Introduction

THE CHINESE POETIC tradition is the largest and longest continuous tradition in world literature, practiced until recently by virtually everyone in the educated class and stretching from well before 1500 B.C.E. to the present. Remarkably, it has flourished not only in its homeland but also in Korea and Japan, each of which systematically adopted Chinese language and culture and thereafter developed Chinese poetic practice into their own directions. Much later, at the beginning of the modernist revolution, classical Chinese poetry made a surprising appearance in translation far from home when Ezra Pound saw in its concrete language and imagistic clarity a way to clear away the formalistic rhetoric and abstraction that dominated English poetry at the time. And its contemporary voice and sage insight have made it an influential strain of American poetry ever since.

This anthology presents more than three millennia of Chinese poetry from its beginnings sometime before 1500 B.C.E. to 1200 C.E., the centuries during which virtually all of its major innovations took place. In speaking of a Chinese poetic tradition, we are necessarily speaking of the written tradition. Nevertheless, the Chinese tradition was essentially an oral folk tradition for over a millennia, because the major written texts were primarily translations of folk poetry. This fact makes it difficult to assign a firm date for the tradition’s origins. Indeed, as the written tradition is quite literally an extension of the oral tradition, its beginnings stretching back almost to the very beginnings of the culture itself. So it is not surprising when literary legend tells us that an especially brief and plainspoken folk-song called “Earth-Drumming Song” originated in the twenty-third century B.C.E.

After a transitional period beginning about 300 B.C.E., a mature written tradition was established around 400 C.E., its poets typically speaking in a personal voice of their immediate experience. These poets belonged to a small, highly educated elite class of artists and scholars that ran the government. From emperor and prime minister to lowly bureaucrat, from regional governor to monk or recluse in distant mountains—they all studied and wrote poetry, and their poetry was widely read among their colleagues. It was shared first on hand-copied calligraphic scrolls, ranging from a small scroll with a single poem to a set of larger scrolls containing a collection of poems, and then, after printing came into common use during the ninth century C.E., in printed books as well. These poems tended eventually to be scattered on the winds of circumstance—war, fire, neglect—with the result that a large share of work by even the most celebrated poets has been lost, and often substantial portions of the collections we now have are of uncertain attribution.

The work of men and women, illiterate peasants and urbane aristocrats, seductive courtesans and august statesmen, shamans and monks and countless literary intellectuals with an astonishing range of unique sensibilities—there is a remarkable diversity in the Chinese tradition, but underlying that diversity lies the unifying influence of the classical Chinese language. Quite different from the spoken Chinese of farm and market, classical Chinese was a literary language alive primarily in a body of literary texts, which means that it remained relatively unchanged across millennia. The most immediately striking characteristic of classical Chinese is its graphic form: it has retained aspects of its original pictographic nature, and so retains a direct visual connection to the empirical world. This was especially true for poetry, which in its extreme concision focuses attention on the characters themselves, and for the original readers of these poems, who were so erudite that they could see the original pictographs even in substantially modified graphs of characters.

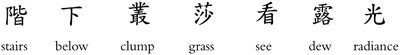

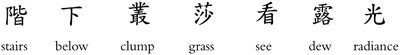

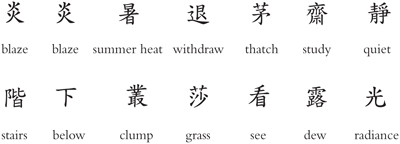

The other remarkable characteristic of the language is that its grammatical elements are minimal in the extreme, allowing a remarkable openness and ambiguity that leaves a great deal unstated: prepositions and conjunctions are rarely used, leaving relationships between lines, phrases, ideas, and images unclear; the distinction between singular and plural is only rarely and indirectly made; there are no verb tenses, so temporal location and sequence are vague; very often the subjects, verbs, and objects of verbal action are absent. In addition, words tend to have a broad range of possible connotation. This openness is dramatically emphasized in the poetic language, which is far more spare even than prose. In reading a Chinese poem, you mentally fill in all that emptiness, and yet it remains always emptiness. The poetic language is, in and of itself, pure poetry:

The grammatical openness is apparent in this line from Meng Hao-jan. And though it is not unusually pictographic, we find many images in the last four characters alone: grass ![]() (stalks and roots divided by ground level) above water

(stalks and roots divided by ground level) above water ![]() (abbreviated form showing drops of water; full form

(abbreviated form showing drops of water; full form ![]() from the ancient form, which shows the rippling water of a stream:

from the ancient form, which shows the rippling water of a stream: ![]() ); the eye

