2

Cleopatra arrived in Rome at the end of the first nundinum in September. She was conveyed from Ostia in a curtained litter, an enormous procession of attendants before her and behind her, including a detachment of the Royal Guard in their quaint hoplite gear, but mounted on snow-white horses with purple tack. Her son, a little unwell, traveled in another litter with his nursemaids, and a third one held King Ptolemy XIV, her thirteen-year-old husband. All three litters had cloth-of-gold curtains, the jewels in the gilded woodwork flashing in the bright sun of a beautiful early summer’s day, ostrich-feather plumes caked in gold dust nodding at all four corners of the faience-tiled roofs. Each was borne by eight powerfully built men with plummy black skin, clad in cloth-of-gold kilts and wide gold collars, big feet bare. Apollodorus rode in a canopied sedan chair at the head of the column, a tall gold staff in his right hand, his nemes headdress cloth-of-gold, his fingers covered with rings, the chain of his office around his neck. The several hundred attendants wore costly robes, even the humblest among them; the Queen of Egypt was determined to make an impression.

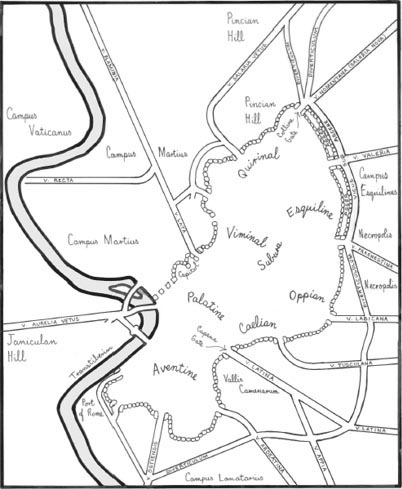

They had started out at dawn with a good percentage of Ostia escorting them, and as Ostia drew farther away, others took their place; anyone who had occasion to be on the Via Ostiensis that morning thought it more fun to join the royal parade than go about normal business. Cornelius the lictor, deputed to act as guide, picked them up a mile from the Servian Walls and viewed his charge with an awe bordering on profound—oh, what a tale he’d have to tell when he got back to the College of Lictors! It was noon by this time, and Apollodorus stared at the looming ramparts in relief. But then Cornelius led them around the outskirts of the Aventine to the wharves of the Port of Rome, there to halt. The Lord High Chamberlain began to frown; why were they not entering the city, why was her majesty in this decrepit, seedy neighborhood?

“We boat across the river here,” Cornelius explained.

“Boat? But the city is to our right!”

“Oh, we’re not entering the city,” Cornelius said in affable innocence. “The Queen’s palace is across the Tiber at the foot of the Janiculan Hill, which makes this the easiest place to cross—wharves on both sides.”

“Why isn’t the Queen’s palace inside the city?”

“Tch, tch, that would never do,” said Cornelius. “The city is forbidden to any anointed sovereign because to enter it means crossing the sacred pomerium and laying down all imperial power.”

“Pomerium?” asked Apollodorus.

“The invisible boundary of the city. Within it, no one has imperium except the dictator.”

By this time half the Port of Rome had gathered to gawk, as had grooms, stablehands, slaughtermen and shepherds from the Campus Lanatarius. Cornelius was wishing that he had brought other lictors to keep the crowds at bay—what a circus! And so Rome’s lowly regarded it, a wonderful, unexpected circus on an ordinary working day. Luckily for the Egyptians a succession of barges drew into the wharf; the litters and sedan chair were quickly conveyed on board the first of them, and the horde of attendants pushed on to the others with the Royal Guard bringing up the rear, dismounted and soothing their fractious horses.

Apollodorus’s frown gathered mightily when they were off-loaded into the mean alleys of Transtiberim, where he was forced to order the Royal Guards into tight formation around the litters to prevent the dirty, ragged inhabitants from gouging jewels out of the litter posts with their knives—even the women seemed to carry knives. Nor was he amused when, after yet another long plod, he found that the Queen’s palace had no walls to keep the Transtiberini out!

“They’ll give up and go home,” said the unconcerned Cornelius, leading the way through an arch into a courtyard. Apollodorus’s answer was to swing the Royal Guard across this entrance and tell it to stay there until the Transtiberini went home. What kind of place was this, that there were no walls to exclude the dross of humanity from the residences of their betters? And what kind of place was this, that her majesty’s only deputed escort was one lictor minus his fasces? Where was Caesar?

The Queen’s belongings had preceded her by sufficient time to ensure that when she emerged from her litter and walked into the vast atrium, her eyes could rest on a properly outfitted interior, from paintings and tapestries on the walls to rugs, chairs, tables, couches, statues, her huge collection of pedestals containing busts of all the Ptolemies and their wives—an air of inhabited comfort.

She was not in a good mood. Naturally she had peeked between the curtains at this alien landscape of rearing hills, seen the massive Servian Walls, the terra-cotta roofs dotting the hills inside them, the tall thin pines, the leafy trees, the pines shaped like parasols. A shock for her as well as Apollodorus when they bypassed the city and entered a dockland dominated by a tall mount of broken pots and festering rubbish. Where was the guard of honor Caesar should have sent? Why had she been ferried across that—that creek to a worse slum, then hustled to nowhere? For that matter, why hadn’t Caesar answered any of the barrage of notes she had sent him since arriving in Ostia, save for the first? And that terse communication simply told her to move into her palace as soon as she wished!

Cornelius bowed. He knew her from Alexandria, though he was inured enough to eastern rulers to understand that she would not recognize him. Nor did she; her majesty was in a huff. “I am to give you Caesar’s compliments, your majesty,” he said. “As soon as he finds the time, he’ll visit you.”

“As soon as he finds the time, he’ll visit me,” she echoed to Cornelius’s receding back. “He’ll visit! Well, when he does, he’ll wish he hadn’t!”

“Calm down and behave yourself, Cleopatra,” said Charmian firmly; brought up from infancy with their queen, she and Iras stood in no fear of her, divined her every mood.

“It’s very nice,” Iras contributed, gazing about. “I love the huge pool in the middle of the room, and how cunning to put dolphins and tritons in it.” She looked up at the sky with less approval. “You’d think they’d put a roof over it, wouldn’t you?”

Cleopatra sat on her temper. “Caesarion?” she asked.

“He’s been taken straight to the nursery, but don’t worry, he’s improving.”

For a moment the Queen stood uncertainly, chewing her lip; then she shrugged. “We are in a strange land of high mountains and peculiar trees, so I suppose we must expect the customs to be equally strange and peculiar. Since apparently Caesar isn’t going to come at a run to welcome me, there’s no point in keeping my regalia on. Where are the nursery and my private rooms?”

