1

The Domus Publica had changed for the better on its exterior. Its ground floor was built of tufa blocks and had the old, rectangular windows, then Ahenobarbus Pontifex Maximus had added an opus incertum upper story faced with bricks and having arched windows. Caesar Pontifex Maximus added a temple pediment over the main entrance and gave the entire outside of the ugly building a more uniform look by facing it in polished marble. Inside it maintained its venerable beauty, for Caesar, Pontifex Maximus now for seventeen years, permitted no neglect.

Time, he thought, having finally returned from Sardinia, to start giving receptions, to suggest to Calpurnia that she host the Bona Dea celebrations in November; if Caesar Dictator was to be stranded in Rome for many months, he may as well create a splash.

His own quarters were on the ground floor; a bedroom and study, and, where his mother used to live, two offices for his chief secretary, Gaius Faberius. Who greeted him with slightly overdone pleasure, and wouldn’t meet his eyes.

“Are you so offended that I didn’t take you to Africa? I’d thought to give you a rest from travel, Faberius,” Caesar said.

Faberius jumped, shook his head. “No, Caesar, of course I wasn’t offended! I was able to get a great deal of work done in your absence, and see something of my family.”

“How are they?”

“Very happy to move to the Aventine. The Clivus Orbius has gone sadly downhill.”

“Orbian hill—downhill. Good pun,” said Caesar, and left it at that. But with a mental note to find out what was worrying this oldest among his secretaries.

When he entered his wife’s quarters upstairs he wished he had not, for Calpurnia had guests: Cato’s widow, Marcia, and Cato’s daughter, Porcia. Why did women choose peculiar friends? Still, it was too late to retreat now. Best to brazen it out. Calpurnia, he noticed, was growing into her beauty. At eighteen she had been a pleasant-looking girl, shy and quiet, and he knew perfectly well that her conduct during the years of his absence had been irreproachable. Now in her late twenties, she had a better figure, a great deal more composure, and was arranging her hair in a new, highly flattering style. His advent didn’t fluster her in the least, despite the vexation that being caught with these two women must have caused her.

“Caesar,” she said, rising and coming to kiss him lightly.

“Is that the same cat I gave you?” he asked, pointing to a rotund ball of reddish fur on a couch.

“Yes, that’s Felix. He’s getting old, but his health is good.”

Caesar had advanced to take Marcia’s hand and smile at Porcia in a friendly way.

“Ladies, a sad meeting. I would have given much to ensure a happier one.”

“I know,” said Marcia, blinking away tears. “Was he—was he well before—?”

“Very well, and much loved by all of Utica. So much so that the people of that city have given him a new cognomen—Uticensis. He was very brave,” said Caesar, making no attempt to sit.

“Naturally he was brave! He was Cato!” said Porcia in that same loud, harsh voice her father had owned.

How like him she was! A pity that she was the girl, young Marcus the boy. Though she would never have begged a pardon—would be fleeing to Spain, or dead.

“Are you living with Philippus?” he asked Marcia.

“For the time being,” she said, and sighed. “He wants me to marry again, but I don’t wish to.”

“If you don’t wish to, you shouldn’t. I’ll speak to him.”

“Oh yes, by all means do that!” Porcia snarled. “You’re the King of Rome, whatever you say must be obeyed!”

“No, I am not the King of Rome, nor do I want to be,” Caesar said quietly. “It was meant kindly, Porcia. How are you faring?”

“Since Marcus Brutus bought all Bibulus’s property, I live in Bibulus’s house with Bibulus’s youngest son.”

“I’m very glad that Brutus was so generous.” Taking in the sight of several more cats, Caesar used them as an excuse to bolt. “You’re lucky, Calpurnia. These creatures make my eyes water and my skin itch. Ave, ladies.”

And he escaped.

Faberius had put his important correspondence on his desk; frowning, he noted one scroll whose tag bore a date in May. Vatia Isauricus’s seal. Before he opened it, he knew it held bad news.

Syria is without a governor, Caesar. Your young cousin Sextus Julius Caesar is dead.

Did you by any chance meet a Quintus Caecilius Bassus when you passed through Antioch last year? In case you did not, I had better explain who he is. A Roman knight of the Eighteen, who took up residence in Tyre and went into the purple-dye business after serving with Pompeius Magnus during his eastern campaigns. He speaks fluent Median and Persian, and it is now being bandied about that he has friends at the court of the King of the Parthians. Certainly he is enormously rich, and not all his income is from Tyrian purple.

When you imposed those heavy penalties on Antioch and the cities of the Phoenician coast for so strongly supporting the Republicans, Bassus was gravely affected. He went to Antioch and looked up some old friends among the military tribunes of the Syrian legion, all men who had served with Pompeius Magnus. The next thing, governor Sextus Caesar was informed that you were dead in Africa Province and the Syrian legion was restive. He called the legion to an assembly intending to calm its men down, but they murdered him and hailed Bassus as their new commander.

Bassus then proclaimed himself the new governor of Syria, so all your clients and adherents in northern Syria fled at once to Cilicia. As I happened to be in Tarsus visiting Quintus Philippus, I was able to act swiftly, sent a letter to Marcus Lepidus in Rome, and asked him to send Syria a governor as quickly as possible. According to his reply, he has dispatched Quintus Cornificius, who should answer well. Cornificius and Vatinius fought a brilliant campaign in Illyricum last year.

However, Bassus has entrenched himself formidably. He marched to Antioch, which shut its gates and refused to let him in. So our friend the purple merchant marched down the road to Apameia: in return for many trade favors, it declared for Bassus, who entered it and has set himself up there, calling Apameia the capital of Syria.

He has worked a great deal of mischief, Caesar, and he is definitely in league with the Parthians. He’s made an alliance with the new king of the Skenite Arabs, one Alchaudonius—who, incidentally, was one of the Arabs with Abgarus when he led Marcus Crassus into the Parthian trap at Carrhae. Alchaudonius and Bassus are very busy recruiting troops for a new Syrian army. I imagine that the Parthians are going to invade, and that Bassus’s Syrian army will join them to move against Rome in Cilicia and Asia Province.

This means that both Quintus Philippus and I are also recruiting, and have sent warning to the client-kings.

Southern Syria is quiet. Your friend Antipater is making sure the Jews stay out of Bassus’s plans, and has sent to Queen Cleopatra in Egypt for men, armaments and food supplies against the day when the Parthians invade. The rebuilding and fortification of Jerusalem’s walls may turn out to be more vital than even you envisioned.

