2

Oh, what bliss! was Caesar’s initial reaction to his sudden removal from the affairs of Asia Province and Cilicia—and from the inevitable entourage of legates, officials, plutocrats and local ethnarchs. The only man of any rank he had brought with him on this voyage to Alexandria was one of his most prized primipilus centurions from the old days in Long-haired Gaul, one Publius Rufrius, whom he had elevated to praetorian legate for his services on the field of Pharsalus. And Rufrius, a silent man, would never have dreamed of invading the General’s privacy.

Men who are doers can also be thinkers, but the thinking is done on the move, in the midst of events, and Caesar, who had a horror of inertia, utilized every moment of every day. When he traveled the hundreds, sometimes thousands, of miles from one of his provinces to another, he kept at least one secretary with him as he hurtled along in a gig harnessed to four mules, and dictated to the hapless man non-stop. The only times when work was put aside were those spent with a woman, or listening to music; he had a passion for music.

Yet now, on this four-day voyage from Tarsus to Alexandria, he had no secretaries in attendance or musicians to engage his mind; Caesar was very tired. Tired enough to realize that just this once he must rest—think about other things than whereabouts the next war and the next crisis would come.

That even in memory he tended to think in the third person had become a habit of late years, a sign of the immense detachment in his nature, combined with a terrible reluctance to relive the pain. To think in the first person was to conjure up the pain in all its fierceness, bitterness, indelibility. Therefore think of Caesar, not of I. Think of everything with a veil of impersonal narrative drawn over it. If I is not there, nor is the pain.

What should have been a pleasant exercise equipping Long-haired Gaul with the trappings of a Roman province had instead been dogged by the growing certainty that Caesar, who had done so much for Rome, was not going to be allowed to don his laurels in peace. What Pompey the Great had gotten away with all his life was not to be accorded to Caesar, thanks to a maleficent little group of senators who called themselves the boni—the “good men”—and had vowed to accord nothing to Caesar: to tear Caesar down and ruin him, strike all his laws from the tablets and send him into permanent exile. Led by Bibulus, with that yapping cur Cato working constantly behind the scenes to stiffen their resolve when it wavered, the boni had made Caesar’s life a perpetual struggle for survival.

Of course he understood every reason why; what he couldn’t manage to grasp was the mind-set of the boni, which seemed to him so utterly stupid that it beggared understanding. No use in telling himself, either, that if only he had relented a little in his compulsion to show up their ridiculous inadequacies, they might perhaps have been less determined to tear him down. Caesar had a temper, and Caesar did not suffer fools gladly.

Bibulus. He had been the start of it, at Lucullus’s siege of Mitylene on the island of Lesbos, thirty-three years ago. Bibulus. So small and so soaked in malice that Caesar had lifted him bodily on to the top of a high closet, laughed at him and made him a figure of fun to their fellows.

Lucullus. Lucullus the commander at Mitylene. Who implied that Caesar had obtained a fleet of ships from the decrepit old King of Bithynia by prostituting himself—an accusation the boni had revived years later and used in the Forum Romanum as part of their political smear campaign. Other men ate feces and violated their daughters, but Caesar had sold his arse to King Nicomedes to obtain a fleet. Only time and some sensible advice from his mother had worn the accusation out from sheer lack of evidence. Lucullus, whose vices were disgusting. Lucullus, the intimate of Lucius Cornelius Sulla.

Sulla, who while Dictator had freed Caesar from that hideous priesthood Gaius Marius had inflicted on him at thirteen years of age—a priesthood that forbade him to don weapons of war or witness death. Sulla had freed him to spite the dead Marius, then sent him east, aged nineteen, mounted on a mule, to serve with Lucullus at Mitylene. Where Caesar had not endeared himself to Lucullus. When the battle came on, Lucullus had thrown Caesar to the arrows, except that Caesar walked out of it with the corona civica, the oak-leaf crown awarded for the most conspicuous bravery, so rarely won that its winner was entitled to wear the crown forever after on every public occasion, and have all and sundry rise to their feet to applaud him. How Bibulus had hated having to rise to his feet and applaud Caesar every time the Senate met! The oak-leaf crown had also entitled Caesar to enter the Senate, though he was only twenty years old; other men had to wait until they turned thirty. However, Caesar had already been a senator; the special priest of Jupiter Optimus Maximus was automatically a senator, and Caesar had been that until Sulla freed him. Which meant that Caesar had been a senator for thirty-eight of his fifty-two years of life.

Caesar’s ambition had been to attain every political office at the correct age for a patrician and at the top of the poll—without bribing. Well, he couldn’t have bribed; the boni would have pounced on him in an instant. He had achieved his ambition, as was obligatory for a Julian directly descended from the goddess Venus through her son, Aeneas. Not to mention a Julian directly descended from the god Mars through his son, Romulus, the founder of Rome. Mars: Ares, Venus: Aphrodite.

Though it was now six nundinae in the past, Caesar could still put himself back in Ephesus gazing at the statue of himself erected in the agora, and at its inscription: GAIUS JULIUS CAESAR, SON OF GAIUS, PONTIFEX MAXIMUS, IMPERATOR, CONSUL FOR THE SECOND TIME, DESCENDED FROM ARES AND APHRODITE, GOD MADE MANIFEST AND COMMON SAVIOR OF MANKIND. Naturally there had been statues of Pompey the Great in every agora between Olisippo and Damascus (all torn down as soon as he lost at Pharsalus), but none that could claim descent from any god, let alone Ares and Aphrodite. Oh, every statue of a Roman conqueror said things like GOD MADE MANIFEST AND COMMON SAVIOR OF MANKIND! To an eastern mentality, standard laudatory stuff. But what truly mattered to Caesar was ancestry, and ancestry was something that Pompey the Gaul from Picenum could never claim; his sole notable ancestor was Picus, the woodpecker totem. Yet there was Caesar’s statue describing his ancestry for all of Ephesus to see. Yes, it mattered.

Caesar scarcely remembered his father, always absent on some duty or other for Gaius Marius, then dead when he bent to lace up his boot. Such an odd way to die, lacing up a boot. Thus had Caesar become paterfamilias at fifteen. It had been Mater, an Aurelia of the Cottae, who was both father and mother—strict, critical, stern, unsympathetic, but stuffed with sensible advice. For senatorial stock, the Julian family had been desperately poor, barely hanging on to enough money to satisfy the censors; Aurelia’s dowry had been an insula apartment building in the Subura, one of Rome’s most notorious stews, and there the family had lived until Caesar got himself elected Pontifex Maximus and could move into the Domus Publica, a minor palace owned by the State.

How Aurelia used to fret over his careless extravagance, his indifference to mountainous debt! And what dire straits insolvency had led him into! Then, when he conquered Long-haired Gaul, he had become even richer than Pompey the Great, if not as rich as Brutus. No Roman was as rich as Brutus, for in his Servilius Caepio guise he had fallen heir to the Gold of Tolosa. Which had made Brutus a very desirable match for Julia until Pompey the Great had fallen in love with her. Caesar had needed Pompey’s political clout more than young Brutus’s money, so…

Julia. All of my beloved women are dead, two of them trying to bear sons. Sweetest little Cinnilla, darling Julia, each just over the threshold of adult life. Neither ever caused me a single heartache save in their dying. Unfair, unfair! I close my eyes and there they are: Cinnilla, wife of my youth; Julia, my only daughter. The other Julia, Aunt Julia the wife of that awful old monster, Gaius Marius. Her perfume can still reduce me to tears when I smell it on some unknown woman. My childhood would have been loveless had it not been for her hugs and kisses. Mater, the perfect partisan adversary, was incapable of hugs and kisses for fear that overt love would corrupt me. She thought me too proud, too conscious of my intelligence, too prone to be royal.

But they are all gone, my beloved women. Now I am alone.

No wonder I begin to feel my age.

It was on the scales of the gods which one of them had had the harder time succeeding, Caesar or Sulla. Not much in it: a hair, a fibril. They had both been forced to preserve their dignitas—their personal share of public fame, of standing and worth—by marching on Rome. They had both been made Dictator, the sole office above democratic process or future prosecution. The difference between them lay in how they had behaved once appointed Dictator: Sulla had proscribed, filled the empty Treasury by killing wealthy senators and knight-businessmen and confiscating their estates; Caesar had preferred clemency, was forgiving his enemies and allowing the majority of them to keep their property.