Changed into a plain Greek gown and reassured that Caesarion was indeed improving, she toured the palace with Charmian and Iras. On the small side, but adequate, was their verdict. Caesar had given her one of his own freedmen, Gaius Julius Gnipho, as her Roman steward, who would be in charge of things like purchasing food and household items.

“Why are there no gauze curtains to shield the windows, and none around the beds?” Cleopatra asked.

Gnipho looked bewildered. “I’m sorry, I don’t understand.”

“Are there no mosquitoes here? No night moths or bugs?”

“We have them aplenty, your majesty.”

“Then they must be kept outside. Charmian, did we bring any linen gauze with us?”

“Yes, more than enough.”

“Then see it’s put up. Around Caesarion’s cot at once.”

Religion had not been neglected; Cleopatra had carried a select pantheon with her, of painted wood rather than solid gold, dressed in their proper raiment—Amun-Ra, Ptah, Sekhmet, Horus, Nefertem, Osiris, Isis, Anubis, Bastet, Taweret, Sobek and Hathor. To care for them and her own needs she had brought a high priest, Pu’em-re, and six mete-en-sa to assist him.

The agent, Ammonius, had been to Ostia to see his queen on several occasions, and had made sure that the builders provided one room with plastered walls; this would be the temple, once the mete-en-sa had painted the walls with the prayers, the spells and the cartouches of Cleopatra, Caesarion and Philadelphus.

Her mood dropping inexorably toward depression, Cleopatra fell to abase herself before Amun-Ra. The formal prayer, in old Egyptian, she spoke aloud, but after it was finished she remained on her knees, hands and brow pressed to the cold marble floor, and prayed silently.

God of the Sun, bringer of light and of life, preserve us in this daunting place to which we have taken your worship. We are far from home and the waters of Nilus, and we have come only to keep faith with thee, with all our gods great and small, of the sky and the river. We have journeyed into the West, into the Realm of the Dead, to be quickened again, for Osiris Reincarnated cannot come to us in Egypt. Nilus inundates perfectly, but if we are to maintain the Inundation, it is time that we bear another child. Help us, we pray, endure our exile among these unbelievers, keep our Godhead intact, our sinews taut, our heart strong, our womb fruitful. Let our Son, Ptolemy Caesar Horus, know his divine Father, and grant us a sister for him so that he may marry and keep our blood pure. Nilus must inundate. Pharaoh must conceive again, many times.

When Cleopatra had set out from Alexandria with her fleet of ten warships and sixty transports, her excitement had infected everyone who traveled with her. For Egypt in her absence she had no fears; Publius Rufrius guarded it with four legions, and Uncle Mithridates of Pergamum occupied the Royal Enclosure.

But by the time they put into Paraetonium for water, her excitement had evaporated—who could have imagined the boredom of looking at nothing but sea? At Paraetonium the fleet’s speed increased, for Apeliotes the East Wind began to blow and pushed them west to Utica, very quiet and subdued after Caesar’s war. Then Auster, the South Wind, came along to blow them straight up the west coast of Italy. When the fleet made harbor in Ostia, it had been at sea from Alexandria for only twenty-five days.

There in Ostia the Queen had waited aboard her flagship until all her goods had been brought ashore and word came that her palace was ready for occupation. Bombarding Caesar with letters, standing at the rail every day hoping to see Caesar being borne out to see her. His terse note had said only that he was in the midst of drafting a lex agraria, whatever that might be, and could not spare the time to see her. Oh, why were his communications always so unemotional, so unloving? He spoke as if she were some ordinary suppliant ruler, a nuisance for whom he would find time when he could. But she wasn’t ordinary, or a suppliant! She was Pharaoh, his wife, the mother of his son, Daughter of Amun-Ra!

Caesarion had chosen to come down with a fever while they were moored in that ghastly, muddy harbor. Did Caesar care? No, Caesar didn’t care. Hadn’t even replied to that letter.

Now here she was, as close to Rome as she was going to get, if Cornelius the lictor was right, and still no Caesar.

At dusk she consented to eat what Charmian and Iras brought her—but not until it had been tasted. A member of the House of Ptolemy did not simply give a little of the food and drink to a slave; a member of the House of Ptolemy gave the food and drink to the child of a slave known to love his children dearly. An excellent precaution. After all, her sister Arsinoë was here in Rome, though, not being an anointed sovereign, no doubt she lived within its walls. Housed by a noblewoman named Caecilia, Ammonius had reported. Living on the fat of the land.

The air was different, and she didn’t like it. After dark it held a chill she had never experienced, though it was supposed to be early summer. This cold stone mausoleum contributed to the miasma that curled off the so-called river, which she could see from the high loggia. So damp. So foreign. And no Caesar.

Not until the middle hour of the night by the water clock did she go to bed, where she tossed and turned until finally she fell asleep after cock crow. A whole day on land, and no Caesar. Would he ever come?

What woke her was an instinct; no sound, no ray of light, no change in the atmosphere had the power Cha’em had inculcated in her as a child in Memphis. When you are not alone, you will wake, he had said, and breathed into her. Since then, the silent presence of another person in the room would wake her. As it did now, and in the way Cha’em had taught her. Open your eyes a tiny slit, and do not move. Watch until you identify the intruder, only then react in the appropriate way.

Caesar, sitting in a chair to one side of the bed at its foot, looking not at her but into that distance he could summon at will. The room was light but not bright, every part of him was manifest. Her heart knocked at her ribs, her love for him poured out in a huge spate of feeling, and with it a terrible grief. He is not the same. Immeasurably older, so very tired. His bones are such that his beauty will persist beyond death, but something is gone. His eyes have always been pale, but now they are washed out, making that black ring around the irises starker still. All her own resentments and irritations seemed suddenly too petty to bear; she curved her lips into a smile, pretended to wake and see him, lifted her arms in welcome. It is not I who needs succor.

His eyes came back from wherever they had been and saw her; he smiled that wonderful smile, twisted out of the enveloping toga as he rose in a way she could never fathom. Then his arms were around her, clutching her like a drowning man a spar. They kissed, first an exploration of the softness of lips, then deeply. No, Calpurnia, he is not like this with you. If he were, he would not need me, and he needs me desperately. I sense it all through me, and I answer it all through me.

“You’re rounder, little scrag,” he said, mouth in the side of her neck, smooth hands on her breasts.

“You’re thinner, old man,” she said, arching her back.

Her thoughts turned inward to her womb as she opened herself to him, held him strongly but tenderly. “I love you,” she said.

“And I you,” he said, meaning it.

There was divine magic in mating with an anointed sovereign, he had never felt that so intensely before, but Caesar was still Caesar; his mind never entirely let go, so though he made ardent love to her for a long time, he deprived her of his climax. No sister for Caesarion, never a sister for Caesarion. To give her a girl was a crime against all that Jupiter Optimus Maximus was, that Rome was, that he was.