There have been Parthian raids up and down the Euphrates, though the territory of the Skenite Arabs has not suffered. You may have thought that the eastern end of Our Sea was pacified, but I doubt that Rome will ever be able to say that about any part of her world. There’s always someone lusting to take things off her.

Poor young Sextus Caesar, the grandson of his uncle, Sextus. That branch of the family—the elder branch—had had none of Caesar’s fabled luck. The patrician Julii Caesares used three first names—Sextus, Gaius and Lucius. If a Julius Caesar had three sons, the first was Sextus, the second Gaius, and the third Lucius. His own father was the second son, not the first, and only the marriage of his father’s elder sister to the fabulously wealthy New Man Gaius Marius had given his father the money to stay in the Senate and ascend the cursus honorum, the ladder to the senior magistracies. His father’s younger sister had married Sulla, so Caesar could rightly say that both Marius and Sulla were his uncles. Very handy through the years!

His father’s elder brother, Sextus, had died first, of a lung inflammation during a bitter winter campaign of the Italian civil war. Lungs! Suddenly Caesar remembered where he had previously seen the stigmata he had noticed in young Gaius Octavius. Uncle Sextus! He’d had the same look about him: the same narrow rib cage, small chest. There had not been a moment to ask Hapd’efan’e, and now he could offer the priest-physician more information. Uncle Sextus had suffered from the wheezes, used to go to the Fields of Fire behind Puteoli once a year to inhale the sulphur fumes that belched out of the earth amid splutters of lava and licks of flame. He remembered his father saying that the wheezes cropped up from time to time in a Julius Caesar, that it was a family trait. A family trait young Gaius Octavius had inherited? Was that why the lad didn’t attend the youths’ drills and exercises on the Campus Martius regularly?

Caesar summoned Hapd’ efan’e.

“Has Trogus given you a nice room, Hapd’efan’e?” he asked.

“Yes, Caesar. A beautiful guest suite that overlooks the big peristyle. I have the space to store my medicaments and my instruments, and Trogus has found me a lad for my apprentice. I like this house and I like the Forum Romanum—they are old.”

“Tell me about the wheezes.”

“Ah!” said the priest-physician, dark eyes widening. “You mean a wheezing noise when a patient breathes?”

“Yes.”

“But on expiration, not on inspiration.”

Caesar wheezed experimentally. “Breathing out, definitely.”

“Yes, I know of it. When the air is still and reasonably dry and the season is neither blossoms nor harvest, the patient is quite well unless some painful emotion troubles him. But when the air is full of pollen or little bits of straw or dust, or is too humid, the patient is distressed when he breathes. If he is not removed from the irritation, he goes into a fully fledged attack of wheezing, coughs until he retches, goes blue in the face as he struggles for every breath. Sometimes he dies.”

“My Uncle Sextus had it, and did die, but apparently of a lung inflammation due to exposure to extreme cold. Our family physician called it dyspnoea, as I remember,” said Caesar.

“No, it is not dyspnoea. That is a constant struggle for breath, rather than episodic,” said Hapd’efan’e firmly.

“Can this episodic non-dyspnoea run in families?”

“Oh, yes. The Greek name for it is asthma.”

“How best to treat it, Hapd’efan’e?”

“Certainly not the way the Greeks do, Caesar! They advocate bloodletting, laxatives, hot fomentations, a potion of hydromel mixed with hyssop, and lozenges made from galbanum and turpentine resin. The last two may help a little, I admit. But in our medical lore, it is said that asthmatics are suffused with sensitive feelings, that they take things to heart when others do not. We treat an attack with inhalation of sulphur fumes, but work more on avoiding attacks. We advise the patient to stay away from dust, tiny particles of grass or straw, animal hair or fur, pollen, heavy sea vapors,” said Hapd’efan’e.

“Is it present for life?”

“In some cases, Caesar, yes, but not always. Children who suffer from it sometimes grow out of it. A harmonious home life and general tranquillity are helpful.”

“My thanks, Hapd’efan’e.”

One of his worries about young Gaius Octavius had just been elucidated, though finding a solution would be hugely difficult. The boy shouldn’t be let near horses or mules—yes, that had been true of Uncle Sextus as well! Military training was going to be almost impossible, yet it was absolutely obligatory for a man with aspirations to be consul. All very well for Brutus! His family was so powerful, so ancestor-rich, and his fortune so vast that no colleague or peer would ever be indelicate enough to refer to Brutus’s lack of martial spirit. Whereas Octavius lacked imposing ancestors on his father’s side, and bore his father’s name. The patrician Julian blood was distaff blood, not manifest in his name. Poor fellow! His road to the consulship would prove hard, perhaps insuperable. If he lived to get that far.

Caesar got up to pace, bitterly disappointed. There didn’t seem to be enough of a chance that Gaius Octavius would survive to warrant making the lad Caesar’s heir. Back to Marcus Antonius—what a hideous prospect!

Lucius Marcius Philippus had extended an invitation to dinner at his spacious house on the Palatine to “celebrate your return to Rome” said the gracefully written note.

Cursing the waste of time but aware that family obligations insisted they attend, Caesar and Calpurnia arrived at the ninth hour of daylight to find themselves the only guests. Equipped with a dining room able to hold six couches, Philippus usually filled all six, but not today. Some warning alarm sounded; Caesar doffed his toga, made sure his thin layer of hair covered his scalp—he grew it long forward from the crown—and let the servant offer him a bowl of water to wash his feet. Naturally he was put in the locus consularis, the place of honor on Philippus’s own couch, with young Gaius Octavius at its far end from Caesar; Philippus took the middle position. His elder son wasn’t present—was that the reason for his sense that something was wrong? Caesar wondered. Was he here to be informed that Philippus was divorcing his wife for adultery with his son? No, no, of course not! That wasn’t the kind of news passed on at a dinner party with the wife sitting there. Marcia wasn’t present either; just Atia and her daughter, Octavia, joined Calpurnia on the three chairs opposite the only occupied couch.

Calpurnia looked delicious in an artfully draped lapis blue gown that echoed the color of her eyes; she was wearing the new sleeves, cut open from the shoulder and pinched together at intervals down the outer arm with little jeweled buttons. Atia had chosen a lavender blue that suited her fair beauty, and the young girl was exquisitely garbed in pale pink. How like her brother she was! The same masses of waving golden hair, his oval face, high cheekbones and nose with the sliding upward tilt. Her eyes alone were different, a clear aquamarine.