The boni had forced Caesar to march on Rome. Consciously, deliberately—even gleefully!—they had thrust Rome into civil war rather than accord Caesar one iota of what they had given to Pompey the Great freely. Namely, the right to stand for the consulship without needing to present himself in person inside the city. The moment a man holding imperium crossed the sacred boundary into the city, he lost that imperium and was liable to prosecution in the courts. And the boni had rigged the courts to convict Caesar of treason the moment he laid down his governor’s imperium in order to seek a second, perfectly legal, consulship. He had petitioned to be allowed to stand in absentia, a reasonable request, but the boni had blocked it and blocked all his overtures to reach an agreement. When all else had failed, he emulated Sulla and marched on Rome. Not to preserve his head; that had never been in danger. The sentence in a court stacked with boni minions would have been permanent exile, a far worse fate than death.

Treason? To pass laws that distributed Rome’s public lands more equitably? Treason? To pass laws that prevented governors from looting their provinces? Treason? To push the boundaries of the Roman world back to a natural frontier along the Rhenus River and thus preserve Italy and Our Sea from the Germans? These were treasonous? In passing these laws, in doing these things, Caesar had betrayed his country?

To the boni, yes, he had. Why? How could that be? Because to the boni such laws and actions were an offense against the mos maiorum—the way custom and tradition said Rome worked. His laws and actions changed what Rome always had been. No matter that the changes were for the common good, for Rome’s security, for the happiness and prosperity not only of all Romans, but of Rome’s provincial subjects too: they were not laws and actions in keeping with the old ways, the ways that had been appropriate for a tiny city athwart the salt routes of central Italy six hundred years ago. Why was it that the boni couldn’t see that the old ways were no longer of use to the sole great power west of the Euphrates River? Rome had inherited the entire western world, yet some of the men who governed her still lived in the time of the infant city-state.

To the boni, change was the enemy, and Caesar was the enemy’s most brilliant servant ever. As Cato used to shout from the rostra in the Forum Romanum, Caesar was the human embodiment of pure evil. All because Caesar’s mind was clear enough and acute enough to know that unless change of the right kind came, Rome would die, molder away to stinking tatters only fit for a leper.

So here on this ship stood Caesar Dictator, the ruler of the world. He, who had never wanted anything more than his due—to be legally elected consul for the second time ten years after his first consulship, as the lex Genucia prescribed. Then, after that second consulship, he had planned to become an elder statesman more sensible and efficacious than that vacillating, timorous mouse, Cicero. Accept a senatorial commission from time to time to lead an army in Rome’s service as only Caesar could lead an army. But to end in ruling the world? That was a tragedy worthy of Aeschylus or Sophocles.

Most of Caesar’s foreign service had been spent at the western end of Our Sea—the Spains, the Gauls. His service in the east had been limited to Asia Province and Cilicia, had never led him to Syria or Egypt or the awesome interior of Anatolia.

The closest he had come to Egypt was Cyprus, years before Cato had annexed it; it had been ruled then by Ptolemy the Cyprian, the younger brother of the then ruler of Egypt, Ptolemy Auletes. In Cyprus he had dallied in the arms of a daughter of Mithridates the Great, and bathed in the sea foam from which his ancestress Venus/ Aphrodite had been born. The elder sister of this Mithridatid lady had been Cleopatra Tryphaena, first wife of King Ptolemy Auletes of Egypt, and mother of the present Queen Cleopatra.

He had had dealings with Ptolemy Auletes when he had been senior consul eleven years ago, and thought now of Auletes with wry affection. Auletes had desperately needed to have Rome confirm his tenure of the Egyptian throne, and wanted “Friend and Ally of the Roman People” status as well. Caesar the senior consul had been pleased to legislate him both, in return for six thousand talents of gold. A thousand of those talents had gone to Pompey and a thousand more to Marcus Crassus, but the four thousand left had enabled Caesar to do what the Senate had refused him the funds to do—recruit and equip the necessary number of legions to conquer Gaul and contain the Germans.

Oh, Marcus Crassus! How he had lusted after Egypt! He had deemed it the richest land on the globe, awash with gold and precious stones. Insatiably hungry for wealth, Crassus had been a mine of information about Egypt, which he wanted to annex into the Roman fold. What foiled him were the Eighteen, the upper stratum of Rome’s commercial world, who had seen immediately that Crassus and Crassus alone would benefit from the annexation of Egypt. The Senate might delude itself that it controlled Rome’s government, but the knight-businessmen of the Eighteen senior Centuries did that. Rome was first and foremost an economic entity devoted to business on an international scale.

So in the end Crassus had set out to find his gold mountains and jewel hills in Mesopotamia, and died at Carrhae. The King of the Parthians still possessed seven Roman Eagles captured from Crassus at Carrhae. One day, Caesar knew, he would have to march to Ecbatana and wrest them off the Parthian king. Which would constitute yet another huge change; if Rome absorbed the Kingdom of the Parthians, she would rule East as well as West.

The distant view of a sparkling white tower brought him out of his reverie to stand watching raptly as it drew closer. The fabled lighthouse of Pharos, the island which lay across the seaward side of Alexandria’s two harbors. Made of three hexagonal sections, each smaller in girth than the one below, and covered in white marble, the lighthouse stood three hundred feet tall and was a wonder of the world. On its top there burned a perpetual fire reflected far out to sea in all directions by an ingenious arrangement of highly polished marble slabs, though during daylight the fire was almost invisible. Caesar had read all about it, knew that it was those selfsame marble slabs shielded the flames from the winds, but he burned to ascend the six hundred stairs and look.

“It is a good day to enter the Great Harbor,” said his pilot, a Greek mariner who had been to Alexandria many times. “We will have no trouble seeing the channel markers—anchored pieces of cork painted red on the left and yellow on the right.”

Caesar knew all that too, though he tilted his head to gaze at the pilot courteously and listened as if he knew nothing.

“There are three channels—Steganos, Poseideos and Tauros, from left to right as you come in from the sea. Steganos is named after the Hog’s Back Rocks, which lie off the end of Cape Lochias where the palaces are—Poseideos is so named because it looks directly at Poseidon’s temple—and Tauros is named after the Bull’s Horn Rock which lies off Pharos Isle. In a storm—luckily they are rare hereabouts—it is impossible to enter either harbor. We foreign pilots avoid the Eunostus Harbor—drifting sandbanks and shoals everywhere. As you can see,” he chattered on, waving his hand about, “the reefs and rocks abound for miles outside. The lighthouse is a boon for foreign ships, and they say it cost eight hundred gold talents to build.”

Caesar was using his legionaries to row: it was good exercise and kept the men from growing sour and quarrelsome. No Roman soldier liked being separated from terra firma, and most would spend an entire voyage managing not to look over the ship’s side into the water. Who knew what lurked thereunder?

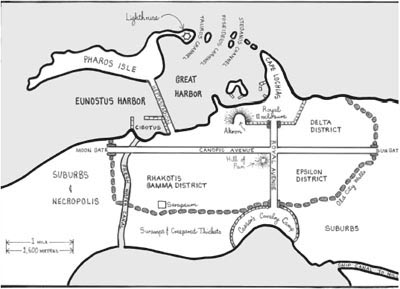

The pilot decided that all of Caesar’s ships would use the Poseideos passage, as today it was the calmest of the three. Standing at the prow alone, Caesar took in the sights. A blaze of colors, of golden statues and chariots atop building pediments, of brilliant whitewash, of trees and palms; but disappointingly flat save for a verdant cone two hundred feet tall and a rocky semi-circle on the shoreline just high enough to form the cavea of a large theater. In older days, he knew, the theater had been a fortress, the Akron, which meant “rock.”

The city to the left of the theater looked enormously richer and grander—the Royal Enclosure, he decided; a vast complex of palaces set on high daises of shallow steps, interspersed with gardens and groves of trees or palms. Beyond the theater citadel the wharves and warehouses began, sweeping in a curve to the right until they met the beginning of the Heptastadion, an almost mile-long white marble causeway that linked Pharos Isle to the land. It was a solid structure except for two large archways under its middle regions, each big enough to permit the passage of a sizable ship between this harbor, the Great Harbor, and the western one, the Eunostus Harbor. Was the Eunostus where Pompey’s ships were moored? No sign of them on this side of the Heptastadion.

Because of the flatness it was impossible to gauge Alexandria’s dimensions beyond its waterfront, but he knew that if the urban sprawl outside the old city walls were included, Alexandria held three million people and was the largest city in the world. Rome held a million within her Servian Walls, Antioch more, but neither could rival Alexandria, a city less than three hundred years old.

Suddenly came a flurry of activity ashore, followed by the appearance of about forty warships, all manned with armed men. Oh, well done! thought Caesar. From peace to war in a quarter of an hour. Some of the warships were massive quinqueremes with great bronze beaks slicing the water at their bows, some were quadriremes and triremes, all beaked, but about half were much smaller, cut too low to the water to venture out to sea—the customs vessels that patrolled the seven mouths of river Nilus, he fancied. They had sighted none on their way south, but that was not to say that sharp eyes atop some lofty Delta tree hadn’t spied this Roman fleet. Which would account for such readiness.