She wasn’t aware of his omission, too satisfied herself, too swept out of conscious thought, too devastated at being with him again after almost seventeen months.

“You’re sopping with juice, time for a bath,” he said to reinforce her delusion; Caesar’s luck that she produces so much moisture herself. Better that she doesn’t know.

“You must eat, Caesar,” she said after the bath, “but first, a visit to the nursery?”

Caesarion was fully recovered, had woken his usual cheerful, noisy self. He flew with arms outstretched to his mother, who picked him up and showed him proudly to his father.

I suppose, thought Caesar, that once I looked much like this. Even I can see that he’s inarguably mine, though I recognize it mostly in the way he echoes my mother, my sisters. His regard is the same steady assessment Aurelia gave her world, his expression isn’t mine. A beautiful child, sturdy and well nourished, but not fleshy. Yes, that’s genuine Caesar. He won’t run to fat the way the Ptolemies do. All he has of his mother are the eyes, though not in color. Less sunk in their orbits than mine, and a darker blue than mine.

He smiled, said in Latin, “Say ave to your tata, Caesarion.”

The eyes widened in delight, the child turned his head from this stranger to his mother’s face. “That’s my tata?” he asked in quaintly accented Latin.

“Yes, your tata’s here at last.”

The next moment two little arms were reaching for him; Caesar took him, hugged him, kissed him, stroked the fine, thick gold hair, while Caesarion cuddled in as if he had always known this strange man. When she went to take him from Caesar, he refused to go back to his mother. In his world he has missed a man, thought Caesar, and he needs a man.

Dinner forgotten, he sat with his son on his lap and found out that Caesarion’s Greek was far better than his Latin, that he did not indulge in baby talk, and uttered his sentences properly parsed and analyzed. Fifteen months old, yet already an old man.

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” Caesar asked.

“A great general like you, tata.”

“Not Pharaoh?”

“Oh, pooh, Pharaoh! I have to be Pharaoh, and I’ll be that before I grow up,” said the child apparently not enamored of his regnant destiny. “What I want to be is a general.”

“Whom would you war against?”

“Rome’s and Egypt’s enemies.”

“All his toys are war toys,” Cleopatra said with a sigh. “He threw away his dolls at eleven months and demanded a sword.”

“He was talking then?”

“Oh yes, whole sentences.”

Then the nursemaids bore down and took him off to feed him; expecting tears and protests, Caesar saw in some amazement that his son accepted the inevitable quite happily.

“He doesn’t have my pride or temper,” he said as they walked through to the dining room, having promised Caesarion that tata would be back. “Sweeter natured.”

“He’s God on earth,” she said simply. “Now tell me,” she said, settling into Caesar’s side on the same couch, “what is making you so tired.”

“Just people,” he said vaguely. “Rome doesn’t appreciate the rule of a dictator, so I’m continually opposed.”

“But you always said you wanted opposition. Here, drink your fruit juice.”

“There are two kinds of opposition,” he said. “I wanted an atmosphere of intelligent debate in the Senate and comitia, not endless demands to ‘bring back the Republic’—as if the Republic were some vanished entity akin to Plato’s Utopia. Utopia!” He made a disgusted sound. “The word means ‘Nowhere’! When I ask what’s wrong with my laws, they complain that they’re too long and complicated to read, so they won’t read them. When I ask for good suggestions, they complain that I’ve left them nothing to suggest. When I ask for co-operation, they complain that I force them to co-operate whether they want to or not. They admit that many of my changes are highly beneficial, then turn around and complain that I change things, that change is wrong. So the opposition I get is as devoid of reason as Cato’s used to be.”

“Then come and talk to me,” she said quickly. “Bring me your laws and I’ll read them. Tell me your plans and I’ll offer you constructive criticism. Try out your ideas on me and I’ll give you a considered opinion. If another mind is what you need, my dearest love, mine is the mind of a dictator in a diadem. Let me help you, please.”

He reached out to take her hand, held it to his lips and kissed it, the shadow of a smile filling his eyes with some of the old vigor and sparkle. “I will, Cleopatra, I will.” The smile grew, his gaze became more sensuous. “You’ve budded into a very special beauty, my love. Not a Praxiteles Aphrodite, no, but motherhood and maturity have turned you into a deliciously desirable woman. I missed your lion’s eyes.”

* * *

Said Cicero to Marcus Junius Brutus in a letter written two nundinae later:

You will miss the Great Man’s triumphs, my dear Brutus, sitting up there amid the Insubres. Lucky you. The first one, for Gaul, is to be held tomorrow, but I refuse to attend. Therefore I see no reason to delay this missive, bursting as it is with news amorous and marital.

The Queen of Egypt has arrived. Caesar has set her up in high style in a palace beneath the Janiculan Hill far enough upstream to look across Father Tiber at the Capitol and the Palatine rather than at the stews of the Port of Rome. None of us was privileged to see her own private triumphal parade as she came up the Via Ostiensis, but gossip says it was awash in gold, from the litters to the costumes.

With her she brought Caesar’s presumed son, a toddling babe, and her thirteen-year-old husband, King Ptolemy the something-or-other, a surly, adipose lad with nothing to say for himself and a very healthy fear of his big sister/wife. Incest! The game the whole family can play. I said that about Publius Clodius and his sisters once, I remember.

There are slaves, eunuchs, nursemaids, tutors, advisers, clerks, scribes, accountants, physicians, herbalists, crones, priests, a high priest, minor nobles, a royal guard two hundred strong, a philosopher or four, including the great Philostratus and the even greater Sosigenes, musicians, dancers, mummers, magicians, cooks, dishwashers, laundresses, dressmakers, and various skivvies. Naturally she carries all her favorite pieces of furniture, her linens, her clothing, her jewels, her money chests, the instruments and apparatuses of her peculiar religious worship, fabrics for new robes, fans and feathers, mattresses, pillows, bolsters, carpets and curtains and screens, her cosmetics, and her own supply of spices, essences, balms, resins, incenses and perfumes. Not to forget her books, her mirrors, her astronomical tools and her own private Chaldaean soothsayer.

Her retinue is said to number well over a thousand, so of course they don’t fit into the palace. Caesar has built them a village on the periphery of Transtiberim, and the Transtiberini are livid. It is war to the death between the natives and the interlopers, so much so that Caesar has issued an edict promising that all Transtiberini who raise a knife to slice the nostrils or ears of a detested foreigner will be transported to one of his new colonies whether they like it or not.

