounded following the struggle for Toulouse on 10 April had suffered and died needlessly. It was an inappropriate curtain to the war. As Wellington was being mobbed by an enthusiastic crowd in the city square, Colonel Ponsonby rode in (having been dispatched by Lieutenant-General Dalhousie in Bordeaux) with confirmation of Napoleon’s final abdication on the 6th. The city celebrated and hastily prepared a gala performance of Richard Coeur de Lion in triumph.

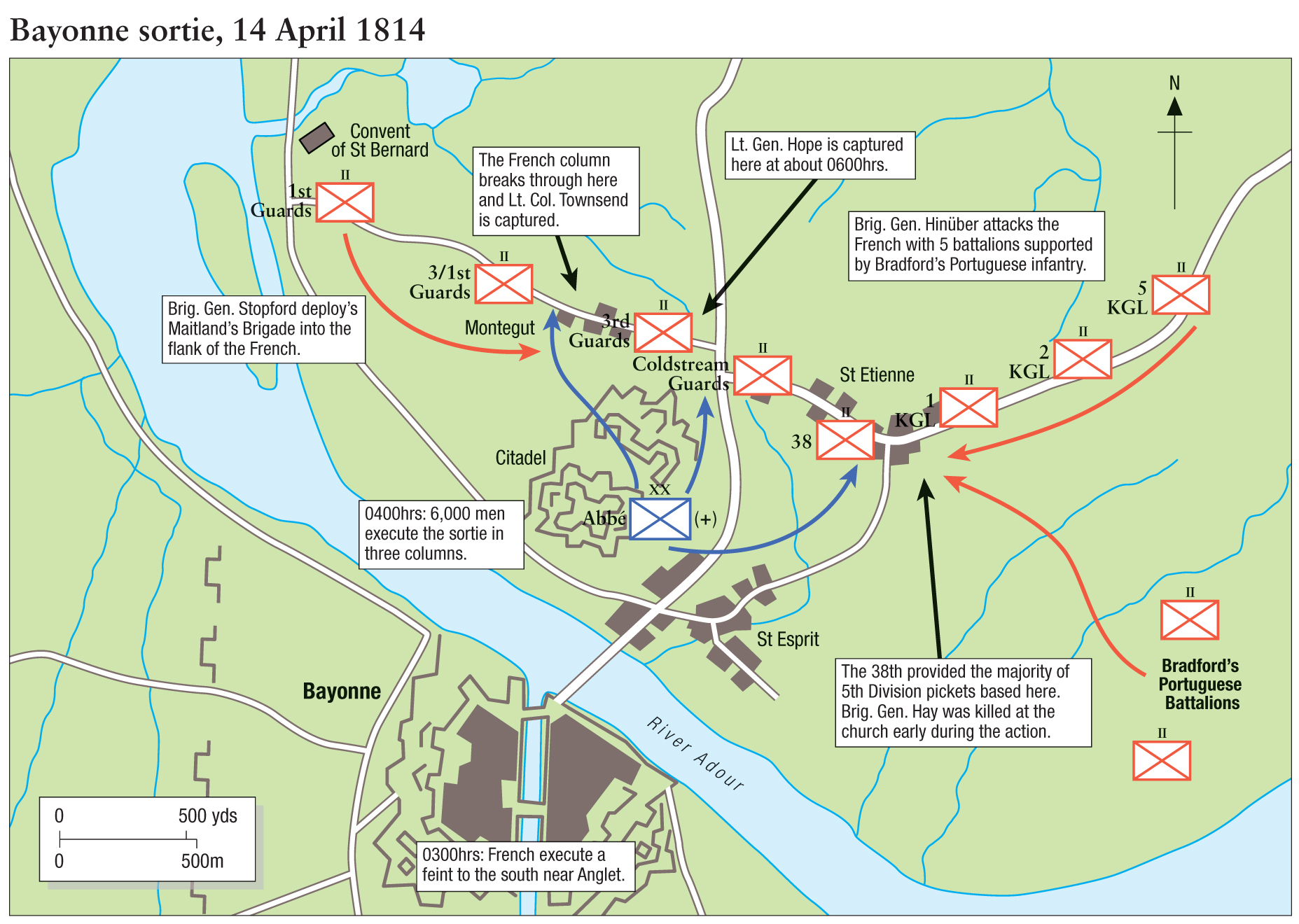

Soult received the news the next day on the road to Carcassonne. He was shocked by the reports but appalled to note that the new Minister of War was General Pierre Dupont, the ‘Bungler of Bailén’. He was not prepared to sign an armistice until, as he saw it, solid evidence as to the legality of the warrant could be obtained (which arrived five days later). This was not, however, the end of the matter for there are two additional sagas to recount. The first took place at Bayonne on 14 April when Thouvenot, with a rush of blood to the head, decided to execute an extensive sortie on Hope’s line, north of the Adour. He assembled Abbé’s division, supplemented by some hand-picked battalions from the garrison, and before dawn these 6,000 men disgorged from three exits to the north of the city and fell upon the investment. Batty recalled that ‘two columns of the French rushed forward with loud cheers of En Avant, En Avant; and by their overpowering numbers, broke through the line of picquets between St Etienne and St Bernard’. Major-General Andrew Hay was in command of the outposts and was killed at the village church of St Etienne. Meanwhile, Sir John Hope, who had gone forward at the first alarm, was wounded and captured. This disruption in command delayed the Allied counter-attack; Lieutenant-General Howard took stock of the situation and issued orders to Stopford and Maitland, while Hinüber acted on his own initiative and, supported by two Portuguese battalions, commenced the counter-attack at St Etienne.

The sortie from Bayonne in the early hours of 14 April. Another all-encompassing scene by Heath, which appears to depict the attack on St Étienne with the Guards on the right and the 38th on the left. The officer falling from his horse in the centre is presumably Hay, while that trapped under his charger in the foreground is Hope. (Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