When Caesar smiled at Octavia she smiled back to reveal perfect teeth and a dimple in her right cheek; their eyes met, and Caesar drew an involuntary breath of astonishment. Aunt Julia! Aunt Julia’s gentle, peaceful soul looked out at him, warmed him to the marrow. She is Aunt Julia all over again. I shall give her a bottle of Aunt Julia’s perfume and rejoice. This girl will inspire love in all who meet her, she is a pearl beyond price. From her face he turned to gaze at her brother, to see an unqualified affection. He adores her, this elder sister.

The meal was quite up to Philippus’s standards, and included his favorite party fare—a smooth, yellowish mass of cream churned with eggs and honey inside an outer barrel filled with a mixture of snow and salt. It was brought at the gallop from the Mons Fiscellus, Italy’s highest mountain. The two young people spooned up the icy, melting poultice ecstatically, as did Calpurnia and Philippus. Caesar refused it. So did Atia.

“Between the eggs and the cream, Uncle Gaius, I simply dare not,” she laughed, but nervously. “Here, have some strawberries.”

“For Philippus, out of season means nothing,” said Caesar, growing ever more intrigued at the apprehension in the air. He lay back against his bolster and eyed Philippus mockingly, one fair brow raised. “There has to be a reason for this occasion, Lucius. Enlighten me.”

“As my note said, a celebration of your return to Rome. Ah—however, there is an additional reason to celebrate, I admit,” said Philippus as smoothly as his iced cream.

Caesar braced himself. “Since my great-nephew has been a man for nearly eight months, it can’t concern him. Therefore it must concern my great-niece. Is she betrothed?”

“She is,” said Philippus.

“Where’s the prospective bridegroom?”

“On his Etrurian estates.”

“May I ask his name?”

“Gaius Claudius Marcellus Minor,” said Philippus airily.

“Minor.”

“Well, it couldn’t be Major! He’s still abroad, unpardoned.”

“I wasn’t aware that Minor had been pardoned.”

“Since he did nothing wrong and remained in Italy, why does he need a pardon?” Philippus asked, beginning to sound truculent.

“Because he was senior consul when I crossed the Rubicon, and made no attempt to persuade Pompeius Magnus and the boni to reach an accommodation with me.”

“Come, Caesar, you know he was ill! Lentulus Crus did all the work, though as junior consul he didn’t hold the fasces for January. Once sworn in, Marcellus Minor was obliged to take to his bed, and there he remained for many moons. Since none of the physicians could find a reason for his sickness, I’ve always been of the opinion that it was Minor’s way of avoiding the displeasure of his far more militant brother and first cousin.”

“A coward, you’re implying.”

“No, not a coward! Oh, sometimes you’re too much the lawyer, Caesar! Marcellus Minor is simply a prudent man with the foresight to see that you can’t be beaten. It’s no disgrace for any man to deal craftily with his more unperceptive relatives,” said Philippus, grimacing. “Relatives can be a terrible nuisance—look at me, handicapped with a mother like Palla and a half brother who tried to murder his own father! Not to mention my father, who tergiversated perpetually. They’re the reasons why I adopted Epicureanism and have remained resolutely neutral all my political life. And look at you, with Marcus Antonius!”

Philippus scowled and clenched his fists, then disciplined himself to relax. “After Pharsalus, Marcellus Minor made a good recovery, and he’s been attending the Senate ever since you left for Africa. Not even Antonius objected to his presence, and Lepidus welcomed him.”

Caesar kept his face expressionless, but his eyes didn’t thaw. “Does this match please you, Octavia?” he asked, looking at her, and remembering that Aunt Julia had gone to Gaius Marius in a spirit of self-sacrifice, though apparently she had loved him. Caesar preferred to remember the pain Marius caused her.

Octavia shivered. “Yes, it pleases me, Uncle Gaius.”

“Did you ask for this match?”

“It is not my place to ask,” she said, the pink fading from her cheeks and lips.

“Have you met him, this forty-five-year-old?”

“Yes, Uncle Gaius.”

“And you can look forward to married life with him?”

“Yes, Uncle Gaius.”

“Is there anyone you would prefer to marry?”

“No, Uncle Gaius,” she whispered.

“Are you telling me the truth?”

The big, terrified eyes lifted to his; her skin was ashen now. “Yes, Uncle Gaius.”

“Then,” said Caesar, putting down his strawberries, “I offer you my felicitations, Octavia. However, as Pontifex Maximus, I forbid marriage confarreatio. An ordinary marriage, and you will retain the full control of your dowry.”

As pale as her daughter, Atia rose to her feet with rare clumsiness. “Calpurnia, come and see Octavia’s wedding chest.”

The three women left very quickly, heads down.

Voice conversational, Caesar addressed Philippus. “This is a very strange alliance, my friend. You have betrothed Caesar’s great-niece to one of Caesar’s enemies. What gives you the right to do that?”

“I have every right,” Philippus said, dark eyes burning. “I am the paterfamilias. You are not. When Marcellus Minor came to me with his offer, I considered it by far the best I’ve had.”

“Your status as paterfamilias is debatable. Legally I would have said she’s in her brother’s hand, now he’s of age. Did you consult her brother?”

“Yes,” said Philippus between his teeth, “I did.”

“And what was your answer, Octavius?”

The official man slid off the couch and transferred himself to the chair opposite Caesar, a place from which he could look at his great-uncle directly. “I considered the offer carefully, Uncle Gaius, and advised my stepfather to accept it.”

“Give me your reasons, Octavius.”

The lad’s breathing had become audible, a moist rattle on every expiration, but he was clearly not about to back down, even though the emotional strain, according to Hapd’efan’e, was of an order to produce wheezing.

“First of all, Marcellus Minor had come into possession of the estates of his brother, Marcus, and his first cousin, Gaius Major. He bought them at auction. When you listed the estates confiscate, Uncle, you did not list Minor’s, so my stepfather and I assumed Minor was an eligible suitor. Thus his wealth was my first reason. Secondly, the Claudii Marcelli are a great family of plebeian nobles with consuls going back many generations, and strong ties to the patrician Cornelii of the Lentulus branch. Octavia’s children by Marcellus Minor will have great social and political clout. Thirdly, I do not consider that the conduct of either this man or his brother, Marcus the consul, has been dishonest or unethical, though I admit that Marcus was a terrible enemy to you. But he and Minor adhered to the Republican cause because they deemed it right, and you of all men, Uncle Gaius, have never castigated men for that. Had the suitor been Gaius Marcellus Major, my decision would have been different, for he lied to the Senate and lied to Pompeius Magnus. Offenses you and I—and all decent men—find abhorrent. Fourthly, I watched Octavia very closely when they met, and talked to her afterward. Though you may not like him, Uncle, Octavia liked him very well. He is not ill looking, he is well-read, cultured, good-natured and besottedly in love with my sister. Fifthly, his future position in Rome depends heavily upon your favor. Marriage to Octavia strengthens that position. Which leads me to my sixth point, that he will be an excellent husband. I doubt Octavia will ever be able to reproach him for infidelity or treatment I for one would find repellent.”