I have met the woman—incredibly haughty and arrogant. She threw a reception for us Roman peasants with Caesar’s official blessing, had some sumptuous barges pick us up near the Pons Aemilius and then, upon disembarking, we were ferried in litters and sedan chairs spewing cushions and fur rugs. She held court—an exact description—in the huge atrium, and invited us to make free of the loggia as well. She’s a pathetic dab of a thing, comes up to my navel, and I am not a tall man. A beak of a nose, but the most extraordinary eyes. The Great Man, who is infatuated, calls them lion’s eyes. It shamed me to witness his conduct with her—he’s like a boy with his first prostitute.

Manius Lepidus and I prowled around a little and found the temple. My dear Brutus, we were aghast! No less than twelve statues of these things—the bodies of men or women, but the heads of beasts—hawk, jackal, crocodile, lion, cow, et cetera. The worst was female, had a grossly swollen belly and great pendulous breasts, all crowned with a hippopotamus’s head—absolutely revolting! Then the high priest came in—he spoke excellent Greek—and offered to tell us who was who—better to say, which was which—in that bizarre and off-putting pantheon. He was shaven-headed, wore a pleated white linen dress, and a collar of gold and gems around his neck that must be worth as much as my whole house.

The Queen was dolled up in cloth-of-gold from head to foot—her jewels could buy you Rome. Then Caesar came out of some inner sanctum carrying his child. Not at all shy! Smiled at us as if we were new subjects, greeted us in Latin. I must say that he looks very like Caesar. Oh yes, it was a royal occasion, and I begin to suspect that the Queen is working on Caesar with a view to making him the King of Rome. Dear Brutus, our beloved Republic grows ever farther away, and this landslide of new legislation will end in stripping the First Class of all its old entitlements.

On a different note, Marcus Antonius has married Fulvia—now there’s a woman I really loathe! I dare-say you have heard that Caesar said in the House that Antonius had tried to murder him. Much as I deplore Caesar and all he stands for, I am glad that Antonius didn’t succeed. If Antonius were the dictator, things would be much worse.

More interesting still is the marriage between Caesar’s great-niece Octavia and Gaius Claudius Marcellus Minor. Yes, you read aright! He’s done very well for himself, while his brother and first cousin sit in exile, their property gone—Marcellus Minor’s way, I add. There has been one extremely fascinating consequence of this alliance that almost made me wish I could bend my principles and attend the Senate. It happened during a meeting of the Senate Caesar convoked to discuss his first group of agrarian laws. As the senators dispersed afterward, Marcellus Minor asked Caesar to pardon his brother, Marcus, who is still on Lesbos. When Caesar said no several times, would you believe that Marcellus Minor fell to his knees and begged? With that repellent man Lucius Piso adding his voice, though he didn’t fall to his knees. They say that Caesar looked utterly taken aback, quite horrified. Retreated until he collided with Pompeius Magnus’s statue, roaring at Marcellus Minor to get up and stop making a fool of himself. The upshot was that Marcus Marcellus is now pardoned. Marcellus Minor is going around saying that he intends to return all brother Marcus’s estates to him. He won’t be able to do the same for cousin Gaius Marcellus, as I hear he has expired of some creeping disease. Brother Marcus will come home after visiting Athens, we are told by Marcellus Minor.

Of course I am not enamored of any of the Claudian Marcelli, as you know. Whatever caused them to renounce their patrician status and join the Plebs is too far in the past to be known, but the fact that they did that does say something about them, doesn’t it?

I will write again when I have more news.

After Caesar explained Rome’s aversion to kings and queens and the religious significance in crossing the pomerium, the Queen of Egypt’s natural indignation at not being able to go inside the city faded. Every place had its taboos, and Rome’s were all tied to the notion of the Republic, to an abhorrence of absolute rule that verged on the fanatical—and could—and did—breed fanatics like Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis, whose appalling suicide was still the talk of Rome.

To Cleopatra, absolute rule was a fact of life, but if she couldn’t enter the city, then she couldn’t enter the city. When she wept at the thought that she wouldn’t see Caesar triumph, he told her that a knight friend of his banker Oppius’s, one Sextus Perquitienus, had offered to let her share his loggia with him. As his house was built on the back cliff of the Capitol overlooking the Campus Martius, Cleopatra would be able to see the start of the parade, and follow it until it turned the corner of the Capitol back cliff to enter the city through the Porta Triumphalis, a special gate opened solely for triumphs.

The veteran legionaries from the Gallic campaign were to march in this first triumph, which actually meant a mere five thousand men; only a few in each of the legions numbered during Gallic War times were still under the Eagles, as Rome still did not maintain a long-serving regular army. Though the eldest of the Gallic War veterans was but thirty-one years old if he had enlisted at seventeen, the natural attrition of war weariness, wounds and retirement had taken a huge toll.

But when the order of march was issued, the Tenth found to its dismay that it would not be in the lead. The Sixth had been given that honor. Having mutinied three times, the Tenth had fallen from Caesar’s favor, and would go last.

The original eleven legions numbered between the Fifth Alauda and the Fifteenth contributed these five thousand veterans, kitted in new tunics, with new horsehair plumes in their helmets, and carrying staves wreathed in laurels—actual weapons were not allowed. The standard-bearers wore silver armor, and the Aquilifers, who carried each legion’s silver Eagle, wore lion skins over their silver armor. No compensation to the unhappy Tenth, which decided to take a peculiar revenge.

This was one triumph that the consuls of the year could participate in, as the triumphator, whose imperium had to outweigh all others, was Dictator. Therefore Lepidus sat with the other curule magistrates upon the podium of Castor’s in the Forum. The rest of the Senate led the parade; most of them were Caesar’s new appointees, so the senators at around five hundred made an imposing body of marchers—too few in purple-bordered togas, alas.

Behind the Senate came the tubilustra, a hundred-strong band of men blowing the gold horse-headed trumpets an earlier Ahenobarbus had brought back from his campaign in Gaul against the Arverni. Then came the carts carrying the spoils, interspersed with large flat-topped drays that served as floats to display incidents from the campaign played by actors in the correct costumes and surrounded by the right props. The staff of Caesar’s bankers, who had had the gigantic task of organizing this staggering spectacle, had been driven almost to the point of madness trying to find sufficient actors who looked like Caesar, for he featured prominently in most of the float enactments, and everyone in Rome knew him.

All the famous scenes were there: a model of the siege terrace at Avaricum; an oaken Veneti ship with leather sails and chain shrouds; Caesar at Alesia going to the rescue of the camp where the Gauls had broken in; a map of the double circumvallation at Alesia; Vercingetorix sitting cross-legged on the ground as he submitted to Caesar; a model of the mesa top and its fortress at Alesia; floats crowded with outlandish long-haired Gauls, said long hair stiffened into grotesque styles with limey clay, their tartans bright and bold, their longswords (of silvered wood) held aloft; a whole squadron of Remi cavalry in their brilliant outfits; the famous siege of Quintus Cicero and the Seventh against the full might of the Nervii; a depiction of a Britannic stronghold; a Britannic war chariot complete with driver, spearman and pair of little horses; and twenty more pageants. Every cart or float was drawn by a team of oxen garlanded with flowers, trapped in scarlet, bright green, bright blue, yellow.