Hmmm. Quite a reception committee. Caesar had the bugler blow a call to arms, then followed that with a series of flags that told his ship’s captains to stand and wait for further orders. He had his servant drape his toga praetexta about him, put his corona civica on his thinning pale gold hair, and donned his maroon senatorial shoes with the silver crescent buckles denoting a senior curule magistrate. Ready, he stood amidships at the break in the rail and watched the rapid approach of an undecked customs boat, a fierce fellow standing in its bows.

“What gives you the right to enter Alexandria, Roman?” the fellow shouted, keeping his vessel at a hailing distance.

“The right of any man who comes in peace to buy water and provisions!” Caesar called, mouth twitching.

“There’s a spring seven miles west of the Eunostus Harbor—you can find water there! We have no provisions to sell, so be on your way, Roman!”

“I’m afraid I can’t do that, my good man.”

“Do you want a war? You’re outnumbered already, and these are but a tenth of what we can launch!”

“I have had my fill of wars, but if you insist, then I’ll fight another one,” Caesar said. “You’ve put on a fine show, but there are at least fifty ways I could roll you up, even without any warships. I am Gaius Julius Caesar Dictator.”

The aggressive fellow chewed his lip. “All right, you can go ashore yourself, whoever you are, but your ships stay right here in the harbor roads, understood?”

“I need a pinnace able to hold twenty-five men,” Caesar called.

“It had better be forthcoming at once, my man, or there will be big trouble.”

A grin dawned; the aggressive fellow rapped an order at his oarsmen and the little ship skimmed away.

Publius Rufrius appeared at Caesar’s shoulder, looking very anxious. “They seem to have plenty of marines,” he said, “but the farsighted among us haven’t been able to detect any soldiers ashore, apart from some pretty fellows behind the palace area wall—the Royal Guard, I imagine. What do you intend to do, Caesar?”

“Go ashore with my lictors in the boat they provide.”

“Let me lower our own boats and send some troops with you.”

“Certainly not,” Caesar said calmly. “Your duty is to keep our ships together and out of harm’s way—and stop ineptes like Tiberius Nero from chopping off his foot with his own sword.”

Shortly thereafter a large pinnace manned by sixteen oarsmen hove alongside. Caesar’s eyes roamed across the outfits of his lictors, still led by the faithful Fabius, as they tumbled down to fill up the board seats. Yes, every brass boss on their broad black leather belts was bright and shiny, every crimson tunic was clean and minus creases, every pair of crimson leather caligae properly laced. They cradled their fasces more gently and reverently than a cat carried her kittens; the crisscrossed red leather thongs were exactly as they should be, and the single-headed axes, one to a bundle, glittered wickedly between the thirty red-dyed rods that made up each bundle. Satisfied, Caesar leaped as lightly as a boy into the craft and disposed himself neatly in the stern.

The pinnace headed for a jetty adjacent to the Akron theater but outside the wall of the Royal Enclosure. Here a crowd of what seemed ordinary citizens had collected, waving their fists and shouting threats of murder in Macedonian-accented Greek. When the boat tied up and the lictors climbed out the citizens backed away a little, obviously taken aback at such calmness, such alien but impressive splendor. Once his twenty-four lictors had lined up in a column of twelve pairs, Caesar made light work of getting out himself, then stood arranging the folds of his toga fussily. Brows raised, he stared haughtily at the crowd, still shouting murder.

“Who’s in charge?” he asked it.

No one, it seemed.

“On, Fabius, on!”

His lictors walked into the middle of the crowd, with Caesar strolling in their wake. Just verbal aggression, he thought, smiling aloofly to right and left. Interesting. Hearsay is true, the Alexandrians don’t like Romans. Where is Pompeius Magnus?

A striking gate stood in the Royal Enclosure wall, its pylon sides joined by a square-cut lintel; it was heavily gilded and bright with many colors, strange, flat, two-dimensional scenes and symbols. Here further progress was rendered impossible by a detachment of the Royal Guard. Rufrius was right, they were very pretty in their Greek hoplite armor of linen corselets oversewn with silver metal scales, gaudy purple tunics, high brown boots, silver nose-pieced helmets bearing purple horsehair plumes. They also looked, thought an intrigued Caesar, as if they knew how to conduct themselves in a scrap rather than a battle. Considering the history of the royal House of Ptolemy, probably true. There was always an Alexandrian mob out to change one Ptolemy for another Ptolemy, sex not an issue.

“Halt!” said the captain, a hand on his sword hilt.

Caesar approached through an aisle of lictors and came to an obedient halt. “I would like to see the King and Queen,” he said.

“Well, you can’t see the King and Queen, Roman, and that is that. Now get back on board your ship and sail away.”

“Tell their royal majesties that I am Gaius Julius Caesar.”

The captain made a rude noise. “Ha ha ha! If you’re Caesar, then I’m Taweret, the hippopotamus goddess!” he sneered.

“You ought not to take the names of your gods in vain.”

A blink. “I’m not a filthy Egyptian, I’m an Alexandrian! My god is Serapis. Now go on, be off with you!”

“I am Caesar.”

“Caesar’s in Asia Minor or Anatolia or whatever.”

“Caesar is in Alexandria, and asking very politely to see the King and Queen.”

“Um—I don’t believe you.”

“Um—you had better, Captain, or else the full wrath of Rome will fall upon Alexandria and you won’t have a job. Nor will the King and Queen. Look at my lictors, you fool! If you can count, then count them, you fool! Twenty-four, isn’t that right? And which Roman curule magistrate is preceded by twenty-four lictors? One only—the dictator. Now let me through and escort me to the royal audience chamber,” Caesar said pleasantly.

Beneath his bluster the captain was afraid. What a situation to be in! No one knew better than he that there was no one in the palace who ought to be in the palace—no King, no Queen, no Lord High Chamberlain. Not a soul with the authority to see and deal with this up-himself Roman who did indeed have twenty-four lictors. Could he be Caesar? Surely not! Why would Caesar be in Alexandria, of all places? Yet here definitely stood a Roman with twenty-four lictors, clad in a ludicrous purple-bordered white blanket, with some leaves on his head and a plain cylinder of ivory resting on his bare right forearm between his cupped hand and the crook of his elbow. No sword, no armor, not a soldier in sight.

Macedonian ancestry and a wealthy father had bought the captain his position, but mental acuity was not a part of the package. Yet, yet—he licked his lips. “All right, Roman, to the audience room it is,” he said with a sigh. “Only I don’t know what you’re going to do when you get there, because there’s nobody home.”

“Indeed?” asked Caesar, beginning to walk behind his lictors again, which forced the captain to send a man running on ahead to guide the party. “Where is everybody?”

“At Pelusium.”

“I see.”

Though it was summer, the day was perfect; low humidity, a cool breeze to fan the brow, a caressing balminess that carried a hint of perfume from gloriously flowering trees, nodding bell blooms of some strange plant below them. The paving was brown-streaked fawn marble and polished to a mirror finish—slippery as ice when it rains. Or does it rain in Alexandria? Perhaps it doesn’t.

“A delightful climate,” he remarked.

“The best in the world,” said the captain, sure of it.

“Am I the first Roman you’ve seen here lately?”

“The first announcing he’s higher than a governor, at any rate. The last Romans we had here were when Gnaeus Pompeius came last year to pinch warships and wheat off the Queen.” He chuckled reminiscently. “Rude sort of young chap, wouldn’t take no for an answer, though her majesty told him the country’s in famine. Oh, she diddled him! Filled up sixty cargo ships with dates.”

“Dates?”

“Dates. He sailed off thinking the holds were full of wheat.”

“Dear me, poor young Gnaeus Pompeius. I imagine his father was not at all pleased, though Lentulus Crus might have been—Epicures love a new taste thrill.”

The audience chamber stood in a building of its own, if size was anything to go by; perhaps an anteroom or two for the visiting ambassadors to rest in, but certainly not live in. It was the same place to which Gnaeus Pompey had been conducted: a huge bare hall with a polished marble floor in complicated patterns of different colors; walls either filled with those bright paintings of two-dimensional people and plants, or covered in gold leaf; a purple marble dais with two thrones upon it, one on the top tier in figured ebony and gilt, and a similar but smaller one on the next tier down; otherwise, not a stick of furniture to be seen.

Leaving Caesar and his lictors alone in the room, the captain hurried off, presumably to see who he could find to receive them.

Eyes meeting Fabius’s, Caesar grinned. “What a situation!”

“We’ve been in worse situations than this, Caesar.”

“Don’t tempt Fortuna, Fabius. I wonder what it feels like to sit upon a throne?”

Caesar bounded up the steps of the dais and sat gingerly in the magnificent chair on top, its gold, jewel-encrusted detail quite extraordinary at close quarters. What looked like an eye, except that its outer margin was extended and swelled into an odd, triangular tear; a cobra head; a scarab beetle; leopard paws; human feet; a peculiar key; stick-like symbols.