Octavius squared his narrow shoulders. “Such are my reasons for thinking him a suitable husband for my sister.”

Caesar burst out laughing. “Good for you, young man! Not even Caesar could have been more dispassionate. I see that when I call the Senate to a meeting, I’ll have to make much of Gaius Claudius Marcellus Minor, crafty enough to pretend illness, shrewd enough to buy his brother’s and his first cousin’s property, and enterprising enough to cement his position with Caesar Dictator by a politic marriage.” He straightened on the couch. “Tell me, Octavius, if the situation were to change and an even more desirable marriage offer for your sister were to surface, would you break off the engagement?”

“Of course, Caesar. I love my sister very much, but we take pains to make our women understand that they must always help us enhance our careers and our families by marrying where they are instructed to marry. Octavia has wanted for nothing, from the most expensive clothes to an education worthy of Cicero. She is aware that the price of her comfort and privilege is obedience.”

The wheezing was dying away; Octavius had come through his ordeal relatively unscathed.

“What’s the gossip?” Caesar asked Philippus, who had sagged in relief.

“I hear that Cicero is at his villa in Tusculum writing a new masterpiece,” Philippus said uneasily. This had not been a restful dinner, and he could already feel a need for laserpicium.

“I detect a note of ominousness. The subject?”

“A eulogy on Cato.”

“Oh, I see. From that, I deduce that he still refuses to take his place in the Senate?”

“Yes, though Atticus is trying to make him see sense.”

“No one can!” said Caesar savagely. “What else?”

“Poor little Varro is beside himself. While Master of the Horse Antonius used his authority to strip Varro of some of his nicer estates, which he put in his own name. The income is handy now that he isn’t Master of the Horse. The moneylenders are dunning him for repayment of the loan he took out to buy that monument to bad taste, Pompeius’s palace on the Carinae.”

“Thank you for that snippet of information. I will attend to it,” Caesar said grimly.

“And one other thing, Caesar, which I think you should know about, though I’m afraid it will come as a blow.”

“Deal the blow, Philippus.”

“Your secretary, Gaius Faberius.”

“I knew something was wrong. What’s he done?”

“He’s been selling the Roman citizenship to foreigners.”

Oh, Faberius, Faberius! After all these years! It seems no one save Caesar himself can wait one or two months more for his share of the booty. My triumphs are imminent, and Faberius’s share would have earned him knight’s status. Now he gets nothing.

“Is his graft on a grand scale?”

“Grand enough to buy a mansion on the Aventine.”

“He mentioned a house.”

“I wouldn’t exactly call Afranius’s old place a mere house.”

“Nor would I.” Caesar swung himself backward on the couch and waited for the servant to slip on his shoes, buckle them. “Octavius, walk me home,” he commanded. “Calpurnia can stay to talk to the women a little longer—I’ll send a litter for her. Thank you, Philippus, for the welcome home party—and for the gossip. Most illuminating.”

The awkward guest gone, Philippus donned backless slippers and shuffled to his wife’s sitting room, where he found Calpurnia and Octavia examining piles of new clothing while Atia watched.

“Did he settle down?” Atia whispered, coming to the door.

“Once Octavius spoke his piece, his mood became sanguine. Your son is a remarkable fellow, my dear.”

“Oh, the relief! Octavia really does want this marriage.”

“I think Caesar will make Octavius his heir.”

Her face went to stark terror. “Ecastor, no!”

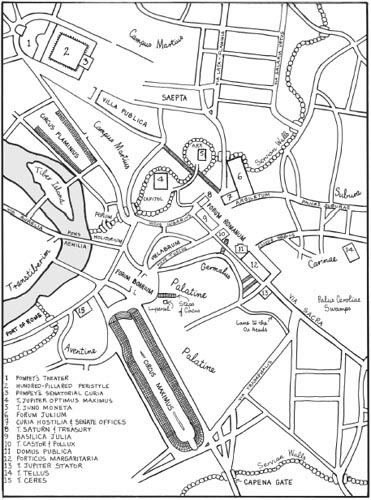

As Philippus’s commodious house lay on the Circus Maximus side of the Palatine and looked more west than north, Caesar and his companion, both togate, walked down to the upper Forum, then turned at the shopping center corner to descend the slope of the Clivus Sacer to the Domus Publica. Caesar stopped.

“Tell Trogus to send a litter for Calpurnia, would you?” he asked Octavius. “I want to inspect my new additions.”

Octavius was back in a moment; they resumed their walk down into the gathering shadows. The sun was low, bronzing the arched stories of the Tabularium and subtly changing the colors of the temples encrusting the Capitol above it. Though Jupiter Optimus Maximus dominated the higher hump and Juno Moneta the Arx, which was the lower hump, almost every inch of space was occupied by a temple to some god or aspect of a god, the oldest among them small and drab, the newest glowing with rich colors and glittering with gilding. Only the slight depression between the two humps, the Asylum, contained any free ground, planted with pencil pines and poplars, several ferny trees from Africa.

The Basilica Julia was completely finished; Caesar stood to regard its size and beauty with great satisfaction. Of two high stories, his new courthouse had a façade of colored marbles, Corinthian columns separated by arches in which stood statues of his ancestors from Aeneas through Romulus to that Quintus Marcius Rex who had built the aqueduct, and Gaius Marius, and Sulla, and Catulus Caesar. His mother was there, his first wife, Cinnilla, both Aunts Julia, and Julia, his daughter. That was the best part about being ruler of the world; he could erect statues of whomever he liked, including women.

“It’s so wonderful that I come to look at it often,” said Octavius. “No more postponing the courts because of rain or snow.”

Caesar passed to the new Curia Hostilia, home of the Senate. The Well of the Comitia had gone to make room for it; he had built a new, much taller and larger rostra that faced up the full length of the Forum, adorned with statues and the columns that held the captured ships’ beaks from which the rostra had gotten its name. There had been mutters that he was disturbing the mos maiorum with so much change, but he ignored them. Time that Rome looked better than places like Alexandria and Athens. Cato’s new Basilica Porcia remained at the foot of the Hill of the Bankers because, though it was small, it was very recent and sufficiently attractive to warrant preserving.