Intermingled with all these fabulous displays, groups of whores danced in flame-colored togas, accompanied by capering dwarves wearing the patchwork coats of many colors called centunculi, musicians of every kind, men blowing gouts of fire from their mouths, magicians and freaks. No gold crowns or wreaths were exhibited, as the Gauls had tendered none to Caesar, but the carts of spoils glittered with gold treasures. Caesar had found the accumulated hoard of the Germanic Cimbri and Teutones at Atuatuca, and had also plundered centuries of precious votives held by the Druids at Carnutum.

Next came the sacrificial victims, two pure white oxen to be offered to Jupiter Optimus Maximus when the triumphator reached the foot of the steps to his temple on the Capitol. A destination some three miles away, for the procession wended a path through the Velabrum and the Forum Boarium, then into the Circus Maximus, went once right around it, up it again and out its Capena end to the Via Triumphalis, and finally down the full length of the Forum Romanum to the foot of the Capitoline mount, where it stopped.

Here those prisoners of war doomed to die were taken to be strangled in the Tullianum; here the floats and lay participants disbanded; here the gold was put back into the Treasury; and here the legions turned into the Vicus Iugarius to march back to the Campus Martius through the Velabrum, there to feast and wait until their money was distributed by the legion paymasters. It was only the Senate, the priests, the sacrificial animals and the triumphator who continued up the Clivus Capitolinus to Jupiter Optimus Maximus, escorted now by special musicians who blew the tibicen, a flute made from the shinbone of a slain enemy.

The two white oxen were smothered in garlands and ropes of flowers and had gilded horns and hooves; they were shepherded, already drugged, by the popa, the cultarius, and their acolytes, who would expertly perform the killing.

After them came the College of Pontifices and the College of Augurs in their particolored togas of scarlet and purple stripes, each augur bearing his lituus, a curliqued staff that distinguished him from the pontifices. The other, minor sacerdotal colleges in their specific robes followed, the flamen Martialis looking very strange in his heavy circular cape, wooden clogs, and ivory apex helmet. At Caesar’s triumphs there would be no flamen Quirinalis, as Lucius Caesar marched as Chief Augur instead of his other role; and also no flamen Dialis, for that special priest of Jupiter was actually Caesar, long since released from his duties.

The next section of the parade was always very popular with the crowd, as it consisted of the prisoners. Each was clad in his or her very best regalia, gold and jewels, looking the picture of health and prosperity; it was no part of the Roman triumph to display prisoners ill-treated or beaten down. For this reason, they were kept hostage in some rich man’s house while they waited for their captor to triumph. Rome of the Republic did not imprison.

King Vercingetorix came first; only he, Cotus and Lucterius were to die. Vercassivellaunus, Eporedorix and Biturgo—and all the other, more minor prisoners of war—would be sent back to their peoples unharmed. Once, many years earlier, Vercingetorix had wondered at the prophecy which said he would wait six years between his capture and his death; now he knew. Thanks to civil war and other things, it had taken Caesar six years to achieve his triumph over Long-haired Gaul.

The Senate had decreed a very special privilege for Caesar: he was to be preceded by seventy-two rather than the Dictator’s usual twenty-four lictors. Special dancers and singers were to weave their way between the lictors, hymning Caesar Triumphator.

So by the time that Caesar’s turn to move actually came, the procession had already been under way for two long summer hours. He rode in the triumphal chariot, a four-wheeled, extremely ancient vehicle more akin to the ceremonial car of the King of Armenia than to the two-wheeled war chariot; his was drawn by four matched grey horses with white manes and tails, Caesar’s choice. Caesar wore triumphal regalia. This consisted of a tunic embroidered all over in palm leaves and a purple toga lavishly embroidered in gold. On his head he wore the laurel crown, in his right hand he carried a laurel branch, and in his left the special twisted ivory scepter of the triumphator, surmounted by a gold eagle. His driver wore a purple tunic, and at the back of the roomy car stood a man in a purple tunic who held a gilded oak-leaf crown over Caesar’s head, and occasionally intoned the warning given to all triumphators:

“Respice post te, hominem te memento!”*

Though Pompey the Great had been too vain to subscribe to the old custom, Caesar did. He painted his face and hands with bright red minim, an echo of the terra-cotta face and hands possessed by the statue of Jupiter Optimus Maximus in his temple. The triumph was as close to emulating a god as any Roman ever came.

Right behind the triumphal car walked Caesar’s war horse, the famous Toes with the toes (actually the current one of several such over the years—Caesar bred them from the original Toes, a gift from Sulla), the General’s scarlet paludamentum draped across him. To Caesar it would have been unthinkable to triumph without giving Toes, the symbol of his fabled luck, his own little triumph.

After Toes came the throng of men who considered that Caesar’s Gallic campaign had liberated them from enslavement; they all wore the cap of liberty on their heads, a conical affair that denoted the freed man.

Next, those of his Gallic War legates in Rome at this time, all in dress armor and mounted on their Public Horses.

And, in last place, the army, five thousand men from eleven legions who shouted “Io triumphe!” as they marched. The bawdy songs would come later, when there were more ears to hear them and chuckle.

When Caesar stepped into the triumphal car its left front wheel came off, pitching him forward on to the front wall, sending the triumphal intonator toppling, and setting the horses to nervous whinnying and rearing.

A collective gasp went up from all those who saw it happen.

“What is it? Why are people so shocked?” Cleopatra asked of Sextus Perquitienus, who had gone chalk white.

“A frightful omen!” he whispered, holding up his hand in the sign to ward off the Evil Eye.

Cleopatra followed suit.

The delay was minimal; as if by magic, a new wheel appeared and was fitted swiftly. Caesar stood to one side, his lips moving. Though Cleopatra could not know it, he was reciting a spell.

Lucius Caesar, Chief Augur, had come running.

“No, no,” Caesar said to him, smiling now. “I will expiate the omen by climbing the steps of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on my knees, Lucius.”

“Edepol, Gaius, you can’t! There are fifty of them!”

“I can, and I will.” He pointed to a flagon strapped to the car wall on its inside. “I have a magic potion to drink.”

Off went the triumphal chariot, and soon the army was marching to bring up the parade’s rear, two miles behind the Senate.

In the Forum Boarium the triumphator had to stop and salute the statue of Hercules, always naked save on a triumphal day, when he too was clad in triumphal regalia.