This engraving by an unknown artist is also inaccurate. Hope was shot and wounded in the shoulder as he moved down the hollow road to St Étienne; his charger was killed at the same moment and he was trapped under the beast. Two of his ADCs (Herries and Moore) tried to extricate him and all three were taken prisoner. (National Army Museum)

The French force began to pull back into the citadel bringing to an end this sorry episode. Allied casualties numbered 150 killed and 457 wounded, while French losses were 111 killed and 780 wounded. Damage to the defences was minimal and, as the guns had not yet been deployed in the battery positions, no great materiél loss was suffered. Although Thouvenot had not received official notification of Napoleon’s abdication, or orders as to his immediate course of action, he was not being, or about to be, attacked. His defence to that point had been conducted passively. Furthermore, he was certainly in possession of sufficient information about events in Paris as to raise serious doubts about his motives on 14 April. The official order came on 27 April from Soult, and Batty recalled that ‘on the 28th of April, at mid-day, the white flag was hoisted in the citadel, and in the grande place of the town; the whole garrison was under arms, and a salute of three hundred rounds from their artillery complimented the re-appearance of the ancient standard’.

The sortie at Bayonne was not, in fact, the last act of the war. Two days later, General Habert conducted a sortie at Barcelona against the Allied blockading force. Like Thouvenot’s attempt at Bayonne, it achieved little but unlike Thouvenot, Habert had mitigation as he certainly did not possess news of Napoleon’s fate or of recent activity in Paris. After six long years, the war in the Peninsula and southern France was finally over and, for the British (and Portuguese), it was about to become a glorious memory.

From the commencement of this wonderful struggle, in August 1808, to April 1814, more battles had been fought (all of them won) than England could boast for nearly a century; and the triumphant march of the army of Wellington was uninterrupted by one defeat, until the subjugation of their brave opponents was complete, which forbade further hostile advance upon the French territory.

Captain William Grattan – The Connaught Rangers