Beyond the Basilica Porcia and the Curia Hostilia was the Forum Julium, a huge undertaking that had meant resuming the business premises facing on to the Hill of the Bankers and excavating the slope to flatness. Not only that, but the Servian Walls had intruded upon its back, so he had paid to relocate these massive fortifications in a jog that went around his new forum. It was a rectangular open space paved in marble and surrounded on all four sides with a colonnade of splendid Corinthian pillars of purple marble, their acanthus leaf capitals gilded. A magnificent fountain decorated with statues of nymphs played in the middle of the space, while its only building, a temple to Venus Genetrix, stood at the back atop a high podium of steps. The same purple marble, the same Corinthian pillars, and atop the peak of the temple’s pediment, a golden biga—a statue of Victory driving two winged horses. The sun was almost gone; only the biga now reflected its rays.

Caesar produced a key and let them into the cella, just one big room with a glorious honeycombed ceiling ornamented by roses. The paintings hung on its walls made Octavius catch his breath.

“The ‘Medea’ is by Timomachus of Byzantium,” Caesar said. “I paid eighty talents for it, but it’s worth much more.”

It certainly is! thought the awed Octavius. Startlingly lifelike, the work showed Medea dropping the bloody chunks of the brothers she had murdered into the sea to slow her father down and enable her and Jason to escape.

“The Aphrodite arising from the sea foam and the Alexander the Great are by the peerless Apelles—a genius.” Caesar grinned. “However, I think I’ll keep the price I paid to myself. Eighty talents wouldn’t cover one of Apelles’s seashells.”

“But they’re here in Rome,” Octavius said fervently. “That alone makes a matchless painting worth the price. If Rome has them, then Athens or Pergamum don’t.”

The statue of Venus Genetrix—Venus the Ancestress—stood in the center of the back wall of the cella, painted so well that the goddess seemed about to step down off her golden pedestal. Like the statue of Venus Victrix atop Pompey’s theater, she bore Julia’s face.

“Arcesilaus did it,” Caesar said abruptly, turning away.

“I hardly remember her.”

“A pity. Julia was”—his voice shook—“a pearl beyond price. Any price at all.”

“Who did the statues of you?” Octavius asked.

A Caesar in armor stood to one side of Venus, a togate Caesar on the other.

“Some fellow Balbus found. My bankers have commissioned an equestrian statue of me to go in the forum itself, on one side of the fountain. I commissioned a statue of Toes to go on the other side. He’s as famous as Alexander’s Bucephalus.”

“What goes there?” Octavius asked, pointing to an empty plinth of some black wood inlaid with stones and enamel in most peculiar designs.

“A statue of Cleopatra with her son by me. She wanted to donate it, and as she says it will be solid gold, I didn’t like to put it outside, where someone enterprising might start shaving bits off it,” Caesar said with a laugh.

“When will she arrive in Rome?”

“I don’t know. As with all voyages, even the last, it depends on the gods.”

“One day,” said Octavius, “I too will build a forum.”

“The Forum Octavium. A splendid ambition.”

Octavius left Caesar at his door and commenced the uphill battle to Philippus’s house, never more conscious of his chronic shortness of breath than when toiling uphill. Dusk was drawing in, a chill descending; day’s trappings going, night’s coming, thought Octavius as the whirr of small bird wings was replaced by the ponderous flap of owls. A vast, billowing cloud reared above the Viminal, shot with a last gasp of pink.

I notice a change in him. He seems tired, though not with a physical weariness. More as if he understands that he will not be thanked for his efforts. That the petty creatures who creep about his feet will resent his brilliance, his ability to do what they have no hope of doing. “As with all voyages, even the last”—why did he phrase it so?

Just beyond the ancient, lichen-whiskered columns of the Porta Mugonia the hill sloped more acutely; Octavius paused to rest with his back pressed to the stone of one, thinking that the other looked like a brooding lemur escaped from the underworld, between its tubby body and its mushroom-cap hat. He straightened, struggled on a little farther, stopped opposite the lane that led to the Ox Heads, certainly the worst address on the Palatine. I was born in a house on that lane; my father’s father, a notorious miser, was still alive and my father hadn’t come into his inheritance. Then before we could move, he was dead, and Mama chose Philippus. A lightweight to whom the pleasures of the flesh are paramount.

Caesar despises the pleasures of the flesh. Not as a philosophy, like Cato, simply as unimportant. To him, the world is stuffed with things that need setting to rights, things that only he can see how to fix. Because he questions endlessly, he picks and chews, gnaws and dissects, pulls whatever it is into its component parts, then puts them together again in a better, more practical way.

How is it that he, the most august nobleman of them all, is not impaired by his birth, can see beyond it into illimitable distances? Caesar is classless. He is the only man I know or have read about who comprehends both the entire gigantic picture and every smallest detail in it. I want desperately to be another Caesar, but I do not have his mind. I am not a universal genius. I can’t write plays and poems, give brilliant extemporaneous speeches, engineer a bridge or a siege platform, draft great laws effortlessly, play musical instruments, general flawless battles, write crisp commentaries, take up shield and sword to fight in the front line, travel like the wind, dictate to four secretaries at once, and all those other legendary things he does out of the vastness of his mind.

My health is precarious and may grow worse, I stare that in the face every day. But I can plan, I have an instinct for the right alternative, I can think quickly, and I am learning to make the most of what few talents I have. If we share anything in common, Caesar and I, it is an absolute refusal to give up or give in. And perhaps, in the long run, that is the key.

Somehow, some way, I am going to be as great as Caesar.

He started the plod up the Clivus Palatinus, a slight figure that gradually merged into the gloom until it became a part of it. The Palatine cats, hunting for mouse or mate, slunk from shadow to shadow, and an old dog, half of one ear missing, lifted its leg to piss on the Porta Mugonia, too deaf to hear the bats.

Gaius Faberius, who had been with Caesar for twenty years, was dismissed in disgrace; Caesar convened a meeting of the Popular Assembly to witness the destruction of the tablets upon which the names of Faberius’s false citizens were inscribed.

“Due note has been taken of these names, and none will ever receive our citizenship!” he told the crowd. “Gaius Faberius has refunded the moneys paid to him by the false citizens, and said moneys will be donated to the temple of Quirinus, the god of all true Roman citizens. Furthermore, Gaius Faberius’s share of my booty will be put back into the general pool for division.”