A hundred and fifty thousand people were jammed into the long bleachers of the Circus Maximus; the roars and cheers which went up when Caesar entered could be heard by Cleopatra’s servants in her palace. But by the time that the car had made its way up one side of the spina, around its Capena end, down the other side, then up again toward the Capena exit, the army was all inside, and the crowd was worn out by cheering. So when the Tenth began to sing its new marching song, everyone quietened to listen.

“Make way for him, seller of whores

Take note of his fine head of hair

His other head bangs cunty doors

He fucks ’em all, in bed or chair

In Bithynia he sold his arse

His admiral was short some fleets

So Caesar shit a fleet of class

Between the kingly linen sheets

He’s never lost a single battle

Though his tally’s about fifty

He rounds ’em up like mooing cattle

Our King of Rome neat and nifty!”

Caesar called to Fabius and Cornelius, tailing the seventy-two lictors ahead of him.

“Go tell the Tenth that if they don’t stop singing that song, I’ll strip them of their share of the booty and discharge them minus their land!” he snapped.

The message was conveyed and the ditty promptly ceased, but many were the debates in the College of Lictors as to which of the verses gave Caesar the most offense; the conclusion Fabius and Cornelius reached was that the reference to selling his arse had gotten under Caesar’s skin, but a few of the other lictors were in favor of the “King of Rome” phrase. Certainly it wasn’t the bawdiness of the Tenth’s song; that was standard practice.

* * *

By the time the long business had ended, night was falling. Division of the spoils would have to wait until the morrow. The Field of Mars turned into a camp, for all the retired veterans were there too, having watched the triumph from the crowds. Aman’s share had to be collected in person unless, as happened in the case of Caesar’s triumph, many of the veterans lived in Italian Gaul. Groups of them had clubbed together and armed one representative with an authorizing document, which would contribute to the difficulties the legion pay-masters inevitably suffered.

The rankers each received 20,000 sesterces (more than the pay for twenty years of service); junior centurions received upward of 40,000 sesterces, and the top centurions 120,000 sesterces. Huge bonuses, more than any army’s in history, even the army of Pompey the Great after he conquered the East and doubled the entire contents of the Treasury. Despite this bounty, the soldiers of all ranks went away angry. Why? Because Caesar had set aside a small percentage and given it to the free poor of Rome, who each received 400 sesterces, 36 pounds of oil, and 15 modii of wheat. What had the free poor done to deserve a share? Though the free poor were ecstatic, the army was anything but.

The general military consensus was that Caesar was up to something, but what? After all, there was nothing to stop a free poor man from enlisting in the legions, so why was Caesar gifting men who hadn’t?

The triumphs for Egypt, Asia Minor and Africa followed in quick succession, none as spectacular as Gaul, but nonetheless above the standard of nine out of ten triumphs. The Asia triumph contained a float of Caesar at Zela surrounded by all his crowns: above the scene was a large, beautifully lettered placard that read VENI, VIDI, VICI. Africa was last, and the least approved of by Rome’s elite, for Caesar let his anger destroy his common sense and used the floats to deride the Republican high command. There was Metallus Scipio indulging in pornography, Labienus mutilating Roman troops, and Cato guzzling wine.

The triumphs were not the end of the extra entertainments that year. Caesar also gave magnificent funeral games for his daughter, Julia, who had been very much loved by the ordinary Roman people; she had grown up in the Subura, surrounded by the ordinary people, and never held herself above them. Which was why they had burned her in the Forum Romanum, and why her ashes lay in a magnificent tomb on the Campus Martius—unheard of.

There were plays in Pompey’s stone theater and in temporary wooden ones erected wherever there was space enough; the comedies of Plautus, Ennius and Terence were popular, but everyone liked the simple Atellan mime best. This was a farce stuffed with ludicrous stock characters and played minus masks. However, all tastes had to be catered for, so one small venue was reserved for highbrow drama by Sophocles, Aeschylus and Euripides.

Caesar also instituted a competition for new plays, and offered a generous prize for the best effort.

“You really ought to write plays as well as histories, my dear Sallustius,” he said to Sallust, whom he liked very much. As well for Sallust that he did; Sallust had been recalled from his governorship of Africa Province after he plundered the place unashamedly. The matter had been hushed up when Caesar personally paid out millions in compensation to aggrieved grain and business plutocrats; yet here was Caesar, still liking Sallust.

“No, I’m not a playwright,” said Sallust, shaking his head in revulsion at the mere thought. “I’m too busy writing a very accurate history of Catilina’s conspiracy.”

Caesar blinked. “Ye gods, Sallustius! Then I hope that you’re lauding Cicero to the skies.”

“Anything but,” said the unrepentant looter of his province cheerfully. “I blame the whole affair on Cicero. He manufactured a crisis to distinguish his consulship above banality.”

“Rome might become as hot as Utica when you publish.”

“Publish? Oh no, I daren’t publish, Caesar.” He giggled. “At least, not until after Cicero’s dead. I hope I don’t have to wait twenty years!”

“No wonder Milo horsewhipped you for philandering with his darling Fausta,” said Caesar, laughing. “You’re incorrigible.”

Plays were not the entirety of Julia’s funeral games. Caesar tented in the whole of the Forum Romanum and his own Forum Julium and gave gladiatorial games, wild-beast shows, combats between condemned prisoners of war, and exhibitions of the latest martial craze, fencing with long, whippy swords useless in a battle.

After which he gave a public banquet for all of Rome on no less than 22,000 tables. Among the delicacies were 6,000 fresh water eels he had to borrow from his friend Lucilius Hirrus, who refused to sell them; his price was replacement. The wines flowed like water, the tables groaned with food, and there was enough left over to enable the poor to heft home sacks of goodies to augment their menu for some time to come.

* * *

Cicero was still writing to Brutus in Italian Gaul.

I know I’ve already told you about Caesar’s disgraceful lampooning of the Republican heroes in Africa, but I am still fulminating about it. How can the man have such excellent taste when it comes to things like games and shows, yet make a mockery out of worthy Roman opponents?

However, that is not why I write. I have divorced that termagant Terentia at last—thirty years of misery! So I am now an eligible sixty-year-old bachelor, a very strange and freeing sensation. So far I have been offered two widows, one the sister of Pompeius Magnus, the other his daughter. You do know that Publius Sulla died very suddenly? It upset the Great Man, who always liked him—why escapes me. Anyone whose father was adopted by a man like Sextus Perquitienus Senior and was brought up in that household cannot help but be a cur. So his Pompeia is a widow. However, I prefer the other Pompeia—for one thing, she’s thirty years younger. For another, she seems to be a fairly sanguine widow, isn’t mourning Faustus Sulla overmuch. That’s probably because the Great Man permitted her to keep all her property, which is vast. I shall not marry a poor woman, my dear Brutus, but nor, after Terentia, will I marry a woman who is in complete control of her own fortune. So perhaps neither Pompeia Magna is a good choice. We Romans allow women too much autonomy.