“Is it comfortable, Caesar?”

“No chair having a back can be comfortable for a man in a toga, which is why we sit in curule chairs,” Caesar answered. He relaxed and closed his eyes. “Camp on the floor,” he said after a while; “it seems we’re in for a long wait.”

Two of the younger lictors sighed in relief, but Fabius shook his head, scandalized. “Can’t do that, Caesar. It would look sloppy if someone came in and caught us.”

As there was no water clock, it was difficult to measure time, but to the younger lictors it seemed like hours that they stood in a semi-circle with their fasces grounded delicately between their feet, axed upper ends held between their hands. Caesar continued to sleep—one of his famous cat naps.

“Hey, get off the throne!” said a young female voice.

Caesar opened one eye, but didn’t move.

“I said, get off the throne!”

“Who is it commands me?” Caesar asked.

“The royal Princess Arsinoë of the House of Ptolemy!”

That straightened Caesar, though he didn’t get up, just looked with both eyes open at the speaker, now standing at the foot of the dais. Behind her stood a little boy and two men.

About fifteen years old, Caesar judged: a busty, strapping girl with masses of golden hair, blue eyes, and a face that ought to have been pretty—it was regular enough of feature—but was not. Thanks to its expression, Caesar decided—arrogant, angry, quaintly authoritarian. She was clad in Greek style, but her robe was genuine Tyrian purple, a color so dark it seemed black, yet with the slightest movement was shot with highlights of plum and crimson. In her hair she wore a gem-studded coronet, around her neck a fabulous jeweled collar, bracelets galore on her bare arms; her earlobes were unduly long, probably due to the weight of the pendants dangling from them.

The little boy looked to be about nine or ten and was very like Princess Arsinoë—same face, same coloring, same build. He too wore Tyrian purple, a tunic and Greek chlamys cloak.

Both the men were clearly attendants of some kind, but the one standing protectively beside the boy was a feeble creature, whereas the other, closer to Arsinoë, was a person to be reckoned with. Tall, of splendid physique, quite as fair as the royal children, he had intelligent, calculating eyes and a firm mouth.

“And where do we go from here?” Caesar asked calmly.

“Nowhere until you prostrate yourself before me! In the absence of the King, I am regnant in Alexandria, and I command you to come down from there and abase yourself!” said Arsinoë. She looked at the lictors balefully. “All of you, on the floor!”

“Neither Caesar nor his lictors obey the commands of petty princelings,” Caesar said gently. “In the absence of the King, I am regnant in Alexandria by virtue of the terms of the wills of Ptolemy Alexander and your father Auletes.” He leaned forward. “Now, Princess, let us get down to business—and don’t look like a child in need of a spanking, or I might have one of my lictors pluck a rod from his bundle and administer it.” His gaze went to Arsinoë’s impassive attendant. “And you are?” he asked.

“Ganymedes, eunuch tutor and guardian of my Princess.”

“Well, Ganymedes, you look like a man of good sense, so I’ll address my comments to you.”

“You will address me!” Arsinoë yelled, face mottling. “And get down off the throne! Abase yourself!”

“Hold your tongue!” Caesar snapped. “Ganymedes, I require suitable accommodation for myself and my senior staff inside the Royal Enclosure, and sufficient fresh bread, green vegetables, oil, wine, eggs and water for my troops, who will remain on board my ships until I’ve discovered what’s going on here. It is a sad state of affairs when the Dictator of Rome arrives anywhere on the surface of this globe to unnecessary aggression and pointless inhospitality. Do you understand me?”

“Yes, great Caesar.”

“Good!” Caesar rose to his feet and walked down the steps. “The first thing you can do for me, however, is remove these two obnoxious children.”

“I cannot do that, Caesar, if you want me to remain here.”

“Why?”

“Dolichos is a whole man. He may remove Prince Ptolemy Philadelphus, but the Princess Arsinoë may not be in the company of a whole man unchaperoned.”

“Are there any more in your castrated state?” Caesar asked, mouth twitching; Alexandria was proving amusing.

“Of course.”

“Then go with the children, deposit Princess Arsinoë with some other eunuch, and return to me immediately.”

Princess Arsinoë, temporarily squashed by Caesar’s tone when he told her to hold her tongue, was getting ready to liberate it, but Ganymedes took her firmly by the shoulder and led her out, the boy Philadelphus and his tutor hurrying ahead.

“What a situation!” said Caesar to Fabius yet again.

“My hand itched to remove that rod, Caesar.”

“So did mine.” The Great Man sighed. “Still, from what one hears, the Ptolemaic brood is rather singular. At least Ganymedes is rational—but then, he’s not royal.”

“I thought eunuchs were fat and effeminate.”

“I believe that those who are castrated as small boys are, but if the testicles are not enucleated until after puberty has set in, that may not be the case.”

Ganymedes returned quickly, a smile pasted to his face. “I am at your service, great Caesar.”

“Ordinary Caesar will do nicely, thank you. Now why is the court at Pelusium?”

The eunuch looked surprised. “To fight the war,” he said.

“What war?”

“The war between the King and Queen, Caesar. Earlier in the year, famine forced the price of food up, and Alexandria blamed the Queen—the King is but thirteen years old—and rebelled.” Ganymedes looked grim. “There is no peace here, you see. The King is controlled by his tutor, Theodotus, and the Lord High Chamberlain, Potheinus. They’re ambitious men, you understand. Queen Cleopatra is their enemy.”

“I take it that she fled?”

“Yes, but south to Memphis and the Egyptian priests. The Queen is also Pharaoh.”

“Isn’t every Ptolemy on the throne also Pharaoh?”

“No, Caesar, far from it. The children’s father, Auletes, was never Pharaoh. He refused to placate the Egyptian priests, who have great influence over the native Egyptians of Nilus. Whereas Queen Cleopatra spent some of her childhood in Memphis with the priests. When she came to the throne they anointed her Pharaoh. King and Queen are Alexandrian titles, they have no weight at all in Egypt of the Nilus, which is proper Egypt.”

“So Queen Cleopatra, who is Pharaoh, fled to Memphis and the priests. Why not abroad from Alexandria, like her father when he was spilled from the throne?” Caesar asked, fascinated.

“When a Ptolemy flees abroad from Alexandria, he or she must depart penniless. There is no great treasure in Alexandria. The treasure vaults lie in Memphis, under the authority of the priests. So unless the Ptolemy is also Pharaoh—no money. Queen Cleopatra was given money in Memphis, and went to Syria to recruit an army. She has but recently returned with that army, and has gone to earth on the northern flank of Mount Casius outside Pelusium.”

Caesar frowned. “A mountain outside Pelusium? I didn’t think there were any until Sinai.”

“A very big sandhill, Caesar.”

“Ahah. Continue, please.”

“General Achillas brought the King’s army to the southern side of the mount, and is camped there. Not long ago, Potheinus and Theodotus accompanied the King and the war fleet to Pelusium. A battle was expected when I last heard,” said Ganymedes.

“So Egypt—or rather, Alexandria—is in the midst of a civil war,” said Caesar, beginning to pace. “Has there been no sign of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus in the vicinity?”

“Not that I know of, Caesar. Certainly he is not in Alexandria. Is it true, then, that you defeated him in Thessaly?”

“Oh, yes. Decisively. He left Cyprus some days ago, I had believed bound for Egypt.” No, Caesar thought, watching Ganymedes, this man is genuinely ignorant of the whereabouts of my old friend and adversary. Where is Pompeius, then? Did he perhaps utilize that spring seven miles west of the Eunostus Harbor and sail on to Cyrenaica without stopping? He stopped pacing. “Very well, it seems I stand in loco parentis for these ridiculous children and their squabble. Therefore you will send two couriers to Pelusium, one to see King Ptolemy, the other to see Queen Cleopatra. I require both sovereigns to present themselves here to me in their own palace. Is that clear?”

Ganymedes looked uncomfortable. “I foresee no difficulties with the King, Caesar, but it may not be possible for the Queen to come to Alexandria. One sight of her, and the mob will lynch her.” He lifted his lip in contempt. “The favorite sport of the Alexandrian mob is tearing an unpopular ruler to pieces with their bare hands. In the agora, which is very spacious.” He coughed. “I must add, Caesar, that for your own protection you would be wise to confine yourself and your senior staff to the Royal Enclosure. At the moment the mob is ruling.”

“Do what you can, Ganymedes. Now, if you don’t mind, I’d like to be conducted to my quarters. And you will make sure that my soldiers are properly victualed. Naturally I will pay for every drop and crumb. Even at inflated famine prices.”