Caesar took a stroll across his new, taller rostra, went down its steps and escorted the tiny figure of Marcus Terentius Varro on to its top. “Marcus Antonius, come here!” he called. Knowing what was coming, the scowling Antony ascended, stood to face Varro as Caesar informed the listening assembly that Varro had been a good friend to Pompey the Great, but never involved in the Republican conspiracy. The Sabine nobleman, a great scholar, received the deeds of his properties back, plus a fine of one million sesterces Caesar levied against Antony for causing Varro such distress. Then Antony had publicly to apologize.

“It’s not important,” Fulvia crooned when Antony stalked into her house immediately after the meeting. “Marry me, and you’ll have the use of my fortune, darling Antonius. You’re divorced now, there’s no impediment. Marry me!”

“I hate to be obligated to a woman!” Antony snapped.

“Gerrae!” she gurgled. “Look at your two wives.”

“They were forced on me, you’re not. But Caesar’s finally set the dates for his triumphs, so I’ll be getting my share of the Gallic booty in less than a month. Therefore I’ll marry you.”

His face twisted into hate. “Gaul first, then Egypt for King Ptolemy and Princess Arsinoë, then Asia Minor for King Pharnaces, and finally Africa for King Juba. Just as if Caesar’s never heard of the word Republicans! What a farce! I could kill him! I mean, he appoints me his Master of the Horse, which cuts me out of any of the booty for Egypt, Asia Minor or Africa—I had to sit in Italy instead of serving with him! And have I had any thanks? No! He just shits on me!”

An agitated nursemaid hurried in. “Domina, domina, little Curio has fallen over and hit his head!”

Fulvia gasped, threw her hands in the air and was off at a run. “Oh, that child! He’ll be the death of me!” she wailed.

Three men had witnessed this rather unromantic interlude: Poplicola, Cotyla and Lucius Tillius Cimber.

Cimber had entered the Senate as a quaestor the year before Caesar crossed the Rubicon, and supported his cause in the House. Unlike Antony, he could look forward to a share of the Asian and African booty, but they were nothing compared to what Antony would collect for Gaul. His vices were expensive, his association with Poplicola and Cotyla of some years’ duration, and his acquaintance with Antony had burgeoned since Antony’s return to Italy after Pharsalus. What he hadn’t realized until this illuminating scene was the depth of Antony’s hatred for his cousin Caesar; he truly did look as if he could do murder.

“Didn’t you say, Antonius, that you’re bound to be Caesar’s heir?” Poplicola asked casually.

“I’ve been saying it for years, what’s that to the point?”

“I think Poplicola is trying to find a way to introduce the matter into our conversation,” Cotyla said smoothly. “You’re Caesar’s heir, correct?”

“I have to be,” Antony said simply. “Who else is there?”

“Then if it irks you to depend on Fulvia for money because you love her, you do have another source, not so? Compared to Caesar, Fulvia’s a pauper,” Cotyla said.

Arrested, eyes gleaming redly, Antony looked at him. “Are you implying what I infer, Cotyla?”

Cimber moved quietly out of Antony’s line of sight, drawing no attention to his presence.

“We’re both implying it,” Poplicola said. “All you have to do to get out of debt permanently is kill Caesar.”

“Quirites, that’s a brilliant idea!” Antony’s fists came up, clenched in exultation. “It would be so easy too.”

“Which one of us should do it?” Cimber asked, inserting himself back into the action.

“I’ll do it myself. I know his habits,” Antony said. “He works until the eighth hour of night, then goes to bed for four hours and sleeps like the dead. I can go in over the top of his private peristyle wall, kill him and be out again before anybody knows I’m there. The tenth hour of night. And later, if there are any enquiries, the four of us will have been sitting drinking in old Murcius’s tavern on the Via Nova.”

“When will you do it?” asked Cimber.

“Oh, tonight,” Antony said cheerfully. “While I’m still in the mood.”

“He’s a close kinsman,” said Poplicola.

Antony burst into laughter. “What a thing for you to say, Lucius! You tried to murder your own father.”

All four men laughed uproariously; when Fulvia returned, she found Antony in an excellent humor.

Well after midnight Antony, Poplicola, Cotyla and Cimber staggered into old Murcius’s tavern very much the worse for wear, and usurped the table right at the back with the excuse that it was handy to the window in case anyone wanted to vomit. When the Forum watchman’s bell announced the tenth hour of night, Antony slipped out of the window while Cotyla, Cimber and Poplicola clustered around their table and continued their rowdy banter as if Antony were still a part of it.

They expected him to be away some small while, as the Via Nova was perched atop a thirty-foot cliff; Antony would have to run a short distance to the Ringmakers’ Steps, which would bring him to the back of the Porticus Margaritaria and the Domus Publica.

He returned quite quickly, looking furious. “I don’t believe it!” he gasped, out of breath. “When I got to the peristyle wall, there were servants sitting on top of it with torches!”

“Is this a new thing, for Caesar to mount a watch?” Cimber asked curiously.

“I don’t know, do I?” snarled Antony. “This is the first time I’ve ever tried to sneak into the place during the night.”

Two days later Caesar summoned the Senate to the very first meeting of that body since his return; the venue was Pompey’s Curia on the Campus Martius behind his hundred-pillared courtyard and the vast bulk of his theater. Though it meant a fairly long walk, those summoned breathed a sigh of relief. Pompey’s Curia had been specifically built for meetings of the Senate, and could accommodate everyone in comfort and proper gradation. As it lay outside the pomerium, in the days when the Curia Hostilia of the Forum had existed, it was mostly used for discussing foreign war, a subject considered inappropriate for pomerium-confined meetings.

Caesar was already ensconced on the podium in his curule chair, a folding table in front of him loaded with documents he had to find time to read, wax tablets and a steel stylus used to gouge writing in the wax. He took no notice as men dribbled in, had their slaves set up their stools on the correct tier: the top one for pedarii, senators allowed to vote but not speak; the middle one for holders of junior magistracies, namely ex-aediles and ex-tribunes of the plebs; and the front, lowest tier for ex-praetors and consulars.