There has been another divorce in the ranks of the Tullii Cicerones. My darling Tullia has finally severed her union to that rabid boar Dolabella. I requested that her dowry payments be returned, as I am entitled to when the wife is the injured party. To my surprise, Dolabella said yes! I think he’s trying to get back into favor with Caesar, hence the promised repayment. Caesar is a stickler for women being treated properly, witness his concern for Antonia Hybrida. Then what happens? Tullia informs me that she is with child by Dolabella! Oh, what is the matter with women? Not only that, but Tullia is so terribly downcast, doesn’t seem to be interested in the coming baby, and has the temerity to blame me for the divorce! Says I nagged her into it. I give up.

No doubt Gaius Cassius has written to tell you that he is coming home from Asia Province. I rather gather that he and Vatia Isauricus have nothing in common save their wives, your sisters. Well, Vatia hewed to Caesar and cannot be pried loose. From what Cassius tells me in his letter, Vatia is a very strict governor, has regulated the taxes and tithes of Asia Province (not due to be enforced for several more years) to make it impossible for a publicanus or any other sort of Roman businessman to make one sestertius of profit from the Amanus to the Propontis. I ask you, Brutus, what does Rome have provinces for, if not to let Romans make a sestertius or two out of them? Truly, I think Caesar believes Rome should pay her provinces, not the other way around!

Gaius Trebonius has arrived in Rome—driven out of Further Spain by Labienus and the two Pompeii, it seems. He was struggling after Quintus Cassius’s deplorable conduct when he was governor—a regular Gaius Verres, they say. The three Republicans landed to hysterical joy, and have been raising legions with marked success. Having moored his many ships in Balearic waters, Gnaeus Pompeius is now living in Corduba as the new Roman governor. Labienus is the commander of military matters.

I wonder what Caesar plans to do?

“I think Caesar will be going to Spain as soon as his present legislation is done with,” said Calpurnia to Marcia and Porcia.

Porcia’s eyes lit into a blaze, her face suffused with hope. “This time it will be different!” she cried, smacking her right fist into her left palm jubilantly. “Every day that passes sees Caesar’s legions more disaffected, and since the time of Quintus Sertorius, the Spanish have produced legionaries every bit as good as those Italy produces. You wait and see, Spain will be the end of Caesar. I pray for it!”

“Come, Porcia,” Marcia said, her eyes meeting Calpurnia’s ruefully, “remember our company.”

“Oh, really!” Porcia snapped, her hand going out to clench Calpurnia’s. “Why should poor Calpurnia care? Caesar spends all his time across the Tiber with That Woman!”

Very true, thought Calpurnia. The only nights he occupies his Domus Publica bed are those before a meeting of the Senate at dawn. Otherwise, he’s there with her. I’m jealous and I hate feeling jealous. I hate her too, but I still love Caesar.

“I believe,” she said with composure, “that the Queen is extremely knowledgeable about government, and that very little of his time with her is devoted to love. From what he says, they talk of his laws. And political matters.”

“You mean he has the gall to mention her name to his wife?” Porcia demanded incredulously.

“Yes, often. That’s why I don’t worry very much about her. Caesar doesn’t act one scrap differently toward me than he ever has. I am his wife. At best, she’s his mistress. Though,” said Calpurnia wistfully, “I would love to see the little boy.”

“My father says he’s a beautiful child,” Marcia offered, then frowned. “The interesting thing is that Atia’s boy, Octavius, detests the Queen and refuses to believe that the child is Caesar’s. Though my father says the child undoubtedly is Caesar’s, he’s very like him. Octavius calls her the Queen of Beasts because of her gods, which apparently have the heads of beasts.”

“Octavius is jealous of her,” said Porcia.

Calpurnia’s eyes widened. “Jealous? But why?”

“I don’t know, but my Lucius knows him from the drills on the Campus Martius, and says he makes no secret of it.”

“I didn’t know Octavius and Lucius Bibulus were friends,” said Marcia.

“They’re the same age, seventeen, and Lucius is one of the few who doesn’t sneer at Octavius when he goes to the drills.”

“Why should anyone sneer?” asked Calpurnia, puzzled.

“Because he wheezes. My father,” Porcia went on, transfigured at the mere mention of Cato, “would say that Octavius ought not to be punished for an infliction of the gods. My Lucius agrees.”

“Poor lad. I didn’t know,” said Calpurnia.

“Living in that house, I do,” Marcia said grimly. “There are times when Atia despairs for his life.”

“I still don’t understand why he should be jealous of Queen Cleopatra,” Calpurnia said.

“Because she’s stolen Caesar,” Marcia contributed. “Caesar was spending considerable time with Octavius until the Queen came to Rome. Now, he’s forgotten Octavius exists.”

“My father,” Porcia brayed, “condemns jealousy. He says that it destroys inner peace.”

“I don’t think we’re terribly jealous, yet none of us enjoys inner peace,” said Marcia.

Calpurnia picked up a kitten wandering around the floor and kissed its sleek, domed little skull. “I have a feeling,” she said, cheek against its fat tummy, “that Queen Cleopatra is not at peace either.”

A shrewd guess; having learned that Caesar was going to Spain to deal with the Republican rebellion there, Cleopatra was filled with a rather royal dismay.

“But I can’t live in Rome without you!” she said. “I refuse to let you leave me here alone!”

“I’d say, go home, except that autumnal and winter seas are perilous between here and Alexandria,” Caesar said, keeping his temper. “Stick it out, my love. The campaign won’t be long.”

“I heard that the Republicans have thirteen legions.”

“I imagine at least that many.”

“And you’ve discharged all but two of your veteran legions.”

“The Fifth Alauda and the Tenth. But Rabirius Postumus, who has consented to act as my praefectus fabrum again, is recruiting in Italian Gaul, and a lot of the discharged veterans there are bored enough to re-enlist. I’ll have eight legions, sufficient to beat Labienus,” Caesar said, and leaned to kiss her with lingering enjoyment. She’s still miffed. Change the subject. “Have you looked at the census data?” he asked.

“I have, and they’re brilliant,” she said warmly, diverted. “When I return to Egypt, I shall institute a similar kind of census. What fascinates me is how you managed to school thousands of men to take it door-to-door.”

“Oh, men love to ask nosy questions. The training lies more in teaching them how to deal with people who resent nosy questions.”

“Your genius staggers me, Caesar. You do everything so efficiently, yet so swiftly. The rest of us toil in your wake.”

“Keep paying me compliments, and my head won’t fit through your door,” he said lightly, then scowled. “At least yours smack of sincerity! Do you know what those idiots put on that wretched gold quadriga they erected in Jupiter Optimus Maximus’s porticus?”