* * *

“So,” said Caesar to Rufrius over a late dinner in his new quarters, “I am no closer to learning the fate of poor Magnus, but I fear for him. Ganymedes was in ignorance, though I don’t trust the fellow. If another eunuch, Potheinus, can aspire to rule through a juvenile Ptolemy, why not Ganymedes with Arsinoë?”

“They’ve certainly treated us shabbily,” Rufrius said as he looked about. “In palace terms, they’ve put us in a shack.” He grinned. “I keep him away from you, Caesar, but Tiberius Nero is most put out at having to share with another military tribune—not to mention that he expected to dine with you.”

“Why on earth would he want to dine with one of the least Epicurean noblemen in Rome? Oh, the gods preserve me from these insufferable aristocrats!”

Just as if, thought Rufrius, inwardly smiling, he were not himself insufferable or aristocratic. But the insufferable part of him isn’t connected to his antique origins. What he can’t say to me without insulting my birth is that he loathes having to employ an incompetent like Nero for no other reason than that he is a patrician Claudius. The obligations of nobility irk him.

For two more days the Roman fleet remained at anchor with the infantry still on board; pressured, the Interpreter had allowed the German cavalry to be ferried ashore with their horses and put into a good grazing camp outside the crumbling city walls on Lake Mareotis. The locals gave these extraordinary-looking barbarians a wide berth; they went almost naked, were tattooed, and wore their never-cut hair in a tortuous system of knots and rolls on top of their heads. Besides, they spoke not a word of Greek.

Ignoring Ganymedes’s warning to remain within the Royal Enclosure, Caesar poked and pried everywhere during those two days, escorted only by his lictors, indifferent to danger. In Alexandria, he discovered, lay marvels worthy of his personal attention—the lighthouse, the Heptastadion, the water and drainage systems, the naval dispositions, the buildings, the people.

The city itself occupied a narrow spit of limestone between the sea and a vast freshwater lake; less than two miles separated the sea from this boundless source of sweet water, eminently drinkable even at this summer season. Asking questions revealed that Lake Mareotis was fed from canals that linked it to the big westernmost mouth of Nilus, the Canopic Nilus; because Nilus rose in high summer rather than in early spring, Mareotis avoided the usual concomitants of river-fed lakes—stagnation, mosquitoes. One canal, twenty miles long, was wide enough to provide two lanes for barges and customs ships, and was always jammed with traffic.

A different, single canal came off Lake Mareotis at the Moon Gate end of the city; it terminated at the western harbor, though its waters did not intermingle with the sea, so any current in it was diffusive, not propulsive. A series of big bronze sluice gates were inserted in its walls, raised and lowered by a system of pulleys from ox-driven capstans. The city’s water supply was drawn out of the canal through gently sloping pipes, each district’s inlet equipped with a sluice gate. Other sluice gates spanned the canal from side to side and could be closed off to permit the dredging of silt from its bottom.

One of the first things Caesar did was to climb the verdant cone called the Paneium, an artificial hill built of stones tamped down with earth and planted with lush gardens, shrubs, low palms. A paved spiral road wound up to its apex, and man-made streamlets with occasional waterfalls tumbled to a drain at its base. From the apex it was possible to see for miles, everything was so flat.

The city was laid out on a rectangular grid and had no back lanes or alleys. Every street was wide, but two were far wider than any roads Caesar had ever seen—over a hundred feet from gutter to gutter. Canopic Avenue ran from the Sun Gate at the eastern end of the city to the Moon Gate at the western end; Royal Avenue ran from the gate in the Royal Enclosure wall south to the old walls. The world-famous museum library lay inside the Royal Enclosure, but the other major public buildings were situated at the intersection of the two avenues—the agora, the gymnasium, the courts of justice, the Paneium or Hill of Pan.

Rome’s districts were logical, in that they were named after the hills upon which they sprawled, or the valleys between; in flat Alexandria the persnickety Macedonian founders had divided the place up into five arbitrary districts—Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta and Epsilon. The Royal Enclosure lay within Beta District; east of it was not Gamma, but Delta District, the home of hundreds of thousands of Jews who spilled south into Epsilon, which they shared with many thousands of Metics—foreigners with rights of residence rather than citizenship. Alpha was the commercial area of the two harbors, and Gamma, in the southwest, was also known as Rhakotis, the name of the village pre-dating Alexandria’s genesis.

Most who lived inside the old walls were at best modestly well off. The wealthiest in the population, all pure Macedonians, lived in beautiful garden suburbs west of the Moon Gate outside the walls, scattered between a vast necropolis set in parklands. Wealthy foreigners like Roman merchants lived outside the walls east of the Sun Gate. Stratification, thought Caesar: no matter where I look, I see stratification.

Social stratification was extreme and absolutely rigid—no New Men for Alexandria!

In this place of three million souls, only three hundred thousand held the Alexandrian citizenship: these were the pure-blood descendants of the original Macedonian army settlers, and they guarded their privileges ruthlessly. The Interpreter, who was the highest official, had to be of pure Macedonian stock; so did the Recorder, the Chief Judge, the Accountant, the Night Commander. In fact, all the highest offices, commercial as well as public, belonged to the Macedonians. The layers beneath were stepped by blood too: hybrid Macedonian Greeks, then plain Greeks, then the Jews and Metics, with the hybrid Egyptian Greeks (who were a servant class) at the very bottom. One of the reasons for this, Caesar learned, lay in the food supply. Alexandria did not publicly subsidize food for its poor, as Rome had always done, and was doing more and more. No doubt this was why the Alexandrians were so aggressive, and why the mob had such power. Panem et circenses is an excellent policy. Keep the poor fed and entertained, and they do not rise. How blind these eastern rulers are!

Two social facts fascinated Caesar most of all. One was that native Egyptians were forbidden to live in Alexandria. The other was even more bizarre. A highborn Macedonian father would deliberately castrate his cleverest, most promising son in order to qualify the adolescent boy for employment in the palace, where he had a chance to rise to the highest job of all, Lord High Chamberlain. To have a relative in the palace was tantamount to having the ear of the King and Queen. Much though the Alexandrians despise Egyptians, thought Caesar, they have absorbed so many Egyptian customs that what exists here today is the most curious muddle of East and West anywhere in the world.

Not all his time was devoted to such musings. Ignoring the growls and menacing faces, Caesar inspected the city’s military installations minutely, storing every fact in his phenomenal memory. One never knew when one might need these facts. Defense was maritime, not terrestrial. Clearly modern Alexandria feared no land invasions; invasion if it came would be from the sea, and undoubtedly Roman.

Tucked in the bottom eastern corner of the western, Eunostus, harbor, was the Cibotus—the Box—a heavily fortified inner harbor fenced off by walls as thick as those at Rhodes, its entrance barred by formidably massive chains. It was surrounded by ship sheds and bristled with artillery; room for fifty or sixty big war galleys in the sheds, Caesar judged. Not that the Cibotus sheds were the only ones; more lay around Eunostus itself.

All of which made Alexandria unique, a stunning blend of physical beauty and ingenious functional engineering. But it was not perfect. It had its fair share of slums and crime, the wide streets in the poorer Gamma-Rhakotis and Epsilon Districts were piled high with rotting refuse and animal corpses, and once away from the two avenues there was a dearth of public fountains and communal latrines. And absolutely no bathhouses.

There was also a local insanity. Birds! Ibises. Of two kinds, the white and the black, they were sacred. To kill one was unthinkable; if an ignorant foreigner did, he was dragged off to the agora to be torn into little pieces. Well aware of their sacrosanctity, the ibises exploited it shamelessly.

At the time Caesar arrived they were in residence, for they fled the summer rains in far off Aethiopia. This meant that they could fly superbly, but once in Alexandria, they didn’t. Instead, they stood around in literal thousands upon thousands all over those wonderful roads, crowding the main intersections so densely that they looked like an extra layer of paving. Their copious, rather liquid droppings fouled every inch of any surface whereon people walked, and for all its civic pride, Alexandria seemed to employ no one to wash the mounting excreta away. Probably when the birds flew back to Aethiopia the city engaged in a massive cleanup, but in the meantime—! Traffic weaved and wobbled; carts had to hire an extra man to walk ahead and push the creatures aside. Within the Royal Enclosure a small army of slaves gathered up the ibises tenderly, put them into cages and then casually emptied the cages into the streets outside.

About the most one could say for them was that they gobbled up cockroaches, spiders, scorpions, beetles and snails, and picked through the scraps tossed out by fishmongers, butchers and pasty makers. Otherwise, thought Caesar, secretly grinning as his lictors cleared a path for him through the ibises, they are the biggest nuisances in all creation.

On the third day a lone “barge” arrived in the Great Harbor and was skillfully rowed to the Royal Harbor, a small enclosed area abutting on to Cape Lochias. Rufrius had sent word of its advent, so Caesar strolled to a vantage point from which he could see disembarkation perfectly, yet was not in close enough proximity to attract attention.