Only when Fabius, his chief lictor, tapped him on the shoulder did Caesar lift his head and gaze about. Not too bad on the back benches, he thought. So far he had appointed two hundred new men, including the three centurions who had won the corona civica. Most were scions of the families who made up the Eighteen senior Centuries, but some were from prominent Italian families, and a few, like Gaius Helvius Cinna, from Italian Gaul. The “unsuitable” appointments had not met with approval from those of Rome’s old noble families who regarded the Senate as a body purely for them. The word had gone around that Caesar was filling the Senate with trousered Gauls and ranker legionaries, along with rumors that he intended to make himself King of Rome. Every day since he had come back from Africa someone asked Caesar when he was going to “restore the Republic”—a question he ignored. Cicero was being very vocal about the deteriorating exclusivity of the Senate, an attitude heightened by the fact that he himself was not a Roman of the Romans, but a New Man from the country. The more of his like filled the Senate, the less his own triumph in attaining it against all the odds. He was, besides, a colossal snob.

A few men Caesar had yearned to see there were sitting on the front benches: the two Manius Aemilius Lepiduses, father and son; Lucius Volcatius Tullus the elder; Calvinus; Lucius Piso; Philippus; two members of the Appius Claudius Pulcher gens. And some men not so yearned for: Marcus Antonius and Octavia’s betrothed, Gaius Claudius Marcellus Minor. But no Cicero. Caesar’s lips thinned. No doubt too busy eulogizing Cato to attend.

The podium was quite crowded. Himself and Lepidus, the two consuls, and six of the praetors, including his staunch ally Aulus Hirtius and Volcatius Tullus’s son. That boor Gaius Antonius had his behind on the tribunician bench, along with the other, equally uninspiring, holders of the tribunate of the plebs.

Enough, thought Caesar, counting more than a quorum. He rose to pull a fold of toga over his head and say the prayers, waited for Lucius Caesar to take the auspices, then got down to business.

“Some sad news first, conscript fathers,” he said in his usual deep voice; the acoustics in Pompey’s Curia were good. “I have had word that the last of the Licinii Crassi, Marcus the younger son of the great consular, has died. He will be missed.”

He swept on without looking as if his next item of news was going to cause a sensation, and so caught the senators unaware. “I have to draw a second unpleasantness to your attention. Namely, that Marcus Antonius has made an attempt on my life. He was seen trying to enter the Domus Publica at an hour when I am known to be asleep, and the interior deserted. His garb was not formal—a tunic and a knife. Nor was his mode of entry formal—the wall of my private peristyle.”

Antony sat, rigid with shock—how did Caesar know? No one had seen him, no one!

“I mention this with no intention of pursuing the matter. I simply draw your attention to it, and take leave to inform all of you that I am not as unprotected as I may seem. Therefore those of you who do not approve of my dictatorship—or of my methods!—had best think twice before deciding that you will rid Rome of this tyrant Caesar. I tell you frankly that my life has been long enough, whether in years or renown. However, I am not yet so tired of it that I will do nothing to avert its being terminated by a deed of murder. Remove me, and I can assure you that Rome will suffer far greater ills than Caesar Dictator. Rome’s present situation is much the same as it was when Lucius Cornelius Sulla took up the dictatorship—she needs one strong hand, and in me she has that hand. Once I have set my laws in place and made sure that Rome will survive to grow ever greater, I will lay down my dictatorship. However, I will not do that until my work is entirely finished, and that may take many years. So be warned, and cease these pleas that I ‘return the Republic’ to its former glory.

“What glory?” he thundered, making his appalled audience jump. “I repeat, what glory? There was no glory! Just a fractious, obstinate, conceited little group of men jealously defending their privileges. The privilege of going to govern a province and rape it. The privilege of granting business colleagues the opportunity to go to a province and rape it. The privilege of having one law for some, and another law for others. The privilege of putting incompetents in office simply because they bear a great name. The privilege of voting to quash laws that are desperately needed. The privilege of preserving the mos maiorum in a form suitable for a small city-state, but not for a worldwide empire.”

They were sitting bolt upright, their faces slack. For some, it had been a long time since this Caesar had last bellowed his radical ideas to the House; for others, this was the first time.

“If you believe that all Rome’s wealth and privilege should remain in the Eighteen from which you come, senators, then I will cut you down to size. I intend to restructure our society to distribute wealth more equally. I will make laws encouraging the growth of the Third and Fourth Classes, and enhance the lot of the Head Count by encouraging them to emigrate to places where they can rise into higher classes. Further to this, I am introducing a means test on the distribution of free grain so that men who can afford to buy grain will no longer be able to obtain it free. At present there are three hundred thousand recipients of the free grain dole. I will cut that figure in half overnight. I will also make it impossible for a man to free slaves in order to benefit from the grain dole. How am I going to do this? By holding a new kind of census in November. My census agents will go from door to door throughout Rome, Italy, and all the provinces. They will assemble mountains of facts about housing, rents, hygiene, income, population, literacy and numeracy, crime, fire, and the number of children, aged and slaves in every family. My agents will also ask members of the Head Count if they would like to emigrate abroad to the colonies I will found. Since Rome now has a huge surplus of troop transport ships, I will use them.”

Piso spoke. “Be he rich or poor, Caesar, every Roman citizen is entitled to the free grain dole. I warn you that I will oppose any attempt to impose a means test!” he said loudly.

“Oppose all you like, Lucius Piso, the law will come into effect anyway. I will not be gainsaid! Nor do I advise you to oppose—it will harm your career. The measure is fair and just. Why should Rome pay out her precious moneys to men like you, well able to buy grain?” asked Caesar, voice hard.

There were mutterings, dark looks; the old, high-handed, arrogant Caesar was back with a vengeance. However, the faces on the back benches, though alarmed, were not angry. They owed their position to Caesar, and they would vote for his laws.

“There will be innumerable agrarian laws,” Caesar continued, “but there’s no need for fury, so don’t get furious. Any land I buy in Italy and Italian Gaul for retiring legionaries will be paid for up-front and at full value, but most of the agrarian legislation will involve foreign land in the Spains, the Gauls, Greece, Epirus, Illyricum, Macedonia, Bithynia, Pontus, Africa Nova, the domain of Publius Sittius, and the Mauretanias. At the same time as some of our Head Count and some of our legionaries go to settle in these colonies, I will also grant the full citizenship to deserving provincials, physicians, schoolteachers, artisans and tradesmen. If resident in Rome, they will be enrolled in the four urban tribes, but if resident in Italy, in the rural tribe common to the district wherein they live.”

“Do you intend to do anything about the courts, Caesar?” asked the praetor Volcatius Tullus in an attempt to calm the House.