); the eye ![]() (tipped on its side in the second character) shaded by a hand

(tipped on its side in the second character) shaded by a hand ![]() (shown as the wrist and five fingers) for best vision; rain falling from the heavens

(shown as the wrist and five fingers) for best vision; rain falling from the heavens ![]() that is mysteriously seen only at your feet

that is mysteriously seen only at your feet ![]() (schematic picture of a foot below the formal element of a circle, showing heel to the left, toes to the right, leg above, with an ankle indicated to one side); and fire

(schematic picture of a foot below the formal element of a circle, showing heel to the left, toes to the right, leg above, with an ankle indicated to one side); and fire ![]() (slightly formalized as the top half of the last character, the horizontal line and above), supported by a person

(slightly formalized as the top half of the last character, the horizontal line and above), supported by a person ![]() (picture of a person walking, modified slightly in this character to give its base some structural stability, from the ancient form that includes a head:

(picture of a person walking, modified slightly in this character to give its base some structural stability, from the ancient form that includes a head: ![]() ).

).

These two defining characteristics of the language—empty grammar and graphic form—are reflected in the Taoist cosmology that became the conceptual framework shared by all poets in the mature written tradition. The cosmology must have evolved together with the language during the earliest stages of human culture in China, as they share the same deep structure, and it eventually found written expression in the Tao Te Ching (c. sixth century B.C.E.) and the Chuang Tzu (c. fourth century B.C.E.). Taoist thought is best described as a spiritual ecology, the central concept of which is Tao, or Way. Tao originally meant “way,” as in “pathway” or “roadway,” a meaning it has kept. But Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu redefined it as a spiritual concept, using it to describe the process (hence, a way) through which all things arise and pass away. To understand their Way, we must approach it at its deep ontological level, where the distinction between presence (being) and absence (nonbeing) arises.

Presence (yu) is simply the empirical universe, which the ancients described as the ten thousand living and nonliving things in constant transformation, and absence (wu) is the generative void from which this ever-changing realm of presence perpetually arises. This absence should not be thought of as some kind of mystical realm, however. Although it is often spoken of in a general sense as the source of all presence, it is in fact quite specific and straightforward: for each of the ten thousand things, absence is simply the emptiness that precedes and follows existence. Within this framework, Way can be understood as the generative process through which all things arise and pass away as absence burgeons forth into the great transformation of presence. This is simply an ontological description of natural process, and it is perhaps most immediately manifest in the seasonal cycle: the pregnant emptiness of absence in winter, presence’s burgeoning forth in spring, the fullness of its flourishing in summer, and its dying back into absence in autumn.

At the level of deep structure, words in the poetic language function in the same way as presence, the ten thousand things, and the emptiness that surrounds words functions as absence. Hence, the language doesn’t simply replicate but actually participates in the deep structure of the cosmos and its dynamic process; it is in fact an organic part of that process.And the pictographic nature of the words, enacting as it does the “thusness” of the ten thousand things, reflects another central concept in the Taoist cosmology: tzu-jan, the mechanism by which the dynamic process of the cosmos proceeds, as presence arises out of absence.

The literal meaning of tzu-jan is “self-ablaze,” from which comes “self-so” or “the of-itself.” But a more revealing translation of tzu-jan is “occurrence appearing of itself,” for it is meant to describe the ten thousand things arising spontaneously from the generative source (wu)—each according to its own nature, independent and self-sufficient; each dying and returning into the process of change, only to reappear in another self-generating form.This vision of tzu-jan recognizes the earth, indeed the entire cosmos, to be a boundless generative organism. There is a palpable sense of the sacred in this cosmology: for each of the ten thousand things, consciousness among them, seems to be miraculously emerging from a kind of emptiness at its own heart, and emerging at the same time from the very heart of the cosmos itself. As it reflects this cosmology in its empty grammar and pictographic nature, the poetic language is nothing less than a sacred medium. Indeed, the word for poetry, shih, is made up of elements meaning “spoken word” and “temple.” The left-hand element, meaning “spoken word,” portrays sounds coming out of a mouth: ![]() .And the right-hand element, meaning “temple,” portrays a hand below (ancient form:

.And the right-hand element, meaning “temple,” portrays a hand below (ancient form: ![]() ) that touches a seedling sprouting from the ground (ancient form:

) that touches a seedling sprouting from the ground (ancient form: ![]() ):

): ![]() . Hence: “words spoken at the earth altar”:

. Hence: “words spoken at the earth altar”: ![]() .

.