The barge was a floating pleasure palace of enormous size, all gold and purple; a huge, temple-like cabin stood abaft the mast, complete with a pillared portico.

A series of litters came down to the pier, each carried by six men matched for height and appearance; the King’s litter was gilded, gem-encrusted, curtained with Tyrian purple and adorned with a plume of fluffy purple feathers on each corner of its faience-tiled roof. His majesty was carried on interlocked arms from the temple-cabin to the litter and inserted inside with exquisite care; a fair, pouting, pretty lad just on the cusp of puberty. After the King came a tall fellow with mouse-brown curls and a finely featured, handsome face; Potheinus the Lord High Chamberlain, Caesar decided, for he wore purple, a nice shade somewhere between Tyrian and the gaudy magenta of the Royal Guard, and a heavy gold necklace of peculiar design. Then came a slight, effeminate and elderly man in a purple slightly inferior to Potheinus’s; his carmined lips and rouged cheeks sat garishly in a petulant face. Theodotus the tutor. Always good to see the opposition before they see you.

Caesar hurried back to his paltry accommodation and waited for the royal summons.

It came, but not for some time. Back to the audience chamber behind his lictors, to find the King seated not on the top throne but on the lower one. Interesting. His elder sister was absent, yet he did not feel qualified to occupy her chair. He wore the garb of Macedonian kings: Tyrian purple tunic, chlamys cloak, and a wide-brimmed Tyrian purple hat with the white ribbon of the diadem tied around its tall crown like a band.

The audience was extremely formal and very short. The King spoke as if by rote with his eyes fixed on Theodotus, after which Caesar found himself dismissed without an opportunity to state his business.

Potheinus followed him out.

“A word in private, great Caesar?”

“Caesar will do. My place or yours?”

“Mine, I think. I must apologize,” Potheinus went on in a oily voice as he walked beside Caesar and behind the lictors, “for the standard of your accommodation. A silly insult. That idiot Ganymedes should have put you in the guest palace.”

“Ganymedes, an idiot? I didn’t think so,” Caesar said.

“He has ideas above his station.”

“Ah.”

Potheinus possessed his own palace among that profusion of buildings, situated on Cape Lochias itself and having a fine view not of the Great Harbor but of the sea. Had the Lord High Chamberlain wished it, he might have walked out his back door and down to a little cove wherein he could paddle his pampered feet.

“Very nice,” Caesar said, sitting in a backless chair.

“May I offer you the wine of Samos or Chios?”

“Neither, thank you.”

“Spring water, then? Herbal tea?”

“No.”

Potheinus seated himself opposite, his inscrutable grey eyes on Caesar. He may not be a king, but he bears himself like one. The face is weathered yet still beautiful, and the eyes are unsettling. Dauntingly intelligent eyes, cooler even than mine. He rules his feelings absolutely, and he is politic. If necessary, he will sit here all day waiting for me to make the opening move. Which suits me. I don’t mind moving first, it is my advantage.

“What brings you to Alexandria, Caesar?”

“Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus. I’m looking for him.”

Potheinus blinked, genuinely surprised. “Looking in person for a defeated enemy? Surely your legates could do that.”

“Surely they could, but I like to do my opponents honor, and there is no honor in a legate, Potheinus. Pompeius Magnus and I have been friends and colleagues these twenty-three years, and at one time he was my son-in-law. That we ended in choosing opposite sides in a civil war can’t alter what we are to each other.”

Potheinus’s face was losing color; he lifted his priceless goblet to his lips and drank as if his mouth had gone dry. “You may have been friends, but Pompeius Magnus is now your enemy.”

“Enemies come from alien cultures, Lord High Chamberlain, not from among the ranks of one’s own people. Adversary is a better word—a word allowing all the latitude things in common predicate. No, I don’t pursue Pompeius Magnus as an avenger,” Caesar said, not moving an inch, though somewhere inside him a cold lump was forming. “My policy,” he went on levelly, “has been clemency, and my policy will continue to be clemency. I’ve come to find Pompeius Magnus myself so that I can extend my hand to him in true friendship. It would be a poor thing to enter a Senate containing none but sycophants.”

“I do not understand,” Potheinus said, skin quite bleached. No, no, I cannot tell this man what we did in Pelusium! We mistook the matter, we have done the unforgivable. The fate of Pompeius Magnus will have to remain our secret. Theodotus! I must find an excuse to leave here and head him off!

But it was not to be. Theodotus bustled in like a housewife, followed closely by two kilt-clad slaves bearing a big jar between them. They put it down and stood stiffly.

All Theodotus’s attention was fixed on Caesar, whom he eyed in obvious appreciation. “The great Gaius Julius Caesar!” he fluted. “Oh, what an honor! I am Theodotus, tutor to his royal majesty, and I bring you a gift, great Caesar.” He tittered. “In fact, I bring you two gifts!”

No answer from Caesar, who sat very straight, his right hand holding the ivory rod of his imperium just as it had all along, his left hand cuddling the folds of toga over his shoulder. The generous, slightly uptilted mouth, sensuous and humorous, had gone thin, and the eyes were two black-ringed pellets of ice.

Blithely unaware, Theodotus stepped forward and held out his hand; Caesar laid the rod in his lap and extended his to take the seal ring. A lion’s head, and around the outside of the mane the letters CN POMP MAG. He didn’t look at it, just closed his fingers on it until they clenched it, white-knuckled.

One of the servants lifted the jar’s lid while the other put a hand inside, fiddled for a moment, then lifted out Pompey’s head by its thatch of silver hair, gone dull from the natron, trickling steadily into the jar.

The face looked very peaceful, lids lowered over those vivid blue eyes that used to gaze around the Senate so innocently, so much the eyes of the spoiled child he was. The snub nose, the thin small mouth, the dented chin, the round Gallic face. It was all there, all perfectly preserved, though the slightly freckled skin had gone grey and leathery.

“Who did this?” Caesar asked of Potheinus.

“Why, we did, of course!” Theodotus cried, and looked impish, delighted with himself. “As I said to Potheinus, dead men do not bite. We have removed your enemy, great Caesar. In fact, we have removed two of your enemies! The day after this one came, the great Lentulus Crus arrived, so we killed him too. Though we didn’t think you’d want to see his head.”

Caesar rose without a word and strode to the door, opened it and snapped, “Fabius! Cornelius!”

The two lictors entered immediately; only the rigorous training of years disciplined their reaction as they beheld the face of Pompey the Great, running natron.

“A towel!” Caesar demanded of Theodotus, and took the head from the servant who held it. “Get me a towel! A purple one!”

But it was Potheinus who moved, clicked his fingers at a bewildered slave. “You heard. A purple towel. At once.”

Finally realizing that the great Caesar was not pleased, Theodotus gaped at him in astonishment. “But, Caesar, we have eliminated your enemy!” he cried. “Dead men do not bite.”

Caesar spoke softly. “Keep your tongue between your teeth, you mincing pansy! What do you know of Rome or Romans? What kind of men are you, to do this?” He looked down at the dripping head, his eyes tearless. “Oh, Magnus, would that our destinies were reversed!” He turned to Potheinus. “Where is his body?”

The damage was done; Potheinus decided to brazen it out. “I have no idea. It was left on the beach at Pelusium.”

“Then find it, you castrated freak, or I’ll tear Alexandria down around your empty scrotum! No wonder this place festers, when creatures like you run things! You don’t deserve to live, either of you—nor does your puppet king! Tread softly, or count your days.”

“I would remind you, Caesar, that you are our guest—and that you do not have sufficient troops with you to attack us.”

“I am not your guest, I am your sovereign. Rome’s Vestal Virgins still hold the will of the last legitimate king of Egypt, Ptolemy XI, and I hold the will of the late King Ptolemy XII,” Caesar said. “Therefore I will assume the reins of government until I have adjudicated in this present situation, and whatever I decide will be adhered to. Move my belongings to the guest palace, and bring my infantry ashore today. I want them in a good camp inside the city walls. Do you think I can’t level Alexandria to the ground with what men I have? Think again!”

The towel arrived, Tyrian purple. Fabius took it and spread it between his hands in a cradle. Caesar kissed Pompey’s brow, then put the head in the towel and reverently wrapped it up. When Fabius went to take it, Caesar handed him the ivory rod of imperium instead.

“No, I will carry him.” At the door he turned. “I want a small pyre constructed in the grounds outside the guest palace. I want frankincense and myrrh to fuel it. And find the body!”

He wept for hours, hugging the Tyrian purple bundle, and no one dared to disturb him. Finally Rufrius came bearing a lamp—it was very dark—to tell him that everything had been moved to the guest palace, so please would he come too? He had to help Caesar up as if he were an old man and guide his footsteps through the grounds, lit with oil lamps inside Alexandrian glass globes.