“Oh, yes. The tribunus aerarius will disappear from the jury list,” the Dictator announced, willing to be sidetracked. “The Senate will be increased to one thousand members, which will, with the knights of the Eighteen, provide more than enough jurors for the courts. The number of praetors will go to fourteen per year to enable swifter hearings in the busier courts. By the time that my legislation is done, there will hardly be any need for the Extortion Court, because governors and businessmen in the provinces will be too hamstrung to extort. Elections will be better regulated, so the Bribery Court will also stultify. Whereas ordinary crimes like murder, theft, violence, embezzlement and bankruptcy need more courts and more time. I also intend to increase the penalty for murder, but not in a way that disturbs the mos maiorum. Execution for crime and imprisonment for crime, two concepts alien to Roman thought and culture, will not be introduced. Rather, I will increase the time of exile and make it absolutely impossible for a man sentenced to exile to take his money with him.”

“Aiming for Plato’s ideal republic, Caesar?” Piso sneered; he was taking the greatest offense.

“Not at all,” Caesar said genially. “I’m aiming for a just and practical Roman republic. Take violence, for example. Those desirous of organizing street gangs will find it much harder, for I am going to abolish all clubs and sodalities save those that are harmless of intent—Jewish synagogues, trade and professional guilds—and the burial clubs, of course. Crossroads colleges and other places where troublemakers can meet on a regular basis will disappear. When men have to buy their own wine, they drink less.”

“I hear,” said Philippus, who was a huge landowner, “a tiny rumor that you have plans to break up latifundia.”

“Thank you for reminding me, Lucius Philippus,” said Caesar, smiling broadly. “No, latifundia will not be broken up unless the state has bought them for soldier land. However, in future no owner of a latifundium will be allowed to run it entirely on slaves. One-third of his employees must be free men of the region. This will help the jobless rural poor as well as local merchants.”

“That’s ridiculous!” yelled Philippus, dark face flushed. “You’re going to introduce legislation to tamper with everything! A man will soon have to apply for permission to fart! You, Caesar, are deliberately setting out to strip Rome of any kind of First Class! Where do you get these insane ideas from? Help the rural poor indeed! Aman has rights, and one of them is the right to run his businesses and enterprises exactly how he wants! Why should I have to pay wages to one-third of my latifundia workers when I can buy cheap slaves and not pay them at all?”

“Every man should pay his slaves a wage, Philippus. Can’t you see,” Caesar asked, “that you have to buy your slaves? Then you have to build ergastula to house them, buy food to feed them, and use up twice as many workers to supervise these unwilling men? If you were any good at arithmetic or you had agents who could add up two and two, you’d soon realize that employing the free is cheaper. You don’t have the initial outlay, and you don’t need to house or feed free men. They go home each night and eat out of their own gardens because they have wives and children to grow for them.”

“Gerrae!” Philippus growled, subsiding.

“What, no sumptuary laws?” Piso asked.

“Sheaves of them,” Caesar answered readily. “Luxuries will be severely taxed, and while I will not forbid the erection of expensive tombs, the man who builds one will have to pay Rome’s Treasury the same amount of money he pays his tomb builder.”

He looked down at Lepidus, who hadn’t said a word, and raised a brow. “Junior consul, just one more thing and you can dismiss the meeting. There will be no debate.”

He turned back to the House and proceeded to tell it that he intended to bring the calendar into line with the seasons for perpetuity, so this year would be 455 days long: Mercedonius was over, but a 67-day period called Intercalaris would also be added following the last day of December. New Year’s Day, when eventually it came, would be exactly where it was supposed to be, one-third of the way through winter.

“There isn’t a name for you, Caesar,” Piso declared as he left, his whole body trembling. “You’re a—a—a freak!”

Miming injured innocence to those who stared at him, Antony waited to get Caesar to himself. “What do you mean, Caesar, to come out with that assassination rot? Then you barged on about returning the Republic to its days of glory without even giving me a chance to defend myself!” He pushed his face aggressively close to Caesar’s. “First you humiliate me in public, now you’ve accused me of attempted murder in the Senate! It isn’t true—ask any of the three men I was with all that night at Murcius’s tavern!”

Caesar’s eyes wandered to Lucius Tillius Cimber, descending from the top left-hand tier with his stool slave following him. What an interesting man. Full of useful information.

“Do go away, Antonius,” he said wearily. “As I’ve already indicated, I have no intention of pursuing the matter. However, I felt that your playing the fool with murder was an excellent excuse to inform the House that I’m not so easily gotten rid of. In the financial soup worse than ever, eh?”

“I’m marrying Fulvia and shortly I’ll have my share of the Gallic booty,” Antony countered. “Why do I need to murder you?”

“One question, Antonius—how do you know which night the attempt was made if you didn’t make it? I neglected to mention the date. Of course you tried! In a temper, following the Varro apology. Now go away.”

“I despair for Antonius,” said Lucius Caesar, approaching.

Almost to the doorway, his lictors passed outside, Caesar turned to look back down the ostentatious hall with its splendid marbles and not-quite-right color scheme—typical of its author! And there at the rear of the platform accommodating the curule magistrates stood the statue of Pompey the Great in his white marble toga with the purple marble border, his face, hands, right arm and calves painted to the perfect tones of his skin, even including the faint freckles. The bright gold hair was superbly done, the vivid blue eyes seeming to sparkle with life.

“A very good likeness,” Lucius said, following his cousin’s gaze.

“I hope you don’t mean to emulate Magnus and put a statue of yourself behind the curule magistrates in your new Curia?”

“It’s not a bad idea, Lucius, when you think about it. If I were away for ten years, every time the Senate met in its Curia it would be reminded of the fact that I’ll be back.”

They moved outside, passed through the colonnade and emerged on the road back to town.

“One thing I meant to ask you, Lucius. How did young Gaius Octavius go when he served as city prefect?”

“Didn’t you ask him in person, Gaius?”

“He didn’t mention it, and I confess it slipped my mind.”

“You need have no fears, he did very well. Praefectus urbi notwithstanding, he occupied the urban praetor’s booth with a lovely mixture of humility and quiet confidence. He handled the inevitable one or two contentious situations like a veteran—very cool, asked all the right questions, delivered the proper verdict. Yes, he did very well.”

“Did you know that he suffers the wheezing sickness?”

Lucius stopped. “Edepol! No, I didn’t.”

“It represents a dilemma, doesn’t it?”

“Oh, yes.”

“Yet I think it has to be him, Lucius.”

“There’s time enough.” Lucius put an arm around Caesar’s shoulders, squeezed them comfortingly. “Don’t forget Caesar’s luck, Gaius. Whatever you decide carries Caesar’s luck with it.”