Although radically different from the Judeo-Christian worldview that has dominated Western culture, this Taoist cosmology represents a world-view that is remarkably familiar to us in the modern Western world (no doubt part of the reason the poetry feels so contemporary): it is secular, and yet profoundly spiritual; it is thoroughly empirical and basically accords with modern scientific understanding; it is deeply ecological, weaving the human into the “natural world” in the most profound way (indeed, the distinction between human and nature is entirely foreign to it); and it is radically feminist—a primal cosmology oriented around earth’s mysterious generative force and probably deriving from Paleolithic spiritual practices centered on a Great Mother who continuously gives birth to all things in an unending cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

By the time the mature written tradition began around 400 C.E., Buddhism had migrated from India to China and was well established. Ch’an, the distinctively Chinese form of Buddhism, was emerging in part as a result of mistranslation of Buddhist texts using Taoist terminology and concepts. Ch’an was essentially a reformulation of the spiritual ecology of early Taoist thought, focusing within that philosophical framework on meditation, which was practiced by virtually all of China’s intellectuals. Such meditation allows us to watch the process of tzu-jan in the form of thought arising from the emptiness and disappearing back into it. In such meditative practice, we see that we are fundamentally separate from the mental processes with which we normally identify, that we are most essentially the very emptiness that watches thought appear and disappear.

Going deeper into meditative practice, once the restless train of thought falls silent, one simply dwells in that undifferentiated emptiness, that generative realm of absence. Self and its constructions of the world dissolve away, and what remains of us is empty consciousness itself, known in Ch’an terminology as “empty mind” or “no-mind.” As absence, empty mind attends to the ten thousand things with mirrorlike clarity, and so the act of perception itself becomes a spiritual act: empty mind mirroring the world, leaving its ten thousand things utterly simple, utterly themselves, and utterly sufficient. This spiritual practice is a constant presence in classical Chinese, in its fundamentally pictographic nature. It is also the very fabric of Chinese poetry, manifest in its texture of imagistic clarity. In a Chinese poem, the simplest word or image resonates with the whole cosmology of tzu-jan.

The deep structure of the Taoist/Ch’an cosmology is shared not only by the poetic language but by consciousness as well. Consciousness, too, participates as an organic part of the dynamic processes of the cosmos, for thoughts appear and disappear in exactly the same way as presence’s ten thousand things. And the generative emptiness from which thoughts arise is nothing other than absence, the primal source.

Consciousness, cosmos, and language form a unity, and in the remarkably creative act of reading a Chinese poem we participate in this unity, filling in absence with presence, empty mind there at the boundaries of its true, wordless form:

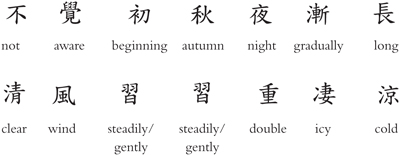

The occasion for this poem is a kind of non-occasion: Meng Hao fan’s self-absorbed failure to notice the world around him, which is a kind of exile from the very nature of language and consciousness. It is autumn that attracts Meng’s notice, bringing him back to that unity of cosmos, consciousness, and language—the autumnal world dying into winter, season of wu, that pregnant emptiness. His “thatch hut grows still,” an outer stillness that reflects an inner stillness, an emptiness.This empty self is also alive in the language, for Meng exists in the grammar only as an absent presence, almost indistinguishable from wu’s emptiness. He is felt in the first and last lines, where we can infer his presence only because of the convention that such a poem is about the poet’s immediate experience. In the last line, we can fill in the grammatical subject to get: below the stairs, in bunch-grass, [I] see dew shimmer. But the poet remains more absence than presence. Essentially an act of meditation, the poem ends with a perfectly empty mind mirroring the actual—a person become, in the most profound way, his truest self wu’s enduring emptiness and tzu-jan’s ten thousand shimmering things:

AUTUMN BEGINS

Autumn begins unnoticed. Nights slowly lengthen,

and little by little, clear winds turn colder and colder,

summer’s blaze giving way. My thatch hut grows still.

At the bottom stair, in bunchgrass, lit dew shimmers.

* * *

ALTHOUGH IT MEANS ignoring the hundreds of noteworthy poets whose work makes up the evolving texture of China’s poetic tradition, and therefore missing much important transitional material, this anthology presents Chinese poetry as a tradition of major poets whose poetics created new possibilities for the art, which is to say, gave new dimensions to the Taoist/ Ch’an unity of cosmos, consciousness, and language. In this modern age, vast environmental destruction has been sanctioned by people’s assumption that they are spirits residing only temporarily here in a merely physical world created expressly for their use and benefit. This makes the Taoist/Ch’an worldview increasingly compelling as an alternative vision in which humankind belongs wholly to the physical realm of natural process. The range of work gathered in this anthology addresses every aspect of human experience, revealing how it is actually lived from within that alternative perspective—not in a monastery but in the always compromised texture of our daily lives.