“Oh, Rufrius! That it should have come to this!”

“I know, Caesar. But there is a little good news. A man has arrived from Pelusium, Pompeius Magnus’s freedman Philip. He has the ashes of the body, which he burned on the beach after the assassins rowed away. Because he carried Pompeius Magnus’s purse, he was able to travel across the Delta very quickly.”

So from Philip Caesar heard the full story of what had happened in Pelusium, and of the flight of Cornelia Metella and Sextus, Pompey’s wife and younger son.

In the morning, with Caesar officiating, they burned Pompey the Great’s head and added its ashes to the rest, enclosed them in a solid gold urn encrusted with red carbunculi and ocean pearls. Then Caesar put Philip and his poor dull slave aboard a merchantman heading west, bearing the ashes of Pompey the Great home to his widow. The ring, also entrusted to Philip, was to be sent on to the elder son, Gnaeus Pompey, wherever he might be.

All that done with, Caesar sent a servant to rent twenty-six horses and set out to inspect his dispositions. Which were, he soon discovered, disgraceful. Potheinus had located his 3,200 legionaries in Rhakotis on some disused land haunted by cats (also sacred animals) hunting myriad rats and mice, and, of course, already occupied by ibises. The local people, all poor hybrid Egyptian Greeks, were bitterly resentful both of the Roman camp in their midst and of the fact that famine-dogged Alexandria now had many extra mouths to feed. The Romans could afford to buy food, no matter what its price, but its price for the poor would spiral yet again because it had to stretch further.

“Well, we build a purely temporary wall and palisade around this camp, but we make it look as if we think it’s permanent. The natives are nasty, very nasty. Why? Because they’re hungry! On an income of twelve thousand gold talents a year, their wretched rulers don’t subsidize their food. This whole place is a perfect example of why Rome threw out her kings!” Caesar snorted, huffed. “Post sentries every few feet, Rufrius, and tell the men to add roast ibis to their diet. I piss on Alexandria’s sacred birds!”

Oh, he is in a temper! thought Rufrius wryly. How could those fools in the palace murder Pompeius Magnus and think to please Caesar? He’s wild with grief inside, and it won’t take much to push him into making a worse mess of Alexandria than he did of Uxellodunum or Cenabum. What’s more, the men haven’t been ashore a day yet, and they’re already lusting to kill the locals. There’s a mood building here, and a disaster brewing.

Since it wasn’t his place to voice any of this, he simply rode around with the Great Man and listened to him fulminate. It is more than grief putting him out so dreadfully. Those fools in the palace stripped him of the chance to act mercifully, draw Magnus back into our Roman fold. Magnus would have accepted. Cato, no, never. But Magnus, yes, always.

An inspection of the cavalry camp only made Caesar crankier. The Ubii Germans weren’t surrounded by the poor and there was plenty of good grazing, a clean lake to drink from, but there was no way that Caesar could use them in conjunction with his infantry, thanks to an impenetrably creepered swamp lying between them and the western end of the city, where the infantry lay. Potheinus, Ganymedes and the Interpreter had been cunning. But why, Rufrius asked himself in despair, do people irritate him? Every obstacle they throw in his path only makes him more determined—can they really delude themselves that they’re cleverer than Caesar? All those years in Gaul have endowed him with a strategic legacy so formidable that he’s equal to anything. But hold your tongue, Rufrius, ride around with him and watch him plan a campaign he may never need to conduct. But if he has to conduct it, he’ll be ready.

Caesar dismissed his lictors and sent Rufrius back to the Rhakotis camp armed with certain orders, then guided his horse up one street and down another, slowly enough to let the ibises stalk out from under the animal’s hooves, his eyes everywhere. At the intersection of Canopic and Royal Avenues he invaded the agora, a vast open space surrounded on all four sides by a wide arcade with a dark red back wall, and fronted by blue-painted Doric pillars. Next he went to the gymnasium, almost as large, similarly arcaded, but having hot baths, cold baths, an athletic track and exercise rings. In each he sat the horse oblivious to the glares of Alexandrians and ibises, then dismounted to examine the ceilings of the covered arcades and walkways. At the courts of justice he strolled inside, it seemed fascinated by the ceilings of its lofty rooms. From there he rode to the temple of Poseidon, thence to the Serapeum in Rhakotis, the latter a sanctuary to Serapis gifted with a huge temple amid gardens and other, smaller temples. Then it was off to the waterfront and its docks, its warehouses; the emporium, a gigantic trading center, received quite a lot of his attention, as did piers, jetties, quays curbed with big square wooden beams. Other temples and large public buildings along Canopic Avenue also interested him, particularly their ceilings, all held up by massive wooden beams. Finally he rode back down Royal Avenue to the German camp, there to issue instructions about fortifications.

“I’m sending you two thousand soldiers as additional labor to start dismantling the old city walls,” he told his legate. “You’ll use the stones to build two new walls, each commencing at the back of the first house on either side of Royal Avenue and fanning outward until you reach the lake. Four hundred feet wide at the Royal Avenue end, but five thousand feet wide at the lakefront. That will bring you hard against the swamp on the west, while your eastern wall will bisect the road to the ship canal between the lake and the Canopic Nilus. The western wall you’ll make thirty feet high—the swamp will provide additional defense. The eastern wall you’ll make twenty feet high, with a fifteen-foot-deep ditch outside mined with stimuli, and a water-filled moat beyond that. Leave a gap in the eastern wall to let traffic to the ship canal keep flowing, but have stones ready to close the gap the moment I so order you. Both walls are to have a watchtower every hundred feet, and I’ll send you ballistas to put on top of the eastern wall.”

Poker-faced, the legate listened, then went to find Arminius, the Ubian chieftain. Germans weren’t much use building walls, job would be to forage and stockpile fodder for the horses. They could also find wood for the fire-hardened, pointed stakes called stimuli, but their and start weaving withies for the breastworks—wonderful wicker weavers, Germans!

Back down Royal Avenue rode Caesar to the Royal Enclosure and an inspection of its twenty-foot-high wall, which ran from the crags of the Akron theater in a line that returned to the sea on the far side of Cape Lochias. Not a watchtower anywhere, and no real grasp of the defensive nature of a wall; far more effort and care had gone into its decoration. No wonder the mob stormed the Royal Enclosure so often! This wouldn’t keep an enterprising dwarf outside.

Time, time! It was going to take time, and he would have to fence and spar to fool people until his preparations were complete. First and foremost, there must be no indication apart from the activity at the cavalry camp that anything untoward was going on. Potheinus and his city minions like the Interpreter would assume that Caesar intended to huddle inside the cavalry fortress, abandon the city if attacked. Good. Let them think that.

When Rufrius returned from Rhakotis, he received more orders, after which Caesar summoned all his junior legates (including the hopeless Tiberius Claudius Nero) and led them through his plans. Of their discretion he had no doubts; this wasn’t Rome against Rome, this was war with a foreign power not one of them liked.

On the following day he summoned King Ptolemy, Potheinus, Theodotus and Ganymedes to the guest palace, where he seated them in chairs on the floor while he occupied his ivory curule chair on a dais. Which didn’t please the little king, though he allowed Theodotus to pacify him. That one has started sexual initiation, thought Caesar. What chance does the boy have, with such advisers? If he lives, he’ll be no better a ruler than his father was.

“I’ve called you here to speak about a subject I mentioned the day before yesterday,” Caesar said, a scroll in his lap. “Namely, the succession to the throne of Alexandria in Egypt, which I now understand is a somewhat different question from the throne of Egypt of the Nilus. Apparently the latter, King, is a position your absent sister enjoys, but you do not. To rule in Egypt of the Nilus, the sovereign must be Pharaoh. As is Queen Cleopatra. Why, King, is your co-ruler, sister and wife an exile commanding an army of mercenaries against her own subjects?”

Potheinus answered; Caesar had expected nothing else. The littleking did as he was told, and had insufficient intelligence to think without being led through the facts first. “Because her subjects rose up against her and ejected her, Caesar.”

“Why did they rise up against her?”

“Because of the famine,” Potheinus said. “Nilus has failed to inundate for two years in a row. Last year saw the lowest reading of the Nilometer since the priests started taking records three thousand years ago. Nilus rose only eight Roman feet.”

“Explain.”

“There are three kinds of inundation, Caesar. The Cubits of Death, the Cubits of Plenty, and the Cubits of Surfeit. To overflow its banks and inundate the valley, Nilus must rise eighteen Roman feet. Anything below that is in the Cubits of Death—water and silt will not be deposited on the land, so no crops can be planted. In Egypt, it never rains. Succor comes from Nilus. Readings between eighteen and thirty-two Roman feet constitute the Cubits of Plenty. Nilus floods enough to spread water and silt on all the growing land, and the crops come in. Inundations above thirty-two feet drown the valley so deeply that the villages are washed away and the waters do not recede in time to plant the crops,” Potheinus said as if by rote; evidently this was not the first time he had had to explain the inundation cycle to some ignorant foreigner.