She did know. While she approved of it and agreed with it, she knew Caesar well enough by now to understand why it had so angered him. The Senate and the Eighteen had commissioned a gold sculpture of Caesar in a four-horse chariot atop a globe of the world, another of the honors they heaped upon him against his will.

“I am on the horns of a dilemma about these honors,” he had said to her some time ago. “When I refuse them, I’m apostrophized as churlish and ungrateful, yet when I accept them, I’m apostrophized as regal and arrogant. I told them I refused to condone this awful construction, but they’ve gone ahead with it anyway.”

He hadn’t seen the “awful construction” until this morning, when it was unveiled. The sculptor, Arcesilaus, had done well; his four horses were superb. Pleasantly surprised, Caesar had toured around it with equanimity until he noticed the plaque affixed to the front wall of the chariot. It said, in Greek, exactly what the statue of him in the Ephesus agora said—GOD MADE MANIFEST and all the rest.

“Take that abomination off!” he snapped.

No one moved to obey.

One of the senators was wearing a dagger on his belt; Caesar snatched it and used it to dig into the chased gold surface until the plaque came off. “Never, never say such things about me!” he said, and walked out, so furious that the plaque, thrown away, was crushed and crumpled into a ball of metal.

So now Cleopatra said pacifically, “Yes, I know about it. And I am sorry it offended you.”

“I do not want to be the King of Rome, and I do not want to be a god!” he snarled.

“You are a God,” she said simply.

“No, I am not! I am a mortal man, and I will suffer the fate of all mortal men, Cleopatra! I—will—die! Hear that? Die! Gods don’t die. If I were to be made a god after my death, that would be different—I’d be sleeping the eternal sleep, and not know I was a god. But while I am mortal, I cannot be a god. And why,” he demanded, “do I need to be King of Rome? As Dictator, I can do whatever has to be done.”

“He’s like a bull being tormented by a crowd of little boys safely on the other side of the stall railings,” said Servilia to Gaius Cassius with great satisfaction. “Oh, I am enjoying it! So is Pontius Aquila.”

“How is your devoted lover?” Cassius asked sweetly.

“Working for me against Caesar, but very subtly. Of course Caesar doesn’t like him, but fair-mindedness is one of Caesar’s weaknesses, so if a man shows promise, he’s advanced, even if he is a pardoned Republican—and Servilia’s lover,” she purred.

“You’re such a bitch.”

“And I always was a bitch. I had to be, to survive Uncle Drusus’s household. You know Drusus confined me to the nursery and forbade me to leave the premises until I married Brutus’s tata, don’t you?” she asked.

“No, I didn’t. Why would a Livius Drusus do that?”

“Because I spied for my father, who was Drusus’s enemy.”

“At what age?”

“Nine, ten, eleven.”

“But why were you living with your mother’s brother instead of your own father?” Cassius asked.

“My mother committed adultery with Cato’s father,” she said, her face twisting hideously even at so old a memory, “and my father chose to deem all his own children by her as someone else’s.”

“That would do it,” said Cassius clinically. “Yet you spied for him?”

“He was a patrician Servilius Caepio,” she said, as if that explained it all.

Knowing her, Cassius supposed it did.

“What happened with Vatia in Africa Province?” she asked.

“He wouldn’t let me collect my or Brutus’s debts.”

“Oh, I see.”

“How is Brutus?”

Her black brows rose, she looked indifferent. “How would I know? He doesn’t write to me any more than he writes to you. He and Cicero dribble words to each other. Well, why not? Both of them are old women.”

Cassius grinned. “I saw Cicero in Tusculum on my way, stayed with him overnight. He’s very busy writing a paean to Cato, if you like that idea. No, I thought you wouldn’t. However, the war looming in the Spains had him twittering and fluttering, which surprised me, given his detestation for Caesar. I asked him why, and he said that if the Pompeius boys beat Caesar, he thought they would be far worse masters for Rome than Caesar is.”

“And what did you reply to that, Cassius dear?”

“That, like him, I’d settle for the easygoing old master I know. The Pompeii hail from Picenum, and I’ve never known a Picentine who wasn’t cruel to the marrow. Scratch a Picentine, and you reveal a barbarian.”

“That’s why Picentines make such wonderful tribunes of the plebs. They love to strike when the back is turned, and they’re never happier than when they can make mischief. Pah!” Servilia spat. “At least Caesar is a Roman of the Romans.”

“So much so that he has the blood to be King of Rome.”

“Just like Sulla,” she agreed. “However—and also like Sulla!—he doesn’t want to be the King of Rome.”

“If you can say that so positively, then why are you and certain others trying very hard to make it seem as if Caesar itches to tie on the diadem?”

“It passes the time,” Servilia said. “Besides, I must have a tiny bit of Picentine in me. I adore making mischief.”

“Have you met her majesty?” Cassius asked, feeling his own Romanness expand. Oh, it was good to be home! Tertulla might be half Caesar’s, but the other half was pure Servilia, and both halves made for a fascinatingly seductive wife.

“My dear, her majesty and I are bosom friends,” Servilia cooed. “What fools Roman women can be! Would you believe that most of my female peers have decided to label the Queen of Egypt infra dignitatem? Silly of them, isn’t it?”

“Why don’t you find her beneath your dignity?”

“It’s more interesting to stand on good terms with her. As soon as Caesar leaves for Spain, I shall bring her into fashion.”

Cassius frowned. “I’m sure your motives aren’t admirable, Mama-in-law, but whatever they are, they elude me. You know so little about her. She might be a wilier snake than you.”

Servilia lifted her arms above her head and stretched. “Oh, but there you’re quite wrong, Cassius. I know a great deal about Cleopatra. You see, her younger sister spent almost two years here in Rome—Caesar exhibited her as his captive in his Egyptian triumph. She was put to live with old Caecilia, and as Caecilia is a good friend of mine, I came to know Princess Arsinoë well. We chatted for hours about Cleopatra.”

“That triumph’s almost three months into the past. Where’s Princess Arsinoë now?” Cassius peered about theatrically. “I’m surprised she isn’t living here with you.”

“She would be, had I had half a chance. Unfortunately Caesar put her on a ship bound for Ephesus the day after his triumph. I hear she’s to serve Artemis in the temple there. The moment she escapes, she can be killed for a nice reward. Apparently he gave Cleopatra his word that he’d clip Arsinoë’s wings. Such a pity! I was so looking forward to reuniting the two sisters.”

He shivered. “There are times, Servilia, when I am profoundly glad that you like me.”

In answer, she changed the subject. “Do you really prefer Caesar as your master, Cassius?”

His face darkened. “I would prefer to have no master. To acknowledge a master is an offense against Quirinus,” he snarled.

*“Look behind thee, remember that thou art a mortal man!”