“Nilometer?” Caesar asked.

“The device off which the inundation level is read. It is a well dug to one side of Nilus with the cubits marked on its wall. There are several, but the one of greatest importance is hundreds of miles to the south, at Elephantine on the First Cataract. There Nilus starts to rise one month before it does in Memphis, at the apex of the Delta. So we have warning what the year’s inundation is going to be like. A messenger brings the news down the river.”

“I see. However, Potheinus, the royal income is enormous. Don’t you use it to buy in grain when the crops don’t germinate?”

“Caesar must surely know,” said Potheinus smoothly, “that there has been drought all around Your Sea, from Spain to Syria. We have bought, but the cost is staggering, and naturally the cost must be passed on to the consumers.”

“Really? How sensible” was Caesar’s equally smooth reply. He lifted the scroll on his lap. “I found this in Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus’s tent after Pharsalus. It is the will of the twelfth Ptolemy, your father”—spoken to the lad, bored enough to doze—“and it is very clear. It directs that Alexandria and Egypt shall be jointly ruled by his eldest living daughter, Cleopatra, and his eldest son, Ptolemy Euergetes, as husband and wife.”

Potheinus had jumped. Now he reached out an imperious hand. “Let me see it!” he demanded. “If it were a true and legal will, it would reside either here in Alexandria with the Recorder, or with the Vestal Virgins in Rome.”

Theodotus had moved to stand behind the little king, fingers digging into his shoulder to keep him awake; Ganymedes sat, face impassive, listening. You, thought Caesar of Ganymedes, are the most able one. How it must irk you to suffer Potheinus as your superior! And, I suspect, you would far rather see your young Ptolemy, the Princess Arsinoë, sitting on the high throne. They all hate Cleopatra, but why?

“No, Lord High Chamberlain, you may not see it,” he said coldly. “In it, Ptolemy XII known as Auletes says that his will was not lodged either in Alexandria or Rome due to—er—‘embarrassments of the state.’ Since our civil war was far in the future when this document was drawn up, Auletes must have meant events here in Alexandria.” He straightened, face setting hard. “It is high time that Alexandria settled down, and that its rulers were more generous toward the lowly. I do not intend to depart this city until some consistent, humane conditions have been established for all its people, rather than its Macedonian citizens. I will not countenance festering sores of resistance to Rome in my wake, or permit any country to offer itself as a nucleus of further resistance to Rome. Accept the fact, gentlemen, that Caesar Dictator will remain in Alexandria to sort out its affairs—lance the boil, you might say. Therefore I sincerely hope that you have sent that courier to Queen Cleopatra, and that we see her here within a very few days.”

And that, he thought, is as close as I go to conveying the message that Caesar Dictator will not go away to leave Alexandria as a base for Republicans to use. They must all be shepherded to Africa Province, where I can stamp on them collectively.

He rose to his feet. “You are dismissed.”

They went, faces scowling.

“Did you send a courier to Cleopatra?” Ganymedes asked the Lord High Chamberlain as they emerged into the rose garden.

“I sent two,” said Potheinus, smiling, “but on a very slow boat. I also sent a third—on a very fast punt—to General Achillas, of course. When the two slow couriers emerge from the Delta at the Pelusiac mouth, Achillas will have men waiting. I am very much afraid”—he sighed—“that Cleopatra will receive no message from Caesar. Eventually he will turn on her, deeming her too arrogant to submit to Roman arbitration.”

“She has her spies in the palace,” Ganymedes said, eyes on the dwindling forms of Theodotus and the little king, hurrying ahead. “She’ll try to reach Caesar—it’s in her interests.”

“I am aware of that. But Captain Agathacles and his men are policing every inch of the wall and every wavelet on either side of Cape Lochias. She won’t get through my net.” Potheinus stopped to face the other eunuch, equally tall, equally handsome. “I take it, Ganymedes, that you would prefer Arsinoë as queen?”

“There are many who would prefer Arsinoë as queen,” said Ganymedes, unruffled. “Arsinoë herself, for example. And her brother the King. Cleopatra is tainted with Egypt, she’s poison.”

“Then,” said Potheinus, beginning to walk again, “I think it behooves both of us to work to that end. You can’t have my job, but if your own chargeling occupies the throne, that won’t really inconvenience you too much, will it?”

“No,” said Ganymedes, smiling. “What is Caesar up to?”

“Up to?”

“He’s up to something, I feel it in my bones. There’s a lot of activity at the cavalry camp, and I confess I’m surprised that he hasn’t begun to fortify his infantry camp in Rhakotis with anything like his reputed thoroughness.”

“What annoys me is his high-handedness!” Potheinus snapped tartly. “By the time he’s finished fortifying his cavalry camp, there won’t be a stone left in the old city walls.”

“Why,” asked Ganymedes, “do I think all this is a blind?”

The next day Caesar sent for Potheinus, no one else.

“I’ve a matter to broach with you on behalf of an old friend,” Caesar said, manner relaxed and expansive.

“Indeed?”

“Perhaps you remember Gaius Rabirius Postumus?”

Potheinus frowned. “Rabirius Postumus…Perhaps vaguely.”

“He arrived in Alexandria after the late Auletes had been put back on his throne. His purpose was to collect some forty million sesterces Auletes owed a consortium of Roman bankers, chief of whom was Rabirius. However, it seems the Accountant and all his splendid Macedonian public servants had allowed the city finances to get into a shocking state. So Auletes told my friend Rabirius that he would have to earn his money by tidying up both the royal and the public fiscus. Which Rabirius did, working night and day in Macedonian garments he found as repulsive as he did irksome. At the end of a year, Alexandria’s moneys were brilliantly organized. But when Rabirius asked for his forty million sesterces, Auletes and your predecessor stripped him as naked as a bird and threw him on a ship bound for Rome. Be thankful for your life, was their message. Rabirius arrived in Rome absolutely penniless. For a banker, Potheinus, a hideous fate.”

Grey eyes were locked with pale blue; neither man lowered his gaze. But a pulse was beating very fast in Potheinus’s neck.

“Luckily,” Caesar went on blandly, “I was able to assist my friend Rabirius get back on his financial feet, and today he is, with my other friends the Balbi Major and Minor, and Gaius Oppius, a veritable plutocrat of the plutocrats. However, a debt is a debt, and one of the reasons I decided to visit Alexandria concerns that debt. Behold in me, Lord High Chamberlain, Rabirius Postumus’s bailiff. Pay back the forty million sesterces at once. In international terms, they amount to one thousand six hundred talents of silver. Strictly speaking, I should demand interest on the sum at my fixed rate of ten percent, but I’m willing to forgo that. The principal will do nicely.”

“I am not authorized to pay the late king’s debts.”

“No, but the present king is.”

“The King is a minor.”

“Which is why I’m applying to you, my dear fellow. Pay up.”

“I shall need extensive documentation for proof.”

“My secretary Faberius will be pleased to furnish it.”

“Is that all, Caesar?” Potheinus asked, getting to his feet.

“For the moment.” Caesar strolled out with his guest, the personification of courtesy. “Any sign of the Queen yet?”

“Not a shadow, Caesar.”

Theodotus met Potheinus in the main palace, big with news. “Word from Achillas!” he said.

“I thank Serapis for that! He says?”

“That the couriers are dead, and that Cleopatra is still in her earth on Mount Casius. Achillas is sure she has no idea of Caesar’s presence in Alexandria, though what she’s going to make of Achillas’s next action is anyone’s guess. He’s moving twenty thousand foot and ten thousand horse by ship from Pelusium even as I speak. The Etesian winds have begun to blow, so he should be here in two days.” Theodotus chuckled gleefully. “Oh, what I would give to see Caesar’s face when Achillas arrives! He says he’ll use both harbors, but plans to make camp outside the Moon Gate.” Not a very observant man, he looked at the grim-faced Potheinus in sudden bewilderment. “Aren’t you pleased, Potheinus?”

“Yes, yes, that’s not what’s bothering me!” Potheinus snapped. “I’ve just seen Caesar, who dunned the royal purse for the money Auletes refused to pay the Roman banker, Rabirius Postumus. The hide! The temerity! After all these years! And I can’t ask the Interpreter to pay a private debt of the late king’s!”

“Oh, dear!”

“Well,” said Potheinus through his teeth, “I’ll pay Caesar the money, but he’ll rue the day he asked for it!”

“Trouble,” said Rufrius to Caesar the next day, the eighth since they had arrived in Alexandria.

“Of what kind?”